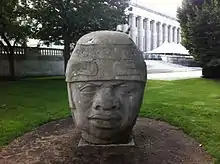

Olmec colossal heads

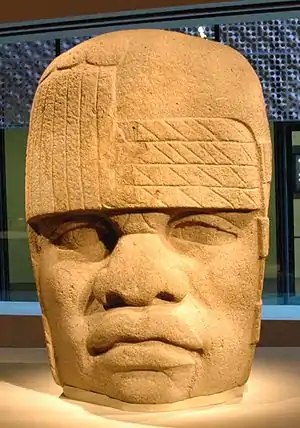

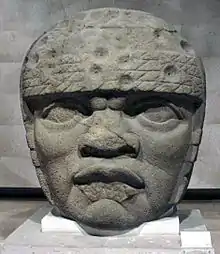

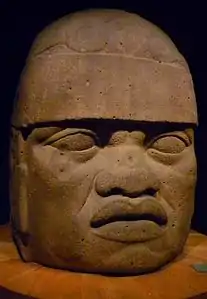

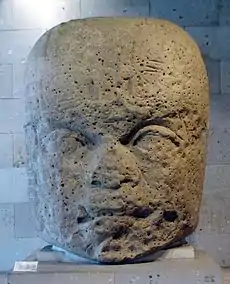

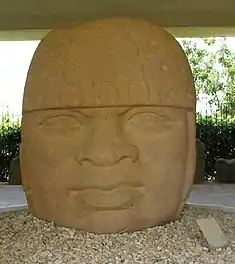

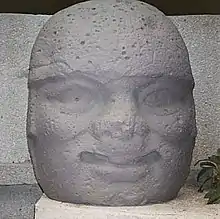

The Olmec colossal heads are stone representations of human heads sculpted from large basalt boulders. They range in height from 1.17 to 3.4 metres (3.8 to 11.2 ft). The heads date from at least 900 BC and are a distinctive feature of the Olmec civilization of ancient Mesoamerica.[1] All portray mature individuals with fleshy cheeks, flat noses, and slightly-crossed eyes; their physical characteristics correspond to a type that is still common among the inhabitants of Tabasco and Veracruz. The backs of the monuments often are flat. The boulders were brought from the Sierra de Los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz. Given that the extremely large slabs of stone used in their production were transported over large distances (over 150 kilometres (93 mi)), requiring a great deal of human effort and resources, it is thought that the monuments represent portraits of powerful individual Olmec rulers. Each of the known examples has a distinctive headdress. The heads were variously arranged in lines or groups at major Olmec centres, but the method and logistics used to transport the stone to these sites remain unclear. They all display distinctive headgear and one theory is that these were worn as protective helmets, maybe worn for war or to take part in a ceremonial Mesoamerican ballgame.

The discovery of the first colossal head at Tres Zapotes in 1862 by José María Melgar y Serrano was not well documented nor reported outside of Mexico.[2] The excavation of the same colossal head by Matthew Stirling in 1938 spurred the first archaeological investigations of Olmec culture. Seventeen confirmed examples are known from four sites within the Olmec heartland on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Most colossal heads were sculpted from spherical boulders but two from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán were re-carved from massive stone thrones. An additional monument, at Takalik Abaj in Guatemala, is a throne that may have been carved from a colossal head. This is the only known example from outside the Olmec heartland.

Dating the monuments remains difficult because of the movement of many from their original contexts prior to archaeological investigation. Most have been dated to the Early Preclassic period (1500–1000 BC) with some to the Middle Preclassic (1000–400 BC) period. The smallest weigh 6 tons, while the largest is variously estimated to weigh 40 to 50 tons, although it was abandoned and left uncompleted close to the source of its stone.

Olmec civilization

The Olmec civilization developed in the lowlands of southeastern Mexico between 1500 and 400 BC.[3] The Olmec heartland lies on the Gulf Coast of Mexico within the states of Veracruz and Tabasco, an area measuring approximately 275 kilometres (171 mi) east to west and extending about 100 kilometres (62 mi) inland from the coast.[4] The Olmecs are regarded as the first civilization to develop in Mesoamerica and the Olmec heartland is one of six cradles of civilization worldwide, the others being the Norte Chico culture of South America, the Erlitou culture of China's Yellow River, the Indus Valley civilization of the Indian subcontinent, the civilization of ancient Egypt in Africa, and the Sumerian civilization of ancient Iraq. Of these, only the Olmec civilization developed in a lowland tropical forest setting.[3]

The Olmecs were one of the first inhabitants of the Americas to construct monumental architecture and to settle in towns and cities, predated only by the Caral civilization. They were also the first people in the Americas to develop a sophisticated style of stone sculpture.[3] In the first decade of the 21st century, evidence emerged of Olmec writing, with the earliest examples of Olmec hieroglyphs dating to around 650 BC. Examples of script have been found on roller stamps and stone artifacts; the texts are short and have been partially deciphered based on their similarity to other Mesoamerican scripts.[5] The evidence of complex society developing in the Olmec heartland has led to the Olmecs being regarded as the "Mother Culture" of Mesoamerica,[3] although this concept remains controversial.[6]

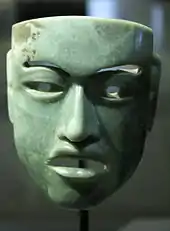

Some of the Olmecs' rulers seem to have served religious functions. The city of San Lorenzo was succeeded as the main centre of the civilization by La Venta in about 900 BC, with Tres Zapotes and Laguna de los Cerros possibly sharing the role; other urban centres were much less significant. The nature and degree of the control exercised by the centres over a widespread rural population remains unclear.[7] Very fine Olmec art, much clearly made for an elite,[8] survives in several forms, notably Olmec figurines, and larger sculptures such as The Wrestler. The figurines have been recovered in large numbers and are mostly in pottery; these were presumably widely available to the population. Together with these, of particular relevance to the colossal heads are the "Olmec-style masks" in stone,[9] so called because none have yet been excavated in circumstances that allow the proper archaeological identification of an Olmec context. These evocative stone face masks present both similarities and differences to the colossal heads. Two thirds of Olmec monumental sculpture represents the human form, and the colossal heads fall within this major theme of Olmec art.[10]

Dating

The colossal heads cannot be precisely dated. However, the San Lorenzo heads were buried by 900 BC, indicating that their period of manufacture and use was earlier still. The heads from Tres Zapotes had been moved from their original context before they were investigated by archaeologists and the heads from La Venta were found partially exposed on the modern ground surface. The period of production of the colossal heads is therefore unknown, as is whether it spanned a century or a millennium.[11] Estimates of the time span during which colossal heads were produced vary from 50 to 200 years.[12] The San Lorenzo heads are believed to be the oldest, and are the most skillfully executed.[13] All of the stone heads have been assigned to the Preclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology, generally to the Early Preclassic (1500–1000 BC), although the two Tres Zapotes heads and the La Cobata Head are attributed to the Middle Preclassic (1000–400 BC).[14]

Characteristics

Olmec colossal heads vary in height from 1.47 to 3.4 metres (4.8 to 11.2 ft) and weigh between 6 and 50 tons.[15] All of the Olmec colossal heads depict mature men with flat noses and fleshy cheeks; the eyes tend to be slightly crossed. The general physical characteristics of the heads are of a type that is still common among people in the Olmec region in modern times. The backs of the heads are often flat, as if the monuments were originally placed against a wall.[1] All examples of Olmec colossal heads wear distinctive headdresses that probably represent cloth or animal hide originals.[16] Some examples have a tied knot at the back of the head, and some are decorated with feathers. A head from La Venta is decorated with the head of a bird. There are similarities between the headdresses on some of the heads that has led to speculation that specific headdresses may represent different dynasties, or perhaps identify specific rulers. Most of the heads wear large earspools inserted into the ear lobes.[11]

All of the heads are realistic, unidealised and frank descriptions of the men. It is likely that they were portraits of living (or recently deceased) rulers well known to the sculptors.[11] Each head is distinct and naturalistic, displaying individualised features.[13] They were once thought to represent ballplayers although this theory is no longer widely held; it is possible, however, that they represent rulers equipped for the Mesoamerican ballgame.[11] Facial expressions depicted on the heads vary from stern through placid to smiling.[15] The most naturalistic Olmec art is the earliest, appearing suddenly without surviving antecedents, with a tendency towards more stylised sculpture as time progressed.[17] Some surviving examples of wooden sculpture recovered from El Manatí demonstrate that the Olmecs are likely to have created many more perishable sculptures than works sculpted from stone.[18]

In the late nineteenth century, José Melgar y Serrano described a colossal head as having "Ethiopian" features and speculations that the Olmec had African origins resurfaced in 1960 in the work of Alfonso Medellín Zenil and in the 1970s in the writings of Ivan van Sertima.[19] Such speculation is not taken seriously by Mesoamerican scholars such as Richard Diehl and Ann Cyphers.[20] Genetic studies have shown that, rather than Africa, the earliest Americans had ancestry closer to Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians.[21]

Although all the colossal heads are broadly similar, there are distinct stylistic differences in their execution.[13] One of the heads from San Lorenzo bears traces of plaster and red paint, suggesting that the heads were originally brightly decorated.[11] Heads did not just represent individual Olmec rulers; they also incorporated the very concept of rulership itself.[22]

Manufacture

The production of each colossal head must have been carefully planned, given the effort required to ensure the necessary resources were available; it seems likely that only the more powerful Olmec rulers were able to mobilise such resources. The workforce would have included sculptors, labourers, overseers, boatmen, woodworkers and other artisans producing the tools to make and move the monument, in addition to the support needed to feed and otherwise attend to these workers. The seasonal and agricultural cycles and river levels needed to have been taken into account to plan the production of the monument and the whole project may well have taken years from beginning to end.[23]

Archaeological investigation of Olmec basalt workshops suggest that the colossal heads were first roughly shaped using direct percussion to chip away both large and small flakes of stone. The sculpture was then refined by retouching the surface using hammerstones, which were generally rounded cobbles that could be of the same basalt as the monument itself, although this was not always the case. Abrasives were found in association with workshops at San Lorenzo, indicating their use in the finishing of fine detail. Olmec colossal heads were fashioned as in-the-round monuments with varying levels of relief on the same work; they tended to feature higher relief on the face and lower relief on the earspools and headdresses.[24] Monument 20 at San Lorenzo is an extensively damaged throne with a figure emerging from a niche. Its sides were broken away and it was dragged to another location before being abandoned. It is possible that this damage was caused by the initial stages of re-carving the monument into a colossal head but that the work was never completed.[25]

All seventeen of the confirmed heads in the Olmec heartland were sculpted from basalt mined in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz.[26] Most were formed from coarse-grained, dark-grey basalt known as Cerro Cintepec basalt after a volcano in the range. Investigators have proposed that large Cerro Cintepec basalt boulders found on the southeastern slopes of the mountains are the source of the stone for the monuments.[27] These boulders are found in an area affected by large lahars (volcanic mudslides) that carried substantial blocks of stone down the mountain slopes, which suggests that the Olmecs did not need to quarry the raw material for sculpting the heads.[28] Roughly spherical boulders were carefully selected to mimic the shape of a human head.[29] The stone for the San Lorenzo and La Venta heads was transported a considerable distance from the source. The La Cobata head was found on El Vigia hill in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas and the stone from Tres Zapotes Colossal Head 1 and Nestepe Colossal Head 1 (also known as Tres Zapotes Monuments A and Q) came from the same hill.[26]

The boulders were transported over 150 kilometres (93 mi) from the source of the stone.[30] The exact method of transportation of such large masses of rock are unknown, especially since the Olmecs lacked beasts of burden and functional wheels,[31] and they were likely to have used water transport whenever possible.[26] Coastal currents of the Gulf of Mexico and in river estuaries might have made the waterborne transport of monuments weighing 20 tons or more impractical.[32] Two badly damaged Olmec sculptures depict rectangular stone blocks bound with ropes. A largely destroyed human figure rides upon each block, with their legs hanging over the side. These sculptures may well depict Olmec rulers overseeing the transport of the stone that would be fashioned into their monuments.[31] When transport over land was necessary, the Olmecs are likely to have used causeways, ramps and roads to facilitate moving the heads.[33] The regional terrain offers significant obstacles such as swamps and floodplains; avoiding these would have necessitated crossing undulating hill country. The construction of temporary causeways using the suitable and plentiful floodplain soils would have allowed a direct route across the floodplains to the San Lorenzo Plateau. Earth structures such as mounds, platforms and causeways upon the plateau demonstrate that the Olmec possessed the necessary knowledge and could commit the resources to build large-scale earthworks.[34]

The flat backs of many of the colossal heads represented the flat bases of the monumental thrones from which they were reworked. Only four of the seventeen heartland heads do not have flattened backs, indicating the possibility that the majority were reworked monuments. Alternatively, the backs of many of these massive monuments may have been flattened to ease their transport,[35] providing a stable form for hauling the monuments with ropes.[36] Two heads from San Lorenzo have traces of niches that are characteristic of monumental Olmec thrones and so were definitely reworked from earlier monuments.[35]

| Site name | Location | Monument | Alternative name | Height | Width | Depth | Weight (tons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 1 | Monument 1 | 2.84 metres (9.3 ft) | 2.11 metres (6.9 ft) | 25.3 | |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 2 | Monument 2 | 2.69 metres (8.8 ft) | 1.83 metres (6.0 ft) | 1.05 metres (3.4 ft) | 20 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 3 | Monument 3 | 1.78 metres (5.8 ft) | 1.63 metres (5.3 ft) | 0.95 metres (3.1 ft) | 9.4 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 4 | Monument 4 | 1.78 metres (5.8 ft) | 1.17 metres (3.8 ft) | 0.95 metres (3.1 ft) | 6 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 5 | Monument 5 | 1.86 metres (6.1 ft) | 1.47 metres (4.8 ft) | 1.15 metres (3.8 ft) | 11.6 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 6 | Monument 17 | 1.67 metres (5.5 ft) | 1.41 metres (4.6 ft) | 1.26 metres (4.1 ft) | 8–10 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 7 | Monument 53 | 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) | 1.85 metres (6.1 ft) | 1.35 metres (4.4 ft) | 18 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 8 | Monument 61 | 2.2 metres (7.2 ft) | 1.65 metres (5.4 ft) | 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) | 13 |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 9 | Monument 66 | 1.65 metres (5.4 ft) | 1.36 metres (4.5 ft) | 1.17 metres (3.8 ft) | |

| San Lorenzo | Veracruz | Colossal Head 10 | Monument 89 | 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) | 1.43 metres (4.7 ft) | 0.92 metres (3.0 ft) | 8 |

| La Venta | Tabasco | Monument 1 | 2.41 metres (7.9 ft) | 2.08 metres (6.8 ft) | 1.95 metres (6.4 ft) | 24 | |

| La Venta | Tabasco | Monument 2 | 1.63 metres (5.3 ft) | 1.35 metres (4.4 ft) | 0.98 metres (3.2 ft) | 11.8 | |

| La Venta | Tabasco | Monument 3 | 1.98 metres (6.5 ft) | 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) | 1 metre (3.3 ft) | 12.8 | |

| La Venta | Tabasco | Monument 4 | 2.26 metres (7.4 ft) | 1.98 metres (6.5 ft) | 1.86 metres (6.1 ft) | 19.8 | |

| Tres Zapotes | Veracruz | Monument A | Colossal Head 1 | 1.47 metres (4.8 ft) | 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) | 1.45 metres (4.8 ft) | 7.8 |

| Tres Zapotes | Veracruz | Monument Q | Colossal Head 2, Nestape Head | 1.45 metres (4.8 ft) | 1.34 metres (4.4 ft) | 1.26 metres (4.1 ft) | 8.5 |

| La Cobata | Veracruz | La Cobata Head | 3.4 metres (11 ft) | 3 metres (9.8 ft) | 3 metres (9.8 ft) | 40 | |

| Takalik Abaj | Retalhuleu | Monument 23 | 1.84 metres (6.0 ft) | 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) | 1.56 metres (5.1 ft) |

Known monuments

Seventeen confirmed examples are known.[1] An additional monument, at Takalik Abaj in Guatemala, is a throne that may have been carved from a colossal head.[38] This is the only known example outside of the Olmec heartland on the Gulf Coast of Mexico.[39] Possible fragments of additional colossal heads have been recovered at San Lorenzo and at San Fernando in Tabasco.[33] Crude colossal stone heads are also known in the Southern Maya area where they are associated with the potbelly style of sculpture.[40] Although some arguments have been made that they are pre-Olmec, these latter monuments are generally believed to be influenced by the Olmec style of sculpture.[41]

| Site | No. of monuments[1] |

|---|---|

| San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán | 10 |

| La Venta | 4 |

| Tres Zapotes | 2 |

| La Cobata | 1 |

| Takalik Abaj | 1 (possible)[42] |

San Lorenzo

The ten colossal heads from San Lorenzo originally formed two roughly parallel lines running north-south across the site.[43] Although some were recovered from ravines,[44] they were found close to their original placements and had been buried by local erosion. These heads, together with a number of monumental stone thrones, probably formed a processional route across the site, powerfully displaying its dynastic history.[45] Two of the San Lorenzo heads had been re-carved from older thrones.[46]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 1 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 1)[47] was lying facing upwards when excavated. The erosion of a path passing on top of the monument uncovered its eye and led to the discovery of the Olmec site.[48] Colossal Head 1 is 2.84 metres (9.3 ft) high;[49] it measures 2.11 metres (6.9 ft) wide and it weighs 25.3 tons. The monument was discovered partially buried at the edge of a gully by Matthew Stirling in 1945. When discovered, it was lying on its back, looking upwards. It was associated with a large number of broken ceramic vessels and figurines.[50] The majority of these ceramic remains have been dated to between 800 and 400 BC;[51] some pieces have been dated to the Villa Alta phase (Late Classic period, 800–1000 AD).[52] The headdress possesses a plain band that is tied at the back of the head. The upper portion of the headdress is decorated with a U-shaped motif.[53] This element descends across the front of the headdress, terminating on the forehead. On the front portion it is decorated with five semicircular motifs.[54] The scalp piece does not meet the horizontal band, leaving a space between the two pieces. On each side of the face a strap descends from the headdress and passes in front of the ear.[53] The forehead is wrinkled in a frown. The lips are slightly parted without revealing the teeth. The cheeks are pronounced and the ears are particularly well executed.[55] The face is slightly asymmetric, which may be due to error on the part of the sculptors or may accurately reflect the physical features of the portrait's subject.[56] The head has been moved to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa ("Anthropological Museum of Xalapa").[50]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 2 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 2)[47] was reworked from a monumental throne.[35] The head stands 2.69 metres (8.8 ft) high and measures 1.83 metres (6.0 ft) wide by 1.05 metres (3.4 ft) deep; it weighs 20 tons. Colossal Head 2 was discovered in 1945 when Matthew Stirling's guide cleared away some of the vegetation and mud that covered it.[57] The monument was found lying on its back, facing the sky, and was excavated in 1946 by Stirling and Philip Drucker. In 1962 the monument was removed from the San Lorenzo plateau in order to put it on display as part of "The Olmec tradition" exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston in 1963.[58] San Lorenzo Colossal Head 2 is currently in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.[59] The head was associated with a number of ceramic finds; they have been dated to the Early Preclassic and Late Classic periods.[60] Colossal Head 2 wears a complex headdress that sports a horizontal band tied at the back of the head; this is decorated with three bird's heads that are located above the forehead and temples.[61] The scalp piece is formed from six strips running towards the back of the head. The front of the headdress above the horizontal band is plain. Two short straps hang down from the headdress in front of the ears. The ear jewellery is formed by large squared hoops or framed discs. The left and right ornaments are different, with radial lines on the left earflare, a feature absent on the right earflare.[62] The head is badly damaged due to an unfinished reworking process.[63] This process has pitmarked the entire face with at least 60 smaller hollows and 2 larger holes.[64] The surviving features appear to depict an ageing man with the forehead creased into a frown. The lips are thick and slightly parted to reveal the teeth; the head has a pronounced chin.[63]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 3 is also known as San Lorenzo Monument 3.[47] The head measures 1.78 metres (5.8 ft) high by 1.63 metres (5.3 ft) wide by 0.95 metres (3.1 ft) deep and weighs 9.4 tons. The head was discovered in a deep gully by Matthew Stirling in 1946; it was found lying face down and its excavation was difficult due to the wet conditions in the gully.[65] The monument was found 0.8 kilometres (0.50 mi) southwest of the main mound at San Lorenzo, however, its original location is unknown; erosion of the gully may have resulted in significant movement of the sculpture.[66] Head 3 has been moved to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa.[65] The headdress is complex, with the horizontal basal band being formed by four horizontal cords, with diagonal folds above each eye. A small skullcap tops the headdress. A large flap formed of four cords drops down both sides of the head, completely covering the ears.[67] The face has a typically frowning brow and, unusually, has clearly defined eyelids. The lips are thick and slightly parted; the front of the lower lip has broken away completely,[68] and the lower front of the headdress is pitted with 27 irregularly spaced artificial depressions.[69]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 4 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 4)[47] weighs 6 tons[70] and has been moved to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa.[71] Colossal Head 4 is 1.78 metres (5.8 ft) high,[72] 1.17 metres (3.8 ft) wide and 0.95 metres (3.1 ft) deep.[69] The head was discovered by Matthew Stirling in 1946, 550 metres (600 yd) northwest of the principal mound, at the edge of a gully. When excavated, it was found to be lying on its right-hand side and in a very good state of preservation.[69] Ceramic materials excavated with the head became mixed with ceramics associated with Head 5, making ceramic dating of the monument difficult. The headdress is decorated with a horizontal band formed of four sculpted cords, similar to those of Head 3. On the right-hand side, three tassels descend from the upper portion of the headdress; they terminate in a total of eight strips that hang down across the horizontal band. These tassels are judged to represent hair rather than cords.[73] Also on the right hand side, two cords descend across the ear and continue to the base of the monument.[74] On the left-hand side, three vertical cords descend across the ear. The earflare is only visible on the right hand side; it is formed of a plain disc and peg. The face is that of an ageing man with a creased forehead, low cheekbones and a prominent chin. The lips are thick and slightly parted.[75]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 5 is also known as San Lorenzo Monument 5.[47] The monument stands 1.86 metres (6.1 ft) high and measures 1.47 metres (4.8 ft) wide by 1.15 metres (3.8 ft) deep. It weighs 11.6 tons. The head was discovered by Matthew Stirling in 1946, face down in a gully to the south of the principal mound.[76] The head is particularly well executed and is likely to have been found close to its original location. Ceramics recovered during its excavation became mixed with those from the excavation of Head 4.[77] The mixed ceramics have been dated to the San Lorenzo and Villa Alta phases (approximately 1400–1000 BC and 800–1000 AD respectively).[78] Colossal Head 5 is particularly well preserved,[79] although the back of the headdress band was damaged when the head was moved from the archaeological site.[80] The band of the headdress is set at an angle and has a notch above the bridge of the nose.[77] The headdress is decorated with jaguar paws;[81] this general identification of the decoration is contested by Beatriz de la Fuente since the "paws" have three claws each; she identifies them as the claws of a bird of prey. At the back of the head, ten interlaced strips form a net decorated with disc motifs. Two short straps descend from the headdress in front of the ears. The ears are adorned with disc-shaped earspools with pegs. The face is that of an ageing man with wrinkles under the eyes and across the bridge of the nose, and a forehead that is creased in a frown.[82] The lips are slightly parted.[83] Colossal Head 5 has been moved to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa.[76]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 6 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 17)[47] is one of the smaller examples of colossal heads, standing 1.67 metres (5.5 ft).[72] It measures 1.41 metres (4.6 ft) wide by 1.26 metres (4.1 ft) deep and is estimated to weigh between 8 and 10 tons. The head was discovered by a local farmworker and was excavated in 1965 by Luis Aveleyra and Román Piña Chan. The head had collapsed into a ravine under its own weight and was found face down on its left hand side. In 1970 it was transported to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for the museum's centenary exhibition. After its return to Mexico, it was placed in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.[80] It is sculpted with a net-like head covering joined together with sculpted beads.[84] A covering descends from under the headdress to cover the back half of the neck.[85] The headband is divided into four strips and begins above the right ear, extending around the entire head. A short strap descends from either side of the head to the ear. The ear ornaments are complex and are larger at the front of the ear than at the back. The face is that of an ageing male with the forehead creased in a frown, wrinkles under the eyes, sagging cheeks and deep creases on either side of the nose. The face is somewhat asymmetric, possibly due to errors in the execution of the monument.[86]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 7 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 53)[47] measures 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) high by 1.85 metres (6.1 ft) wide by 1.35 metres (4.4 ft) deep and weighs 18 tons.[87] San Lorenzo Colossal Head 7 was reworked from a monumental throne;[35] it was discovered by a joint archaeological project by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and Yale University, as a result of a magnetometer survey. It was buried at a depth of less than 1 metre (3.3 ft) and was lying facing upwards,[88] leaning slightly northwards on its right hand side.[89] The head is poorly preserved and has suffered both from erosion and deliberate damage.[89] The headdress is decorated with a pair of human hands;[88] a feathered ornament is carved at the back of the headband and two discs adorn the front.[90] A short strap descends from the headband and hangs in front of the right ear. The head sports large earflares that completely cover the earlobes, although severe erosion makes their exact form difficult to distinguish. The face has wrinkles between the nose and cheeks, sagging cheeks and deep-set eyes; the lips are badly damaged and the mouth is open, displaying the teeth.[91] In 1986 the head was transported to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa.[92]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 8 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 61) stands 2.2 metres (7.2 ft) high;[93] it measures 1.65 metres (5.4 ft) wide by 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) deep and weighs 13 tons.[94] It is one of the finest examples of an Olmec colossal head. It was found lying on its side to the south of a monumental throne.[95] The monument was discovered at a depth of 5 metres (16 ft) during a magnetometer survey of the site in 1968;[96] it has been dated to the Early Preclassic.[93] After discovery it was initially reburied;[97] it was moved to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa in 1986.[98] The headdress is decorated with the talons or claws of either a jaguar or an eagle.[95] It has a headband and a cover that descends from under the headdress proper behind the ears.[99] Two short straps descend in front of the ears.[100] The head sports large ear ornaments in the form of pegs. The face is that of a mature male with sagging cheeks and wrinkles between these and the nose. The forehead is gathered in a frown. The mouth is slightly parted to reveal the teeth.[101] Most of the head is carved in a realistic manner, the exception being the ears. These are stylised and represented by one question mark shape contained within another. The head is very well preserved and displays a fine finish.[102]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 9 is also known as San Lorenzo Monument 66.[47] It measures 1.65 metres (5.4 ft) high by 1.36 metres (4.5 ft) wide by 1.17 metres (3.8 ft) deep. The head was exposed in 1982 by erosion of the gullies at San Lorenzo;[102] it was found leaning slightly on its right hand side and facing upwards, half covered by the collapsed side of a gully and washed by a stream. Although it was documented by archaeologists, it remained for some time in its place of discovery before being moved to the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa. The headdress is of a single piece without a distinct headband. The sides display features that are possibly intended to represent long hair trailing to the bottom of the monument.[103] The earflares are rectangular plates with an additional trapezoid element at the front. The head is also depicted wearing a nose-ring. The face is smiling and has wrinkles under the eyes and at the edge of the mouth. It has sagging cheeks and wide eyes.[104] The mouth is closed and the upper lip is badly damaged.[105] The sculpture suffered some mutilation in antiquity, with nine pits hollowed into the face and headdress.[106]

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 10 (also known as San Lorenzo Monument 89)[47] has been moved to the Museo Comunitario de San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán near Texistepec.[107] It stands 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) tall and measures 1.43 metres (4.7 ft) wide by 0.92 metres (3.0 ft) deep; it weighs 8 tons. The head was discovered by a magnetometer survey in 1994;[106] it was found buried, lying face upwards in the bottom of a ravine and was excavated by Ann Cyphers.[108] The headdress is formed of 92 circular beads that completely cover the upper part of the head and descend across the sides and back. Above the forehead is a large element forming a three-toed foot with long nails, possibly the foot of a bird. The head wears large earspools that protrude beyond the beads of the headdress. The spools have the form of a rounded square with a circular sunken central portion.[109] The face is that of a mature man with the mouth closed, sagging cheeks and lines under the eyes. The mouth is sensitively carved and the head possesses a pronounced chin.[110]

La Venta

Three of the La Venta heads were found in a line running east-west in the northern Complex I; all three faced northwards, away from the city centre.[111] The other head was found in Complex B to the south of the Great Pyramid, in a plaza that included a number of other sculptures.[112] The latter, the first of the La Venta heads to be discovered, was found during archaeological exploration of La Venta in 1925; the other three remained unknown to archaeologists until a local boy guided Matthew Stirling to them while he was excavating the first head in 1940. They were located approximately 0.9 kilometres (0.56 mi) to the north of Monument 1.[113]

La Venta Monument 1 is speculated to have been the portrait of La Venta's final ruler.[114] Monument 1 measures 2.41 metres (7.9 ft) high by 2.08 metres (6.8 ft) wide by 1.95 metres (6.4 ft) deep; it weighs 24 tons.[115] The front of the headdress is decorated with three motifs that apparently represent the claws or fangs of an animal. Above these symbols is an angular U-shaped decoration descending from the scalp. On each side of the monument a strap descends from the headdress, passing in front of the ear. Each ear has a prominent ear ornament that descends from the earlobe to the base of the monument. The features are those of a mature man, with wrinkles around the mouth, eyes and nose.[116] Monument 1 is the best preserved head at La Venta but has suffered from erosion, particularly at the back.[117] The head was first described by Franz Blom and Oliver La Farge who investigated the La Venta remains on behalf of Tulane University in 1925. When discovered, it was half-buried; its massive size meant that the discoverers were unable to excavate it completely. Matthew Stirling fully excavated the monument in 1940, after clearing the thick vegetation that had covered it in the intervening years. Monument 1 has been moved to the Parque-Museo La Venta in Villahermosa.[115] The head was found in its original context; associated finds have been radiocarbon dated to between 1000 and 600 BC.[116]

La Venta Monument 2 measures 1.63 metres (5.3 ft) high by 1.35 metres (4.4 ft) wide by 0.98 metres (3.2 ft) deep; the head weighs 11.8 tons.[116] The face has a broadly smiling expression that reveals four of the upper teeth. The cheeks are given prominence by the action of smiling; the brow that is normally visible in other heads is covered by the rim of the headdress.[118] The face is badly eroded, distorting the features.[119] In addition to the severe erosion damage, the upper lip and a part of the nose have been deliberately mutilated.[120] The head was found in its original context a few metres north of the northwest corner of pyramid-platform A-2. Radiocarbon dating of the monument's context dates it to between 1000 and 600 BC. Monument 2 has suffered erosion damage from its exposure to the elements prior to discovery. The head has a prominent headdress but this is badly eroded and any individual detail has been erased. A strap descends in front of the ear on each side of the head, descending as far as the earlobe. The head is adorned with ear ornaments in the form of a disc that covers the earlobe, with an associated clip or peg.[121] The surviving details of the headdress and earflares are stylistically similar to those of Tres Zapotes Monument A.[122] The head has been moved to the Museo del Estado de Tabasco in Villahermosa.[121]

La Venta Monument 3 stands 1.98 metres (6.5 ft) high and measures 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) wide by 1 metre (3.3 ft) deep; it weighs 12.8 tons. Monument 3 was located a few metres to the east of Monument 2, but was moved to the Parque-Museo La Venta in Villahermosa. Like the other La Venta heads, its context has been radiocarbon dated to between 1000 and 600 BC.[123] It appears unfinished and has suffered severe damage through weathering, making analysis difficult. It had a large headdress that reaches to the eyebrows but any details have been lost through erosion. Straps descend in front of each ear and continue to the base of the monument. The ears are wearing large flattened rings that overlap the straps; they probably represent jade ornaments of a type that have been recovered in the Olmec region. Although most of the facial detail is lost, the crinkling of the bridge of the nose is still evident, a feature that is common to the frowning expressions of the other Olmec colossal heads.[124]

La Venta Monument 4 measures 2.26 metres (7.4 ft) high by 1.98 metres (6.5 ft) wide and 1.86 metres (6.1 ft) deep. It weighs 19.8 tons. It was found a few metres to the west of Monument 2 and has been moved to the Parque-Museo La Venta.[125] As with the other heads in the group, its archaeological context has been radiocarbon dated to between 1000 and 600 BC. The headdress is elaborate and, although damaged, various details are still discernible. The base of the headdress is formed by three horizontal strips running over the forehead. One side is decorated with a double-disc motif that may have been repeated on the other; if so, damage to the right side has obliterated any trace of it.[126] The top of the headdress is decorated with the clawed foot of a bird of prey.[127] Either straps or plaits of hair descend on either side of the face, from the headdress to the base of the monument. Only one earspool survives; it is flat, in the form of a rounded square, and is decorated with a cross motif.[126] The ears have been completely eroded away and the lips are damaged.[128] The surviving features display a frown and creasing around the nose and cheeks.[129] The head displays prominent teeth.[130]

Tres Zapotes

The two heads at Tres Zapotes, with the La Cobata head,[132] are stylistically distinct from the other known examples. Beatriz de la Fuente views them as a late regional survival of an older tradition while other scholars argue that they are merely the kind of regional variant to be expected in a frontier settlement.[133] These heads are sculpted with relatively simple headdresses; they have squat, wide proportions and distinctive facial features.[134] The two Tres Zapotes heads are the earliest known stone monuments from the site.[135] The discovery of one of the Tres Zapotes heads in the nineteenth century led to the first archaeological investigations of Olmec culture, carried out by Matthew Stirling in 1938.[136]

Tres Zapotes Monument A (also known as Tres Zapotes Colossal Head 1) was the first colossal head to be found,[137] discovered by accident in the middle of the nineteenth century,[136] 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the north of the modern village of Tres Zapotes.[138] After its discovery it remained half-buried until it was excavated by Matthew Stirling in 1939.[139] At some point it was moved to the plaza of the modern village, probably in the early 1960s. It has since been moved to the Museo Comunitario de Tres Zapotes.[138] Monument A stands 1.47 metres (4.8 ft) tall;[140] it measures 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) wide by 1.45 metres (4.8 ft) deep,[137] and is estimated to weigh 7.8 tons.[140] The head is sculpted with a simple headdress with a wide band that is otherwise unadorned, and wears rectangular ear ornaments that project forwards onto the cheeks. The face is carved with deep creases between the cheeks and the nose and around the mouth; the forehead is creased into a frown.[138] The upper lip has suffered recent damage, with the left portion flaking away.[131]

Tres Zapotes Monument Q (also known as the Nestape Head and Tres Zapotes Colossal Head 2) measures 1.45 metres (4.8 ft) high by 1.34 metres (4.4 ft) wide by 1.26 metres (4.1 ft) deep and weighs 8.5 tons. Its exact date of discovery is unknown but is estimated to have been some time in the 1940s, when it was struck by machinery being used to clear vegetation from Nestape hill.[131] Monument Q was the eleventh colossal head to be discovered. It was moved to the plaza of Santiago Tuxtla in 1951 and remains there to this day.[141] Monument Q was first described by Williams and Heizer in an article published in 1965.[142] The headdress is decorated with a frontal tongue-shaped ornament, and the back of the head is sculpted with seven plaits of hair bound with tassels. A strap descends from each side of the headdress, passing over the ears and to the base of the monument. The face has pronounced creases around the nose, mouth and eyes.[143]

La Cobata

The La Cobata region was the source of the basalt used for carving all of the colossal heads in the Olmec heartland.[26] The La Cobata colossal head was discovered in 1970 and was the fifteenth to be recorded.[26] It was discovered in a mountain pass in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas, on the north side of El Vigia volcano near to Santiago Tuxtla.[144] The head was largely buried when found; excavations uncovered a Late Classic (600–900 AD) offering associated with the head consisting of a ceramic vessel and a 12-centimetre (4.7 in) long obsidian knife placed pointing northwards towards the head. The offering is believed to have been deposited long after the head was sculpted.[145] The La Cobata head has been moved from its original location to the main plaza at Santiago.[26]

The La Cobata head is more or less rounded and measures 3 by 3 metres (9.8 by 9.8 ft) by 3.4 metres (11 ft) high, making it the largest known head.[26] This massive sculpture is estimated to weigh 40 tons.[146] It is stylistically distinct from the other examples, and Beatriz de la Fuente placed it late in the Olmec time frame. The characteristics of the sculpture have led to some investigators suggesting that it represents a deceased person. Norman Hammond argues that the apparent stylistic differences of the monument stem from its unfinished state rather than its late production. The eyes of the monument are closed, the nose is flattened and lacks nostrils and the mouth was not sculpted in a realistic manner. The headdress is in the form of a plain horizontal band.[26]

The original location of the La Cobata head was not a major archaeological site and it is likely that the head was either abandoned at its source or during transport to its intended destination. Various features of the head suggest that it was unfinished, such as a lack of symmetry below the mouth and an area of rough stone above the base. Rock was not removed from around the earspools as on other heads, and does not narrow towards the base. Large parts of the monument seem to be roughed out without finished detail. The right hand earspool also appears incomplete; the forward portion is marked with a sculpted line while the rear portion has been sculpted in relief, probably indicating that the right cheek and eye area were also unfinished. The La Cobata head was almost certainly carved from a raw boulder rather than being sculpted from a throne.[26]

Takalik Abaj

Takalik Abaj Monument 23 dates to the Middle Preclassic period,[147] and is found in Takalik Abaj, an important city in the foothills of the Guatemalan Pacific coast,[38] in the modern department of Retalhuleu.[148] It appears to be an Olmec-style colossal head re-carved into a niche figure sculpture.[38] If originally a colossal head then it would be the only known example from outside the Olmec heartland.[39]

Monument 23 is sculpted from andesite and falls in the middle of the size range for confirmed colossal heads. It stands 1.84 metres (6.0 ft) high and measures 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) wide by 1.56 metres (5.1 ft) deep. Like the examples from the Olmec heartland, the monument features a flat back.[149] Lee Parsons contests John Graham's identification of Monument 23 as a re-carved colossal head;[150] he views the side ornaments, identified by Graham as ears, as rather the scrolled eyes of an open-jawed monster gazing upwards.[151] Countering this, James Porter has claimed that the re-carving of the face of a colossal head into a niche figure is clearly evident.[152]

Monument 23 was damaged in the mid-twentieth century by a local mason who attempted to break its exposed upper portion using a steel chisel. As a result, the top is fragmented, although the broken pieces were recovered by archaeologists and have been put back into place.[149]

Collections

All of the 17 confirmed colossal heads remain in Mexico. Two heads from San Lorenzo are on permanent display at the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.[153] Seven of the San Lorenzo heads are on display in the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa. Five of them are in Sala 1, one is in Sala 2, and one is in Patio 1.[154] The remaining San Lorenzo head is in the Museo Comunitario de San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán near Texistepec.[107] All four heads from La Venta are now in Villahermosa, the state capital of Tabasco. Three are in the Parque-Museo La Venta and one is in the Museo del Estado de Tabasco.[155] Two heads are on display in the plaza of Santiago Tuxtla; one from Tres Zapotes and the La Cobata Head.[156] The other Tres Zapotes head is in the Museo Comunitario de Tres Zapotes.[138]

Several colossal heads have been loaned to temporary exhibitions abroad; San Lorenzo Colossal Head 6 was loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1970.[80] San Lorenzo colossal heads 4 and 8 were lent to the Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico exhibition in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., which ran from 30 June to 20 October 1996.[157] San Lorenzo Head 4 was again loaned in 2005, this time to the de Young Museum in San Francisco.[158] The de Young Museum was loaned San Lorenzo colossal heads 5 and 9 for its Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico exhibition, which ran from 19 February to 8 May 2011.[159][160]

Vandalism

On 12 January 2009,[161] at least three people, including two Mexicans and one American, entered the Parque-Museo La Venta in Villahermosa and damaged just under 30 archaeological pieces, including the four La Venta colossal heads.[162][163] The vandals were all members of an evangelical church and appeared to have been carrying out a supposed pre-Columbian ritual, during which salts, grape juice, and oil were thrown on the heads.[164] It was estimated that 300,000 pesos (US$21,900) would be needed to repair the damage,[162] and the restoration process would last four months.[161] The three vandals were released soon after their arrest after paying 330,000 pesos each.[165]

Replicas

The majority of replicas around the world, though not all, were placed under the leadership of Miguel Alemán Velasco, former governor of the state of Veracruz.[166] The following is a list of replicas and their locations within the United States:

- Austin, Texas. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 1 was placed in the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas in November 2008.[167]

- Chicago, Illinois. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 8 made by Ignacio Perez Solano was placed in the Field Museum of Natural History in 2000.[168]

- Covina, California. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 5 was donated to Covina in 1989, originally intended to be placed in Jalapa Park. Due to concerns over potential vandalism it was instead installed outside the police station.[169] It was removed in 2011 and relocated to Jobe's Glen, Jalapa Park in June 2012.[170]

- McAllen, Texas. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 8 is located in the International Museum of Art & Science. The placement was dedicated by Fidel Herrera Beltrán, then governor of Veracruz.[171] This was done in 2010. The head is one of 12 sculpted by Ignacio Perez Solano and sent to various cities around the world.[172]

- New York. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 1 was placed next to the main plaza in the grounds of Lehman College in the Bronx, New York. It was installed in 2013 to celebrate the first anniversary of the CUNY Institute of Mexican Studies, housed at the college.[173] The replica was a gift by the government of Veracruz state, Cumbre Tajín and Mexico Trade;[174] it was first placed in Dag Hammerskjold Park, outside the United Nations, in 2012.[175]

- Paris, France. Since 2013, the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac displays a replica of San Lorenzo Head 8 in its public gardens.[176]

- San Francisco, California. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 1 created by Ignacio Perez Solano was placed in San Francisco City College, Ocean Campus in October 2004.[166][177]

- Washington, D.C. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 4 sculpted by Ignacio Perez Solano was placed near the Constitution Avenue entrance of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in October 2001.[178]

- West Valley City, Utah. A replica of San Lorenzo Head 8 was placed in the Utah Cultural Celebration Center in May 2004.[179]

- Todos Santos, Baja Sur, Mexico. A replica of a San Lorenzo Head 8 was sculpted in July 2018 by Mexican sculptor Benito Ortega Vargas. It is on the mound on the Camino a Las Playitas just north of Todos Santos.

Mexico donated a resin replica of an Olmec colossal head to Belgium; it is on display in the Art & History Museum in Brussels.[180]

In February 2010, the Mexican Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (Secretariat of Foreign Affairs) announced that the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia would be donating a replica Olmec colossal head to Ethiopia.[181] It was placed in Plaza Mexico in Addis Ababa in May 2010 and is locally known as the "Mexican Warrior".[182] Online conspiracy theory memes have surfaced claiming this is 'proof' of Africans arriving in the Americas before Columbus.[183]

In November 2017, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto donated a full-size replica of San Lorenzo Head 8 to the people of Belize. It was installed in Belmopan at the roundabout facing the Embassy of Mexico.[184]

See also

- Maya stelae

- Moai

- Monte Alto culture

- Stone spheres of Costa Rica

Citations

- Diehl 2004, p. 111.

- Taladoire 2018.

- Diehl 2004, pp. 11–12.

- Diehl 2004, p. 111. Pool 2007, p. 5.

- Diehl 2004, pp. 96–97.

- Taube summarizes recent contributions to the debate at pp. 41–42

- Taube, 6–12

- Taube, pp. 18–19; 24–25

- Taube, pp. 145–150

- de la Fuente 1996a, p. 42.

- Diehl 2004, p. 112.

- Diehl 2004, p. 112. Pool 2007, p. 118.

- de la Fuente 1996a, pp. 48–49.

- Pool 2007, pp. 7, 117–118, 251.

- Pool 2007, p. 106.

- Diehl 2004, pp. 111–112.

- Diehl 2004, p. 108.

- Diehl 2004, p. 109.

- de la Fuente 1996a, p. 48. Diehl 2004, pp. 112, 194c5n6.

- Diehl 2004, p.112. Cyphers 1996, p. 156.

- Skoglund, Pontus; Mallick, Swapan; Bortolini, Maria Cátira; Chennagiri, Niru; Hünemeier, Tábita; Petzl-Erler, Maria Luiza; Salzano, Francisco Mauro; Patterson, Nick; Reich, David (2015). "Genetic evidence for two founding populations of the Americas". Nature. 525 (7567): 104–108. Bibcode:2015Natur.525..104S. doi:10.1038/nature14895. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 4982469. PMID 26196601.

- Pool 2007, p. 118.

- Diehl 2011, pp. 193–194.

- Pool 2007, p. 110.

- Diehl 2004, p. 119.

- Hammond 2001.

- Gillespie 1994, p. 231.

- Killion and Urcid 2001, p. 6.

- Hammond 2001. Diehl 2004, p. 111.

- Diehl 2000, p. 164.

- Diehl 2004, p. 118.

- Hazell 2010, p. 2.

- Diehl 2011, p. 185.

- Hazell 2010, pp. 2, 5, 8.

- Pool 2007, p. 121.

- Hazell 2010, p. 9.

- Sources for all dimensions are cited in the text of the monument's description.

- Diehl 2004, p. 146.

- Pool 2007, p. 57.

- McInnis Thompson, and Valdez 2008, pp. 13, 17.

- McInnis Thompson, and Valdez 2008, p. 22.

- Diehl 2004, p. 146. Pool 2007, p. 57.

- Diehl 2004, p. 35. Pool 2007, p. 122.

- Pool 2007, p. 122.

- Diehl 2004, p. 35.

- Diehl 2004, p. 37.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 147.

- Diehl 2004, plate VI.

- Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 4.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 179.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 180. Pool 2007, p. 7.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 180. Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 9.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 180.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 179–180.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 181.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 182.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 183.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 184. SULAIR.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 184.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 184. Pool 2007, p. 7. Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 9.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 184–185.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 185–186.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 186.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 188.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 189.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 189–190.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 190.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 191.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 192.

- Cyphers 1996, p. 156.

- Cyphers 2007, p. 38.

- Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 69.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 193.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 193–194.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 194.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 195.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 196.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 196. Pool 2007, p. 7. Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p. 9.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 199.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 200.

- Miller 1986, 1996, pp. 20–21.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 197.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 198.

- Diehl 2004, p. 93.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 201.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 202–203.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 204.

- Breiner and Coe 1972, p. 5.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 206.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 207.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 208.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 205.

- Diehl 2000, p. 165.

- de la Fuente 1996b, p. 154. Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 211.

- Diehl 2004, pp. 39, plate VII.

- Diehl 2000, p. 165. Breiner and Coe 1972, p. 4.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 211.

- de la Fuente 1996b, p. 154.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 213.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 212, 214.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 214.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 215.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 216.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 217.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 218.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 219.

- Cyphers 2007, p. 36.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 219–220.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 220.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 221.

- Diehl 2004, pp. 62–63.

- Diehl 2004, p. 66.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 163, 168.

- Diehl 2004, plate V.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 163.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 164.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 166.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 169.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 170.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 171.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 168.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 168–169.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 172.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 173.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 175.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 176.

- Pool 2007, p. 166. Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 176.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 177–178.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 177.

- Pool 2007, p. 166.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 155.

- Diehl 2004, p. 46. Pool 2007, p. 251.

- Diehl 2004, p. 46.

- Pool 2007, p. 251.

- Pool 2007, p. 250.

- Diehl 2004, p. 182.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 151.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 152.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 152. Diehl 2004, p. 14.

- Diehl 2004, p. 14.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 156.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 155–156.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 157.

- Hammond 2001. Pool 2007, pp. 56, 251.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 160.

- Pool 2007, p. 56.

- Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 239.

- Kelly 1996, p. 210.

- Graham 1989, p. 233.

- Parsons 1986, p. 10.

- Parsons 1986, p. 19.

- Porter 1989, p. 26.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 184, 200.

- Museo de Antropología de Xalapa. Sala 1, Sala 2, Patio 1.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, pp. 163, 168, 172, 175.

- Casellas Cañellas 2004, p. 156. Hammond 2001.

- Benson and de la Fuente 1996, pp. 4, 154–157.

- Baker 6 October 2005.

- de Young Museum 2011.

- Hamlin 2011.

- López, 13 January 2009.

- La Crónica de Hoy, 13 January 2009.

- Guenter 2009.

- El Mañana, 12 January 2009. La Crónica de Hoy, 13 January 2009. López, 13 January 2009.

- La Crónica de Hoy, 14 January 2009.

- City College of San Francisco 2004.

- Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies 2008.

- Chicago Park District 2010.

- Funes April 2012.

- Covina City Hall undated. Funes June 2012.

- IMAS undated.

- Perez, 27 January 2010.

- CUNY Mexican Studies Institute 5 June 2013.

- CUNY Mexican Studies Institute 5 June 2013. Embajada de México en Estados Unidos 7 June 2013.

- Kappstatter 17 June 2013.

- "PRECOLOMBIEN - Paris accueille la réplique d'une tête colossale olmèque". precolombien.free.fr. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- Bergman, Sherer Mathes and White 2010, p. 48.

- Smithsonian 2012. Coronado Ruiz 2008–2009, p. 31.

- West Valley City Hall undated. Bulkeley 2004.

- Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire.

- Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, 2 February 2010.

- "Manual de Organización de la Embajada de México en Etiopía" (PDF). Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores: 7. January 2012.

- Parks, Forest (2017-06-22). "Here's Why Identical "Black" Olmec Statues In Mexico And Ethiopia DOESN'T PROVE A Thing". Urban Intellectuals. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- Nuñez, 6 November 2017.

References

- Baker, Kenneth (6 October 2005). "Behold the new de Young. Now take a look inside". San Francisco, California, USA: SFGate, home of the San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved 2012-05-07.

- Bergman, Julia; Valerie Sherer Mathes; Austin White (2010). City College of San Francisco. The Campus History Series. San Francisco, California, USA: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0738581347. OCLC 672010511. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- Breiner, Sheldon; Michael D. Coe (September–October 1972). "Magnetic Exploration of the Olmec Civilization" (PDF). American Scientist. Vol. 60, no. 5. New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Sigma Xi. ISSN 0003-0996. OCLC 1480717. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- Bulkeley, Deborah (23 May 2004). "Mexican Olmec head is a big hit in West Valley". Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA: Deseret News Publishing Co. ISSN 0745-4724. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- Casellas Cañellas, Elisabeth (2004). "El Contexto Arqueológico de la Cabeza Colosal Olmeca Número 7 de San Lorenzo, Veracruz, México" [The Archaeological Context of Olmec Colossal Head 7 from San Lorenzo, Veracruz, Mexico] (PDF) (in Spanish). Barcelona, Spain: Autonomous University of Barcelona. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- Chicago Park District (2010). "Grant Park Olmec Head" (PDF). Chicago, Illinois, USA: Chicago Park District. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- City College of San Francisco (2004). "City College to Dedicate Olmec Head October 9". San Francisco, California, USA: City College of San Francisco. Archived from the original on 2012-12-12. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (2002) [1962]. Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (5th, revised and enlarged ed.). London, UK and New York, USA: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28346-2. OCLC 50131575.

- Coronado Ruiz, Anabella (2008–2009). "Olmec Landmark for LLILAS" (PDF). Portal. Austin, Texas, USA: Teresa Lozano Institute of Latin American Studies (4): 30–33. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- Covina City Hall (n.d.). "Olmec Head". Covina, California, USA: City of Covina official website. Archived from the original on 2013-04-21. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- CUNY Institute of Mexican Studies (5 June 2013). "Replica Olmec Head of 'The King' Moves to Lehman". New York, USA: Lehman College. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- Cyphers, Ann (1996). "Item 2. San Lorenzo Monument 4". In Elizabeth P. Benson; Beatriz de la Fuente (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington, D.C., USA: National Gallery of Art. pp. 41–49. ISBN 978-0-8109-6328-3. OCLC 34357584.

- Cyphers, Ann (September–October 2007). "Surgimiento y decadencia de San Lorenzo, Veracruz" [Rise and Fall of San Lorenzo, Veracruz]. Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Raíces. XV (87): 36–42. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 29789840.

- de la Fuente, Beatriz (1996a). "Homocentrism in Olmec Monumental Art". In Elizabeth P. Benson; Beatriz de la Fuente (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington, D.C., USA: National Gallery of Art. pp. 41–49. ISBN 978-0-8109-6328-3. OCLC 34357584.

- de la Fuente, Beatriz (1996b). "Item 1. San Lorenzo Monument 61- Colossal Head 8". In Elizabeth P. Benson; Beatriz de la Fuente (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington, D.C., USA: National Gallery of Art. pp. 41–49. ISBN 978-0-8109-6328-3. OCLC 34357584.

- de Young Museum (2011). "Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico". San Francisco, California, USA: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Retrieved 2012-05-07.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2000). "The Precolumbian Cultures of the Gulf Coast". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 156–196. ISBN 978-0-521-35165-2. OCLC 33359444.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Ancient peoples and places series. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-02119-4. OCLC 56746987.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2011). "De cómo los reyes olmecas obtenían sus cabezas colosales" [On how the Olmec kings obtained their colossal heads]. In Eduardo Williams; Magdalena García Sánchez; Phil C. Weigand; Manuel Gándara (eds.). Mesoamérica: Debates y perspectivas [Mesoamerica: Debates and perspectives] (in Spanish). Zamora, Michoacán, Mexico: Colegio de Michoacán. ISBN 978-607-7764-80-9. OCLC 784363836.

- El Mañana (12 January 2009). "Dañan Cabeza Olmeca y 27 piezas arqueológicas más" [Olmec head and 27 other pieces damaged]. El Mañana (in Spanish). Nuevo Laredo, Mexico: Editora Argos. OCLC 30499034. Archived from the original on 2013-02-21. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- Embajada de México en Estados Unidos (7 June 2013). "El Embajador Eduardo Medina Mora realizó una visita de trabajo a Nueva York" [Ambassador Eduardo Mora carries out a working visit to New York] (in Spanish). Washington, D. C., USA: Embajada de México en Estados Unidos. Archived from the original on 2013-07-17. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- Funes, Juliette (29 April 2012). "Covina officials to reconsider relocating 7-ton Olmec head". SGV Tribune. West Covina, California, USA: Los Angeles Newspaper Group. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- Funes, Juliette (11 June 2012). "Olmec head settling in at new home in Covina park". SGV Tribune. West Covina, California, USA: Los Angeles Newspaper Group. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- Gillespie, Susan D. (1994). "Llano del Jicaro: An Olmec monument workshop". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 5 (2): 231–242. doi:10.1017/S095653610000119X. S2CID 162555208.

- Graham, John (1989). "Olmec diffusion: a sculptural view from Pacific Guatemala". In Robert J. Sharer; David C. Grove (eds.). Regional perspectives on the Olmec. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–246. ISBN 978-0-521-36332-7. OCLC 18289933.

- Guenter, Stanley (2009). "Vandalism to Olmec Monuments in Villahermosa". Mesoweb reports. Mesoweb: An Exploration of Mesoamerican Cultures. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Hammond, Norman (March 2001). "The Cobata colossal head: an unfinished Olmec monument?". Antiquity. Antiquity Publications Ltd. via HighBeam Research. 75 (287): 21–22. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00052595. S2CID 163119230. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2012-05-05.(subscription required)

- Hamlin, Jesse (13 February 2011). "Big 'Olmec' show coming to de Young Museum". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- Hazell, Leslie C. (11 October 2010). "Analysing route and transport strategies to retrieve stones used by Olmec society for the San Lorenzo colossal heads". Una Vida de Arqueología Preclásica: Jornadas en Homenaje a la Dra. Ann Cyphers. Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico: Museo de Antropología de Xalapa-Universidad Veracruzana.

- IMAS (n.d.). "Sculpture Garden". McAllen, Texas, USA: International Museum of Art & Science. Archived from the original on 2018-09-26. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- Kappstatter, Bob (17 June 2013). "Royalty' at Lehman College". Bronx Times. Community Newspaper Group. Archived from the original on 2013-09-02.

- Kelly, Joyce (1996). An Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Norman, Oklahoma, USA: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2858-0. OCLC 34658843.

- Killion, Thomas W.; Javier Urcid (2001). "The Olmec Legacy: Cultural Continuity and Change in Mexico's Southern Gulf Coast Lowlands" (PDF). Journal of Field Archaeology. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Boston University. 28 (1/2): 3–25. doi:10.2307/3181457. ISSN 0093-4690. JSTOR 3181457. OCLC 1798634.

- La Crónica de Hoy (13 January 2009). "Una estadunidense, entre detenidos por vandalismo contra piezas olmecas" [American among those arrested for vandalism of Olmec artefacts]. La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: cronica.com.mx. OCLC 35957746. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- La Crónica de Hoy (14 January 2009). "Vándalos de piezas olmecas, libres tras pagar $390 mil" [Vandals of Olmec artefacts free after paying 390 thousand pesos]. La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: cronica.com.mx. OCLC 35957746. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- López, René Alberto (13 January 2009). "Dañan cabeza olmeca en el Museo La Venta" [Olmec head damaged in the La Venta Museum]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: DEMOS, Desarrollo de Medios. ISSN 0188-2392. OCLC 14208832. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- McInnis Thompson, Lauri; Fred Valdez Jr. (2008). "Potbelly Sculpture: An Inventory and Analysis". Ancient Mesoamerica. USA: Cambridge University Press. 19 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1017/S0956536108000278. S2CID 165615759.

- Miller, Mary Ellen (1996) [1986]. The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec. World of Art series (3rd ed.). London, UK: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20345-3. OCLC 59530512.

- Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire. "Amérique précolombienne" [Pre-Columbian America] (in French). Brussels, Belgium: Services Publics Fédéraux Belges. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- Museo de Antropología de Xalapa. "Colección Museo de Antropología de Xalapa" [Xalapa Museum of Anthropology Collection] (in Spanish). Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico: Museo de Antropología de Xalapa. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2012-05-07.

- Nuñez, Dorian (6 November 2017). "Colossal Olmec Head Offered by Mexico as Gift to Belizean People". Ambergriz Today. San Pedro Town, Ambergris Caye, Belize. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Parsons, Lee Allen (1986). "The Origins of Maya Art: Monumental Stone Sculpture of Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala, and the Southern Pacific Coast". Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.: Trustees for Harvard University. 28 (28): i–216. ISSN 0585-7023. JSTOR 41263466. (subscription required)

- Perez, Pedro IV (27 January 2010). "The new face in town". Valley Town Crier. McAllen, Texas, US. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Pool, Christopher A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3. OCLC 68965709.

- Porter, James B. (Spring–Autumn 1989). "Olmec Colossal Heads as Recarved Thrones: "Mutilation," Revolution, and Recarving". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The President and Fellows of Harvard College acting through the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. 17–18 (17/18): 22–29. doi:10.1086/RESvn1ms20166812. JSTOR 20166812. S2CID 193558188. (subscription required)

- Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (2 February 2010). "México fortalece sus vínculos con áfrica" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

- Smithsonian (2012). "Outdoor Sculptures, including Sculptures from Nature". Washington, D. C., USA: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- SULAIR. "The Olmec tradition; [exhibition] June 18 to August 25, 1963". Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Libraries and Academic Information Resources (SULAIR). Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- Taladoire, Eric (11 October 2018). "Melgar, Fuzier y la cabeza olmeca de Hueyapan, Veracruz". Arqueología Mexicana. Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Raíces. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Taube, Karl A. (2004). Olmec Art At Dumbarton Oaks. Pre-Columbian art at Dumbarton Oaks. Vol. 2. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884022756. OCLC 56096117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies (2008). "Olmec Head Sculpture Donated to LLILAS". Austin, Texas, USA: University of Texas College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- West Valley City Hall (n.d.). "Permanent Collection". West Valley City Hall, West Valley City, Utah, USA. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

Further reading

- Baudez, Claude-François (January 2012). "Beauty and ugliness in Olmec monumental sculpture". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. OpenEdition. 98 (98–2): 7–31. doi:10.4000/jsa.12294. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Clewlow, C. William; Richard A. Cowan; James F. O'Connell; Carlos Benemann (October 1967). Colossal Heads of the Olmec Culture (PDF). Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility. Vol. 4. Berkeley, California, USA: University of California Department of Anthropology. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- Harvey, Ian (20 February 2017). "Mexico's "Olmec Colossal Heads" are a mystery as to their age and their method of construction". The Vintage News. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Hazell, Leslie C. (2008). "Using Environmental constraints, Human Power Capability and Technological Performance as Parameters to Investigate transport of Megaliths Using Canoe Rafts by Olmec Society in Mesoamerica". Flowing Through Time: Exploring Archaeology Through Humans and Their Aquatic Environment. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: The Archaeological Association of the University of Calgary. pp. 56–67. hdl:1959.9/120155. ISBN 978-0-88953-330-1. OCLC 746470737.

- Hazell, Leslie C.; Graham Brodie (2012). "Applying GIS tools to define prehistoric megalith transport route corridors: Olmec megalith transport routes: a case study". Journal of Archaeological Science. London, UK: Academic Press. 39 (11): 3475. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.05.015. ISSN 0305-4403. OCLC 36982975.

- Heizer, Robert F.; Tillie Smith; Howel Williams (July 1965). "Notes on Colossal Head No. 2 from Tres Zapotes". American Antiquity. Washington, D.C., USA: Society for American Archaeology. 31 (1): 102–104. doi:10.2307/2694027. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 2694027. OCLC 1479302. S2CID 163679244. (subscription required)

- Minster, Christopher (27 December 2017). "The Olmec City of San Lorenzo". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Patrick, Neil (20 July 2016). "Olmec colossal heads: Massive boulder heads in Central America remain a mystery …". The Vintage News. Retrieved 15 September 2018.