Sequoia sempervirens

Sequoia sempervirens (/səˈkwɔɪ.ə ˌsɛmpərˈvaɪrənz/)[3] is the sole living species of the genus Sequoia in the cypress family Cupressaceae (formerly treated in Taxodiaceae). Common names include coast redwood, coastal redwood,[4] and California redwood.[5] It is an evergreen, long-lived, monoecious tree living 1,200–2,200 years or more.[6] This species includes the tallest living trees on Earth, reaching up to 115.9 m (380.1 ft) in height (without the roots) and up to 8.9 m (29 ft) in diameter at breast height. These trees are also among the oldest living things on Earth. Before commercial logging and clearing began by the 1850s, this massive tree occurred naturally in an estimated 810,000 ha (2,000,000 acres)[7][8][9] along much of coastal California (excluding southern California where rainfall is not sufficient) and the southwestern corner of coastal Oregon within the United States.

| Sequoia sempervirens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sequoia sempervirens along US 199 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnosperms |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Genus: | Sequoia |

| Species: | S. sempervirens |

| Binomial name | |

| Sequoia sempervirens (D.Don) Endl. | |

| |

| Natural range of California subfamily Sequoioideae

green - Sequoia sempervirens

red - Sequoiadendron giganteum | |

The name sequoia sometimes refers to the subfamily Sequoioideae, which includes S. sempervirens along with Sequoiadendron (giant sequoia) and Metasequoia (dawn redwood). Here, the term redwood on its own refers to the species covered in this article but not to the other two species.

Description

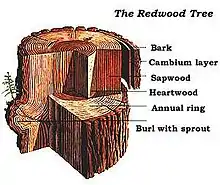

The coast redwood is known to have reached 115.5 m or 380.1 ft tall, with a trunk diameter of 9 m (30 ft).[10] It has a conical crown, with horizontal to slightly drooping branches. The trunk is remarkably straight. The bark can be very thick, up to 30 cm (1 ft), and quite soft and fibrous, with a bright red-brown color when freshly exposed (hence the name redwood), weathering darker. The root system is composed of shallow, wide-spreading lateral roots.

The leaves are variable, being 15–25 mm (5⁄8–1 in) long and flat on young trees and shaded lower branches in older trees. The leaves are scalelike, 5–10 mm (1⁄4–3⁄8 in) long on shoots in full sun in the upper crown of older trees, with a full range of transition between the two extremes. They are dark green above and have two blue-white stomatal bands below. Leaf arrangement is spiral, but the larger shade leaves are twisted at the base to lie in a flat plane for maximum light capture.

The species is monoecious, with pollen and seed cones on the same plant. The seed cones are ovoid, 15–32 mm (9⁄16–1+1⁄4 in) long, with 15–25 spirally arranged scales; pollination is in late winter with maturation about 8–9 months after. Each cone scale bears three to seven seeds, each seed 3–4 mm (1⁄8–3⁄16 in) long and 0.5 mm (1⁄32 in) broad, with two wings 1 mm (1⁄16 in) wide. The seeds are released when the cone scales dry out and open at maturity. The pollen cones are ovular and 4–6 mm (3⁄16–1⁄4 in) long.

Its genetic makeup is unusual among conifers, being a hexaploid (6n) and possibly allopolyploid (AAAABB).[11] Both the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes of the redwood are paternally inherited.[12]

Taxonomy

Scottish botanist David Don described the redwood as the evergreen taxodium (Taxodium sempervirens) in his colleague Aylmer Bourke Lambert's 1824 work A description of the genus Pinus.[13] Austrian botanist Stephan Endlicher erected the genus Sequoia in his 1847 work Synopsis coniferarum, giving the redwood its current binomial name of Sequoia sempervirens.[14] Endlicher probably derived the name Sequoia from the Cherokee name of George Gist, usually spelled Sequoyah, who developed the still-used Cherokee syllabary.[15] The redwood is one of three living species, each in its own genus, in the subfamily Sequoioideae. Molecular studies have shown that the three are each other's closest relatives, generally with the redwood and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) as each other's closest relatives. However, Yang and colleagues in 2010 queried the polyploid state of the redwood and speculate that it may have arisen as an ancient hybrid between ancestors of the giant sequoia and dawn redwood (Metasequoia). Using two different single copy nuclear genes, LFY and NLY, to generate phylogenetic trees, they found that Sequoia was clustered with Metasequoia in the tree generated using the LFY gene, but with Sequoiadendron in the tree generated with the NLY gene. Further analysis strongly supported the hypothesis that Sequoia was the result of a hybridization event involving Metasequoia and Sequoiadendron. Thus, Yang and colleagues hypothesize that the inconsistent relationships among Metasequoia, Sequoia, and Sequoiadendron could be a sign of reticulate evolution (in which two species hybridize and give rise to a third) among the three genera. However, the long evolutionary history of the three genera (the earliest fossil remains being from the Jurassic) make resolving the specifics of when and how Sequoia originated once and for all a difficult matter—especially since it in part depends on an incomplete fossil record.[16]

Distribution and habitat

Coast redwoods occupy a narrow strip of land approximately 750 km (470 mi) in length and 8–75 km (5–47 mi) in width along the Pacific coast of North America; the most southerly grove is in Monterey County, California, and the most northerly groves are in extreme southwestern Oregon. The prevailing elevation range is 30–750 m (100–2,460 ft) above sea level, occasionally down to 0 and up to about 900 m (3,000 ft).[17] They usually grow in the mountains where precipitation from the incoming moisture off the ocean is greater. The tallest and oldest trees are found in deep valleys and gullies, where year-round streams can flow, and fog drip is regular. The terrain also made it harder for loggers to get to the trees and to get them out after felling. The trees above the fog layer, above about 700 m (2,300 ft), are shorter and smaller due to the drier, windier, and colder conditions. In addition, Douglas-fir, pine, and tanoak often crowd out redwoods at these elevations. Few redwoods grow close to the ocean, due to intense salt spray, sand, and wind. Coalescence of coastal fog accounts for a considerable part of the trees' water needs.[18]

The northern boundary of its range is marked by two groves on mountain slopes along the north side of the Chetco River,[19] which is on the western fringe of the Klamath Mountains, near the California-Oregon border.[20][21] The northernmost grove is located within Alfred A. Loeb State Park and Siskiyou National Forest at the approximate coordinates 42°07'36"N 124°12'17"W. The southern boundary of its range is the Los Padres National Forest's Silver Peak Wilderness in the Santa Lucia Mountains of the Big Sur area of Monterey County, California. The southernmost grove is in the Southern Redwood Botanical Area, just north of the national forest's Salmon Creek trailhead and near the San Luis Obispo County line.[22][23]

The largest and tallest populations are in California's Redwood National and State Parks (Del Norte and Humboldt counties) and Humboldt Redwoods State Park, with the overall majority located in the large Humboldt County.

The prehistoric fossil range of the genus is considerably greater, with a subcosmopolitan distribution including Europe and Asia until about 5 million years ago. During the last ice age, perhaps as recently as 10,000 years ago, redwood trees grew as far south as the Los Angeles area (coast redwood bark found in subway excavations and at La Brea Tar Pits).

Ecology

This native area provides a unique environment with heavy seasonal rains up to 2,500 mm (100 in) annually. Cool coastal air and fog drip keep this forest consistently damp year round. Several factors, including the heavy rainfall, create a soil with fewer nutrients than the trees need, causing them to depend heavily on the entire biotic community of the forest, and making efficient recycling of dead trees especially important. This forest community includes coast Douglas-fir, Pacific madrone, tanoak, western hemlock, and other trees, along with a wide variety of ferns, mosses, mushrooms, and redwood sorrel. Redwood forests provide habitat for a variety of amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles. Old-growth redwood stands provide habitat for the federally threatened spotted owl and the California-endangered marbled murrelet.

Coast redwoods are resistant to insect attack, fungal infection, and rot. These properties are conferred by concentrations of terpenoids and tannic acid in redwood leaves, roots, bark, and wood.[24] Despite these chemical defenses, redwoods are still subject to insect infestations; none, however, are capable of killing a healthy tree.[24] Redwoods also face herbivory from mammals: black bears are reported to consume the inner bark of small redwoods, and black-tailed deer are known to eat redwood sprouts.[24]

The oldest known coast redwood is about 2,200 years old;[25] many others in the wild exceed 600 years. The numerous claims of older redwoods are incorrect.[25] Because of their seemingly timeless lifespans, coast redwoods were deemed the "everlasting redwood" at the turn of the century; in Latin, sempervirens means "ever green" or "everlasting". Redwoods must endure various environmental disturbances to attain such great ages. In response to forest fires, the trees have developed various adaptations. The thick, fibrous bark of coast redwoods is extremely fire-resistant; it grows to at least a foot thick and protects mature trees from fire damage.[26][27] In addition, the redwoods contain little flammable pitch or resin.[27] If damaged by fire, a redwood readily sprouts new branches or even an entirely new crown,[26][24] and if the parent tree is killed, new buds sprout from its base.[24] Fires, moreover, appear to actually benefit redwoods by causing substantial mortality in competing species while having only minor effects on redwood. Burned areas are favorable to the successful germination of redwood seeds.[26] A study published in 2010, the first to compare post-wildfire survival and regeneration of redwood and associated species, concluded fires of all severity increase the relative abundance of redwood and higher-severity fires provide the greatest benefit.[28]

Redwoods often grow in flood-prone areas. Sediment deposits can form impermeable barriers that suffocate tree roots, and unstable soil in flooded areas often causes trees to lean to one side, increasing the risk of the wind toppling them. Immediately after a flood, redwoods grow their existing roots upwards into recently deposited sediment layers.[29] A second root system then develops from adventitious buds on the newly buried trunk and the old root system dies.[29] To counter lean, redwoods increase wood production on the vulnerable side, creating a supporting buttress.[29] These adaptations create forests of almost exclusively redwood trees in flood-prone regions.[24][29]

The height of S. sempervirens is closely tied to fog availability; taller trees become less frequent as fog becomes less frequent.[30] As S. sempervirens' height increases, transporting water via water potential to the leaves becomes increasingly difficult due to gravity.[31][32][33] Despite the high rainfall that the region receives (up to 100 cm), the leaves in the upper canopy are perpetually stressed for water.[34][35] This water stress is exacerbated by long droughts in the summer.[36] Water stress is believed to cause the morphological changes in the leaves, stimulating reduced leaf length and increased leaf succulence.[32][37] To supplement their water needs, redwoods utilize frequent summer fog events. Fog water is absorbed through multiple pathways. Leaves directly take in fog from the surrounding air through the epidermal tissue, bypassing the xylem.[38][39] Coast redwoods also absorb water directly through their bark.[40] The uptake of water through leaves and bark repairs and reduces the severity of xylem embolisms,[41][40] which occur when cavitations form in the xylem preventing the transport of water and nutrients.[40] Fog may also collect on redwood leaves, drip to the forest floor, and be absorbed by the tree's roots. This fog drip may form 30% of the total water used by a tree in a year.[36]

Reproduction

Coast redwood reproduces both sexually by seed and asexually by sprouting of buds, layering, or lignotubers. Seed production begins at 10–15 years of age. Cones develop in the winter and mature by fall. In the early stages, the cones look like flowers, and are commonly called "flowers" by professional foresters, although this is not strictly correct. Coast redwoods produce many cones, with redwoods in new forests producing thousands per year.[26] The cones themselves hold 90–150 seeds, but viability of seed is low, typically well below 15% with one estimate of average rates being 3 to 10 percent.[42][26] The low viability may discourage seed predators, which do not want to waste time sorting chaff (empty seeds) from edible seeds. Successful germination often requires a fire or flood, reducing competition for seedlings. The winged seeds are small and light, weighing 3.3–5.0 mg (200–300 seeds/g; 5,600–8,500/ounce). The wings are not effective for wide dispersal, and seeds are dispersed by wind an average of only 60–120 m (200–390 ft) from the parent tree. Seedlings are susceptible to fungal infection and predation by banana slugs, brush rabbits, and nematodes.[24] Most seedlings do not survive their first three years.[26] However, those that become established grow rapidly, with young trees known to reach 20 m (66 ft) tall in 20 years.

Coast redwoods can also reproduce asexually by layering or sprouting from the root crown, stump, or even fallen branches; if a tree falls over, it generates a row of new trees along the trunk, so many trees naturally grow in a straight line. Sprouts originate from dormant or adventitious buds at or under the surface of the bark. The dormant sprouts are stimulated when the main adult stem gets damaged or starts to die. Many sprouts spontaneously erupt and develop around the circumference of the tree trunk. Within a short period after sprouting, each sprout develops its own root system, with the dominant sprouts forming a ring of trees around the parent root crown or stump. This ring of trees is called a "fairy ring". Sprouts can achieve heights of 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) in a single growing season.

Redwoods may also reproduce using burls. A burl is a woody lignotuber that commonly appears on a redwood tree below the soil line, though usually within 3 m (10 ft) in depth from the soil surface. Coast redwoods develop burls as seedlings from the axils of their cotyledon, a trait that is extremely rare in conifers.[26] When provoked by damage, dormant buds in the burls sprout new shoots and roots. Burls are also capable of sprouting into new trees when detached from the parent tree, though exactly how this happens is yet to be studied. Shoot clones commonly sprout from burls and are often turned into decorative hedges when found in suburbia.

Cultivation and uses

Coast redwood is one of the most valuable timber species in the lumbering industry. In California, 3,640 km2 (899,000 acres) of redwood forest are logged, virtually all of it second growth.[1] Though many entities have existed in the cutting and management of redwoods, perhaps none has had a more storied role than the Pacific Lumber Company (1863–2008) of Humboldt County, California, where it owned and managed over 810 km2 (200,000 acres) of forests, primarily redwood. Coast redwood lumber is highly valued for its beauty, light weight, and resistance to decay. Its lack of resin makes it absorb water[43] and resist fire.

P.H. Shaughnessy, Chief Engineer of the San Francisco Fire Department wrote:

In the recent great fire of San Francisco, that began April 18th, 1906, we succeeded in finally stopping it in nearly all directions where the unburned buildings were almost entirely of frame construction, and if the exterior finish of these buildings had not been of redwood lumber, I am satisfied that the area of the burned district would have been greatly extended.

Because of its impressive resistance to decay, redwood was extensively used for railroad ties and trestles throughout California. Many of the old ties have been recycled for use in gardens as borders, steps, house beams, etc. Redwood burls are used in the production of table tops, veneers, and turned goods.

The Yurok people, who occupied the region before European settlement, regularly burned off ground cover in redwood forests to bolster tanoak populations from which they harvested acorns, to maintain forest openings, and to boost populations of useful plant species such as those for medicine or basketmaking.[24]

Extensive logging of redwoods began in the early nineteenth century. The trees were felled by ax and saw onto beds of tree limbs and shrubs to cushion their fall.[24] Stripped of their bark, the logs were transported to mills or waterways by oxen or horse.[24] Loggers then burned the accumulated tree limbs, shrubs, and bark. The repeated fires favored secondary forests of primarily redwoods as redwood seedlings sprout readily in burned areas.[24][44] The introduction of steam engines let crews drag logs through long skid trails to nearby railroads,[24] furthering the reach of loggers beyond the land nearby rivers previously used to transport trees.[44] This method of harvesting, however, disturbed large amounts of soil, producing secondary-growth forests of species other than redwood such as Douglas-fir, grand fir, and western hemlock.[24] After World War II, trucks and tractors gradually replaced steam engines, giving rise to two harvesting approaches: clearcutting and selection harvesting. Clearcutting involved felling all the trees in a particular area. It was encouraged by tax laws that exempted all standing timber from taxation if 70% of trees in the area were harvested.[24] Selection logging, by contrast, called for the removal 25% to 50% of mature trees in the hopes that the remaining trees would allow for future growth and reseeding.[44] This method, however, encouraged growth of other tree species, converting redwood forests into mixed forests of redwood, grand fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock.[44][24] Moreover, the trees left standing were often felled by windthrow; that is, they were often blown over by the wind.

The coast redwood is naturalized in New Zealand, notably at Whakarewarewa Forest, Rotorua.[45] Redwood has been grown in New Zealand plantations for more than 100 years, and those planted in New Zealand have higher growth rates than those in California, mainly because of even rainfall distribution through the year.[46] Other areas of successful cultivation outside of the native range include Great Britain, Italy, Portugal,[47] Haida Gwaii, middle elevations of Hawaii, Hogsback in South Africa, the Knysna Afromontane forests in the Western Cape, Grootvadersbosch Forest Reserve near Swellendam, South Africa and the Tokai Arboretum on the slopes of Table Mountain above Cape Town, a small area in central Mexico (Jilotepec), and the southeastern United States from eastern Texas to Maryland. It also does well in the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia), far north of its northernmost native range in southwestern Oregon. Coast redwood trees were used in a display at Rockefeller Center and then given to Longhouse Reserve in East Hampton, Long Island, New York, and these have now been living there for over twenty years and have survived at 2 °F (−17 °C).[48]

This fast-growing tree can be grown as an ornamental specimen in those large parks and gardens that can accommodate its massive size. It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[49][50]

Statistics

Fairly solid evidence indicates that coast redwoods were the world's largest trees before logging, with numerous historical specimens reportedly over 122 m (400 ft).[51]: 16, 42 The theoretical maximum potential height of coast redwoods is thought to be limited to between 122 and 130 m (400 and 427 ft), as evapotranspiration is insufficient to transport water to leaves beyond this range.[31] Further studies have indicated that this maximum requires fog, which is prevalent in these trees' natural environment.[52]

A tree reportedly 114.3 m (375 ft) in length was felled in Sonoma County by the Murphy Brothers saw mill in the 1870s,[53] another claimed to be 115.8 m (380 ft) and 7.9 m (26 ft) in diameter was cut down near Eureka in 1914,[54][55] and the Lindsey Creek tree was documented to have a height of 120 m (390 ft) when it was uprooted and felled by a storm in 1905. A tree reportedly 129.2 m (424 ft) tall was felled in November 1886 by the Elk River Mill and Lumber Co. in Humboldt County, yielding 79,736 marketable board feet from 21 cuts.[56][57][58] In 1893, a Redwood cut at Eel River, near Scotia, reportedly measured 130.1 m (427 ft) in length, and 23.5 m (77 ft) in girth.[59][60][61] However, limited evidence corroborates these historical measurements.

Today, trees over 60 m (200 ft) are common, and many are over 90 m (300 ft). The current tallest tree is the Hyperion tree, measuring 115.61 m (379.3 ft).[25] The tree was discovered in Redwood National Park during mid-2006 by Chris Atkins and Michael Taylor, and is thought to be the world's tallest living organism. The previous record holder was the Stratosphere Giant in Humboldt Redwoods State Park at 112.84 m (370.2 ft) (as measured in 2004). Until it fell in March 1991, the "Dyerville Giant" was the record holder. It, too, stood in Humboldt Redwoods State Park and was 113.4 m (372 ft) high and estimated to be 1,600 years old. This fallen giant has been preserved in the park.

As of 2016, no living specimen of other tree species exceeds 100 m (330 ft). The largest known living coast redwood is Grogan's Fault, discovered in 2014 by Chris Atkins and Mario Vaden in Redwood National Park,[25] with a main trunk volume of at least 1,084.5 cubic meters (38,299 cu ft)[25] Other high-volume coast redwoods include Iluvatar, with a main trunk volume of 1,033 m3 (36,470 cu ft),[51]: 160 and the Lost Monarch, with a main trunk volume of 988.7 m3 (34,914 cu ft).[62]

Albino redwoods are mutants that cannot manufacture chlorophyll. About 230 examples (including growths and sprouts) are known to exist,[63] reaching heights of up to 20 m (66 ft).[64] These trees survive like parasites, obtaining food from green parent trees. While similar mutations occur sporadically in other conifers, no cases are known of such individuals surviving to maturity in any other conifer species. Recent research news reports that albino redwoods can store higher concentrations of toxic metals, going so far as comparing them to organs or "waste dumps".[65][66]

List of tallest trees

Heights of the tallest coast redwoods are measured yearly by experts.[25] Even with recent discoveries of tall coast redwoods above 100 m (330 ft), it is likely that no taller trees will be discovered.[25]

| Rank | Name | Height | Diameter | Location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meters | Feet | Meters | Feet | |||

| 1 | Hyperion | 115.85 | 380.1 | 4.84 | 15.9 | Redwood National Park |

| 2 | Helios | 114.58 | 375.9 | 4.96 | 16.3 | Redwood National Park |

| 3 | Icarus | 113.14 | 371.2 | 3.78 | 12.4 | Redwood National Park |

| 4 | Stratosphere Giant | 113.05 | 370.9 | 5.18 | 17.0 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| 5 | National Geographic | 112.71 | 369.8 | 4.39 | 14.4 | Redwood National Park |

| 6 | Orion | 112.63 | 369.5 | 4.33 | 14.2 | Redwood National Park |

| 7 | Federation Giant | 112.62 | 369.5 | 4.54 | 14.9 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| 8 | Paradox | 112.51 | 369.1 | 3.90 | 12.8 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| 9 | Mendocino | 112.32 | 368.5 | 4.19 | 13.7 | Montgomery Woods State Natural Reserve |

| 10 | Millennium | 111.92 | 367.2 | 2.71 | 8.9 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

Diameter is measured at 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) above average ground level (at breast height). Details of the precise locations for most tallest trees were not announced to the general public for fear of causing damage to the trees and the surrounding habitat.[25] The tallest coast redwood easily accessible to the public is the National Geographic Tree, immediately trailside in the Tall Trees Grove of Redwood National Park.[67]

List of largest trees

The following list shows the largest S. sempervirens by volume known as of 2001.[51]: 186–7

| Rank | Name | Height | Diameter | Trunk volume | Location | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meters | Feet | Meters | Feet | Cubic meters | Cubic feet | |||

| 1 | Del Norte Titan | 93.6 | 307 | 7.23 | 23.7 | 1,045 | 36,900 | Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park |

| 2 | Iluvatar | 91.4 | 300 | 6.14 | 20.1 | 1,033 | 36,500 | Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park |

| 3 | Lost Monarch | 97.8 | 321 | 7.68 | 25.2 | 989 | 34,900 | Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park |

| 4 | Howland Hill Giant | 100.3 | 329 | 6.02 | 19.8 | 951 | 33,600 | Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park |

| 5 | Sir Isaac Newton | 94.8 | 311 | 7.01 | 23.0 | 940 | 33,000 | Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park |

Calculating the volume of a standing tree is the practical equivalent of calculating the volume of an irregular cone,[68] and is subject to error for various reasons. This is partly due to technical difficulties in measurement, and variations in the shape of trees and their trunks. Measurements of trunk circumference are taken at only a few predetermined heights up the trunk, and assume that the trunk is circular in cross-section, and that taper between measurement points is even. Also, only the volume of the trunk (including the restored volume of basal fire scars) is taken into account, and not the volume of wood in the branches or roots.[68] The volume measurements also do not take cavities into account. Most coast redwoods with volumes greater than 850 m3 (30,000 cu ft) represent ancient fusions of two or more separate trees, which makes determining whether a coast redwood has a single stem or multiple stems difficult.[69] Starting in 2014, more record-breaking coast redwood trees were discovered. The largest disclosed was a massive redwood called Grogan's Fault/Spartan,[70] which has been measured to have a volume of 38,300 cubic feet.

Details of the precise locations for most tallest trees were not announced to the general public for fear of causing damage to the trees and the surrounding habitat.[25] The largest coast redwood easily accessible to the public is Iluvatar, which stands prominently about 5 meters (16 ft) to the southeast of the Foothill Trail of Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park.

Other notable examples

- The Blossom Rock Navigation Trees were two especially tall sequoias located in the Berkeley Hills used as a navigational aid by sailors to avoid the treacherous Blossom Rock near Yerba Buena Island.[71]

- The Crannell Creek Giant was documented to have a trunk volume of at least 1,744 m3 (61,573 cu ft) – about 32% larger than Grogan's Fault and 17% larger than General Sherman, the current largest tree. It was felled around 1945.[25][72]

- The Lindsey Creek tree was documented to have a height of 120 m (390 ft) and a trunk volume of at least 2,500 cubic meters (90,000 cu ft) when it was uprooted and felled by a storm in 1905. If these measurements are to be believed, the Lindsey Creek tree was about 3 m (10 ft) taller than Hyperion, the current tallest tree, 213% larger than Grogan's Fault, and 171% larger than General Sherman.[25][73]

- Old Survivor, also known as the Grandfather, is the last remaining old-growth coastal redwood of the redwood forest that populated the Oakland Hills. The tree was seeded sometime between 1549 and 1554.[74]

- One of the largest redwood stumps ever found, measuring 9.4 m (31 ft) in diameter, is in Oakland, California, the Berkeley Hills, in the Roberts Regional Recreation Area section of Redwood Regional Park.[75][76]

See also

- Bury Me in Redwood Country

- Save the Redwoods League

- Northern California coastal forests

- Pacific temperate rainforests

- Redwood (color)

- Stephen C. Sillett

References

- Farjon, A.; Schmid, R. (2013). "Sequoia sempervirens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T34051A2841558. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T34051A2841558.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- NatureServe. 2020. Sequoia sempervirens, Redwood. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.140518/Sequoia_sempervirens. Accessed 11 November 2021.

- Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

"sempervirent". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) - BSBI List 2007 (xls). Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- The related Sequoiadendron giganteum is commonly referred to as "giant redwood".

- "Sequoia gigantea is of an ancient and distinguished family". Nps.gov. 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "Redwood National & State Parks Redwood burl poaching background and update" (PDF). www.nps.gov. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Kreissman, Bern; Lekisch, Barbara (1991). California, an Environmental Atlas & Guide. Bear Klaw Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0962748998. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Hearings, Reports and Prints of the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. United States. Congress. House. Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. 31 January 1978. p. 266. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Watson, Frank D. (1993). "Sequoia sempervirens". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 2. New York and Oxford. Retrieved 1 February 2015 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Ahuja, MR; Neale, DB (2002). "Origins of Polyploidy in Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Relationship of Coast Redwood to other Genera of Taxodiaceae". Silvae Genetica. 51 (2–3): 93–100.

- Neale, DB; Marshall, KA; Sederoff, RR (1989). "Chloroplast and Mitochondrial DNA are Paternally Inherited in Sequoia sempervirens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 86 (23): 9347–9. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.9347N. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.23.9347. PMC 298492. PMID 16594091.

- Don, David (1824). Lambert, Aylmer Bourke (ed.). A description of the genus Pinus :illustrated with figures, directions relative to the cultivation, and remarks on the uses of the several species. Vol. 2. London, United Kingdom: J. White. p. 24.

- Endlicher, Stephan (1847). Synopsis Coniferarum. Vol. 1847. St. Gallen: Scheitlin & Zollikofer.

- Muleady-Mecham, Nancy E. (August 2017). "Endlicher and Sequoia: Determination of the Etymological Origin of the Taxon". Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences. 116 (2): 137–146. doi:10.3160/soca-116-02-137-146.1. S2CID 89925020.

- Yang, Z.Y.; Ran, J.H.; Wang, X.Q. (2012). "Three Genome-based Phylogeny of Cupressaceae s.l: Further Evidence for the Evolution of Gymnosperms and Southern Hemisphere Biogeography". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 64 (3): 452–470. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.05.004. PMID 22609823.

- Farjon, A. (2005). Monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 1-84246-068-4.

- "Redwood fog drip". Bio.net. 1998-12-02. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- Barlow, Connie. "CTL 9G - Coast Redwoods at Chetco River Oregon (VIDEO of 2019 site visit)". Youtube. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- "SPECIES: Sequoia sempervirens". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- "The Redwood Nature Trail, Siskiyou National Forest". www.redwoodhikes.com. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Coast Redwood : Los Padres ForestWatch". www.lpfw.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Photography on the Run: Calflora/Google Maps image of coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) distribution in California. The southernmost naturally-occurring coast redwoods are in Monterey County, in the Southern Redwood Botanical Area of Los Padres National Forest". photographyontherun.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Noss, Reed (2000). The Redwood Forest: History, Ecology, and Conservation of the Coast Redwoods. Island Press. ISBN 978-1559637268. OCLC 925183647.

- Earle, Christopher J., ed. (2018). "Sequoia sempervirens". The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved 2017-12-30.

- Becking, Rudolf Willem (1982-01-01). Pocket flora of the redwood forest. Island Press. ISBN 978-0933280021. OCLC 904189212.

- Shirely, James Clifford. 1940. The Redwoods of Coast and Sierra. University of California Press.

- Ramage, B.S.; OʼHara, K.L.; Caldwell, B.T. (2010). "The role of fire in the competitive dynamics of coast redwood forests". Ecosphere. 1 (6). article 20. doi:10.1890/ES10-00134.1.

- Stone, Edward C.; Vasey, Richard B. (January 12, 1968). "Preservation of Coast Redwoods on Alluvial Flats". Science. 159 (3811): 157–161. Bibcode:1968Sci...159..157S. doi:10.1126/science.159.3811.157. JSTOR 1723263. PMID 17792349.

- Harris, S. A. (1989). "Relationship of convection fog to characteristics of the vegetation of Redwood National Park". MSC Thesis.

- Koch, G.W.; Sillett, S.C.; Jennings, G.M.; Davis, S.D. (2004). "The limits to tree height". Nature. 428 (6985): 851–854. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..851K. doi:10.1038/nature02417. PMID 15103376. S2CID 11846291.

- Ishii, H. T.; Jennings, Gregory M.; Sillett, Stephen C.; Koch, George W. (July 2008). "Hydrostatic constraints on morphological exploitation of light in tall Sequoia sempervirens trees". Oecologia. 156 (4): 751–63. Bibcode:2008Oecol.156..751I. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1032-z. PMID 18392856. S2CID 20868469.

- Sperry, J. S.; Meinzer; McCulloh (May 2008). "Safety and efficiency conflicts in hydraulic architecture: scaling from tissues to trees. Plant". Plant, Cell & Environment. 31 (5): 632–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01765.x. PMID 18088335.

- Mullen, L. P.; Sillett, S. C.; Koch, G. W.; Antonie, K. P.; Antoine, M. E. (May 29, 2009). "Physiological consequences of height-related morphological variation in Sequoia sempervirens foliage" (PDF). Tree Physiology. 29 (8): 999–1010. doi:10.1093/treephys/tpp037. PMID 19483187. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2012.

- Ishii, H. T.; Azuma, Wakana; Kuroda, Keiko; Sillett, Stephen C. (May 26, 2014). "Pushing the limits to tree height: Could foliar water storage compensate for hydraulic constraints in sequoia sempervirens?". Functional Ecology. 28 (5): 1087–1093. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12284.

- Burgess, S. S. O.; Dawson, T. E. (2004). "The contribution of fog to the water relations of Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don): foliar uptake and prevention of dehydration". Plant, Cell and Environment. 27 (8): 1023–1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01207.x.

- Oldham, A. R.; Sillett, S. C.; Tomescu, A. M. F.; Koch, G. W. (July 2010). "The hydrostatic gradient, not light availability drives height-related variation in Sequoia sempervirens (Cupressaceae) leaf anatomy". American Journal of Botany. 97 (7): 1087–97. doi:10.3732/ajb.0900214. PMID 21616861.

- Dawson, T. E. (1 September 1998). "Fog in the California redwood forest: Ecosystem inputs and used by plants" (PDF). Oecologia. 117 (4): 476–485. Bibcode:1998Oecol.117..476D. doi:10.1007/s004420050683. PMID 28307672. S2CID 26820268.

- Simonin, K. A.; Santiago, Louis S.; Dawson, Todd E. (July 2009). "Fog interception by Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don) crowns decouples physiology from soil water deficit". Plant, Cell and Environment. 32 (7): 882–892. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01967.x. PMID 19302173.

- Earles, J. M.; Sperling, O.; Silva, L. C. R.; McElrone, A. J.; Brodersen, C. R.; North, M. P.; Zwieniecki, M. A. (2015). "Bark water uptake promotes localized hydraulic recovery in coastal redwood crown". Plant, Cell & Environment. 39 (2): 320–328. doi:10.1111/pce.12612. PMID 26178179.

- Tognetti, R. A.; Longobucco, Anna; Rashi, Antonio; Jones, Mike B. (2001). "Stem hydraulic properties and xylem vulnerability to embolism in three co-occurring Mediterranean shrubs at a natural CO2 spring". Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 28 (4): 257. doi:10.1071/PP00125.

- "Botanical Garden Logistics" (PDF). UC Berkeley – Biology 1B – Plants & Their Environments (p. 13). Berkeley, California: Department of Integrative Biology, University of California-Berkeley. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 22.

- Lowell, Phillip G. (1990). A Review of Redwood Harvesting: Another Look — 1990. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

- "Kia Ora - Welcome to The Redwoods Whakarewarewa Forest". Rotorua District Council. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- "Redwood History". The New Zealand Redwood Company. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "Distribution within Europe". Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- "Longhouse". Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- "RHS Plant Selector Sequoia sempervirens AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 96. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- Van Pelt, Robert (2001). Forest Giants of the Pacific Coast. Global Forest Society and University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98140-6.

- "Climate explains why West Coast trees are much taller than those in the East". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- Scientific American: Supplement. Munn and Company. 1877-01-01.

- Carder, A (1995). Forest giants of the world: past and present. Ontario: Fitzhenry and Whiteside. ISBN 978-1-55041-090-7.

- "Pacific Coast News". Lumber World Review. 27 (8): 41. 25 October 1914. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Redwood Lumber Industry, Lynwood Carranco. Golden West Books, 1982 - Page 21.

- "Fort Worth Daily Gazette, Fort Worth, Texas. December 9th, 1886 - Page 2". Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. 1886-12-09. p. 2. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "Does size matter? John Driscoll/The Times-Standard, Eureka, California. September 8th, 2006". Times-standard.com. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- "A Mendocino Big Tree". Mining and Scientific Press. 66 (15): 230. 15 April 1893. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "A Giant Redwood for the World's Fair". Pacific Rural Press. 45 (16): 354. 22 April 1893. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Notes". Garden and Forest. 6: 260. 14 June 1893. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Wendell D. Flint (1 January 2002). To Find the Biggest Tree. Sequoia Natural History Association. ISBN 978-1-878441-09-6.

- "Cotati residents, scientists scramble to save albino redwood". SFGate. 2014-03-19.

- Stienstra, T (2007-10-11). "It's no snow job: handful of redwoods are rare albinos". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- "Ghost Redwoods: Solving the Albino Redwoods Mystery". 28 September 2016.

- "Mystery Of White Trees Among California's Redwoods May Be Solved". NPR.

- "text report and photograph of premier redwood canopy scientist Dr. Stephen C. Sillett from Humboldt State University while measuring the National Geographic Tree ("Nugget") immediately adjacent to the Tall Trees Trail". 27 September 2014.

- National Park Service (1997). "The General Sherman Tree". Sequoia National Park. Washington, DC: National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2015-03-15. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Sequoia sempervirens (coast redwood) description". www.conifers.org. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "5 Largest and Tallest Trees in the World". 3 April 2019.

- "Alameda". California State Parks Office of Historic Preservation.

- "Crannell Creek Giant Coast Redwood. Lindsey Creek Giant Redwood. Largest Sequoia sempervirens Ever Recorded". www.mdvaden.com. Retrieved 2019-11-03.

- The Most Massive Tree, Zilkha Biomass Energy

- Herron Zamora, Jim (August 14, 2006). "The 'Grandfather' of Oakland's redwoods". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Fimrite, Peter (May 8, 2013). "Hidden Redwood is Remnant of Forest Giants". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Slack, Gordy (July 1, 2004). "In the Shadow of Giants". BayNature.

Further reading

- Noss, R. F., ed. (2000). The Redwood Forest: history, ecology and conservation of the Coast Redwood. Island Press, Washington, D.C. ISBN 1-55963-726-9.

External links

- Institute for Redwood Ecology Includes photo gallery, canopy views, epiphytes, and arboreal animals

- Gymnosperm Database

- US National Park Service Redwood

- Muir Woods National Monument

- Save the Redwoods League Non-profit organization: education, protection and restoration

- Sempervirens Fund Non-profit organization

- ICT Int. Gallery sensors installation by Dr. Stephen Sillett & team

- Coast Redwoods - Largest & Tallest Photos for largest and tallest Coast Redwoods and other information.

- "Science on the SPOT: Albino redwoods, ghosts of the forest". YouTube video from Quest. KQED. 2010-08-26. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- Redwood Timelapse California Redwoods, YouTube. This is a short film about the Coastal Redwoods of California.

- One Man’s Mission to Revive the Last Redwood Forests | Short Film Showcase, On YouTube by National Geographic. Published on 28 May 2016;

- "Redwood Forests - Lumber Felling & Milling 1940's". YouTube video from Historia - Bel99TV. 2013-02-02. Archived from the original on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- Humboldt Redwoods State Park (CA) Humboldt Redwoods Interpretive Association

- Preston, Richard. "Climbing the Redwoods" - 2/14-21/2005 New Yorker article about redwoods and climbing.

- More about Sequoia sempervirens

- Popular Mechanics, November 1943, Saga of the Redwoods