Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue (French pronunciation: [sɛ̃.dɔ.mɛ̃ɡ]) was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer specifically to the Spanish-held Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, now the Dominican Republic. The borders between the two were fluid and changed over time until they were finally solidified in the Dominican War of Independence in 1844.

Saint-Domingue Saint-Domingue | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1625–1804 | |||||||||

Flag before the French Revolution

Royal Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of France

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Colony of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Cap-Français (1711–1770) Port-au-Prince (1770–1804) 19°6′0″N 72°20′0″W | ||||||||

| Common languages | French, Creole French | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Colony | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1625–1643 | Louis XIII | ||||||||

• 1643–1715 | Louis XIV | ||||||||

• 1715–1774 | Louis XV | ||||||||

• 1774–1792 | Louis XVI | ||||||||

| Governor General | |||||||||

• 1691–1700 | Jean Du Casse (first) | ||||||||

• 1803–1804 | Jean Jacques Dessalines (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• First French settlement | 1625 | ||||||||

• Recognized | 1697 | ||||||||

| 1 January 1804 | |||||||||

| Currency | Saint-Domingue livre | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Haiti | ||||||||

| History of Haiti |

|---|

| Pre-Columbian Haiti (before 1492) |

| Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (1492–1625) |

| Saint-Domingue (1625–1804) |

| First Empire of Haiti (1804–1806) |

|

| North Haiti (1806–1820) |

|

| South Haiti (1806–1820) |

|

| Republic of Haiti (1820–1849) |

|

| Second Empire of Haiti (1849–1859) |

|

| Republic of Haiti (1859–1957) |

| Duvalier dynasty (1957–1986) |

| Anti-Duvalier protest movement |

| Republic of Haiti (1986–present) |

|

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

|

The French had established themselves on the western portion of the islands of Hispaniola and Tortuga by 1659. In the Treaty of Ryswick of 1697, Spain formally recognized French control of Tortuga Island and the western third of the island of Hispaniola.[1][2] In 1791, slaves and some Saint Dominican Creoles took part in the Vodou ceremony Bois Caïman and planned the Haitian Revolution.[3] The slave rebellion later allied with Republican French forces following the abolition of slavery in the colony in 1793, although this alienated the island's dominant slave-owning class. France controlled the entirety of Hispaniola from 1795 to 1802, when a renewed rebellion began. The last French troops withdrew from the western portion of the island in late 1803, and the colony later declared its independence as Haiti, its indigenous name, the following year.

Overview

Spain controlled the entire island of Hispaniola from the 1490s until the 17th century, when French pirates began establishing bases on the western side of the island. The official name was La Española, meaning "The Spanish (Island)". It was also called Santo Domingo, after Saint Dominic.[4]

The western part of Hispaniola was neglected by the Spanish authorities, and French buccaneers began to settle first on the island of Tortuga, then on the northwest of Hispaniola. Spain later ceded the entire western coast of the island to France, retaining the rest of the island, including the Guava Valley, today known as the Central Plateau.[4]

The French called their portion of Hispaniola Saint-Domingue, the French equivalent of Santo Domingo. The Spanish colony on Hispaniola remained separate, and eventually became the Dominican Republic, the capital of which is still named Santo Domingo.[4]

The Division of Hispaniola

When Christopher Columbus took possession of the island in 1492, he named it Insula Hispana, meaning "the Spanish island" in Latin.[5] As Spain conquered new regions on the mainland of the Americas (Spanish Main), its interest in Hispaniola waned, and the colony's population grew slowly. By the early 17th century, the island and its smaller neighbors, notably Tortuga, had become regular stopping points for Caribbean pirates. In 1606, the king of Spain ordered all inhabitants of Hispaniola to move close to Santo Domingo, to avoid interaction with pirates. Rather than secure the island, however, this resulted in French, English and Dutch pirates establishing bases on the now-abandoned north and west coasts of the island.

French buccaneers established a settlement on the island of Tortuga in 1625 before going to Grande Terre (mainland). At first they survived by pirating ships, eating wild cattle and hogs, and selling hides to traders of all nations. Although the Spanish destroyed the buccaneers' settlements several times, on each occasion they returned due to an abundance of natural resources: hardwood trees, wild hogs and cattle, and fresh water. The settlement on Tortuga was officially established in 1659 under the commission of King Louis XIV.

In 1665, French colonization of the islands Hispaniola and Tortuga entailed slavery-based plantation agricultural activity such as growing coffee and cattle farming. It was officially recognized by King Louis XIV. Spain tacitly recognized the French presence in the western third of the island in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick; the Spanish deliberately omitted direct reference to the island from the treaty, but they were never able to reclaim this territory from the French.[6]

The economy of Saint-Domingue became focused on slave-based agricultural plantations. Saint-Domingue's Black population quickly increased. They followed the example of neighboring Caribbean colonies in coercive treatment of the slaves. More cattle and slave agricultural holdings, coffee plantations and spice plantations were implemented, as well as fishing, cultivation of cocoa, coconuts, and snuff. Saint-Domingue quickly came to overshadow the previous colony in both wealth and population. Nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles," Saint-Domingue became the richest and most prosperous French colony in the West Indies, cementing its status as an important port in the Americas for goods and products flowing to and from France and Europe. Thus, the income and the taxes from slave-based sugar production became a major source of the French budget.

Among the first buccaneers was Bertrand d'Ogeron (1613 – 1676), who played a big part in the settlement of Saint-Domingue. He encouraged the planting of tobacco, which turned a population of buccaneers and freebooters, who had not acquiesced to royal authority until 1660, into a sedentary population. D'Ogeron also attracted many colonists from Martinique and Guadeloupe, including Jean Roy, Jean Hebert and his family, and Guillaume Barre and his family, who were driven out by the land pressure which was generated by the extension of the sugar plantations in those colonies. But in 1670, shortly after Cap-Français (later Cap-Haïtien) had been established, the crisis of tobacco intervened and a great number of places were abandoned. The rows of freebooting grew bigger; plundering raids, like those of Vera Cruz in 1683 or of Campêche in 1686, became increasingly numerous, and Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay, elder son of Jean Baptist Colbert and at the time Minister of the Navy, brought back some order by taking a great number of measures, including the creation of plantations of indigo and of cane sugar. The first sugar windmill was built in 1685.

On 22 July 1795, Spain ceded to France the remaining Spanish part of the island of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), in the second Treaty of Basel, ending the War of the Pyrenees. The people of the eastern part of Saint-Domingue (French Santo Domingo)[7][8][9] were opposed to the arrangements and hostile toward the French. The islanders revolted against their new masters and a state of anarchy ensued, leading to more French troops being brought in.

Until the mid-18th century, there were efforts made by the French Crown to found a stable French-European population in the colony, a difficult task because there were few European women there. From the 17th century to the mid-18th century, the Crown attempted to remedy this by sending women from France to Saint-Domingue and Martinique to marry the settlers.[10] However, these women were rumoured to be former prostitutes from La Salpêtrière and the settlers complained about the system in 1713, stating that the women sent were not suitable, a complaint that was repeated in 1743.[10] The system was consequently abandoned, and with it the plans for colonisation. In the later half of the 18th century, it became common and accepted that a Frenchman during his stay of a few years would cohabitate with a local black female.[10]

An early death among Europeans was very common due to diseases and conflicts; the French soldiers that Napoleon sent in 1802 to quell the revolt in Saint-Domingue were attacked by yellow fever during the Haitian Revolution, and more than half of the French army died of disease.[11]

The Saint-Domingue Colony

Saint-Domingue's Plantation Economy

Prior to the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the economy of Saint-Domingue gradually expanded, with sugar and, later, coffee becoming important export crops. After the war, which disrupted maritime commerce, the colony underwent rapid expansion. In 1767, it exported 72 million pounds of raw sugar and 51 million pounds of refined sugar, one million pounds of indigo, and two million pounds of cotton.[12] Saint-Domingue became known as the "Pearl of the Antilles" – one of the richest colonies in the world in the 18th-century French empire. It was the greatest jewel in imperial France's mercantile crown. By the 1780s, Saint-Domingue produced about 40 percent of all the sugar and 60 percent of all the coffee consumed in Europe. By 1789, Saint Domingue was made up of about 8,000 plantations ..., producing one-half of all the sugar and coffee that was consumed in Europe and the Americas.[13] This single colony, roughly the size of Hawaiʻi or Belgium, produced more sugar and coffee than all of the British West Indies colonies combined, generating enormous revenue for the French government and enhancing its power.

Between 1681 and 1791 the labor for these plantations was provided by an estimated 790,000 or 860,000 slaves,[14] accounting in 1783–1791 for a third of the entire Atlantic slave trade.[15] In addition, some Native Americans were enslaved in Louisiana and sent to Saint-Domingue, particularly in the wake of the Natchez revolt.[16] Between 1764 and 1771, the average annual importation of African slaves varied between 10,000 and 15,000; by 1786 it was about 28,000, and from 1787 onward, the colony received more than 30,000 slaves a year.[17]

The inability to maintain slave numbers without constant resupply from Africa meant that at all times, a majority of slaves in the colony were African-born, as specific conditions of slavery and exposure to tropical diseases such as yellow fever prevented the population from experiencing growth through natural increase.[18] Slave traders ventured along the Atlantic coast of Africa, buying slaves for plantation labor; most of the slaves they bought were war-captives and enslaved by an opposing African ethnic group.[19] The slaves that they purchased came from hundreds of different tribes; their languages often were mutually incomprehensible, and they learned Creole French to communicate.[20]

The slave population around 1789 totalled to 406,000 (according to Jacques Pierre Brissot) or 465,000, controlled by the Saint Dominican affranchi (ex-slave) and Creole of color population that numbered about 28,000 or 32,000[21][22][23] and Saint Dominican whites that numbered 40,000 or 45,000, which included the larger group of petits blancs (white commoners) consisting of Creoles of lighter complexions, French subjects, engagés (white indentured servants), and foreign European immigrants & refugees; and the tiny, exclusive group of grands blancs (white nobles) of whom the majority lived in France.[24][25][26][21]

There were numerous kinds of plantations in Saint-Domingue. Some planters produced indigo, cotton, and coffee; these plantations were small in scale, and usually only had 15-30 slaves, creating an intimate work environment. However, the most valuable plantations produced sugar. The average sugar plantation employed 300 slaves, and the largest sugar plantation on record employed 1400 slaves. These plantations took up only 14% of Saint-Domingue's cultivated land; comparatively, coffee was 50% of all cultivated land, indigo was 22%, and cotton only 5%. Because of the comparative investment requirement between sugar plantations and all other plantation types, there was a big economic gap between normal planters and sugar "lords."[22]

While grands blancs owned 800 large scale sugar plantations, the petits blancs and gens de couleur (people of color) owned 11,700 small scale plantations, of which petits blancs owned 5,700 plantations, counting 3,000 indigo, 2,000 coffee, and 700 cotton; the affranchis and Creoles of color owned 6,000 plantations that mainly produced coffee of which they held an economic monopoly.[21]

Plantation Conditions

%252C_plate_IV_-_BL.jpg.webp)

Planters took care to treat slaves well in the beginning of their time on the plantation, and they slowly integrated slaves into the plantation's labor system. On each plantation there was a black commander who supervised the other slaves on behalf of the planter, and the planter made sure not to favor one African ethnic group over others. Most slaves who came to Saint-Domingue worked in fields or shops; younger slaves often became household servants, and old slaves were employed as surveillants. Some slaves became skilled workmen, and they received privileges such as better food, the ability to go into town, and liberté des savanes (savannah liberty), a sort of freedom with certain rules. Slaves were considered to be valuable property, and slaves were attended by doctors who gave medical care when they were sick.[22]

To regularize slavery, in 1685 Louis XIV had enacted the Code Noir, which accorded certain rights to slaves and responsibilities to the master, who was obliged to feed, clothe and provide for the general well-being of his slaves.

The Code Noir also conferred affranchis (ex-slaves) full citizenship and gave complete civil equality with other French subjects.[21] Saint Domingue's Code Noir never outlawed interracial marriage, nor did it limit the amount of property a free person could give to affranchis. Saint Dominican Creoles of color and affranchis used the colonial courts to protect their property and sue white Saint Dominicans.[22]

The Code Noir sanctioned corporal punishment but had provisions intended to regulate the administration of punishments.

Some sugar planters, bent on earning high sugar yields, worked their slaves very hard. Costs to start a sugar cane plantation were very high, often causing the proprietor of the plantation to go into deep debt.[22] Despite a rural police, due to Saint-Domingue's rough terrain and isolation away from French administration, the Code Noir's protections were sometimes ignored on remote sugar plantations. Justin Girod-Chantrans, a famous contemporary French traveler and naturalist of the time noted one such sugar plantation:

"The slaves numbered roughly one hundred men and women of different ages, all engaged in digging ditches in a cane field, most of them naked or dressed in rags. The sun beat down on their heads; sweat ran from all parts of their bodies. Their arms and legs, worn out by excessive heat, by the weight of their picks and by the resistance of the clayey soil become so hardened that it broke their tools, the slaves nevertheless made tremendous efforts to overcome all obstacles. A dead silence reigned among them. In their faces, one could see the human suffering and pain they endured, but the time for rest had not yet come. The merciless eye of the plantation steward watched over the workers while several black commanders, dispersed among the workers and armed with long whips, delivered harsh blows to those who seemed too weary to sustain the pace and were forced to slow down. Men, women, young and old alike- none escaped the crack of the whip if they could not keep up pace."[27]

African culture remained strong among slaves to the end of French rule.The folk religion of Vodou commingled Catholic liturgy and ritual with the beliefs and practices of the Vodun religion of Guinea, Congo and Dahomey.[28] Saint Dominicans were hesitant to consider Vodou an authentic religion, perceiving it instead as superstition, and they promulgated laws against Vodou practices, effectively forcing it underground.[3]

Saint Dominican Creoles

_Cut.jpg.webp)

Saint-Domingue had the largest and wealthiest free population of color in the Caribbean; they were known as the gens de couleur (people of color). The royal census of 1789 counted roughly 65,000 mestizo.[29] While many of the gens de couleur were affranchis (ex-slaves), most members of this class were Creoles of color, i.e. free born blacks and mulattoes. As in New Orleans, a system of plaçage developed, in which white men had a kind of common-law marriage with slave or free mistresses, and provided for them with a dowry, sometimes freedom, and often education or apprenticeships for their children. Some such descendants of planters inherited considerable property.

While the French controlled Saint Domingue, they maintained a class system which covered both whites and free people of color. These classes divided up roles on the island and established a hierarchy. The highest class, known as the grands blancs (white noblemen), was composed of rich nobles, including royalty, and mainly lived in France. These individuals held most of the power and controlled much of the property on Saint-Domingue. Although their group was very small and exclusive, they were quite powerful.

Below the grands blancs were the petits blancs (white commoners) and the gens de couleur libres (free people of color). These classes inhabited Saint Domingue and held a lot of local political power and control of the militia. Petits blancs shared the same societal level as gens de couleur libres.

The gens de couleur libres class was made up of affranchis (ex-slaves), free-born blacks, and mixed-race people, and they controlled much wealth and land in the same way as petits blancs; they held full citizenship and civil equality with other French subjects.[22] Race was initially tied to culture and class, and some "white" Saint Dominicans had non-white ancestry.[21]

"These men are beginning to fill the colony... their numbers continually increasing amongst the whites, with fortunes often greater than those of the whites... Their strict frugality prompting them to place their profits in the bank every year, they accumulate huge capital sums and become arrogant because they are rich, and their arrogance increases in proportion to their wealth. They bid on properties that are for sale in every district and cause their prices to reach such astronomical heights that the whites who have not so much wealth are unable to buy, or else ruin themselves if they do persist. In this manner, in many districts the best land is owned by Creoles of color."[27]

Although the Creoles of color and affranchis held considerable power, they eventually became the subject of racism and a system of segregation due to the introduction of divisionist policies by the royal government, as the Bourbon regime feared the united power of the Saint Dominicans.

Starting in the early 1760s, and gaining much impetus after 1769, Bourbon royalist authorities began attempts to cut Saint Dominican Creoles of color out of Saint Dominican society, banning them from working in positions of public trust or as respected professionals. They were made subject to discriminatory colonial legislation. Statutes forbade gens de couleur from taking up certain professions, marrying whites, wearing European clothing, carrying swords or firearms in public, or attending social functions where whites were present.[23]

The regulations did not restrict their purchase of land, and many had already accumulated substantial holdings and became slaveowners. By 1789, they owned one-third of the plantation property and one-quarter of the slaves of Saint-Domingue.[23] Central to the rise of the gens de couleur planter class was the growing importance of coffee, which thrived on the marginal hillside plots to which they were often relegated. The largest concentration of gens de couleur was in the southern peninsula. This was the last region of the colony to be settled, owing to its distance from Atlantic shipping lanes and its formidable terrain, with the highest mountain range in the Caribbean. In the parish of Jérémie, the free population of color formed the majority of the population. Many lived in Port-au-Prince as well, which became an economic center in the South of the island.

White Indentured Servitude and Downturn of the Saint Dominican Economy

As the social systems of Saint Domingue began eroding after the 1760s, the plantation economy of Saint-Domingue also began weakening. The price of slaves doubled between 1750 and 1780; Saint Dominican land tripled in price during the same period. Sugar prices still increased, but at a much lower rate than before. The profitability of other crops like coffee collapsed in 1770, causing many planters to go into debt. The planters of Saint Domingue were eclipsed in their profits by enterprising businessmen; they no longer had a guarantee on their plantation investment, and the slave-trading economy came under increased scrutiny.[22]

Along with the establishment of a French abolitionist movement, the Société des amis des Noirs, French economists demonstrated that paid labor or indentured servitude were much more cost-effective than slave labor. In principle the widespread implementation of indentured servitude on plantations could have produced the same output as slave labor. However, the Bourbon King Louis XVI didn't want to change the labor system in his colonies, as slave labor was directly responsible for allowing France to surpass Britain in trade.[22]

Slaves, however, became expensive, each one costing around 300 Spanish dollars. To counteract expensive slave labor, white indentured servants were imported. White indentured servants usually worked for five to seven years and their masters provided them housing, food, and clothing.[30][31] Saint-Domingue gradually increased its reliance on indentured servants (known as petits blanchets or engagés) and by 1789 about 6 percent of all white Saint Dominicans were employed as labor on plantations along with slaves.[22]

Many of the indentured servants in Saint-Domingue were German settlers or Acadian refugees deported by the British from old Acadia during the French and Indian war.[32]

Despite signs of economic decline, Saint-Domingue continued to produce more sugar than all of the British Caribbean islands combined.[22]

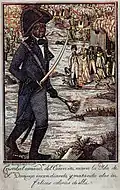

Marronnage

Thousands of slaves escaped into the mountains of Saint-Domingue, forming communities of maroons and raiding isolated plantations. The most famous was Mackandal, a one-armed slave, originally from the Guinea region of Africa, who escaped in 1751. A Vodou Houngan (priest), he united many of the different maroon bands. For the next six years, he staged successful raids while evading capture by the French. He and his followers reputedly killed more than 6,000 people. He preached a radical vision of killing the white population of Saint-Domingue. In 1758, after a failed plot to poison the drinking water of the planters, he was captured and burned alive at the public square in Cap-Français.

"The Minister should be informed that there are inaccessible or reputedly inaccesible areas in different sections of our colony which serve as retreat and shelter for maroons; it is in the mountains and in the forests that these tribes of slaves establish themselves and multiply, invading the plains from time to time, spreading alarm and always causing great damage to the inhabitants."[27]

Slaves who fled to remote mountainous areas were called marron (French) or mawon (Haitian Creole), meaning 'escaped slave'. The maroons formed close-knit communities that practised small-scale agriculture and hunting. They were known to return to plantations to free family members and friends. On a few occasions, they also joined the Taíno settlements, who had escaped the Spanish in the 17th century. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, there were a large number of maroons living in the Bahoruco mountains. In 1702, a French expedition against them killed three maroons and captured 11, but over 30 evaded capture, and retreated further into the mountainous forests. Further expeditions were carried out against them with limited success, though they did succeed in capturing one of their leaders, Michel, in 1719. In subsequent expeditions, in 1728 and 1733, French forces captured 46 and 32 maroons respectively. No matter how many detachments were sent against these maroons, they continued to attract runaways. Expeditions in 1740, 1742, 1746, 1757 and 1761 had minor successes against these maroons, but failed to destroy their hideaways.[33]

"They gather together in the woods and live there exempt from service to their masters without any other leader but one elected among them; others, under cover of the cane fields by day, wait at night to rob those who travel along the main roads, and go from plantation to plantation to steal farm animals to feed themselves, hiding in the living quarters of their friends who, ordinarily, participate in their thefts and who, aware of the goings on in the master's house, advise the fugitives so that they can take the necessary precautions to steal without getting caught."[27]

In 1776-7, a joint French-Spanish expedition ventured into the border regions of the Bahoruco mountains, with the intention of destroying the maroon settlements there. However, the maroons had been alerted of their coming, and had abandoned their villages and caves, retreating further into the mountainous forests where they could not be found. The detachment eventually returned, unsuccessful, and having lost many soldiers to illness and desertion. In the years that followed, the maroons attacked a number of settlements, including Fond-Parisien, for food, weapons, gunpowder and women. It was on one of these excursions that one of the maroon leaders, Kebinda, who had been born in freedom in the mountains, was captured. He later died in captivity.[34]

In 1782, de Saint-Larry decided to offer peace terms to one of the maroon leaders, Santiago, granted them freedom in return for which they would hunt all further runaways and return them to their owners. Eventually, at the end of 1785, terms were agreed, and the more than 100 maroons under Santiago's command stopped making incursions into French colonial territory.[35]

End of colonial rule

The Saint Dominican Rebellion (1791-1798)

.svg.png.webp)

In France, the majority of the Estates General, an advisory body to the King, reconstituted itself as the Republican National Assembly, made radical changes in French laws, and on 26 August 1789, published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, declaring all men free and equal. The French Revolution shaped the course of the conflict in Saint-Domingue and was at first widely welcomed on the island.

Wealthy Creole planters saw it as an opportunity to gain independence from France. The elite planters intended to take control of the island and create favorable trade regulations to further their own wealth and power and to restore social & political equality granted to Saint Dominican Creoles.[36]

Creole aristocrats like Vincent Ogé, Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, and the ex-governor of Saint-Domingue Guillaume de Bellecombe, incited several revolts to take control of Saint-Domingue from the Royal government. These revolts included the incitation of a slave revolt that destroyed much of the northern plain of Saint-Domingue. Saint Dominican rebel forces eventually defeated the Bourbon royalists, but they soon lost control of the slave revolt as Spanish and British forces concurrently invaded the colony.

"The rebellion was extremely violent ... the rich plain of the North was reduced to ruins and ashes ..."[37] Within two months, the slave revolt in northern Saint-Domingue killed 2,000 Saint Dominicans and burned 280 sugar plantations owned by grand blancs. Ash from blazing sugar cane fields fell from afar onto Cap-Français.[38] As the rebellion in Saint-Domingue dragged on, it changed in nature from a political revolution to a racial war.[21]

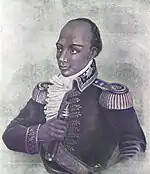

After months of arson and murder, Toussaint Louverture, a Saint Dominican plantation owner & Jacobin, and his general Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a field slave, took charge of the leaderless slave revolt; they formed an alliance with Spanish invasion forces. Louverture and Dessalines were inspired by the houngans (sorcerers or priests of Haitian Vodou) Dutty Boukman and François Mackandal.

As 7,000 French Republican forces arrived on the island in September 1792, they began fighting against the Saint Dominican Rebel, Bourbon Royalist, British, and Spanish forces. In an attempt to take control of the Saint Dominican slave revolt and entice Saint Dominican Creole rebels to join them, French Republicans declared amnesty for any revolting slaves and Creole rebels if they would fight for the Republic.

To gain amnesty, Louverture betrayed the Spanish forces, eradicated them, and joined the Republican revolutionary army.

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax from September 1792 to 1795 was the de facto ruler of Saint-Domingue. He was a French Girondist and abolitionist during the French Revolution, and closely associated with the Société des amis des Noirs (Friends of the Blacks Society).[39] His official title was Civil Commissioner. Within a year of his appointment, his powers were considerably expanded by the Committee of Public Safety.

Sonthonax believed that all of Saint-Domingue's whites were Bourbon royalist or rebel separatist conservatives attached to independence or joining Spain. He stripped away all of the military power of the white Saint Dominicans, and by doing so, he alienated them from the Republican government.[38] Here is some of Sonthonax's anti-white rhetoric aimed at radicalizing slaves to the Republican cause:

A vla yo donc yon foi démasqué cila la yo toi hélé zamis pays cila-la, qui livré la ville du Cap dans difé et dans pillage, zamis de france la yo qui gagné pour cri ralliement Vive le Roi, qui hélé Pagnols sur terre à nous, qui grossi zarmée à yo, qui livré yo postes que nous té confié yo, qui osé faire complots pour prend pays-ci baye Pagnols... cila yo qui fait complot là, c'est presque toute Blanc qui té à St Domingue, cila yo qui té gagné dettes en pile, quoique yo té gagné l'air riche, cila yo qui té vlé pillage parceque yo té pas gagné à rien.[40]

C'est cila io qui plus grands ennemis z'autres qui excité impatience z'autres, qui faire z'autres croire io va tromper z'autres, qui conseillé z'autres faire z'attroupements, & qui cherché faire z'autres soulevé. C'est quelques mauvais blancs & quelques femmes du 4 avril qui gagné peur perdi z'autres, & qui conseillé z'autres brûler cases, faire pillage, tuyé monde & faire brigandages. Io croire, parce que io va retarder révolution la, io va empêcher li caba. Io sottes! io pas voir io mêmes ta payé toute crimes io conseillé z'autres faire. Z'autres sages passé io, z'autres mérité la liberté passé io, z'autres commencé remplir devoirs citoyens, z'autres respecté la loi, l'ordre public & toutes autorités constituées la io... République France qui connoit la liberté & l'égalité assez pas capable vlé z'autres rêté toujours dans l'esclavage.[40]

Look here, once and for all unmasked, it's them who you call friends in this country, who delivered Cap-Français to fire and pillaging, those friends of France who have the rallying cry "Long live the King!", who called the Spanish to our land, who grew their army, who delivered them the posts that we entrusted to them, who have the audacity to plot to take this country and give it to the Spanish... those who are plotting, it's almost all of the whites who are in St. Domingue, those who had a bunch of debts, who seemed rich, it's them who wanted all of the pillaging because they don't have anything.

Those who are your biggest enemies, those who excited your impatience, who make you all believe that they'll fool you, who advised you to make regiments, and who sought to make you revolt. It's evil whites and women from April 4 who were afraid of losing you, and they advised you to burn homes, pillage, kill people and do banditry. They believe that, because these will delay the revolution, they will prevent it from finishing. They're idiots! They don't see that they will pay for all of the crimes they advised you all to make. You all are smarter than them, you deserve liberty more than them, you are beginning to fill the duties of citizens, you're respecting the law, public order and all of the constituted authorities... The French Republic who knows enough liberty and equality cannot allow you all to remain in slavery.

Many gens de couleur, the affranchis (ex-slaves) and Creole residents of the colony whose rights were restored by the French National Convention as part of the decree of 15 May 1792, asserted that they could form the military backbone of Republican Saint-Domingue; Sonthonax rejected this view as outdated in the wake of the August 1791 slave uprising. He believed that Saint-Domingue would need slave soldiers among the ranks of the colonial army if it was to survive. Sonthonax abolished slavery in Saint-Domingue with an emancipation proclamation; some of his critics allege that he ended slavery to maintain his own power.[38]

Louverture worked together with Sonthonax for a few years, but he ultimately forced Sonthonax out of his position in 1795, and became the sole ruler of northern Saint-Domingue.

The Saint Dominican Civil War and Invasion of Santo Domingo (1798-1801)

In 1799, Louverture started the Saint Dominican Civil War with Creole general André Rigaud who ruled an autonomous state in the south; Louverture claimed that Rigaud attempted to assassinate him. Louverture delegated most of the campaign to his lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who became infamous, during and after the civil war, for murdering about 10,000 Saint Dominican Creole captives and civilians.[41][42] After defeating Rigaud, Louverture became master of the whole French colony of Saint-Domingue.[43]

.svg.png.webp)

In November 1799, during the civil war in Saint-Domingue, Napoleon Bonaparte gained power in France. He created a new civil code; the French Civil Code of Napoleon affirmed the political and legal equality of all adult men; it established a merit-based society in which individuals advanced in education and employment because of talent rather than birth or social standing. The Civil Code confirmed many of the moderate revolutionary policies of the National Assembly but retracted measures passed by the more radical Convention.

Napoleon also passed a new constitution, declaring that the colonies would be subject to special laws.[44] Although slaves in Saint-Domingue suspected this meant the re-introduction of slavery, Napoleon began by confirming Louverture's position and promising to maintain the abolition.[45]

Napoleon forbade Louverture to control the formerly Spanish settlement on the eastern side of Hispaniola, as that would have given the Louverture a more powerful defensive position.[46] In January 1801, Louverture invaded the Spanish territory of Santo Domingo, taking possession of it from the governor, Don Garcia, with few difficulties. The area was less developed and populated than the French section. Louverture brought it under French law, abolishing slavery and embarking on a program of modernization. He now controlled the entire island.[47]

Louverture promulgated the Constitution of 1801 on 7 July, officially establishing his authority as governor general "for life" over the entire island of Hispaniola and confirming most of his existing policies. Article 3 of the constitution states: "There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French."[48]

During this time, Bonaparte met with Saint Dominican planters; they urged the restoration of slavery in Saint-Domingue, saying that it was integral to the colony's economy.[49]

Louverture as Saint-Domingue's Governor-General-for-life enacted forced plantation labor to prevent the collapse of the Saint Dominican economy. This may have contributed to a rebellion against his regime of forced labor led by his nephew and top general, Moïse, in October 1801. Louverture violently suppressed the labor rebellion, with the result that when the French ships arrived, not all of Saint-Domingue was automatically on Louverture's side.[50]

A minority of state officials and civil servants were exempt from manual labor, including Saint Dominican Creoles of color. Many poor Saint Dominicans had to work hard to survive, and they became increasingly motivated by their hunger. Consisting mostly of slaves, the population was uneducated and largely unskilled. They lived under Louverture's authoritarian control as forced rural laborers. White Saint Dominicans felt the sting of labor most sharply. While Louverture, an affranchi who had a tolerant master and later became a slave holder and plantation owner himself, felt magnanimity toward whites; Dessalines however, a former field slave, despised them.

Many of Saint-Domingue's whites fled the island during the Saint Dominican Civil War. Toussaint Louverture, however, understood that they formed a vital part of the Saint Dominican economy as a middle class, and in the hopes of slowing the impending economic collapse, he invited them to return. He gave property settlements and indemnities for war time losses, and promised equal treatment in his new Saint-Domingue; a good number of white Saint Dominican refugees did return. The refugees who came back to Saint-Domingue and believed in Toussaint Louverture's rule were later exterminated by Jean-Jacques Dessalines.[21]

The Haitian Revolution (1802-1804)

.svg.png.webp)

Napoleon dispatched troops in 1802 under the command of his brother-in-law, General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc, to restore French rule to the island.[51] Saint Dominican Creole leaders who were defeated during the Saint Dominican Civil War such as André Rigaud and Alexandre Pétion accompanied Leclerc's French expeditionary forces.[52]

Napoleon wanted to take control of Saint-Domingue again through diplomatic means. In late January 1802, Leclerc arrived and asked permission to land at Cap-Français, but Henri Christophe prevented him. At the same time, the Vicomte de Rochambeau suddenly attacked Fort-Liberté, effectively quashing the diplomatic option and starting a new war in Saint-Domingue.[53]

Both Louverture and Dessalines fought against the French expeditionary forces, but after the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot, Dessalines defected from his long-time ally Louverture and joined Leclerc's forces. Leclerc proclaimed peaceful intentions, but kept secret his orders to deport black officers holding a rank above captain.[54][55]

Eventually, a ceasefire was enacted between Louverture and the French expeditionary forces. During this ceasefire, Louverture was captured & arrested. Jean-Jacques Dessalines was at least partially responsible for Louverture's arrest, as asserted by several authors, including Louverture's son, Isaac. On 22 May 1802, after Dessalines learned that Louverture had failed to instruct a local rebel leader to lay down his arms per the recent ceasefire agreement, he immediately wrote to Leclerc to denounce Louverture's conduct as "extraordinary".[56]

Leclerc originally asked Dessalines to arrest Louverture, but he declined. Jean Baptiste Brunet was ordered to do so, and he deported Louverture and his aides to France, claiming that he suspected the former leader of plotting an uprising. Louverture warned, "In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep."[57][58]

For a few months, the island was quiet under Napoleonic rule. But when it became apparent that the French intended to re-establish slavery, because they had done so on Guadeloupe, Dessalines and Pétion switched sides again, in October 1802, and fought against the French. In November Leclerc died of yellow fever, like much of his army; the Vicomte de Rochambeau then became the commanding officer of French expeditionary forces.[59]

The Vicomte de Rochambeau fought a brutal campaign. His atrocities helped rally many former French loyalists to the Haitian rebel cause. A passage from the personal secretary of the later King of Northern Haiti (1811-1820), Henry I describes punishments some slaves received:

Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars? Have they not forced them to consume faeces? And, having flayed them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not thrown them into boiling cauldrons of cane syrup? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and poniard?[60]

Eventually, the British allied with the Haitian revolutionaries and enacted a naval blockade on the French forces. Dessalines led the Haitian revolution until its completion, when the French forces were finally defeated in 1803.[59] The last battle of the Haitian Revolution, the Battle of Vertières, occurred on 18 November 1803, near Cap-Haïtien. When the French withdrew, they had only 7,000 troops left to ship to France.

In 1804, all remaining whites in Saint-Domingue were slaughtered and massacred wholesale under the orders of Dessalines. Ex-slaves or Saint Dominican Creoles declared to be traitors to Dessalines' rule were also eradicated.

Genocide of the remaining whites in Saint-Domingue

Between February and April 1804, Governor-General-for-life Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered the genocide of all remaining whites in Haitian territory. He decreed that all those suspected of conspiring in the acts of the expeditionary army should be put to death, including Creoles of color and freed slaves deemed traitors to Dessalines' regime.[61][62] Dessalines gave the order to the cities of Haiti that all white people should also be put to death.[63] The weapons used should be silent weapons such as knives and bayonets rather than gunfire, so that the killing could be done more quietly, and avoid warning intended victims by the sound of gunfire and thereby giving them the opportunity to escape.[64]

From early January 1804 until 22 April 1804, squads of soldiers moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families.[65] Eyewitness accounts of the massacre describe imprisonment and killings even of whites who had been friendly and sympathetic to the Haitian Revolution.[66]

The course of the massacre showed an almost identical pattern in every city he visited. Before his arrival, there were only a few killings, despite his orders.[67] When Dessalines arrived, he demanded that his orders about mass killings of the area's white population should be put into effect. Reportedly, he ordered the unwilling to take part in the killings, especially men of mixed race, so that the blame should not be placed solely on the black population.[68][69] Mass killings took place on the streets and in places outside the cities.

In parallel to the killings, plundering and rape also occurred.[69] Women and children were generally killed last. White women were "often raped or pushed into forced marriages under threat of death."[69]

Dessalines did not specifically mention that the white women should be killed, and the soldiers were reportedly somewhat hesitant to do so. In the end, however, the women were also put to death, though normally at a later stage of the massacre than the adult males.[67] The argument for killing the women was that whites would not truly be eradicated if the white women were spared to give birth to new Frenchmen.[70]

Before his departure from a city, Dessalines would proclaim an amnesty for all the whites who had survived in hiding during the massacre. When these people left their hiding place however, they were murdered as well.[69] Some whites were, nevertheless, hidden and smuggled out to sea by foreigners.[69] There were notable exceptions to the ordered killings. A contingent of Polish defectors were given amnesty and granted Haitian citizenship for their renouncement of French allegiance and support of Haitian independence. Dessalines referred to the Poles as "the White Negroes of Europe", as an expression of his solidarity and gratitude.[71]

The Empire of Haiti (1804-1806)

Dessalines was crowned Emperor Jacques I of the Haitian Empire on 6 October 1804 in the city of Cap-Haïtien. On 20 May 1805, his government released the Imperial Constitution, naming Jean-Jacques Dessalines emperor for life with the right to name his successor. Dessalines declared Haiti to be an all-black nation and forbade whites from ever owning property or land there. The generals who served under Dessalines during the Haitian Revolution became the new planter class of Haiti.

In order to slow the economic collapse of Haiti, Dessalines enforced a harsh regimen of plantation labor on newly freed slaves. Dessalines demanded that all blacks work either as soldiers to defend the nation or return to the plantations as labourers, so as to raise commodity crops such as sugar and coffee for export to sustain his new empire. His forces were strict in enforcing this, to the extent that some black subjects felt they were enslaved again. Haitian society became feudal in nature as workers could not leave the land they worked.

Dessalines was assassinated on 17 October 1806 by rebels led by Haitian generals Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion; his body was found dismembered and mutilated.[72] Dessalines' murder did not solve the tensions in Haiti; instead, the country was torn into two new countries led by each general. The Northern State of Haiti (later the Kingdom of Haiti) maintained forced plantation labor and became rich, while the Southern Republic of Haiti abandoned forced plantation labor and collapsed economically.

Aftermath

The Haitian Revolution culminated in the elimination of slavery in Saint-Domingue and the founding of the Haitian Empire in the whole of Hispaniola. Having sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in April 1803, Napoleon lost interest in his failing ventures in the Western Hemisphere.

Between 1791 and 1810, more than 25,000 Saint Dominicans — planters, poorer whites ("petits blancs"), and free people of color ("gens de couleur libres"), as well as the slaves who accompanied them — fled primarily to the United States in 1793, Jamaica in 1798, and Cuba in 1803.[73] Many of them found their way to Louisiana, with the largest wave of refugees, more than 10,000 people — almost equally divided among whites, free people of color, and slaves — arriving in New Orleans between May 1809 and January 1810 after being expelled from Cuba,[74] nearly doubling the population of the city.[75] These refugees had a significant impact on the culture of Louisiana, including developing its sugar industry and cultural institutions.[76]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, American and British authors often referred to Saint-Domingue period as "Santo Domingo" or "San Domingo."[8]:2 This led to confusion with the earlier Spanish colony, and later the contemporary Spanish colony established at Santo Domingo during the colonial period; in particular, in political debates on slavery previous to the American Civil War, "San Domingo" was used to express fears of Southern whites of a slave rebellion breaking out in their own region. Today, the former Spanish possession contemporary with the early period of the French colony corresponds mostly with the Dominican Republic, whose capital is Santo Domingo. The name of Saint-Domingue was changed to Hayti (Haïti) when Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared the independence of all Hispaniola from the French in 1804.[77] Like the name Haiti itself, Saint-Domingue may refer to all of Hispaniola, or the western part in the French colonial period, while the Spanish version Hispaniola or Santo Domingo is often used to refer to the Spanish colonial period or the Dominican nation.

See also

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of Haiti

- List of colonial governors of Saint-Domingue

- Spanish Colony of Santo Domingo

Notes

- "Hispaniola Article". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Henson, Janine. "Dominican Republic 2014". CardioStart International. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- McAlister, Elizabeth (2012). "From Slave Revolt to a Blood Pact with Satan: The Evangelical Rewriting of Haitian History". Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. 41 (2): 187–215. doi:10.1177/0008429812441310. S2CID 145382199.

- "Dominican Republic – The first colony". Country Studies. Library of Congress; Federal Research Division. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- Columbus, Christopher (14 March 1493). "Epistola de Insulis Nuper Repertis" [Letter [to Lord Raphael Sanchez] About Recently Found Isles] (in Latin).

Quam protinus Hispanam dixi

- Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio (July–September 1954). "Acerca del Tratado de Ryswick" [About the Treaty of Ryswick]. Clío (in Spanish). 22 (100): 127–132.

- Von Grafenstein, Johanna (2005). Latin America and the Atlantic World (in English and Spanish). Cologne, Germany: Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. p. 352. ISBN 3-412-26705-8.

- Chartrand, René (1996). Napoleon's Overseas Army (3rd ed.). Hong Kong: Reed International Books Ltd. ISBN 0-85045-900-1.

- White, Ashli (2010). Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8018-9415-2.

- Burnard, Trevor; Garrigus, John (2016). The Plantation Machine: Atlantic Capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8122-9301-2.

- Bollet, A.J. (2004). Plagues and Poxes: The Impact of Human History on Epidemic Disease. New York, New York: Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 1-888799-79-X.

- James, C. L. R. (1963) [1938]. The Black Jacobins (2nd ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 45, 55. OCLC 362702.

- Herrmann, Molly M. (2005). The French Colonial Question and the Disintegration of While Supremacy in the Colony of Saint Domingue, 1789–1792 (PDF) (MA). p. 5.

- Coupeau, Steeve (2008). The History of Haiti. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 18–19, 23. ISBN 978-0-313-34089-5.

- Geggus, David Patrick (2009). "The Colony of Saint-Domingue on the Eve of Revolution". In Geggus, David Patrick; Fiering, Norman (eds.). The World of the Haitian Revolution. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-253-22017-2.

- Gayarré, Charles (1854). History of Louisiana: The French Domination. Vol. 1. New York, New York: Redfield. pp. 448–449.

- Herrmann 2005, p. 21.

- "Slavery in the Colonial Era". Africana Online. Archived from the original on 17 June 2006.

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives (October 2003). "The Transatlantic Slave Trade". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- Francis Byrne; John A. Holm (1993). Atlantic Meets Pacific: A Global View of Pidginization and Creolization; Elected Papers from the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics. United States of America: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 394.

- Carl A. Brasseaux, Glenn R. Conrad (1992). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees, 1792-1809. New Orleans: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana. pp. 9, 10, 11.

- Historic New Orleans Collection (2006). Common Routes: St. Domingue, Louisiana. New Orleans: The Collection. pp. 32, 33, 55, 56, 58.

- Hunt, Lynn; Censer, Jack, eds. (2001). "Slavery and the Haitian Revolution". Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. George Mason University and American Social History Project. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- Frostin, Charles (1962). "L'intervention britannique à Saint-Domingue en 1793" [British intervention in Saint-Domingue in 1793]. Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer (in French). 49 (176–177): 299. doi:10.3406/outre.1962.1358.

- Houdaille, Jacques (1973). "Quelques données sur la population de Saint-Domingue au XVIIIe siècle" [Some Data on the population of Saint-Domingue in the 18th Century]. Population (in French). 28 (4–5): 859–872. doi:10.2307/1531260. JSTOR 1531260.

- Arsenault, Natalie; Rose, Christopher (2006). "Africa Enslaved: A Curriculum Unit on Comparative Slave Systems for Grades 9-12" (PDF). University of Texas at Austin. p. 57. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- Carolyn E. Fick (1990). The Making of Haiti, The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below. The University of Tennesse Press. pp. 19, 28, 51, 52.

- Vodou is a Dahomean word meaning 'god' or 'spirit'.

- Frostin 1962, pp. 293–365.

- Melton McLaurin, Michael Thomason (1981). Mobile the life and times of a great Southern city (1st ed.). United States of America: Windsor Publications. p. 19.

- "Atlantic Indentured Servitude". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- Christopher Hodson (Spring 2007). ""A bondage so harsh": Acadian labor in the French Caribbean, 1763-1766". Early American Studies. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Moreau de Saint-Mery, The Border Maroons of Saint Domingue, in "Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas", ed. by Richard Price (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 135-6.

- Moreau de Saint-Mery, The Border Maroons of Saint Domingue, in "Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas", ed. by Richard Price (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 136-8.

- Moreau de Saint-Mery, The Border Maroons of Saint Domingue, in "Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas", ed. by Richard Price (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 139-142.

- Weil, Thomas E.; Knippers Black, Jan; Blustein, Howard I.; Johnston, Kathryn T.; McMorris, David S.; Munson, Frederick P. (1985). Haiti: A Country Study. Foreign Area Handbook Series. Washington, D.C.: The American University.

- Edwards 1797, p. 68.

- Rogozinski, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 167–168. ISBN 0-8160-3811-2.

- Stein, Robert (1985). Leger Felicite Sonthonax: The Lost Sentinel of the Republic. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-3218-1.

- Marie-Christine Hazaël-Massieux (2008). Textes anciens en créole français de la Caraïbe: Histoire et analyse. Editions Publibook. pp. 189, 197, 208. ISBN 978-2-7483-7356-1.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 179–80.

- James 1963, pp. 236–237.

- Bell 2007, pp. 177, 189–191.

- Bell 2007, p. 180.

- Bell 2007, p. 184.

- Bell 2007, p. 186.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 189–91.

- Ogé, Jean-Louis (2002). Toussaint Louverture et l'Indépendence d'Haïti [Toussaint Louverture and the Independence of Haiti] (in French). Brossard, Québec: Les Éditions pour Tous. p. 140. ISBN 2-922086-26-7.

- Bell 2007, pp. 217–22.

- Bell 2007, pp. 206–209, 226–229, 250.

- James, pp. 292–94; Bell, pp. 223–24

- Fenton, Louise, Pétion, Alexander Sabès (1770-1818) in Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of slave resistance and rebellion. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. p374-375

- Bell 2007, pp. 232–234.

- James 1963, pp. 292–294.

- Bell 2007, pp. 223–224.

- Girard, Philippe R. (July 2012). "Jean-Jacques Dessalines and the Atlantic System: A Reappraisal" (PDF). The William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 69 (3): 559. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.69.3.0549. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

a list of “extraordinary expenses incurred by General Brunet in regards to [the arrest of] Toussaint” started with “gifts in wine and liquor, gifts to Dessalines and his spouse, money to his officers: 4000 francs.”

- Abbott, Elizabeth (1988). Haiti: An Insider's History of the Rise and Fall of the Duvaliers. Simon & Schuster. p. viii ISBN 0-671-68620-8

- Girard, Philippe R. (2011), The Slaves who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804, University of Alabama Press

- "The Slave Rebellion of 1791". Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- Heinl, Robert Debs; Heinl, Nancy Gordon; Heinl, Michael (2005) [1996]. Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492–1995 (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-3177-0. OCLC 255618073.

- St. John, Spenser (1884). "Hayti or The Black Republic". p. 75. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Philippe R. Girard (2011). The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence 1801–1804. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1732-4|pages 319-322

- Girard 2011, pp. 319–322.

- Dayan 1998, p. 4.

- Danner, Mark (2011). Stripping Bare the Body. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4587-6290-0.

- Jeremy D. Popkin (15 February 2010). Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection. University of Chicago Press. pp. 363–364. ISBN 978-0-226-67585-5. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- Girard 2011, pp. 321–322.

- Dayan 1998, p. .

- Girard 2011, p. 321.

- Girard 2011, p. 322.

- Susan Buck-Morss (2009). Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-8229-7334-8.

- "Slave Revolt in St. Domingue". Fsmitha.com.

- Lachance, Paul F. (1988). "The 1809 Immigration of Saint-Domingue Refugees to New Orleans: Reception, Integration and Impact". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 29 (2): 110. JSTOR 4232650.

- Lachance 1988, pp. 110–111.

- Lachance 1988, p. 112.

- Brasseaux, Carl A.; Conrad, Glenn R., eds. (2016). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees 1792-1809. Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. ISBN 978-1-935754-60-2.

- "A Brief History of Dessalines from 1825 Missionary Journal". webster.edu. VOL. VI, NO. 10. October 1825. pp. 292–297. Archived from the original on 28 December 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

References

- Bell, Madison Smartt (2007). Toussaint Louverture: A Biography. New York, New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42337-6.

- Butel, Paul (2002). Histoire des Antilles françaises: XVIIe-XXe siècle [For History]. Collection "Pour l'histoire" (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-01540-6. OCLC 301674023.

- Garrigus, John (2002). Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in Saint-Domingue. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. ISBN 0-230-10837-7. OCLC 690382111.

Further reading

- Savary des Brûlons, Jacques (1748). "Saint Domingue". Dictionnaire universel de commerce (in French). Paris: Estienne et fils. hdl:2027/ucm.5317968141.

- Koekkoek, René (2020). The Citizenship Experiment Contesting the Limits of Civic Equality and Participation in the Age of Revolutions (PDF). Studies in the History of Political Thought. Lieden, Netherlands: Brill.

Saint-Domingue (Haiti).

External links

- The Louverture Project: Saint-Domingue – Saint-Domingue page on Haitian history Wiki.

- The Louverture Project: Slavery in Saint-Domingue