Burmese python

The Burmese python (Python bivittatus) is one of the largest species of snakes. It is native to a large area of Southeast Asia and is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.[1] Until 2009, it was considered a subspecies of the Indian python, but is now recognized as a distinct species.[3] It is an invasive species in Florida as a result of the pet trade.[4]

| Burmese python | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Pythonidae |

| Genus: | Python |

| Species: | P. bivittatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Python bivittatus (Kuhl, 1820) | |

| |

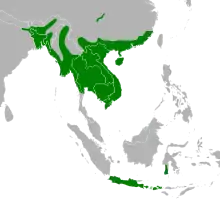

| Native distribution in green | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Python molurus bivittatus Kuhl, 1820 | |

Description

The Burmese python is a dark-colored non-venomous snake with many brown blotches bordered by black down the back. In the wild, Burmese pythons typically grow to 5 m (16 ft),[5][6] while specimens of more than 7 m (23 ft) are unconfirmed.[7] This species is sexually dimorphic in size; females average only slightly longer, but are considerably heavier and bulkier than the males. For example, length-weight comparisons in captive Burmese pythons for individual females have shown: at 3.47 m (11 ft 5 in) length, a specimen weighed 29 kg (64 lb), a specimen of just over 4 m (13 ft) weighed 36 kg (79 lb), a specimen of 4.5 m (15 ft) weighed 40 kg (88 lb), and a specimen of 5 m (16 ft) weighed 75 kg (165 lb). In comparison, length-weight comparisons for males found: a specimen of 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) weighed 12 kg (26 lb), 2.97 m (9 ft 9 in) weighed 14.5 kg (32 lb), a specimen of 3 m (9.8 ft) weighed 7 kg (15 lb), and a specimen of 3.05 m (10.0 ft) weighed 18.5 kg (41 lb).[8][9][10][11][12] In general, individuals over 5 m (16 ft) are rare.[13] The record for maximum length of Burmese pythons is held by a female that lived at Serpent Safari for 27 years. Shortly after death, her actual length was determined to be 5.74 m (18 ft 10 in). Widely published data of specimens reported to have been several feet longer are not verified.[7] At her death, a Burmese named "Baby" was the heaviest snake recorded in the world at the time at 182.8 kg (403 lb),[7] much heavier than any wild snake ever measured.[14] Her length was measured at 5.74 m (18 ft 10 in) circa 1999.[7] The minimum size for adults is 2.35 metres (7 ft 9 in).[15] Dwarf forms occur in Java, Bali, and Sulawesi, with an average length of 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in Bali,[16] and a maximum of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) on Sulawesi.[17] Wild individuals average 3.7 m (12 ft) long,[5][6] but have been known to reach 5.74 m (18 ft 10 in).[7]

Diseases

In both their native and invasive range they suffer from Raillietiella orientalis (a pentastome parasitic disease).[18]

Distribution and habitat

The Burmese python occurs throughout Southern and Southeast Asia, including eastern India, southeastern Nepal, western Bhutan, southeastern Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, northern continental Malaysia, and southern China in Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Hainan, Guangxi, and Yunnan.[19] It also occurs in Hong Kong, and in Indonesia on Java, southern Sulawesi, Bali, and Sumbawa.[20] It has also been reported in Kinmen.[21]

It is an excellent swimmer and needs a permanent source of water. It lives in grasslands, marshes, swamps, rocky foothills, woodlands, river valleys, and jungles with open clearings. It is a good climber and has a prehensile tail. It can stay in water for 30 minutes but mostly stays on land.

As an invasive species

.jpg.webp)

Python invasion has been particularly extensive, notably across South Florida, where a large number of pythons can now be found in the Florida Everglades.[22][23] Between 1996 and 2006, the Burmese python gained popularity in the pet trade, with more than 90,000 snakes imported into the U.S.[24] The current number of Burmese pythons in the Florida Everglades may have reached a minimum viable population and become an invasive species. Hurricane Andrew in 1992 was deemed responsible for the destruction of a python-breeding facility and zoo, and these escaped snakes spread and populated areas into the Everglades.[25] More than 1,330 have been captured in the Everglades.[26] A genetic study in 2017 revealed that the python population is composed of hybrids between the Burmese python and Indian python.[27]

By 2007, the Burmese python was found in northern Florida and in the coastal areas of the Florida Panhandle. The importation of Burmese pythons was banned in the United States in January 2012 by the U.S. Department of the Interior.[28] A 2012 report stated, "in areas where the snakes are well established, foxes, and rabbits have disappeared. Sightings of raccoons are down by 99.3%, opossums by 98.9%, and white-tailed deer by 94.1%."[29] Road surveys between 2003 and 2011 indicated a 87.3% decrease in bobcat populations, and in some areas rabbits have not been detected at all.[30] Experimental efforts to reintroduce rabbit populations to areas where rabbits have been completely eliminated have mostly failed "due to high (77% of mortalities) rates of predation by pythons."[31] Bird and coyote populations may be threatened, as well as the already-rare Florida panther.[29] In addition to this correlational relationship, the pythons have also been experimentally shown to decrease marsh rabbit populations, further suggesting they are responsible for many of the recorded mammal declines. They may also outcompete native predators for food.[32]

For example, Burmese pythons also compete with the native American alligator, and numerous instances of alligators and pythons attacking—and in some cases, preying on—each other have been reported and recorded.

By 2011, researchers identified up to 25 species of birds from nine avian orders in the digestive tract remains of 85 Burmese pythons found in Everglades National Park.[33] Native bird populations are suffering a negative impact from the introduction of the Burmese python in Florida; among these bird species, the wood stork is of specific concern, now listed as federally endangered.[33]

Numerous efforts have been made to eliminate the Burmese python population in the last decade. Understanding the preferred habitat of the species is needed to narrow down the python hunt. Burmese pythons have been found to select broad-leafed and low-flooded habitats. Broad-leafed habitats comprise cypress, overstory, and coniferous forest. Though aquatic marsh environments would be a great source for prey, the pythons seem to prioritize environments allowing for morphological and behavioral camouflage to be protected from predators. Also, the Burmese pythons in Florida have been found to prefer elevated habitats, since this provides the optimal conditions for nesting. In addition to elevated habitats, edge habitats are common places where Burmese pythons are found for thermoregulation, nesting, and hunting purposes.[24]

One of the Burmese python eradication movements with the biggest influence was the 2013 Python Challenge in Florida. This was a month-long contest wherein a total of 68 pythons were removed. The contest offered incentives such as prizes for longest and greatest number of captured pythons. The purpose of the challenge was to raise awareness about the invasive species, increase participation from the public and agency cooperation, and to remove as many pythons as possible from the Florida Everglades.[34]

A study from 2017 introduced a new method for identifying the presence of Burmese pythons in southern Florida; this method involves the screening of mosquito blood. Since the introduction of the Burmese python in Florida, mosquito communities use the pythons as hosts even though they are recently introduced.[35] Invasive Burmese pythons also face certain physiological changes. Unlike their native South Asian counterparts who spend long periods fasting due to seasonal variation in prey availability, pythons in Florida feed year-round due to the constant availability of food. They are also vulnerable to cold stress, with winter freezes resulting in mortality rates of up to 90%. Genomic data suggests natural selection on these populations favors increased thermal tolerance as a result of these high-mortality freezes.[36]

They have carried Raillietiella orientalis (a pentastome parasitic disease) with them from Southeast Asia. Other reptiles in Florida have become infested, and the parasite appears to have become endemic.[18]

In April 2019, researchers captured and killed a large Burmese python in Florida's Big Cypress National Preserve. It was more than 5.2 m (17 ft) long, weighed 140 lb (64 kg), and contained 73 developing eggs.[37] In December 2021, a Burmese python was captured in Florida that weighed 98 kg (215 lb) and had a length of 5.5 m (18 ft); it contained a record 122 developing eggs.[38]

Behavior

Burmese pythons are mainly nocturnal rainforest dwellers.[39] When young, they are equally at home on the ground and in trees, but as they gain girth, they tend to restrict most of their movements to the ground. They are also excellent swimmers, being able to stay submerged for up to half an hour. Burmese pythons spend the majority of their time hidden in the underbrush. In the northern parts of its range, the Burmese python may brumate for some months during the cold season in a hollow tree, a hole in the riverbank, or under rocks. Brumation[40] is biologically distinct from hibernation. While the behavior has similar benefits, allowing organisms to endure the winter without moving, it also involves the preparation of both male and female reproductive organs for the upcoming breeding season. The Florida population also goes through brumation.[41]

They tend to be solitary and are usually found in pairs only when mating. Burmese pythons breed in the early spring, with females laying clutches of 12–36 eggs in March or April. They remain with the eggs until they hatch, wrapping around them and twitching their muscles in such a way as to raise the ambient temperature around the eggs by several degrees. Once the hatchlings use their egg tooth to cut their way out of their eggs, no further maternal care is given. The newly hatched babies often remain inside their eggs until they are ready to complete their first shedding of skin, after which they hunt for their first meal.[42]

Diet

Like all snakes, the Burmese python is carnivorous. Its diet consists primarily of birds and mammals, but also includes amphibians and reptiles. It is a sit-and-wait predator, meaning it spends most of its time staying relatively still, waiting for prey to approach, then striking rapidly.[43] The snake grabs a prey animal with its sharp teeth, then wraps its body around the animal to kill it through constriction.[44] The python then swallows its prey whole. It is often found near human habitation due to the presence of rats, mice, and other vermin as a food source. However, its equal affinity for domesticated birds and mammals means it is often treated as a pest. In captivity, its diet consists primarily of commercially available appropriately sized rats, graduating to larger prey such as rabbits and poultry as it grows. As an invasive species in Florida, Burmese pythons primarily eat a variety of small mammals including foxes, rabbits, and raccoons. Due to their high predation levels, they have been implicated in the decline and even disappearance of many mammal species.[4][32] In their invasive range, pythons also eat birds and occasionally other reptiles. Exceptionally large pythons may even require larger food items such as pigs or goats, and are known to have attacked and eaten alligators and adult deer in Florida.[45][46]

Digestion

The digestive response of Burmese pythons to such large prey has made them a model species for digestive physiology. Its sit-and-wait hunting style is characterized by long fasting periods in between meals, with Burmese pythons typically feeding every month or two, but sometimes fasting for as long as 18 months.[43] As digestive tissues are energetically costly to maintain, they are downregulated during fasting periods to conserve energy when they are not in use.[47] A fasting python has a reduced stomach volume and acidity, reduced intestinal mass, and a 'normal' heart volume. After ingesting prey, the entire digestive system undergoes a massive re-modelling, with rapid hypertrophy of the intestines, production of stomach acid, and a 40% increase in mass of the ventricle of the heart to fuel the digestive process.[48] During digestion, the snake's oxygen consumption rises drastically as well, increasing with meal size by 17 to 40 times its resting rate.[43] This dramatic increase is a result of the energetic cost of restarting many aspects of the digestive system, from rebuilding the stomach and small intestine to producing hydrochloric acid to be secreted in the stomach. Hydrochloric acid production is a significant component of the energetic cost of digestion, as digesting whole prey items requires the animal to be broken down without the use of teeth, either for chewing or tearing into smaller pieces. To compensate, once food has been ingested, Burmese pythons begin producing large amounts of acid to make the stomach acidic enough to turn the food into a semi-liquid that can be passed through to the small intestine and undergo the rest of the digestive process.

The energy cost is highest in the first few days after eating when these regenerative processes are most active, meaning Burmese pythons rely on existing food energy storage to digest a new meal.[43][49] Overall, the entire digestive process from food intake to defecation lasts 8–14 days.[47]

Conservation

The Burmese python is listed on CITES Appendix II.[1] It has been listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 2012, as the wild population is estimated to have declined by at least 30% in the first decade of the 21st century due to habitat loss and over-harvesting.[1]

To maintain Burmese python populations, the IUCN recommends increased conservation legislation and enforcement at the national and international levels to reduce harvesting across the snake's native range. The IUCN also recommends increased research into its population ecology and threats. In Hong Kong, it is a protected species under Wild Animals Protection Ordinance Cap 170. It is also protected in Thailand, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia. However, it is still common only in Hong Kong and Thailand, with rare to very rare statuses in the rest of its range.

In captivity

Burmese pythons are often sold as pets, and are made popular by their attractive coloration and apparently easy-going nature. However, they have a rapid growth rate, and can exceed 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) in length in a year if power fed. However this may cause health issues in the future. By age four, they will have reached their adult size, though they continue growing very slowly throughout their lives, which may exceed 20 years.

Although the species has a reputation for docility, they are very powerful animals – capable of inflicting severe bites and even killing by constriction.[50][51][52][53][54][55] They also consume large amounts of food, and due to their size, require large, often custom-built, secure enclosures. As a result, some are released into the wild, and become invasive species that devastate the environment. For this reason, some jurisdictions (including Florida, due to the python invasion in the Everglades[56]) have placed restrictions on the keeping of Burmese pythons as pets. Violators could be imprisoned for more than seven years or fined $500,000 if convicted.

Burmese pythons are opportunistic feeders;[57] they eat almost any time food is offered, and often act hungry even when they have recently eaten. As a result, they are often overfed, causing obesity-related problems to be common in captive Burmese pythons.

Like the much smaller ball python, Burmese pythons are known to be easygoing or timid creatures, which means that if cared for properly, they can easily adjust to living near humans.[58]

Handling

Although pythons are typically afraid of people due to their great stature, and generally avoid them, special care is still required when handling them. Given their adult strength, multiple handlers (up to one person per meter of snake) are usually recommended.[59] Some jurisdictions require owners to hold special licenses, and as with any wild animal being kept in captivity, treating them with the respect an animal of this size commands is important.[60]

Variations

The Burmese python is frequently captive-bred for color, pattern, and more recently, size. Its amelanistic form is especially popular and is the most widely available morph. This morph is white with patterns in butterscotch yellow and burnt orange. Also, "labyrinth" specimens with maze-like patterns, khaki-colored "green", and "granite" with many small angular spots are available. Breeders have recently begun working with an island lineage of Burmese pythons. Early reports indicate that these dwarf Burmese pythons have slightly different coloring and pattern from their mainland relatives and do not grow much over 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) in length. One of the most sought-after of these variations is the leucistic Burmese. This particular variety is very rare, being entirely bright white with no pattern and blue eyes, and has only in 2008/2009 been reproduced in captivity as the homozygous form (referred to as "super" by reptile keepers) of the co-dominant hypomelanistic trait. The caramel Burmese python has a caramel-colored pattern with "milk-chocolate" eyes.

See also

- Inclusion body disease, a viral disease affecting pythons

References

- Stuart, B.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Thy, N.; Grismer, L.; Chan-Ard, T.; Iskandar, D.; Golynsky, E. & Lau, M.W. (2019) [errata version of 2019 assessment]. "Python bivittatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T193451A151341916. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Python bivittatus at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database

- Jacobs, H.J.; Auliya, M.; Böhme, W. (2009). "On the taxonomy of the Burmese Python, Python molurus bivittatus KUHL, 1820, specifically on the Sulawesi population". Sauria. 31 (3): 5–11.

- Sarill, M. (2016). "Burmese Pythons in the Everglades". Berkeley Rausser College of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- Smith MA (1943). The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma, Including the Whole of the Indo-Chinese Sub-region. Reptilia and Amphibia. Vol. III.—Serpentes. London: Secretary of State for India. (Taylor and Francis, printers). xii + 583 pp. (Python molurus bivittatus, pp. 108–109).

- Campden-Main SM (1970). A Field Guide to the Snakes of South Vietnam. Washington, District of Columbia. pp. 8–9.

- Barker, D.G.; Barten, S.L.; Ehrsam, J.P. & Daddono, L. (2012). "The corrected lengths of two well-known giant pythons and the establishment of a new maximum length record for Burmese Pythons, Python bivittatus" (PDF). Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society. 47 (1): 1–6. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- Van Mierop, L.H. & Barnard, S.M. (1976). "Observations on the reproduction of Python molurus bivittatus (Reptilia, Serpentes, Boidae)". Journal of Herpetology. 10 (4): 333–340. doi:10.2307/1563071. JSTOR 1563071.

- Barker, D.G.; Murphy J.B. & Smith, K.W. (1979). "Social behavior in a captive group of Indian pythons, Python molurus (Serpentes, Boidae) with formation of a linear social hierarchy". Copeia. 1979 (3): 466–471. doi:10.2307/1443224. JSTOR 1443224.

- Marcellini, D.L. & Peters, A. (1982). "Preliminary observations on endogeneous heat production after feeding in Python molurus". Journal of Herpetology. 16 (1): 92–95. doi:10.2307/1563914. JSTOR 1563914.

- Jacobson, E.R.; Homer, B. & Adams, W. (1991). "Endocarditis and congestive heart failure in a Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus)". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 22: 245–248.

- Groot, T.V.; Bruins, E. & Breeuwer, J.A. (2003). "Molecular genetic evidence for parthenogenesis in the Burmese python, Python molurus bivittatus". Heredity. 90 (2): 130–135. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800210. PMID 12634818.

- Saint Girons, H. (1972). "Les serpents du Cambodge". Mémoires du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. Série A: 40–41.

- Rivas, J.A. (2000). The life history of the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus), with emphasis on its reproductive Biology (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). University of Tennessee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

- Murphy, J.C. & Henderson, R.W. (1997). Tales of Giant Snakes: A Historical Natural History of Anacondas and Pythons. Krieger Pub. Co. pp. 2, 19, 37, 42, 55–56. ISBN 0-89464-995-7.

- McKay, J.L. (2006). A Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Bali. Krieger Publishing Company. pp. 13, 14, 18, 86. ISBN 1-57524-190-0.

- De Lang, R. & Vogel, G. (2005). The Snakes of Sulawesi: A Field Guide to the Land Snakes of Sulawesi with Identification Keys. Frankfurt Contributions to Natural History (Band 25 ed.). Chimaira. pp. 23–27, 198–201. ISBN 3-930612-85-2.

- Waymer, J. (2019). "Bloodsucking worms in pythons are killing Florida snakes, study says". Florida Today. Retrieved 2021-12-16.

- Barker, D.G.; Barker, T.M. (2010). "The Distribution of the Burmese Python, Python bivittatus, in China" (PDF). Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society. 45 (5): 86–88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- Barker, D.G.; Barker, T.M. (2008). "The distribution of the Burmese Python, Python molurus bivittatus" (PDF). Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society. 43 (3): 33–38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-20. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- Breuer, H.; Murphy, W.C. (2009–2010). "Python molurus bivittatus". Snakes of Taiwan. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- "Top 10 Invasive Species". Time. 2010. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Species Profile - Burmese Python (Python molurus bivittatus). National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library.

- Walters, T. M., Mazzotti, F. J., & Fitz, H. C. (2016). "Habitat selection by the invasive species Burmese python in Southern Florida". Journal of Herpetology, 50 (#1), 50–56.

- "Democrats Hold Hearing on Administration's Plan to Constrict Snakes in the Everglades - House Committee on Natural Resources". Naturalresources.house.gov. 2010. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "(US National Park Service website - December 31, 2009)". nps.gov. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Hunter, M.E.; Johnson, N.A.; Smith, B.J.; Davis, M.C.; Butterfield, John S.S.; Snow, R.W.; Hart, K.M. (2017). "Cytonuclear discordance in the Florida Everglades invasive Burmese python (Python bivittatus) population reveals possible hybridization with the Indian python (P. molurus)". Ecology and Evolution. 8 (17): 9034–9047. doi:10.1002/ece3.4423. PMC 6157680. PMID 30271564.

- "Salazar Announces Ban on Importation and Interstate Transportation of Four Giant Snakes that Threaten Everglades". doi.gov (Press release). January 17, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- Adams, G. (2012). "Pythons are squeezing the life out of the Everglades, scientists warn". The Independent. London.

- Dorcas, M.E.; Willson, J.D.; Reed, R.N.; Snow, R.W.; Rochford, M.R.; Miller, M.A.; Meshaka, W.E.; Andreadis, P.T.; Mazzotti, F.J.; Romagosa, C.M.; Hart, K.M. (2012). "Severe mammal declines coincide with proliferation of invasive Burmese pythons in Everglades National Park". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (7): 2418–2422. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115226109. PMC 3289325. PMID 22308381.

- Willson, J. (2017). "Indirect effects of invasive Burmese pythons on ecosystems in southern Florida". Journal of Applied Ecology. 54 (4): 1251–1258. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12844.

- McCleery, R.A.; Sovie, A.; Reed, R.N.; Cunningham, M.W.; Hunter M.E.; Hart, K.M. (2015). "Marsh rabbit mortalities tie pythons to the precipitous decline of mammals in the Everglades". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1805): 20150120. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0120. PMC 4389622. PMID 25788598.

- Dove, C. J., Snow, R. W., Rochford, M. R., & Mazzotti, F. J. (2011). BIRDS CONSUMED BY THE INVASIVE BURMESE PYTHON (PYTHON MOLURUS BIVITTATUS) IN EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK, FLORIDA, USA. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 123(#1), 126–131.

- Mazzotti, F. J., Rochford, M., Vinci, J., Jeffery, B. M., Eckles, J. K., Dove, C., & Sommers, K. P. (2016). "Implications of the 2013 Python Challenge® for Ecology and Management of Python molorus bivittatus (Burmese python) in Florida". Southeastern Naturalist, 15 (sp8), 63–74.

- Reeves LE, Krysko KL, Avery ML, Gillett-Kaufman JL, Kawahara AY, Connelly CR, Kaufman PE (2018-01-17). Paul R (ed.). "Interactions between the invasive Burmese python, Python bivittatus Kuhl, and the local mosquito community in Florida, USA". PLOS ONE. 13 (1): e0190633. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1390633R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190633. PMC 5771569. PMID 29342169.

- Card DC, Perry BW, Adams RH, Schield DR, Young AS, Andrew AL, et al. (2018). "Novel ecological and climatic conditions drive rapid adaptation in invasive Florida Burmese pythons". Molecular Ecology. 27 (23): 4744–4757. doi:10.1111/mec.14885. PMID 30269397.

- Mettler, K. "A 17-foot, 140-pound python was captured in a Florida park. Officials say it's a record". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Williams, A. B. "Caught! Record-breaking 18-foot Burmese python pulled from Collier County wilderness". The News-Press. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- Evans S (2003). "Python molurus, Burmese Python". The deep Scaly Project. Digital Morphology. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- "Glossary of reptile and amphibian terminology". Kingsnake.com. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Shaul, Travis R.; Shaul, Kylienne A.; Weaver, Ella M. 1.4 INVASIVE SPECIES BURMESE PYTHON (PYTHON BIVITTATUS) AND ITS EFFECT IN FLORIDA. The Ohio State University.

{{cite book}}: Missing|author1=(help) - Ghosh A (11 July 2012). "Burmese Python". AnimalSpot.net. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Secor SM, Diamond J (June 1995). "Adaptive responses to feeding in Burmese pythons: pay before pumping". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 198 (Pt 6): 1313–25. doi:10.1242/jeb.198.6.1313. PMID 7782719.

- Szalay J (February 2016). "Python Facts". livescience.com. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- "Photo in the News: Python Bursts After Eating Gator (Update)". National Geographic News. 5 September 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Large Python Captured, Killed After Devouring Adult Deer | KSEE 24 News - Central Valley's News Station: Fresno-Visalia - News, Sports, Weather | Local News". Ksee24.com. 2011-10-31. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Starck JM, Beese K (January 2001). "Structural flexibility of the intestine of Burmese python in response to feeding". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (Pt 2): 325–35. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.2.325. PMID 11136618.

- Secor, Stephen M. (2008-12-15). "Digestive physiology of the Burmese python: broad regulation of integrated performance". Journal of Experimental Biology. Jeb.biologists.org. 211 (24): 3767–3774. doi:10.1242/jeb.023754. PMID 19043049. S2CID 5545174. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Secor SM (May 2003). "Gastric function and its contribution to the postprandial metabolic response of the Burmese python Python molurus". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 206 (Pt 10): 1621–30. doi:10.1242/jeb.00300. PMID 12682094.

- "Python Kills Careless Student Zookeeper in Caracas". The Telegraph. London. AP. 2008-08-26. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- Chiszar D, Smith HM, Petkus A, Doughery J (1993). "A Fatal Attack on a Teenage Boy by a Captive Burmese Python (Python molurus bivittatus) in Colorado" (pdf). The Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society. Chicago Herpetological Society. 28 (#12): 261. ISSN 0009-3564. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-18.

- Kaplan M (1994). "The Keeping of Large Pythons: Realities and Responsibilities". www.anapsid.org. Herp Care Collection. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- "Python Caused Death in Ontario Home in 1992 Case". Toronto News. CBC News. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Commission. Canadian Press. 2013-04-13. ISSN 0708-9392. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- Davison J (2013-08-07). "Python-linked Deaths Raise Questions over Exotic Animal Laws". News. CBC News. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. ISSN 0708-9392. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- "Dr. D. H. Evans, Coroner of Ontario, "Inquest into the Death of Mark Nevilles: Verdict of Coroner's Jury" (Brampton, Ontario: June 1992)". documentcloud.org. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Burrage G (30 June 2010). "New law makes Burmese python illegal in Florida". Abcactionnews.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-01. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Orzechowski, Sophia C. M.; Romagosa, Christina M.; Frederick, Peter C. (2019-07-01). "Invasive Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) are novel nest predators in wading bird colonies of the Florida Everglades". Biological Invasions. 21 (7): 2333–2344. doi:10.1007/s10530-019-01979-x. ISSN 1573-1464. S2CID 102350541.

- "Python bivittatus (Kuhl, 1820)". www.gbif.org. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Playing with the Big Boys: Handling Large Constrictors". www.anapsid.org. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Captive Animals - Most states have no laws governing captive wild animals". Animal Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

Further reading

- Christy (2008). The Lizard King: The True Crimes and Passions of the World's Greatest Reptile Smugglers. New York: TWELVE. ISBN 978-0-446-58095-3.

- Mattison C (1999). Snake. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7894-4660-2.

- Willson JD, Dorcas ME, Snow RW (2010-11-21). "Identifying plausible scenarios for the establishment of invasive Burmese pythons (Python molurus) in Southern Florida". Biological Invasions. 13 (7): 1493–1504. doi:10.1007/s10530-010-9908-3. ISSN 1387-3547. S2CID 207096799.

External links

- Burmese python (Python molurus) - EDDMapS State Distribution - EDDMapS

- Species profile - Burmese Python (Python molurus), National Invasive Species Information Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library