Amiens Cathedral

The Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Amiens (French: Basilique Cathédrale Notre-Dame d'Amiens), or simply Amiens Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic church. The cathedral is the seat of the Bishop of Amiens. It is situated on a slight ridge overlooking the River Somme in Amiens, the administrative capital of the Picardy region of France, some 120 kilometres (75 miles) north of Paris.

| Amiens Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Our Lady of Amiens | |

French: Notre-Dame d'Amiens | |

.JPG.webp) Amiens Cathedral | |

Amiens Cathedral | |

| 49°53′42″N 2°18′08″E | |

| Location | Amiens |

| Country | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Relics held | Alleged head of John the Baptist |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | Robert of Luzarches Thomas and Regnault de Cormont[1] |

| Style | High Gothic |

| Years built | c. 1220–1270 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 145 m (476 ft) |

| Width | 70 m (230 ft) |

| Nave width | 14.60 m (47.9 ft)[2] |

| Height | 42.30 m (138.8 ft) |

| Other dimensions | Façade: NW |

| Floor area | 7,700 square meters |

| Number of spires | 1 |

| Spire height | 112.70 m (369.8 ft)[2] |

| Administration | |

| Province | Reims |

| Diocese | Amiens |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Bishop Gérard Le Stang[3] |

| Official name | Amiens Cathedral |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii |

| Designated | 1981[4] |

| Reference no. | 162 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Session | 5th |

| Official name | Cathédrale Notre-Dame |

| Designated | 1862 |

| Reference no. | PA00116046[1] |

| Denomination | Église |

The cathedral was built almost entirely between 1220 and c. 1270, a remarkably short period of time for a Gothic cathedral, giving it an unusual unity of style. Amiens is a classic example of the High Gothic style of Gothic architecture. [5] It also has some features of the later Rayonnant style in the enlarged high windows of the choir, added in the mid-1250s.[5]

Its builders were trying to maximize the internal dimensions in order to reach for the heavens and bring in more light. As a result, Amiens Cathedral is the largest in France,[6] 200,000 cubic metres (260,000 cu yd), large enough to contain two cathedrals the size of Notre Dame of Paris.[7]

The cathedral has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981.[8] Although it has lost much of its original stained glass, Amiens Cathedral is renowned for the quality and quantity of early 13th-century Gothic sculpture in the main west façade and the south transept portal, and a large quantity of polychrome sculpture from later periods inside the building.

History

Earlier cathedrals

According to local tradition, Christianity was brought to Amiens in the third century A.D. by two Christian martyrs, known as Firmin the Martyr and Firmin the Confessor. Saint Martin was baptised in Amiens in 334. The church was suppressed by the invasions of the Vandals, and did not recommence until the end of the fifth century, with the baptism of Clovis I in 498 or 499. The first Bishop of Amiens was Edibus, who participated in a Council in 511. An early cathedral with two churches dedicated to the two Fermins is said in documents to have existed on the site of the present church, but there is no archaeological evidence.[9] Salvius, bishop of Amiens around 600, is credited with building this cathedral, but his Life is of very dubious accuracy.[10]

A fire destroyed the two churches and much of the town, and a Romanesque cathedral was built to replace it between 1137 and 1152. This cathedral hosted the wedding in 1193 of King Philip II of France. In 1206 Amiens received a celebrated relic, the reputed head of John the Baptist, purchased in Constantinople. This relic made Amiens a major pilgrimage destination, and gave it an important source of revenue (The reliquary was destroyed during the French Revolution but a recreation made in 1876 by a Paris jeweler, using some of the original rock crystal, is displayed today in the cathedral treasury).[9]

Construction

Exterior of Amiens Cathedral

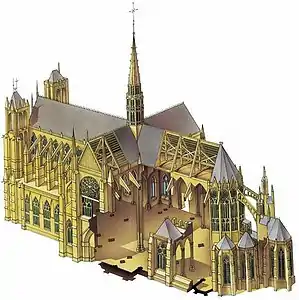

Exterior of Amiens Cathedral Cutaway plan of the cathedral

Cutaway plan of the cathedral

A fire destroyed the Romanesque cathedral in 1218. A plan for a new cathedral was made by master-builder Robert de Luzarches, and in 1220 Bishop Evrard de Fouilloy laid the first stone.[11] Luzarches revolutionised the system of Gothic construction by using pieces of stone of standardised sizes and forms, rather than making unique pieces for each function.[11] He was the architect until 1228, and was followed by Thomas de Cormont until 1258. His son, Renaud de Cormont, acted as the architect until 1288.[11]

The construction was carried out, unusually, from the west to the east, beginning in the nave. De Cormont gave the structure its striking dimensions and harmony by his construction of the grand arcades and the upper windows. The nave was completed in 1236, and by 1269, the upper windows of the choir were in place. At the end of the 13th century, the arms of the transept were completed, and in the beginning of the 14th century the facades and the upper towers were finished. While these works underway, the chapels between the buttresses and at the angles of the transept were added.[12]

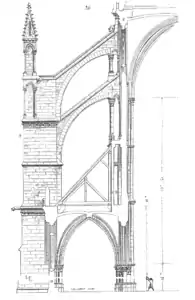

Strengthening (15th century)

The original design of the flying buttresses around the choir had them placed too high to counteract the force of the ceiling arch pushing outwards resulting in excessive lateral forces being placed on the vertical columns. The structure was only saved when masons placed a second row of more robust flying buttresses that connected lower down on the outer wall.[13]

In 1497 the four pillars of the transept crossing, as well as the two left columns of the chevet began to show cracks and other signs of stress. A team of experts examined the damage and carried out some repairs, but the cracks continued. The problem was finally resolved by the Pierre Tarisel, who in 1498 installed a wrought iron bar chain around the level to resist the forces pushing the stone columns outward. The chain was installed red hot to act as a cinch, tightening as it cooled, and is still in place.[13] In 1503 Tarisel took similar actions to reinforce portions of the entrance of the choir.[14]

Modifications (16–18th century)

The Flamboyant south rose window (16th c.)

The Flamboyant south rose window (16th c.)

In the 16th century, the cathedral suffered damage from fires, windstorms, and the explosion of a nearby powder mill, without major damage. It also underwent several modifications to accommodate changing styles; a new rose window, in the Flamboyant Gothic style, full of curls and counter-curls, was installed in the west transept. In the 18th century, architectural modifications were made to comply with new doctrines pronounced by the Council of Trent. The old medieval rood screen between the choir and nave was replaced by an ornate iron grill choir screen, so that the parishioners in the nave could see the altar. The altar itself was modified, removing the twelve massive candelabras and twelve chests of relics of martyred saints. Major works were also carried out to strengthen the flying buttresses.[15]

The Revolution and the 19th century

Interior of the cathedral by David Roberts (c. 1827)

Interior of the cathedral by David Roberts (c. 1827) Interior of the cathedral by Jules Victor Genisson (1842)

Interior of the cathedral by Jules Victor Genisson (1842) Sepia photograph of the cathedral in 1878

Sepia photograph of the cathedral in 1878

The cathedral, like other cathedrals across France, suffered considerable damage during the French Revolution. Much of the sculpture was smashed with hammers, and the heads of many statues were broken off. Many of the furnishings, fittings and treasures were stollen; part of the cathedral was used as a storehouse for materials used in various Revolutionary celebrations.[16]

The cathedral was returned to its religious function in 1800, and the first restoration work began in 1802.[16] Beginning in 1810, the neoclassical architect Etienne Hyppolyte Godde was put in charge of the work, followed in 1821 by Francois Auguste Cheussey, who commissioned three sculptors to make new statues. After the press criticized faults in the sculpture and restoration, Cheussey resigned and was replaced in 1849 by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Viollet-le-Duc began a more ambitious program aimed at returning the building as much as possible to its medieval spirit, including adding sculpted gargoyles and other typical Gothic features. Viollet-le-Duc worked almost continually on the cathedral until 1874.[15]

Protection and restoration (20th century)

.jpg.webp)

The stained glass windows of the church were removed to protect them during both the First and Second World War, and the church suffered only minor damage. However, in 1920, some of the windows, which were being stored in the workshop of a master glass maker, for their protection, were destroyed by a fire.

Between 1973 and 1980, the flèche, or spire, was entirely restored. In 1981, the cathedral was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Restoration of the west facade was completed in 2001. In 1992, the art historian Stephen Murray was appointed by the French Ministry of Culture in the scientific committee to oversee the restoration of Amiens Cathedral: Murray was made an honorary citizen of Amiens and awarded an honorary Doctorate at University of Picardy, Jules Verne, following this work.[17][18][19]

Timeline

- 346 – First mention of a bishop, Eulogius, in Amiens[20]

- 1137–52 – Construction of the Romanesque cathedral

- 1206 – Reputed Skull of Saint John the Baptist is brought to the cathedral from Constantinople

- 1218 – Romanesque cathedral destroyed by fire

- 1220 – First stone placed of Gothic cathedral

- c. 1240 – Completion of the nave

- c. 1269 – Probable completion of chevet and installation of its high windows

- c. 1284–1305 – Roof built over chevet, transept and nave

- 1373–1375 – Chapels of Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist built, and construction of Beau Pilier begun

- 1498 – Iron chains added to strengthen the triforium

- 1508–1519 – Choir stalls put in place

- 1528 – Spire destroyed by lightning

- 1755- Choir screen removed and choir remodeled following decrees of Council of Trent

- 1766–1768 – Choir redecorated in Baroque and French classical style

- 1793–1794 – Following French Revolution, much furniture destroyed, and part of cathedral used to store decorations for public festivities

- 1802 – Church restored to the Catholic Church for its exclusive use

- 1805 – Restoration of church begins

- 1849–1874 – Eugène Viollet-le-Duc supervises the restoration of the cathedral

- 1854 – Chapel of Saint Theodosius dedicated in presence of Emperor Napoleon III

- 1914–1918 – Stained glass removed for its protection; cathedral facade suffers minor damage during World War I

- 1920 – Some of the Gothic stained glass stored for protection is destroyed in a fire in the workshop.

- 1973–80 – Restoration of the spire completed.

- 1981 – Cathedral is declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- 2001 – A new restoration of the west front uncovers traces of the original painting on the sculpture

Exterior

The west facade and the portals

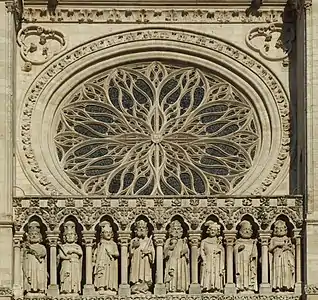

The rose window and gallery of Kings on the west facade

The rose window and gallery of Kings on the west facade West portals of Amiens Cathedral

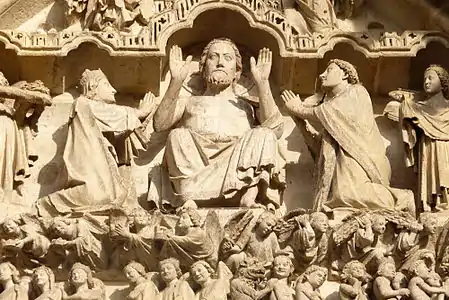

West portals of Amiens Cathedral Christ rendering judgement in the central portal

Christ rendering judgement in the central portal Local saints including the decapitated martyrs, Victoricus and Gentian, in the west portals

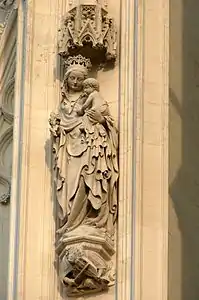

Local saints including the decapitated martyrs, Victoricus and Gentian, in the west portals Smiling Virgin statue on west portal

Smiling Virgin statue on west portal

The west facade of the cathedral was built in a single campaign from 1220 to 1236, and shows an unusual degree of artistic unity. The level of the rose window was finished in about 1240. Afterward, construction moved more slowly. The upper parts of the towers were not completed until the 14th century.[12]

The facade has three deep porches with pointed arches, covering the three portals. Above the portals are two galleries; the upper is the Gallery of Kings, with twenty-two life-size statues of the kings of France. Nearly all of the statues date to the restoration by Viollet-le-Duc. Above the gallery is the rose window, whose stone tracery or framework dates from the 16th century. Above the rose window is the Musicians or Bellringers gallery, a 19th-century reconstruction of the original.

The central portal is dedicated to the Last Judgement, the left portal to the martyr Saint Firmin; and the right portal to the Virgin Mary. Over each portal is a tympanum filled with sculpture. The centerpiece of the Tympanum of the Last Judgement is the figure of Christ, raising his hands, judging those below him. On his right and left, the Virgin Mary and Saint John appeal to him to be merciful. The good Christians, to his right, are escorted to Paradise, while the sinners, to his left, are marched to hell. A recent cleaning of the sculpture revealed traces of the painted red marks on Christ's hands, representing where nails were driven during his crucifixion.[21]

Statues of saints in the tympanum include locally venerated Saints Victoricus and Gentian, Saint Domitius, Saint Ulphia, and Saint Fermin.[22]

Bell towers

The upper portions of the towers of the west facade, above the rose window, were later constructions, and are of different heights. The south bell tower on the right facing the facade, is shorter and was completed first in about 1366, The north tower was completed in 1406, and is decorated in the late Gothic Flamboyant style.[23] The elaborate Bell-Ringers or Musicians Gallery, which joins the two towers at the roof level, was added at this time, and was substantially restored or recreated in the 19th century by Viollet-le-Duc. Viollet-le-Duc redesigned the gallery on the model of the gallery of Chartres Cathedral from the same period.[24]

The flamboyant north tower (c. 1406) and the south tower (c. 1366)

The flamboyant north tower (c. 1406) and the south tower (c. 1366) The south tower, with a sundial on the left

The south tower, with a sundial on the left

Beau Pilier

One unusual feature of the towers is the Beau Pilier (Beautiful pillar), a supporting buttress that was added in the 14th century at the junction between the north tower the first of two new chapels built on the north side. The pillar and chapels were commissioned by Jean de la Grange, Bishop of Amiens (1373–1375) who was a principal advisor to King Charles VI of France.

The pillar holds nine statues representing the major political, religious and military figures of France at the time; at the bottom, Cardinal de la Grange himself; The Chamberlain, Bureau de la Riviere, and Admiral Jean de Vienne, above them, King Charles himself (Centre); his son the Dauphin, the future King Charles VI of France, and his younger son. Above these statues are statues of John the Baptist, The Virgin Mary, and Saint Firmin. [25]

King Charles I of France, on the Beau Pilier (14th c.)

King Charles I of France, on the Beau Pilier (14th c.) Sculpture on the Beau Pilier – St, John the Baptist (14th c.)

Sculpture on the Beau Pilier – St, John the Baptist (14th c.) The Virgin Mary on the Beau Pilier (14th c.)

The Virgin Mary on the Beau Pilier (14th c.)

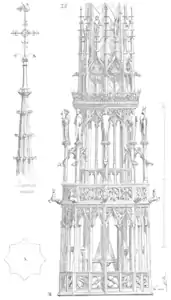

The flèche

The original 13th-century flèche, or spire of the cathedral, located over the crossing point of the transept and nave, was destroyed by lightning in 1528, but was replaced by a flèche constructed of wood covered with gilded lead plates. It was frequently damaged by storms and repaired in the following years but, unlike the flèche of Notre Dame de Paris, never entirely redesigned and rebuilt. It still retains much original 16th century material, including the wooden framework.[26] From the ground to sculpted cockerel at the pinnacle, the flèche reaches a height of 112.70 m (369.8 ft).[2]

The statues on the flèche, made of lead, represent Christ (facing the nave); Saint Paul, Saint Firmin (wearing a Bishop's mitre); Saint John the Evangelist; The Virgin Mary crowned and holding the infant Jesus; Saint John the Baptist; Saint James the Great and Saint Peter.

The flèche as drawn by Viollet-le-Duc

The flèche as drawn by Viollet-le-Duc The flèche of Amiens Cathedral (16th c.)

The flèche of Amiens Cathedral (16th c.) Sculpture of the flèche

Sculpture of the flèche

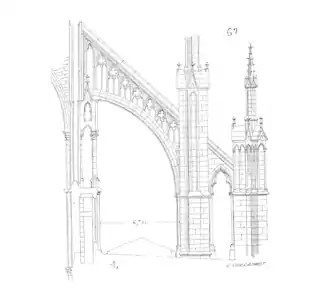

Flying buttresses

The flying buttresses are the architectural device that made possible the exceptional height of the walls of the nave and choir. The arched buttresses leap over the outer, lower level of the cathedral, where the ambulatory and chapels are located, to stabilise the upper walls of the clerestory. They counteract the outward and downward thrust of the vaulted ceiling, so that the walls between the buttresses can be thin and mostly filled with large windows. The buttresses were later given additional stability by the placement of heavy stone pinnacles on top of their vertical piers.[27] The buttresses of the nave are older, from about 1230, and each pier has two arches, one above the other. Both make a single jump to the wall of the nave; one arch meets the wall just above the point of maximum outward thrust from the nave vault; the other just below that point.

The buttresses of the choir are slightly later and were finished about 1260, to a different design. Each buttress has two vertical piers, one taller than the other, and the arches reach the wall by means of two vaults, meeting it at the point of maximum outward thrust. These choir buttresses have an additional function; channels in the top of the arches carry rain water as far as possible from the structure, jetting it out from the mouths of carved gargoyles.

The flying buttresses between the bays supporting the upper walls of the choir

The flying buttresses between the bays supporting the upper walls of the choir The early buttresses (c. 1230) of the nave, drawn by Viollet-Le-Duc in the 19th cent.

The early buttresses (c. 1230) of the nave, drawn by Viollet-Le-Duc in the 19th cent. The later reinforced double buttresses of the choir (c. 1260)

The later reinforced double buttresses of the choir (c. 1260)

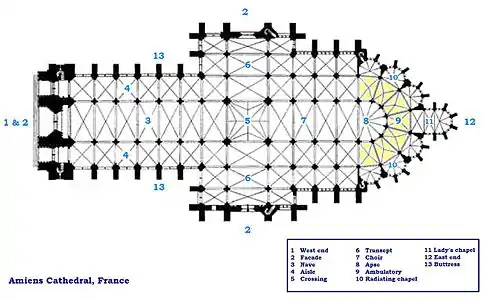

Interior

Plan of Cathedral

Plan of Cathedral

The nave

The nave and the transept were the areas where the public worshiped, while the choir was reserved for clergy. At Amiens, the Nave followed the model of the Early Gothic Chartres Cathedral and Soissons Cathedral. The elevation has three levels; the grand arcades, the triforium, and the clerestory at the top. The grand arcades, unlike earlier cathedrals, occupy a full half of the height of the wall. The pillars of the arcade, eighteen meters high, are composed of massive columns surrounded by four thinner colonettes, which continue up the walls to support the vaulted ceiling. The total height of the walls beneath the vaults is 42 meters, compared with 36 meters at Chartres Cathedral and Reims Cathedral. They are exceeded in height only by Beauvais Cathedral, whose vaults partially collapsed in 1284.[28]

The Baroque pulpit and the nave

The Baroque pulpit and the nave The upper windows of the nave

The upper windows of the nave

The pulpit

The Baroque pulpit on the north side of the nave was installed in 1773 and is made of painted and gilded wood. The pulpit is supported by statues representing Faith, Hope and Charity. Behind the pulpit gilded stone drapery. The tester is carved to resemble clouds supported by stone angels. Atop the "clouds" is a larger angel, pointing heavenwards, holding a book with the inscription, Hoc fac et vives (Do this and you shall live).[29]

The Baroque pulpit

The Baroque pulpit Detail of the pulpit; Faith, Hope, and Charity

Detail of the pulpit; Faith, Hope, and Charity The angel atop the Pulpit

The angel atop the Pulpit

The transept

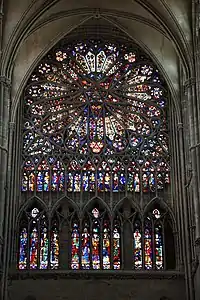

The transept crossing the church in the center is seventy meters long, and divided into three vessels. The centre of the transept, where it crosses the nave, is covered by a massive star vault, one of the earliest in France, supported by four massive pillars. The elevation has three levels, like the nave; the arcades, triforium and the clerestory at the top. The triforium and the clerestory are entirely walled with stained glass, filling the center of the cathedral with light.[30] The rose windows are later additions. The north rose window is in the Rayonnant style, while the later south rose window is in the Flamboyant style. The spire over the central crossing was added between 1529 and 1533.[2]

Transept and north stained glass windows

Transept and north stained glass windows The star vault of the transept, where it meets the nave

The star vault of the transept, where it meets the nave South transept rose window (16th century)

South transept rose window (16th century)

The choir

The early 16th century choir stalls, are among the great treasures of the cathedral. The upper rows were occupied by the Canons and the lower by the Clerks. The King's representative occupied the first seat in the north stalls, and the dean of the cathedral, the senior clergyman, the first seat in the south stalls.[31]

The stalls are decorated with a multitude of carved figures, more than four thousand in total. The armrests, pendentives and dais are also richly decorated with sculpted images of animals both real and mythical, figures from the Old and New Testaments and secular images of professions and trades in the city. One hundred ten of the original one hundred twenty stalls are the original 16th century fabric and carving.[31]

The choir and choir stalls, facing east to the apse

The choir and choir stalls, facing east to the apse The choir stalls

The choir stalls Detail of the choir stall carvings – the Assumption

Detail of the choir stall carvings – the Assumption

The ambulatory surrounding the choir is richly decorated with polychrome sculpture and flanked by numerous chapels. One of the most sumptuous is the Drapers' chapel. The cloth industry was the most dynamic component of the medieval economy, especially in northern France, and the cloth merchants were keen to display their wealth and civic pride. Another striking chapel is dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury, a 13th-century dedication that complements the cathedral's own very full list of martyrs.

The interior contains works of art and decoration from every period since the building of the cathedral. There are notably baroque paintings of the 17th century, by artists such as Frans II Francken and Laurent de La Hyre.

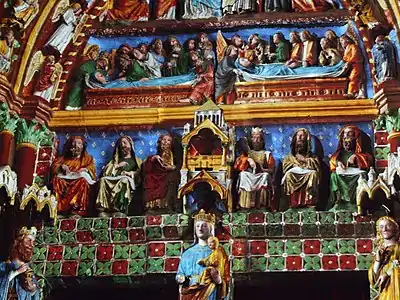

The Choir screen (15th–16th c.)

Among the most celebrated art treasures of the cathedral are the polychrome sculptures which are displayed in the ambulatory, on the outer walls of the enclosure of the Choir. They illustrate the lives of Saint Fermin (south side, made between 1490 and 1530) and John the Baptist (north side, made in 1531)). Both subjects were connected with the cathedral; The purported head of John the Baptist was an important relic held in the treasury, and the martyred Saint Fermin was considered the first bishop of Amiens. Another group of polychrome sculpture in the north ambulatory depicts in imaginative fashion Christ's cleansing of the Temple. The tombs of several bishops and other religious figures of the cathedral, also abundantly decorated are found in the lower portions of the enclosure, below the sculptural scenes.[32]

Scenes from the life of St. Firmin and the tomb of Bishop Ferry de Beauvoir (1490–1530)

Scenes from the life of St. Firmin and the tomb of Bishop Ferry de Beauvoir (1490–1530) A scene from the life of Saint Firmin

A scene from the life of Saint Firmin

The altar

In the mid-18th century the centre of the cathedral was entirely redesigned in the Roccoco style, to follow changes in church doctrine ordained by the Council of Trent and changing architectural taste. A new floor of coloured marble was installed, along with a new main altar. In 1768 the "Gloire", a monumental Baroque screen of sculpted and gilded wood representing heaven and crowded with sculpture of cherubs and angel was placed behind the altar. [33]

Detail of the Baroque choir grill (18th c.)

Detail of the Baroque choir grill (18th c.) The baroque high altar and "Gloire" screen (1755–68)

The baroque high altar and "Gloire" screen (1755–68) Detail of the "Gloire" screen

Detail of the "Gloire" screen

The labyrinth

A labyrinth in the centre of the floor of the nave was a common feature of early and High Gothic cathedrals; they were also found in the cathedrals of Sens, Chartres, Arras and Reims. It symbolised the obstacles and twists and turns of the journey toward salvation, but also showed that with determination the journey was possible. On certain religious holidays, pilgrims would follow the labyrinth on their knees. The Amiens labyrinth is 240 meters long and was originally laid out in 1288 by the architect Rene de Cormont. The labyrinth today is an exact copy, made in the 19th century.[34]

The labyrinth on the floor of the nave

The labyrinth on the floor of the nave The centre of the labyrinth

The centre of the labyrinth

The chevet and east chapels

The east end of the cathedral largely preserves the original medieval design, containing the choir, the space reserved for the clergy. It is surrounded by a very ornate carved wooden screen, and seven chapels in the semicircular apse. An ambulatory allows visitors to walk around the circuit of the chapels behind the choir.[31]

The semicircular wall at the east end marked a new stage in the development of the Gothic. The upper walls of the clerestory, just beneath the vaults, and the walls of the triforium below them were entirely filled with glass. The arches of the triforium and arcades were topped with pointed arches, stressing the vertical, and admitted a maximum amount of light from different heights and directions, depending upon the time of day. Light also filtered down into the disambulatory from the upper levels.[31]

Seven chapels are arranged around the semicircular east end. The Lady's Chapel, dedicated to The Virgin Mary, was at the very end of the cathedral, was reserved for the servants of the Canons who lived in the cloisters of the cathedral. The first chapel on the south side of the chevet is devoted to Saint Eloi, and now serves as the entrance to the cathedral treasury. Its primary decoration is a series of eight paintings of the Sibyls from the 16th century.

Three of the chapels in the east end were entirely re-fitted by Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century to return them to what was thought to be their medieval aspect; these are St. Theodisius, in the north, The Lady's Chapel (Notre-Dame-Drapiere) in the centre, and Saint Jacques or the Sacred Heart, in the south. Viollet-le-Duc designed all the furnishings and decoration, including the gilded bronze altar in the Chapel of the Sacred Heart.[26]

The chevet or east end of the cathedral, with its radiating chapels

The chevet or east end of the cathedral, with its radiating chapels Chapel of St. Eloi, painting of a Sibyl (16th century)

Chapel of St. Eloi, painting of a Sibyl (16th century) Chapel of Notre Dame-Drapiere (Lady's Chapel), early 14th century with 19th century furnishings and decoration

Chapel of Notre Dame-Drapiere (Lady's Chapel), early 14th century with 19th century furnishings and decoration

The lateral and transept chapels

In addition to the chapels at the east end, small chapels occupy both sides of the nave and angles of the transept. The original decoration of these chapels was replaced in the 18th century by the present decor. Each chapel is dedicated to a particular saint, and features large paintings reaching up to the windows, altars, stone and wooden statuary, all from the 18th century. The chapels are closed by ornamental wrought-iron screens and gates.[35]

In the north transept, the Chapel of Saint Peter occupies the northeast corner. It was created in response to the plague epidemic that struck Amiens in 1667–68, but was not completed until 1709. It was made by Gilles Oppenord, one of the pioneers of the Rococo style.

On the east side of the north transept is the Chapel of Saint Sebastian, also known as the Chapel of the Green Pillar. At its summit is a sculpture by Nicolas Blasset, "Saint Sebastian surrounded by the allegories of Justice, Peace, and Saint Roche", which was completed in 1627. A sculpture of Saint Louis by Louis Duthoit was added to the chapel in 1832.[35]

On the west wall of the north transept are four scenes in high relief showing Christ driving the merchants from the Temple, made in 1523 by Jean Wytz.

Another early work in the transept is the altarpiece of the Chapel of Our Lady of the Red Pillar, an assembly of sculpture and paintings, clustered around a main pillar. It was completed in 1627 by Nicolas Blasset. The painting of the Assumption of Mary (1627) is by François Franken, and the sculptures of Saint Sebastian, the Virgin Mary, David and Solomon, and Judith and Saint Genevieve, made by Blasset.[35]

The south transept contains the Chapel of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, in the southeast corner, with statues of those saints made by Jean-Baptiste Michel Dupuis in 1749. It also contains an altarpiece with a painting of the Adoration of the Magi from the early 18th century.

A group of polychrome reliefs illustrating the vow of John the Baptist, made in 1511, is found on the west wall of the south transept.[35]

.jpg.webp) The Altar of the Chapel of the Red Pillar (1627)

The Altar of the Chapel of the Red Pillar (1627) Saint Sebastian, by Nicolas Blasset in the Chapel of the Green Pillar

Saint Sebastian, by Nicolas Blasset in the Chapel of the Green Pillar Altar of the Chapel of the Green Pillar (17th c.)

Altar of the Chapel of the Green Pillar (17th c.)

The treasury

The treasury is located in the apse at the east end of the cathedral, on the southern side near the sacristy. The collection of reliquaries and other precious objects was dispersed in 1793 during the Revolution, but gradually some of the treasures were returned, some were recreated, while others were added by other donors.

Objects of particular interest include the Crown of Paraclet, made in about 1230–1240, which was saved from destruction at the Cistercian monastery of Paraclet, not from Amiens. It contains what are said to be relics of the Passion of Christ, set into a gilded and enamelled crown decorated with jewels, pearls and precious stones. A fine statue of the Virgin Mary and Child, made of polychrome wood in the 15th century is also found in the treasury.[36]

Other objects of interest are found in the chapels along the nave and transept. The initial impetus for the building of the cathedral came from the installation of the reputed head of John the Baptist on 17 December 1206. The head was part of the loot of the Fourth Crusade, which had been diverted from campaigning against the Turks to the sacking of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. A sumptuous reliquary, with the face of the Saint, was made to house the skull. Although the skull and original reliquary were lost during the Revolution, a 19th-century replica was made and is displayed on the north aisle.

The crown reliquary of Paraclet (1230–1240)

The crown reliquary of Paraclet (1230–1240) Virgin and Child, polychrome wood (15th c.)

Virgin and Child, polychrome wood (15th c.) Copy of the reliquary made for the head of Saint John the Baptist (19th century)

Copy of the reliquary made for the head of Saint John the Baptist (19th century)

Stained glass windows

Only a few of the original stained glass windows still remain; many were removed during the remodeling of the cathedral in the 18th century. Others were destroyed when the church was sacked by the Protestant Huguenots in 1561, by hurricanes in 1627 and 1705; by the explosion of a powder mill in 1675. A large group of early windows, which had been removed in 1914 to protect them from damage during the First World War, were destroyed in 1920 when the studio where they were stored was destroyed by fire.[37]

Some of the early glass dates from same period as those of Chartres Cathedral, though most of the earliest windows have disappeared. Some of the earliest glass, from about 1269, is found in two of the lancets in the high windows of the chapel at the end of the apse, at the east end of the cathedral. These two windows depict the same scene, one the inverse of the other. They show a clergyman presenting the stained glass to the Virgin Mary, to whom the chapel is dedicated. Angels carry crowns which they hold over the heads of the elongated figures.[37]

Several very early panels of glass, from about 1300, can be seen in the windows of the triforium, the mid-level of the wall, in the apse. They depict a procession of saints, apostles, prophets and bishops of monumental size, set against a background of light-coloured glass, to make them stand out. They face the centre of the Apse, underneath a window depicting the Virgin Mary and the Annunciation.

A few other original 13th century panels, including one representing King David from a Tree of Jesse window depicting the genealogy of Christ, are found in the Chapel of Saint Francis of Assisi, in the apse.[37]

The innovative feature of the upper windows of Amiens Cathedral was how they filled the entire space of the upper wall. Thanks to the thin stone mullions that separate the group of lancet windows and the small circular windows on the upper levels, and the massive buttresses on the exterior that provided support for the walls, the individual windows in each bay seemed to merge into one great window, filling the nave below with light.[38]

The largest part of the stained glass in the cathedral comes from the 19th century. The window in the Chapel of Saint Theodosius in the apse, for example, was made by the glass artist Gérente in 1854 donated by Emperor Louis Napoleon. The lower portions of the window depict the Emperor, the Empress Eugenie, the Bishop of Amiens and Pope Pius IX. The cathedral also features some 20th-century Art Deco glass, in the Chapel of Sacré Coeur, made in 1932–1934 by the master glass artist Jean Gaudin, based on designs of the painter Jacques le Breton.[39]

Stained glass windows in the ambulatory

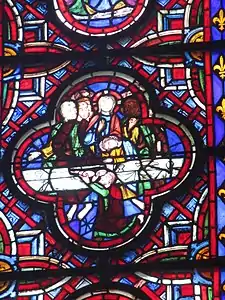

Stained glass windows in the ambulatory Medallion of the Last Supper (13th century)

Medallion of the Last Supper (13th century) Windows of the central apse chapel (13th century)

Windows of the central apse chapel (13th century) Four windows from the 13th century

Four windows from the 13th century Windows of the Chapel of Saint-Etienne

Windows of the Chapel of Saint-Etienne Art Deco stained glass by Jean Gaudin (1933)

Art Deco stained glass by Jean Gaudin (1933)

Rose windows

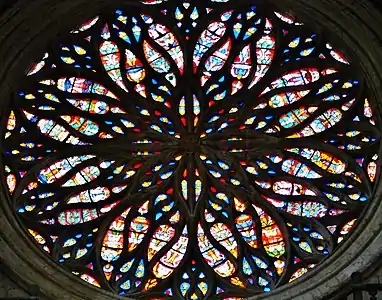

The three rose windows each represent a different period of the cathedral's construction. The rose window on the west facade is the oldest, from 1221 to 1230, from the High Gothic period, and represents Jesus Christ surrounded by the symbolic figures of the Apocalypse. The rose window of the north transept has the characteristic radiating tracery of the Rayonnant Gothic.[40]

The rose window of the south transept is the latest, from 1489 to 1490, with the curves and reverse curves of the late Gothic Flamboyant style. It depicts fourteen angels, heads towards the centre of the window, in a style characteristic of the Picard style of window in the 15th century.[41]

High Gothic rose window of the west facade (1221–1230)

High Gothic rose window of the west facade (1221–1230) Rayonnant rose window of the north transept (14th c.)

Rayonnant rose window of the north transept (14th c.) Flamboyant rose window of the south transept (16th c.)

Flamboyant rose window of the south transept (16th c.)

The organ

The first organ in the cathedral was a gift from Alphonse Lemire, an official of the court of King Charles VI of France. It was installed on the interior of the west wall of the cathedral, below the rose window, between 1442 and 1449. All that survives of this organ is wooden gallery, lavishly decorated with Flamboyant Gothic carvings. The current pipes and case were installed in 1549, with additions in 1620. It was restored in the 19th century and again shortly before World War II.[42]

The Cathedral organ

The Cathedral organ The Flamboyant decoration of the organ (15th century)

The Flamboyant decoration of the organ (15th century)

Light show – the West Front in colour

During the process of laser cleaning in the 1990s, evidence was discovered of the original multi-coloured painted decoration of the west front. A technique was perfected to determine the exact composition of the paints used in the 13th century. In conjunction with the laboratories of EDF and the expertise of the Society Skertzo, lighting techniques were developed to project these colours directly on the façade with precision, recreating the polychromatic appearance of the 13th century without touching the surface of the stone. When projected on the statues around the portals, the result is a stunning display that brings the figures to life. The projected colors are difficult to photograph, but a good quality DSLR camera can provide excellent results, as shown below.

The full effect of the colour may be best appreciated by in-person viewing, with musical accompaniment, which can be done at the Son et lumière shows which are held on Summer evenings, during the Christmas Fair, and over the New Year.[43][44]

Sound and light show – central portal

Sound and light show – central portal Portal illuminated to suggest original colours

Portal illuminated to suggest original colours Sound and light show – central portal

Sound and light show – central portal

Notable burials and memorials

- Elisabeth, Countess of Vermandois, wife of Philip I, Count of Flanders

- Charles de Hémard de Denonville, Catholic bishop and cardinal

- Antoine de Créqui Canaples (heart only), Catholic bishop and cardinal

Memorials

- The cathedral's south door contains eleven memorial tablets to commemorate the war dead from World War I, mainly those who fought in the Battle of the Somme (1916). Nations commemorated are mostly British Empire and dominions (modern-day countries of the Republic of Ireland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand).

- Notable individuals commemorated include French World War I general Marie-Eugène Debeney, British Army officer Raymond Asquith, and French World War II general Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque.

See also

- High Gothic

- Rayonnant

- Gothic Architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic cathedrals in Europe

Notes and citations

- Mérimée database 1992

- "Chronologie". Monumentshistoriques.free.fr. 18 April 1928. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Bishop Jean-Luc Marie Maurice Louis Bouilleret". Catholic-Hierarchy.com. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Kremlin and Red Square, Moscow". UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Watkin 1986, p. 134.

- Mignon 2015, p. 28.

- Lours 2018, p. 41.

- "Amiens Cathedral". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Eudcational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 7.

- Sachy 1770.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 9.

- Lours 2018, p. 42.

- NOVA | Building the Great Cathedrals Archived 3 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 10.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 12.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 93.

- Rivallain, Gael (12 December 2019). "Stephen Murray: "Quand on rentre dans la cathédrale d'Amiens, c'est comme si vous vous mettiez à respirer profondément"". Courrier picard (in French). Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Murray to Give 70th University Lecture". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Stephen Murray receives Honorary Doctorate from the University of Picardy, Jules Verne – Department of Art History and Archaeology – Columbia University". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 92.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 23.

- footnotes Archived 27 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Duvanel 1998, p. 12.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 16.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 32-33.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 79.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica online, "Flying Buttress – Architecture"

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 43.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 13.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 47.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 62.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 56.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 76.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 45.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 72.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 85.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 81–82.

- Brisac 1994, p. 33.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 82.

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 81.

- . Site of Les Amis de la Cathédrale d'Amiens – Les Vitraux

- Plagnieux 2003, p. 80.

- "Gothic art in Picardy". Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- Official site of the polychromatic façade of the cathedral Archived 29 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography and sources

- Brisac, Catherine (1994). Le Vitrail (in French). Paris: La Martinière. ISBN 2-73-242117-0.

- Duvanel, Maurice (1998). La Cathédrale Notre-Dame d'Amiens (in French). Éditions Poire-Choquet. ISBN 2-9502147-5-4.

- Lours, Mathieu (2018). Dictionnaire des Cathédrales (in French). Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-27558-0765-3.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Plagnieux, Philippe (2003). Cathérale Notre Dame d'Amiens (in French). Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN 978-27577-0404-2.

- Sachy, Jean-Baptiste Maurice de (1770). Histoire des évesques d'Amiens (in French). Abbeville: Veuve de Vérité Libraire.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- "Amiens Cathedral". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- Cothren, Michael A.; Prache, Anne (1996). "Amiens". In Turner, Jane (ed.). Dictionary of Art. Vol. 1. London: Macmillan. pp. 777–781.

- "Amiens Cathedral". World Heritage Site. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007.

- "Amiens Cathedral, under Renovation." (undated albumen print from c. 1865–1895), A. D. White Architectural Photographs Collection, Cornell University Rare and Manuscript Collections (5/5/3090.01261)

- "Monument historique – PA00086250". Mérimée database of Monuments Historiques (in French). France: Ministère de la Culture. 1992. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

Further reading

- Dusevel, Hyacinthe (1839). Notice historique et descriptive sur l'église cathédrale d'Amiens (Second ed.). Amiens: Caron, Vitet.

- Murray, Stephen (1996). Notre Dame, Cathedral of Amiens: The Power of Change in Gothic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49735-0.

- Murray, Stephen (2021). Notre-Dame of Amiens: Life of the Gothic Cathedral. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231195768.

External links

- Towers of Amiens Cathedral - Official Website (in French and English)

- Amiens Cathedral images, 360° panoramas, and essays. In "Mapping Gothic France," a database created by Columbia University and Vassar College.

- 360° photos of the cathedral

- Outstanding photos of the cathedral

- Photos

- The Portals, Access to Redemption by Professor Stephen Murray)

- Photos of the magnificent reproduction of the cathedral colors by laser projection

- "Background, Structural and Statistical Information for the cathedral". Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Youtube page of Amiens Videos produced by the Media Center for Art History at Columbia University for the Core Curriculum class "Masterpieces of Western Art"

- Photos of the Amiens Cathedral (polish)

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Amiens Cathedral | Art Atlas