Carcharodontosaurus

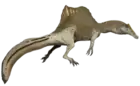

Carcharodontosaurus (/ˌkɑːrkəroʊˌdɒntoʊˈsɔːrəs/; lit. 'sharp-toothed lizard') is a genus of large carcharodontosaurid theropod dinosaur that existed during the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous in Northern Africa. The genus Carcharodontosaurus is named after the shark genus Carcharodon,[1] itself composed of the Greek karchar[os] (κάρχαρος, meaning "jagged" or "sharp") and odōn (ὀδών, "teeth"), and the suffix -saurus ("lizard"). It is currently known to have two species: C. saharicus and C. iguidensis.

| Carcharodontosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian), | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed C. saharicus skull, Science Museum of Minnesota | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Carcharodontosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Carcharodontosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Carcharodontosaurus Stromer, 1931 |

| Type species | |

| †Carcharodontosaurus saharicus Depéret & Savornin, 1925 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

History of discovery

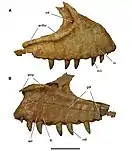

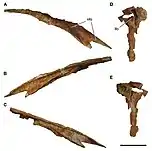

In 1924, two teeth were found in the Continental intercalaire of Algeria, showing what were at the time unique characteristics. These teeth were described by Depéret and Savornin (1925) as representing a new taxon, which they named Megalosaurus saharicus[2] and later categorized in the subgenus Dryptosaurus.[3] Some years later, paleontologist Ernst Stromer described the remains of a partial skull and skeleton from Cenomanian aged rocks in the Bahariya Formation of Egypt (Stromer, 1931);[1] originally excavated in 1914, the remains consisted of a partial skull, teeth, vertebrae, claw bones and assorted hip and leg bones.[1] The teeth in this new finding matched the characteristics of those described by Depéret and Savornin, which led to Stromer conserving the species name saharicus but finding it necessary to erect a new genus for this species, Carcharodontosaurus, for their similarities, in sharpness and serrations, to the teeth of Carcharodon (Great white shark).[1]

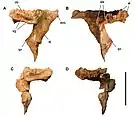

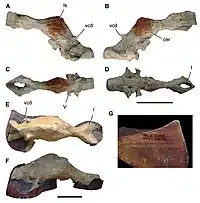

The fossils described by Stromer were destroyed in 1944 during World War II, but a new, more complete skull was found in the Kem Kem Group of Morocco during an expedition led by paleontologist Paul Sereno in 1995, near the Algerian border and the locality where the teeth described by Depéret and Savornin (1925) were found. The teeth found with this new skull matched those described by Depéret and Savornin (1925) and Stromer (1931); the rest of the skull also matched that described by Stromer. This new skull was designated as the neotype by Brusatte and Sereno (2007) who also described a second species of Carcharodontosaurus, C. iguidensis from the Echkar Formation of Niger, differing from C. saharicus in aspects of the maxilla and braincase.[4]

The taxonomy of Carcharodontosaurus was discussed in Chiarenza and Cau (2016),[5] who suggested that the neotype of C. saharicus was similar but distinct from the holotype in the morphology of the maxillary interdental plates. However, palaeontologist Mickey Mortimer put forward that the suggested difference between the C. saharicus neotype and holotype was actually due to damage to the neotype.[6] The authors also identified the referred material of C. iguidensis as belonging to Sigilmassasaurus and a non-carcharodontosaurine, and therefore chose to limit C. iguidensis to the holotype pending future research.[7]

Description

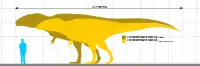

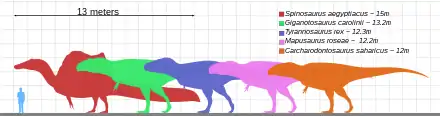

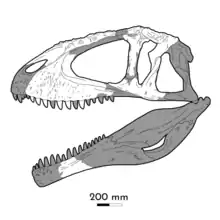

Carcharodontosaurus was one of the longest and heaviest known carnivorous dinosaurs, with an enormous 1.42–1.63 metres (4.7–5.3 ft) long skull and long, serrated teeth up to 8 in (20 cm) long.[8][9][10] C. saharicus reached 12–12.5 metres (39–41 ft) in length and approximately 6–6.2 metric tons (6.6–6.8 short tons) in body mass,[11][12][13][10] while C. iguidensis reached 10 metres (33 ft) in length and 4 metric tons (4.4 short tons) in body mass.[12]

Brain and inner ear

In 2001, Hans C. E. Larsson published a description of the inner ear and endocranium of Carcharodontosaurus saharicus.[14] Starting from the portion of the brain closest to the tip of the animal's snout is the forebrain, which is followed by the midbrain. The midbrain is angled downwards at a 45-degree angle and towards the rear of the animal. This is followed by the hindbrain, which is roughly parallel to the forebrain and forms a roughly 40-degree angle with the midbrain.[14] Overall, the brain of C. saharicus would have been similar to that of a related dinosaur, Allosaurus fragilis.[14] Larsson found that the ratio of the cerebrum to the volume of the brain overall in Carcharodontosaurus was typical for a non-avian reptile.[14] Carcharodontosaurus also had a large optic nerve.[14]

The three semicircular canals of the inner ear of Carcharodontosaurus saharicus – when viewed from the side – had a subtriangular outline.[14] This subtriangular inner ear configuration is present in Allosaurus, lizards, turtles, but not in birds.[14] The semi-"circular" canals themselves were actually very linear, which explains the pointed silhouette.[14] In life, the floccular lobe of the brain would have projected into the area surrounded by the semicircular canals, just like in other non-avian theropods, birds, and pterosaurs.[14]

Classification

The following cladogram after Apesteguía et al., 2016, shows the placement of Carcharodontosaurus within Carcharodontosauridae.[15]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Feeding

A study by Donald Henderson, the curator of dinosaurs at the Royal Tyrrell Museum suggests that Carcharodontosaurus was able to lift animals weighing a maximum of 424 kg (935 lb) in its jaws based on the strength of its jaws, neck, and its center of mass.[16][10]

Pathology

SGM-Din 1, a Carcharodontosaurus saharicus skull, has a circular puncture wound in the nasal and "an abnormal projection of bone on the antorbital rim."[17]

References

- Stromer, E. (1931). "Wirbeltiere-Reste der Baharijestufe (unterestes Canoman). Ein Skelett-Rest von Carcharodontosaurus nov. gen." Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung, 9(Neue Folge): 1–23.

- Deparet, C.; Savornin, J. (1925). "Sur la decouverte d'une faune de vertebres albiens a Timimoun (Sahara occidental)". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris. 181: 1108–1111.

- Deparet, C.; Savornin, J. (1927). "La faune de reptiles et de poisons albiens de Timimoun (Sahara algérien)". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 27: 257–265.

- Brusatte, S.L. and Sereno, P.C. (2007). "A new species of Carcharodontosaurus (dinosauria: theropoda) from the Cenomanian of Niger and a revision of the genus." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(4): .

- Chiarenza, Alfio Alessandro; Cau, Andrea (February 29, 2016). "A large abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco and comments on the Cenomanian theropods from North Africa". PeerJ. 4: e1754. doi:10.7717/peerj.1754. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4782726. PMID 26966675.

- Mortimer, Mickey. "Carcharodontosaurus saharicus". The Theropod Database.

- Chiarenza, Alfio Alessandro; Cau, Andrea (February 29, 2016). "A large abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco and comments on the Cenomanian theropods from North Africa". PeerJ. 4: e1754. doi:10.7717/peerj.1754. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4782726. PMID 26966675.

- Carrano, Matthew T.; Benson, Roger B. J.; Sampson, Scott D. (2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 85354215.

- Sereno, P. C.; Dutheil, D. B.; Iarochene, M.; Larsson, H. C. E.; Lyon, G. H.; Magwene, P. M.; Sidor, C. A.; Varricchio, D. J.; Wilson, J. A. (1996). "Predatory Dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous Faunal Differentiation". Science. 272 (5264): 986–991. Bibcode:1996Sci...272..986S. doi:10.1126/science.272.5264.986. PMID 8662584. S2CID 39658297.

- Henderson, D.M.; Nicholls, R. (2015). "Balance and Strength—Estimating the Maximum Prey-Lifting Potential of the Large Predatory Dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus saharicus". The Anatomical Record. 298 (8): 1367–1375. doi:10.1002/ar.23164. PMID 25884664. S2CID 19465614.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF).

Winter 2011 Appendix

- Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-78684-190-2. OCLC 985402380.

- Seebacher, F. (2001). "A New Method to Calculate Allometric Length-Mass Relationships of Dinosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.255. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 53446536.

- Larsson, H.C.E. 2001. Endocranial anatomy of Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) and its implications for theropod brain evolution. pp. 19–33. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Ed.s Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press.

- Sebastián Apesteguía; Nathan D. Smith; Rubén Juárez Valieri; Peter J. Makovicky (2016). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157793A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157793. PMC 4943716. PMID 27410683.

- "The Science Behind This Violent Dino Eiffel Tower is Revolutionary".

- "Acrocanthosauridae fam. nov.," in Molnar (2001). Pg. 342.