Casein

Casein (/ˈkeɪsiːn/ KAY-see-n, from Latin caseus "cheese") is a family of related phosphoproteins (αS1, aS2, β, κ) that are commonly found in mammalian milk, comprising about 80% of the proteins in cow's milk and between 20% and 60% of the proteins in human milk.[1] Sheep and buffalo milk have a higher casein content than other types of milk with human milk having a particularly low casein content.[2]

Casein has a wide variety of uses, from being a major component of cheese, to use as a food additive.[3] The most common form of casein is sodium caseinate.[4] In milk, casein undergoes phase separation to form colloidal casein micelles, a type of secreted biomolecular condensate.[5]

As a food source, casein supplies amino acids, carbohydrates, and two essential elements, calcium and phosphorus.[6]

Composition

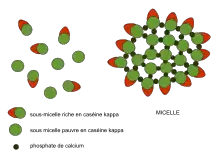

Casein contains a high number of proline amino acids which hinder the formation of common secondary structural motifs of proteins. There are also no disulfide bridges. As a result, it has relatively little tertiary structure. It is relatively hydrophobic, making it poorly soluble in water. It is found in milk as a suspension of particles, called casein micelles, which show only limited resemblance with surfactant-type micelles in a sense that the hydrophilic parts reside at the surface and they are spherical. However, in sharp contrast to surfactant micelles, the interior of a casein micelle is highly hydrated. The caseins in the micelles are held together by calcium ions and hydrophobic interactions. Any of several molecular models could account for the special conformation of casein in the micelles.[7] One of them proposes the micellar nucleus is formed by several submicelles, the periphery consisting of microvellosities of κ-casein.[8][9][10] Another model suggests the nucleus is formed by casein-interlinked fibrils.[11] Finally, the most recent model[12] proposes a double link among the caseins for gelling to take place. All three models consider micelles as colloidal particles formed by casein aggregates wrapped up in soluble κ-casein molecules.

The isoelectric point of casein is 4.6. Since milk's pH is 6.6, casein has a negative charge in milk. The purified protein is water-insoluble. While it is also insoluble in neutral salt solutions, it is readily dispersible in dilute alkalis and in salt solutions such as aqueous sodium oxalate and sodium acetate.

The enzyme trypsin can hydrolyze a phosphate-containing peptone. It is used to form a type of organic adhesive.[13]

Uses

Paint

Casein paint is a fast-drying, water-soluble medium used by artists. Casein paint has been used since ancient Egyptian times as a form of tempera paint, and was widely used by commercial illustrators as the material of choice until the late 1960s when, with the advent of acrylic paint, casein became less popular.[14][15] It is still widely used by scenic painters, although acrylic has made inroads in that field as well.[16]

Glue

Casein-based glues are formulated from casein, water, and alkalis (usually a mix of hydrated lime and sodium hydroxide). Milk is skimmed to remove the fat, then the milk is soured so that the casein is precipitated as milk curd. The curd is washed (removing the whey), and then the curd is pressed to squeeze out the water (it may even be dried to a powder). The casein is mixed with alkali (usually both sodium and calcium hydroxide) to make glue. Glues made with different mixes of alkalis have different properties. Preservatives may also be added.[17][18]

They were popular for woodworking, including for aircraft, as late as the de Havilland Albatross airliner in 1939.[19][20]

Casein glue is also used in transformer manufacturing (specifically transformer board) due to its oil permeability.[21]

Elmer's Glue-All, Elmer's School Glue and many other Borden adhesives were originally made from casein. While one reason was its non-toxic nature, a primary factor was that it was economical to use. Towards the end of the 20th century, Borden replaced casein in all of its popular adhesives with synthetics like PVA.

While largely replaced with synthetic resins, casein-based glues still have a use in certain niche applications, such as laminating fireproof doors and the labeling of bottles.[19][22][23][24] Casein glues thin rapidly with increasing temperature, making it easy to apply thin films quickly to label jars and bottles on a production line.[25]

Food

Several foods, creamers, and toppings all contain a variety of caseinates. Sodium caseinate acts as a greater food additive for stabilizing processed foods, however companies could opt to use calcium caseinate to increase calcium content and decrease sodium levels in their products.[26]

| Product | Caseinate % | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Meat | 2–20 | Texture and nutrition |

| Cheese | 3–28 | Matrix formation, fat, and water binding |

| Ice Cream | 1–7 | Texture and stabilizer |

| Whipped toppings | 2–11 | Fat stabilization |

| Pasta | 2–18 | Texture, nutrition, and taste |

| Baked goods | 1–15 | Water binding |

The main food uses of casein are for powders requiring rapid dispersion into water, ranging from coffee creamers to instant cream soups. Mead Johnson introduced a product in the early 1920s named Casec to ease gastrointestinal disorders and infant digestive problems which were a common cause of death in children at that time. It is believed to neutralize capsaicin, the active (hot) ingredient of peppers, jalapeños, habaneros, and other chili peppers.[28]

Cheesemaking

Cheese consists of proteins and fat from milk, usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep. It is produced by coagulation that is caused by destabilization of the casein micelle, which begins the processes of fractionation and selective concentration.[2] Typically, the milk is acidified and then coagulated by the addition of rennet, containing a proteolytic enzyme known as rennin; traditionally obtained from the stomachs of calves, but currently produced more often from genetically modified microorganisms. The solids are then separated and pressed into final form.[29]

Unlike many proteins, casein is not coagulated by heat. During the process of clotting, milk-clotting proteases act on the soluble portion of the caseins, κ-casein, thus originating an unstable micellar state that results in clot formation. When coagulated with chymosin, casein is sometimes called paracasein. Chymosin (EC 3.4.23.4) is an aspartic protease that specifically hydrolyzes the peptide bond in Phe105-Met106 of κ-casein, and is considered to be the most efficient protease for the cheese-making industry (Rao et al., 1998). British terminology, on the other hand, uses the term caseinogen for the uncoagulated protein and casein for the coagulated protein. As it exists in milk, it is a salt of calcium.

Protein supplements

An attractive property of the casein molecule is its ability to form a gel or clot in the stomach, which makes it very efficient in nutrient supply. The clot is able to provide a sustained slow release of amino acids into the blood stream, sometimes lasting for several hours.[30] Often casein is available as hydrolyzed casein, whereby it is hydrolyzed by a protease such as trypsin. Hydrolyzed forms are noted to taste bitter and such supplements are often refused by infants and lab animals in favor of intact casein.[31]

Plastics and fiber

Some of the earliest plastics were based on casein. In particular, galalith was well known for use in buttons. Fiber can be made from extruded casein. Lanital, a fabric made from casein fiber (known as Aralac in the United States), was particularly popular in Italy during the 1930s. Recent innovations such as QMILK are offering a more refined use of the fiber for modern fabrics.

Medical and dental uses

Casein-derived compounds are used in tooth remineralization products to stabilize amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) and release the ACP onto tooth surfaces, where it can facilitate remineralization.[32][33][34]

Casein and gluten exclusion diets are sometimes used in alternative medicine for children with autism. As of 2015 the evidence that such diets have any impact on behavior or cognitive and social functioning in autistic children was limited and weak.[35][36]

Nanotechnological uses

Casein proteins have potential for use as nanomaterials due to their readily available source (milk) and their propensity to self-assemble into amyloid fibrils.[37]

Potential health issues and adverse effects

A1/A2 beta caseins in milk

A1 and A2 beta-casein are genetic variants of the beta-casein milk protein that differ by one amino acid; a proline occurs at position 67 in the chain of amino acids that make up the A2 beta-casein, while in A1 beta-casein a histidine occurs at that position.[38][39] Due to the way that beta-casein interacts with enzymes found in the digestive system, A1 and A2 are processed differently by digestive enzymes, and a seven-amino peptide, beta-casomorphin-7, (BCM-7) can be released by digestion of A1-beta-casein.[38]

The A1 beta-casein type is the most common type found in cow's milk in Europe (excluding Italy and France which have more A2 cows), the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.[40]

Interest in the distinction between A1 and A2 beta-casein proteins began in the early 1990s through epidemiological research and animal studies initially conducted by scientists in New Zealand, which found correlations between the prevalence of milk with A1 beta-casein proteins and various chronic diseases.[38] The research generated interest in the media, among some in the scientific community, and entrepreneurs.[38] A company, A2 Corporation, was founded in New Zealand in the early 2000s to commercialize the test and market "A2 Milk" as premium milk that is healthier due to the lack of peptides from A1.[38] A2 Milk even petitioned the Food Standards Australia New Zealand regulatory authority to require a health warning on ordinary milk.[38]

Responding to public interest, the marketing of A2 milk, and the scientific evidence that had been published. An independent review published in 2005 also found no discernible difference between drinking A1 or A2 milk on the risk of contracting chronic diseases.[38] The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reviewed the scientific literature and published a review in 2009 found no identifiable relationship between chronic diseases and drinking milk with the A1 protein.[40]

Casein allergy

A small fraction of the population is allergic to casein.[41] Casein intolerance, also known as "milk protein intolerance" is experienced when the body cannot break down the proteins of casein.[42] The prevalence of casein allergy or intolerance ranges from 0.25 to 4.9% of young children.[43] Numbers for older children and adults are not known. A significant portion of those on the autism spectrum have an intolerance or allergy to casein protein into adulthood. This can be used by clinicians and dietitians to spot autism in those who may not present with traditional autistic traits.[44] A diet known as casein-free, gluten free (CFGF) is commonly practiced by these individuals after discovering their intolerance or allergy.

Casein that is heat-treated has been shown to be more allergenic and harder to digest when fed to infants.[45] Breast milk has not typically been shown to cause an allergic reaction, but should be administered to an infant with caution each time in case of adverse reaction from something the breastfeeding parent consumed that contained casein. Following a casein-free diet has been shown to improve outcomes of infants who are breastfed while allergic or intolerant to dairy protein.[46] Human breast milk has been proven to be the best food for an infant, and should be tried first where available.[47]

Supplementation of protease enzyme has been shown to help casein intolerant individuals digest the protein with minimal adverse reaction.[48]

See also

- Dairy

- K-casein

- Milk skin

- Protein quality

- Beta-lactoglobulin

References

- Kunz, C; Lönnerdal, B (1990). "Human-milk proteins: analysis of casein and casein subunits by anion-exchange chromatography, gel electrophoresis, and specific staining methods". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1093/ajcn/51.1.37. PMID 1688683.

- Robinson RK, ed. (2002). Dairy Microbiology Handbook: The Microbiology of Milk and Milk Products (3rd ed.). Wiley-Interscience. p. 3. ISBN 9780471385967.

- "Industrial Casein". National Casein Company. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012.

- Early R (1997). "Milk Concentrates and Milk Powders". The technology of dairy products (2nd ed.). London: Springer-Verlag. p. 295. ISBN 9780751403442.

- Farrell HM (1973). "Models for Casein Micelle Formation". Journal of Dairy Science. 56 (9): 1195–1206. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(73)85335-4. PMID 4593735.

- "Casein". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Columbia University. 2011.

- Dalgleish DG (1998). "Casein Micelles as Colloids: Surface Structures and Stabilities". J. Dairy Sci. 81 (11): 3013–8. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75865-5.

- Panouillé, M.; Durand, D.; Nicolai, T.; Larquet, E.; Boisset, N. (2005). "Aggregation and gelation of micellar casein particles". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 287: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2005.02.008. PMID 15914152.

- Walstra P (1979). "The voluminosity of bovine casein micelles and some of its implications". Journal of Dairy Research. 46 (2): 317–323. doi:10.1017/S0022029900017234. ISSN 1469-7629. PMID 469060. S2CID 222355860.

- Lucey JA (2002). "Formation and Physical Properties of Milk Protein Gels". J. Dairy Sci. 85 (2): 281–94. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74078-2. PMID 11913691.

- Holt C (1992). "Structure and Stability of Bovine Casein Micelles". In Anfinsen CB, Richards FM, Edsall JT, et al. (eds.). Advances in Protein Chemistry. Vol. 43. Academic Press. pp. 63–151. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60554-9. ISBN 9780120342433. PMID 1442324.

- Horne DS (1998). "Casein Interactions: Casting Light on the Black Boxes, the Structure in Dairy Products". International Dairy Journal. 8 (3): 171–7. doi:10.1016/S0958-6946(98)00040-5.

- "Turning milk into homemade moo glue". Cornell Center for Teaching Innovation. Ask A Scientist!. Cornell University. 24 Sep 1998. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 29 Sep 2011.

- Weiss D, Chace S, eds. (1979). Reader's Digest Crafts & Hobbies. Reader's Digest Association. pp. 223. ISBN 9780895770639.

- Ward GW, ed. (2008). "Acrylic painting". The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780195313918.

- Gloman CB, Napoli R (2007). Scenic Design And Lighting Techniques: A Basic Guide for Theatre. Taylor & Francis. pp. 281–2. ISBN 9780240808062.

- Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture, University of Wisconsin--Madison (April 1961). Casein glues : their manufacture, preparation, and application - Indiana State Library (PDF). Information Reviewed and Reaffirmed. Vol. 280. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- "Chemistry Casein Glue - Activity" (PDF).

- "Casein Glues: Their Manufacture, Preparation, and Application" (PDF). USDA. 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Shurtleff W, Aoyagi A (2004). "Pioneering Soy Protein Companies: I. F. Laucks, The Glidden Co., Rich Products, Gunther Products, Griffith Laboratories". soyinfocenter.com. Retrieved 3 Sep 2015.

- "Laminated Board". WICOR HOLDING AG. 2011. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 11 Oct 2012.

- Lambuth A (2006). "Soybean, Blood, and Casein Glues". In Tracton AA (ed.). Coatings Materials and Surface Coatings. CRC Press. pp. 19-7–19-11. ISBN 9781420044058.

- Forsyth RS (2004). "Waterborne Adhesives for Bottle Labeling". Tappi PLACE Division Conference. Atlanta, Ga.: TAPPI. p. 33. ISBN 1595100628. OCLC 57487618.

- Label Glues Archived November 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Casein glues". Adhesives.

- "Dairy Product Companies; "Micellar Casein for Corree Creamers and Other Dairy Products" in Patent Application Approval Process". Food Weekly News. Jan 2017. ProQuest 1857923972.

- El-Bakry M (2011). "Functional and Physicochemical Properties of Casein and its Use in Food and Non-Food Industrial Applications". Chemical Physics Research Journal. 4: 125–138. ProQuest 1707988596.

- Jacobs J. "What Is Calcium Caseinate?". LIVESTRONG.COM. Retrieved 7 Mar 2019.

- Fankhauser DB (2007). "Fankhauser's Cheese Page". Archived from the original on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 23 Sep 2007.

- Boirie Y, Dangin M, Gachon P, et al. (1997). "Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion". PNAS. 94 (26): 14930–5. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9414930B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.26.14930. PMC 25140. PMID 9405716.

- Field KL, Kimball BA, Mennella JA, et al. (2008). "Avoidance of hydrolyzed casein by mice". Physiol. Behav. 93 (1–2): 189–99. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.08.010. PMC 2254509. PMID 17900635.

- Louis Malcmacher (8 February 2011). "Enamel Remineralization: The Medical Model of Practicing multi Dentistry". Dentistry Today.

- Walker G, Cai F, Shen P, et al. (2006). "Increased remineralization of tooth enamel by milk containing added casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate". Journal of Dairy Research. 73 (1): 74–78. doi:10.1017/S0022029905001482. PMID 16433964. S2CID 43342264.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra A (2018). "Enhanced Remineralisation of Tooth Enamel Using Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Complex: A Review". International Journal of Clinical Preventive Dentistry. 14 (1): 1–10. doi:10.15236/ijcpd.2018.14.1.1.

- Lange KW, Hauser J, Reissmann A (2015). "Gluten-free and casein-free diets in the therapy of autism". Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 18 (6): 572–5. doi:10.1097/mco.0000000000000228. PMID 26418822. S2CID 271720.

- Millward C, Ferriter M, Calver S, et al. (2008). "Gluten- and casein-free diets for autistic spectrum disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Systematic Review) (2): CD003498. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003498.pub3. PMC 4164915. PMID 18425890.

- Ecroyd, Heath; Garvey, Megan; Thorn, David C.; Gerrard, Juliet A.; Carver, John A. (2013), Gerrard, Juliet A. (ed.), "Amyloid Fibrils from Readily Available Sources: Milk Casein and Lens Crystallin Proteins", Protein Nanotechnology, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, vol. 996, pp. 103–117, doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-354-1_6, ISBN 978-1-62703-353-4, PMID 23504420, retrieved 2020-10-17

- Truswell AS (2005). "The A2 milk case: a critical review". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 59 (5): 623–31. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602104. PMID 15867940.

- Truswell AS (2006). "Reply: The A2 milk case: a critical review". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 60 (7): 924–5. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602454.

- EFSA (2009). "Review of the potential health impact of β-casomorphins and related peptides: Review of the potential health impact of β-casomorphins and related peptides". EFSA Journal. 7 (2): 231r. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.231r.

- Solinas C, Corpino M, Maccioni R, et al. (2010). "Cow's milk protein allergy". J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 23 (Suppl 3): 76–9. doi:10.3109/14767058.2010.512103. PMID 20836734. S2CID 3189637.

- "Dairy Intolerance: What It Is and How to Determine If You Have It". Mark's Daily Apple. 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- "Cow's Milk Allergy in Children | World Allergy Organization". www.worldallergy.org. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- Sanctuary, Megan R.; Kain, Jennifer N.; Angkustsiri, Kathleen; German, J. Bruce (2018-05-18). "Dietary Considerations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: The Potential Role of Protein Digestion and Microbial Putrefaction in the Gut-Brain Axis". Frontiers in Nutrition. 5: 40. doi:10.3389/fnut.2018.00040. ISSN 2296-861X. PMC 5968124. PMID 29868601.

- Dupont, Didier; Mandalari, Giuseppina; Mollé, Daniel; Jardin, Julien; Rolet-Répécaud, Odile; Duboz, Gabriel; Léonil, Joëlle; Mills, Clare E. N.; Mackie, Alan R. (November 2010). "Food processing increases casein resistance to simulated infant digestion". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 54 (11): 1677–1689. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200900582. ISSN 1613-4133. PMID 20521278.

- "Infant Allergies and Food Sensitivities". HealthyChildren.org. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- "Breastfeeding". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- Christensen, L. R. (1954-11-01). "The action of proteolytic enzymes on casein proteins". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 53 (1): 128–137. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(54)90240-4. ISSN 0003-9861. PMID 13208290.

Further reading

- Green VA, Pituch KA, Itchon J, Choi A, O'Reilly M, Sigafoos J (2006). "Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism" (PDF). Res. Dev. Disabil. 27 (1): 70–84. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2004.12.002. PMID 15919178. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Lucarelli S, Frediani T, Zingoni AM, Ferruzzi F, Giardini O, Quintieri F, Barbato M, D'Eufemia P, Cardi E (1995). "Food allergy and infantile autism" (PDF). Panminerva Med. 37 (3): 137–41. PMID 8869369. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Rao MB, Tanksale AM, Ghatge MS, Deshpande VV (1998). "Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 (3): 597–635. doi:10.1128/MMBR.62.3.597-635.1998. PMC 98927. PMID 9729602.

- Manninen AH (2002). Protein metabolism in exercising humans with special reference to protein supplementation (PDF) (Master thesis). Finland: Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kuopio. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Demling RH, DeSanti L (2000). "Effect of a Hypocaloric Diet, Increased Protein Intake and Resistance Training on Lean Mass Gains and Fat Mass Loss in Overweight Police Officers". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 44 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1159/000012817. PMID 10838463. S2CID 3052747.

External links

- Caseins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Time magazine, Monday, December 6, 1936 Lanital

- Time magazine, Monday, August 29, 1938 Wool from Cows

- Structure of casein Mol-Instincts Chemical Database, Predicted on Quantum