Cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is encipherment. To encipher or encode is to convert information into cipher or code. In common parlance, "cipher" is synonymous with "code", as they are both a set of steps that encrypt a message; however, the concepts are distinct in cryptography, especially classical cryptography.

Codes generally substitute different length strings of character in the output, while ciphers generally substitute the same number of characters as are input. There are exceptions and some cipher systems may use slightly more, or fewer, characters when output versus the number that were input.

Codes operated by substituting according to a large codebook which linked a random string of characters or numbers to a word or phrase. For example, "UQJHSE" could be the code for "Proceed to the following coordinates." When using a cipher the original information is known as plaintext, and the encrypted form as ciphertext. The ciphertext message contains all the information of the plaintext message, but is not in a format readable by a human or computer without the proper mechanism to decrypt it.

The operation of a cipher usually depends on a piece of auxiliary information, called a key (or, in traditional NSA parlance, a cryptovariable). The encrypting procedure is varied depending on the key, which changes the detailed operation of the algorithm. A key must be selected before using a cipher to encrypt a message. Without knowledge of the key, it should be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to decrypt the resulting ciphertext into readable plaintext.

Most modern ciphers can be categorized in several ways

- By whether they work on blocks of symbols usually of a fixed size (block ciphers), or on a continuous stream of symbols (stream ciphers).

- By whether the same key is used for both encryption and decryption (symmetric key algorithms), or if a different key is used for each (asymmetric key algorithms). If the algorithm is symmetric, the key must be known to the recipient and sender and to no one else. If the algorithm is an asymmetric one, the enciphering key is different from, but closely related to, the deciphering key. If one key cannot be deduced from the other, the asymmetric key algorithm has the public/private key property and one of the keys may be made public without loss of confidentiality.

Etymology

The Roman number system was very cumbersome, in part because there was no concept of zero. The Arabic numeral system spread from the Arabic world to Europe in the Middle Ages. In this transition, the Arabic word for zero صفر (sifr) was adopted into Medieval Latin as cifra, and then into Middle French as cifre. This eventually led to the English word cipher (minority spelling cypher). One theory for how the term came to refer to encoding is that the concept of zero was confusing to Europeans, and so the term came to refer to a message or communication that was not easily understood.[1]

The term cipher was later also used to refer to any Arabic digit, or to calculation using them, so encoding text in the form of Arabic numerals is literally converting the text to "ciphers".

Versus codes

In non-technical usage, a "(secret) code" typically means a "cipher". Within technical discussions, however, the words "code" and "cipher" refer to two different concepts. Codes work at the level of meaning—that is, words or phrases are converted into something else and this chunking generally shortens the message.

An example of this is the commercial telegraph code which was used to shorten long telegraph messages which resulted from entering into commercial contracts using exchanges of telegrams.

Another example is given by whole word ciphers, which allow the user to replace an entire word with a symbol or character, much like the way Japanese utilize Kanji (meaning Chinese characters in Japanese) characters to supplement their language. ex "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" becomes "The quick brown 狐 jumps 上 the lazy 犬".

Ciphers, on the other hand, work at a lower level: the level of individual letters, small groups of letters, or, in modern schemes, individual bits and blocks of bits. Some systems used both codes and ciphers in one system, using superencipherment to increase the security. In some cases the terms codes and ciphers are also used synonymously to substitution and transposition.

Historically, cryptography was split into a dichotomy of codes and ciphers; and coding had its own terminology, analogous to that for ciphers: "encoding, codetext, decoding" and so on.

However, codes have a variety of drawbacks, including susceptibility to cryptanalysis and the difficulty of managing a cumbersome codebook. Because of this, codes have fallen into disuse in modern cryptography, and ciphers are the dominant technique.

Types

There are a variety of different types of encryption. Algorithms used earlier in the history of cryptography are substantially different from modern methods, and modern ciphers can be classified according to how they operate and whether they use one or two keys.

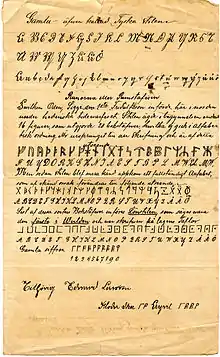

Historical

Historical pen and paper ciphers used in the past are sometimes known as classical ciphers. They include simple substitution ciphers (such as ROT13) and transposition ciphers (such as a Rail Fence Cipher). For example, "GOOD DOG" can be encrypted as "PLLX XLP" where "L" substitutes for "O", "P" for "G", and "X" for "D" in the message. Transposition of the letters "GOOD DOG" can result in "DGOGDOO". These simple ciphers and examples are easy to crack, even without plaintext-ciphertext pairs.[2][3]

Simple ciphers were replaced by polyalphabetic substitution ciphers (such as the Vigenère) which changed the substitution alphabet for every letter. For example, "GOOD DOG" can be encrypted as "PLSX TWF" where "L", "S", and "W" substitute for "O". With even a small amount of known or estimated plaintext, simple polyalphabetic substitution ciphers and letter transposition ciphers designed for pen and paper encryption are easy to crack.[4] It is possible to create a secure pen and paper cipher based on a one-time pad though, but the usual disadvantages of one-time pads apply.

During the early twentieth century, electro-mechanical machines were invented to do encryption and decryption using transposition, polyalphabetic substitution, and a kind of "additive" substitution. In rotor machines, several rotor disks provided polyalphabetic substitution, while plug boards provided another substitution. Keys were easily changed by changing the rotor disks and the plugboard wires. Although these encryption methods were more complex than previous schemes and required machines to encrypt and decrypt, other machines such as the British Bombe were invented to crack these encryption methods.

Modern

Modern encryption methods can be divided by two criteria: by type of key used, and by type of input data.

By type of key used ciphers are divided into:

- symmetric key algorithms (Private-key cryptography), where one same key is used for encryption and decryption, and

- asymmetric key algorithms (Public-key cryptography), where two different keys are used for encryption and decryption.

In a symmetric key algorithm (e.g., DES and AES), the sender and receiver must have a shared key set up in advance and kept secret from all other parties; the sender uses this key for encryption, and the receiver uses the same key for decryption. The Feistel cipher uses a combination of substitution and transposition techniques. Most block cipher algorithms are based on this structure. In an asymmetric key algorithm (e.g., RSA), there are two separate keys: a public key is published and enables any sender to perform encryption, while a private key is kept secret by the receiver and enables only that person to perform correct decryption.

Ciphers can be distinguished into two types by the type of input data:

- block ciphers, which encrypt block of data of fixed size, and

- stream ciphers, which encrypt continuous streams of data.

Key size and vulnerability

In a pure mathematical attack, (i.e., lacking any other information to help break a cipher) two factors above all count:

- Computational power available, i.e., the computing power which can be brought to bear on the problem. It is important to note that average performance/capacity of a single computer is not the only factor to consider. An adversary can use multiple computers at once, for instance, to increase the speed of exhaustive search for a key (i.e., "brute force" attack) substantially.

- Key size, i.e., the size of key used to encrypt a message. As the key size increases, so does the complexity of exhaustive search to the point where it becomes impractical to crack encryption directly.

Since the desired effect is computational difficulty, in theory one would choose an algorithm and desired difficulty level, thus decide the key length accordingly.

An example of this process can be found at Key Length which uses multiple reports to suggest that a symmetrical cipher with 128 bits, an asymmetric cipher with 3072 bit keys, and an elliptic curve cipher with 256 bits, all have similar difficulty at present.

Claude Shannon proved, using information theory considerations, that any theoretically unbreakable cipher must have keys which are at least as long as the plaintext, and used only once: one-time pad.[5]

See also

- Autokey cipher

- Cover-coding

- Encryption software

- List of ciphertexts

- Steganography

- Telegraph code

Notes

- Ali-Karamali, Sumbul (2008). The Muslim Next Door: The Qur'an, the Media, and That Veil Thing. White Cloud Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0974524566.

- Saltzman, Benjamin A. (2018). "Ut hkskdkxt: Early Medieval Cryptography, Textual Errors, and Scribal Agency (Speculum, forthcoming)". Speculum. 93 (4): 975. doi:10.1086/698861. S2CID 165362817.

- Janeczko, Paul B (2004). Top Secret.

- Stinson, p. 45

- "Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

References

- Richard J. Aldrich, GCHQ: The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency, HarperCollins July 2010.

- Helen Fouché Gaines, "Cryptanalysis", 1939, Dover. ISBN 0-486-20097-3

- Ibrahim A. Al-Kadi, "The origins of cryptology: The Arab contributions", Cryptologia, 16(2) (April 1992) pp. 97–126.

- David Kahn, The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing (ISBN 0-684-83130-9) (1967)

- David A. King, The ciphers of the monks - A forgotten number notation of the Middle Ages, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2001 (ISBN 3-515-07640-9)

- Abraham Sinkov, Elementary Cryptanalysis: A Mathematical Approach, Mathematical Association of America, 1966. ISBN 0-88385-622-0

- William Stallings, Cryptography and Network Security, principles and practices, 4th Edition

- Stinson, Douglas R. (1995), Cryptogtaphy / Theory and Practice, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-8521-0