Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) since the 1950s. The bomber is capable of carrying up to 70,000 pounds (32,000 kg) of weapons,[2] and has a typical combat range of around 8,800 miles (14,080 km) without aerial refueling.[3]

| B-52 Stratofortress | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A B-52H from Barksdale AFB flying over Texas | |

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| First flight | 15 April 1952 |

| Introduction | February 1955 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force NASA |

| Produced | 1952–1962 |

| Number built | 744[1] |

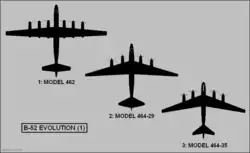

Beginning with the successful contract bid in June 1946, the B-52 design evolved from a straight wing aircraft powered by six turboprop engines to the final prototype YB-52 with eight turbojet engines and swept wings. The B-52 took its maiden flight in April 1952. Built to carry nuclear weapons for Cold War-era deterrence missions, the B-52 Stratofortress replaced the Convair B-36 Peacemaker. A veteran of several wars, the B-52 has dropped only conventional munitions in combat. The B-52's official name Stratofortress is rarely used; informally, the aircraft has become commonly referred to as the BUFF (Big Ugly Fat Fucker/Fella).[4][5][6][Note 1]

The B-52 has been in service with the USAF since 1955. As of June 2019, there are 76 aircraft in inventory; 58 operated by active forces (2nd Bomb Wing and 5th Bomb Wing), 18 by reserve forces (307th Bomb Wing), and about 12 in long-term storage at the Davis-Monthan AFB Boneyard.[8][9][10][11][12] The bombers flew under the Strategic Air Command (SAC) until it was disestablished in 1992 and its aircraft absorbed into the Air Combat Command (ACC); in 2010, all B-52 Stratofortresses were transferred from the ACC to the new Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). Superior performance at high subsonic speeds and relatively low operating costs have kept them in service despite the advent of later, more advanced strategic bombers, including the Mach 2+ Convair B-58 Hustler, the canceled Mach 3 North American XB-70 Valkyrie, the variable-geometry Rockwell B-1 Lancer, and the stealth Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit. The B-52 completed 60 years of continuous service with its original operator in 2015. After being upgraded between 2013 and 2015, the last airplanes are expected to serve into the 2050s.

Development

Origins

On 23 November 1945, Air Materiel Command (AMC) issued desired performance characteristics for a new strategic bomber "capable of carrying out the strategic mission without dependence upon advanced and intermediate bases controlled by other countries".[14] The aircraft was to have a crew of five or more turret gunners, and a six-man relief crew. It was required to cruise at 300 mph (260 knots, 480 km/h) at 34,000 feet (10,400 m) with a combat radius of 5,000 miles (4,300 nautical miles, 8,000 km). The armament was to consist of an unspecified number of 20 mm cannon and 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) of bombs.[15] On 13 February 1946, the USAF issued bid invitations for these specifications, with Boeing, Consolidated Aircraft, and Glenn L. Martin Company submitting proposals.[15]

On 5 June 1946, Boeing's Model 462, a straight-wing aircraft powered by six Wright T35 turboprops with a gross weight of 360,000 pounds (160,000 kg) and a combat radius of 3,110 miles (2,700 nmi, 5,010 km), was declared the winner.[16] On 28 June 1946, Boeing was issued a letter of contract for US$1.7 million to build a full-scale mockup of the new XB-52 and do preliminary engineering and testing.[17] However, by October 1946, the USAF began to express concern about the sheer size of the new aircraft and its inability to meet the specified design requirements.[18] In response, Boeing produced the Model 464, a smaller four-engine version with a 230,000 pound (105,000 kg) gross weight, which was briefly deemed acceptable.[18][19]

Subsequently, in November 1946, the Deputy Chief of Air Staff for Research and Development, General Curtis LeMay, expressed the desire for a cruising speed of 400 miles per hour (345 kn, 645 km/h), to which Boeing responded with a 300,000 lb (136,000 kg) aircraft.[20] In December 1946, Boeing was asked to change their design to a four-engine bomber with a top speed of 400 miles per hour, range of 12,000 miles (10,000 nmi, 19,300 km), and the ability to carry a nuclear weapon; in total, the aircraft could weigh up to 480,000 pounds (220,000 kg).[21] Boeing responded with two models powered by T35 turboprops. The Model 464-16 was a "nuclear only" bomber with a 10,000 pound (4,500 kg) payload, while the Model 464-17 was a general purpose bomber with a 9,000 pound (4,000 kg) payload.[21] Due to the cost associated with purchasing two specialized aircraft, the USAF selected Model 464-17 with the understanding that it could be adapted for nuclear strikes.[22]

In June 1947, the military requirements were updated and the Model 464-17 met all of them except for the range.[23] It was becoming obvious to the USAF that, even with the updated performance, the XB-52 would be obsolete by the time it entered production and would offer little improvement over the Convair B-36 Peacemaker; as a result, the entire project was postponed for six months.[24] During this time, Boeing continued to perfect the design, which resulted in the Model 464-29 with a top speed of 455 miles per hour (395 kn, 730 km/h) and a 5,000-mile range.[25] In September 1947, the Heavy Bombardment Committee was convened to ascertain performance requirements for a nuclear bomber. Formalized on 8 December 1947, these requirements called for a top speed of 500 miles per hour (440 kn, 800 km/h) and an 8,000 mile (7,000 nmi, 13,000 km) range, far beyond the capabilities of the 464-29.[24][26]

The outright cancellation of the Boeing contract on 11 December 1947 was staved off by a plea from its president William McPherson Allen to the Secretary of the Air Force Stuart Symington.[27] Allen reasoned that the design was capable of being adapted to new aviation technology and more stringent requirements.[28] In January 1948, Boeing was instructed to thoroughly explore recent technological innovations, including aerial refueling and the flying wing.[29] Noting stability and control problems Northrop Corporation was experiencing with their YB-35 and YB-49 flying wing bombers, Boeing insisted on a conventional aircraft, and in April 1948 presented a US$30 million (US$338 million today[30]) proposal for design, construction, and testing of two Model 464-35 prototypes.[31] Further revisions during 1948 resulted in an aircraft with a top speed of 513 miles per hour (445 kn, 825 km/h) at 35,000 feet (10,700 m), a range of 6,909 miles (6,005 nmi, 11,125 km), and a 280,000 pounds (125,000 kg) gross weight, which included 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) of bombs and 19,875 US gallons (75,225 L) of fuel.[32][33]

Design effort

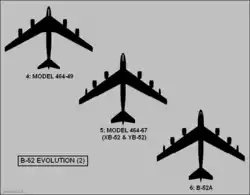

In May 1948, AMC asked Boeing to incorporate the previously discarded jet engine, with improvements in fuel efficiency, into the design.[34] That resulted in the development of yet another revision—in July 1948, Model 464-40 substituted Westinghouse J40 turbojets for the turboprops.[35] The USAF project officer who reviewed the Model 464-40 was favorably impressed, especially since he had already been thinking along similar lines. Nevertheless, the government was concerned about the high fuel consumption rate of the jet engines of the day, and directed that Boeing still use the turboprop-powered Model 464-35 as the basis for the XB-52. Although he agreed that turbojet propulsion was the future, General Howard A. Craig, Deputy Chief of Staff for Materiel, was not very enthusiastic about a jet-powered B-52, since he felt that the jet engine had not yet progressed sufficiently to permit skipping an intermediate turboprop stage. However, Boeing was encouraged to continue turbojet studies even without any expected commitment to jet propulsion.[36][37]

On Thursday, 21 October 1948, Boeing engineers George S. Schairer, Art Carlsen, and Vaughn Blumenthal presented the design of a four-engine turboprop bomber to the chief of bomber development, Colonel Pete Warden. Warden was disappointed by the projected aircraft and asked if the Boeing team could come up with a proposal for a four-engine turbojet bomber. Joined by Ed Wells, Boeing vice president of engineering, the engineers worked that night in The Hotel Van Cleve in Dayton, Ohio, redesigning Boeing's proposal as a four-engine turbojet bomber. On Friday, Colonel Warden looked over the information and asked for a better design. Returning to the hotel, the Boeing team was joined by Bob Withington and Maynard Pennell, two top Boeing engineers who were in town on other business.[38]

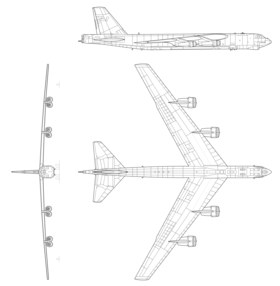

By late Friday night, they had laid out what was essentially a new airplane. The new design (464-49) built upon the basic layout of the B-47 Stratojet with 35-degree swept wings, eight engines paired in four underwings pods, and bicycle landing gear with wingtip outrigger wheels.[39] A notable feature of the landing gear was the ability to pivot both fore and aft main landing gear up to 20° from the aircraft centerline to increase safety during crosswind landings (allowing the aircraft to "crab" or roll with a sideways slip angle down the runway).[40] After a trip to a hobby shop for supplies, Schairer set to work building a model. The rest of the team focused on weight and performance data. Wells, who was also a skilled artist, completed the aircraft drawings. On Sunday, a stenographer was hired to type a clean copy of the proposal. On Monday, Schairer presented Colonel Warden with a neatly bound 33-page proposal and a 14-inch (36 cm) scale model.[38] The aircraft was projected to exceed all design specifications.[41]

Although the full-size mock-up inspection in April 1949 was generally favorable, range again became a concern since the J40s and early model J57s had excessive fuel consumption.[42] Despite talk of another revision of specifications or even a full design competition among aircraft manufacturers, General LeMay, now in charge of Strategic Air Command, insisted that performance should not be compromised due to delays in engine development.[43][44] In a final attempt to increase range, Boeing created the larger 464-67, stating that once in production, the range could be further increased in subsequent modifications.[45] Following several direct interventions by LeMay,[46] Boeing was awarded a production contract for thirteen B-52As and seventeen detachable reconnaissance pods on 14 February 1951.[47] The last major design change—also at General LeMay's insistence—was a switch from the B-47 style tandem seating to a more conventional side-by-side cockpit, which increased the effectiveness of the copilot and reduced crew fatigue.[48] Both XB-52 prototypes featured the original tandem seating arrangement with a framed bubble-type canopy (see above images).[49]

Tex Johnston noted, "The B-52, like the B-47, utilized a flexible wing. I saw the wingtip of the B-52 static test airplane travel 32 feet (9.8 m), from the negative 1-G load position to the positive 4-G load position." The flexible structure allowed "...the wing to flex during gust and maneuvering loads, thus relieving high-stress areas and providing a smoother ride." During a 3.5-G pullup, "The wingtips appeared about 35 degrees above level flight position."[50]

Pre-production and production

.jpg.webp)

During ground testing on 29 November 1951, the XB-52's pneumatic system failed during a full-pressure test; the resulting explosion severely damaged the trailing edge of the wing, necessitating considerable repairs. The YB-52, the second XB-52 modified with more operational equipment, first flew on 15 April 1952 with "Tex" Johnston as pilot.[51][52] A 2-hour, 21-minute proving flight from Boeing Field, King County, in Seattle, Washington, to Larson Air Force Base was undertaken with Boeing test pilot Johnston and USAF Lieutenant Colonel Guy M. Townsend.[53] The XB-52 followed on 2 October 1952.[54] The thorough development,[Note 2] including 670 days in the wind tunnel and 130 days of aerodynamic and aeroelastic testing, paid off with smooth flight testing. Encouraged, the USAF increased its order to 282 B-52s.[56]

| Fiscal year |

B-52 model | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A [57] |

B [58] |

C [59] |

D [60] |

E [61] |

F [62] |

G [63] |

H [64] |

Annual | Cumulative | |

| 1954 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||

| 1955 | 13 | 13 | 16 | |||||||

| 1956 | 35 | 5 | 1 | 41 | 57 | |||||

| 1957 | 2 | 30 | 92 | 124 | 181 | |||||

| 1958 | 77 | 100 | 10 | 187 | 368 | |||||

| 1959 | 79 | 50 | 129 | 497 | ||||||

| 1960 | 106 | 106 | 603 | |||||||

| 1961 | 37 | 20 | 57 | 660 | ||||||

| 1962 | 68 | 68 | 728 | |||||||

| 1963 | 14 | 14 | 742 | |||||||

| Total | 3 | 50 | 35 | 170 | 100 | 89 | 193 | 102 | 742 | 742 |

Only three of the 13 B-52As ordered were built.[65] All were returned to Boeing, and used in their test program.[57] On 9 June 1952, the February 1951 contract was updated to order the aircraft under new specifications. The final 10, the first aircraft to enter active service, were completed as B-52Bs.[57] At the roll-out ceremony on 18 March 1954, Air Force Chief of Staff General Nathan Twining said:

The long rifle was the great weapon of its day. ... today this B-52 is the long rifle of the air age.[66][67]

The B-52B was followed by progressively improved bomber and reconnaissance variants, culminating in the B-52G and turbofan B-52H. To allow rapid delivery, production lines were set up both at its main Seattle factory and at Boeing's Wichita facility. More than 5,000 companies were involved in the huge production effort, with 41% of the airframe being built by subcontractors.[68] The prototypes and all B-52A, B and C models (90 aircraft)[69] were built at Seattle. Testing of aircraft built at Seattle caused problems due to jet noise, which led to the establishment of curfews for engine tests. Aircraft were ferried 150 miles (240 km) east on their maiden flights to Larson Air Force Base near Moses Lake, where they were fully tested.[70]

As production of the B-47 came to an end, the Wichita factory was phased in for B-52D production, with Seattle responsible for 101 D-models and Wichita 69.[71] Both plants continued to build the B-52E, with 42 built at Seattle and 58 at Wichita,[72] and the B-52F (44 from Seattle and 45 from Wichita).[73] For the B-52G, Boeing decided in 1957 to transfer all production to Wichita, which freed up Seattle for other tasks, in particular, the production of airliners.[74][75] Production ended in 1962 with the B-52H, with 742 aircraft built, plus the original two prototypes.[76]

Upgrades

A proposed variant of the B-52H was the EB-52H, which would have consisted of 16 modified and augmented B-52H airframes with additional electronic jamming capabilities.[77][78] This variant would have restored USAF airborne jamming capability that it lost on retiring the EF-111 Raven. The program was canceled in 2005 following the removal of funds for the stand-off jammer. The program was revived in 2007, and cut again in early 2009.[79]

In July 2013, the USAF began a fleet-wide technological upgrade of its B-52 bombers called Combat Network Communications Technology (CONECT) to modernize electronics, communications technology, computing, and avionics on the flight deck. CONECT upgrades include software and hardware such as new computer servers, modems, radios, data-links, receivers, and digital workstations for the crew. One update is the AN/ARC-210 Warrior beyond-line-of-sight software programmable radio able to transmit voice, data, and information in-flight between B-52s and ground command and control centers, allowing the transmission and reception of data with updated intelligence, mapping, and targeting information; previous in-flight target changes required copying down coordinates. The ARC-210 allows machine-to-machine transfer of data, useful on long-endurance missions where targets may have moved before the arrival of the B-52. The aircraft will be able to receive information through Link-16. CONECT upgrades will cost $1.1 billion overall and take several years. Funding has been secured for 30 B-52s; the USAF hopes for 10 CONECT upgrades per year, but the rate has yet to be decided.[80]

Weapons upgrades include the 1760 Internal Weapons Bay Upgrade (IWBU), which gives a 66 percent increase in weapons payload using a digital interface (MIL-STD-1760) and rotary launcher. IWBU is expected to cost roughly $313 million.[80] The 1760 IWBU will allow the B-52 to carry eight[81] JDAM 2000 lb bombs, AGM-158B JASSM-ER cruise missile and the ADM-160C MALD-J decoy missiles internally. All 1760 IWBUs should be operational by October 2017. Two bombers will have the ability to carry 40 weapons in place of the 36 that three B-52s can carry.[82] The 1760 IWBU allows precision-guided missiles or bombs to be deployed from inside the weapons bay; the previous aircraft carried these munitions externally on the wing hardpoints. This increases the number of guided weapons (Joint Direct Attack Munition or JDAM) a B-52 can carry and reduces the need for guided bombs to be carried on the wings. The first phase will allow a B-52 to carry twenty-four GBU-38 500-pound guided bombs or twenty GBU-31 2,000-pound bombs, with later phases accommodating the JASSM and MALD family of missiles.[83] In addition to carrying more smart bombs, moving them internally from the wings reduces drag and achieves a 15 percent reduction in fuel consumption.[84]

The US Air Force Research Lab is investigating defensive laser weapons for the B-52.[85]

The B-52 is due to receive a range of upgrades alongside a planned engine retrofit. These upgrades aim to modernise the sensors and displays of the B-52. They include the new APG-79B4 AESA radar, replacing older mechanically scanned arrays, the streamlining of the nose and deletion of blisters housing the forward-looking infrared/electro-optical viewing system. In October 2022 Boeing released new images of what the upgrade would look like.[86] The upgrades will also include improved communication systems, new pylons, new cockpit displays and the deletion of one crew station. The changes will likely be enough to warrant changing the designation of the B-52H to B-52J or B-52K.[87]

Design

Overview

The B-52 shared many technological similarities with the preceding B-47 Stratojet strategic bomber. The two aircraft used the same basic design, such as swept wings and podded jet engines,[88] and the cabin included the crew ejection systems.[89] On the B-52D, the pilots and electronic countermeasures (ECM) operator ejected upwards, while the lower deck crew ejected downwards; until the B-52G, the gunner had to jettison the tail gun to bail out.[90] The tail gunner in early model B-52s was located in the traditional location in the tail of the plane, with both visual and radar gun laying systems; in later models the gunner was moved to the front of the fuselage, with gun laying carried out by radar alone, much like the B-58 Hustler's tail gun system.[91]

Structural fatigue was accelerated by at least a factor of eight in a low-altitude flight profile over that of high-altitude flying, requiring costly repairs to extend service life. In the early 1960s, the three-phase High Stress program was launched to counter structural fatigue, enrolling aircraft at 2,000 flying hours.[92][93] Follow-up programs were conducted, such as a 2,000-hour service life extension to select airframes in 1966–1968, and the extensive Pacer Plank reskinning, completed in 1977.[75][94] The wet wing introduced on G and H models was even more susceptible to fatigue, experiencing 60% more stress during a flight than the old wing. The wings were modified by 1964 under ECP 1050.[95] This was followed by a fuselage skin and longeron replacement (ECP 1185) in 1966, and the B-52 Stability Augmentation and Flight Control program (ECP 1195) in 1967.[95] Fuel leaks due to deteriorating Marman clamps continued to plague all variants of the B-52. To this end, the aircraft were subjected to Blue Band (1957), Hard Shell (1958), and finally QuickClip (1958) programs. The latter fitted safety straps that prevented catastrophic loss of fuel in case of clamp failure.[96] The B-52's service ceiling is officially listed as 50,000 feet, but operational experience shows this is difficult to reach when fully laden with bombs. According to one source: "The optimal altitude for a combat mission was around 43,000 feet, because to exceed that height would rapidly degrade the plane's range."[97]

In September 2006, the B-52 became one of the first US military aircraft to fly using alternative fuel. It took off from Edwards Air Force Base with a 50/50 blend of Fischer–Tropsch process (FT) synthetic fuel and conventional JP-8 jet fuel, which burned in two of the eight engines.[99] On 15 December 2006, a B-52 took off from Edwards with the synthetic fuel powering all eight engines, the first time a USAF aircraft was entirely powered by the blend. The seven-hour flight was considered a success.[99] This program is part of the Department of Defense Assured Fuel Initiative, which aimed to reduce crude oil usage and obtain half of its aviation fuel from alternative sources by 2016.[99] On 8 August 2007, Air Force Secretary Michael Wynne certified the B-52H as fully approved to use the FT blend.[100]

Flight controls

Because of the B-52's mission parameters, only modest maneuvers would be required with no need for spin recovery.[101] The aircraft has a relatively small, narrow chord rudder, giving it limited yaw control authority. Originally an all-moving vertical stabilizer was to be used, but was abandoned because of doubts about hydraulic actuator reliability.[101] Because the aircraft has eight engines, asymmetrical thrust due to the loss of an engine in flight would be minimal and correctable with the narrow rudder. To assist with crosswind takeoffs and landings the main landing gear can be pivoted 20 degrees to either side from neutral.[102] This yaw adjustable crosswind landing gear would be preset by the crew according to wind observations made on the ground.

The elevator is also very narrow in chord like the rudder, and the B-52 suffers from limited elevator control authority. For long term pitch trim and airspeed changes the aircraft uses an all-moving tail with the elevator used for small adjustments within a stabilizer setting. The stabilizer is adjustable through 13 degrees of movement (nine up, four down) and is crucial to operations during takeoff and landing due to large pitch changes induced by flap application.[103]

B-52s prior to the G models had very small ailerons with a short span that was approximately equal to their chord. These "feeler ailerons" were used to provide feedback forces to the pilot's control yoke and to fine tune the roll axes during delicate maneuvers such as aerial refueling.[101] Due to twisting of the thin main wing, conventional outboard flap type ailerons would lose authority and therefore could not be used. In other words, aileron activation would cause the wing to twist, undermining roll control. Six spoilerons on each wing are responsible for the majority of roll control. The late B-52G models eliminated the ailerons altogether and added an extra spoileron to each wing.[101] Partly because of the lack of ailerons, the B-52G and H models were more susceptible to Dutch roll.[103]

Avionics

Ongoing problems with avionics systems were addressed in the Jolly Well program, completed in 1964, which improved components of the AN/ASQ-38 bombing navigational computer and the terrain computer. The MADREC (Malfunction Detection and Recording) upgrade fitted to most aircraft by 1965 could detect failures in avionics and weapons computer systems, and was essential in monitoring the AGM-28 Hound Dog missiles. The electronic countermeasures capability of the B-52 was expanded with Rivet Rambler (1971) and Rivet Ace (1973).[104]

To improve operations at low altitude, the AN/ASQ-151 Electro-Optical Viewing System (EVS), which consisted of a low light level television (LLLTV) and a forward looking infrared (FLIR) system mounted in blisters under the noses of B-52Gs and Hs between 1972 and 1976.[105] The navigational capabilities of the B-52 were later augmented with the addition of GPS in the 1980s.[106] The IBM AP-101, also used on the Rockwell B-1 Lancer bomber and the Space Shuttle, was the B-52's main computer.[107]

In 2007, the LITENING targeting pod was fitted, which increased the effectiveness of the aircraft in the attack of ground targets with a variety of standoff weapons, using laser guidance, a high-resolution forward-looking infrared sensor (FLIR), and a CCD camera used to obtain target imagery.[108] LITENING pods have been fitted to a wide variety of other US aircraft, such as the McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon and the McDonnell Douglas AV-8B Harrier II.[109]

Armament

The ability to carry up to 20 AGM-69 SRAM nuclear missiles was added to G and H models, starting in 1971.[110] To further improve its offensive ability, air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) were fitted.[111] After testing of both the USAF-backed Boeing AGM-86 and the Navy-backed General Dynamics AGM-109 Tomahawk, the AGM-86B was selected for operation by the B-52 (and ultimately by the B-1 Lancer).[112] A total of 194 B-52Gs and Hs were modified to carry AGM-86s, carrying 12 missiles on underwing pylons, with 82 B-52Hs further modified to carry another eight missiles on a rotary launcher fitted in the bomb-bay. To conform with SALT II Treaty requirements that cruise missile-capable aircraft be readily identifiable by reconnaissance satellites, the cruise missile armed B-52Gs were modified with a distinctive wing root fairing. As all B-52Hs were assumed modified, no visual modification of these aircraft was required.[113] In 1990, the stealthy AGM-129 ACM cruise missile entered service; although intended to replace the AGM-86, a high cost and the Cold War's end led to only 450 being produced; unlike the AGM-86, no conventional, non-nuclear version was built.[114] The B-52 was to have been modified to utilize Northrop Grumman's AGM-137 TSSAM weapon; however, the missile was canceled due to development costs.[115]

_and_GAM-72_Quail_decoy_missile_and_trailer_061127-F-1234S-010.jpg.webp)

Those B-52Gs not converted as cruise missile carriers underwent a series of modifications to improve conventional bombing. They were fitted with a new Integrated Conventional Stores Management System (ICSMS) and new underwing pylons that could hold larger bombs or other stores than could the external pylons. Thirty B-52Gs were further modified to carry up to 12 AGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles each, while 12 B-52Gs were fitted to carry the AGM-142 Have Nap stand-off air-to-ground missile.[116] When the B-52G was retired in 1994, an urgent scheme was launched to restore an interim Harpoon and Have Nap capability,[Note 3] the four aircraft being modified to carry Harpoon and four to carry Have Nap under the Rapid Eight program.[119]

The Conventional Enhancement Modification (CEM) program gave the B-52H a more comprehensive conventional weapons capability, adding the modified underwing weapon pylons used by conventional-armed B-52Gs, Harpoon and Have Nap, and the capability to carry new-generation weapons including the Joint Direct Attack Munition and Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser guided bombs, the AGM-154 glide bomb and the AGM-158 JASSM missile. The CEM program also introduced new radios, integrated Global Positioning System into the aircraft's navigation system and replaced the under-nose FLIR with a more modern unit. Forty-seven B-52Hs were modified under the CEM program by 1996, with 19 more by the end of 1999.[120][121]

By around 2010, U.S. Strategic Command stopped assigning B61 and B83 nuclear gravity bombs to B-52, and later listed only the B-2 as tasked with delivering strategic nuclear bombs in budget requests. Nuclear gravity bombs were removed from the B-52's capabilities because it is no longer considered survivable enough to penetrate modern air defenses, instead relying on nuclear cruise missiles and focusing on expanding its conventional strike role.[122] The 2019 "Safety Rules for U.S. Strategic Bomber Aircraft" manual subsequently confirmed the removal of B61-7 and B83-1 gravity bombs from the B-52H's approved weapons configuration.[123]

Starting in 2016, Boeing is to upgrade the internal rotary launchers to the MIL-STD-1760 interface to enable the internal carriage of smart bombs, which previously could be carried only on the wings.[124]

While the B-1 Lancer has a larger theoretical maximum payload of 75,000 lb compared to the B-52's 70,000 lb, the bombers are rarely able to carry their full loads. The most the B-52 carries is a full load of AGM-86Bs totaling 62,660 lb. The B-1 has the internal weapons bay space to carry more GBU-31 JDAMs and JASSMs, but the B-52 upgraded with the conventional rotary launcher can carry more of other JDAM variants.[125]

AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response (ARRW) hypersonic missile and the future Long Range Stand Off (LRSO) nuclear-armed air-launched cruise missile will join the B-52 inventory in the future.[126]

Engines

The eight engines of the B-52 are paired in pods and suspended by four pylons beneath and forward of the wings' leading edge. The careful arrangement of the pylons also allowed them to work as wing fences and delay the onset of stall. The first two prototypes, XB-52 and YB-52, were both powered by experimental Pratt & Whitney YJ57-P-3 turbojet engines of 8,700 pounds-force (39 kN) of static thrust each.[103]

The B-52A models were equipped with Pratt & Whitney J57-P-1W turbojets, providing a dry thrust of 10,000 pounds-force (44 kN) which could be increased for short periods to 11,000 pounds-force (49 kN) with water injection. The water was carried in a 360 US gallons (1,400 l) tank in the rear fuselage.

B-52B, C, D and E models were equipped with Pratt & Whitney J57-P-29W, J57-P-29WA, or J57-P-19W series engines all rated at 10,500 lbf (47 kN). The B-52F and G models were powered by Pratt & Whitney J57-P-43WB turbojets, each rated at 13,750 pounds-force (61.2 kN) static thrust with water injection.

On 9 May 1961, the B-52H began to be delivered to the USAF with cleaner burning and quieter Pratt & Whitney TF33-P-3 turbofans with a maximum thrust of 17,100 pounds-force (76 kN).[103]

Engine retrofit

In a study for the USAF in the mid-1970s, Boeing investigated replacing the engines, changing to a new wing, and other improvements to upgrade B-52G/H aircraft as an alternative to the B-1A, then in development.[127]

In 1996, Rolls-Royce and Boeing jointly proposed fitting each B-52 with four leased Rolls-Royce RB211-535 engines. This would have involved replacing the eight Pratt & Whitney TF33 engines (total thrust 136,000 lbf (600 kN)) with four RB211 engines (total thrust 148,000 lbf (660 kN)), which would increase range and reduce fuel consumption, at a cost of approximately US$2.56 billion for the whole fleet. However, a USAF analysis in 1997 concluded that Boeing's estimated savings of US$4.7 billion would not be realized and that re-engining would instead cost US$1.3 billion more than keeping the existing engines, citing significant up-front procurement and re-tooling expenditure.[128]

The USAF's 1997 rejection of re-engining was subsequently disputed in a Defense Science Board (DSB) report in 2003. The DSB urged the USAF to re-engine the aircraft without delay,[129] saying doing so would not only create significant cost savings, but reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase aircraft range and endurance; these conclusions were in line with the conclusions of a separate Congress-funded study conducted in 2003. Criticizing the USAF cost analysis, the DSB found that among other things, the USAF failed to account for the cost of aerial refueling; the DSB estimated that aerial refueling cost $17.50 per US gallon ($4.62/l), whereas the USAF had failed to account for the cost of delivering the fuel and so had only priced fuel at $1.20 per US gallon ($0.32/l).[130]

On 23 April 2020, the USAF released its request for proposals for 608 commercial engines plus spares and support equipment, with the plan to award the contract in May 2021.[131] This Commercial Engine Re-engining Program (CERP) saw General Electric propose its CF34-10 and Passport turbofans, Pratt & Whitney its PW800, and Rolls Royce its F130.[131] On 24 September 2021, the USAF selected the Rolls-Royce F130 as the winner, and announced plans to purchase 650 engines (608 direct replacements and 42 spares), for $2.6 billion.[132]

Unlike the previous re-engine proposal which also involved reducing the number of engines from eight to four, the F130 re-engine program maintains eight engines on the B-52. Although four-engine operation would be more efficient, retrofitting the airframe to operate with only four engines would involve additional changes to the aircraft's systems and control surfaces (particularly the rudder), thereby increasing the time, cost and complexity of the project.[133]

Costs

| Inflation year |

X/YB-52 | B-52A | B-52B | B-52C | B-52D | B-52E | B-52F | B-52G | B-52H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit R&D cost | 1955 | 100 M | ||||||||

| Current | 1,012 M | |||||||||

| Airframe | 1955 | 26.433 M | 11.328 M | 5.359 M | 4.654 M | 3.700 M | 3.772 M | 5.352 M | 6.076 M | |

| Engines | 1955 | 2.848 M | 2.547 M | 1.513 M | 1.291 M | 1.257 M | 1.787 M | 1.428 M | 1.640 M | |

| Electronics | 1955 | 50,761 | 61,198 | 71,397 | 68,613 | 54,933 | 60,111 | 66,374 | 61,020 | |

| Armament and ordnance | 1955 | 57,067 | 494 K | 304 K | 566 K | 936 K | 866 K | 847 K | 1.508 M | |

| Current | 577,263 | 5 M | 3.08 M | 5.728 M | 9.47 M | 8.76 M | 8.57 M | 15.3 M | ||

| Flyaway cost | 1955 | 28.38 M | 14.43 M | 7.24 M | 6.58 M | 5.94 M | 6.48 M | 7.69 M | 9.29 M | |

| Current | 287.1 M | 146 M | 73.2 M | 66.6 M | 60.1 M | 66.6 M | 77.8 M | 94 M | ||

| Maintenance cost per flying hour |

1955 | 925 | 1,025 | 1,025 | 1,182 | |||||

| Current | 9,357 | 10,368 | 10,368 | 11,957 | ||||||

| Note: The original costs were in approximate 1955 United States dollars.[134] Figures in tables noted with current have been adjusted for inflation to the current calendar year.[30] | ||||||||||

Operational history

Introduction

Although the B-52A was the first production variant, these aircraft were used only in testing. The first operational version was the B-52B that had been developed in parallel with the prototypes since 1951. First flying in December 1954, B-52B, AF Serial Number 52-8711, entered operational service with 93rd Heavy Bombardment Wing (93rd BW) at Castle Air Force Base, California, on 29 June 1955. The wing became operational on 12 March 1956. The training for B-52 crews consisted of five weeks of ground school and four weeks of flying, accumulating 35 to 50 hours in the air. The new B-52Bs replaced operational B-36s on a one-to-one basis.[135]

Early operations were problematic;[136] in addition to supply problems, there were also technical issues.[137] Ramps and taxiways deteriorated under the aircraft's weight, the fuel system was prone to leaks and icing,[138] and bombing and fire control computers were unreliable.[137] The split level cockpit presented a temperature control problem – the pilots' cockpit was heated by sunlight while the observer and the navigator on the bottom deck sat on the ice-cold floor. Thus, a comfortable temperature setting for the pilots caused the other crew members to freeze, while a comfortable temperature for the bottom crew caused the pilots to overheat.[139] The J57 engines proved unreliable. Alternator failure caused the first fatal B-52 crash in February 1956;[140] as a result, the fleet was briefly grounded. In July, fuel and hydraulic issues grounded the B-52s again. In response to maintenance issues, the USAF set up "Sky Speed" teams of 50 contractors at each B-52 base to perform maintenance and routine checkups, taking an average of one week per aircraft.[141]

On 21 May 1956, a B-52B (52-13) dropped a Mk-15 nuclear bomb over the Bikini Atoll in a test code-named Cherokee. It was the first air-dropped thermonuclear weapon.[142] This aircraft now is on display at the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque, NM. From 24 to 25 November 1956, four B-52Bs of the 93rd BW and four B-52Cs of the 42nd BW flew nonstop around the perimeter of North America in Operation Quick Kick, which covered 15,530 miles (13,500 nmi, 25,000 km) in 31 hours, 30 minutes. SAC noted the flight time could have been reduced by 5 to 6 hours had the four inflight refuelings been done by fast jet-powered tanker aircraft rather than propeller-driven Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighters.[143] In a demonstration of the B-52's global reach, from 16 to 18 January 1957, three B-52Bs made a non-stop flight around the world during Operation Power Flite, during which 24,325 miles (21,145 nmi, 39,165 km) was covered in 45 hours 19 minutes (536.8 mph or 863.9 km/h) with several in-flight refuelings by KC-97s.[144][Note 4]

The B-52 set many records over the next few years. On 26 September 1958, a B-52D set a world speed record of 560.705 miles per hour (487 kn, 902 km/h) over a 10,000 kilometers (5,400 nmi, 6,210 mi) closed circuit without a payload. The same day, another B-52D established a world speed record of 597.675 miles per hour (519 kn, 962 km/h) over a 5,000 kilometer (2,700 nmi, 3,105 mi) closed circuit without a payload.[94] On 14 December 1960, a B-52G set a world distance record by flying unrefueled for 10,078.84 miles (8,762 nmi, 16,227 km); the flight lasted 19 hours 44 minutes (510.75 mph or 821.97 km/h).[145] From 10 to 11 January 1962, a B-52H (60-40) set a world distance record by flying unrefueled, surpassing the prior B-52 record set two years earlier, from Kadena Air Base, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, to Torrejón Air Base, Spain, which covered 12,532.28 miles (10,895 nmi, 20,177 km).[64][146] The flight passed over Seattle, Fort Worth and the Azores.

Cold War

When the B-52 entered into service, the Strategic Air Command (SAC) intended to use it to deter and counteract the vast and modernizing Soviet Union's military. As the Soviet Union increased its nuclear capabilities, destroying or "countering" the forces that would deliver nuclear strikes (bombers, missiles, etc.) became of great strategic importance.[147] The Eisenhower administration endorsed this switch in focus; the President in 1954 expressing a preference for military targets over civilian ones, a principle reinforced in the Single Integrated Operation Plan (SIOP), a plan of action in the case of nuclear war breaking out.[148]

Throughout the Cold War, B-52s and other US strategic bombers performed airborne alert patrols under code names such as Head Start, Chrome Dome, Hard Head, Round Robin and Giant Lance. Bombers loitered at high altitude near the borders of the Soviet Union to provide rapid first strike or retaliation capability in case of nuclear war.[149] These airborne patrols formed one component of the US's nuclear deterrent, which would act to prevent the breakout of a large-scale war between the US and the Soviet Union under the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction.[150]

Due to the late 1950s-era threat of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) that could threaten high-altitude aircraft,[151][152] seen in practice in the 1960 U-2 incident,[153] the intended use of B-52 was changed to serve as a low-level penetration bomber during a foreseen attack upon the Soviet Union, as terrain masking provided an effective method of avoiding radar and thus the threat of the SAMs.[154] The aircraft was planned to fly towards the target at 400–440 mph (640–710 km/h) and deliver their weapons from 400 ft (120 m) or lower.[155] Although never intended for the low level role, the B-52's flexibility allowed it to outlast several intended successors as the nature of aerial warfare changed. The B-52's large airframe enabled the addition of multiple design improvements, new equipment, and other adaptations over its service life.[104]

In November 1959, to improve the aircraft's combat capabilities in the changing strategic environment, SAC initiated the Big Four modification program (also known as Modification 1000) for all operational B-52s except early B models.[92][154] The program was completed by 1963.[156] The four modifications were the ability to launch AGM-28 Hound Dog standoff nuclear missiles and ADM-20 Quail decoys, an advanced electronic countermeasures (ECM) suite, and upgrades to perform the all-weather, low-altitude (below 500 feet or 150 m) interdiction mission in the face of advancing Soviet missile-based air defenses.[156]

In the 1960s, there were concerns over the fleet's capable lifespan. Several projects beyond the B-52, the Convair B-58 Hustler and North American XB-70 Valkyrie, had either been aborted or proved disappointing in light of changing requirements, which left the older B-52 as the main bomber as opposed to the planned successive aircraft models.[157][158] On 19 February 1965, General Curtis E. LeMay testified to Congress that the lack of a follow-up bomber project to the B-52 raised the danger that, "The B-52 is going to fall apart on us before we can get a replacement for it."[159] Other aircraft, such as the General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark, later complemented the B-52 in roles the aircraft was not as capable in, such as missions involving high-speed, low-level penetration dashes.[160]

Vietnam War

.jpg.webp)

With the escalating situation in Southeast Asia, 28 B-52Fs were fitted with external racks for 24 of the 750 lb (340 kg) bombs under project South Bay in June 1964; an additional 46 aircraft received similar modifications under project Sun Bath.[73] In March 1965, the United States commenced Operation Rolling Thunder. The first combat mission, Operation Arc Light, was flown by B-52Fs on 18 June 1965, when 30 bombers of the 9th and 441st Bombardment Squadrons struck a communist stronghold near the Bến Cát District in South Vietnam. The first wave of bombers arrived too early at a designated rendezvous point, and while maneuvering to maintain station, two B-52s collided, which resulted in the loss of both bombers and eight crewmen. The remaining bombers, minus one more that turned back due to mechanical problems, continued towards the target.[161] Twenty-seven Stratofortresses bombed a one-by-two-mile (1.6 by 3.2 km) target box from between 19,000 and 22,000 feet (5,800 and 6,700 m), with a little more than 50% of the bombs falling within the target zone.[162] The force returned to Andersen Air Force Base except for one bomber with electrical problems that recovered to Clark Air Base, the mission having lasted 13 hours. Post-strike assessment by teams of South Vietnamese troops with American advisors found evidence that the Viet Cong had departed from the area before the raid, and it was suspected that infiltration of the south's forces may have tipped off the north because of the South Vietnamese Army troops involved in the post-strike inspection.[163]

Beginning in late 1965, a number of B-52Ds underwent Big Belly modifications to increase bomb capacity for carpet bombings.[164] While the external payload remained at 24 of 500 lb (227 kg) or 750 lb (340 kg) bombs, the internal capacity increased from 27 to 84 for 500 lb bombs, or from 27 to 42 for 750 lb bombs.[165] The modification created enough capacity for a total of 60,000 lb (27,215 kg) using 108 bombs. Thus modified, B-52Ds could carry 22,000 lb (9,980 kg) more than B-52Fs.[166] Designed to replace B-52Fs, modified B-52Ds entered combat in April 1966 flying from Andersen Air Force Base, Guam. Each bombing mission lasted 10 to 12 hours and included an aerial refueling by KC-135 Stratotankers.[51] In spring 1967, B-52s began flying from U Tapao Airfield in Thailand so that refueling was not required.[165]

B-52s were employed during the Battle of Ia Drang in November 1965, notable as the aircraft's first use in a tactical support role.[167]

The B-52s were restricted to bombing suspected Communist bases in relatively uninhabited sections, because their potency approached that of a tactical nuclear weapon. A formation of six B-52s, dropping their bombs from 30,000 feet [9,000 m], could "take out"... almost everything within a "box" approximately five-eighths mile wide by two miles long [1 × 3.2 km]. Whenever Arc Light struck ... in the vicinity of Saigon, the city woke from the tremor..

Neil Sheehan, war correspondent, writing before the mass attacks on heavily populated cities including North Vietnam's capital.[168]

On 22 November 1972, a B-52D (55-110) from U-Tapao was hit by a SAM while on a raid over Vinh. The crew was forced to abandon the damaged aircraft over Thailand. This was the first B-52 destroyed by hostile fire.[169]

The zenith of B-52 attacks in Vietnam was Operation Linebacker II (sometimes referred to as the Christmas Bombing), conducted from 18 to 29 December 1972, which consisted of waves of B-52s (mostly D models, but some Gs without jamming equipment and with a smaller bomb load). Over 12 days, B-52s flew 729 sorties[170] and dropped 15,237 tons of bombs on Hanoi, Haiphong, and other targets.[106][171] Originally 42 B-52s were committed to the war; however, numbers were frequently twice this figure.[172] During Operation Linebacker II, fifteen B-52s were shot down, five were heavily damaged (one crashed in Laos), and five suffered medium damage. A total of 25 crewmen were killed in these losses.[173] North Vietnam claimed 34 B-52s were shot down.[174]

During the war 31 B-52s were lost, including 10 shot down over North Vietnam.[175]

Air-to-air combat

During the Vietnam War, B-52D tail gunners were credited with shooting down two MiG-21 "Fishbeds". On 18 December 1972 tail gunner Staff Sergeant Samuel O. Turner's B-52 had just completed a bomb run for Operation Linebacker II and was turning away, when a Vietnam People's Air Force (VPAF) MiG-21 approached.[176] The MiG and the B-52 locked onto each other. When the fighter drew within range, Turner fired his quad (four guns on one mounting) .50 (12.7 mm) caliber machine guns.[177] The MiG exploded aft of the bomber,[176] as confirmed by Master Sergeant Louis E. Le Blanc, the tail gunner in a nearby Stratofortress. Turner received a Silver Star for his actions.[178] His B-52, tail number 56-676, is preserved on display with air-to-air kill markings at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington.[176]

On 24 December 1972, during the same bombing campaign, the B-52 Diamond Lil was headed to bomb the Thái Nguyên railroad yards when tail gunner Airman First Class Albert E. Moore spotted a fast-approaching MiG-21.[179] Moore opened fire with his quad .50 (12.7 mm) caliber guns at 4,000 yd (3,700 m), and kept shooting until the fighter disappeared from his scope. Technical Sergeant Clarence W. Chute, a tail gunner aboard another Stratofortress, watched the MiG catch fire and fall away;[177] this was not confirmed by the VPAF.[180] Diamond Lil is preserved on display at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado.[179] Moore was the last bomber gunner believed to have shot down an enemy aircraft with machine guns in aerial combat.[177]

The two B-52 tail gunner kills were not confirmed by VPAF, and they admitted to the loss of only three MiGs, all by F-4s.[180] Vietnamese sources have attributed a third air-to-air victory to a B-52, a MiG-21 shot down on 16 April 1972.[181] These victories make the B-52 the largest aircraft credited with air-to-air kills.[Note 5] The last Arc Light mission without fighter escort took place on 15 August 1973, as U.S. military action in Southeast Asia was wound down.[182]

Post-Vietnam War service

B-52Bs reached the end of their structural service life by the mid-1960s and all were retired by June 1966, followed by the last of the B-52Cs on 29 September 1971; except for NASA's B-52B "008" which was eventually retired in 2004 at Edwards Air Force Base, California.[183] Another of the remaining B Models, "005" is on display at the Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum in Denver, Colorado.[184]

A few time-expired E models were retired in 1967 and 1968, but the bulk (82) were retired between May 1969 and March 1970. Most F models were also retired between 1967 and 1973, but 23 survived as trainers until late 1978. The fleet of D models served much longer; 80 D models were extensively overhauled under the Pacer Plank program during the mid-1970s.[185] Skinning on the lower wing and fuselage was replaced, and various structural components were renewed. The fleet of D models stayed largely intact until late 1978, when 37 not already upgraded Ds were retired.[186] The remainder were retired between 1982 and 1983.[187]

The remaining G and H models were used for nuclear standby ("alert") duty as part of the United States' nuclear triad, the combination of nuclear-armed land-based missiles, submarine-based missiles and manned bombers. The B-1, intended to supplant the B-52, replaced only the older models and the supersonic FB-111.[188] In 1991, B-52s ceased continuous 24-hour SAC alert duty.[189]

After Vietnam the experience of operations in a hostile air defense environment was taken into account. Due to this B-52s were modernized with new weapons, equipment and both offensive and defensive avionics. This and the use of low-level tactics marked a major shift in the B-52's utility. The upgrades were:

- Supersonic short-range nuclear missiles: G and H models were modified to carry up to 20 SRAM missiles replacing existing gravity bombs. Eight SRAMs were carried internally on a special rotary launcher and 12 SRAMs were mounted on two wing pylons. With SRAM, the B-52s could strike heavily defended targets without entering the terminal defenses.

- New countermeasures: Phase VI ECM modification was the sixth major ECM program for the B-52. It improved the aircraft's self-protection capability in the dense Soviet air defense environment. The new equipment expanded signal coverage, improved threat warning, provided new countermeasures techniques and increased the quantity of expendables. The power requirements of Phase VI ECM also consumed most of the excess electrical capacity on the B-52G.

- B-52G and Hs were also modified with electro-optical viewing system (EVS) that made low-level operations and terrain avoidance much easier and safer. EVS system contained a low light level television (LLTV) camera and a forward looking infrared (FLIR) camera to display information needed for penetration at lower altitude.

- Subsonic-cruise unarmed decoy: SCUD resembled the B-52 on radar. As an active decoy, it carried ECM and other devices, and it had a range of several hundred miles. Although SCUD was never deployed operationally, the concept was developed, becoming known as the air launched cruise missile (ALCM-A).

These modifications increased weight by nearly 24,000 lb (10,900 kg), and decreased operational range by 8–11%. This was considered acceptable for the increase in capabilities.[190]

After the fall of the Soviet Union, all B-52Gs remaining in service were destroyed in accordance with the terms of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). The Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Center (AMRC) cut the 365 B-52s into pieces. Completion of the destruction task was verified by Russia via satellite and first-person inspection at the AMARC facility.[191]

Gulf War and later

B-52 strikes were an important part of Operation Desert Storm. Starting on 16 January 1991, a flight of B-52Gs flew from Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, refueled in the air en route, struck targets in Iraq, and returned home — a journey of 35 hours and 14,000 miles (23,000 km) round trip. It set a record for longest-distance combat mission, breaking the record previously held by an RAF Vulcan bomber in 1982; however, this was achieved using forward refueling.[193][194] Those seven B-52s flew the first combat sorties of Operation Desert Storm, firing 35 AGM-86C CALCM standoff missiles and successfully destroying 85–95 percent of their targets.[195] B-52Gs operating from the King Abdullah Air Base at Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, RAF Fairford in the United Kingdom, Morón Air Base, Spain, and the island of Diego Garcia in the British Indian Ocean Territory flew bombing missions over Iraq, initially at low altitude. After the first three nights, the B-52s moved to high-altitude missions instead, which reduced their effectiveness and psychological impact compared to the low altitude role initially played.[196]

The conventional strikes were carried out by three bombers, which dropped up to 153 of the 750-pound M117 bomb over an area of 1.5 by 1 mi (2.4 by 1.6 km). The bombings demoralized the defending Iraqi troops, many of whom surrendered in the wake of the strikes.[197] In 1999, the science and technology magazine Popular Mechanics described the B-52's role in the conflict: "The Buff's value was made clear during the Gulf War and Desert Fox. The B-52 turned out the lights in Baghdad."[198] During Operation Desert Storm, B-52s flew about 1,620 sorties, and delivered 40% of the weapons dropped by coalition forces.[199]

During the conflict, several claims of Iraqi air-to-air successes were made, including an Iraqi pilot, Khudai Hijab, who allegedly fired a Vympel R-27R missile from his MiG-29 and damaged a B-52G on the opening night of the Gulf War.[200] However, the USAF disputes this claim, stating the bomber was actually hit by friendly fire, an AGM-88 High-speed, Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) that homed on the fire-control radar of the B-52's tail gun; the jet was subsequently renamed In HARM's Way.[201] Shortly following this incident, General George Lee Butler announced that the gunner position on B-52 crews would be eliminated, and the gun turrets permanently deactivated, commencing on 1 October 1991.[202]

Since the mid-1990s, the B-52H has been the only variant remaining in military service;[Note 6] it is currently stationed at:

- Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota – 5th Bomb Wing

- Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana – 2nd Bomb Wing (active Air Force) and 307th Bomb Wing (Air Force Reserve Command)

- One B-52H is assigned to Edwards Air Force Base and is used by Air Force Materiel Command at the USAF Flight Test Center.

- One additional B-52H is used by NASA at Dryden Flight Research Center, California as part of the Heavy-lift Airborne Launch program.[203]

From 2 to 3 September 1996, two B-52Hs conducted a mission as part of Operation Desert Strike. The B-52s struck Baghdad power stations and communications facilities with 13 AGM-86C conventional air-launched cruise missiles (CALCM) during a 34-hour, 16,000-mile round trip mission from Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, the longest distance ever flown for a combat mission.[204]

On 24 March 1999, when Operation Allied Force began, B-52 bombers bombarded Serb targets throughout the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, including during the Battle of Kosare.[205]

The B-52 contributed to Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001 (Afghanistan/Southwest Asia), providing the ability to loiter high above the battlefield and provide Close Air Support (CAS) through the use of precision guided munitions, a mission which previously would have been restricted to fighter and ground attack aircraft.[206] In late 2001, ten B-52s dropped a third of the bomb tonnage in Afghanistan.[207] B-52s also played a role in Operation Iraqi Freedom, which commenced on 20 March 2003 (Iraq/Southwest Asia). On the night of 21 March 2003, B-52Hs launched at least 100 AGM-86C CALCMs at targets within Iraq.[208]

B-52 and maritime operations

The B-52 can be highly effective for ocean surveillance, and can assist the Navy in anti-ship and mine-laying operations. For example, a pair of B-52s, in two hours, can monitor 140,000 square miles (364,000 square kilometers) of ocean surface. During the 2018 Baltops exercise B-52s conducted mine-laying missions off the coasts of Sweden, simulating a counter-amphibious invasion mission in the Baltic.[209][210]

In the 1970s, the U.S. Navy worried that combined attack from Soviet bombers, submarines and warships could overwhelm its defenses and sink its aircraft carriers. After the Falklands War, US planners feared the damage that could be created by 200-mile-range missiles carried by Tupolev Tu-22M "Backfire" bombers and 250-mile-range missiles carried by Soviet surface ships. New US Navy's maritime strategy in early 1980s called for aggressive use of carriers and surface action groups against the Soviet navy. To help protect the carrier battle groups, some B-52G were modified to fire Harpoon anti-ship missiles. These bombers were based at Guam and Maine from the later 1970s in order to support both the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. In case of war B-52s would coordinate with tanker support and surveillance by AWACS and Navy planes. B-52Gs could strike Soviet navy targets on the flanks of the US carrier battle groups, leaving them free to concentrate on offensive strikes against Soviet surface combatants. Mines laid down by B-52s could establish mine fields in significant enemy choke points (mainly the Kuril Islands and the GIUK gap). These minefields would force the Soviet fleet to disperse, making individual ships more vulnerable to Harpoon attacks.[211][212]

From the 1980s B-52Hs were modified to use Harpoons in addition to a wide range of cruise missiles, laser- and satellite-guided bombs and unguided munitions. B-52 bomber crews honed sea-skimming flight profiles that would allow them to penetrate stiff enemy defenses and attack Soviet ships.[213][214][215]

Recent expansion and modernization of China's navy has caused the USAF to re-implement strategies for finding and attacking ships. The B-52 fleet has been certified to use Quickstrike family of naval mines using JDAM-ER guided wing kits. This weapon provides the ability to lay down minefields over wide areas, in a single pass, with extreme accuracy, and all while standing-off at over 40 miles away. Besides this, with a view to enhance B-52 maritime patrol and strike performance, an AN/ASQ-236 Dragon's Eye underwing pod, has also been certified for use by B-52H bombers. Dragon's Eye contains an advanced electronically-scanned array radar that will allow B-52s to quickly scan vast Pacific Ocean areas, so finding and sinking enemy ships will be easier for them. This radar will complement the Litening infrared targeting pod already used by B-52s for inspecting ships.[216][217] In 2019, Boeing selected the Raytheon AN/APG-82(V)1 radar to replace its mechanically scanning AN/APQ-166 attack radar.[218][219]

Recent service

In August 2007, a B-52H ferrying AGM-129 ACM cruise missiles from Minot Air Force Base to Barksdale Air Force Base for dismantling was mistakenly loaded with six missiles with their nuclear warheads. The weapons did not leave USAF custody and were secured at Barksdale.[220][221]

Four of 18 B-52Hs from Barksdale Air Force Base were retired and were in the "boneyard" of 309th AMARG at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base as of 8 September 2008.[222]

As of January 2013, 78 of the original 744 B-52 aircraft were in operation with the USAF.[223]

In February 2015, hull 61-7 Ghost Rider became the first stored B52 to fly out of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base after six years in storage.[224]

B-52s are periodically refurbished at USAF maintenance depots such as Tinker Air Force Base, Oklahoma.[225] Even while the USAF works on the new Long Range Strike Bomber, it intends to keep the B-52H in service until 2045, which is 90 years after the B-52 first entered service, an unprecedented length of service for any aircraft, civilian or military.[199][226][227][228][Note 7]

The USAF continues to rely on the B-52 because it remains an effective and economical heavy bomber in the absence of sophisticated air defenses, particularly in the type of missions that have been conducted since the end of the Cold War against nations with limited defensive capabilities. The B-52 has also continued in service because there has been no reliable replacement.[230] The B-52 has the capacity to "loiter" for extended periods, and can deliver precision standoff and direct fire munitions from a distance, in addition to direct bombing. It has been a valuable asset in supporting ground operations during conflicts such as Operation Iraqi Freedom.[231] The B-52 had the highest mission capable rate of the three types of heavy bombers operated by the USAF in the 2000–2001 period. The B-1 averaged a 53.7% ready rate, the B-2 Spirit achieved 30.3%, while the B-52 averaged 80.5%.[192] The B-52's $72,000 cost per hour of flight is more than the B-1B's $63,000 cost per hour, but less than the B-2's $135,000 per hour.[232]

The Long Range Strike Bomber program is intended to yield a stealthy successor for the B-52 and B-1 that would begin service in the 2020s; it is intended to produce 80 to 100 aircraft. Two competitors, Northrop Grumman and a joint team of Boeing and Lockheed Martin, submitted proposals in 2014;[233] Northrop Grumman was awarded a contract in October 2015.[234]

On 12 November 2015, the B-52 began freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea in response to Chinese man-made islands in the region. Chinese forces, claiming jurisdiction within a 12-mile exclusion zone of the islands, ordered the bombers to leave the area, but they refused, not recognizing jurisdiction.[235] On 10 January 2016, a B-52 overflew parts of South Korea escorted by South Korean F-15Ks and U.S. F-16s in response to the supposed test of a hydrogen bomb by North Korea.[236]

On 9 April 2016, an undisclosed number of B-52s arrived at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar as part of Operation Inherent Resolve, part of the Military intervention against ISIL. The B-52s took over heavy bombing after B-1 Lancers that had been conducting airstrikes rotated out of the region in January 2016.[237] In April 2016, B-52s arrived in Afghanistan to take part in the war in Afghanistan and began operations in July, proving its flexibility and precision carrying out close-air support missions.[238]

According to a statement by the U.S. military, an undisclosed number of B-52s participated in the U.S. strikes on pro-government forces in eastern Syria on 7 February 2018.[239]

A number of B-52s were deployed in airstrikes against the Taliban during the 2021 Taliban offensive.[240]

In 2022, the US Air Force used a B-52 as a platform to test a Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) missile.[241] In late October 2022, ABC News reported that the USAF intended to deploy six B-52s at RAAF Tindal in Australia in the near future, which would include building provisions to handle the aircraft.[242]

Variants

| Variant | Produced | Entered Service |

|---|---|---|

| XB-52 | 2 (1 redesignated YB-52) | prototypes |

| YB-52 | 1 modified XB-52 | prototype |

| B-52A | 3 (1 redesignated NB-52A) | test units |

| NB-52A | 1 modified B-52A | |

| B-52B | 50 | 29 June 1955 |

| RB-52B | 27 Modified B-52Bs | |

| NB-52B | 1 Modified B-52B | 1955 |

| B-52C | 35 | June 1956 |

| B-52D | 170 | December 1956 |

| B-52E | 100 | December 1957 |

| B-52F | 89 | June 1958 |

| B-52G | 193 | 13 February 1959 |

| B-52H | 102 | 9 May 1961 |

| Grand total | 744 production |

The B-52 went through several design changes and variants over its 10 years of production.[134]

- XB-52

- Two prototype aircraft with limited operational equipment, used for aerodynamic and handling tests

- YB-52

- One XB-52 modified with some operational equipment and re-designated

- B-52A

- Only three of the first production version, the B-52A, were built, all loaned to Boeing for flight testing.[51] The first production B-52A differed from prototypes in having a redesigned forward fuselage. The bubble canopy and tandem seating was replaced by a side-by-side arrangement and a 21 in (53 cm) nose extension accommodated more avionics and a new sixth crew member.[Note 8] In the rear fuselage, a tail turret with four 0.50 inch (12.7 mm) machine guns with a fire-control system, and a water injection system to augment engine power with a 360 US gallon (1,363 L) water tank were added. The aircraft also carried a 1,000 US gallon (3,785 L) external fuel tank under each wing. The tanks damped wing flutter and also kept wingtips close to the ground for ease of maintenance.[243]

- NB-52A

- The last B-52A (serial 52-3) was modified and redesignated NB-52A in 1959 to carry the North American X-15. A pylon was fitted under the right wing between the fuselage and the inboard engines with a 6 feet x 8 feet (1.8 m x 2.4 m) section removed from the right wing flap to fit the X-15 tail. Liquid oxygen and hydrogen peroxide tanks were installed in the bomb bays to fuel the X-15 before launch. Its first flight with the X-15 was on 19 March 1959, with the first launch on 8 June 1959. The NB-52A, named "The High and Mighty One" carried the X-15 on 93 of the program's 199 flights.[244]

- B-52B/RB-52B

The B-52B was the first version to enter service with the USAF on 29 June 1955 with the 93rd Bombardment Wing at Castle Air Force Base, California.[243] This version included minor changes to engines and avionics, enabling an extra 12,000 pounds of thrust using water injection.[245] Temporary grounding of the aircraft after a crash in February 1956 and again the following July caused training delays, and at mid-year there were still no combat-ready B-52 crews.[140]

- Of the 50 B-52Bs built, 27 were capable of carrying a reconnaissance pod as RB-52Bs (the crew was increased to eight in these aircraft).[51] The 300 pound (136 kg) pod contained radio receivers, a combination of K-36, K-38, and T-11 cameras, and two operators on downward-firing ejection seats. The pod required only four hours to install.[140]

- Seven B-52Bs were brought to B-52C standard under Project Sunflower.[246]

- NB-52B

- The NB-52B was B-52B number 52-8 converted to an X-15 launch platform. It subsequently flew as "Balls 8" in support of NASA research until 17 December 2004, making it the oldest flying B-52B. It was replaced by a modified B-52H.[247]

- B-52C

- The B-52C's fuel capacity (and range) was increased to 41,700 US gallons by adding larger 3000 US gallon underwing fuel tanks. The gross weight was increased by 30,000 pounds (13,605 kg) to 450,000 pounds. A new fire control system, the MD-9, was introduced on this model.[168] The belly of the aircraft was painted with anti-flash white paint, which was intended to reflect the thermal radiation of a nuclear detonation.[248]

- RB-52C

- The RB-52C was the designation initially given to B-52Cs fitted for reconnaissance duties in a similar manner to RB-52Bs. As all 35 B-52Cs could be fitted with the reconnaissance pod, the RB-52C designation was little used and was quickly abandoned.[248]

- B-52D

- The B-52D was a dedicated long-range bomber without a reconnaissance option. The Big Belly modifications allowed the B-52D to carry heavy loads of conventional bombs for carpet bombing over Vietnam,[245] while the Rivet Rambler modification added the Phase V ECM systems, which was better than the systems used on most later B-52s. Because of these upgrades and its long range capabilities, the D model was used more extensively in Vietnam than any other model.[168] Aircraft assigned to Vietnam were painted in a camouflage color scheme with black bellies to defeat searchlights.[71]

- B-52E

- The B-52E received an updated avionics and bombing navigational system, which was eventually debugged and included on following models.[245]

- JB-52E

- One aircraft leased by General Electric to test TF39 and CF6 engines.[245]

- NB-52E

- One -E aircraft (AF Serial No. 56-632) was modified as a testbed for various B-52 systems. Redesignated NB-52E, the aircraft was fitted with canards and a Load Alleviation and Mode Stabilization system which reduced airframe fatigue from wind gusts during low level flight. In one test, the aircraft flew 10 knots (11.5 mph, 18.5 km/h) faster than the never exceed speed without damage because the canards eliminated 30% of vertical and 50% of horizontal vibrations caused by wind gusts.[249][250][251]

- B-52F

- This aircraft was given J57-P-43W engines with a larger capacity water injection system to provide greater thrust than previous models.[245] This model had problems with fuel leaks which were eventually solved by several service modifications: Blue Band, Hard Shell, and QuickClip.[96]

- B-52G

- The B-52G was proposed to extend the B-52's service life during delays in the B-58 Hustler program. At first, a radical redesign was envisioned with a completely new wing and Pratt & Whitney J75 engines. This was rejected to avoid slowdowns in production, although a large number of changes were implemented.[245] The most significant of these was a new "wet" wing with integral fuel tanks, increasing gross aircraft weight by 38,000 pounds (17,235 kg). In addition, a pair of 700 US gallon (2,650 L) external fuel tanks were fitted under the wings on wet hardpoints.[252] The traditional ailerons were also eliminated, and the spoilers now provided all roll control (roll control had always been primarily with spoilers due to the danger of wing twist under aileron deflection, but older models had small "feeler" ailerons fitted to provide feedback to the controls). The tail fin was shortened by 8 feet (2.4 m), water injection system capacity was increased to 1,200 US gallons (4,540 L), and the nose radome was enlarged.[253] The tail gunner was relocated to the forward fuselage, aiming via a radar scope, and was now provided with an ejection seat.[252] Dubbed the "Battle Station" concept, the offensive crew (pilot and copilot on the upper deck and the two bombing navigation system operators on the lower deck) faced forward, while the defensive crew (tail gunner and ECM operator) on the upper deck faced aft.[168] The B-52G entered service on 13 February 1959 (a day earlier, the last B-36 was retired, making SAC an all-jet bomber force). 193 B-52Gs were produced, making this the most produced B-52 variant. Most B-52Gs were destroyed in compliance with the 1992 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty; the last B-52G, number 58-224, was dismantled under New START treaty requirements in December 2013.[254] A few examples remain on display for museums.[255]

- B-52H

- The B-52H had the same crew and structural changes as the B-52G. The most significant upgrade was the switch to TF33-P-3 turbofan engines, which, despite the initial reliability problems (corrected by 1964 under the Hot Fan program), offered considerably better performance and fuel economy than the J57 turbojets.[168][253] The ECM and avionics were updated, a new fire control system was fitted, and the rear defensive armament was changed from machine guns to a 20 mm M61 Vulcan cannon (later removed in 1991–94).[252] The final 18 aircraft were manufactured with provision for the ADR-8 countermeasures rocket, which was later retrofitted to the remainder of the B-52G and B-52H fleet.[256] A provision was made for four GAM-87 Skybolt ballistic missiles. The aircraft's first flight occurred on 10 July 1960, and it entered service on 9 May 1961. This is the only variant still in use.[3] A total of 102 B-52Hs were built. The last production aircraft, B-52H AF Serial No. 61-40, left the factory on 26 October 1962.[257]

- XR-16A

- Allocated to the reconnaissance variant of the B-52B, but not used. The aircraft were designated RB-52B instead.[258]

Operators

- United States Air Force 76 aircraft in service as of February 2015[259]

- Air Combat Command

- 53d Wing – Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

- 49th Test and Evaluation Squadron (Barksdale)

- 57th Wing – Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada

- 340th Weapons Squadron (Barksdale)

- 53d Wing – Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

- Air Force Global Strike Command

- 2d Bomb Wing – Barksdale Air Force Base , Louisiana

- 11th Bomb Squadron

- 20th Bomb Squadron

- 96th Bomb Squadron

- 5th Bomb Wing – Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota

- 23d Bomb Squadron

- 69th Bomb Squadron

- 2d Bomb Wing – Barksdale Air Force Base , Louisiana

- Air Force Materiel Command

- 412th Test Wing – Edwards Air Force Base, California

- 419th Flight Test Squadron

- 412th Test Wing – Edwards Air Force Base, California

- Air Force Reserve Command

- 307th Bomb Wing – Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana

- 93d Bomb Squadron

- 343d Bomb Squadron

- 307th Bomb Wing – Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana

- Air Combat Command

- NASA

- Dryden Flight Research Center

- 1 modified ex-USAF NB-52B (52-8) "Mothership" Launch Aircraft operated from 1966 to 2004. It was then put on display at the North entrance to Edwards Air Force Base.[260]

- 1 modified ex-USAF B-52H (61-25) Heavy Lift Launch Aircraft operated from 2001 to 2008. On 9 May 2008, that aircraft was flown for the last time to Sheppard Air Force Base, Texas, where it became a GB-52H maintenance trainer, never to fly again.[261]

- Dryden Flight Research Center

Notable accidents

- On 10 January 1957, a B-52B returning to Loring Air Force Base from a routine instrument training mission broke apart in midair and crashed near Morrell, New Brunswick, killing eight of the nine crew on board. Co-pilot Captain Joseph L. Church parachuted to safety. The crash was believed to have been caused by overstressing the wings and/or airframe during an exercise designed to test the pilot's reflexes. This was the fourth crash involving a B-52 in 11 months.[262]

- On 11 February 1958, a B-52D crashed in South Dakota because of ice blocking the fuel system, leading to an uncommanded reduction in power to all eight engines. Three crew members were killed.[263]

- On 8 September 1958, two B-52Ds collided in midair near Fairchild Air Force Base, Washington; all 13 crew members on the 2 aircraft were killed.[264]

- On 15 October 1959, a B-52F from the 492d Bomb Squadron at Columbus Air Force Base, Mississippi, carrying two nuclear weapons collided in midair with a KC-135 tanker near Hardinsburg, Kentucky; four of the eight crew members on the bomber and all four crew on the tanker were killed. One of the nuclear bombs was damaged by fire, but both weapons were recovered.[264]

- On 24 January 1961, a B-52G broke up in midair and crashed after suffering a severe fuel loss, near Goldsboro, North Carolina, dropping two nuclear bombs in the process without detonation.[265] Three of the eight crew members were killed.

- On 14 March 1961, a B-52F from Mather Air Force Base, California,[266] carrying two nuclear weapons experienced an uncontrolled decompression, necessitating a descent to 10,000 feet to lower the cabin altitude. Due to increased fuel consumption at the lower altitude and unable to rendezvous with a tanker in time, the aircraft ran out of fuel. The crew ejected safely, while the unmanned bomber crashed 15 miles (24 km) west of Yuba City, California.[267]

- On 24 January 1963, a B-52C on a training mission out of Westover Air Force Base, Massachusetts, lost its vertical stabilizer due to buffeting during low-level flight, and crashed on the west side of Elephant Mountain near Greenville, Maine. Of the nine crewmen aboard, two survived the crash.[268][269]

- On 13 January 1964, the vertical stabilizer broke off a B-52D in winter storm turbulence; it crashed on Savage Mountain in western Maryland. The two nuclear bombs being ferried were found "relatively intact"; three of the crew of five died.[270]

- On 18 June 1965, two B-52Fs collided mid-air during a refueling maneuver at 33,000 feet (10,000 m) above the South China Sea. The head-on collision took place just northwest of the Luzon Peninsula, Philippines, in the night sky above Super Typhoon Dinah, a category 5 storm with maximum winds of 185 mph (298 km/h) and waves reported as high as 70 feet (21 m). Eight of twelve total crew members in two planes were killed. The rescue of four crew members who had managed to eject only to parachute into one of the largest typhoons of the 20th century remains one of the most remarkable survival stories in the history of aviation. The crash was also notable, because it was the first combat mission ever for the B-52.[271] The two jets were part of a 30-plane squadron on an inaugural Arc Light mission from Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, to a military target about 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Saigon, South Vietnam.[272][273]

- On 17 January 1966, a fatal collision occurred between a B-52G and a KC-135 Stratotanker over Palomares, Spain, killing all four on the tanker and three of the seven on the B-52G. The two unexploded B-28 FI 1.45-megaton-range nuclear bombs on the B-52 were eventually recovered; the conventional explosives of two more bombs detonated on impact, with serious dispersion of both plutonium and uranium, but without triggering a nuclear explosion. After the crash, 1,400 metric tons (3,100,000 lb) of contaminated soil was sent to the United States.[274] In 2006, an agreement was made between the U.S. and Spain to investigate and clean the pollution still remaining as a result of the accident.[275]

- On November 18, 1966, the crew departed Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, on a training flight to Kenneth Ingalls Sawyer AFB. The goal of the mission was to test the performances of a new ground reconnaissance radar. While cruising by night at low altitude, the airplane struck trees, stalled and crashed south of Stone Lake. All nine crew members were killed.[276]