Frilled shark

The frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) and the southern African frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus africana) are the two extant species of shark in the family Chlamydoselachidae. The frilled shark is considered a living fossil, because of its primitive, anguilliform (eel-like) physical traits, such as a dark-brown color, amphistyly (the articulation of the jaws to the cranium), and a 2.0 m (6.6 ft)–long body, which has dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins located towards the tail. The common name, frilled shark, derives from the fringed appearance of the six pairs of gill slits at the shark's throat.

| Frilled shark Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Superorder: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Hexanchiformes |

| Family: | Chlamydoselachidae |

| Genus: | Chlamydoselachus |

| Species: | C. anguineus |

| Binomial name | |

| Chlamydoselachus anguineus Samuel Garman, 1884 | |

| |

| Range of the frilled shark | |

The two species of frilled shark are distributed throughout regions of the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans, usually in the waters of the outer continental shelf and of the upper continental slope, where the sharks usually live near the ocean floor, near biologically productive areas of the ecosystem. To live on a diet of cephalopods, smaller sharks, and bony fish, the frilled shark practices diel vertical migration to feed at night at the surface of the ocean. When hunting food, the frilled shark moves like an eel, bending and lunging to capture and swallow whole prey with its long and flexible jaws, which are equipped with 300 recurved, needle-like teeth.[2]

Reproductively, the two species of frilled shark, C. anguineus and C. africana, are aplacental viviparous animals, born of an egg, without a placenta to the mother shark. Contained within egg capsules, the shark embryos develop in the body of the mother shark; at birth, the infant sharks emerge from their egg capsules in the uterus, where they feed on yolk. Although it has no distinct breeding season, the gestation period of the frilled shark can be up to 3.5 years long, to produce a litter of 2–15 shark pups. Usually caught as bycatch in commercial fishing, the frilled shark has some economic value as a meat and as fishmeal; and has been caught from depths of 1,570 m (5,150 ft), although its occurrence is uncommon below 1,200 m (3,900 ft); whereas in Suruga Bay, Japan, the frilled shark commonly occurs at depths of 50–200 m (160–660 ft).[3]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The zoologist Ludwig Döderlein first identified, described, and classified the frilled shark as a discrete species of shark. After three years (1879–1881) of marine research in Japan, Döderlein took two specimen sharks to Vienna, but lost the taxonomic manuscript of the research. Three years later, in the Bulletin of the Essex Institute (vol. XVI, 1884) the zoologist Samuel Garman published the first taxonomy of the frilled shark, based upon his observations, measurements, and descriptions of a 1.5-metre (4 ft 11 in)–long female shark from Sagami Bay, Japan. In the article "An Extraordinary Shark" Garman classified the new species of shark within its own genus and family, and named it Chlamydoselachus anguineus (eel-like shark with frills).[4][5] The Graeco–Latin nomenclature of the frilled shark derives from the Greek chlamy (frill) and selachus (shark), and the Latin anguineus (like an eel);[2] besides its common name, the frilled shark also is known as the "lizard shark" and as the "scaffold shark".[1][6]

The frilled-shark is considered a "living fossil", because its family lineage dates to the Carboniferous period.[7] Initially, marine scientists considered the frilled shark a living, evolutionary representative of the extinct elasmobranchii subclass of cartilaginous fish (rays, sharks, skates, sawfish), because the shark's body featured primitive anatomic traits, such as long jaws with trident-shaped, multi-cusp teeth; amphistyly, the direct articulation of the jaws to the cranium, at a point behind the eyes; and a quasi-cartilaginous notochord (a proto-spinal-column) composed of indistinct vertebrae.[8] From that anatomy, Garman proposed that the frilled shark was related to the cladodont sharks of the Cladoselache genus that existed during the Devonian period (419–359 mya) in the Palaeozoic era (541–251 mya). In contrast to Garman's thesis, the ichthyologist Theodore Gill and the paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, suggested that the frilled shark's evolutionary tree indicated relation to the Hybodontiformes (hybodonts), which were the dominant species of shark during the Mesozoic era (252–66 mya); and Cope categorized the Chlamydoselachus anguineus species to the fossil genus Xenacanthus that existed from the late Devonian period to the end of the Triassic period of the Mesozoic era.[9][10]

The anatomic traits of body, muscle, and skeleton phylogenically include the frilled shark to the neoselachian clade (modern sharks and rays) which relates it to the cow shark, in the order Hexanchiformes. In addition, a genetic analysis conducted by researchers in 2016 may also suggest that the species is part of the order Hexanchiformes.[11] Nonetheless, as a systematist of biology, the ichthyologist Shigeru Shirai proposed the Chlamydoselachiformes taxonomic order exclusively for the C. anguinesis and the C. africana species of frilled sharks.[8][10] As a marine animal, the frilled shark is a living fossil because of its relatively unchanged anatomy and physique, since first appearing in the primeval seas of the Late Cretaceous (c. 95 mya) and the Late Jurassic (150 mya) epochs.[12][5] In evolutionary terms, the frilled shark is an animal species of recent occurrence in the natural history of the Earth; the earliest discoveries of the fossilized teeth of the Chlamydoselachus anguineus species of shark date to the early Pleistocene epoch (2.58–11.70 mya).[13] In 2009, marine biologists identified, described, and classified the Chlamydoselachus africana (southern African frilled shark) of the Atlantic waters of southern Angola and of southern Namibia as a species of frilled shark different from the Chlamydoselachus anguineus identified in 1884.[14]

Habitat and distribution

The habitats of the frilled shark include the waters of the outer continental shelf and the upper-to-middle continental slope, favoring upwellings and other biologically productive areas.[2] Usually, the shiver lives close to the ocean floor,[1] yet its diet of cephalopods, smaller sharks, and bony fish, indicates that the frilled shark practices diel vertical migration, and swims up to feed at night at the surface of the ocean.[15][2] In their Atlantic- and Pacific-ocean habitats, frilled sharks practice spatial segregation determined by the individual size, the sex, and the reproductive condition of each shark in the shiver.[16] In Suruga Bay, on the Pacific coast of Honshu, Japan, the frilled shark is most common at the depth of 50–200 m (160–660 ft), except in the August-to-November period, when the temperature at the 100 m (330 ft) water-layer exceeds 15 °C (59 °F), and then the sharks swim into deeper, cooler water.[17][16]

In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, the frilled shark occurs off northern Norway, northern Scotland, and western Ireland, ranging from France to Morocco, the archipelago of Madeira, and the coast of Mauritania, in northwest Africa.[18] In the central Atlantic Ocean, the frilled shark has been caught along the region of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, ranging from north of the Azores islands to the Rio Grande Rise, off southern Brazil, and the Vavilov Ridge, off West Africa. Frilled sharks tend to be very solitary organisms, interacting with multiple individuals of their kind is rare. However, in the late 2000s a large capture was made over an underwater seamount of the Mid-Atlantic ridge, hauling in over 30 frilled sharks. The mass capture of a wide variety of male and female specimens emphasized these seamounts as a location for the mating of the species.[19] In the western Atlantic, the frilled shark occurs in the waters of New England and Georgia, in the US, and in the waters of Suriname, in the northeastern coast of South America.[20][19][14]

In the western Pacific Ocean, the frilled shark ranges from southeastern Honshu, Japan, north to Taiwan, off the coast of China, to the coast of New South Wales, Australia, and the islands of Tasmania and New Zealand. In the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, the frilled shark occurs in the regional waters of Hawaii and the coast of California, in the US, and the northern coast of Chile, in western South America.[1][18] Although it has been caught at the depth of 1,570 m (5,150 ft), the frilled shark usually does not occur deeper than 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[1][6]

Description

_by_OpenCage.jpg.webp)

The eel-like bodies of C. anguineus and C. africana differ anatomically; C. anguineus has a longer head and shorter gill slits, a spinal column with more vertebrae (160–171 vs. 147), and a lower-intestine spiral valve with more turns (35–49 vs. 26–28) than does C. africana.[14] The skin color of either species ranges from uniformly dark-brown to uniformly grey.[2] In addition, C. anguineus has smaller pectoral fins than C. africana, and the mouth is narrower.[21] The recorded, maximum body-length of a male frilled shark is 1.7 m (5.6 ft), and the recorded, maximum body-length of a female frilled shark is 2.0 m (6.6 ft).[2]

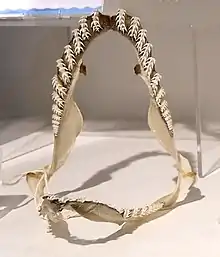

The head of the frilled shark is broad and flat, with a short, rounded snout. The nostrils are vertical slits, separated by a flap of skin that forms the incurrent opening and the excurrent opening. The moderately large eyes are horizontal ellipsoids, which have no nictitating membrane, which is a protective, third-eyelid. Ligaments articulate the long jaws to the cranium, and the corners of the mouth have neither furrows nor folds. The jaws contain 300 trident-shaped teeth, each needle-tooth has a cusp and two cusplets;[2][15] the rows of teeth are widely spaced, with 19–28 tooth rows in the upper jaw, and 21–29 tooth rows in the lower jaw.[4][14] Frilled sharks are able to open jaws and devour food sources that are considerably greater than that of their size, this is a physical trait that is present in gulper eels and viperfish.[21] At the throat, there are six pairs of long gill slits; the first pair of gill slits form a collar, while the extended tips of the gill filaments create a fleshy frill, hence, the frilled shark name of this fish.[4]

The pectoral fins are short and rounded; the single, small dorsal fin has a rounded margin, and is positioned at the far end of the body, approximately opposite the anal fin. The pelvic and the anal fins are large, broad, and rounded, and are positioned to the tail-end of the frilled shark's body. The very long caudal fin is a triangular tail that has neither a lower lobe nor a ventral notch in the upper lobe, and has a margin equipped with sharp, chisel-shaped dermal denticles, which the shark can enlarge.[4] The underside of the shark's eel-like body features a pair of long, thick folds of skin, separated by a groove, which run the length of the belly; the function of the ventral skin-folds is unknown.[4] In the female frilled shark, the mid-section is of the body longer, with the pelvic fins located closer to the anal fin.[15][22]

Biology and ecology

A cartilaginous skeleton and a large liver (filled with low-density lipids) are the mechanical means with which the frilled shark controls and maintains its buoyancy in the deep waters of the ocean.[15] The shark has an open, lateral-line organ system featuring mechanoreceptor hair cells in grooves exposed to the ocean environment; such a basal clade configuration enhances the frilled shark's perception and detection of changes in the movement, the vibration, and the pressure of the surrounding water.[15][23] Like all animals, the frilled shark is afflicted by parasites, such as the Monorygma tapeworm, the trematoda flatworm, the Otodistomum veliporum,[24] and the Mooleptus rabuka nematode;[25] and by predators, such as other sharks, as indicated by missing tail-tips lost to a hungry attacker.[16]

In New Zealand, the Takatika Grit, in the Chatham Islands, yielded frilled-shark, bird, and conifer-cone fossils that dated to the time of the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (66.043 ± 0.011 mya)[26] which suggested that the sharks lived inland, in shallow bodies of water far from the ocean. The shallow-water frilled shark had larger, stronger teeth, suitable for eating mollusks; scarcity and plenty of food are indicated in the tooth's morphology of sharper points (cusps) oriented into the mouth. From the Late Paleocene epoch (66–56 mya) until the contemporary era, other species of sharks out-matched the Chlamydoselachus sharks in competition for feeding grounds and living space, which restricted their geographic distribution to the deep-water ocean. Regarding the frilled shark's survival of the mass-extinction event which occurred at the Cretaceous–Paleogene time-boundary, one hypothesis proposes that the sharks survived in bodies of shallow water, both inland and on the continental shelf; afterwards, the frilled shark migrated to deep-water habitats.[27]

Diet

The frilled shark eats a diet of cephalopods, sea slugs, smaller sharks, and bony fish;[2] 60 percent of the diet is composed of squid varieties, such as the Chiroteuthis, the Histioteuthis, and the Onychoteuthis, the Sthenoteuthis and the Todarodes;[17] and other sharks, as indicated by the stomach contents of a 1.6 m (5.2 ft)–long frilled shark which had swallowed a 590 g (1.30 lb) Japanese catshark (Apristurus japonicus).[15] The high tendency to primarily consume the squids in their habitat can be supported by the frequent observation of beak remnants left behind during digestive processes.[17] Because frilled sharks live on the ocean floor, they may also feed on carrion floating down from the surface.[28]

In hunting and eating prey that are tired or exhausted or dying (after spawn),[17] the frilled shark's physiology suggests that it may curve its anguilline body, and brace its rear fins against the water, for leverage to effect a rapid-strike bite that captures the prey.[15] The wide gape of the distended, long jaws allows devouring whole prey that are more than half the size of the frilled shark, itself.[2] The jaws' 300 recurved teeth (19–28 upper rows and 21–29 lower rows) readily snag and capture the soft body and tentacles of a cephalopod, especially with the rows of trident-shaped teeth are rotated outwards, when the jaws are open and protruded.[4] Moreover, unlike the strong bite of sharks with an underslung jaw attached below the cranium,[29] the frilled shark has a relatively weak bite, because of the limited leverage and force possible with long jaws that are directly articulated to the cranium, at a point behind the eyes.[29]

The behavior of captive specimen sharks suggests that the frilled shark also hunts with its mouth open, by using the dark-and-light contrast of white teeth and darkness to lure prey into its gaping maw;[14] and also hunts with negative pressure, to suck prey into its maw.[15] Forensic examination of frilled sharks' revealed little-to-no food in their stomachs, which suggests that the frilled shark either has a fast-rate of digestion or goes hungry in the long intervals between feedings.[17]

Reproduction

The extant species of frilled shark, C. anguineus and C. africana, do not have a defined breeding season, because their oceanic habitats register no seasonal influence from the ocean's surface;[16] the male shark reaches sexual maturity when he is 1.0–1.2 m (3.3–3.9 ft) long, and the female shark reaches sexual maturity when she is 1.3–1.5 m (4.3–4.9 ft) long.[1] The mature female shark has two ovaries and a uterus, which is in the right side of her body; ovulation occurs fortnightly; and pregnancy ceases vitellogenesis (yolk formation) and the production of new ova.[16] Both ovulated eggs and early-stage shark embryos are enclosed in chondrichthyes, ellipsoid egg-cases made of a thin, golden-brown membrane.[2]

Reproductively, the frilled shark is an ovoviviparous animal born from an encapsulated egg retained within the mother shark's uterus. During gestation, the shark embryos develop in membranous egg-cases contained within the body of the mother shark, when the infant sharks emerge from their egg capsules in the uterus they feed on yolk until birth. The frilled-shark embryo is 3.0 cm (1.2 in) long, has a pointed head, slightly developed jaws, nascent external gills, and possesses all fins. The growth of the jaw for elasmobranchs seem to begin early in the embryonic stage, however, it has been observed not to be the case for frilled sharks. The elongation of the jaws seemed to begin later in embryonic development. This leads to some studies suggesting that the terminal position of their mouth, due to anterior elongation of the jaw, is a derived trait instead of ancestral.[30] When the embryo is 6–8 cm (2.4–3.1 in) long, the mother shark expels the egg capsule, at which developmental stage the frilled shark's external gills are developed.[16][31] Throughout embryonic development, the size of the yolk sac remains constant, until the shark embryo is 40 cm (16 in) long, whereupon the sac shrinks until disappearing when the embryo has grown to 50 cm (20 in) in length. In the course of pregnancy, the embryo's average rate-of-growth is 1.40 cm (0.55 in) per month until birth, when the shark pups are 40–60 cm (16–24 in) long, therefore, the frilled shark's gestation period can be as long as 3.5 years;[16][15] at birth, a frilled shark's litter comprises 2–15 pups, with an average litter comprises 6.0 pups.[2]

Shark and human interaction

In pursuit of food, the frilled shark usually is a bycatch of commercial fishing, accidentally caught in the nets used for trawl-, gillnet-, and longline-fishing.[1] In Japan, at Suruga Bay, the frilled shark is usually caught in the gillnets used to catch sea bream and gnomefish, and in the trawl nets used to catch shrimp in the mid-waters of the ocean. Despite being a nuisance fish that damages fishing nets, the economic and commercial value of the frilled shark is as fishmeal and as meat.[16]

In 2004, marine biologists first observed the frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) at the depth of 873.55 m (2,866.0 ft), in its deep-water habitat at the Blake Plateau, off the southeastern coast of the U.S.[20] In 2007, a Japanese fisherman caught a 1.6 m (5.2 ft)–long female frilled shark at the surface of the ocean and delivered it to the Awashima Marine Park, at Shizuoka city, where the shark died after hours of captivity.[32] In 2014, a trawler fishing-boat caught a 1.5 m (4.9 ft)–long frilled shark in 1.0 km (3,300 ft)–deep water at Lakes Entrance, Victoria, Australia; later, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) confirmed that the shark was a Chlamydoselachus anguineus, an eel-like shark with a frill.[33]

In 2016, consequent to the depletion of food sources caused by commercial overfishing of the feeding areas of the shark's deep-water habitat, and because of the shark's slow rate of reproduction, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classified the frilled shark as a fish species under near-threat of extinction, and then reclassified it as a species of Least Concern of extinction.[1] In 2018, the New Zealand Threat Classification System identified the frilled shark as an animal "At Risk — Naturally Uncommon", not easily found living in the wild.[34]

See also

- List of sharks

References

- Smart, J.J.; Paul, L.J.; Fowler, S.L. (2016). "Chlamydoselachus anguineus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41794A68617785. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41794A68617785.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Ebert, D.A. (2003). Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras of California. University of California Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0-520-23484-7.

- Bray, Dianne J. (2011). "Frill Shark, Chlamydoselachus anguineus". FishesofAustralia.net.au. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Garman, S. (January 17, 1884). "An Extraordinary Shark". Bulletin of the Essex Institute. 16: 47–55.

- Bright, M. (2000). The Private Life of Sharks: The Truth Behind the Myth. Stackpole Books. pp. 210–213. ISBN 0-8117-2875-7.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2010). "Chlamydoselachus anguineus" in FishBase. April 2010 version.

- "The Frilled Shark—The Oldest Living Type of Vertebrates". Scientific American. 56 (9): 130. 1887-02-26. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican02261887-130a. ISSN 0036-8733.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1977). "Phyletic Relationships of Living Sharks and Rays". American Zoologist. 17 (2): 303–322. doi:10.1093/icb/17.2.303.

- Garman, S.; Gill, T. (March 21, 1884). "'The Oldest Living Type of Vertebrata,' Chlamydoselachus". Science. 3 (59): 345–346. doi:10.1126/science.ns-3.59.345-a. PMID 17838181.

- Martin, R.A. Chlamydoselachiformes: Frilled Sharks. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 25, 2010.

- Bustamante, Carlos; Bennett, Michael B.; Ovenden, Jennifer R. (2016-01-01). "Genetype and phylogenomic position of the frilled shark Chlamydoselachus anguineus inferred from the mitochondrial genome". Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 1 (1): 18–20. doi:10.1080/23802359.2015.1137801. ISSN 2380-2359. PMC 7799599. PMID 33473392.

- Martin, R.A. The Rise of Modern Sharks. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 25, 2010.

- Marsili, S. (2007). Analisi systematic, paleoecological e paleobiogeographical Della selaciofauna polio-Pleistocene del Mediterraneo.

- Ebert, D.A.; Compagno, L.J.V. (2009). "Chlamydoselachus africana, a new species of frilled shark from southern Africa (Chondrichthyes, Hexanchiformes, Chlamydoselachidae)". Zootaxa. 2173: 1–18. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2173.1.1.

- Martin, R.A. Deep Sea: Frilled Shark. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 25, 2010.

- Tanaka, S.; Shiobara, Y.; Hioki, S.; Abe, H.; Nishi, G.; Yano, K. & Suzuki, K. (1990). "The reproductive biology of the frilled shark, Chlamydoselachus anguineus, from Suruga Bay, Japan". Japanese Journal of Ichthyology. 37 (3): 273–291.

- Kubota, T.; Shiobara, Y. & Kubodera, T. (January 1991). "Food habits of the frilled shark Chlamydoselachus anguineus collected from Suruga bay, central Japan". Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 57 (1): 15–20. doi:10.2331/suisan.57.15.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 14–15. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- Kukuev, E.I.; Pavlov, V.P. (2008). "The First Case of Mass Catch of a Rare Frill Shark Chlamydoselachus anguineus over a Seamount of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge". Journal of Ichthyology. 48 (8): 676–678. doi:10.1134/S0032945208080158. S2CID 281370.

- Jenner, J. (2004). Estuary to the Abyss: Excitement, Realities, and "Bubba". NOAA Ocean Explorer. Retrieved on April 25, 2010.

- Ebert, David A.; Compagno, Leonard J. V. (2009). "Chlamydoselachus Africana, A New Species Of Frilled Shark From Southern Africa (Chondrichthyes, Hexanchiformes, Chlamydoselachidae)". Zootaxa. 2173: 1–18. doi:10.5281/zenodo.189264.

- Last, P.R.; J.D. Stevens (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- Martin, R.A. Hearing and Vibration Detection. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 25, 2010.

- Collett, R. (1897). "On Chlamydoselacnus anguineus Garman. A remarkable shark found in Norway 1896". Christiania. 11: 1–17.

- Machida, M.; Ogawa, K. & Okiyama, M. (1982). "A new nematode (Spirurida, Physalopteridae) from frill shark of Japan". Bulletin of the National Science Museum Series A (Zoology). 8 (1): 1–5.

- Renne; et al. (2013). "Time Scales of Critical Events Around the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary". Science. 339 (6120): 684–7. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1230492. PMID 23393261. S2CID 6112274.

- Consoli, Christopher, P. (2008). "A Rare Danian (Paleocene) Chlamydoselachus (Chondricthyes: Elasmobranchii) from the Takatika Grit, Chatham Islands, New Zealand". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (2): 285–290. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[285:ardepc]2.0.co;2.

- Lashaway, Aubrey. "ADW: Chlamydoselachus anguineus: INFORMATION". Animaldiversity.org. Retrieved 2022-08-23.

- Moss, S. (1977). "Feeding Mechanisms in Sharks". American Zoologist. 17 (2): 355–364. doi:10.1093/icb/17.2.355.

- López‐Romero, Faviel A.; Klimpfinger, Claudia; Tanaka, Sho; Kriwet, Jürgen (2020). "Growth trajectories of prenatal embryos of the deep‐sea shark Chlamydoselachus anguineus (Chondrichthyes)". Journal of Fish Biology. 97 (1): 212–224. doi:10.1111/jfb.14352. ISSN 0022-1112. PMC 7497067. PMID 32307702.

- Nishikawa, T. (1898). "Notes on some embryos of Chlamydoselachus anguineus, Garm". Annotationes Zoologicae Japonenses. 2: 95–102.

- Japanese Marine Park Captures Rare 'Living Fossil' Frilled Shark; Pictures of a Live Specimen 'Extremely Rare'. Underwatertimes.com. January 24, 2007. Retrieved on April 25, 2010.

- "'Horrific' Rarely-sighted Frilled Shark Caught off south-east Victoria". The Age. Melbourne, Australia: Fairfax Media. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand Chondrichthyans (Chimaeras, Sharks and Rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 9. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.

External links

- ABC News video

- Chlamydoselachus anguineus, Frilled shark at FishBase

- Deep Sea: Frilled Shark at ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research

- Frilled Shark - Video at Check123 - Video Encyclopedia