Châteauneuf-du-Pape

Châteauneuf-du-Pape (French pronunciation: [ʃatonœf dy pap]; Provençal: Castèu-Nòu-De-Papo) is a commune in the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in Southeastern France. The village lies about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the east of the Rhône and 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) north of the town of Avignon. As of 2019 the commune had a population of 2,055.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape | |

|---|---|

A view of the village from the southeast | |

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

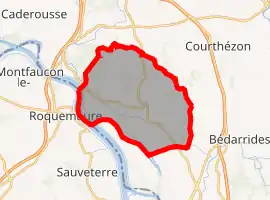

Location of Châteauneuf-du-Pape  | |

Châteauneuf-du-Pape  Châteauneuf-du-Pape | |

| Coordinates: 44°03′25″N 4°49′55″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Vaucluse |

| Arrondissement | Carpentras |

| Canton | Sorgues |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Claude Avril[1] |

| Area 1 | 25.85 km2 (9.98 sq mi) |

| Population | 2,055 |

| • Density | 79/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 84037 /84230 |

| Elevation | 20–130 m (66–427 ft) (avg. 117 m or 384 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

A ruined medieval castle sits above the village and dominates the landscape to the south. It was built in the 14th century for Pope John XXII, the second of the popes to reside in Avignon. None of the subsequent Avignon popes stayed in Châteauneuf but after the schism of 1378 the antipope Clement VII sought the security of the castle. With the departure of the popes the castle passed to the archbishop of Avignon, but it was too large and too expensive to maintain and was used as a source of stone for building work in the village. At the time of the Revolution the buildings were sold off and only the donjon was preserved. During the Second World War an attempt was made to demolish the donjon with dynamite by German soldiers but only the northern half was destroyed; the southern half remained intact.

Almost all the cultivable land is planted with grapevines. The commune is famous for the production of red wine classified as Châteauneuf-du-Pape Appellation d'origine contrôlée which is produced from grapes grown in the commune of Châteauneuf-du-Pape and in portions of four adjoining communes.

Toponym

The first mention of the village is in a Latin document from 1094 that uses the name Castro Novo. The term castrum or castro in the 11th century was used to denote a fortified village, rather than a castle (castellum). The current French name of "Châteauneuf" (English: "New Castle") is derived from this early Latin name and not from the ruined 14th-century castle that towers above the village. Just over a century later in 1213 the village was referred to as Castronovum Calcernarium. Other early documents use Castronovo Caussornerio or Castrum Novum Casanerii. The official French name became Châteauneuf Calcernier. The word 'Calcernier' comes from the presence of important lime kilns in the village. Calcernarium is derived from the Latin calx for lime and cernere means sift or sieve. From the 16th century the village was often referred to as "Châteauneuf du Pape" or "Châteauneuf Calcernier dit de Pape", because of the connection with Pope John XXII, but it was not until 1893 that the official name was changed from "Châteauneuf Calcernier" to "Châteauneuf-du-Pape".[3][4] The name in the Provençal dialect of the Occitan language that was spoken in the village is Castèu-Nòu-De-Papo.[5]

History

Early settlement

The earliest settlement is believed to have been near the Chapel Saint-Théodoric, to the east of the current village center. This Romanesque chapel was erected by the monks of the abbey of Saint-Théodoric in Avignon at the end of the 10th or the beginning of the 11th century and is the oldest building in the commune.[6] Although the village lay within the Comtat Venaissin, it was one of the fiefs of the bishop of Avignon and thus had a special status. The bishop of Avignon also held the fiefs of Gigognan and Bédarrides.[7]

In the second half of the 11th century a fortified village was built higher up the hill by the Viscount Rostaing Béranger in the fiefdom of his brother, the bishop of Avignon. The wall of the present church building formed part of the fortification and the arrowslits in the clock tower are still visible. Two towers and other vestiges of these early fortifications have survived.[8] The new village would have contained a suitable fortified residence for the bishop which is believed to have been located between the church and the site of the later castle.[9]

In 1238 the bishop of Avignon obtained an important privilege from the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1195–1250). Salt that was shipped on the Rhône and landed at Châteauneuf would not be subject to tax. As a result, the trade in salt became a considerable source of revenue for the village.[10]

Avignon popes

Bertrand de Got, archbishop of Bordeaux, was elected pope in 1305, and took the name of Clement V. He transferred the papacy to Avignon in 1309. The register of pontifical letters reveals that Clement V visited Châteauneuf on several occasions, sometimes for long periods.[11] While in the village he would have been a guest at the bishop's residence.[12] In 1312 he stayed in the village from 6–22 November. In 1313 he returned from 9 May to 1 July and again from 19 October to 4 December. The following year, 1314, he was in Châteauneuf from 24–30 March. He died in the castle of Roquemaure on the opposite bank of the Rhône on 7 April 1314.[11]

The next pope, Jacques Duèze, was elected in 1316 and took the name John XXII. After his coronation in Lyon on 5 September 1316, he travelled down the Rhône and spent 10 days in Châteauneuf before he arrived in Avignon. He had served as the bishop of Avignon between 1310 and 1313 and while bishop had also been the seigneur of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. He had arranged for his nephew Jacques de Via to succeed him as bishop. But on the death of his nephew in 1317 he chose not to appoint a successor, so during his papacy the village belonged directly to the pope. John XXII initiated a large number of building projects, including additions to the Palais des Papes in Avignon as well as defensive castles at Barbentane, Bédarrides, Noves and Sorgues. In 1317, work began on the construction of the castle in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. John XXII derived little benefit from the new castle, which was not completed until 1333, a year before his death. The ruins of the castle are now a prominent feature of the village.[13]

There is no record of the next Avignon pope, Benedict XII (1334–1342) having ever stayed in this castle, but in 1335 he granted the village the right to have a ship mill on the Rhône, a market every Tuesday and two fairs during the year. He did not keep the post of bishop of Avignon and appointed a new bishop to replace himself in 1336.[14] None of the following four popes stayed in Châteauneuf-du-Pape either, but after the schism of the Catholic Church in 1378, the Avignon antipope Clement VII frequently sought the security of the castle and from 1385 to 1387 had improvements carried out on the building.[15]

In the 14th century the presence of the pope in Avignon and construction of the castle brought considerable prosperity to the village. The economy was based on agriculture, but the villagers also possessed lime kilns and the local merchants supplied roof tiles for the Palais des Papes in Avignon and floor tiles for the castle being built in Barbentane.[16] The village outgrew the mid-11th century defensive walls and houses began to be built outside. In 1381 the village obtained permission to impose a local tax to fund the construction of a new system of fortifications around the village. These defensive towers have all disappeared except for the Portalet tower in the Rue des Papes, but parts of the walls remain.[17]

Pope John XXII's castle

Construction

In 1317, one year after his election, Pope John XXII ordered the construction of a castle at the top of the hill above the village.[18][19] Some of the stone may have been from a local quarry but most was probably imported from Courthézon. The mortar and the roof tiles would have been manufactured in the village. To provide water, between August 1318 and July 1319, a large deep well was dug in the courtyard to the northeast of the donjon.[20] According to the papal accounts, much of the work was completed by 1322, but in 1332 there is an entry for the purchase of timber from Liguria for four towers.[20][21] The castle not only had a defensive role, but was also designed to serve as a summer residence. There was a garden on the west side and a 10 hectare park to the north enclosed by high walls in which vines, olive trees and fruit trees were cultivated.[20]

Neglect

With the departure of the popes the castle became part of the fief of the bishop and, after 1475, the archbishop of Avignon, but it was much too big and expensive for them to maintain.[22][lower-alpha 1] The captain in charge of the village's defences lived in the castle but there was no permanent garrison, and most of the buildings were allowed to deteriorate. In the 16th century Huguenots occupied Châteauneuf for several months during the Wars of Religion. In March 1563, they pillaged the village and set fire to the church and parts of the castle including the apartments of the pope. The extent of the damage is not known.[24]

During the 17th century, and perhaps earlier, the ruined buildings of the castle were used as a source of stone for the construction of houses in the village. The community also used the stone to repair the walls around the village (18 to 20 cartloads in 1717) and to repair the church in 1781.[25] At the time of the Revolution the castle had not been inhabited for a number of years. The buildings and the adjoining parkland were put up for sale and bought in July 1797 by Jean-Baptiste Establet, a farmer in the village. The following year, these were resold in 33 equal parts. By 1848 most of the castle had been destroyed by the purchasers.[26] The mayor forbade the destruction of the donjon and in May 1892 the castle was listed as one of the French Historical Monuments.[26][27] During the Second World War, the donjon was used as an observation post by German soldiers. In August 1944, just before their departure, they attempted to demolish the building with dynamite but by chance, only the northern half of the tower was destroyed, leaving the southern half as it appears today.[28] In the 1960s the municipality constructed a meeting hall within the ancient ruined cellar of the castle.[28]

Buildings

There are no surviving plans of the castle from the 14th century. The earliest depiction is an anonymous drawing from the Album Laincel in the collection of the Musée Calvet in Avignon that dates from the second half of the 17th century. By this time the castle had not been properly maintained for three centuries and the drawing is probably an interpretation by the artist of the surviving structure. Another source of information is a plan of the village from the 1813 cadastre which indicates the position of some of the buildings but not their original function.[29] The appearance of the donjon before its destruction in 1944 is known from old photographs.[30][31]

The main entrance to the castle was just above the village and consisted of two successive gatehouses. The first was on the path up from the church and the second was just to the east of the donjon. The vulnerable north side of the castle would have been protected by a deep ditch. The northern entrance was defended by a tower and was probably accessed by a drawbridge. Very little is known about the buildings of the castle other than the ruined donjon and papal apartments. The castle contained a chapel dedicated to Saint Catherine but the location is uncertain.[29] The donjon had a ground floor with a low barrel vaulted ceiling and two upper levels with rib vaulted ceilings. The large roof terrace was surrounded by a machicolated battlement. The floors were connected by a stone staircase built into the thickness of the western wall.[32] The entrance to the tower on the east side was protected by an unusually tall bretèche. A similar bretèche survives above the entrance to the Tour Philippe-le-Bel in Villeneuve-lès-Avignon.[33]

The two large ruined walls to the west of the donjon formed part of a rectangular building reserved for the pope and his close associates. The large ground-floor room was 26 m in length, 9 m in width and 5.5 m in height. The ceiling was supported by wooden beams with three central columns. The floor was paved with large stone slabs. This room, together with a smaller room to the north, were probably used for storage. On the first floor was the great hall of the castle in which banquets would have been held. It had the same dimensions as the ground floor storeroom but with a higher ceiling (6.5 m). It was lit by four large rectangular windows providing views over the Rhône valley. There were also three smaller windows to increase the ventilation, two facing west and one facing south. The walls were decorated with frescoes and a band of large red, bistre and black roses. A door at the north end of the hall opened into a well-lit smaller room with a chimney. The main entrance to the hall was on the east side near the donjon and close to the modern steps. The top floor of the building was lit by three large windows provided with benches and three smaller rectangular windows. The irregular pattern of the windows suggests that there were several rooms, perhaps apartments for the pope. The tiled roof with two equal slopes was entirely protected by the large outer walls.[34]

Tiles

An archaeological excavation carried out in 1960 in the basement of the ruined rectangular building recovered a number of small glazed terracotta floor tiles. They date from the first half of the 14th century and would have originally decorated the main hall on the first floor. The tiles are square, 125–130 mm on a side and 20 mm in thickness. They are decorated in a Hispano-Moresque style which is more usually associated with dishes and jugs. Many have a plain coloured glaze, either green, yellow or occasionally black but some have designs in brown or green on a white tin glazed background.[35][36] The tiles are similar to those discovered in 1963 on the floor of Pope Benedict XII's studium in the Palais des Papes. The room was built between 1334 and 1342 and is therefore a little later. The Châteuneuf tiles are slightly larger and often have animal designs. They were almost certainly manufactured in Saint-Quentin-la-Poterie. The papal accounts record large purchases of tiles in 1317.[37][38][lower-alpha 2]

In 1994, a small archaeological excavation was carried out on the terrace at the foot of the southern façade of the papal quarters. Altogether fifty tiles were recovered that had been scattered in the modern landfill. At the same time, a survey was conducted in the village to locate tiles held in private collections. A hundred more tiles were identified that had been collected by local people in the 19th and 20th centuries. These new finds enlarged the established iconography and provided more precise information on how the tiles were made.[40]

Parish church

The parish church is now called "Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption" but over the centuries it has been "Notre-Dame" (1321), "Saint-Théodoric" (1504), "Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie et Saint-Théodoric" (1601), "Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie-del'Assomption" (1626) and "Saint-Théodoric" (1707).[41]

The church probably dates from the end of the 11th century when the village was first fortified. It certainly existed in 1155 when a papal bull issued by Adrian IV confirmed that bishop of Avignon possessed "Châteauneuf Calcernier with its churches". Almost nothing survives of the original Romanesque church. It was rectangular in plan with the entrance at the western end. The square tower at the southeast corner which now serves as the bell tower was not part of the early church but formed part of the fortifications of the village. It later housed the municipal archives and in the 16th century supported a clock. The round tower at the northeast corner of the church was also part of the village fortifications but later served as a bell tower. In 1321 Pope John XXII paid for the construction of a side chapel, dedicated to Saint Martin, on the south side of the nave abutting the square tower.[42][43] A second chapel, dedicated to Saint Anne, was constructed in the 16th century near the Saint Martin chapel.[44]

At the end of the 18th century the church was in a bad state of repair and had become too small for the village. Beginning in 1783 the church was extended towards the west and the entrance moved to the south wall. New windows were also created in the south wall of the nave.[45]

In 1835 the square tower was converted into the existing bell tower. In the 19th century, before the arrival of phylloxera, the village was very prosperous. Between 1853 and 1859 it paid for a major enlargement of the church in which side aisles were created either side of the nave. The chapels of Saint-Anne and Saint-Martin were demolished to create the southern aisle. To build the northern aisle, the commune bought land and a house on the other side of the Rue Ancienne Ville and displaced the street to the north.[46]

In 1981 the church was restored and the plaster on the interior walls was removed.[46]

Château de Lhers

The ruined castle of Lhers[lower-alpha 3] sits on a limestone outcrop, 3.2 km (2.0 mi) west of the village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape on the left bank of the Rhône.[lower-alpha 4] Up to the 18th century there was a village of Lhers associated with this castle. It is mentioned (as Leris) for the first time in a document dated 913 in which Louis the Blind, Count of Provence, gave the castle, one (or two) churches, a port on the Rhône and the land of the parish, to Fouquier,[lower-alpha 5] the bishop of Avignon. In 916, Bishop Fouquier gave the churches, the port and the parish to the churches of Notre-Dame and Saint-Étienne in Avignon. Neither the castle nor the income from the tolls collected from boats using the Rhône are mentioned in this document.[48]

The plan of the castle is approximately square (25 m x 23 m), with a round tower at the southeast corner and a square tower at the northwest corner. The north side of the outcrop drops away vertically so there was no need for a defensive wall. A deep well is in the northeast corner. A drawing by the Jesuit architect Étienne Martellange shows the appearance of the castle in 1616.[49] The architecture of the square tower suggests that it was built after the end of the 12th century.[50] Only the ground floor survives. The round tower is later and was probably built in the 14th century.[51] The surviving ruins therefore do not date from the 10th century when the castle is first mentioned in written records. The limestone blocks of the earlier castle were no doubt reused to construct the actual castle.[52]

The Rhône was liable to violent floods and the river would change position or bifurcate, creating and destroying islands. The number and the position of the islands varied over the centuries which led to a series of boundary disputes between the communities of Lhers and Châteauneuf.[41] In the Cassini map of France, dating from the last third of the 18th century, the castle is shown sitting on an island.[53] At the time of the Revolution, the fief of Lhers included land joined to the right bank near Roquemaure, an island near the left bank separated by a small branch of the river, another island in the middle of the Rhône on which sat the castle, several gravel banks and a farm on land that was contiguous with Châteauneuf. The land of the fief was initially considered to be part of the commune of Roquemaure, but in 1820 the castle and the land were transferred to the commune of Châteauneuf-du-Pape.[41] In 1992 the castle was listed as one of the French historical monuments. It is privately owned.[54]

Almost nothing survives of the two churches mentioned in the early documents. The church of Sainte-Marie was destroyed during the Revolution. The ruins were visible until the canalization of the Rhône in the 1970s. The other church, dedicated to the Saints Cosmas and Damian, was probably the earlier of the two. It is mentioned in a papal bull issued in 1138 by Pope Adrian IV that confirmed that the bishop of Avignon possessed the fief of Lhers. The church is mentioned again in another document from 1560.[55]

Wine

Although viticulture must have existed in the village well before the arrival of the popes, nothing is known about it. The Introitus et Exitus, the financial record of the Papal Treasury, shows regular purchases of small quantities of wine from the village.[56][57] At the time, wine was difficult to transport and difficult to conserve so most was drunk locally when less than a year old.[58] Wine production expanded in the 18th century with the rapid development of the wine trade. From the correspondence of the Tulle family who owned the vineyards of the La Nerthe estate, we learn that the 40 hectolitres of wine produced was exported to England, Italy, Germany and all over France. In 1923, the local wine producers led by the lawyer Pierre Le Roy de Boiseaumarié began a campaign to establish legal protection for the wine from the commune.[59] The delimited area and the method of wine production were awarded legal recognition in 1933. Small changes to the initial regulations were made in 1936 and 1966.[60]

The wine classified as Châteauneuf-du-Pape Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) is produced from grapes grown in the commune of Châteauneuf-du-Pape and portions of the four adjoining communes in the Vaucluse. The vineyards cover an area of approximately 3,200 hectares. Of this total 1,659 hectares (52%) lie within the commune of Châteauneuf, 674 hectares (21.1%) within Courthézon, 391 hectares (12.3%) within Orange, 335 hectares (10.5%) within Bédarrides and remaining 129 hectares (4%) in Sorgues.[60] Unlike its northern Rhône neighbours, Châteauneuf-du-Pape AOC permits thirteen different varieties of grape in red wine but the blend must be predominantly grenache. In 2010 there were 320 producers. The total annual production is around 100,000 hectolitres (equivalent to 13 million bottles of 0.75 litre) of which 95% is red. The remainder is white: the production of rosé is not permitted under this AOC.[59]

Population

The earliest figure for the population of the village is from the census of 1344, which recorded 508 dwellings or "hearths". As there were typically 4.5 inhabitants per dwelling, this represented around 2,000 inhabitants, a very large village for the time. The figure was not surpassed until the 20th century. After 1344 there are no further records until 1500, when the population was 1,600. In the 17th century there were several epidemics of bubonic plague and by 1694 the population had dropped to 558. During the 18th century the population of the village doubled, reaching 1,471 in 1866, but when the phylloxera devastated the vineyards the population dropped by a quarter to 1,095 in 1891.[61][4] The population was 2,179 in 2012.[62]

Climate

Châteauneuf-du-Pape has a humid subtropical climate Cfa in the Köppen climate classification, with moderate rainfall year-round. July and August are the hottest months with average daily maximum temperatures of around 30 °C (86 °F). The driest month is July when the average monthly rainfall is 37 millimeters, just a little too wet for the climate to be classified as Mediterranean (Köppen Csa).[63] The village is often subject to a strong wind, the mistral, that blows from the north.

| Climate data for Orange-Caritat (9 km (6 mi) north of the village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

27.1 (80.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.1 (86.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52.7 (2.07) |

39.1 (1.54) |

43.2 (1.70) |

65.8 (2.59) |

65.4 (2.57) |

37.9 (1.49) |

36.6 (1.44) |

39.0 (1.54) |

97.3 (3.83) |

92.7 (3.65) |

75.4 (2.97) |

55.8 (2.20) |

700.9 (27.59) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.0 | 137.1 | 192.5 | 230.4 | 264.6 | 298.9 | 345.3 | 310.7 | 237.6 | 187.1 | 135.2 | 123.8 | 2,595.2 |

| Source: infoclimat.fr[64] | |||||||||||||

Schools

There are two state schools in the commune. The nursery school, École maternelle Jean Macé, is attended by around 87 children between the ages of three and six.[65] The primary school, École primaire Albert Camus, is attended by 137 children between the ages of six and eleven.[66][67] After the age of eleven most children attend the Collège Saint Exupéry in Bédarrides.[68]

Notes

- In 1475 Pope Sixtus IV upgraded the bishopric into an archbishopric.[23]

- The entry for 21 September 1317 records the purchase of 12,000 floor tiles from Saint-Quentin-la-Poterie that were of divers colours and painted with figures. (de s. Quintino pro 12000 tegulorum ad pavimentandum depictorum cum figuris et diversorum colorum).[39]

- The name of the castle has been written in different ways. Latin documents use Leris and Lertio whereas French documents use L'airs, Lair, L'ers, l'Hers and Lhers.[47]

- The coordinates of the Château de Lhers are 44°3′14.9″N 4°47′29.9″E.

- The name of the bishop (Fulcherius in Latin) is also written as Foulques.[47]

References

- "Répertoire national des élus: les maires" (in French). data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises. 13 September 2022.

- "Populations légales 2019". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 29 December 2021.

- Portes 1993, pp. 15, 21–23.

- Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Châteauneuf-du-Pape, EHESS. (in French)

- Mistral 1879, p. 492.

- Portes 1993, pp. 17, 285–286.

- Portes 1993, p. 21.

- Portes 1993, p. 251.

- Portes 1993, p. 253.

- Portes 1993, pp. 26–27.

- Portes 1993, p. 27.

- Portes 1993, p. 293.

- Portes 1993, pp. 28–29.

- Portes 1993, pp. 29–30.

- Portes 1993, p. 30.

- Portes 1993, pp. 31–34.

- Portes 1993, pp. 265–269.

- Portes 1993, pp. 253–254.

- Schäfer 1911, pp. 274, 276.

- Portes 1993, p. 254.

- Schäfer 1911, p. 311.

- Portes 1993, p. 259.

- Portes 1993, p. 42.

- Portes 1993, pp. 42–43, 259.

- Portes 1993, p. 363.

- Portes 1993, p. 263.

- Base Mérimée: Château, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Portes 1993, p. 265.

- Portes 1993, p. 255.

- Portes 1993, p. 260.

- Le Boyer, Noël (photographer). "2633 Châteauneuf du Pape". Ministère de la culture et de la communication. The image has been flipped horizontally.

- Portes 1993, pp. 255–256.

- Maigret 2002, p. 13.

- Portes 1993, pp. 257–259.

- Portes 1993, p. 257.

- Gagnière & Granier 1973–1974, pp. 34–37.

- Gagnière & Granier 1973–1974, pp. 56–60.

- Schäfer 1911, pp. 280, 281.

- Schäfer 1911, p. 280.

- Carru, Dominique (29 April 2010). "Petits carrés d'histoire XIVe siècle: Nouvelles collectes à Châteauneuf-du-Pape" (in French). Domain de Beaurenard. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- Portes 1993, p. 277.

- Portes 1993, pp. 277–279.

- Schäfer 1911, pp. 739, 810, 813.

- Portes 1993, p. 279.

- Portes 1993, pp. 279–281.

- Portes 1993, pp. 281–283.

- Portes 1993, p. 269.

- Portes 1993, pp. 269–271.

- Portes 1993, p. 271.

- Perrot & Garnier 1972, p. 73.

- Perrot & Garnier 1972, p. 74.

- Portes 1993, pp. 269–277.

- "France 1750, Cassini map". David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Retrieved 9 February 2021..

- Base Mérimée: Château de l'Hers ou de l'Airs (ruines), Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Portes 1993, pp. 271–272.

- Portes 1993, p. 235.

- Schäfer 1914, pp. 711, 766, 796.

- Portes 1993, pp. 235–236.

- "Cahier des charges de l'appellation d'origine contrôlée " CHÂTEAUNEUF-DU-PAPE " homologué par le décret n°2011-1567 du 16 novembre 2011, JORF du 19 novembre 2011" (PDF). République Française: Ministère de l'agriculture, de l'agroalementaire et de la fôret. 2011. pp. 362–372 (pages unnumbered). Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- Portes 1993, p. 243.

- Portes 1993, pp. 195–196.

- "Commune de Châteauneuf-du-Pape (84037) – Dossier complet" (in French). Institut national de la statistique et des études economique. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- "Normales et records pour la période 1981–2010 à Orange-Caritat". infoclimat. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- "École maternelle publique Jean Macé". Ministère de l'éducation nationale. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "École primaire publique Albert Camus". Ministère de l'éducation nationale. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- "Enseignement primaire" (in French). Marie de Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Enseignement secondaire" (in French). Marie de Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Jumelages" (in French). Marie de Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

Sources

- Gagnière, Sylvain; Granier, J. (1973–1974). "Les carrelages du Château de Jean XXII à Châteauneuf-du-Pape". Mémoire de l'Académie de Vaucluse (in French). 7: 29–62.

- Maigret, Chantal (2002). "La tour Philippe le Bel 1303–2003: 700 ans d'histoire". Études Vauclusiennes (in French). 68: 5–22.

- Mistral, Frédéric (1879). Lou Trésor dou Félibrige ou Dictionnaire provençal-français (in French and Occitan). Vol. 1: A-F. Aix-en-Provence: J. Remondet-Aubin.

- Perrot, R.; Garnier, J. (1972). "Recherches historiques et archéologiques sur le château de Lhers, commune de Châteauneuf-du-Pape (Vaucluse)". Mémoire de l'Académie de Vaucluse (in French). 6: 43–123.

- Portes, Jean-Claude (1993). Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Mémoire d'un village (in French). Avignon: Alain Barthélemy. ISBN 978-2-87923-031-3.

- Schäfer, Karl Heinrich (1911). Die Ausgaben der Apostolischen Kammer unter Johann XXII. Nebst den Jahresbilanzen von 1316–1375 (in German and Latin). Paderborn, Germany: F. Schöningh.

- Schäfer, Karl Heinrich, ed. (1914). Die ausgaben der Apostolischen kammer unter Benedikt XII, Klemens VI und Innocenz VI (1335–1362) (in German and Latin). Paderborn, Germany: F. Schöningh. OL 6653164M.

Further reading

- Rendu, Victor (1857). "Vignobles de Châteauneuf du Pape". Ampélographie Française comprenant la statistique: la description des meilleurs cépages, l'analyse chimique du sol et les procédés de culture et de vinification des principaux vignobles de la France (in French). Paris: V. Masson. pp. 101–111.

External links

- Marie de Châteauneuf-du-Pape Official site of the town hall.

- Fédération des syndicats des producteurs de Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The Federation of Wine Producers