History of the New York Yankees

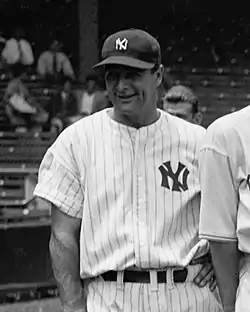

The history of the New York Yankees Major League Baseball (MLB) team spans more than a century. Frank J. Farrell and William Stephen Devery bought the rights to an American League (AL) club in New York City after the 1902 season. The team, which became known as the Yankees in 1913, rarely contended for the AL championship before the acquisition of outfielder Babe Ruth after the 1919 season. With Ruth in the lineup, the Yankees won their first AL title in 1921, followed by their first World Series championship in 1923. Ruth and first baseman Lou Gehrig were part of the team's Murderers' Row lineup, which led the Yankees to a then-AL record 110 wins and a Series championship in 1927 under Miller Huggins. They repeated as World Series winners in 1928, and their next title came under manager Joe McCarthy in 1932.

The Yankees won the World Series every year from 1936 to 1939 with a team that featured Gehrig and outfielder Joe DiMaggio, who recorded a record hitting streak during New York's 1941 championship season. New York set a major league record by winning five consecutive championships from 1949 to 1953, and appeared in the World Series nine times from 1955 to 1964. Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford were among the players fielded by the Yankees during the era. After the 1964 season, a lack of effective replacements for aging players caused the franchise to decline on the field, and the team became a money-loser for owners CBS while playing in an aging stadium.

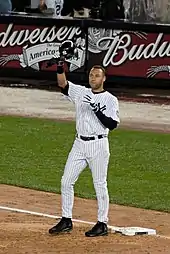

George Steinbrenner bought the club in 1973 and regularly invested in new talent, using free agency to acquire top players. Yankee Stadium was renovated and reopened in 1976 as the home of a more competitive Yankees team. Despite clubhouse disputes, the team reached the World Series four times between 1976 and 1981 and claimed the championship in 1977 and 1978. New York continued to pursue their strategy of signing free agents into the 1980s, but with less success, and the team eventually sank into mediocrity after 1981. In the early 1990s, the team began to improve as their roster was rebuilt around young players from their minor league system, including Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera. After earning a playoff berth in 1995, the Yankees won four of the next five World Series, and the 1998–2000 teams were the last in MLB to win three straight Series titles.

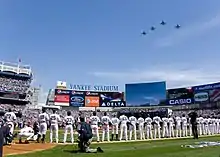

As the 2000s progressed, the Yankees' rivalry with the Boston Red Sox increased in intensity as the sides met multiple times in the American League Championship Series (ALCS), trading victories in 2003 and 2004. New York regularly reached the postseason, but were often defeated in the first two rounds. In 2009, the Yankees opened a new Yankee Stadium and won the World Series for the 27th time in team history, an MLB record. The Yankees appeared in the ALCS four times during the 2010s, but lost on each occasion.

As of 2022, the Yankees' 27 World Series championships are 16 more than the number won by the St. Louis Cardinals, who have the second-most titles among MLB teams.[1] New York's championship total is the highest of any franchise in a major North American professional sports league; the National Hockey League's Montreal Canadiens are second behind the Yankees with 24 Stanley Cup wins.[2] The 40 pennants won by the Yankees places them 17 in front of the Cardinals for the most won by an MLB team. The Giants and Dodgers are the only other clubs with 20 or more pennants.[1] The Baseball Hall of Fame has inducted over 40 players and managers who have worn Yankees pinstripes.[3] Forbes magazine has labeled the Yankees the most valuable team in baseball every year since 1998; the franchise was worth an estimated $5 billion in 2020.[4]

In Glenn Stout's Yankees history book, the author wrote:

More often than not, they have shown just how the game of baseball is supposed to be played. Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Mantle, Mattingly, Jeter, and dozens of other players impossible to forget have worn their uniform. Yankee Stadium has been their stage. The very definition of a dynasty, they have created the collective memories that make friends of strangers, given their city a face, and displayed its heart and soul.[5]

Pre-World War II

Background: 1901–1902 Baltimore Orioles

At the end of the 1900 baseball season, the Western League was positioned by its president, Ban Johnson, as a new major league that would compete with the established National League (NL). The league was reorganized and renamed the American League (AL), and eight cities fielded teams in the 1901 season. A Baltimore team had played in the NL through the 1899 season, after which the club was shut down by the league. Baltimore was one of three former NL cities where the AL placed teams in an effort to reach underserved fans.[6] The new Orioles' first manager was John McGraw, who had held the same position for the previous Baltimore team in 1899; McGraw also held an ownership stake.[7]

In 1901, their first season, the Orioles had a 68–65 win–loss record and finished in fifth place in the AL.[8] During the season, there were numerous disputes between Johnson and McGraw over disciplinary issues, which continued into the following year.[9] Rumors began to spread that Johnson was interested in relocating the team to New York City, in an attempt to compete directly with the NL. McGraw left the Orioles and joined the New York Giants as their manager; he transferred his interest in the Baltimore team to the Giants as part of the deal.[10] Several Orioles—including Roger Bresnahan and Joe McGinnity—joined the Giants after McGraw's departure, and the Giants gained a majority of the Orioles' stock. The league managed to take back control of the team from the Giants; after the Orioles forfeited a game because they lacked enough active players,[11] Johnson ordered that the team be "restocked with players essentially given away by the other teams in order to play out the schedule", according to author Marty Appel.[12] The Orioles finished last in the league both in the standings and in attendance.[13]

The AL and NL signed an agreement after the 1902 season that ended the leagues' battles for players, which had led to increasing salaries. Johnson sought the right to locate an AL team in New York City, which was granted as part of the leagues' peace agreement. His intention was for the team to play in Manhattan, but the idea was opposed by Giants owner John T. Brush and former owner Andrew Freedman, who were connected to the city's Tammany Hall political organization. They blocked several potential stadium locations, before a pair of Tammany Hall politicians, Frank J. Farrell and William Stephen Devery, purchased the New York franchise in the AL.[14] The pair paid US$18,000 for the team. It is not clear whether Farrell and Devery purchased the remains of the Orioles and moved them to New York, or if they received an expansion franchise.[15][note 1] It was the last change in the lineup of MLB teams for half a century.[18]

1903–1912: Early years

The ballpark for the New York team was constructed between 165th and 168th Streets, on Broadway in Manhattan. Formally known as American League Park, it was nicknamed Hilltop Park because of its relatively high elevation.[19] The team did not have an official nickname; it was often called the New York Americans in reference to the AL. Another common nickname for the club was the Highlanders, a play on the last name of the team's president, Joe Gordon, and the British military unit, the Gordon Highlanders.[20] The team acquired players such as outfielder Willie Keeler and pitcher Jack Chesbro. The player-manager was Clark Griffith, obtained from the Chicago White Sox. On April 22, 1903, the Highlanders began their season with a 3–1 loss to the Washington Senators; eight days later, they won their first game in Hilltop Park, defeating the Senators 6–2. New York fell out of contention for the AL pennant in May, falling to seventh place after playing games away from Hilltop Park for a 24-day period while construction on the stadium concluded. With a final record of 72–62 after wins in 19 of 29 games played in September, New York finished in fourth.[21]

Chesbro won 41 games in New York's 1904 season, still an AL record.[22] New York contended for the AL pennant with the Boston Americans (later nicknamed the Red Sox); Johnson aided New York by helping the team acquire multiple players in trades, including Boston's Patsy Dougherty. Boston and New York faced each other in a season-ending five-game series that decided the pennant winner, and was played from October 7–10. Boston won two of the first three games, which meant that New York needed to win the two contests scheduled on October 10 to win the AL title. With the score of the first game tied 2–2 in the ninth inning, Chesbro threw a wild pitch that allowed a runner on third base to score, giving Boston a 3–2 victory that clinched the AL pennant; New York won the now-meaningless second game.[23]

New York's performance declined in 1905, as numerous pitchers dealt with arm injuries and conditioning issues. After losing 18 of 25 games in May, the Highlanders ended the season in sixth.[24] In its 1906 season, New York again contended for the AL championship. With 13 games left, the team held a one-game lead over the White Sox, but finished in second place three games behind Chicago.[25] According to Appel, "What would follow would be a string of mediocre to bad seasons and not a very good attraction for baseball-crazed New York fans."[26] New York recorded a fifth-place finish in 1907, with 70 wins, 22 fewer than the league champion Detroit Tigers.[27] The 1908 and 1909 teams finished last and fifth, respectively, and there were multiple managerial changes in the period.[28]

New York had a second-place finish in 1910, but did not seriously contend for the pennant. Manager George Stallings and first baseman Hal Chase, the team captain, clashed towards the end of the season; facing opposition from Ban Johnson, who wanted him to resign as manager, Stallings left the position. Chase managed New York's last 14 games.[29] The following season, New York had a sixth-place finish.[30] Early in the season, New York allowed the Giants to play in Hilltop Park after the Giants' stadium, the Polo Grounds, burned down; the arrangement lasted until June 28, when the rebuilt Polo Grounds opened.[31] Chase resigned as manager before New York's 1912 season; Harry Wolverton accepted the position.[32] That year, New York had a last-place finish with a record of 50–102, the winning percentage of .329 the lowest-ever for the club.[33]

After their first couple of seasons in New York City, team ownership infrequently invested in new players. The ownership group of Farrell and Devery spent their money on personal pursuits such as gambling, leaving them with little to put into the team. New York's star player, Chase, consorted frequently with gamblers. Author Jim Reisler dubbed him "the most crooked player to ever play the game" because of reports that he took part in game fixing.[34] The club also had difficulty drawing fans to Hilltop Park.[35] Appel wrote that "maybe the best thing you could say about the ballpark was that it never burned down."[36] By the end of the 1912 season, Farrell was searching for a site to build a new stadium on.[37]

1913–1920: New ownership and acquisition of Babe Ruth

New York started playing home games at the Polo Grounds in 1913 as tenants of the Giants.[38] Before the 1913 season, the team gained an official nickname for the first time. Either "Yankees" or "Yanks" had been used frequently since 1904 in newspapers such as the New York Evening Journal, since "Highlanders" was hard to fit in headlines.[39] Such unofficial nicknames were common during that era,[20] but thereafter the official name took hold—the New York Yankees.[40]

A third major league, the Federal League (FL), began play in 1914 and lasted for two years. While the Yankees did not have to contend with direct competition for fans, as the FL chose to place its New York City franchise in Brooklyn instead of Manhattan,[41] the team nearly lost leading pitcher Ray Caldwell to the rival league after the 1914 season.[42] With the Yankees finishing seventh in 1913 and sixth in 1914,[43] Farrell and Devery sold the team to brewery magnate Jacob Ruppert and former United States Army engineer Tillinghast L'Hommedieu Huston.[44] The Yankees had rarely been profitable over the previous 10 years, and carried debts of $20,000.[45] The sale was completed on January 11, 1915, as the pair paid a combined $460,000. Ruppert called the team "an orphan ball club, without a home of its own, without players of outstanding ability, without prestige."[46] The new owners intended to spend freely to improve the club's talent level and made a major purchase in 1915, buying pitcher Bob Shawkey from the Philadelphia Athletics. In spite of this, the Yankees' 69 wins were only enough for fifth in the league.[47] After wearing different designs during the Highlanders years, in 1915 the Yankees introduced white uniforms with pinstripes and an interlocking "NY" logo during games at the Polo Grounds; this remains their home uniform design today. For road games, the team began to wear gray uniforms with "New York" across the chest from 1913; the Yankees still wear similar garb.[48][49]

Following the acquisition of third baseman Frank "Home Run" Baker from the Athletics,[50] the 1916 Yankees had 80 wins and contended for the AL pennant for most of the season, before suffering a run of injuries to key players, including Baker.[51] In the Yankees' 1917 season, New York finished in sixth; Bill Donovan, the club's manager since 1915, was fired in the offseason.[52] Ruppert replaced him with Miller Huggins, completing the hire while Huston was overseas fighting in World War I.[53] The Yankees contended for first place in the war-shortened 1918 campaign along with the Red Sox and Cleveland Indians, but lost numerous players to military service and were fourth at 60–63.[54] After the season, the Yankees acquired three players—including outfielder Duffy Lewis and pitcher Ernie Shore—in a trade with the Red Sox, the winners of the 1918 World Series. In 1919, the club made another trade with Boston, acquiring pitcher Carl Mays for two players and $40,000. The midseason deal provoked a dispute between the teams and Ban Johnson, who unsuccessfully attempted to block it.[55] Mays had a 9–3 pitching record as a Yankee, and the team improved to 80–59 for the season; the mark was good for third in the AL.[56]

The 1919 season was the first in which the Yankees played games at the Polo Grounds on Sundays; until then, blue laws had banned Sunday baseball in New York state. The Yankees' attendance more than doubled in 1919, rising to about 619,000.[57] The Giants soon moved to force the Yankees out of the Polo Grounds, in an effort to secure more Sunday home games.[58] On December 26, 1919, the Yankees made an agreement with the Red Sox to purchase outfielder Babe Ruth for $25,000 cash and $75,000 in promissory notes. The deal, which was announced on January 5, 1920, was called "the most famous transaction in sports" by author Glenn Stout.[59] After tying for the MLB home run lead in 1918 with the Athletics' Tilly Walker (with 11), Ruth broke the single-season record with 29 in 1919.[60] At the same time, he sought a new contract that would double his $10,000 yearly salary.[61] After the trade, Boston did not win another World Series championship until 2004; an alleged jinx against the Red Sox, which was known as the Curse of the Bambino (after a nickname for Ruth), was first brought up when they lost the 1986 World Series and became widely discussed after Dan Shaughnessy authored a book with the title.[62] The deal became a symbol of "how things [would] always go wrong for the Red Sox and right for the Yankees", according to Stout.[63]

With Ruth in the lineup, the Yankees' fortunes were transformed.[64] Playing on four World Series champion teams,[65] Ruth hit 659 home runs and scored 1,959 runs with the Yankees; both marks are team records as of 2021. He is second in club history with 1,978 runs batted in and accumulated 2,518 hits as a Yankee, third on the team's all-time list.[66] As well as prowess on the field, Ruth had a larger-than-life personality, bringing him and his team a huge amount of press and public attention.[67] The addition of Ruth helped the Yankees increase their attendance to 1,289,422 for the 1920 season; it was the first time that any MLB team drew more than one million fans in a year.[68] His skills and charm appealed to large segments of the New York City population; Stout wrote that "He belonged to everyone."[69] New York was the AL attendance leader for 13 of Ruth's 15 seasons with the team; the Yankees became solidly profitable as well, making over $370,000 in 1920 and remaining in the black for the rest of the decade.[70]

In 1920, Ruth hit 54 home runs for a new record; his total was higher than that of all other MLB teams but the Philadelphia Phillies. New York had 95 wins, the most in team history to that point, but fell three wins short of the AL championship and finished third.[71] In an August 16 game against the Indians, a pitch from Mays hit Indians shortstop Ray Chapman in the head, leading to his death; the Yankees slumped after the incident as Cleveland captured the pennant.[72] After the season, the Yankees hired general manager Ed Barrow from the Red Sox. Barrow made numerous trades with his former club, including one immediately after his departure that brought catcher Wally Schang and pitcher Waite Hoyt to New York.[73] The Yankees also became involved in another dispute with Ban Johnson, this time over the replacement of baseball's existing governing body, the National Commission, after reports came out that the 1919 World Series had been fixed. The Yankees and 10 other franchises—including the entire NL—supported the idea of a three-man committee drawn from outside baseball running MLB, and for a time a move by the Yankees to the NL was rumored; ultimately, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was named MLB's first commissioner.[74]

1921–1928: First World Series win and Murderers' Row

The 1921 season began a 44-year period in which the Yankees were, according to author Richard Worth, "The greatest sustained winning 'empire' in sports".[75] Ruth surpassed his own record by hitting 59 home runs. He also led MLB in on-base percentage with a .512 mark for the season.[76] The Yankees won the AL pennant for the first time, winning 98 games in the regular season; the total gave them the league championship by a margin of 4+1⁄2 games over Cleveland. In the best-of-nine 1921 World Series, they faced the Giants and won the first two games, but their opponents claimed the Series title when they won five of the next six games. Ruth suffered an arm infection, which limited his playing time in the later part of the Series.[77] He and Bob Meusel participated in exhibition games during the offseason, in violation of MLB rules forbidding players on pennant-winning teams from barnstorming after the World Series. Season-long suspensions were considered a possibility, but Landis decided to suspend the pair for six weeks.[78] Despite the setback, New York had 94 wins and repeated as AL champions. The St. Louis Browns were the closest pursuers, finishing one game behind New York. In the World Series, the Yankees again faced the Giants in an all-New York matchup; the Series changed to a best-of-seven format that year. The Giants defeated the Yankees in five games, including one that ended in a tie when it was suspended because of darkness.[79]

By 1923, the teams no longer shared the Polo Grounds, as Giants owner Charles Stoneham had attempted to evict the Yankees in 1920. Although the attempt was unsuccessful,[80] and Stoneham and the Yankees' owners agreed to a two-year lease renewal,[81] the Giants decided against giving the Yankees an extension after 1922.[82] The treatment pushed the Yankees into seeking their own stadium. In 1921, the team bought a plot of land in the Bronx, and the construction crew finished the new ballpark before the 1923 season.[83] Yankee Stadium, a triple-deck facility, was originally designed to hold more than 55,000 spectators; it was later able to hold over 70,000.[84] Writer Peter Carino called the stadium "a larger and more impressive facility than anything yet built to house a baseball team."[85] At Yankee Stadium's inaugural game on April 18, 1923, Ruth hit the first home run in the stadium, which sportswriter Fred Lieb named "the House That Ruth Built" as the Yankees would not have needed such a large stadium without the Ruth-driven attendance. Ruth himself had a resurgence after receiving vocal criticism for his 1922 World Series performance. He shared the MLB lead with Cy Williams by hitting 41 home runs in the 1923 season, and had a career-best .393 batting average; his performance earned him the AL Most Valuable Player (MVP) Award.[86][87] The Yankees finished first for the third consecutive year, and faced the Giants again in the 1923 World Series. Giants outfielder Casey Stengel hit game-winning home runs in two of the first three games of the World Series, but Ruth's three home runs helped the Yankees win in six games for their first MLB title.[88] Off the field, Ruppert purchased Huston's share of the Yankees for $1.25 million, assuming full ownership of the club.[89]

The Yankees did not return to the World Series in either of the following two seasons. By 1925, New York had fallen to seventh place.[90] That year marked the team's last losing season until 1965; the 39-year streak of winning seasons is an MLB record.[91] Lou Gehrig became the starting first baseman in 1925, earning a spot in the lineup he would not relinquish for almost 15 years, a then-record consecutive games played streak.[92] The Yankees made more talent upgrades before their 1926 season, which included the signing of infielder Tony Lazzeri, who spent over a decade with the club. New York's performance on the field surpassed preseason expectations, and a 16-game winning streak in May gave the team a substantial lead. With a three-game final margin over the Indians, the Yankees won the pennant and a spot in the 1926 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals.[93] After the Yankees took a 3–2 series lead, the Cardinals won the final two games in Yankee Stadium to claim the Series title. Ruth hit three home runs in the fourth game, but made the final out of the Series on a failed stolen base attempt.[94]

The Yankees' lineup in the 1927 season, which featured Ruth, Gehrig, Lazzeri, Meusel, Mark Koenig, and Earle Combs, was known as Murderers' Row for its power hitting. The team led in the standings throughout.[95] The Yankees took first place in early May, and by the end of June had posted a 49–20 record, giving them a large lead in the AL standings; by mid-September, they had clinched the pennant.[96] The 1927 Yankees had a 110–44 record in the regular season, and broke the AL record for wins in a year.[97] Ruth's total of 60 home runs set a single-season home run record that stood for 34 years.[60] Gehrig added 47 home runs and his 175 RBI topped the AL; he won the first of his two AL MVP Awards.[98] The Yankees completed the season by sweeping the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1927 World Series.[99] The 1927 Yankees squad is included among the great teams in baseball history.[100]

To begin the 1928 season, the Yankees went on a 34–8 run and took a sizable lead. The Athletics chased them for the AL pennant towards the end of the season, but New York won the title again and faced the Cardinals in the 1928 World Series, sweeping them in four games. Coming off a 54-home run regular season, Ruth had three more and a .625 batting average in the Series, while Gehrig batted .545 with four home runs.[101] With the Yankees' run of three straight league pennants and two World Series titles came criticism from fans of other teams, who decried the team's dominance. Calls to "Break up the Yankees!" were made, and critics hoped that the team would sell Gehrig to separate him from Ruth; Ruppert declined to do so.[102]

1929–1935: Hiring of Joe McCarthy and Ruth's called shot

The Yankees' run of pennants was broken up by a rising Philadelphia Athletics team, which denied the Yankees a fourth straight AL championship in 1929.[103] The team's manager, Huggins, died on September 25. After Art Fletcher managed for the rest of the year, Shawkey took the position for the 1930 season, in which the Yankees had a third-place finish.[104] The Yankees fired Fletcher and hired Joe McCarthy; in his first season as manager, the team won 94 games but finished second behind the Athletics.[105] McCarthy's team was undergoing a transition from Murderers' Row; new contributors included Bill Dickey, who had first played for the Yankees in 1928, and pitchers Red Ruffing and Lefty Gomez.[106] Ruffing, who had a 39–96 record with the Red Sox before being traded to New York, ended up 231–124 in his Yankees career.[107]

In 1932, McCarthy's Yankees returned to the top of the AL with 107 wins, enough for a 13-game margin over the Athletics.[108] The Yankees met the Chicago Cubs in the 1932 World Series and swept them four games to none. Gehrig had three home runs, eight RBI, and a .529 batting average for the Series, while Ruth contributed a pair of home runs in the third game at Chicago's Wrigley Field. The second of Ruth's home runs was his "called shot"; after pointing towards the center field stands, according to some post-game press reports, Ruth homered to break a 4–4 tie in the fifth inning. Although accounts of the incident vary greatly, author Eric Enders called the home run "the most talked-about hit in baseball history".[109]

The Yankees began cutting their payroll in 1933, as their finances were strained by the Great Depression. Regardless, the makeup of the team was minimally impacted in comparison to the Athletics, who were forced to sell key players to lower their expenses.[110] From 1933 to 1935, the Yankees posted three consecutive second-place finishes.[111] Ruth's performance declined from previous seasons in 1933 and 1934, his final years with the team. The Yankees released Ruth from his contract before the 1935 season, and Gehrig took a leadership role for the club; he was named New York's captain.[112] New York was beginning to see results from an initiative to buy minor league teams in an effort to reduce the cost of obtaining players; after buying their first minor league club in 1929, the Yankees had a 15-team system by 1937. Players developed in the farm system entered the Yankee lineup beginning in the mid-1930s, and into the early 1960s this remained the team's primary player acquisition method.[113] McCarthy worked to regulate player behavior in areas such as mental focus and off-field attire; the Yankees acquired a "corporate image" that they retained for many years.[114]

1936–1941: Renewed domination

.jpg.webp)

New York's 1936 season was Joe DiMaggio's first with the club. The young center fielder was signed in 1934 from the Pacific Coast League's San Francisco Seals, and made his debut with the Yankees in 1936, gaining an extra year's experience with the Seals. DiMaggio had a .323 batting average, 29 home runs, and 125 RBI in his rookie season. Gehrig won the AL MVP Award for his season, in which he hit a career-high 49 home runs, with a .354 batting average and 152 RBI. Behind these performances, the Yankees had a 102-win season and won the AL pennant, before defeating the Giants in the 1936 World Series, four games to two.[115] After a second consecutive 102-win regular season and AL championship in the 1937 season, the Yankees again defeated the Giants in the Series—this time winning 4–1.[116] The 1938 Yankees had 48 victories in 61 games during one stretch, and won the team's third straight AL championship despite a drop in batting performance by Gehrig. In the 1938 World Series, the Yankees swept the Chicago Cubs in four games. Ruppert died early in 1939; before his death, he sold his ownership interest to Barrow, who took over as the Yankees' president.[117] Financially, the club's position had improved from earlier in the decade; after posting a net loss of around $170,000 from 1931 to 1935, the team made over $1 million during the next four years.[118]

The 1939 Yankees lost the services of Gehrig early in the season. After starting the year poorly, he was replaced by Babe Dahlgren, ending his streak of 2,130 consecutive games played; he was later diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which forced him to retire.[119] Despite the loss of Gehrig, New York fielded a team that posted 106 victories in 1939, 17 more than the second-place team. DiMaggio was named MVP of the league; he led the AL in batting average (.381) and was second in RBI (126). Ruffing led the Yankees' pitchers with 20 wins. In the 1939 World Series, the Yankees swept the Cincinnati Reds in four games for the club's fourth consecutive Series championship.[120] Writers have given the 1936–39 Yankees acclaim for their success in regular season and World Series play; Stout wrote that the 1939 squad was "magnificent", and that their campaign was "wholly without drama" besides Gehrig's departure from the lineup.[121] In response to the Yankees' dominance, after the 1939 season the AL temporarily barred most transactions between the last pennant winner and other league teams in an attempt to prevent New York from improving its roster.[122] The Yankees' run of championships ended in 1940; the team had 18 more losses than in the previous season and finished third, two games behind the Tigers.[123]

DiMaggio recorded base hits in 56 consecutive games for the Yankees during the 1941 season, breaking the MLB record of 44 games that had been set by Willie Keeler in 1897. His hitting streak began on May 15 and lasted until July 17, when DiMaggio failed to record a hit during a game against the Indians at Cleveland Stadium.[124] After winning the AL pennant, the Yankees met the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1941 World Series, prevailing in five games. In Game 4, the Yankees trailed 4–3 in the ninth inning and were on the verge of defeat when Tommy Henrich struck out; Dodgers catcher Mickey Owen was unable to field the pitch, allowing Henrich to reach base. That began a four-run game-winning rally, and New York won the championship in Game 5 the following day.[125]

World War II to free agency

1942–1947: Pre-Stengel era

The attack on Pearl Harbor occurred during the offseason, and some baseball players immediately joined the Armed Forces. Most of the Yankees' roster remained with the team in 1942, and the club repeated as AL champions despite Gomez's departure. In the 1942 World Series, the Cardinals gave the Yankees their first Series loss since 1926, after winning in eight consecutive appearances.[126][127] DiMaggio and other Yankees entered the military before the 1943 season, but the club won the AL championship for the 14th time and 7th since 1936. The Cardinals met the Yankees in a World Series rematch, and New York won four games to one.[128]

After 1943, more of the team's players were drafted into military, and the Yankees ended 1944 in third place, one position higher than they finished the following season.[129] A group consisting of Larry MacPhail, Dan Topping, and Del Webb bought the Yankees, their stadium, and the franchise's minor league teams for $2.8 million in 1945.[130] Under the new ownership, Yankee Stadium underwent extensive renovations that included the installation of lights. With the war over and the return of players from overseas, the Yankees set an MLB single-season home attendance record by attracting 2,265,512 fans in 1946. McCarthy resigned as manager early in the season. The Yankees used two other managers during the year (Bill Dickey and Johnny Neun), and ended 1946 in third place.[131] Catcher Yogi Berra made his Yankees debut that year; in his 18-season career, Berra won the AL MVP Award three times.[132] Bucky Harris was brought in to be the manager, and his 1947 team won the AL pennant and defeated the Dodgers in a seven-game World Series.[133] After the end of the Series, MacPhail sold his share of Yankees ownership to Topping and Webb for $2 million.[134]

1948–1956: Stengel hire and five straight World Series wins

Despite contending late into the season, the 1948 Yankees finished in third place. Harris was released and the Yankees brought in Casey Stengel to manage.[135] At the time, Stengel had "a reputation as a bit of a clown", according to Appel, and had been unsuccessful in two previous MLB managing stints.[136] As the Yankees' manager, he optimized matchups by using a platoon system, playing more left-handed batters against right-handed pitchers.[137] Numerous injuries affected the team[138] during the 1949 season but it battled with the Red Sox for the AL pennant; before a season-ending two-game series at Yankee Stadium, New York trailed Boston by one game and needed a pair of wins.[139] By scores of 5–4 and 5–3, the Yankees won the two games and the league championship.[140] New York won a World Series rematch with the Dodgers in five games.[141] Stengel was named AL Manager of the Year in his first season.[138] The Yankees faced another competitive pennant race in 1950, as the Tigers joined New York and Boston at the top of the AL. Late in the season, the Yankees broke a tie with the Tigers for first place and went on to win the pennant.[142] In the 1950 World Series, the Yankees swept the Phillies; the second game was decided by a DiMaggio home run in the tenth inning.[143] Following the season, Yankee Phil Rizzuto was named AL MVP after recording 200 base hits during the regular season.[144]

Fan interest in attending games had begun declining throughout MLB in the late-1940s, and the Yankees faced a drop-off in their crowds after 1947, when they sold about 2.2 million tickets. By 1957, season attendance was down by over 700,000.[145] New York baseball fans had the option of watching games on television instead by the early 1950s. The Yankees joined the other New York City franchises in allowing game telecasts. This was a departure from the team's strategy when radio broadcasts were introduced.[146] Regular season games of the Yankees were not broadcast until 1939, as management believed that fewer fans would attend games if they could listen on radios.[147]

DiMaggio played his final MLB season in 1951, while highly touted outfielder Mickey Mantle made his debut for New York. Pitcher Allie Reynolds threw two no-hitters during 1951, as the Yankees claimed the AL pennant for the third straight year. They then won the 1951 World Series against the Giants, four games to two.[148] When their 1952 team took the AL pennant, the Yankees had an opportunity to match the four straight World Series championships won by the team from 1936 to 1939. In another Yankees–Dodgers matchup, New York fell behind three games to two, but victories in games six and seven gave the Yankees the title.[149] New York and Brooklyn were matched again in the 1953 World Series, and a Billy Martin base hit that decided the sixth and final game of the Series gave the Yankees another four games to two victory and a fifth title in a row.[150] As of 2021, the 1949–1953 Yankees are the only MLB teams to win five straight World Series; no team since has won more than three in a row.[151]

The Yankees won 103 games in 1954, the most yet for a Stengel-managed team, but the Indians took the pennant with a then-AL record 111 wins.[152] One year later, the 1955 Yankees faced the Dodgers in the World Series.2002 After the teams split the first six games of the Series, the Yankees lost the seventh and final game 2–0, giving the Dodgers their first Series win.[153] Elston Howard, the first African American player in Yankees history, made his debut in 1955. His arrival came eight years after MLB's color line had been broken, as the Yankees' management had sought to avoid integrating the club's roster.[154] As teams such as the Dodgers added black players, the Yankees turned down numerous opportunities to acquire Negro league talent.[155] Management feared alienating white fans and harbored stereotypes of African American players. Author Robert Cohen called these views "symbolic of the overall arrogance of Yankee ownership and management, as well as their prevailing racial attitudes."[156]

In 1956, Mantle won the MVP award for a season in which he led the AL and MLB in batting average (.353), home runs (52), and RBIs (130), becoming the second Yankee (after Gehrig in 1934) to win a Triple Crown.[157] The 1956 Yankees won the franchise's seventh AL championship under Stengel and advanced to a World Series rematch with the Dodgers. In Game 5, with the Series even at 2–2, Yankees pitcher Don Larsen threw a perfect game. In seven games, the Yankees won the Series.[158]

1957–1964: Continued success

By 1957, the Yankees had won 15 of the last 21 AL pennants. The team's minor-league system had been reduced to 10 teams from a peak of 22, and its scouting system was acclaimed by Sports Illustrated's Roy Terrell as "the best in all baseball."[159] Instead of signing many players for their organization, the Yankees concentrated on acquiring a smaller number of highly skilled players, according to head scout Paul Krichell. The club recruited players by selling them on the "fame, fortune and fat shares of a World Series pot" that came with making New York's roster.[159]

The 1957 Yankees reached that year's World Series, but lost in seven games to the Milwaukee Braves.[160] Following the Series, the Giants and Dodgers left New York City for California, leaving the Yankees as New York's only MLB team. Despite their status as the sole New York City-based franchise, the Yankees' 1958 attendance decreased from previous seasons as the team could not attract bereft Giants and Dodgers fans.[161] In the 1958 World Series, the Yankees had an opportunity to avenge their defeat to the Braves. The Yankees fell behind by losing three of the first four games, but won the final three games of the Series to claim another championship.[162] The Yankees were unable to defend their AL and World Series championships in 1959, as they ended up with a 79–75 record, their worst record since 1925, good for third place.[163]

When Arnold Johnson (a friend of Topping and Yankees general manager George Weiss) became the owner of the Kansas City Athletics in 1955, his new team made many transactions with the Yankees. From 1956 to 1960, the Athletics traded many young players to the Yankees for cash and aging veterans. The trades strengthened the Yankees' roster, but brought criticism from rival clubs.[164] Before their 1960 season, the Yankees made one such trade with the Athletics in which they acquired outfielder Roger Maris.[165] In his first Yankees season, Maris led the league in slugging percentage, RBIs, and extra base hits, finished second with 39 home runs, and won the AL MVP Award.[166] The 1960 Yankees won the AL pennant for the 10th time in 12 years under Stengel, and outscored the Pirates 55–27 in the seven World Series games. However, the team lost four of them, falling short of a Series championship after Bill Mazeroski hit a walk-off home run in the final game, ending a contest that Appel called "one of the most memorable in baseball history."[167] The season turned out to be Stengel's last as Yankees manager; he indicated that his age played a role in the team's decision, saying, "I'll never make the mistake of being seventy again."[168]

Ralph Houk was chosen to replace Stengel.[169] During the 1961 season, both Mantle and Maris chased Ruth's single-season home run record of 60, and the pair attracted much press attention as the year progressed. Ultimately, an infection forced Mantle to leave the lineup and bow out of the race in mid-September with 54 home runs. Maris continued, though, and on October 1, the final day of the season, he homered against Red Sox pitcher Tracy Stallard into the right field stands of Yankee Stadium, breaking the record with 61. Commissioner Ford Frick decreed that two separate records be kept, as the Yankees played a 154-game schedule in 1927 (beginning in 1961, AL teams played 162 games to accommodate the league's expansion to 10 teams).[170][171] MLB did away with the dual records 30 years later, giving Maris sole possession of the single-season home run record before it was broken in 1998 by Mark McGwire.[172] The Yankees won the pennant with 109 regular season wins, at the time the club's second-highest single-season total, and defeated the Cincinnati Reds in five games to win the franchise's 19th World Series. The team hit 240 home runs to break the MLB single-season record. Maris won another AL MVP Award, while Whitey Ford captured the Cy Young Award, having posted a 25–4 record. The team gained a reputation as one of the strongest the Yankees had fielded, along with the 1927 and 1939 Yankees.[173] New York returned to the World Series in 1962, facing the San Francisco Giants. After exchanging victories in the first six games of the Series, the Yankees won the decisive seventh game 1–0 to clinch the title.[174]

The Yankees again reached the World Series in their 1963 campaign, but were swept in four games by the Los Angeles Dodgers. Houk left the manager's position to become the team's general manager and the newly retired Berra was named manager.[175] After dealing with player injuries and internal dissension, the Yankees rallied from third place late in the 1964 season and won the AL pennant by one game over the White Sox.[176] It was their fifth straight World Series appearance and 14th in the past 16 years.[151] The team faced the St. Louis Cardinals in a series that included a walk-off home run by Mantle to end the third game. Despite Mantle's game-winning hit, the Yankees were defeated by the Cardinals in seven games, and Berra was fired.[177]

1965–1972: New ownership and decline

In 1964, CBS announced that it was purchasing 80 percent of the Yankees for $11.2 million. The television network bought the remaining 20 percent, originally retained by Topping and Webb, during the next two years. Topping left as team president after the sale; CBS executive Mike Burke replaced him.[178] From 1962 to the sale, Topping and Webb had sharply curtailed the Yankees' investment in their minor league system, to show greater profits. As a result, the team lacked capable replacements for its aging players.[179] Other factors affected the club's fortunes as well. The team had been slow in signing African American players even after Howard,[180] and lost the opportunity to sign future stars.[181] As most American League clubs dragged their feet in integrating their rosters, the rapid decline of the Yankees' white stars left them on the same footing as the rest of the league.[182] Also, the 1965 introduction of the MLB draft, which allowed the clubs with the worst records to have the first selections, meant that the Yankees could not outbid other teams for young talent.[183] Their trade pipeline with the A's had dried up by 1960, as new A's owner Charlie Finley announced his intention to avoid trading with New York.[184] Competition for the attention of local fans had been provided by the expansion New York Mets, founded in 1962. By 1964, the new club started a 12-year streak of outdrawing the Yankees; the Mets also won the 1969 World Series.[185]

The Yankees had a record of 77–85 in 1965, and their sixth-place finish was their lowest since 1925. It was only their second finish in the second division since 1918. Johnny Keane, who was hired to succeed Berra as manager, was fired after the Yankees lost 16 of 20 games to start their 1966 season; Houk named himself as Keane's replacement. A last-place finish—their first since 1912—followed at season's end, and the Yankees ended up one position higher, ninth, the following season. Ford, Howard, Mantle, and Maris all retired or were traded to other clubs between 1966 and 1969.[186] Attendance at Yankee Stadium fell to between 1 and 1.3 million fans per season from 1965 to 1971, and dropped below 1 million in 1972.[187] One 1966 game had a crowd of 413 fans; television announcer Red Barber was fired by the Yankees after discussing the low attendance during his telecast.[188]

After fifth-place finishes in 1968 and 1969 (the latter in the newly created six-team American League East division), the 1970 Yankees improved to second in the AL East with a 93–69 record,[189][190] finishing behind the Baltimore Orioles.[191] Catcher Thurman Munson played his first full season for the Yankees and won AL Rookie of the Year honors for 1970.[192] New York had 11 more losses during their 1971 season than they had in 1970,[193] but in 1972 they contended for the AL East title and a playoff berth. Late in the season, the Yankees were in a four-way tie for the most wins in the division, but a slump caused them to fall to fourth by the end of their campaign with a record of 79–76.[194]

1973–1976: Steinbrenner takes over

Less than a decade into its ownership of the Yankees, CBS moved to sell the team in 1972. In eight years, the team posted an $11 million loss under CBS,[195] losing money in all but two years.[196] Along with the decrease in attendance, the Yankees' television revenues fell by more than 80 percent from their peak, and in 1973 were more than $1 million below what the Mets earned from their broadcasting agreement.[197] A group of investors, led by Cleveland-based shipbuilder George Steinbrenner, purchased the club from CBS on January 3, 1973 for $10 million.[198] Despite an initial promise that he would "stick to building ships" and remain in the background, Steinbrenner proved to be a hands-on owner, clashing with Burke and forcing him out of his leadership position.[199] Describing the level of control displayed by the lead owner, investor John McMullen stated, "There is nothing in life quite so limited as being a limited partner of George Steinbrenner."[200]

The 1973 Yankees held the AL East lead entering August, but faded and ended the year fourth.[201] The 1973 season was the team's last in Yankee Stadium before the building was renovated.[202] The Yankees had become concerned about the drop in attendance and the poor conditions of the stadium's surroundings. For a time, New Jersey sought to attract sports teams to the Meadowlands Sports Complex, and New York City acted to prevent the Yankees from moving. The city paid $24 million to buy Yankee Stadium and the adjacent land, and in 1972 agreed to renovations.[203] Work on the stadium finished in 1976, and the Yankees were required to play at the Mets' home field, Shea Stadium, in 1974 and 1975.[204] During the first of those seasons, the team nearly won the AL East, finishing behind the Orioles in a race that was decided in the final games. The Yankees were helped by an early-season trade that brought first baseman Chris Chambliss to the team, and improved to 89 wins from 1973's 80 victories.[204]

After the 1974 season, star pitcher Catfish Hunter was declared a free agent because of a skipped insurance payment.[205] The Yankees signed him to a $3.75 million, four-year contract. It was the beginning of a long-term franchise philosophy of using free agency to acquire talent; Stout writes that they "were the first team to comprehend what free agency meant", as it provided an advantage over lower-spending rivals and generated fan and media interest.[206] Hunter had 23 wins during the Yankees' 1975 season, but the team did not contend for the playoffs after July.[206] New York fired manager Bill Virdon in August and hired Billy Martin as his replacement.[207] With Martin as the helm, the Yankees returned to the postseason in their first season in the renovated Yankee Stadium, winning the 1976 AL East title by a 10+1⁄2-game margin over the Orioles. Munson was named AL MVP, with a .302 batting average and a total of 105 RBIs that was second-best in the AL. The 1976 American League Championship Series (ALCS) between the Yankees and Kansas City Royals went to a deciding fifth game, which was won by New York on a walk-off home run by Chambliss. The Yankees did not win a game against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1976 World Series.[208]

Free agency era

1977–1981: "The Bronx Zoo"

Free agency was introduced more fully from the 1976 offseason; outfielder Reggie Jackson, who had spent one season with the Orioles after being traded by the Athletics, was the most significant player available in that first offseason.[209] Steinbrenner signed Jackson to a five-year, $2.96 million contract, giving the Yankees a key player, but one who had difficulty fitting in with the rest of the team. Martin had opposed Jackson's signing, and many players were angered by comments Jackson made that were critical of Munson. Jackson and Martin nearly came to blows in the Yankees' dugout during one game against the Red Sox, in which Martin removed Jackson for being slow to field a ball. The incident sparked media reports of disputes between Martin and Steinbrenner, and further conflict between Martin and Jackson. The Yankees of the late-1970s, noted for clubhouse conflict and on-field success, were later nicknamed "The Bronx Zoo", after a book of the same name by pitcher Sparky Lyle, and at the time, New York and the baseball world were agog at their antics.[210] The 1977 Yankees won the AL East and defeated the Royals in the 1977 ALCS. Trailing 3–2 in the top of the ninth inning of the decisive fifth game, the Yankees scored three times to gain a berth in the World Series.[211] Against the Dodgers, the Yankees prevailed in six games for their first Series championship since 1962. Jackson hit a record five home runs in the Series, including three in Game 6 on consecutive pitches, against three different Dodgers pitchers.[212] Jackson gained his own candy bar and the nickname "Mr. October".[213]

Before their 1978 season, the Yankees added relief pitcher Goose Gossage, even though their closer was reigning Cy Young Award winner Lyle.[214] By the middle of July, the team was 14 games behind the Red Sox and infighting had begun again. After making comments to reporters criticizing both Jackson and Steinbrenner, Martin resigned and Bob Lemon was hired as manager. The Yankees closed the gap that Boston had opened on them, and by the start of a four-game series at Fenway Park on September 7, the Red Sox' lead was down to four games.[215] Over the course of the series, nicknamed "The Boston Massacre", the Yankees outscored the Red Sox 42–9, winning each game.[216] The teams finished the regular season with identical records, and an AL East tie-breaker game was held on October 2.[217] Losing 2–0 in the seventh inning, the Yankees took the lead on a three-run home run by shortstop Bucky Dent, and eventually won 5–4.[218] After beating the Kansas City Royals for the third consecutive year in the ALCS, the Yankees faced the Dodgers again in the 1978 World Series. They lost the first two games on the road, but then returned to Yankee Stadium and won three consecutive games before clinching a Series championship in Game 6 in Los Angeles.[219] Pitcher Ron Guidry was the Cy Young Award winner in 1978, having posted 25 wins against 3 losses with a 1.74 ERA, and 248 strikeouts. Eighteen of his strikeouts came in his June 17 appearance against the California Angels, which broke the franchise record.[220]

On August 2, 1979, Munson was killed in a plane crash. Martin, who had returned as manager after Steinbrenner fired Lemon in June, said that with his death, "The whole bottom fell out of the team."[221] The 1979 Yankees finished fourth with an 89–71 record.[222] Steinbrenner fired Martin after the season and replaced him with Dick Howser, who led the Yankees to 103 wins and the AL East title in 1980. Jackson led the AL with 41 home runs and posted a .300 batting average for the Yankees, who finished three games ahead of the Orioles. Their stay in the postseason was brief, as the Royals beat them in three straight games to win the ALCS.[223] Before their 1981 campaign, the Yankees signed Dave Winfield to a 10-year contract worth $23 million, a record at the time. The season was shortened by a strike, and the Yankees qualified for the playoffs by virtue of leading the AL East when the work stoppage began. They defeated the Milwaukee Brewers in a divisional playoff round in five games. and won the AL pennant with three straight wins over the Athletics in the ALCS. The Yankees won the first two games of the 1981 World Series against Los Angeles, but the Dodgers won the next four games and the championship.[224]

1982–1995: Struggles and return to postseason

Following the team's loss to the Dodgers in the 1981 World Series, the Yankees had a 15-year absence from the World Series, the longest since the time before their initial appearance in 1921.[225] As the 1980s progressed, the Yankees regularly spent heavily on free agents who were often aging and proved to be declining in performance.[226] The atmosphere of turmoil around the club discouraged some players from signing contracts with New York; they either ignored the Yankees' offers or used them to get more money from other teams.[227] Steinbrenner traded prospects for veterans; sportswriter Buster Olney called this "a practice that ultimately inflicted serious damage on the organization, leaving the team without the needed influx of young and cheap talent."[228] With Steinbrenner at the helm, the team continued to change managers frequently; there were 21 managerial changes in his first two decades of ownership; Martin served five separate stints as New York's manager.[229]

The 1982 and 1983 Yankees were fifth and third, respectively.[230] Henry Fetter wrote of the following year's team, which had several aging players, "The 1984 Yanks had assembled an all-star lineup—but it was that of 1979."[226] In what became a trend in future seasons, the Yankees lacked effective pitching, undoing the efforts of a top-tier offense that included players such as Winfield and first baseman Don Mattingly, one of the few star hitters produced by the farm system during the era. Mattingly led the AL in batting average in 1984—beating out Winfield for the league lead.[231] The Yankees' 1985 season began with a batting lineup improved by an offseason trade for Rickey Henderson, the future MLB career stolen base and runs scored record holder.[232] Mattingly was AL MVP in 1985, with 145 RBI and a personal-best 35 home runs, while Guidry won 22 games. The Yankees had 97 wins, two off the division leader Toronto Blue Jays.[233] The 1986 side's win total fell to 92, but it was only enough for second place again behind Boston. Mattingly hit an MLB record six grand slam home runs in 1987, but dealt with back pain that limited his effectiveness in his remaining years. The Yankees fell to fourth,[234] beginning a six-year streak of fourth or worse.[235] The Yankees had the most wins of any MLB team during the 1980s,[236] but missed the playoffs eight times during the decade and did not win a World Series.[237] Many New York baseball fans chose to support an exciting Mets team. From 1984 to 1992, a period that featured their 1986 World Series victory, the Mets' attendance topped that of the Yankees every year.[226] Despite falling attendance, the Yankees' finances were not significantly harmed, as they had a 12-year television rights contract with the Madison Square Garden network that gave them a record $500 million and flexibility to increase their payroll if desired.[238]

Winfield's tenure with the team ended when he was traded in May 1990. The 1990 team lost 95 games to finish at the bottom of the AL East, and its .414 winning percentage was the franchise's worst since 1913.[239] The Yankees underwent a dramatic change in their front office that year, which Glenn Stout cites as a turning point for the club.[240] Winfield had become a target of Steinbrenner in previous years. At one 1985 game, he criticized Winfield by calling him "Mr. May", that is, a player who only performed well early in the season.[240][241] Steinbrenner also resented Winfield's salary as too high, and was critical of a charitable foundation run by him.[240] A gambler was paid by Steinbrenner "for damaging information" about Winfield,[242] an incident that resulted in an indefinite ban from then-commissioner Fay Vincent in 1990; three years later, Steinbrenner was reinstated.[243] Under new general manager Gene Michael, the Yankees allowed their minor league talent more time to improve their skills and more of a chance to play for the Yankees if they were good enough.[244] Michael focused on on-base percentage in deciding which hitters to pursue, and emphasized left-handed batters who might take advantage of Yankee Stadium's short right-field porch.[245] The players developed by the team during its rebuilding years included outfielder Bernie Williams, a future AL batting average leader,[246] and a group—Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada, and Mariano Rivera—that became the centerpiece during the 1996–2000 period, and was later nicknamed the "Core Four".[247]

After a 71-win 1991 season, the Yankees replaced their incumbent manager, Stump Merrill, with Buck Showalter, who increased the playing time given to young players. While the 1992 Yankees were 20 games behind the AL East winner, offseason acquisitions—third baseman Wade Boggs, pitcher Jimmy Key, and outfielder Paul O'Neill—helped the 1993 team to an 88–74 record and New York's highest finish (second) in seven seasons. By 1994, the Yankees had progressed to the point where they led the AL with a 70–43 record going into the homestretch of the regular season.[248] Their campaign was cut short by a players' strike, which resulted in the cancellation of the playoffs and 1994 World Series.[249] Many media members believed that the Yankees might have reached the World Series if not for the strike.[250] A year later, the team reached the playoffs and gave Mattingly his first career postseason appearance by winning the first AL wild card berth, but it was eliminated in a five-game Division Series (ALDS) against the Seattle Mariners.[251]

1996–2001: Championship run

Mattingly did not return to the Yankees for their 1996 season, and the club replaced Showalter with Joe Torre.[252] Although the managerial change met with a mixed reception by the press,[253] Torre received praise for his handling of players as his managerial career progressed; Olney remarked that he was able to "defuse powder-keg issues and serve as a buffer between Steinbrenner and the players."[254] Jeter won the AL Rookie of the Year Award in his first full season with the Yankees, and Pettitte with 21 wins was second in AL Cy Young Award voting and Rivera posted an 8–3 record and 2.09 ERA as the club won a division title.[255] New York reached the 1996 World Series, where they lost the first two games at home to the Atlanta Braves by a combined score of 16–1. But New York won three straight contests in Atlanta, including a Game 4 in which they scored eight straight runs to rally from a 6–0 deficit.[256] With a 3–2 win in Game 6, the Yankees won the World Series for the first time in 18 years.[257] For 1997, the Yankees signed starting pitcher David Wells and allowed closer John Wetteland to leave in free agency, enabling Rivera to inherit the role. The 1997 Yankees earned a wild card playoff berth, but lost three games to two against the Cleveland Indians in the ALDS.[258]

In preparation for their 1998 season, the Yankees replaced general manager Bob Watson with Brian Cashman. The club made many player acquisitions, gaining the services of third baseman Scott Brosius, second baseman Chuck Knoblauch, and starting pitcher Orlando Hernández. The Yankees won 28 of their first 37 games—a stretch that concluded with a perfect game pitched by Wells—and by August were 76–27.[259] The 1998 Yankees are considered by some writers to be among the greatest teams in baseball history,[260][261][262] having compiled a then-AL record of 114 regular-season wins against 48 losses. After playoff series wins over the Texas Rangers and Indians, New York defeated the San Diego Padres in four consecutive World Series games for their 24th Series title.[263]

After the 1998 season, Wells was traded to the Toronto Blue Jays for Roger Clemens, who had just completed two consecutive Cy Young Award-winning seasons. In a regular season that included another perfect game by a Yankees pitcher, this one by David Cone, New York led the AL East with 98 wins and beat the Rangers in the ALDS. This led to an ALCS against the rival Red Sox. New York won the first two games en route to a 4–1 series win, and went on to sweep the Braves in the 1999 World Series. The postseason results gave the 1998–99 Yankees a 22–3 playoff record, and the team held a 12-game winning streak in World Series competition dating back to 1996.[264] Although the 2000 Yankees had an 87–74 regular season record that was the worst among playoff qualifiers and lost 15 of their last 18 games,[265] the team won consecutive playoff series to claim the AL championship. New York's pennant placed them in the 2000 World Series against the cross-town Mets, the first Subway Series in 44 years.[266] With a four games to one victory, the Yankees gained their third successive title.[267] As of 2020, the 2000 Yankees are the most recent MLB team to repeat as World Series champions and the Yankees of 1998–2000 are the last team to win three consecutive World Series.[151]

Free agent pitcher Mike Mussina signed with the Yankees before their 2001 season began, and the club pulled away from the Red Sox as the year progressed to claim another divisional championship, as Clemens won 20 games. The September 11 attacks interrupted the season, and the resumption of baseball in New York became a symbol of how the city recovered from the destruction of the Twin Towers. After falling behind 2–0 in the ALDS against the Athletics, the Yankees won three straight contests to advance to the ALCS. They prevailed in five games against the Seattle Mariners, who had tied a single-season MLB record with 116 regular season wins, for the team's fourth straight AL pennant.[268] The Arizona Diamondbacks gained a two-game lead in the 2001 World Series before the Yankees won three consecutive ballgames; New York home runs with two outs in the ninth inning of Games 4 and 5 led to extra inning wins in both games, with Game 4 ended by a Jeter home run.[269] The Yankees' championship streak ended, though, as the Diamondbacks won the Series in seven games with a late rally in the final inning of Game 7.[270]

2002–2008: Final years in old Yankee Stadium

After the 2001 season, several players from the late 1990s and early 2000s Yankees teams departed. New York won their fifth AL East title in a row in its 2002 campaign, but the Anaheim Angels defeated the Yankees in the ALDS.[271] The Yankees' major acquisition in the offseason was leading Japanese hitter Hideki Matsui of the Yomiuri Giants.[272] Another signing, that of Cuban pitcher José Contreras, led to complaints from Red Sox CEO Larry Lucchino, who dubbed his team's rivals "the Evil Empire".[273] Tensions between the rivals increased in the coming seasons, and writers called the rivalry one of the most intense and well known in North American professional sports.[274][275][276] By 2003, New York's overall payroll had reached almost $153 million, more than the Padres, Brewers, Royals, and Tampa Bay Devil Rays combined.[277] Criticism of the Yankees' spending such as Lucchino's was frequently raised; during a 15-year stretch from 1999 to 2013, they had the biggest MLB player payroll every year.[278]

Jeter became the Yankees' captain in their 2003 season. The team faced the Red Sox in the ALCS. The series came down to a seventh game, and the Yankees fell behind before three eighth-inning runs forced a 5–5 tie and extra innings. Aaron Boone, a third baseman acquired by New York in a mid-season trade, hit a walk-off home run in the 11th inning to give New York the pennant. The Yankees were then defeated by the Florida Marlins in the World Series, four games to two.[279] The Yankees added power hitting to their lineup in the offseason, signing free agent Gary Sheffield and trading for shortstop Alex Rodriguez, who became a third baseman with New York. Three of the starting pitchers from the previous season—Clemens, Pettitte, and Wells—left the team before the season. Despite the losses, the 2004 Yankees managed to top the AL East with 101 wins and defeat the Twins three games to one in the ALDS.[280] The victory set up an ALCS rematch with the Red Sox. The Yankees took a 3–0 series lead before losing four consecutive games, becoming the first team in MLB history to lose a best-of-seven series after winning the first three games.[281]

The 2005 season featured an AL MVP performance by Rodriguez, who hit a league-leading 48 home runs with 130 RBIs and a .321 batting average. The Yankees beat the Red Sox for the division title because they won 10 of their 19 contests against Boston; both teams had 95–67 records.[282] The Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim defeated the Yankees in five games in the first round of the postseason.[283] The 2006 Yankees kept at the same level, as they won the AL East for the ninth straight year but were eliminated in the ALDS by the Detroit Tigers three games to one.[283]

Rodriguez again won the AL MVP award in 2007, as his 54 home runs and 156 RBIs topped the AL; he scored 143 runs, the highest single-season number by a player since 1985. After starting the year 21–29, the Yankees rallied to win the AL's wild card berth; it was the first time in 10 seasons that they did not win the AL East. New York's season ended in the first round of the playoffs; the Indians won the opening two games of the ALDS and finished the series in four games. Manager Torre did not re-sign after the season, and Joe Girardi took his place.[284] Rodriguez, who used an opt-out clause in his contract to become a free agent, stayed with the Yankees by signing for $275 million over 10 seasons, an MLB record.[285] The 2008 season was the Yankees' last in which they played at the original Yankee Stadium. The club had sought a new stadium to increase revenues, following the example set by other MLB teams.[286] It was also the first in which Hal and Hank Steinbrenner ran the team as general partners; though George Steinbrenner was still the principal owner on paper, he yielded operational responsibilities during the 2007 offseason. Yankee Stadium was the site of the 2008 All-Star Game, but for the first time in 14 years did not host playoff action. New York ended the year third in the AL East and failed to qualify for the postseason.[287]

2009–2016: New stadium and record 27th championship

The new Yankee Stadium, which cost a record $1.5 billion, was constructed near the old facility. As built, it had a capacity of approximately 52,000, with 52 luxury suites.[286] Monument Park, which holds plaques and monuments honoring former Yankees personnel, was built beyond the center field fence; its collection was transplanted from the old stadium.[288] For the 2009 season, the team committed over $400 million in future salaries to three free agents: pitchers CC Sabathia and A. J. Burnett, and first baseman Mark Teixeira.[289] New York won 90 of its last 134 games, and broke the franchise single-season record by hitting 244 home runs.[290] Another club record was broken by Jeter, who passed Gehrig as the Yankees' all-time hits leader on September 11.[291] New York posted 103 wins in 2009 and beat out the Red Sox for the division title by eight games. In the AL playoffs, the Yankees defeated the Twins in the ALDS and the Angels in the ALCS, advancing to the World Series. There, they faced the defending Series champions, the Philadelphia Phillies.[292] Behind a six-RBI effort by Matsui in the sixth and final game, the Yankees defeated the Phillies to win their record 27th Series championship.[293]

George Steinbrenner died in July 2010. The Yankees won the league's wild card berth, but their title defense was ended by the Texas Rangers in the ALCS.[294] Multiple Yankees players set individual marks in 2011. Jeter joined the 3,000 hit club on July 9; he was the first player to do so while playing for the club. Later in the season, Rivera posted the 602nd save of his career, breaking the all-time record that had been held by Trevor Hoffman. The Yankees won the AL East, but lost in the ALDS to the Tigers.[295] Rivera suffered a season-ending injury to his right knee in May 2012 while catching fly balls before a game against the Royals.[296] Even without their longtime closer, the 2012 Yankees gained a 10-game lead by mid-July, and held off the Orioles to win the division title by a final margin of two games.[297] After defeating the Orioles in a five-game ALDS, the Yankees were swept by the Tigers in the ALCS.[298]

During Game 1 of the 2012 ALCS, Jeter broke his right ankle while attempting to field a ball.[299] He was one of many Yankees to miss playing time during the club's 2013 campaign; 20 players were placed on the disabled list at least once. The team had an opportunity to win a wild-card playoff spot, but faded late in the season.[300] It was only the second time since 1995 that New York did not qualify for postseason play.[301] In the offseason, second baseman Robinson Canó departed New York for the Mariners in free agency, but the Yankees signed starting pitcher Masahiro Tanaka, who was coming off a 24–0 year with Japan's Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles, to a seven-year contract.[302] Rodriguez was suspended for the 2014 season by MLB for using performance-enhancing drugs.[303] The 2014 Yankees, the last with Jeter in their lineup, fell four games short of a postseason berth with an 84–78 record. Despite signing several new hitters prior to the season, the team finished third from last in the AL in runs scored.[304] The offense improved in 2015, ending the regular season with the second-most runs in MLB. New York gained a wild card berth with a second-place finish, but was defeated by the Houston Astros in a one-game playoff.[305] The Yankees traded several veteran players during their 2016 season and received Gleyber Torres, among others, in return.[306][307] In August 2016, Rodriguez was released from his contract.[308] The club had 84 wins, but missed the playoffs for the third time in four years.[306] As the Yankees' on-field performance declined after 2009, their attendance and television ratings fell;[309][310] revenue from ticket and luxury suite sales at Yankee Stadium decreased by more than 40 percent from 2009 to 2016.[311]

2017–present: Rise of the "Baby Bombers"

The 2017 Yankees featured a group of young players who became known as the "Baby Bombers".[312] Among them were outfielder Aaron Judge, catcher Gary Sánchez, starting pitcher Luis Severino, and first baseman Greg Bird.[313] Judge hit a league-leading 52 home runs, the most ever by a rookie;[314] he was the AL MVP runner-up and won AL Rookie of the Year honors.[315] The infusion of talent led to both renewed fan interest and improved play.[316] New York earned a postseason berth and reached the ALDS by beating the Twins in the AL wild card game. The Indians gained a two-game lead in the ALDS, but the Yankees won three consecutive times to advance to the ALCS. Against the Astros, the Yankees lost in seven games.[314] After 10 years as the team's manager, Girardi was replaced by Boone.[317] New York acquired outfielder Giancarlo Stanton, the 2017 NL MVP, in an offseason trade with the Marlins.[318] Stanton had 38 of the 267 home runs hit by the Yankees in 2018, as the club set an MLB single-season record.[319] They again qualified for the playoffs and made it to the ALDS, where they faced the Red Sox. The Yankees were defeated three games to one by their rivals, falling short of a return to the ALCS.[320]

In 2019, the Yankees won 103 games and the AL East championship.[321] The team hit 306 home runs, surpassing the previous season's record and finishing second in MLB behind the Twins, their opponents in the ALDS.[322] After sweeping Minnesota,[321] New York had another ALCS matchup with Houston. A walk-off home run by José Altuve in the sixth game gave the Astros their third playoff elimination of the Yankees in five years. The 2010s was the first calendar decade since the 1910s in which the Yankees did not win a pennant.[323] Before the 2020 season, which was shortened to 60 games by the COVID-19 pandemic,[324] the team sought to bolster its starting pitching by signing Gerrit Cole to a $324 million contract.[325] The Yankees qualified for their fourth consecutive postseason,[324] but were defeated by the Tampa Bay Rays in the ALDS.[325] The 2021 Yankees earned a wild card playoff berth with a 92-win season and made the franchise's 57th playoff appearance, losing the AL wild card game 6–2 to the Red Sox.[326]

In 2022, the Yankees had an extremely strong start, entering July with a 56–21 record and being on pace to break the all-time single-season wins record by an MLB team. They went a mediocre 43–42 the rest of the way, but the Yankees managed to win their division and the second seed in the American League. Aaron Judge hit 62 home runs, breaking the 61-year-old American League single-season record held by Roger Maris. After defeating the Cleveland Guardians in the Division Series in five games, the Yankees fell to the Houston Astros in the Championship Series in a four-game sweep, the first sweep in a best-of-seven series since the 2012 American League Championship Series.

Notes

- The Yankees do not count the Orioles years as part of their history. Baseball-Reference.com included the 1901 and 1902 Orioles in its statistics for the Yankees until 2014, when it decided to separate the two years from the subsequent New York-based seasons. Official MLB historian John Thorn supported the change, citing the new ownership, high roster turnover, and AL takeover of the Orioles.[16] Appel wrote that "many historians feel the Yankees and the Orioles were the same franchise", and called the background of the modern club "a question of historical debate"; he opined that "There seems little to really connect the two teams other than one replacing the other."[17]

References

- "Major League Teams and Baseball Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Huffman, Joshua (May 24, 2011). "Sports Franchises With the Most Championships in North America". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "New York Yankees Hall of Fame Register". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- Grott, Connor (April 9, 2020). "Forbes: New York Yankees Most Valuable MLB Franchise at $5 Billion". United Press International. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Stout 2002, p. 455.

- Tygiel 2000, pp. 48–49.

- Tygiel 2000, pp. 47, 49.

- "1901 Baltimore Orioles". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- Tygiel 2000, p. 52.

- Fetter 2005, p. 22.

- Fetter 2005, pp. 22–23.

- Appel 2012, p. 5.

- Fetter 2005, p. 23.

- Stout 2002, pp. 9–14.

- Appel 2012, p. 13.

- Zalman, Jonathan (August 15, 2014). "The Yankees' Missing Chapter". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- Appel 2012, pp. 13–14.

- Fetter 2005, pp. 204–205.

- Appel 2012, pp. 16–18.

- Appel 2012, p. 18.

- Stout 2002, pp. 16–21.

- "Statistics". Major League Baseball. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- Stout 2002, pp. 27–39.

- Stout 2002, pp. 41–43.

- Stout 2002, pp. 44–46.

- Appel 2012, p. 45.

- Reisler 2005, p. 260.

- Stout 2002, pp. 47–49.

- Appel 2012, pp. 53–55.

- Stout 2002, p. 57.

- Appel 2012, pp. 58–59.

- Stout 2002, p. 59.

- Appel 2012, p. 61.

- Reisler 2005, p. 101.

- Stout 2002, pp. 58–59.

- Appel 2012, p. 62.

- Appel 2012, p. 63.

- Stout 2002, p. 60.

- Stout 2002, pp. 18–19, 59.

- Worth 2013, p. 203.

- Appel 2012, p. 67.

- Wiggins 2009, p. 133.

- Appel 2012, pp. 66–69.

- Pepe 1998, pp. 17, 19.

- Haupert & Winter 2003, p. 92.

- Gallagher 2003, p. 318.

- Stout 2002, p. 68.

- Appel 2012, pp. 32–33.

- "Yanks to Change Jerseys to Honor Fenway". Fox Sports. April 18, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- Stout 2002, pp. 68–69.

- Stout 2002, p. 70.

- Appel 2012, pp. 84–85.

- Stout 2002, pp. 70–72.

- Stout 2002, pp. 73–76.

- Appel 2012, pp. 90–92.

- "1919 New York Yankees". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- Fetter 2005, pp. 69–72.

- Fetter 2005, p. 75.

- Stout 2002, pp. 81–83, 87.

- "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Home Runs". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Stout 2002, p. 83.

- Appel 2012, p. 97.

- Stout, Glenn (July 18, 2002). "When the Yankees Nearly Moved to Boston". ESPN. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- Appel 2012, p. 95.

- Appel 2012, p. 182.

- "New York Yankees Top 10 Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Appel 2012, pp. 94–95, 182.

- Appel 2012, p. 100.

- Stout 2002, pp. 86–87.

- Haupert & Winter 2003, pp. 94–96.

- Appel 2012, p. 106.

- Stout 2002, pp. 91–92.

- Stout 2002, pp. 93–96.

- Appel 2012, p. 108.

- Worth 2013, p. 206.

- Appel 2012, pp. 112–113.

- Pepe 1998, p. 27.

- Appel 2012, p. 118.

- Stout 2002, pp. 102–103.

- Fetter 2005, pp. 75, 78–79.

- Stout 2002, p. 91.

- Harper, John (April 15, 2003). "A Real Home Opener: Classic Moment 10 – April 18, 1923". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- Fetter 2005, pp. 79–81.

- Stout 2002, pp. 96–97.

- Carino 2004, p. 52.

- Stout 2002, pp. 97, 103–105.

- Axisa, Mike (January 5, 2015). "Happy 95th Anniversary: Red Sox Complete Sale of Babe Ruth to Yankees". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Stout 2002, pp. 105–108.

- Haupert & Winter 2003, p. 93.

- Stout 2002, pp. 111–113.

- Rivera, Marly (September 20, 2020). "'Enjoy It While It Lasts': Yankees Tie Franchise Record With 12th Straight Win vs. Red Sox". ESPN. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Appel 2012, pp. 142–143, 212.

- Stout 2002, pp. 116–118.

- Enders 2007, pp. 68–69.

- Appel 2012, pp. 151–152.

- Stout 2002, pp. 122, 126–128.

- Graham 1948, p. 133.

- Trachtenberg 1995, p. 158.