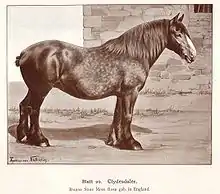

Clydesdale horse

The Clydesdale is a Scottish breed of draught horse. It is named for its area of origin, the Clydesdale or valley of the River Clyde, much of which is within the county of Lanarkshire.

| |

| Conservation status | |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Scotland |

| Standard | |

| Traits | |

| Weight | |

| Height | |

| Colour | |

The origins of the breed lie in the eighteenth century, when Flemish stallions were imported to Scotland and mated with local mares; in the nineteenth century, Shire blood was introduced.[6]: 50 The first recorded use of the name "Clydesdale" for the breed was in 1826; the horses spread through much of Scotland and into northern England. After the breed society was formed in 1877, thousands of Clydesdales were exported to many countries of the world, particularly to Australia and New Zealand. In the early twentieth century numbers began to fall, both because many were taken for use in the First World War, and because of the increasing mechanisation of agriculture. By the 1970s, the Rare Breeds Survival Trust considered the breed vulnerable to extinction. Numbers have since increased slightly.

It is a large and powerful horse, although now not as heavy as in the past.[6]: 50 It was traditionally used for draught power, both in farming and in road haulage. It is now principally a carriage horse. It may be ridden or driven in parades or processions; some have been used as drum horses by the Household Cavalry, while in the United States the Anheuser-Busch brewery uses a matched team of eight for publicity.[6]: 50

History

The Clydesdale takes its name from Clydesdale, the old name for Lanarkshire, noted for the River Clyde.[7] In the mid-18th century, Flemish stallions were imported to Scotland and bred to local mares, resulting in foals that were larger than the existing local stock. These included a black unnamed stallion imported from England by a John Paterson of Lochlyloch and an unnamed dark-brown stallion owned by the Duke of Hamilton.[8]

Another prominent stallion was a 165 cm (16.1 h) coach horse stallion of unknown lineage named Blaze. Written pedigrees were kept of these foals beginning in the early nineteenth century, and in 1806, a filly, later known as "Lampits mare" after the farm name of her owner, was born that traced her lineage to the black stallion. This mare is listed in the ancestry of almost every Clydesdale living today. One of her foals was Thompson's Black Horse (known as Glancer), which was to have a significant influence on the Clydesdale breed.[8]

The first recorded use of the name "Clydesdale" in reference to the breed was in 1826 at an exhibition in Glasgow.[9] Another theory of their origin, that of them descending from Flemish horses brought to Scotland as early as the 15th century, was also promulgated in the late 18th century. However, even the author of that theory admitted that the common story of their ancestry is more likely.[10]

A system of hiring stallions between districts existed in Scotland, with written records dating back to 1837.[7] This programme consisted of local agriculture improvement societies holding breed shows to choose the best stallion, whose owner was then awarded a monetary prize. The owner was then required, in return for additional monies, to take the stallion throughout a designated area, breeding to the local mares.[11] Through this system and by purchase, Clydesdale stallions were sent throughout Scotland and into northern England.

Through extensive crossbreeding with local mares, these stallions spread the Clydesdale type throughout the areas where they were placed, and by 1840, Scottish draught horses and the Clydesdale were one and the same.[9] In 1877, the Clydesdale Horse Society of Scotland was formed, followed in 1879 by the American Clydesdale Association (later renamed the Clydesdale Breeders of the USA), which served both U.S. and Canadian breed enthusiasts. The first American stud book was published in 1882.[7] In 1883, the short-lived Select Clydesdale Horse Society was founded to compete with the Clydesdale Horse Society. It was started by two breeders dedicated to improving the breed, who also were responsible in large part for the introduction of Shire blood into the Clydesdale.[12]

Large numbers of Clydesdales were exported from Scotland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with 1617 stallions leaving the country in 1911 alone. Between 1884 and 1945, export certificates were issued for 20,183 horses. These horses were exported to other countries in the British Empire, as well as North and South America, continental Europe, and Russia.[8]

The First World War had the conscription of thousands of horses for the war effort, and after the war, breed numbers declined as farms became increasingly mechanised. This decline continued between the wars. Following the Second World War, the number of Clydesdale breeding stallions in England dropped from more than 200 in 1946 to 80 in 1949. By 1975, the Rare Breeds Survival Trust considered them vulnerable to extinction,[13] meaning fewer than 900 breeding females remained in the UK.[14]

Many of the horses exported from Scotland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries went to Australia and New Zealand.[13] In 1918, the Commonwealth Clydesdale Horse Society was formed as the association for the breed in Australia.[15] Between 1906 and 1936, Clydesdales were bred so extensively in Australia that other draught breeds were almost unknown.[16] By the late 1960s, it was noted that "Excellent Clydesdale horses are bred in Victoria and New Zealand; but, at least in the former place, it is considered advisable to keep up the type by frequent importations from England."[17] Over 25,000 Clydesdales were registered in Australia between 1924 and 2008.[18] The popularity of the Clydesdale led to it being called "the breed that built Australia".[12]

In the 1990s numbers began to rise. By 2005, the Rare Breeds Survival Trust had moved the breed to "at risk" status,[13] meaning that there were fewer than 1500 breeding females in the UK.[14] By 2010 it had been moved back to "vulnerable".[19] In 2010 the Clydesdale was listed as "watch" by the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, meaning that fewer than 2500 horses were registered annually in the USA, and there were fewer than 10,000 worldwide.[20] In 2010 the worldwide population was estimated to be 5000,[21] with around 4000 in the US and Canada,[13] 800 in the UK,[8] and the rest in other countries, including Russia, Japan, Germany, and South Africa.[12]

Characteristics

The conformation of the Clydesdale has changed greatly throughout its history. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was a compact horse smaller than the Shire, Percheron, and Belgian Draught. Beginning in the 1940s, breeding animals were selected to produce taller horses that looked more impressive in parades and shows. Today, the Clydesdale stands 162 to 183 cm (16.0 to 18.0 h) high and weighs 820 to 910 kg (1800 to 2000 lb).[13] Some mature males are larger, standing taller than 183 cm and weighing up to 1000 kg (2200 lb). The breed has a straight or slightly convex facial profile,[22] broad forehead, and wide muzzle.

It is well-muscled and strong, with an arched neck, high withers, and a sloped shoulder. Breed associations pay close attention to the quality of the hooves and legs, as well as the general movement. Their gaits are active, with clearly lifted hooves and a general impression of power and quality.[13] Clydesdales are energetic, with a manner described by the Clydesdale Horse Society as a "gaiety of carriage and outlook".[8]

Clydesdales have been identified to be at risk for chronic progressive lymphedema, a disease with clinical signs that include progressive swelling, hyperkeratosis, and fibrosis of distal limbs that is similar to chronic lymphedema in humans.[23] Another health concern is a skin condition on the lower leg where feathering is heavy. Colloquially called "Clyde's itch", it is thought to be caused by a type of mange. Clydesdales are also known to develop sunburn on any pink (unpigmented) skin around their faces.[24]

Clydesdales are usually bay in colour, but a Sabino like pattern (currently an untestable KIT mutation), black, grey, and chestnut also occur. Most have white markings, including white on the face, feet, and legs, and occasional body spotting (generally on the lower belly). They also have extensive feathering on their lower legs.[13] Sabino like ticking, body spotting, and extensive white markings are thought to be the result of sabino genetics. Some Clydesdale breeders want white face and leg markings without the spotting on the body.[25]

To attempt getting the ideal set of markings, they often breed horses with only one white leg to horses with four white legs and sabino ticking on their bodies. On average, the result is a foal with the desired amount of white markings.[25] Clydesdales do not have the Sabino 1 (SB1) gene responsible for causing sabino expressions in many other breeds, and researchers theorise that several other genes are responsible for these patterns.[26]

Many buyers pay a premium for bay and black horses, especially those with four white legs and white facial markings. Specific colours are often preferred over other physical traits, and some buyers even choose horses with soundness problems if they have the desired colour and markings. Sabino like horses are not preferred by buyers, despite one draught-breed writer theorising that they are needed to keep the desired coat colours and texture.[27] Breed associations, however, state that no colour is bad, and that horses with roaning and body spots are increasingly accepted.[28]

Uses

The Clydesdale was originally used for agriculture, hauling coal in Lanarkshire, and heavy hauling in Glasgow.[7] Today, Clydesdales are still used for draught purposes, including agriculture, logging, and driving. They are also shown and ridden, as well as kept for pleasure. Clydesdales are known to be the popular breed choice with carriage services and parade horses because of their white, feathery feet.[13]

Along with carriage horses, Clydesdales are also used as show horses. They are shown in lead line and harness classes at county and state fairs, as well as national exhibitions. Some of the most famous members of the breed are the teams that make up the hitches of the Budweiser Clydesdales. These horses were first owned by the Budweiser Brewery at the end of Prohibition in the United States, and have since become an international symbol of both the breed and the brand. The Budweiser breeding programme, with its strict standards of colour and conformation, have influenced the look of the breed in the United States to the point that many people believe that Clydesdales are always bay with white markings.[13]

Some Clydesdales are used for riding and can be shown under saddle, as well as being driven. Due to their calm disposition, they have proven to be very easy to train and capable of making exceptional trail horses. Clydesdales and Shires are used by the British Household Cavalry as drum horses, leading parades on ceremonial and state occasions. The horses are eye-catching colours, including piebald, skewbald, and roan. To be used for this purpose, a drum horse must stand a minimum of 173 cm (17 h). They carry the Musical Ride Officer and two silver drums weighing 56 kilograms (123 lb) each.[29][30]

In the late nineteenth century, Clydesdale blood was added to the Irish Draught breed in an attempt to improve and reinvigorate that declining breed. However, these efforts were not seen as successful, as Irish Draught breeders thought the Clydesdale blood made their horses coarser and prone to lower leg faults.[31] The Clydesdale contributed to the development of the Gypsy Horse in Great Britain.[32] The Clydesdale, along with other draught breeds, was also used to create the Australian Draught Horse.[33] In the early twentieth century, they were often crossed with Dales Ponies, creating mid-sized draught horses useful for pulling commercial wagons and military artillery.[34]

References

- Barbara Rischkowsky, D. Pilling (eds.) (2007). List of breeds documented in the Global Databank for Animal Genetic Resources, annex to The State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 9789251057629. Accessed January 2017.

- Breed data sheet: Clydesdale / United Kingdom (Horse). Domestic Animal Diversity Information System of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed April 2020.

- Equine watchlist. Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Accessed April 2020.

- Valerie Porter, Lawrence Alderson, Stephen J.G. Hall, D. Phillip Sponenberg (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding (sixth edition). Wallingford: CABI. ISBN 9781780647944.

- Élise Rousseau, Yann Le Bris, Teresa Lavender Fagan (2017). Horses of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691167206.

- Elwyn Hartley Edwards (2016). The Horse Encyclopedia. New York, New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 9781465451439.

- "Clydesdale". International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Breed History". Clydesdale Horse Society. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Hendricks, pp. 133–134

- Biddell, pp. 75–76

- McNeilage, p. 73

- Edwards, pp. 284–285

- Dutson, pp. 348–351

- "Watchlist". Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- "Our Purpose". Commonwealth Clydesdale Horse Society. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- "Our History - 1900 to 1930". Commonwealth Clydesdale Horse Society. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Hayes, p. 361

- "Our History - 1970 to present". Commonwealth Clydesdale Horse Society. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- "Watchlist - Equines". Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- "Conservation Priority Equine Breeds 2010" (PDF). American Livestock Breeds Conservancy. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- "Clydesdale horse". American Livestock Breeds Conservancy. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "The Clydesdale Horse - Breed Standards". Commonwealth Clydesdale Horse Society. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Chronic Progressive Lymphedema (CPL) in Draft Horses". University of California, Davis. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Commonwealth Clydesdale Horse Society of Australia - Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "Sabino spotting". American Paint Horse Association. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Brooks, Samantha; Ernest Bailey (2005). "Exon skipping in the KIT gene causes a sabino spotting pattern in horses". Mammalian Genome. 16 (11): 893–902. doi:10.1007/s00335-005-2472-y. PMID 16284805. S2CID 32782072.

- Roy, Bruce (16 August 2010). "Stable Talk". The Draft Horse Journal. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "The Modern Clydesdale". Clydesdale Horse Society. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Reid, Melanie (31 March 2010), "Digger, the horse who grew up to join the Army", The Sunday Times, retrieved 24 January 2011

- "The Drum Horse". The Household Cavalry. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Edwards, pp. 374–375

- Dutson, pp. 117–118

- "Foundation Breeds". Clydesdale & Heavy Horse Field Days Association Inc. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Dutson, p. 294

Further reading

- Biddell, Herman (1894). Heavy Horses: Breeds and Management. London, Vinton & Co.

- Dutson, Judith (2005). Storey's Illustrated Guide to 96 Horse Breeds of North America. Storey Publishing. ISBN 1-58017-613-5.

- Edwards, Elwyn Hartley (1994). The Encyclopedia of the Horse (1st American ed.). New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 1-56458-614-6.

- Hayes, Capt. M. Horace, FRCVS (2003) [1969]. Points of the Horse (7th Revised ed.). New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59333-000-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hendricks, Bonnie (2007). International Encyclopedia of Horse Breeds. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3884-8.

- McNeilage, Arch. (1904). "A Scottish Authority on the Premium System". In National Livestock Association of Canada (ed.). General convention, Issues 1–3. Government Printing Bureau.

- Smith, Donna Campbell (2007). The Book of Draft Horses: The Gentle Giants that Built the World. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-1-59228-979-0.