Assam Movement

The Assam Movement (also Anti-Foreigners Agitation) (1979–1985) was a popular uprising in Assam, India, that demanded the Government of India to detect, disenfranchise and deport illegal aliens.[4][2] Led by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) the movement defined a six-year period of sustained civil disobedience campaigns, political instability and widespread ethnic violence (Nellie massacre, 1983).[5] The movement ended in 1985 with the Assam Accord.[6][7]

| Assam agitation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A Students Rally during the Assam Movement | |||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Improper inclusion of foreign nationals in electoral rolls[1] | ||

| Methods | Demonstrations, civil disobedience, rioting, lynching | ||

| Concessions | Passage of the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Assam |

|---|

|

| Categories |

|

It was known since 1963 that foreign nationals had been improperly added to electoral rolls[8]—and when the draft enrollments in Mangaldoi showed high number of non-citizens in 1979[9] AASU decided to campaign for thoroughly revised electoral rolls in the entire state of Assam by boycotting the 1980 Lok Sabha election.[1][10] The Government of the day could not accept the demands of the movement leaders since it came at considerable political costs[11] and the movement escalated to economic blockades, oppression and ethnic conflict.

Background

Political Demography of Assam

| Year | Population | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| (1947-1951) | 274,455 | Partition of Bengal |

| (1952-1958) | 212,545 | 1950 East Pakistan riots |

| (1964-1968) | 1,068,455 | 1964 East Pakistan riots |

| 1971 | 347,555 | Bangladesh Liberation War |

| Total | 1,903,010 | Overall all immigration due to communal disturbance |

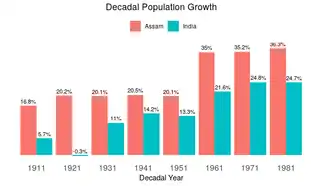

Assam, a Northeast Indian state, has been the fastest growing region in the Indian subcontinent for much of the 20th century with the population growing six-fold till the 1980s as against less than three-fold for India.[17] Since the natural growth rate of Assam has been found to be less than the national rate, the difference can only be attributed to a net immigration.[18]

Immigration in the 19th century was driven by British colonialism—tribal and low castes were brought in from central India to labour in tea gardens and educated Hindu Bengalis from Bengal to fill administrative and professional positions. The largest group, Muslims peasants from Mymensingh, immigrated after about 1901—and they settled in Goalpara in the first decade and further up the Brahmaputra valley in the next two decades. These major groups were joined by other smaller groups that settled as traders, merchants, bankers, moneylenders, and small industrialists.[12] Yet another community that had settled in Assam were Nepali dairy farmers.

The British dismantled the older Ahom system, made Bengali the official language (Assamese was restored in 1874), and placed Hindu Bengalis in colonial administrative positions. By 1891 one-fourth the population of Assam was of migrant origin. Assamese nationalism, which grew by the beginning of the 20th century, began to look at both the Hindu Bengalis as well as the British as alien rulers.[19] The emerging Assamese literate class aspired to the same positions as those enjoyed by the Bengali Hindus, mostly from Sylhet.

The Bengal Muslims, who came in mainly from Mymensingh, were cultivators who occupied flood plains and cleared forests,[20] and who were not in conflict with the Assamese and not aligned with the Bengali Hindus.[21] In fact the Assamese elite encouraged their settlement. In the post-partition period as Assamese nationalists tried to dismantle Bengali Hindu dominance from the colonial period the tea garden labourers as well as the Muslim Bengalis supported them.[22] Ever mindful of being the neighbour of the populous and culturally dominant Bengali people,[23] the Assamese were alarmed that immigration not only had continued illegally in the post-independence period but that illegal immigrants were being included in electoral rolls.[24]

Cross-border immigration

Immigration from East Bengal to Assam became cross-border in character following Partition of India—the 1951 census records 274,000 refugees between 1947 and 1951, most of who are estimated to be Hindu Bengalis. On the basis of natural growth rate, it was estimated that the immigrants numbered 221,000 between 1951 and 1961. In 1971, the surplus over the natural growth was 424,000 and the estimated illegal immigrants from 1971 to 1981 was 1.8 million.[25]

Immigration of Muslims from East Pakistan continued—though they declared India as the birth country and Assamese as their language, they recorded their religion correctly.[26] As the immigration issue was growing the immigrant Muslims from Bengal supported the Assamese—by accepting the Assamese language, supporting the official language act in contrast to the Bengali Hindus who opposed it, and casting their votes for the Congress.[27]

Foreign nationals in electoral rolls

In 1963 official reports emerged for the first time that foreigners were being enlisted in Indian voters list by politically interested parties.[8] In 1965 the Government of India directed the Assam Government to expel Pakistani (later Bangladesh) infiltrators but the implementation had to be given up when a number of Assam legislators threatened to resign.[28] In 1978 S L Shakdher (the then Chief Election Commissioner)[29] and a cabinet minister[30] admitted that the practice of enlisting foreigners in electoral rolls was going on.

AASU had included "expulsion of foreigners" in their charter demands and after Shakdher's announcement in 1978, called a three-day program of protest.[31]

Mangaldai Lok Sabha by-election, 1979

After the Lok Sabha member from the Mangaldoi Lok Sabha Constituency had died the Election Commission started the process for a by-election and published the draft electoral rolls and ordered a summary revision in April 1979.[32] It received a list of about 47,000 doubtful names of which about 36,000 were processed. Of these processed names 26,000 names (about 72 percent) were confirmed to be non-citizens.[33]

With the fall of two successive governments in Delhi—the Morarji Desai government in July 1979 and the subsequent Charan Singh government in August, 1979—early Lok Sabha elections were called and the Mangaldai by-election was cancelled.[34] Nevertheless, the large number of non-citizens in electoral rolls became a sensation and by October 1979 AASU decided to oppose the newly announced elections if the electoral rolls are not reviewed and the foreigners' names were not removed.[35]

Conflicts

AASU and AAGSP basic position

| A foreigner is a foreigner; a foreigner shall not be judged by the language he speaks or the religion he follows. Communal considerations (either religious or linguistic) cannot be taken into account while determining the citizenship of a person; the secular character of the Constitution does not allow that. (Emphasis in original, AASU and AAGSP 1980:6)[36] |

| Period | Demand |

|---|---|

| 1951– | Review legal status of all aliens |

| 1951–1961 | Identify, probably give citizenship |

| 1961–1971 | Distribute throughout India |

| 1971– | Deport |

Even though the relationship of the Assam Movement to the earlier Assamese Language Movement was clear[38] the leadership were careful to kept the issue of language out—instead they staked their claims purely on the basis of population statistics and constitutional rights and presented a set of demands that were secular and constitutionally legitimate.[39] They clearly defined who they considered to be foreigners and tried to project the problem as not local but constitutional.[36] Despite these formal positions and the demands structured around constitutional values, movement leaders did use ethnic themes for political mobilization.[40] The Assam Accord that concluded the Movement, in its Clause 6, called for protection of the "Assamese people".

The Government of India position

Indira Gandhi (Congress (I)) came to power after the 1980 Indian general election, and she met the Movement leaders in Delhi on 2 February 1980. She did not accept the demand to use the NRC 1951 and the Census report of 1952 as the basis for identifying foreigners and suggested 24 March 1971 as the cut-off date instead since she wanted to factor in the Liaquat–Nehru Pact of 8 April 1950 and her own agreement with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1972,[41] and the talks stalled.

Phased Developments

The duration of the Assam Movement could be divided into five phases.[42]

June 1979 to November 1980

AASU sponsored the first general strike on 8 June 1979 demanding the detection, disenfranchisement and deportation of foreigners.[43] This was followed by the formation of the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad, an ad hoc coalition of different political and cultural organizations, on 26 August 1979[44][45] On 27 November 1979, AASU-AAGSP called for the closure of all educational institutes and picketing in state and central government offices. Mass picketing was arranged in front of all polling offices where candidate filed their nominations, in the first week of December 1979. No candidates were allowed to file nomination papers in the Brahmaputra valley.

December 1980 to January 1983

On 10 December, the last date for submitting the nomination papers, was declared as a statewide bandh. The government proclaimed a curfew at different parts of the state, including the major city of Guwahati.

At Barpeta, then IGP K.P.S. Gill led the police force in escorting Bagam Abida Ahmed to file nomination papers; they attacked protestors. Khargeswar Talukdar, the 22-year-old general secretary of Barpeta AASU Unit, was beaten to death and thrown into a ditch next to the highway at Bhabanipur. Talukdar was honoured by the Assam Movement as its first Martyr.[46]

On 7 October 1982, while leading a procession from Nagaon to hojai in support of a bandh called by the All Assam Students Union, Anil Bora Was beaten to death at Hojai by people who opposed the bandh as well as the Movement.[47]

See also

- Assamese language movement

Notes

- "If there were a number of 'foreigners' in only one constituency—Mangaldai—what about other constituencies?...Naturally then, the next step for the AASU was to oppose the 1980 Lok Sabha elections without a thorough revision of electoral rolls of not just in Mangaldai but in the entire state...AASU leaders gave a call to political parties to boycott the polls till the EC revised the state's electoral rolls." (Pisharoty 2019:30)

- Baruah, Sanjib (1999). India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 116. ISBN 081223491X.

The citizenship status of many of the newer immigrants was ambiguous[...] The campaign also led to friction between the ethnic Assamese and some of Assam's "plains tribal" groups.

- "By September 1980 the immigrant organizations had become a third force in the negotiations on the Assam movement's demands. The government invited AAMSU leaders to Delhi for consultation during the negotiations between the government and the movement leaders." (Baruah 1986:1196)

- "[T]he movement leaders demanded that the central government take steps to identify, disenfranchise, and deport illegal aliens."(Baruah 1986:1184)

- "The years since 1979 saw governmental instability, sustained civil disobedience campaigns, and some of the worst ethnic violence in the history of post-independence India, including the killing of 3,000 people during the February 1983 election." (Baruah 1986:1184)

- (Baruah 1986)

- "Implementation of Assam Accord". assamaccord.assam.gov.in.

- "One of the first official admissions of this fact has been made in a publication of the Ministry of External Affairs as early as 1963. It is reported that 'enlistment of foreigners in the voters' lists has at times taken place at the instance of politically interested persons or parties." (Reddi 1981:30)

- (Pisharoty 2019:28)

- "Preparations to a bye election to the Mangaldoi parliamentary constituency in mid 1979 revealed that out of 47,000 alleged illegal entries of the names of foreigners brought to the notice of the electoral registration officers, 36,000 were disposed of and out of these as many as 26,000 or over 72 per cent were found to be and declared as illegal entries being those of non-citizens. What is true of the Mangaldoi constituency could be true of many other constituencies. No wonder, Mangaldoi became the rallying point of a renewed attack on the electoral rolls culminating in the boycott of the Lok Sabha poll in January 1980." (Reddi 1981:31)

- "To treat Hindu immigrants from East Pakistan and what subsequently became Bangladesh as illegal, irrespective of what the citizenship laws state, would have alienated significant sections of Hindu opinion in the country. On the other hand, to explicitly distinguish between Hindu "refugees" and Muslim "illegal aliens" would have cut into the secular fabric of the state and would have alienated India's Muslim minority. To expel "foreigners" would also have political costs internationally in terms of India's relations with Bangladesh: the official Bangladeshi position is that there are no illegal immigrants from Bangladesh in India." (Baruah 1986:1192f)

- (Weiner 1983:283)

- India (1951). "Annual Arrival of Refugees in Assam in 1946–1951". Census of India. XII, Part I (I-A): 353 – via web.archive.org.

- http://iussp2005.princeton.edu › ...PDF The Brahmaputra valley of India can be compared only with the Indus ...

- "iussp2005". iussp2005.princeton.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "Adelaide Research & Scholarship: Home". digital.library.adelaide.edu.au. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "Throughout this century Assam has been the fastest growing area in the subcontinent. Its population has grown nearly sixfold since 1901 when it had a population of 3.3 million; India's population has grown less than threefold over this period." (Weiner 1983:282)

- "Since there is no evidence that Assam's rate of increase was significantly different than that in the rest of India (in the 1970s its estimated rate of natural increase was actually slightly below the all-India average), the difference can only be accounted for by net immigration." (Weiner 1983:282)

- "By the beginning of the twentieth century Assamese nationalists were pitted against the Bengalis as well as against the British, both of whom were seen as alien rulers." (Weiner 1983:283)

- "Bengali Muslims reclaimed thousands of acres of land, cleared vast tracts of dense jungle along the south bank of the Brahmaputra, and occupied flooded lowlands all along the river. The largest single influx came from Mymensingh district, one of the most densely populated districts in East Bengal." (Weiner 1983:283)

- "In any event, there had been traditional enmity between Bengali Hindus and Bengali Muslims; the Bengali Muslims had much to gain and little to lose by siding with the Assamese." (Weiner 1983:285)

- "In this campaign to assert their culture and improve the employment opportunities of the Assamese middle classes, the Assamese won the support of two migrant communities, the tea plantation laborers from Bihar, and the Bengali Muslims." (Weiner 1983:284)

- "One should not underestimate the extent to which the peoples of the northeast, and especially the Assamese, have a sense that they are a small people living next to a vast Bengali population eager to burst out of a densely populated region. Bangladesh (in 1980) had a population of 88.5 million, West Bengal (in 1981) had 54.4 million, and Tripura 2 million, for a total of 145 million Bengalis, making them numerically second only to Hindi speakers in South Asia, and the third largest linguistic group in Asia." (Weiner 1983:287)

- " How many Bengalis entered and remained in Assam after the 1971 Pakistani civil war and the 1972 war between India and Pakistan is unknown. ... On the basis of these figures we can estimate that the immigration into Assam from 1971 to 1981 was on the order of 1.8 million. How much of this was migration from elsewhere in India and how much from Bangladesh is purely conjectural, although it is plausible to assume that most of it was illegal migration. The influx became politically alarming when the Election Commissioner in 1979 reported the unexpected large increase in the electoral rolls. To many Assamese it appeared as if the Bengali Hindus and Bengali Muslims together were now in a position to undermine Assamese rule." (Weiner 1983:286)

- (Weiner 1983:285–286)

- "Since immigration was no longer legal, recent Bengali Muslim migrants told census enumerators in 1961 that Assam was their place of birth and Assamese was their mother tongue. Bengali Muslims did, however, report their religion" (Weiner 1983:285)

- "In an effort to dissuade the Assamese from taking these steps, Bengali Muslims sided with the Assamese on issues that mattered to them, by declaring their mother tongue as Assamese, accepting the establishment of primary and secondary schools in Assamese, supporting the government against Bengali Hindus on the controversial issue of an official language for the state and for the university, and casting their votes for Congress.(Weiner 1983:285)

- "In 1965 when relations with Pakistan were deteriorating, the state government under instructions from New Delhi began expelling Pakistani "infiltrators."9 But the process had to be stopped when eleven members of the state Legislative Assembly protested that Indian Muslims were being harassed in the process, and threatened to resign." (Baruah 1986:1191)

- "On October 24–26, 1978 (t)he CEC declared "I would like to refer to the alarming situation in some states specially in North-Eastern region wherefrom disturbing reports are coming regarding large scale inclusion of foreign nationals in the electoral rolls." (Reddi 1981:31)

- "On November 27, 1978 a cabinet minister, while replying to a question in the Rajya Sabha, confirmed that 'large scale inclusion of foreign nationals in electoral rolls, specially in the North-Eastern region, has been taking place." (Reddi 1981:31)

- "On 28 October 1978, AASU registered its first reaction to Shakdher's comment by calling a three-day Satyagraha, including a dawn to dusk bandh in Guwahati demanding 'reservation of 80 percent jobs for locals'." (Pisharoty 2019:17)

- (Pisharoty 2019:24)

- "Preparations to a bye election to the Mangaldoi parliamentary constituency in mid 1979 revealed that out of 47,000 alleged illegal entries of the names of foreigners brought to the notice of the electoral registration officers, 36,000 were disposed of and out of these as many as 26,000 or over 72 per cent were found to be and declared as illegal entries being those of non-citizens." (Reddi 1981:31)

- (Pisharoty 2019:29)

- Iyer, Sukanya (14 August 2018). "Must Read: NRC For India— A Paradigm Shift from Vote Bank Politics to "India for Indians"". The Fearless Indian. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- (Kimura 2013:48)

- "AAGSP and AASU took the position that the government should review the legal status of all those who had entered the state after 1951. Bengalis and other non-Assamese would have to produce some evidence of their citizenship. Foreign nationals who had come between 1951 and 1961 should be screened and probably given citizenship. Those who came between 1961 and 1971 should be declared stateless and distributed throughout India. And those who had come after 1971 should be returned to Bangladesh." (Weiner 1983:289)

- "[T]here is a clear connection between the language movements of the 1960s and the 1970s and the antiforeigner movement." (Kimura 2013:49)

- (Kimura 2013:49)

- "Apart from Assamese cultural and historical symbols, the movement leaders drew on legal and constitutional arguments and symbols as well. Despite the presence of ethnic themes in the process of political mobilization, constitutional values significantly structured the demands of the movement." (Baruah 1986:1185)

- (Pisharoty 2019:47)

- "Five phases can be distinguished: (1) June 1979 to November 1980; (2) December 1980 to January 1983; (3) the election of February 1983; (4) March 1983 to May 1984; and (5) June 1984 to December 1985." (Baruah 1986:1193)

- "On June 8, 1979, the All Assam Students Union sponsored a 12-hour general strike (bandh) in the state to demand the "detection, disenfranchisement and deportation" of foreigners. That event turned out to be only the first of a protracted series of protest action." (Baruah 1986:1192)

- "On August 26, 1979, the AGSP was formed as an ad hoc coalition to coordinate a sustained statewide movement." (Baruah 1986:1192)

- "Among these were PLP, Assam Jatiyatabadi Dal (AJD), AJYCP, Assam Yuva Samaj, the Young Lawyers' Conference, Assam Sahitya Sabha, Karbi Parishad, Plain Tribes Council of Assam (Brahma) and All Assam Tribal Sangha. They were supported by the State Government Employees Federation besides various teachers' associations.(Pisharoty 2019:41–42)

- Kalita, Kangkan (1 February 2019). "Kin of 76 killed in Assam stir return awards". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- "Tale of two villages & their martyr duo". telegraphindia.com.

- "Tiwas' role in Nellie neglected: Author - 30 years after massacre, writer wants better understanding among communities". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- "...the majority of the participants were rural peasants belonging to mainstream communities, or from the lower strata of the caste system categorized as Scheduled Castes or Other Backward Classes." (Kimura 2013, p. 5)

References

- Baruah, Sanjib (1999). India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 116. ISBN 081223491X.

- Baruah, Sanjib (1986). "Immigration, Ethnic Conflict, and Political Turmoil—Assam, 1979–1985". Asian Survey. 26 (11): 1184–1206. doi:10.2307/2644315. JSTOR 2644315.

- Kimura, Makiko (2013). The Nellie Massacre of 1983: Agency of Rioters. Sage Publications India. ISBN 9788132111665.

- Pisharoty, Sangeeta Barooah (2019). Assam: the Accord, the Discord. Gurgaon: Penguin Random House.

- Reddi, P.S. (1981). "Electoral Rolls with special reference to Assam". The Indian Journal of Political Science. Indian Political Science Association. 42 (1): 27–37. JSTOR 41855074.

- Weiner, Myron (1983). "The Political Demography of Assam's Anti-Immigrant Movement". Population and Development Review. Population Council. 9 (2): 279–292. doi:10.2307/1973053. JSTOR 1973053.