Bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species Bos taurus (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions, including for sacrifices. These animals play a significant role in beef ranching, dairy farming, and a variety of sporting and cultural activities, including bullfighting and bull riding. Their use in herd maintenance is part of their monetary value.

Due to their temperament, handling requires precautions.[1]

Nomenclature

The female counterpart to a bull is a cow, while a male of the species that has been castrated is a steer, ox,[2] or bullock, although in North America, this last term refers to a young bull. Use of these terms varies considerably with area and dialect. Colloquially, people unfamiliar with cattle may refer to both castrated and intact animals as "bulls".

A wild, young, unmarked bull is known as a micky in Australia.[3] Improper or late castration on a bull results in him becoming a coarse steer, also known as a stag in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.[4] In some countries, an incompletely castrated male is known also as a rig or ridgling.

The word "bull" also denotes the males of other bovines, including bison and water buffalo, as well as many other species of large animals, including elephants, rhinos, seals and walruses, hippos, camels, giraffes, elk, moose, whales, and antelopes.

Characteristics

Bulls are much more muscular than cows, with thicker bones, larger feet, a very muscular neck, and a large, bony head with protective ridges over the eyes. These features assist bulls in fighting for domination over a herd, giving the winner superior access to cows for reproduction.[5] The hair is generally shorter on the body, but the neck and head often have a "mane" of curlier, wooly hair. Bulls are usually about the same height as cows or a little taller, but because of the additional muscle and bone mass, they often weigh far more. Most of the time, a bull has a hump on his shoulders.[6]

In horned cattle, the horns of bulls tend to be thicker and somewhat shorter than those of cows,[7] and in many breeds, they curve outwards in a flat arc rather than upwards in a lyre shape. It is not true, as is commonly believed, that bulls have horns and cows do not: the presence of horns depends on the breed, or in horned breeds on whether the horns have been disbudded. (It is true, however, that in many breeds of sheep only the males have horns.) Cattle that naturally do not have horns are referred to as polled, or muleys.[8]

Castrated male cattle are physically similar to females in build and horn shape, although if allowed to reach maturity, they may be considerably taller than either bulls or cows, with heavily muscled shoulders and necks.[9]

Reproductive anatomy

_(20553750880).jpg.webp)

Bulls become fertile around seven months of age. Their fertility is closely related to the size of their testicles, and one simple test of fertility is to measure the circumference of the scrotum; a young bull is likely to be fertile once this reaches 28 centimetres (11 in); that of a fully adult bull may be over 40 centimetres (16 in).[10][11] Bulls have a fibroelastic penis. Given the small amount of erectile tissue, little enlargement occurs after erection. The penis is quite rigid when not erect, and becomes even more rigid during erection. Protrusion is not affected much by erection, but more by relaxation of the retractor penis muscle and straightening of the sigmoid flexure.[12][13][14] Bulls are occasionally affected by a condition known as "corkscrew penis".[15][16] The penis of a mature bull is about 3–4 cm in diameter,[17][18][19][20] and 80–100 cm in length.[21] The bull's glans penis has a rounded and elongated shape.[21]

Misconceptions

A common misconception widely repeated in depictions of bull behavior is that the color red angers bulls, inciting them to charge. In fact, like most mammals, cattle are red–green color blind. In bullfighting, the movement of the matador's cape, and not the color, provokes a reaction in the bull.[22][23]

Management

Beef production

Other than the few bulls needed for breeding, the vast majority of male cattle are castrated and slaughtered for meat before the age of three years, except where they are needed (castrated) as work oxen for haulage. Most of these beef animals are castrated as calves to reduce aggressive behavior and prevent unwanted mating,[24] although some are reared as uncastrated bull beef. A bull is typically ready for slaughter one or two months sooner than a castrated male or a female, and produces proportionately more and leaner muscle.[24]

Frame score is a useful way of describing the skeletal size of bulls and other cattle. Frame scores can be used as an aid to predict mature cattle sizes and aid in the selection of beef bulls. They are calculated from hip height and age. In sales catalogues, this measurement is frequently reported in addition to weight and other performance data such as estimated breed value.[25]

Temperament and handling

Adult bulls may weigh between 500 and 1,000 kg (1,100 and 2,200 lb). Most are capable of aggressive behavior and require careful handling to ensure safety of humans and other animals. Those of dairy breeds may be more prone to aggression, while beef breeds are somewhat less aggressive, though beef breeds such as the Spanish Fighting Bull and related animals are also noted for aggressive tendencies, which are further encouraged by selective breeding.

An estimated 42% of all livestock-related fatalities in Canada are a result of bull attacks, and fewer than one in 20 victims of a bull attack survives.[26] Dairy breed bulls are particularly dangerous and unpredictable; the hazards of bull handling are a significant cause of injury and death for dairy farmers in some parts of the United States.[27][28][29] The need to move a bull in and out of its pen to cover cows exposes the handler to serious jeopardy of life and limb.[30] Being trampled, jammed against a wall, or gored by a bull was one of the most frequent causes of death in the dairy industry before 1940.[1] With regard to such risks, one popular farming magazine has suggested, "Handle the bull with a staff and take no chances. The gentle bull, not the vicious one, most often kills or maims his keeper".[31]

Handling

In many areas, placing rings in bulls' noses to help control them is traditional. The ring is usually made of copper, and is inserted through a small hole cut in the septum of the nose. It is used by attaching a lead rope either directly to it or running through it from a head collar, or for more difficult bulls, a bull pole (or bull staff) may be used. This is a rigid pole about 1 m (3 ft) long with a clip at one end; this attaches to the ring and allows the bull both to be led and to be held away from his handler.

An aggressive bull may be kept confined in a bull pen, a robustly constructed shelter and pen, often with an arrangement to allow the bull to be fed without entering the pen. If an aggressive bull is allowed to graze outside, additional precautions may be needed to help avoid him harming people. One method is a bull mask, which either covers the bull's eyes completely, or restricts his vision to the ground immediately in front of him, so he cannot see his potential victim. Another method is to attach a length of chain to the bull's nose-ring, so that if he ducks his head to charge, he steps on the chain and is brought up short. Alternatively, the bull may be hobbled, or chained by his ring or by a collar to a solid object such as a ring fixed into the ground.

In larger pastures, particularly where a bull is kept with other cattle, the animals may simply be fed from a pickup truck or tractor, the vehicle itself providing some protection for the humans involved. Generally, bulls kept with cows tend to be less aggressive than those kept alone. In herd situations, cows with young calves are often more dangerous to humans. In the off season, multiple bulls may be kept together in a "bachelor herd".

Artificial insemination

Many cattle ranches and stations run bulls with cows, and most dairy or beef farms traditionally had at least one, if not several, bulls for purposes of herd maintenance.[32][33] However, the problems associated with handling a bull (particularly where cows must be removed from his presence to be worked) has prompted many dairy farmers to restrict themselves to artificial insemination (AI) of the cows.[34] Semen is removed from the bulls and stored in canisters of liquid nitrogen, where it is kept until it can be sold, at which time it can be very profitable; in fact, many ranchers keep bulls specifically for this purpose. AI is also used to improve the quality of a herd, or to introduce an outcross of bloodlines. Some ranchers prefer to use AI to allow them to breed to several different bulls in a season or to breed their best stock to a higher-quality bull than they could afford to purchase outright. AI may also be used in conjunction with embryo transfer to allow cattle producers to add new breeding to their herds.

Relationship with humans

Aside from their reproductive duties, bulls are also used in certain sports, including bullfighting and bull-riding. They are also incorporated into festivals and folk events such as the Running of the Bulls and were seen in ancient sports such as bull-leaping. Though less common than castrated males, bulls are used as draught oxen in some areas.[35][36] The once-popular sport of bull-baiting, in which a bull is attacked by specially bred and trained dogs (which came to be known as bulldogs), was banned in England by the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835.

As with other animals, some bulls have been regarded as pets. The singer Charo, for instance, has owned a pet bull named Manolo.[37]

Significance in human culture

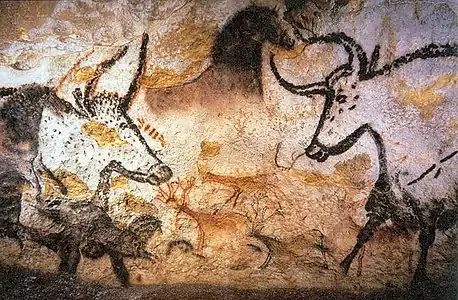

Sacred bulls have held a place of significance in human culture since before the beginning of recorded history. They appear in cave paintings estimated to be up to 17,000 years old. The mythic Bull of the Heavens plays a role in the ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, dating as far back as 2150 BC. The importance of the bull is reflected in its appearance in the zodiac as Taurus, and its numerous appearances in mythology, where it is often associated with fertility. See also Korban. In Hinduism, a bull named Nandi, usually depicted seated, is worshipped as the vehicle of the god Shiva and depicted on many of the images of that deity.

Symbolically, the bull appears commonly in heraldry. Bulls appears as charges and crests on the arms of several British families. Winged bulls appear as supporters in the arms of the Worshipful Company of Butchers.[38] In modern times, the bull is used as a mascot by both amateur and professional sports teams.

Bulls also have a special significance in Spanish culture, where the Running of the Bulls celebration occurs every year in summer. During this festival, a group of human runners called "mozos" try to outrace a group of bulls running behind them, while large crowds watch the entire race.[39]

See also

- Cow-calf operation

- Bull market

References

- O.C. Gregg, Ed., Minnesota Farmer's Institute Annual No. 15, Pioneer Press, St. Paul, Minn. (1902), at p. 125; The James Way, The James Manufacturing Co., Ft. Atkinson, Wisc. (1914), p. 103.

- Delbridge, A, et al., Macquarie Dictionary, The Book Printer, Australia, 1991

- Sheena Coupe (ed.), Frontier Country, Vol. 1 (Weldon Russell Publishing, Willoughby, 1989), ISBN 1-875202-01-3

- "Sure Ways to Lose Money on Your Cattle". Spiritwoodstockyards.ca. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- C. J. C. Phillips, Principles of Cattle Production (2010), p. 50.

- Woods, Katie (July 30, 2015). "How to determine if cattle are bulls, steers, cows or heifers - Farm and Dairy". Farm and Dairy. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- Klaus-Dieter Budras, et al, Bovine Anatomy: An Illustrated Text (2003), p. 36.

- "Muley". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- TIM TRAINOR Montana Standard (April 28, 2010). "Example of large steer". Missoulian.com. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- "A P Carter, P D P Wood and Penelope A Wright (1980), Association between scrotal circumference, live weight and sperm output in cattle, Journal of Reproductive Fertility, 59, pp 447–451". Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- "G Jayawardhana (2006), Testicle Size – A Fertility Indicator in Bulls, Australian Government Agnote K44" (PDF). Northern Territory of Australian. Agnote. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- Sarkar, A. (2003). Sexual Behaviour In Animals. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-746-9.

- Reece, William O. (March 4, 2009). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals – William O. Reece – Google Boeken. ISBN 978-0-8138-1451-3. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- Gillespie, James R.; Flanders, Frank (January 28, 2009). Modern Livestock and Poultry Production – James R. Gillespie, Frank B. Flanders – Google Boeken. ISBN 978-1-4283-1808-3. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- Fubini, Susan L; Ducharme, Norm (January 15, 2004). Farm Animal Surgery. ISBN 1-4160-6465-6.

- Price, Edward O (2008). Principles and Applications of Domestic Animal Behavior: An Introductory Text. ISBN 978-1-78064-055-6.

- Descôteaux, Luc; Colloton, Jill; Gnemmi, Giovanni (September 24, 2009). Practical Atlas of Ruminant and Camelid Reproductive Ultrasonography. ISBN 9780813808079. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- Scott, Phillip; Penny, Colin D.; MacRae, Alastair (July 15, 2011). Cattle Medicine – Philip R. Scott, Colin D. Penny, Alastair Macrae. ISBN 9781840766110. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- McEntee, Mark (August 28, 1990). Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals – Mark McEntee. ISBN 9780323138048. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- Jackson, Peter; Cockcroft, Peter (April 15, 2008). Clinical Examination of Farm Animals – Peter Jackson, Peter Cockcroft. ISBN 9781405147392. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- Heide Schatten; Gheorghe M. Constantinescu (March 21, 2008). Comparative Reproductive Biology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-39025-2.

- "Longhorn_Information – handling". ITLA. Archived from the original on May 11, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- Ashwin (June 17, 2015). "Do Bulls Hate Red Color?". Science ABC. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- Castration of Calves Factsheet, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, June 2007.

- "Frame scoring of beef cattle". New South Wales Government. Department of Primary Industries. September 13, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Handling Livestock Successfully" (PDF). Canadian Farming Administration. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Larry D. Jacobson, Extension Agricultural Engineer, Safe Work Practices on Dairy Farms, University of Minnesota Extension Services (1989)". University of Minnesota - Extension. www.extension.umn.edu. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

During the last 10 years, 12 farmers in Minnesota were mauled and gored to death by dairy bulls

- Cumberland County (Pa.) Sentinel, Shippensburg, Pa., February 12, 2008 A farmer in Southampton County, Michigan, was killed by a 2000-lb Holstein bull in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, in February, 2008.

- Archived 2018-08-26 at the Wayback Machine The Reading [Pennsylvania]Eagle, March 1, 2010 On February 28, 2010, a farmer near Reading, Pennsylvania was trampled and gored to death by a 2000-lb black Angus bull that he had been urged to get rid of by friends after earlier mishaps. Michelle Park, "Bull attacks, kills owner at South Heidelberg Township farm".

- Alvin H. Clement, We Gotta Have More Jails, The Writer's Club Press, New York (1984–87), at pp. 79-80. A humorous description of moving a cow to a neighbor's Jersey bull for breeding purposes, and the use of a 12-foot bull staff to get the loose-running bull under control after he had already spotted the cow

- Helpful Information for Dairymen, The Farmer, Webb Publishing Co., St. Paul, Minnesota, Mar. 12, 1927, p. 6.

- U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Yearbook 1922, Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. (1922), pp. 325-28 (noting a national on-farm bull population of over 600,000 "scrub" bulls in addition to a multiyear supply of "pure bred" bulls)

- O.C. Gregg, Ed., Minnesota Farmer's Institute Annual No. 15, Pioneer Press, St. Paul, Minn. (1902), pp.129-32 (recommending the keeping and testing of sires for dairy herd improvement).

- C. J. C. Phillips, Principles of Cattle Production (2010), p. 121.

- "John C Barret (1991), "The Economic Role of Cattle in Communal Farming Systems in Zimbabwe", to be published in Zimbabwe Veterinary Journal, p 10" (PDF). Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- "Draught Animal Power, an Overview, Agricultural Engineering Branch, Agricultural Support Systems Division, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations". Fiat Panis. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- Capretto, Lisa (June 10, 2014). "The Unusual Pet That Upset Charo's Neighbors (Video)". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- Arthur Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, T.C. and E.C. Jack, London, 1909, 205-207, https://archive.org/details/completeguidetoh00foxduoft.

- "Pamplona Bull Run | RunningoftheBulls.com". Retrieved November 13, 2020.