Aristides de Sousa Mendes

Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches (Portuguese pronunciation: [ɐɾiʃˈtiðɨʒ ðɨ ˈsowzɐ ˈmẽdɨʃ]) GCC, OL (July 19, 1885 – April 3, 1954) was a Portuguese consul during World War II.

Aristides de Sousa Mendes | |

|---|---|

Aristides in his 20s | |

| Born | Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches July 19, 1885 Cabanas de Viriato, Viseu, Portugal |

| Died | April 3, 1954 (aged 68) Lisbon, Portugal |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Alma mater | University of Coimbra |

| Occupation | Consul |

| Known for | Saving the lives of thousands of refugees seeking to escape the Nazi terror during World War II |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Angelina Coelho de Sousa Mendes

(m. 1908; died 1948)Andrée Cibial de Sousa Mendes

(m. 1949; |

| Children | [With Marie Angelina Coelho]

Aristides César, Manuel Silvério, José António, Clotilde Augusta, Isabel Maria, Feliciano Artur Geraldo, Elisa Joana, Pedro Nuno, Carlos Francisco Fernando, Sebastião Miguel Duarte, Teresinha Menino Jesus, Luís Felipe, João Paulo, Raquel Herminia [With Andrée Cibial] Marie-Rose |

| Parents |

|

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

|

|

| By country |

|

As the Portuguese consul-general in the French city of Bordeaux, he defied the orders of António de Oliveira Salazar's Estado Novo regime, issuing visas and passports to an undetermined number of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, including Jews. For this, Sousa Mendes was punished by the Salazar regime with one year of inactivity with the right to one half of his rank's pay, being obliged subsequently to be retired. However, he ended up never being expelled from the foreign service nor forced to retire and he received a full consul salary until his death in 1954.[1][2][3][4][5] One of Sousa Mendes most sympathetic biographers, Rui Afonso, has reckoned that he continued to receive a salary at least three times that of a teacher.[1][2]

Sousa Mendes was vindicated in 1988, more than a decade after the Carnation Revolution, which toppled the Estado Novo.

The number of visas issued by Sousa Mendes is disputed. Yad Vashem historian Avraham Milgram thinks that it was probably Harry Ezratty who was the first to mention in an article published in 1964 that Sousa Mendes had saved 30,000 refugees, of which 10,000 were Jews, a number which has since been repeated automatically by journalists and academics. Milgram says that Ezratty, imprudently, took the total number of Jewish refugees who passed through Portugal and ascribed it to the work of Aristides de Sousa Mendes. According to Milgram “the discrepancy between the reality and the myth of the number of visas granted by Sousa Mendes is great”.[6] A similar opinion is shared by British historian Neill Lochery, by the Portuguese ambassador João Hall Themido, by the Portuguese Ambassador Carlos Fernandes and by the Portuguese historian José Hermano Saraiva. On the other hand, French writer, Eric Lebreton argued that “Milgram did not account for the visas that were delivered in Bayonne, Hendaye and Toulouse”.[7] In 2015, Olivia Mattis, musicologist and Board President of the Sousa Mendes Foundation in the United States, published the findings of the Sousa Mendes Foundation stating that "tens of thousands" of visa recipients is a figure in the correct order of magnitude.[8]

For his efforts to save Jewish refugees, Sousa Mendes was recognized by Israel as one of the Righteous Among the Nations,[9] the first diplomat to be so honoured, in 1966.

Portuguese diplomats such as Ambassador João Hall Themido and Ambassador Carlos Fernandes have argued that Sousa Mendes actions have been inflated and twisted in order to attack Salazar. Similar opinion was voiced by historian Tom Gallagher who argues that evidence that Sousa Mendes efforts were especially directed towards fleeing Jews is also speculative. British, Americans and Portuguese, often people with means, figured prominently as recipients of visas.[10] Gallagher thinks that the disproportionate attention given to Sousa Mendes suggests that wartime history is being used as a political weapon in contemporary Portugal.[11]

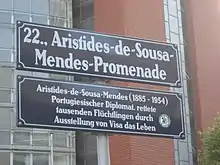

On 9 June 2020, Portugal granted official recognition to Sousa Mendes. Parliament decided a monument in the National Pantheon should bear his name.[12] In 2017 in the Portuguese border town of Vilar Formoso a memorial museum was opened, known as Vilar Formoso Fronteira da Paz (Frontier of Peace) recording the experiences of refugees entering Portugal, many of whom had been given visas by Sousa Mendes.[13]

Early life

Aristides de Sousa Mendes was born in Cabanas de Viriato, in Carregal do Sal, in the district of Viseu, Centro Region of Portugal, on July 19, 1885, shortly after midnight.[14] His twin brother César, born a few minutes earlier, had a July 18 birthday.[14] Their ancestry included a notable aristocratic line: their mother, Maria Angelina Ribeiro de Abranches de Abreu Castelo-Branco, was a maternal illegitimate granddaughter of the 2nd Viscount of Midões, a lower rural aristocracy title.[15] Their father, José de Sousa Mendes, was a judge on the Coimbra Court of Appeals.[16] César served as Foreign Minister in 1932, in the early days of António de Oliveira Salazar's regime.[17] Their younger brother, Jose Paulo, became a naval officer.[18]

Sousa Mendes and his twin studied law at the University of Coimbra, and each obtained his degree in 1908.[19] In that same year, Sousa Mendes married his childhood sweetheart, Maria Angelina Coelho de Sousa (born August 20, 1888).[20] They eventually had fourteen children, born in the various countries in which he served. Shortly after his marriage, Sousa Mendes began the consular officer career that would take him and his family around the world. Early in his career, he served in Demerara,[21] Zanzibar, Brazil, Spain, the United States, and Belgium.[22]

In August 1919, while posted in Brazil, he was "temporarily suspended by the Foreign Ministry, which regarded him as hostile to the republican regime."[23] Subsequently, "he had financial problems and was forced to take out a loan in order to provide for his family needs."[23] He returned home to Portugal where his son Pedro Nuno was born in Coimbra in April 1920.

In 1921, Sousa Mendes was assigned to the Portuguese consulate in San Francisco, and two more of his children were born there.[24]

In 1923, he angered some members of the Portuguese-American community because of his insistence that the Oakland's brotherhood of the Cult of the Holy Spirit should make a contribution to a Brazilian charity. Sousa Mendes decided to publish his arguments in local newspapers accusing the members of the brotherhood of lack of patriotism and disrespect for Portugal sparkling a dispute where both sides used the local press to attack each another. Sousa Mendes was instructed by the Foreign Office to stop insisting on something that was not part of his work as a consul and that the local Portuguese community was free to choose to which charities they wished to support. But Sousa Mendes ignored the orders and kept on publishing articles criticizing the members of the brotherhood and also banned the Portuguese notaries from performing any further services to the consulate. Ultimately, the conflict led to the US Department of State cancelling his consular exequatur and ask the Portuguese Government to replace Sousa Mendes as consul[25].[6][26][upper-alpha 1] While in San Francisco, Sousa Mendes helped establish a Portuguese Studies program at the University of California at Berkeley.[34]

In May 1926, a coup d'état replaced the republic in Portugal with a military dictatorship,[35] a regime that according to Sousa Mendes "had been greeted with delight" in Portugal.[35] He supported the new regime at first and his career prospects improved.[36] In March 1927, Sousa Mendes was assigned to serve as the Consul in Vigo in Spain, where he helped the military dictatorship neutralize political refugees.[36]

In 1929 he was sent to Antwerp, Belgium to serve as Dean of the Consular Corps.[37]

The year of 1934 was a tragic year for the Sousa Mendes family with the loss of two of their children: Raquel, barely one year old, and Manuel, who had just graduated from the University of Louvain.

In 1935 during the Brussels World Fair Sousa Mendes decided to publicly criticize the Portuguese Government for the low level of representation in the world fair. The Minister Armindo Monteiro considered this to be a serious lack of discipline and Sousa Mendes was again object of disciplinary proceedings that ended up with him being dismissed from the board of The House of Portugal in Antwerp. In that same year, Sousa Mendes was also investigated for tardiness in the transferring of consular funds to the Foreign Office in Lisbon and he had to ask the support of his brother César to provide him with the money needed to settle the lack of funds.[38] [39]

In 1938, he was assigned to the post of Consul-General of Bordeaux, France, with jurisdiction over the whole of the Southwest of France.[38]

World War II and Circular 14

In 1932, the Portuguese dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar began, and by 1933, the secret police, the Surveillance and State Defense Police, PVDE, had been created. According to historian Avraham Milgram, by 1938, Salazar "knew the Nazis' approach to the 'Jewish question'. From fears that aliens might undermine the regime, entry to Portugal was severely limited. Toward this end, the apparatus of the PVDE was extended with its International Department given greater control over border patrol and the entry of aliens. Presumably, most aliens wishing to enter Portugal at that time were Jews."[40] Portugal during World War II, like its European counterparts, adopted tighter immigration policies, preventing refugees from settling in the country. Circular 10, of 28 October 1938, addressed to consular representatives, deemed that settling was forbidden to Jews, allowing entrance only on a tourist visa for thirty days.[41]

On 9 November 1938, the Nazi government of Germany began open war against its Jewish citizens with the pogrom known as Kristallnacht, with over a thousand synagogues damaged or destroyed, thousands of Jewish businesses damaged, 30,000 Jews arrested and at least 91 Jews murdered. On 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, home at that time to the largest Jewish community in the world, precipitating the start of World War II. Salazar reacted by sending a telegram to the Portuguese Embassy in Berlin ordering that it should be made clear to the German Reich that Portuguese law did not allow any distinction based on race, and therefore Portuguese Jewish citizens could not be discriminated against.[42]

The German invasion of Poland led France and the United Kingdom to declare war on Germany. The number of refugees trying to make use of Portugal's neutrality as an escape route increased, and between the months of September and December approximately 9,000 refugees entered Portugal.[43] Passport forgery and false statements were common. The regime felt the need for tighter control. By 1939, the police had already dismantled several criminal networks responsible for passport forgery and several consuls had been expelled from service for falsifying passports.[44]

On 11 November 1939, the Portuguese government sent Circular 14 to all Portuguese consuls throughout Europe, stating the categories of war refugees whom the PVDE considered to be "inconvenient or dangerous."[45] The Dispatch allowed consuls to continue granting Portuguese transit visas, but established that in the case of "Foreigners of indefinite or contested nationality, the Stateless, Russian Citizens, Holders of a Nansen passport, or Jews expelled from their countries and those alleging to embark from a Portuguese port without a consular visa for their country of destination, or air or sea tickets, or an Embarkation Guarantee from the respective companies, the consuls needed to ask permission in advance of the Foreign Ministry head office in Lisbon."[46] With Europe at war, this meant that refugees fleeing from the Nazis would have serious difficulties.

Historian Neill Lochery asserts that Circular 14 "was not issued out of thin air" and that this type of barrier was not unique to Portugal and with the country's very limited economic resources it was viewed as necessary. It was economic reasons rather than ideological reasons that made the Portuguese avoid accepting more refugees says Lochery.[47] Milgram expressed similar views, asserting that Portugal's regime did not distinguish between Jews and non-Jews but rather between immigrant Jews who came and had the means to leave the country, and those lacking those means.[48] Portugal prevented Jews from putting down roots in the country not because they were Jews but because the regime feared foreign influence in general, and feared the entrance of Bolsheviks and left-wing agitators fleeing from Germany.[48] Milgram believes that antisemitic ideological patterns had no hold in the ruling structure of the "Estado Novo" and a fortiori in the various strata of Portuguese society.[49] Milgram also says that modern anti-Semitism failed "to establish even a toehold in Portugal"[50] while it grew racist and virulent elsewhere in early twentieth-century Europe. Salazar`s policies towards the Jews seem to have been favourable and consistent."[49] Nevertheless, although it was not anti-Semitism that motivated the Portuguese government, but the danger of mass emigration to the country,[51] the outcome of the border policy made life difficult for Jews fleeing Nazism.

Sousa Mendes' disobedience to the orders of the Salazar dictatorship

There are different views on the uniqueness of Sousa Mendes' actions: According to Dr. Mordecai Paldiel, past Director of the Department of the Righteous at Yad Vashem, "In Portugal of those days, it was unthinkable for a diplomatic official, especially in a sensitive post, to disobey clear-cut instructions and get away with it."[52] However, according to Yad Vashem historian Avraham Milgram "issuing visas in contravention of instructions was widespread at Portuguese consulates all over Europe" and that "this form of insubordination was rife in consular circles."[53] Sousa Mendes began disobeying Circular 14 almost immediately, on the grounds that it was an inhumane and racist directive.[54]

The process that ended with Sousa Mendes’ discharge from his consular career began with two visas issued during the Phoney War and long before the invasion of France: the first issued on 28 November 1939 to Professor Arnold Wiznitzer, an Austrian historian who had been stripped of his nationality by the Nuremberg Laws, and the second on 1 March 1940 to the Spanish Republican Eduardo Neira Laporte, an anti-Franco activist living in France. Sousa Mendes granted the visas first, and only after granting the visas did he ask for the required approvals.[55] Sousa Mendes was reprimanded and warned in writing that "any new transgression or violation on this issue will be considered disobedience and will entail a disciplinary procedure where it will not be possible to overlook that you have repeatedly committed acts which have entailed warnings and reprimands."[56]

When Sousa Mendes issued these visas, it was a deliberate act of disobedience to the decree of an authoritarian dictatorship. "Here was a unique act by a man who believed his religion imposed certain obligations", said Paldiel. "He said, 'I'm saving innocent lives,' as simply as he might have said, 'Come, walk with me in my garden.'"[57]

It is also by this time that Andrée Cibial, a French pianist and singer, disturbed Sousa Mendes' marriage. Andrée became his mistress and eventually got pregnant, which she publicly announced during a Sunday's mass at Riberac cathedral.[58]

On 10 May 1940, Germany launched a blitzkrieg offensive against France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, and millions of refugees took to the roads. On 15 May, Sousa Mendes issued transit visas to Maria Tavares, a Luxembourg citizen of Portuguese origin, and to her husband Paul Miny, also a Luxembourger.[59] Two weeks later, the couple returned to the Bordeaux Consulate asking Sousa Mendes to issue them false papers.[60] Sousa Mendes agreed to their request, and on 30 May 1940, he issued a Portuguese passport listing Paul Miny as Maria's brother, therefore as having Portuguese citizenship. This time Sousa Mendes risked himself a great deal more than he had before; disobeying Circular 14 was one thing, but issuing a passport with a false identity, for someone of military age was a crime.[61] Sousa Mendes later provided the following explanation: "This couple asked me for a Portuguese passport, where they would figure as brother and sister, for fear that the husband, who was still of military age, would be detained on passing the French border, and incorporated in the Luxembourg army then being organized in France."[62] Portuguese authorities were remarkably lax when dealing with this transgression. Paul Miny was a deserter (not a Jew) and Sousa Mendes' offence carried out a penalty of two year in prison and expulsion from public service.[63]

There were other cases from May 1940 where Sousa Mendes disobeyed Circular 14. Examples include issuing visas to the Ertag, Flaksbaum and Landesman families, all granted on 29 May, despite having been rejected in a telegram from the Portuguese dictator Salazar to Sousa Mendes.[64] Another example is the writer Gisèle Quittner, rejected by Salazar but rescued by Sousa Mendes, to whom she expressed her gratitude: "You are Portugal's best propaganda and an honor to your country. All those who know you praise your courage...."[65]

Encounter with Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Kruger

As the German army approached Paris, the largest single movement of refugees in Europe since the Early Middle Ages began. An estimated six to ten million people took to the roads and railways to escape the German invasion.[66] Bordeaux and other southern French cities were overrun by desperate refugees. One of these was a Chassidic Rabbi, Chaim Kruger, originally from Poland but more recently from Brussels, escaping with his wife and five children. Kruger and Sousa Mendes met by chance in Bordeaux, and quickly became friends.[67] Sousa Mendes offered a visa to the Kruger family in defiance of Circular 14. In response, Kruger took a moral stand and refused to accept the visa unless all of his "brothers and sisters" (the mass of Jewish refugees stranded on the streets of Bordeaux) received visas too. Kruger's response plunged Sousa Mendes into "a moral crisis of incalculable proportions."[68]

At the same time, Sousa Mendes was also living out a personal drama. Andrée Cibial, Sousa Mendes’ lover, pregnant with his child, showed up at the consulate and provoked a scandal in front of Sousa Mendes' family, getting herself imprisoned for the incident.[69] By this time, Sousa Mendes had a nervous breakdown and secluded himself in prayer, questioning whether or not he should issue as many visas as he could, saving lives at the expense of his own career.[70] "Here the situation is horrible and I am in bed because of a strong nervous breakdown,"[71] he wrote to his son-in-law on 13 June 1940.

Act of conscience

On 12 June, despite the guarantees given by Franco, personally, to the Portuguese Ambassador Teotónio Pereira, that even if Italy entered the war, Spain would remain neutral,[72][73] Spain took on the status of a non-belligerent power and invaded Tangiers, further endangering Portuguese neutrality.[72][73][upper-alpha 2] With German tanks approaching the Pyrenees and with anti-British demonstrations in Spain, demanding the return of Gibraltar, there was every prospect that Portugal and Spain would become embroiled in the hostilities.[72]

On June 12 Salazar issued instructions to the Portuguese consulates in France to provide the Infanta Marie Anne of Portugal, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg and Infanta Maria Antónia of Portugal Duchess of Parma with Portuguese Passports. With these Portuguese Passports the entire entourage of the royal families could get visas without creating problems to the neutrality of the Portuguese Government. This way Zita of Bourbon-Parma and her son Otto von Habsburg got their visas because they were descendants of Portuguese citizens. Following the German annexation of Austria, Otto was sentenced to death by the Nazi regime.[74]

On June 13, Salazar had to act fast again, these time to support the Belgium Royal family. Salazar sent instructions to the Portuguese Consulate in Bayonne saying the "Portuguese territory is completely open" to the Belgium Royal Family and its entourage.[75] [76]

On 16 June, despite his seclusion, Sousa Mendes issued 40 visas, including those for the Rothschild family, and he was paid his customary personal compensation fee for issuing visas on a Sunday.[77]

On 17 June, Pétain announced in a broadcast to the French people that "it is with a heavy heart that I tell you today that we must stop fighting," and he calls on the Germans for an armistice that will end the fighting. On that same day, Sousa Mendes emerged from his seclusion, impelled by "a divine power,"[78] with his decision made. According to his son Pedro Nuno,

My father got up, apparently recovering his serenity. He was full of punch. He washed, shaved and got dressed. Then he strode out of his bedroom, flung open the door to the chancellery, and announced in a loud voice: 'From now on I'm giving everyone visas. There will be no more nationalities, races or religions.' Then our father told us that he had heard a voice, that of his conscience or of God, which dictated to him what course of action he should take, and that everything was clear in his mind.[79]

His daughter Isabel and her husband Jules strongly opposed his decision, and tried to dissuade him from what they considered to be a fatal mistake.[80] But Sousa Mendes did not listen to them and instead began to work intensively to grant the visas. "I would rather stand with God and against man than with man and against God," he reportedly explained.[81] He set up an assembly line process, aided by his wife, sons Pedro Nuno and José Antonio, his secretary José Seabra, Rabbi Kruger, and a few other refugees.[82]

According to the Bordeaux Register of Visas on the 17th were issued 247 Visas; on the 18th, 216; between the 19th and the 22nd, an average of 350 were written into the Register of Visas.[83]

The testimony from American writer Eugene Bagger is quite unfavourable regarding the efficiency of the "assembly line" set up by Sousa Mendes. Bagger says that on 18 June, he queued for a couple of hours at the Portuguese Consulate, hoping to get a visa. Bagger says that the pushing and elbowing drove him to despair and he gave up after a few hours. The next morning he joined again a mob of four hundred in front of the Portuguese Consulate. He waited in line from 09:00 till 11:00, again to no avail and he finally quit. He then decided to have a drink at the Hotel Splendid, where he found Sousa Mendes having an aperitif with a friend. Sousa Mendes told Bagger that he was tired from overworking the previous day, from the crowds and from the heat. Then, at Bagger's request, Sousa Mendes signed Bagger's passport and told him to go back to the consulate to have it stamped. To Bagger's surprise, he was then helped by M. Skalski, the Polish consul at Arcachon. At the consulate, M. Skalski was able to cut through the crowds and get Bagger's passports duly stamped.[84][85]

On 20 June, the British Embassy in Lisbon sent a letter to the Portuguese Foreign Office accusing Sousa Mendes of "deferring until after office hours all applications for visas" as well as "charging them at a special rate" and requiring at least one refugee "to contribute to a Portuguese charitable fund before the visa was granted."[86][87] This complaint from the British Embassy and the timing of Sousa Mendes' unilateral decision could not have been worse for Salazar and his carefully planned attempt to preserve Portuguese neutrality.[88] Salazar had instructed consulates in Spain and those in the south of France ― Bordeaux, Bayonne, Perpignan, Marseilles, Nice ― to issue transit visas to British citizens.[89]

Bordeaux was bombed by the Wehrmacht on the night of 19–20 June 1940.[90] In the morning, the demand for Portuguese visas intensified, not only in Bordeaux but also in nearby Bayonne, near the Spanish border. Sousa Mendes rushed to the Portuguese Consulate in Bayonne, which was under his jurisdiction, to relieve the Vice-Consul Faria Machado, who was refusing to grant visas to the crush of refugees.[91] However, Eugene Bagger says that, at Bayonne, he saw Sousa Mendes rushing out of the Portuguese Consulate, pursued by a mob, and that Sousa Mendes, holding his head between his hands, was crying "Go away! No more visas!", then jumped into a car and shot down the hill pursued by curses from the mass of visa seekers.[92]

In issuing visas at the Bayonne consulate, Sousa Mendes was aided by the Bayonne consular secretary, Manuel de Vieira Braga. Faria Machado, a Salazar loyalist in charge of the Bayonne consulate, reported this behaviour to Portugal's ambassador to Spain, Pedro Teotónio Pereira. Teotónio Pereria, a loyalist to the historic Anglo-Portuguese alliance,[93] promptly set out for the French-Spanish border to put a stop to this activity.[94] After observing Sousa Mendes' action, Teotónio Pereira sent a telegram to the Lisbon authorities in which he described Sousa Mendes as being "out of his mind" and also said that Sousa Mendes' "disorientation has made a great impression on the Spanish side with a political campaign against Portugal being created immediately accusing our country of giving shelter to the scum of the democratic regimes and defeated elements fleeing before the German victory."[95][96] He declared Sousa Mendes to be mentally incompetent and, acting on Salazar's authority, he invalidated all further visas.[97][upper-alpha 3] Teotónio Pereira's role in drawing Spain with Portugal into a truly neutral peninsular bloc in line with the allies' strategy was praised both by the British and the American ambassadors.[100][101]

Sousa Mendes continued on to Hendaye to assist there, thus narrowly missing two cablegrams from Lisbon sent on 22 June to Bordeaux, ordering him to stop even as France's armistice with Germany became official.[102] Sousa Mendes ordered the honorary Portuguese vice-consul in Toulouse, Emile Gissot, to issue transit visas to all who applied.[103]

The armistice was signed on 22 June. Under its terms, two-thirds of France was to be occupied by the Germans. On 26 June, the British Ambassador in Madrid wrote to London "The arrival of the Germans on the Pyrenees is a tremendous event in the eyes of every Spaniard. Will it mean the passage of troops through Spain to Portugal or Africa?"[104] Meanwhile, Teotónio Pereira, following Spanish protests,[105] declared the visas issued by Sousa Mendes to be null and void. The New York Times reported that some 10,000 persons attempting to cross over into Spain were excluded because authorities no longer granted recognition to their visas: "Portugal announced that Portuguese visas granted at Bordeaux were invalid, and Spain was permitting bearers of these documents to enter only in exceptional cases."[106] The Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported that small Portugal, whose population was just over seven million, had received an estimated two million applications for visas, permanent or transit. Most of them came from Frenchmen, Belgians, Dutch, and Poles in France who required Portuguese visas to pass through Spain. The applications must have included tens of thousands from Jews.[107]

On 24 June, Salazar recalled Sousa Mendes to Portugal, an order he received upon returning to Bordeaux on 26 June but he complied slowly, arriving in Portugal on 8 July.[108] Along the way, he continued issuing Portuguese visas to refugees now trapped in occupied France, and even led a large group to a remote border post that had not received Lisbon's order. His son, John-Paul Abranches, told the story: "As his diplomatic car reached the French border town of Hendaye, my father encountered a large group of stranded refugees for whom he had previously issued visas. Those people had been turned away because the Portuguese government had phoned the guards, commanding 'Do not honour Mendes's signature on visas.'... Ordering his driver to slow down, Father waved the group to follow him to a border checkpoint that had no telephones. In the official black limousine with its diplomatic license tags, Father led those refugees across the border toward freedom."[109]

After the intervention of Augusto d'Esaguy and Amzalak, most of the refugees issued visas by Sousa Mendes were allowed to continue on their way to Portugal[110] and were well received,[upper-alpha 4]

On 26 June, the main European office of HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) was authorized by Salazar to be transferred from Paris to Lisbon.[111][1] Salazar allowed Jewish relief organizations to set up offices in Lisbon and operate with little interference from the authorities. Initially this was done against the will of the British Embassy in Lisbon. The British feared that this would make the Portuguese people less sympathetic with the allied cause.[111]

Disciplinary proceeding and punishment

Upon returning to Portugal in early July 1940, Sousa Mendes was subjected to a disciplinary proceeding that has been described as "a severe crackdown"[112] and "a merciless disciplinary process."[113] The charges against him included: "the violation of Dispatch 14; the order to the consul in Bayonne to issue visas to all those who asked for them 'with the claim that it was necessary to save all these people'; the order given to the consul in Bayonne to distribute visas free of charge; the permission given by telephone to the consul in Toulouse that he could issue visas; acting in a way that was dishonourable for Portugal vis-à-vis the Spanish and German authorities."; the confessed passport forgery to help Luxembourger Paul Miny escape army mobilization; abandoning his post at Bordeaux without authorization and extortion, this latest one based on the accusation made by the British Embassy.[103] Rui Afonso wrote in 1990's Injustiça (Injustice) that the disciplinary action against Sousa Mendes was less due to the granting of too many visas and more the result of his various financial intrigues such as requiring applicants to donate to charity, and his personal use of public monies. Afonso softened this stance in his 1995 book Um Homem Bom (One Good Man). Historian Avraham Milgram observes that Afonso holds a minority view: the mainstream view is that Sousa Mendes was disciplined for the granting of too many visas, in violation of his instructions.[6]

The accusation asserted that "an atmosphere of panic does in fact provide an extenuating circumstance for the acts committed by the Defendant during the month of June and possibly even for those committed in the second half of the month of May...,however, the acts committed during that period are no more than a repetition or extension of a procedure that already existed, for which the same extenuating circumstance cannot be invoked. There had been infractions and repetitions long before 15 May...this is the 4th case of disciplinary proceedings brought against the Defendant".[45]

Sousa Mendes submitted his response to the charges on 12 August 1940, in which he clarified his motivation:

It was indeed my aim to save all those people whose suffering was indescribable: some had lost their spouses, others had no news of missing children, others had seen their loved ones succumb to the German bombings which occurred every day and did not spare the terrified refugees....There was another aspect that should not be overlooked: the fate of many people if they fell into the hands of the enemy....eminent people of many countries with whom we have always been on excellent terms: statesmen, ambassadors and ministers, generals and other high officers, professors, men of letters,...officers from armies of countries that had been occupied, Austrians, Czechs and Poles, who would be shot as rebels; there were also many Belgians, Dutch, French, Luxembourgers and even English...Many were Jews who were already persecuted and sought to escape the horror of further persecution. Finally an endless number of women attempting to avoid being at the mercy of Teutonic sensuality. I could not differentiate between nationalities as I was obeying the dictates of humanity that distinguish between neither race nor nationality; as for the charge of dishonourable conduct, when I left Bayonne I was applauded by hundreds of people, and through me it was Portugal that was being honoured...."[114]

On 19 October 1940, the verdict was handed down: "disobeying higher orders during service."[115] The disciplinary board recommended a demotion.[116] On 30 October 1940, Salazar rejected this recommendation and imposed his own sentence: "I sentence Consul First Class, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, to a penalty of one year of inactivity with the right to one half of his rank's pay, being obliged subsequently to be retired."[117] He further ordered that all files in the case be sealed.[117]

There was also an unofficial punishment: the blacklisting and social banishment of Aristides de Sousa Mendes and his family. "My grandfather...knew there would be some retribution, but to lose everything and have the family disgraced, he never thought it would go that far", said the hero's grandson, also named Aristides.[118] The family took meals at the soup kitchen of the Jewish community of Lisbon. When told that the soup kitchen was intended for refugees, Sousa Mendes replied, "But we too are refugees."[119]

Sousa Mendes was listed in the Portuguese Consular and Diplomatic Yearbook until 1954.[120][121] After the one year punishment with half-pay, he received a monthly payment of 1,593 Portuguese escudos per month.[2][3][4] According to Rui Afonso, "although it was not a salary of a prince, one should not forget that at that time, in Portugal, the monthly salary of a school teacher was only 500 Escudos".[2] When he died, in 1954 he was receiving a monthly salary of 2,300 escudos.[2][5]

According to Milgram, Mendes' actions, while exceptional in its scope, were not unique, as issuing visas in contravention of the Portuguese government's instructions occurred at other Portuguese consulates as well.[53]

After the war, with the victory of the Allied forces over the Axis, Salazar took credit for Portugal having received the refugees,[122] and the Portuguese history books were written accordingly. Manuela Franco, Director of the Portuguese Foreign Ministry archives, stated in 2000 that "the image of 'Portugal, a safe haven' was born then in Bordeaux, and it lasts to this day."[123]

Last years

Throughout the war years and beyond, Sousa Mendes was optimistic that his punishment would be reversed and his deed would be recognized.[82] In a 1945 letter to the Portuguese Parliament, he explained that he had disobeyed orders because he had considered them to be unconstitutional, as the Portuguese Constitution forbade discrimination on the basis of religion. This was the first time that Sousa Mendes used this line of argument and he explained that he hadn't used it before because, being a public official, he did not want to attract publicity and therefore compromise Portugal's neutrality.[124][125]

In 1941, Sousa Mendes applied to the Portuguese Bar Association and he was admitted to the bar to practice law. But in 1942, he wrote a letter to the bar, explaining that since he was living in a small village, in his mansion at Passal, he was not able to work as a lawyer and he asked for his license to be cancelled.[126] Later, in 1944, he asked for readmission, which was granted.[127][128] Then, as a lawyer, he won a court case, in which he defended two of his sons, Carlos and Sebastian, who were being deprived of Portuguese citizenship because they had enlisted in the allied armed forces in the UK.[129]

Just before the war's end in 1945, Sousa Mendes suffered a stroke that left him at least partially paralysed and unable to work.[130][131]

In 1946, a Portuguese journalist tried to raise awareness for Sousa Mendes outside of Portugal by publishing the facts under a pseudonym in a US newspaper.[132] Sousa Mendes' wife Angelina died in 1948.[133]

The following year he married his former mistress Andrée Cibial, with whom he had a daughter, Marie-Rose. Cibial soon clashed with Sousa Mendes' sons and the couple moved to Cabanas de Viriato. It did not take long for Andrée to show to Sousa Mendes' sons that they were not welcome at Passal, and soon the youngsters were separated from their father.[134] John Paul joined other brothers and sisters already living in California. Pedro Nuno left for the Congo. Geraldo went to Angola, and Clotilde went to Mozambique.[134] On account of Andrée`s spending habits, Sousa Mendes also started to have disputes with his brothers César and João Paulo and his cousin Silvério.[135]

As his financial situation deteriorated, he would sometimes write to the people he had helped asking for money.[136] On one occasion, Maurice de Rothschild sent him 30,000 Portuguese escudos, a considerable amount of money in Portugal at that time.[137]

In 1950, Sousa Mendes and Cibial travelled to France. Their daughter, Marie-Rose, had been raised in France by her aunt and uncle and was ten when she met her father for the first time. Her parents began spending the summer months with her each year.[138]

In his final years, Sousa Mendes was abandoned by most of his colleagues and friends, and at times was blamed by some of his close relatives.[139] His children moved to other countries in search of opportunities they were now denied in Portugal, although by all accounts they never blamed their father or regretted his decisions.[140] He asked his children to help clear the family name and make the story known.[140] In 1951, one of his sons, Sebastião, published a novella about the Bordeaux events, Flight Through Hell.[141][142] César de Sousa Mendes, twin brother of Aristides, did everything he could to try to get Salazar to reverse his punishment, but to no avail.[143] But Sousa Mendes never regretted his action. "I could not have acted otherwise, and I therefore accept all that has befallen me with love,"[144] he reportedly said. To his lawyer he wrote: "In truth, I disobeyed, but my disobedience does not dishonour me. I did not respect orders that to me represented the persecution of true castaways who sought with all their strength to be saved from Hitler's wrath. Above the order, for me, there was God's law, and that's the one I have always sought to adhere to without hesitation. The true value of the Christian religion is to love one's neighbour."[145]

Sousa Mendes always lived with financial problems and Cibial's spending habits aggravated the situation. The couple eventually ended up selling all their furniture from their family mansion and raising debts with banks.[146] Sousa Mendes died in poverty[147] on 3 April 1954, owing money to his lenders and still in disgrace with his government. The only person present when he died was one of his nieces.[148]

Number of visa recipients

There are different views regarding the number of visas issued by Sousa Mendes. It has been widely published that Sousa Mendes saved 30,000 refugees, of which 10,000 were Jews. Historian Avraham Milgram thinks that it was probably Harry Ezratty who was the first to mention in an article published in 1964 that Sousa Mendes had saved 30,000 refugees, of which 10,000 were Jews, a number which has since been repeated automatically by journalists and academics. Milgram says that Ezratty, imprudently, took the total number of Jewish refugees who passed through Portugal and ascribed it to the work of Aristides de Sousa Mendes.[6] Milgram thinks that "the discrepancy between the reality and the myth of the number of visas granted by Sousa Mendes is great."[6] To make his point, Milgram cross-checked the numbers from the Bordeaux visa register entry books with those of the HICEM reports, and although he acknowledged that visas delivered in the cities of Bayonne, Hendaye and Toulouse cannot be exactly determined, he asserted that the numbers are exaggerated.

In 2011, Milgram published a densely researched book, Portugal, Salazar and the Jews and for a second time he asserted that "authors, especially those who wish to sing the praises of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, tend to overstate the number of visas with figures that do not satisfy research criteria, but rather correspond to their wishful thinking".[149]

A similar opinion is shared by British historian Neill Lochery. In 2011, Lochery quoted Milgram's numbers, and to further support his view he also cross checked numbers with the Portuguese Emigration Police files and he also concluded that the numbers usually published by popular literature are a "myth".[150] Both these historians concur that this does not diminish the greatness of Sousa Mendes's gesture. Rui Afonso, the first Sousa Mendes biographer, also says that José Seabra, Sousa Mendes' deputy at Bordeaux, always testified that the order of magnitude of irregular visas issued at Bordeaux was within hundreds.[151]

In 2008, the Portuguese ambassador João Hall Themido took a stand affirming that in his opinion, the Sousa Mendes story was a "myth invented by Jews" and asserting his disbelief in the 30,000 figure.[152][153]

A similar path was followed by Portuguese Professor José Hermano Saraiva, a former António de Oliveira Salazar and Marcelo Caetano minister, and a great admirer of Salazar. Professor Saraiva also asserts that it was the Portuguese neutrality and hospitality that saved thousands of lives throughout the war—that a stamp in a passport would never be enough to save anyone should the Portuguese Government at that time have decided to follow a different path.[154][155]

A complex operation was needed to house and feed all those people moving and staying in Portugal for a considerable period of time. According to Saraiva and some other historians, Leite Pinto, former Portuguese minister of education, should also be given credit for most refugees saved during the war. Professor Baltasar Rebelo de Sousa mentioned the "Leite Pinto operation", that used sealed trains to bring thousands of refugees into Portugal, and praised this operation in a tribute to Leite Pinto.[156] Forced by the circumstances, several Portuguese assistance associations, sponsored by the government, were then created in Portugal for the integration and hosting of this large number of refugees, mostly Jews, many hosted and received by Portuguese families.[157]

On the other hand, as a reaction to Milgram's assertions, French writer, Eric Lebreton, in 2010, argued that "Milgram did not account for the visas that were delivered in Bayonne, Hendaye and Toulouse, and on the other hand, he [Milgram] holds firm to the number presented in the one surviving registry book of José Seabra (Sousa Mendes' deputy). According to Lebreton, Milgram's article, while very interesting in other ways, lacks details and knowledge on this point."[7]

Holocaust scholar Yehuda Bauer characterized Sousa Mendes' deed as "perhaps the largest rescue action by a single individual during the Holocaust."[158]

In 2015, Olivia Mattis, musicologist and Board President of the Sousa Mendes Foundation in the United States, published the findings of the Sousa Mendes Foundation stating that "tens of thousands" of visa recipients is a figure in the correct order of magnitude.[8]

Posthumous rehabilitation and recognition

After Sousa Mendes' death in 1954, his children[159] worked tirelessly to clear his name and make the story known. In the early 1960s, a few articles began appearing in the U.S. press.[160] On 21 February 1961, David Ben-Gurion, the Prime Minister of Israel, ordered that twenty trees be planted by the Jewish National Fund in memory of Sousa Mendes and in recognition of his deed.[161] In 1963, Yad Vashem began recognizing Holocaust rescuers as Righteous Among the Nations, and Sousa Mendes, in 1966, was among the earliest to be so named, thanks in large part to the efforts of his daughter Joana.[162] But with Salazar still in power, "the diplomat and his efforts remained unknown even in his own country for years."[163] Moreover, Salazar's representatives gave statements to the press casting doubt on Sousa Mendes' heroism by denying that Circular 14 had ever existed.[164]

Following the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal, when the Estado Novo dictatorship was overthrown and democracy was established, Dr. Nuno A. A. de Bessa Lopes, a Portuguese government official, took the initiative of reopening the Sousa Mendes case and making recommendations.[165] His assessment, based on his viewing of previously sealed government files, was that the Salazar government had knowingly sacrificed Sousa Mendes for its own political ends, and that the verdict and punishment were illegal and should be overturned.[166] "Aristides de Sousa Mendes was condemned for having refused to be an accomplice to Nazi war crimes,"[167] the report concluded. The report was suppressed by the Portuguese government for over a decade.[168] "The failure to act on the Lopes report reflects the fact that there was never a serious purge of Fascist supporters from government ministries,"[169] explained journalist Reese Erlich.

In 1986, inspired by the election of Mário Soares, a civilian president in Portugal, Sousa Mendes' youngest son John Paul began to circulate a petition to the Portuguese president within his adopted country, the United States. "I want people in Portugal to know who he was, what he did, and why he did it,"[170] explained John Paul. He and his wife Joan worked with Robert Jacobvitz, an executive at the Jewish Federation of the Greater East Bay in Oakland, California, and lawyer Anne Treseder to create the "International Committee to Commemorate Dr. Aristides de Sousa Mendes."[171] They were able to gain the support of two members of the California delegation of the United States House of Representatives, Tony Coelho and Henry Waxman, who introduced a resolution in Congress to recognize his humanitarian actions.[172] That same year, Sousa Mendes was honored at the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, where John Paul and his brother Sebastião gave impassioned speeches and Waxman spoke as well.[173]

In 1987, the Portuguese Republic began to rehabilitate Sousa Mendes' memory and granted him a posthumous Order of Liberty medal, one of that country's highest honors, although the consul's diplomatic honors still were not restored. In October of that year, the Comité national français en hommage à Aristides de Sousa Mendes was established in Bordeaux, France, presided over for the next twenty-five years by Manuel Dias Vaz.[174]

On 18 March 1988, the Portuguese parliament officially dismissed all charges, restoring Sousa Mendes to the diplomatic corps by unanimous vote,[175] and honoring him with a standing ovation. He was promoted to the rank of Ministro Plenipotenciário de 2ª classe and awarded the Cross of Merit. In December of that year, the U.S. Ambassador to Portugal, Edward Rowell, presented copies of the congressional resolution from the previous year to Pedro Nuno de Sousa Mendes, one of the sons who had helped his father in the "visa assembly line" at Bordeaux, and to Portuguese President Mário Soares at the Palácio de Belém. In 1994, former President Mário Soares dedicated a bust of Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux, along with a commemorative plaque at 14 quai Louis‑XVIII, the address at which the consulate at Bordeaux had been located.[176]

In 1995, Portugal held a week-long National Homage to Sousa Mendes, culminating with an event in a 2000-seat Lisbon theater that was filled to capacity.[177] A commemorative stamp was issued to mark the occasion.[178] The Portuguese President Mário Soares declared Sousa Mendes to be "Portugal's greatest hero of the twentieth century."[179]

In 1997, an international homage to Sousa Mendes was organized by the European Union in Strasbourg, France.[180]

Casa do Passal, the mansion that Sousa Mendes had to abandon and sell in his final years, was left for decades to decay into a "ghost of a building,"[181] and at one time was to be razed and replaced by a hotel. However, with reparation funds given by the Portuguese government to Sousa Mendes' heirs in 2000, the family decided to create the Fundação Aristides de Sousa Mendes.[182] With assistance from government officials, the foundation purchased the family home in order to develop a museum in his honor.[183]

In April 2004, to mark the 50th anniversary of Sousa Mendes' death, the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation and the Angelo Roncalli Committee organized more than 80 commemorations around the world. Religious, cultural and educational activities took place in 30 countries on five continents, spearheaded by João Crisóstomo.[184]

On 11 May 2005, a commemoration in memory of Aristides de Sousa Mendes was held at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris.

On 14 January 2007, Sousa Mendes was voted into the top ten of the poll show Os Grandes Portugueses (the greatest Portuguese). On 25 March 2007, when the final rankings were announced, it was revealed that Sousa Mendes came in third place overall, behind communist leader Álvaro Cunhal (runner-up) and the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar (winner).[185]

In February 2008, Portuguese parliamentary speaker Jaime Gama led a session which launched a virtual museum, on the Internet, offering access to photographs and other documents chronicling Sousa Mendes' life.[186]

On 24 September 2010, the Sousa Mendes Foundation was formed in the United States with the purpose of raising money for the conversion of the Sousa Mendes home into a museum and site of conscience, and in order to spread his story throughout North America.[187]

On 3 March 2011, the Casa do Passal was designated a National Monument of Portugal.[188]

In May 2012, a campaign was launched to name a Bordeaux bridge after Sousa Mendes.[189]

In January 2013, the United Nations headquarters in New York honored Sousa Mendes and featured Sousa Mendes visa recipient Leon Moed as a keynote speaker during its International Days of Commemoration of Victims and Martyrs of the Holocaust.[190]

On 20 June 2013, a big rally was held in front of the Sousa Mendes home, Casa do Passal,[191] to make a plea for its restoration. An American architect, Eric Moed,[192] spearheaded the event, attended by visa recipient families from all over the world, including his grandfather Leon Moed.[193] At this event, a representative of the Portuguese Ministry of Culture publicly pledged $400,000 in European Union funds for the restoration effort.[194]

On 20 October 2013, a playground in Toronto, Canada was renamed in honor of Sousa Mendes.[195] That same month, the Portuguese airline Windavia named an airplane after him.[196] In December 2013, a letter that Sousa Mendes had penned to Pope Pius XII in 1946, begging for help from the Catholic Church, was delivered to Pope Francis.[197]

In late May 2014, construction began at the Casa do Passal with funds from the European Union.[198]

In September 2014, TAP Air Portugal has named its newest Airbus A319 after Aristides de Sousa Mendes, as a tribute to the Portuguese Consul.[199]

An oratorio entitled "Circular 14: The Apotheosis of Aristides", by Neely Bruce, detailed the life of Sousa Mendes. The first performance was held on 24 January 2016.[200]

Notable people issued visas by Sousa Mendes

- Academics

- Sylvain Bromberger, professor emeritus of philosophy, MIT[201]

- Roger Hahn, professor emeritus of history, University of California, Berkeley[202]

- Lissy Feingold Jarvik, professor emeritus of psychiatry, UCLA[203]

- Daniel Mattis, professor emeritus of physics, University of Utah[204]

- Creative artists

- Hélène de Beauvoir, painter, sister of Simone de Beauvoir[205]

- Salvador Dalí, the painter, whose Russian wife Gala was directly threatened by Dispatch 14[206]

- Marcel Dalio, actor in Casablanca[207]

- Salamon Dembitzer, author of Visas to America[208]

- Otto Eisler, playwright, who moved to Hollywood and became the screenwriter Osso van Eyss[209]

- Grzegorz Fitelberg, conductor and violinist[210]

- Jean-Michel Frank, interior designer[211]

- Simone Gallimard, publisher[212]

- Colette Gaveau, pianist[213]

- Nelly de Grab, fashion designer[214]

- Hugo Haas, actor[215]

- Maria Lani, actress and artist's model for Matisse, Chagall and others[216]

- Madeleine Lebeau, actress in Casablanca[207]

- Alexander Liberman, sculptor and artistic director of Vogue magazine[217]

- Witold Małcużyński, pianist[213]

- Hendrik Marsman, poet[218]

- Leon Moed, architect[219]

- Robert Montgomery, actor[220]

- Carlos Radzitzky, poet and jazz critic[221]

- H. A. Rey and Margret Rey, authors/illustrators of Curious George[222]

- Claire Rommer, actress[223]

- Paul Rosenberg, art dealer, and family[224]

- Antoni Słonimski, poet[225]

- Tereska Torrès, novelist[226]

- Julian Tuwim, poet[225]

- Jean-Claude van Itallie, actor and playwright[227]

- King Vidor, film director[228]

- Journalists

- Hamilton Fish Armstrong[229]

- Eugene Szekeres Bagger[230]

- Marian Dąbrowski[231]

- Boris Smolar[232]

- Sonia Tomara[233]

- Political figures

- Joseph Bech, Foreign Minister of Luxembourg[234]

- Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg[235]

- Pierre Dupong, Prime Minister of Luxembourg[236]

- Otto von Habsburg, nemesis of Hitler and heir to the Austrian throne[237]

- Maurice de Rothschild, art collector, vintner, financier, Senator of France[238]

- Henri Torres, French lawyer and key supporter of Charles de Gaulle[239]

- Albert de Vleeschauwer, a leading member of the Belgian government in exile[240]

- Refugee advocates

- Religious leaders

See also

- Individuals and groups assisting Jews during the Holocaust

- Righteous Among the Nations

- Carlos Sampaio Garrido – Portuguese diplomat in Budapest during World War II

- Augusto Isaac de Esaguy

Explanatory notes

- Sousa Mendes wanted to raise funds for an institution that helped orphans of war in Rio, Brazil. He became aware that the Cult of the Holy Spirit, an organization supported by the Oakland American-Portuguese community, had decided to donate funds to the American Red Cross and to the Sacred Heart Hospital in Hanford, California, instead of donating funds to the organization he favoured. [27] He decided to publish an article in a local newspaper accusing the directors of the Cult of the Holy Spirit of lack of love and respect for Portugal and he [27] also banned the Portuguese notaries from performing any further services to the consulate. [28]The directors of the Cult of the Holy Spirit reacted and also published an article and the dispute reached the form of insults, published by both sides.[29] A significant part of the local Portuguese community took sides with Sousa Mendes and defended him. The Portuguese Ministry sent telegrams to Mendes ordering him to stop publishing more articles in the newspapers and reminding him that the local Portuguese community was free to choose the institutions to whom they elected to donate funds, and that his decision to ban the notaries was illegal and should be reverted immediately.[30] He was also warned that the American authorities would also not approve of his conduct.[31] Mendes ignored the Ministry and kept on with the dispute. He ended up with his exequatur cancelled and being transferred to Maranhão in Brazil.[32]For a complete description see Madeira.[33] Fralon asserts that in this episode, Mendes had stood up for his poorest compatriots when they protested against the working conditions to which they were subjected by their employers, who were also Portuguese, but much better off."[24] However, this assertion is not confirmed either by primary sources (newspaper articles) or by other published sources.

- At this time rumours abounded in the diplomatic circles of a possible "coup" in Lisbon, promoted by the Germans or a German attack on Portugal in the Axis interest.[72]

- Two days later, on 26 June 1940, the Spanish Minister Serrano Suñer told Pereira that Hitler would no longer tolerate the independent existence of an ally of Britain on the continent and Spain would soon be forced to permit passage of German troops to invade Portugal.[98][99] Pereira countered with diplomatic actions that culminated in an additional protocol to the Iberian Pact, signed on 29 July 1940, a key contribution to a neutral peninsular bloc.

- Testimonial from American writer Eugene Bagger: Two Portuguese frontier guards, with rifles flung across their backs, came walking down the line of cars. When they saw our number plate they stopped, all wrapped up in smiles. "Inglês?" "Americano e Inglesa." "Aliados!" We shook hands. It was a new world, a world of friends... The soldiers carried large open bags and held them out to the refugees. Round golden-brown loaves of freshly baked Portuguese bread, still warm from the oven; the best white bread in the world, as we were to find. Tins of delicious large sardines. Bars of chocolate. The ladies distributed sweet crackers and tins of condensed milk for the children. As long as we live we shall not forget the Portuguese officials of Vilar Formoso.... They fed all comers, regardless of nationality; those who had money paid what they chose to; most refugees had no money, and paid nothing.

References

- Gallagher 2020, p. 124.

- Afonso 1995, p. 257.

- Lochery 2011, p. 49.

- Wheeler 1989, p. 128.

- "Abranches, Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e – Personal File". Arquivo Digital – Ministério das Finanças / (in Portuguese). Portuguese Ministry of Finance. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- Milgram 1999, pp. 123–156.

- Lebreton p.231

- Olivia Mattis, "Sousa Mendes's List: From Names to Families", Prism: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Holocaust Educators 7 (Spring 2015), note 3.

- "Aristides de Sousa Mendes". Yad Vashem. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- Gallagher 2020, p. 122.

- Gallagher 2020, p. 126.

- "Portugal finally recognises consul who saved thousands from Holocaust". BBC. 17 June 2020.

- "Pólo Museológico, Vilar Formoso Fronteira da Paz – Memorial aos Refugiados e ao Cônsul Aristides de Sousa Mendes". Almeida Município. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Fralon 2000, p. 1.

- Fralon 2000, p. 6.

- Fralon 2000, p. 4.

- Fralon 2000, p. 20.

- Fralon 2000, p. 25.

- Fralon 2000, p. 7.

- Fralon 2000, p. 14.

- Madeira 2013, p. 259.

- Reese Ehrlich, "A Hero Remembered", Hadassah Magazine (November 1987): 26.

- Fralon 2000, p. 17.

- Fralon 2000, p. 18.

- Madeira 2007, pp. 191–203.

- Afonso 1995, p. 193.

- Madeira 2007, p. 194.

- Madeira 2007, pp. 197–198.

- Madeira 2007, p. 195.

- Madeira 2007, pp. 198–199.

- Madeira 2007, p. 200.

- Madeira 2007, p. 201.

- Madeira 2007, p. 189-203.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes, "A Lingua Portuguesa na Universidade da California", O Lavrador Português, November 28, 1923, p.1.

- Fralon 2000, p. 19.

- Afonso 1995, p. 195.

- Fralon 2000, p. 21.

- Fralon 2000, p. 39.

- Madeira 2013, pp. 415–425.

- Milgram 2011, p. 63–64.

- Milgram 1999, p. page number needed.

- Dez anos de Politica Externa, Vol 1, pag 137. Edição Imprensa Nacional 1961

- Pimentel 2006, p. 87.

- Pimentel 2006, p. 46-52.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Portugal, Spared Lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II, Documentary Exhibition, Catalogue, September 2000, p.81.

- Spared Lives pp.81-82

- Lochery 2011, p. 42-43.

- Milgram 2011, p. 266.

- Milgram 2011, p. 13.

- Milgram 2011, p. 11.

- Milgram 2011, p. 70.

- Paldiel 2007, p. 74.

- Milgram 2011, p. 89.

- Afonso 1995, pp. 29–39.

- Fralon 2000, p. 48.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Portugal, Spared Lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II, Documentary Exhibition, Catalogue, September 2000, p.36.

- Mordecai Paldiel as cited in Gerald Clark, "The Priceless Signature of Aristides de Sousa Mendes", Reader's Digest (December 1988): 66.

- Afonso 1995, p. 39.

- Fralon, p. 48 and "Miny," Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Afonso 1995, p. 63.

- Afonso 1995, p. 52.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Portugal, Spared Lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II, Documentary Exhibition, Catalogue, September 2000, p.98.

- Gallagher 2020, p. 123.

- "Albuquerque-Ertag-Flaksbaum-Landesman-Untermans," Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Fralon, p.109 and "Quittner," Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Lansing Warren, "Refugee Millions Suffer in France; Roads From Paris to Bordeaux Jammed With Wanderers Pitifully in Need", The New York Times, 19 June 1940.

- Gerald Clark, "The Priceless Signature of Aristides de Sousa Mendes", Reader's Digest (Canadian edition, December 1988): 61-62.

- Mordecai Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, Jerusalem: Collins, 2007, p.264.

- Afonso 1995, p. 65.

- Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations, p.264.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes to Silvério de Sousa Mendes, 13 June 1940, "De Winter," Archived 2014-03-12 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Stone, Glyn (1994). The Oldest Ally: Britain and the Portuguese Connection, 1936-1941. Royal Historical Society. ISBN 9780861932276.

- Rezola, Maria Inácia. "The Franco–Salazar Meetings: Foreign policy and Iberian relations during the dictatorships (1942-1963)". e-Journal of Portuguese History. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Madeira 2013, p. 458.

- Madeira 2013, p. 459.

- AHDMNE, Telegramas expedidos, Consulado de Portugal em Bayonne, Lisboa, t de Oliveira Salazar para Faria Machado, 13.06.1940.

- Spared Lives and Lochery p. 48

- César de Sousa Mendes (nephew), as cited in Wheeler, "A Hero of Conscience", p.69.

- Pedro Nuno de Sousa Mendes, as cited in Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations, p.265.

- Mordecai Paldiel, Diplomat Heroes of the Holocaust, p.76.

- Robert Jacobvitz, "Reinstating the Name and Honor of a Portuguese Diplomat Who Rescued Jews During World War II: Community Social Work Strategies", Journal of Jewish Communal Service, (Spring 2008): 250.

- Wheeler 1989, pp. 119–139.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Portugal, Spared Lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II, Documentary Exhibition, Catalogue, September 2000, p.36.

- Bagger, Eugene (1941). For the Heathen are Wrong: An impersonal autobiography. Little, Brown and Co; 1st edition. pp. 153–155.

- Afonso 1995, p. 104.

- Lochery 2011, p. 47.

- Milgram 2011, p. 47.

- Lochery 2011, p. 46.

- Milgram 1999, p. 20.

- Christiano D'Adamo, "The Bombardments of Bordeaux," Regia Marina Italiana. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations, p.265.

- Bagger, Eugene (1941). For the Heathen are Wrong: An impersonal autobiography. Little, Brown and Co; 1st edition. p. 160.

- Hoare 1946, p. 320, Hayes, Carlton J.H. (2009). Wartime mission in Spain, 1942-1945. Macmillan Company 1st Edition. p. 313. ISBN 9781121497245.

- Fralon 2000, p. 89.

- Spared Live – Telegram sent by Teotónio Pereira to Lisbon

- Pedro Teotónio Pereira telegram to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lisbon, late June 1940, as cited in Mordecai Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations; Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2007, p.266.

- Fralon, p.105. The Jewish Virtual Library article notes that a Spanish newspaper headline the next day announced the sudden insanity of "the Consul of Portugal in Bayonne", an ironic error that labelled Sousa Mendes' accuser as the one who had lost his faculties.

- Payne 2008, p. 75.

- Tusell 1995, p. 127.

- Hayes 1945, p. 36.

- Hoare 1946, p. 45.

- Fralon 2000, p. 91.

- Fralon 2000, pp. 106–107.

- Hoare 1946, p. 36.

- Spared Live – Telegram sent by Teotónio Pereira to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lisbon, late June 1940.

- "American Writers Escape Into Spain", The New York Times, 26 June 1940, p.15.

- "Anti-semitic Agitation Flared in Paris on Eve of Nazi Entry; 50,000 Jews Fled Capital". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. June 28, 1940. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- Ronald Weber, The Lisbon Route: Entry and Escape in Nazi Europe, Lanham: Ivan R. Dee, p.10.

- John Paul Abranches, "A Matter of Conscience", Guideposts (June 1996): 2-6.

- Milgram 2011, p. 136.

- Lochery 2011.

- Milgram 2011, p. 289.

- Margarida Ramalho, Lisbon: City During Wartime, p.12.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes statement of defence, 12 August 1940, as cited in Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations, p.267.

- Fralon, p.114.

- Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations, p.268.

- Fralon, p.115.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes (grandson) as cited in Mark Fonseca Rendeiro, "The Bravery of a Portuguese War Hero Resonates Today," The Guardian, 29 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Fralon p.118 and Isaac Bitton testimonial, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 17 May 1990, 6:30-9:45. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Anuário Diplomático e Consular Português - 1954. Portugal: Imprensa Nacional – Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros. 1954. p. 270.

- Sousa Mendes, Alvaro. "NOTA BIOGRÁFICA – ARISTIDES DA SOUSA MENDES" (PDF). Ministério das Finanças – Portugal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Fralon, pp.122 and 126. Sousa Mendes' accuser Teotónio Pereira also took some of the credit: Fralon, p.106.

- Manuela Franco, "Politics and Morals" in Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Portugal, Spared Lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II, Documentary Exhibition, Catalogue, September 2000, p.19.

- Afonso 1995, pp. 283–284.

- Wheeler 1989, p. 129.

- "Letter from Sousa Mendes to the Portuguese Bar Association". Sousa Mendes Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Afonso, Rui p. 269

- Sousa Mendes`complete track record of admissions can be found at the Portuguese Bar Association summarizes Sousa Mendes’ several admissions. An online version can be found at the Sousa Mendes Virtual Museum in this link .

- Afonso 1995, pp. 269–270.

- Afonso 1995, p. 275.

- A letter written by Sousa Mendes, saying he is ill and unable to work, can be found at the Portuguese Bar Association, an online copy can be found in the Sousa Mendes Virtual Museum at

- Miguel Valle Ávila, "Was Lisbon Journalist 'Onix' Portugal's Deep Throat? Aristides de Sousa Mendes Defended in the US Press in 1946", The Portuguese Tribune (1 October 2013): 28.

- Afonso 1995, p. 294.

- Afonso 1995, p. 303.

- Afonso 1995, pp. 306–307.

- Fralon 2000, pp. 132.

- Afonso 1995, pp. 289–290.

- Afonso 1995, p. 307.

- Luis-Filipe de Sousa Mendes, "Words of Remembrance," Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine 1987, Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Luis-Filipe de Sousa Mendes, "Words of Remembrance" Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, 1987, Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Michael d'Avranches [pseudo. Sebastião de Sousa Mendes], Flight Through Hell, New York: Exposition Press, 1951.

- Sebastian Mendes, "Lifelong Champion of Major Holocaust Hero Dies", 17 December 2006. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Fralon, pp.124-25.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes, as cited in Paldiel, The Righteous Among the Nations, p.268.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes, letter to his lawyer Palma Carlos, as cited in Manuel Dias Vaz, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, héros "rebelle", Juin 1940, Souvenirs et Témoignages, Quercy : Éditions Confluences, 2010, p.26.

- Fralon 2000, pp. 136–138.

- Portugal finally recognises consul who saved thousands from Holocaust, by James Badcock, BBC news, 17 June 2020.

- Fralon 2000, p. 142.

- Milgram 2011, p. 121.

- Lochery 2011, p. 44.

- Afonso 1995, p. 283.

- Themido, J. Hall (2008). Uma Autobiografia Disfarçada – A Mitificação de Aristides de Sousa Mendes. Lisbon: Instituto Diplomático – Portuguese Foreign Office. ISBN 9789898140012.

- Themido, João Hall (Nov 1, 2008). "Aristides de Sousa Mendes é um "mito criado por judeus"". Expresso (Portuguese newspaper) (in Portuguese). Lisbon. Retrieved 19 March 2014. – Expresso is the biggest Portuguese weekly newspaper.

- Saraiva, José Hermano (2007). Album de Memórias (in Portuguese). Lisbon: O SOL é essential S.A. ISBN 978-989-8120-00-7.

- Saraiva, José Hermano (20 July 2012). "Recorde a grande entrevista de José Hermano Saraiva ao SOL (2ª parte)". Sol (in Portuguese). Lisbon. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2014. – Sol is the second portuguese weekly newspaper.

- HOMEM DA CIÊNCIA E DA CULTURA in No centenário do nascimento de Francisco de Paula leite Pinto, Memória 2, Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, 2003.

- Portugal e os refugiados judeus provenientes do território alemão (1933–1940), author: Ansgar Schaefer, Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2014

- Yehuda Bauer, A History of the Holocaust, Franklin Watts, 2002, p.235.

- Particularly active were Sebastião, Joana, John Paul, Luis Felipe and Pedro Nuno.

- Examples include Guy Wright, "Straightening the Record on Dictator and a Hero", San Francisco New Call Bulletin, 4 May 1961 and an article in the Portuguese press of Massachusetts: "Um português salvou 10.000 judeus no tempo da guerra, mas foi castigado", Diário de Noticias (New Bedford, Massachusetts), 19 May 1961, pp.1 and 5.

- "Um português salvou 10.000 judeus no tempo da guerra, mas foi castigado", Diário de Noticias (New Bedford, Massachusetts), 19 May 1961, p.5.

- Robert McG. Thomas Jr., "Joana Mendes, 77, Champion of Father's Effort to Save Jews," The New York Times, 10 April 1997, obituaries, C29. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Portugal's Unforgettable Forgotten Hero," USC Shoah Foundation, 10 July 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Anibal Martins, "Ainda o Caso do Consul Sousa Mendes", letter to the editor, Diário de Noticias (New Bedford, Massachusetts), 13 October 1967, p.2.

- Reese Erlich, "Mending the Past; Belatedly, the righteous Dr. Mendes has been recognized. Full recognition, however, has yet to come", Moment, June 1987, p.52.

- Fralon, p.151.

- Bessa Lopes report as cited in Fralon, p.152.

- Erlich, Reese (19 May 1987). "Forgotten Hero: Portugal's President to Honor Diplomat Who Defied Holocaust". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Erlich, "Mending the Past", p.53.

- John Paul Abranches, as cited in Erlich, "Mending the Past", p.54.

- Robert Jacobvitz, "Reinstating the Name and Honor of a Portuguese Diplomat Who Rescued Jews During World War II: Community Social Work Strategies", Journal of Jewish Communal Service, Spring 2008 and Jonathan Curiel, John Paul Abranches, Hero Envoy's Son, Dies," San Francisco Chronicle, 19 February 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "70 Lawmakers Ask Portugal to Honor Posthumously a Portuguese Diplomat Who Saved Jews in WWII," Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 2 September 1986. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Video of speeches at Simon Wiesenthal Center followed by television coverage of the event, Los Angeles, 1986. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Comité National Français en hommage à Aristides de Sousa Mendes". Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Assembleia da República (April 26, 1988). "Reintegração na carreira diplomática, a título póstumo, do ex-cônsul-geral de Portugal em Bordéus Aristides de Sousa Mendes". Diário da República Electrónico. Portuguese Republic. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Fralon, p.155. Picture available at : Aristides de Sousa Mendes - Le juste de Bordeaux Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Homenagem Naçional, Cinema Tivoli, Avenida de Liberdade, Lisbon, Portugal, 23 March 1995.

- Sébastien (5 May 2007). "Aristides de Sousa Mendes". SebPhilately's About Stamps, Covers, News from the Philatelic World. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Mário Soares, "Encerramento da la parte por S. Exa o Presidente da República", Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Homenagem Nacional, Cinema Tivoli, Avenida de Liberdade, Lisbon, Portugal, 23 March 1995, as cited in Sebastian Mendes, "Lifelong Champion of Major Holocaust Hero Dies," International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, 17 December 2006. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Sebastian Mendes, "Lifelong Champion of Major Holocaust Hero Dies," International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, 17 December 2006. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- Christian House, "Sousa Mendes Saved More Lives Than Schindler So Why Isn't He a Household Name Too?" The Independent (London), 17 October 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Fundaçao Aristides de Sousa Mendes Archived 2012-03-17 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Mark Fonseca Rendeiro, "The Bravery of a Portuguese War Hero Resonates Today," The Guardian, 29 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "International Acknowledgment of Sousa Mendes on the 50th Anniversary of His Death", The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, 2004. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Salazar vence concurso 'Os Grandes Portugueses'". Jornalismo Porto Net. 26 March 2007. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Hatton, Barry (28 February 2008). "Portugal Honors Diplomat Who Saved Jews". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Casa do Passal," Archived 2014-03-10 at the Wayback Machine International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Petition: Aristides de Sousa Mendes’ name proposed for Bordeaux’ new bridge – France," Portuguese American Journal, 25 May 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "United Nations to Screen ‘The Rescuers’ to Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day While Honouring Heroic Actions, Moral Courage of 12 Diplomats," United Nations, New York, 8 January 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Casa do Passal". Casa do Passal. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- "Eric Moed". Eric Moed. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- Alexandre Soares, "A lista de Sousa Mendes," Visão, 13 June 2013, cover story. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Raphael Minder, "In Portugal, a Protector of a People is Honored," The New York Times, 9 July 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Community: City of Toronto to Honor Aristides de Sousa Mendes – Canada", Portuguese American Journal, 18 October 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Windavia Fleet Details," AirFleets.net. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Carta de Sousa Mendes chega ao Papa 67 anos depois," Archived 2013-12-17 at the Wayback Machine Boas Notícias, 5 December 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Obras na casa de Aristides de Sousa Mendes arrancam na última semana do mês" [Works on Sousa Mendes` house will start by the end of the month]. Público (in Portuguese). 15 May 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "Honored: TAP Air Portugal names aircraft after Aristides de Sousa Mendes – Portugal". Portuguese American Journal. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "Circular 14: The Apotheosis of Aristides An Oratorio Sousa Mendes Foundation". sousamendesfoundation.org. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- Fralon, p.88 and "Bromberger," Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Hahn," Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Fralon, p.88 and "Lissy Jarvik" Archived 2014-03-08 at the Wayback Machine and "Feingold," Archived 2014-11-06 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Ben Fulton, "U. Prof Meets Kin of Man Who Saved His Family From Nazis," The Salt Lake Tribune, 3 July 2010, retrieved 16 March 2014 and "Matuzewitz/Sternberg," Archived 2013-12-07 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "De Beauvoir," Archived 2014-03-15 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Afonso, Um Homem Bom, p.78 and "Dali," Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Afonso, Um Homem Bom, p.166 and "Blauschild," Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Dembitzer," Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Eisler," Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Fitelberg/Reicher," Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Frank/Lovett," Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Cornu/Gallimard," Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Afonso, Um Homem Bom, p.206 and "Malcuzynski," Archived 2014-03-15 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Grab," Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Afonso, Um Homem Bom, p.132 and "Haas," Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Abramowicz-Schimmel," Archived 2013-12-04 at the Wayback Machine Sousa Mendes Foundation. Retrieved 15 March 2014.