Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585),[2] commonly known as Cassiodorus (/ˌkæsioʊˈdɔːrəs/), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. Senator was part of his surname; not his rank. He also founded a monastery, Vivarium, where he spent the last years of his life.[3]

Cassiodorus | |

|---|---|

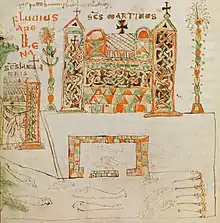

.jpg.webp) Cassiodorus (Gesta Theodorici: Leiden, University Library, Ms. vul. 46, fol. 2r), dated 1177 | |

| Layperson and Founder | |

| Born | Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator c. 490 Squillace, Catanzaro, Italy |

| Died | c. 583 (aged 92–93) Squillace, Catanzaro, Italy |

| Honored in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Major works | Monasteries of Vivarium and Montecastello |

Life

Cassiodorus was born at Scylletium, near Catanzaro in Calabria, Italy. Some modern historians speculate that his family was of Syrian origin based on his Greek name.[4][5] His ancestry included some of the most prominent ministers of the state extending back several generations.[6] His great-grandfather held a command in the defense of the coasts of southern Italy from Vandal sea-raiders in the middle of the fifth century; his grandfather appears in a Roman embassy to Attila the Hun, and his father (who bore the same name) served as comes sacrarum largitionum and comes rerum privatarum to Odovacer[6] and as Praetorian Prefect to Theoderic the Great.[7]

Cassiodorus began his career under the auspices of his father, about in his twentieth year, when the latter made him his consiliarius upon his own appointment to the Praetorian Prefecture. In the judicial capacity of the prefect, he held absolute right of appeal over any magistrate in the empire (or Gothic kingdom, later) and the consiliarius served as a sort of legal advisor in cases of greater complexity. Evidently, therefore, Cassiodorus had received some education in the law.[8] During his working life he worked as quaestor sacri palatii c. 507–511, as a consul in 514, then as magister officiorum under Theoderic, and later under the regency for Theoderic's young successor, Athalaric. Cassiodorus kept copious records and letterbooks concerning public affairs. At the Gothic court his literary skill, which seems mannered and rhetorical to modern readers, was so esteemed that when in Ravenna he was often entrusted with drafting significant public documents. His culminating appointment was as praetorian prefect for Italy, effectively the prime ministership of the Ostrogothic civil government[9] and a high honor to finish any career. Cassiodorus also collaborated with Pope Agapetus I in establishing a library of Greek and Latin texts which were intended to support a Christian school in Rome.

James O'Donnell notes:

[I]t is almost indisputable that he accepted advancement in 523 as the immediate successor of Boethius, who was then falling from grace after less than a year as magister officiorum, and who was sent to prison and later executed. In addition, Boethius' father-in-law (and step-father) Symmachus, by this time a distinguished elder statesman, followed Boethius to the block within a year. All this was a result of the worsening split between the ancient senatorial aristocracy centered in Rome and the adherents of Gothic rule at Ravenna. But to read Cassiodorus' Variae one would never suspect such goings-on.[10]

There is no mention in Cassiodorus' selection of official correspondence of the death of Boethius.

Athalaric died in early 534, and the remainder of Cassiodorus' public career was dominated by the Byzantine reconquest and dynastic intrigue among the Ostrogoths. His last letters were drafted in the name of Vitiges. Around 537–38, he left Italy for Constantinople, from where his successor was appointed, where he remained for almost two decades, concentrating on religious questions. He notably met Junillus, the quaestor of Justinian I there. His Constantinopolitan journey contributed to the improvement of his religious knowledge.

Cassiodorus spent his career trying to bridge the 6th-century cultural divides: between East and West, Greek culture and Latin, Roman and Goth, and between an orthodox people and their Arian rulers. He speaks fondly in his Institutiones of Dionysius Exiguus, the calculator of the Anno Domini era.

In his retirement, he founded the monastery of Vivarium[6] on his family estates on the shores of the Ionian Sea, and his writings turned to religion.

Monastery at Vivarium

Cassiodorus' Vivarium "monastery school"[11] was composed of two main buildings: a coenobitic monastery and a retreat, for those who desired a more solitary life. Both were located on the site of the modern Santa Maria de Vetere near Squillace. The twin structure of Vivarium was to permit coenobitic monks and hermits to coexist. The Vivarium appears not to have been governed by a strict monastic rule, such as that of the Benedictine Order. Rather Cassiodorus' work Institutiones was written to guide the monks' studies. To this end, the Institutiones focus largely on texts assumed to have been available in Vivarium's library. The Institutiones seem to have been composed over a lengthy period of time, from the 530s into the 550s, with redactions up to the time of Cassiodorus' death. Cassiodorus composed the Institutiones as a guide for introductory learning of both "divine" and "secular" writings, in place of his formerly planned Christian school in Rome:

I was moved by divine love to devise for you, with God's help, these introductory books to take the place of a teacher. Through them I believe that both the textual sequence of Holy Scripture and also a compact account of secular letters may, with God's grace, be revealed.[12]

The first section of the Institutiones deals with Christian texts, and was intended to be used in combination with the Expositio Psalmorum. The order of subjects in the second book of the Institutiones reflected what would become the Trivium and Quadrivium of medieval liberal arts: grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy. While he encouraged study of secular subjects, Cassiodorus clearly considered them useful primarily as aids to the study of divinity, much in the same manner as St. Augustine. Cassiodorus' Institutiones thus attempted to provide what Cassiodorus saw as a well-rounded education necessary for a learned Christian, all in uno corpore, as Cassiodorus put it.[13]

The library at Vivarium was still active c. 630, when the monks brought the relics of Saint Agathius from Constantinople, dedicating to him a spring-fed fountain shrine that still exists.[14] However, its books were later dispersed, the Codex Grandior of the Bible being purchased by the Anglo-Saxon Ceolfrith when he was in Italy in 679–80, and taken by him to Wearmouth Jarrow, where it served as the source for the copying of the Codex Amiatinus, which was then brought back to Italy by the now aged Ceolfrith.[15] Despite the demise of the Vivarium, Cassiodorus' work in compiling classical sources and presenting a sort of bibliography of resources would prove extremely influential in Late Antique Western Europe.[16]

Educational philosophy

Cassiodorus devoted much of his life to supporting education within the Christian community at large. When his proposed theological university in Rome was denied, he was forced to re-examine his entire approach to how material was learned and interpreted.[17] His Variae show that, like Augustine of Hippo, Cassiodorus viewed reading as a transformative act for the reader. It is with this in mind that he designed and mandated the course of studies at the Vivarium, which demanded an intense regimen of reading and meditation. By assigning a specific order of texts to be read, Cassiodorus hoped to create the discipline necessary within the reader to become a successful monk. The first work in this succession of texts would be the Psalms, with which the untrained reader would need to begin because of its appeal to emotion and temporal goods.[18] By examining the rate at which copies of his Psalmic commentaries were issued, it is fair to assess that, as the first work in his series, Cassiodorus's educational agenda had been implemented to some degree of success.[18]

Beyond demanding the pursuit of discipline among his students, Cassiodorus encouraged the study of the liberal arts. He believed these arts were part of the content of the Bible, and some mastery of them—especially grammar and rhetoric—necessary for a complete understanding of it.[18] These arts were divided into trivium (which included rhetoric, idioms, vocabulary and etymology) and quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. He also encouraged the Benedictine monks to study the medical texts of that era, the known herbals and texts of Hippocrates, Dioscorides and Galen.[19]

Classical connections

Cassiodorus is rivalled only by Boethius in his drive to preserve and explore classical literature during the 6th century AD.[20][21] He found the writings of the Greeks and Romans valuable for their expression of higher truths where other arts failed.[18] Though he saw these texts as vastly inferior to the perfect word of Scripture, the truths presented in them played to Cassiodorus' educational principles. Thus he is unafraid to cite Cicero alongside sacred text, and acknowledge the classical ideal of good being part of the practice of rhetoric.[18]

His love for classical thought also influenced his administration of Vivarium. Cassiodorus connected deeply with Christian neoplatonism, which saw beauty as concomitant with the Good. This inspired him to adjust his educational program to support the aesthetic enhancement of manuscripts within the monastery, something which had been practiced before, but not in the universality that he suggests.[22]

Classical learning would by no means replace the role of Scripture within the monastery; it was intended to augment the education already under way. It is also worth noting that all Greek and Roman works were heavily screened to ensure only proper exposure to text, fitting with the rest of the structured learning.[23]

Lasting impact

Cassiodorus' legacy is quietly profound. Before the founding of Vivarium, the copying of manuscripts had been a task reserved for either inexperienced or physically infirm devotees, and was performed at the whim of literate monks. Through the influence of Cassiodorus, the monastic system adopted a more vigorous, widespread, and regular approach to reproducing documents within the monastery.[24] This approach to the development of the monastic lifestyle was perpetuated especially through German religious institutions.[24]

This change in daily life also became associated with a higher purpose: the process was not merely associated with disciplinary habit, but also with the preservation of history.[25] During Cassiodorus' lifetime, theological study was on the decline and classical writings were disappearing. Even as the victorious Ostrogoth armies remained in the countryside, they continued to pillage and destroy Christian relics in Italy.[20] Cassiodorus' programme helped ensure that both classical and Christian literature were preserved through the Middle Ages.

Despite his contributions to monastic order, literature, and education, Cassiodorus' labors were not well acknowledged. After his death he was only partially recognized by historians of the age, including Bede, as an obscure supporter of the Church. In their descriptions of Cassiodorus, medieval scholars have been documented to change his name, profession, place of residence, and even his religion.[20] Some chapters from his works have been copied into other texts, suggesting that he may have been read, but not generally known.[23]

The works not assigned as a part of Cassiodorus' educational program must be examined critically. Because he had been working under the newly dominant power of the Ostrogoths, the writer demonstrably alters the narrative of history for the sake of protecting himself. The same could easily be said about his ideas, which were presented as non-threatening in their approach to peaceful meditation and its institutional isolationism.[26]

Works

- Laudes (very fragmentary published panegyrics on public occasions)

- Chronica (ending at 519), uniting all world history in one sequence of rulers, a union of Goth and Roman antecedents, flattering Goth sensibilities as the sequence neared the date of composition

- Gothic History (526–533), a lengthy and multi-volume work, survives only in Jordanes' abridgment Getica, which must be considered a separate work and is the only surviving ancient work about the Goths' early history

- Variae epistolae (537), Theoderic's state papers. Editio princeps by M. Accurius (1533). English translations by Thomas Hodgkin The Letters of Cassiodorus (1886); S.J.B. Barnish Cassiodorus: Variae (Liverpool: University Press, 1992) ISBN 0-85323-436-1

- Expositio psalmorum (Exposition of the Psalms)

- De anima ("On the Soul") (540)

- Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum (543–555)

- De artibus ac disciplinis liberalium litterarum ("On the Liberal Arts")

- Codex Grandior (a version of the Bible)

- De orthographia (c. 580), a compilation of the works of eight grammarians to act as a guide to proper spelling. It is the last known work by Cassiodorus, completed when he was 93 years old.[27][28]

- Historiae Ecclesiasticae Tripartitae Epitome co-produced with Epiphanius Scholasticus

See also

References

- "Pre-13th Century". Hagiography Circle. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- O'Donnell, James J. (1995). "Chronology". Cassiodorus.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cassiodorus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 459-460.

- Nicholson, Oliver (2018-04-19). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-256246-3.

- Christensen, Arne Søby (2002). Cassiodorus, Jordanes and the History of the Goths: Studies in a Migration Myth. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-710-3.

- Frassetto 2003, p. 103.

- Barnish, Samuel James Beeching. "Cassiodorus". Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.).

- Thomas Hodgkin, Letters Of Cassiodorus, (Oxford, 1886), introduction

- Cf., e.g., F. Denis de Sainte-Marthe: La vie de Cassiodore, chancelier et premier ministre de Theoderic le Grand. Paris 1694 (online, in French)

- "Cassiodorus: Chapter 1, Backgrounds and Some Dates". faculty.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- Jean Leclerq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, 2nd revised edition (New York: Fordham, Fordham University Press, 1977) 25.

- Institutions, trans. James W. Halporn and Mark Vessey, Cassiodorus: Institutions of Divine and Secular Learning and On the Soul, TTH 42 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2004)I.1, 105.

- Halporn and Vessey, Cassiodorus: Institutions, 68.

- Select Abstracts

- Maria Makepeace, http://www.florin.ms/pandect.html

- Halporn and Vessey, Cassiodorus: Institutions, 66.

- Wand, JWC. A History of the Early Church. Methuen & Co. Ltd. (Norwich: 1937)

- Astell, Ann W. (1999). "Cassiodorus's "Commentary on the Psalms" as an "Ars Rhetorica"". Rhetorica. XVII (Winter, 1999): 37–73. doi:10.1525/rh.1999.17.1.37.

- Deming, David (2012). Science and Technology in World History. McFarland. p. 87.

- Jones, Leslie W. (1945). "The Influence of Cassiodorus on Medieval Culture". Speculum. XX (October, 1945): 433–442. doi:10.2307/2856740. JSTOR 2856740. S2CID 162038478.

- General Audience of Pope Benedict XVI, Boethius and Cassiodorus. Internet. Available from "General Audience of Pope Benedict XVI, 12 March 2008". Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2008-04-30.; accessed June 21, 2011.

- "Cassiodorus' Institutes and Christian Book Selection". The Journal of Library History. I (April, 1966): 89–100.

- "The Value and Influence of Cassiodorus's Ecclesiastical History". The Harvard Theological Review. XLI (January, 1948): 51–67.

- Rand, E. K. (1938). "The New Cassiodorus by EK Rand". Speculum. XIII (October, 1938): 433–447. doi:10.2307/2849664. JSTOR 2849664. S2CID 161690186.

- Pergoli Campanelli, Alessandro (2013). Cassiodoro alle origini dell'idea di restauro. Milano: Jaca Book. p. 140. ISBN 978-88-16-41207-1.

- "Cassiodorus as Patricius and ex Patricio". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. XLI (1990): 499–503.

- O'Donnell, James J. (1995). "Cassiodorus – Chapter 7: Old Age and Afterlives". Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- "Cassiodorus | Historian, Statesman, and Monk". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

Sources

- Barnish, S.J. Roman Responses to an Unstable World: Cassiodorus' Variae in Context in: Vivarium in Context 7–22 (Centre Leonard Boyle: Vicenza 2008). ISBN 978-88-902035-2-7

- Cassiodorus, Flavius Magnus Aurelius (780). "Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum". Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc.Patr. 61, fol. 1v–67v. Southern Italy. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Cassiodorus, Flavius Magnus Aurelius (1167). "Gesta Theodorici". Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Ms. vul. 46. Fulda. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-263-9.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2015). "Late Antique Dalmatia and Pannonia in Cassiodorus' Variae". Povijesni Prilozi. 49: 9–80.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2016). "Late Antique Dalmatia and Pannonia in Cassiodorus' Variae (Addenda)". Povijesni Prilozi. 50: 191–198.

- O'Donnell, James J. (1969). Cassiodorus University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- O'Donnell, James J. (1979 and 1995). Cassiodorus (Berkeley: University of California Press). Online e-text, 1995 Post-Print.

External links

- Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon life, works, critical editions, translations and comprehensive bibliography on Cassiodorus.

- James J. O'Donnell's Cassiodorus webpage: an assessment of Cassiodorus' cultural predicament

- Works by Cassiodorus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Cassiodorus at Internet Archive

- Opera omnia vol. 1, Joannes Garetius, ed., Rouen, 1679. (Google Books)

- Opera omnia vol. 2, Joannes Garetius, ed., Rouen, 1679. (Google Books)

- History of the Christian Church/A.D. 590–1073 by Philip Schaff at 'ccel.org'

- History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire — Volume 4 by Gibbon at Project Gutenberg.

- Cassiodorus – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Site of the Vivarium of Cassiodorus – An account of survey and recognition at the proposed archaeological site of Vivarium (Coscia di Staletti', Catanzaro, Calabria).

- Societas internationalis pro Vivario for the study of Cassiodorus and his times

- The fountain of Cassiodorus A spring situated at the Coscia di Staletti on the grounds of the monastery of Cassiodorus, with a grotto, formerly a site of pagan worship and eventually Christianized by the addition of two large crosses.

- Vivarium in Context. Book description and reviews of the essays by Sam J. Barnish and Lellia Cracco Ruggini.