Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action.[1] Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issues, such as defense, foreign relations, internal trade or currency, with the central government being required to provide support for all its members. Confederalism represents a main form of intergovernmentalism, which is defined as any form of interaction around states which takes place on the basis of sovereign independence or government.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms of government |

|

|

The nature of the relationship among the member states constituting a confederation varies considerably. Likewise, the relationship between the member states and the general government and the distribution of powers among them varies. Some looser confederations are similar to international organisations. Other confederations with stricter rules may resemble federal systems.

Since the member states of a confederation retain their sovereignty, they have an implicit right of secession. The political philosopher Emmerich de Vattel said: "Several sovereign and independent states may unite themselves together by a perpetual confederacy without each in particular ceasing to be a perfect state.... The deliberations in common will offer no violence to the sovereignty of each member".[2]

Under a confederation, compared to a federal state, the central authority is relatively weak.[3] Decisions made by the general government in a unicameral legislature, a council of the member states, require subsequent implementation by the member states to take effect; they are not laws acting directly upon the individual but have more the character of interstate agreements.[4] Also, decision-making in the general government usually proceeds by consensus (unanimity), not by majority. Historically, those features limit the effectiveness of the union and so political pressure tends to build over time for the transition to a federal system of government, as happened in the American, Swiss and German cases of regional integration.

Confederated states

In terms of internal structure, every confederal state is composed of two or more constituent states, that are referred to as confederated states. In regard to their political systems, confederated states can have republican or monarchical forms of government. Those that have republican form (confederated republics) are usually called states (like states of the American Confederacy, 1861-1865) or republics (like republics of Serbia and Montenegro within the former State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, 2003-2006).[5] Those that have monarchical form of government (confederated monarchies) are defined by various hierarchical ranks (like kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan within the Hashemite Arab Union in 1958).

Examples

Belgium

Many scholars have claimed that the Kingdom of Belgium, a country with a complicated federal structure, has adopted some characteristics of a confederation under the pressure of separatist movements, especially in Flanders. For example, C. E. Lagasse declared that Belgium was "near the political system of a Confederation" regarding the constitutional reform agreements between Belgian Regions and between Communities,[6] and the director of the Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques (CRISP) Vincent de Coorebyter[7] called Belgium "undoubtedly a federation...[with] some aspects of a confederation" in Le Soir.[8] Also in Le Soir, Professor Michel Quévit of the Catholic University of Leuven wrote that the "Belgian political system is already in dynamics of a Confederation".[9][10]

Nevertheless, the Belgian regions and the linguistic communities do not have the necessary autonomy to leave the Belgian state. As such, federal aspects still dominate. Also, for fiscal policy and public finances, the federal state dominates the other levels of government.

The increasingly-confederal aspects of the Belgian Federal State appear to be a political reflection of the profound cultural, sociological and economic differences between the Flemish (Belgians who speak Dutch or Dutch dialects) and the Walloons (Belgians who speak French or French dialects).[11] For example, in the last several decades, over 95% of Belgians have voted for political parties that represent voters from only one community, the separatist N-VA being the party with the most voter support among the Flemish population. Parties that strongly advocate Belgian unity and appeal to voters of both communities play usually only a marginal role in nationwide general elections. The system in Belgium is known as consociationalism.[12][13]

That makes Belgium fundamentally different from federal countries like Switzerland, Canada, Germany and Australia. In those countries, national parties regularly receive over 90% of voter support. The only geographical areas comparable with Belgium within Europe are Catalonia, the Basque Country (both part of Spain), Northern Ireland and Scotland (both part of the United Kingdom) and parts of Italy, where a massive voter turnout for regional (and often separatist) political parties has become the rule in the last decades, and nationwide parties advocating national unity draw around half or sometimes less of the votes.

Benelux

The Benelux is a politico-economic union of the states of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg bound through treaties and based on consensus between the representatives of the member states.

They partially share a common foreign policy, especially in regards to their navies through the BeNeSam. The Dutch defence minister (2010-2012) Hans Hillen even said on Belgian radio that it is not impossible that the three armed forces of the member-states could be integrated into "Benelux Armed Forces" one day.

Because of this the Benelux is sometimes labeled as a "kind of confederation" by, for example; Belgian Minister of State Mark Eyskens.[14][15]

Canada

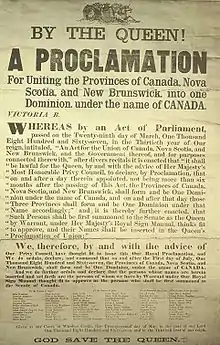

In Canada, the word confederation has an additional unrelated meaning.[16] "Confederation" refers to the process of (or the event of) establishing or joining the Canadian federal state.

In modern terminology, Canada is a federation, not a confederation.[17] However, to contemporaries of the Constitution Act, 1867, confederation did not have the same connotation of a weakly-centralized federation.[18] Canadian Confederation generally refers to the Constitution Act, 1867, which formed the Dominion of Canada from three of the colonies of British North America, and to the subsequent incorporation of other colonies and territories. Beginning on 1 July 1867, it was initially a self-governing dominion of the British Empire with a federal structure, whose government was led by Sir John A. Macdonald. The initial colonies involved were the Province of Canada (becoming Quebec from Canada East, formerly the colony of Lower Canada; and Ontario from Canada West, formerly the colony of Upper Canada), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. Later participants were Manitoba, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Alberta and Saskatchewan (the latter two created in 1905 as federated provinces from parts of the directly federally administered Northwest Territories, first transferred to the Dominion in 1869 and now possessing devolved governments as itself, Yukon and Nunavut), and finally Newfoundland (now Newfoundland and Labrador) in 1949. Canada is an unusually decentralized federal state, not a confederate association of sovereign states,[16] the usual meaning of confederation in modern terms. A Canadian judicial constitutional interpretation, Reference Re Secession of Quebec, and a subsequent federal law, set forth negotiating conditions for a Canadian province (though not a territory) to leave the Canadian federal state (addressed also by a related Quebec law). Importantly, negotiation would first need triggering by referendum and executing by constitutional amendment using a current amending mechanism of Canada’s constitution—meaning that, while not legal under the current constitution, it is democratically feasible without resorting to extralegal means or international involvement.

European Union

Its unique nature and the political sensitivities surrounding it cause there to be no common or legal classification for the European Union (EU). However, it bears some resemblance to both a confederation[19] (or a "new" type of confederation) and a federation.[20] The term supranational union has also been applied. The EU operates common economic policies with hundreds of common laws, which enable a single economic market, a common customs territory, (mainly) open internal borders, and a common currency among most member-states. However, unlike a federation, the EU does not have exclusive powers over foreign affairs, defence, and taxation. Furthermore, most EU laws, which have been developed by consensus between relevant national government ministers and then scrutinised and approved or rejected by the European Parliament, must be transposed into national law by national parliaments. Most collective decisions by member states are taken by weighted majorities and blocking minorities typical of upper houses in federations. On the other hand, the absolute unanimity typical of intergovernmentalism is required only in respect to the Common Foreign and Security Policy, as well as in situations when ratification of a treaty or of a treaty amendment is required. Such a form may thus be described as a semi-intergovernmental confederation.

However, some academic observers more usually discuss the EU in the terms of it being a federation.[21][22] As the international law professor Joseph H. H. Weiler (of the Hague Academy and New York University) wrote, "Europe has charted its own brand of constitutional federalism".[23] Jean-Michel Josselin and Alain Marciano see the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg City as being a primary force behind the building of a federal legal order for the EU,[24] with Josselin stating that a "complete shift from a confederation to a federation would have required to straight-forwardly replace the principality of the member states vis-à-vis the Union by that of the European citizens. As a consequence, both confederate and federate features coexist in the judicial landscape".[25] Rutgers political science professor R. Daniel Kelemen said: "Those uncomfortable using the 'F' word in the EU context should feel free to refer to it as a quasi-federal or federal-like system. Nevertheless, the EU has the necessary attributes of a federal system. It is striking that while many scholars of the EU continue to resist analyzing it as a federation, most contemporary students of federalism view the EU as a federal system".[26] Thomas Risse and Tanja A. Börzel claim that the "EU only lacks two significant features of a federation. First, the Member States remain the 'masters' of the treaties, i.e., they have the exclusive power to amend or change the constitutive treaties of the EU. Second, the EU lacks a real 'tax and spend' capacity, in other words, there is no fiscal federalism".[27]

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, the chairman of the body of experts commissioned to elaborate a constitutional charter for the European Union, was confronted with strong opposition from the United Kingdom towards including the words 'federal' or 'federation' in the unratified European Constitution and the word was replaced with either 'Community' or 'Union'.[28]

A majority of the Political Groups in the European Parliament, including the EPP, the S&D Group and Renew Europe, support a federal model for the European Union. The ECR Group argues for a reformed European Union along confederal lines. The Brothers of Italy party, led by Giorgia Meloni, campaigns for a confederal Europe. On her election as President of the ECR Party in September 2020 Meloni said, "Let us continue to fight together for a confederate Europe of free and sovereign states".[29][30]

Indigenous confederations in North America

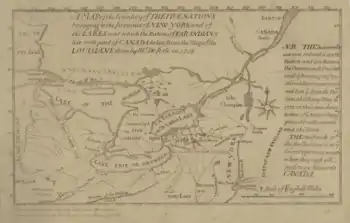

In the context of the history of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, a confederacy may refer to a semi-permanent political and military alliance consisting of multiple nations (or "tribes", "bands", or "villages"), which maintained their separate leadership. One of the most well-known is the Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois), but there were many others during different eras and locations across North America, such as the Wabanaki Confederacy, Western Confederacy, Powhatan, Seven Nations of Canada, Pontiac's Confederacy, Illinois Confederation, Tecumseh's Confederacy, Great Sioux Nation, Blackfoot Confederacy, Iron Confederacy and Council of Three Fires.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, historically known as the Iroquois League or the League of Five (later Six) Nations, is the country of Native Americans (in what is now the United States) and First Nations (in what is now Canada) that consists of six nations: the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Cayuga, the Seneca and the Tuscarora. The Six Nations have a representative government known as the Grand Council which is the oldest governmental institution still maintaining its original form in North America.[31] Each clan from the five nations sends chiefs to act as representatives and make decisions for the whole confederation. It has been operating since its foundation in 1142 despite limited international recognition today.

Serbia and Montenegro

In 2003, Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was transformed into the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, a confederation of the Republic of Montenegro and the Republic of Serbia. The state was constituted as a loose political union, but formally functioned as a sovereign subject of international law, and member of the United Nations. As a confederation, the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro had very few shared functions, such as defense, foreign affairs and a weak common president, ministerial council and parliament.[5]

The two constituent republics functioned separately throughout the period of its short existence, and they continued to operate under separate economic policies and to use separate currencies (the euro was and still is the only legal tender in Montenegro, and the dinar was and still is the legal tender in Serbia). On 21 May 2006, the Montenegrin independence referendum was held. The final official results indicated on 31 May that 55.5% of voters voted in favor of independence. The confederation effectively came to an end after Montenegro's formal declaration of independence on 3 June 2006 and Serbia's formal declaration of independence on 5 June.

Switzerland

Switzerland, officially known as the Swiss Confederation,[32][33][34] is an example of a modern country that traditionally refers to itself as a confederation because the official (and traditional) name of Switzerland in German (the majority language of the Swiss) is Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft (literally "Swiss Comradeship by Oath"), an expression which was translated into the Latin Confoederatio Helvetica (Helvetic Confederation). It had been a confederacy since its inception in 1291 as the Old Swiss Confederacy, which was originally created as an alliance among the valley communities of the central Alps, until it became a federation in 1848 but it retains the name of Confederacy for reasons of historical tradition. The confederacy facilitated management of common interests (such as freedom from external domination especially from the Habsburg Empire, the development of republican institutions in a Europe dominated by monarchies and free trade), and it ensured peace between the different cultural entities of the area.

After the Sonderbund War of 1847, when some of the Catholic cantons of Switzerland attempted to set up a separate union (Sonderbund in German) against the Protestant majority, a vote was held and the majority of the cantons approved the new Federal Constitution which changed the political system to one of a federation.[35][36]

Union State of Russia and Belarus

In 1999, Russia and Belarus signed a treaty to form a confederation,[37] which came into force on 26 January 2000.[38] Although it was given the name Union State, and has some characteristics of a federation, it remains a confederation of two sovereign states.[39] Its existence has been seen as an indication of Russia’s political and economic support for the Belarusian government.[40] The confederation was created with the objective of co-ordinating common action on economic integration and foreign affairs.[39] However, many of the treaty’s provisions have not yet been implemented.[40] Consequently, The Times, in 2020, described it as “a mostly unimplemented confederation”.[41]

Historical confederations

Historical confederations (especially those predating the 20th century) may not fit the current definition of a confederation, may be proclaimed as a federation but be confederal (or the reverse), and may not show any qualities that 21st-century political scientists might classify as those of a confederation.

List

Some have more the characteristics of a personal union, but appear here because of their self-styling as a "confederation":

| Name | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Three Crowned Kings | 1050 BCE–second century BCE | As described in the Hathigumpha inscription, On the 11th year, Kharavela broke up a confederacy of Tamil kingdoms, which was becoming a threat to Kalinga Kharavela |

| 496–1122 | Existed as a confederation between the Toltecs and the Chichimeca, simultaneously as an empire exerting control over places like Cholula. | |

| 800–1804 | Formally an empire, de facto a confederation of mainly German, Italian, Czech, and French states that was formally the most populous realm in Europe for over a thousand years. | |

| Kimek–Kipchak confederation | 9th century–13th century | A Turkic confederation in the eastern part of the Eurasian Steppe, between the 9th and 13th centuries. The confederation was dominated by two Turkic nomadic tribes: the Kimeks and the Kipchaks. |

| Cumania | 10th century–1242 | A Turkic confederation in the western part of the Eurasian Steppe, between the 10th and 13th centuries. The confederation was dominated by two Turkic nomadic tribes: the Cumans and the Kipchaks. |

| League of Mayapan | 987–1461 | |

| 1137–1716 | ||

| 1142–present | Also known as the Iroquois Confederacy or the Six (formerly Five) Nations. | |

| 13th–17th centuries | ||

| 1291–1848 | Officially, the "Swiss Confederation". | |

| Kara Koyunlu | 1375–1468 | A Turkoman tribal confederation. |

| Aq Qoyunlu | 1379–1501 | A Turkoman tribal confederation. |

| 1397–1523 | Denmark, Sweden, Norway. | |

| 1428–1521 | Consisted of the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan. | |

| 1435–1561 | ||

| 1447–1492 1501–1569 |

Shared a monarch (Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland), parliament (Sejm) and currency. | |

| 1536–1814 | ||

| 1581–1795 | ||

| Wampanoag Confederacy | ||

| Powhatan Confederacy | ||

| Illinois Confederation | ||

| 1641–1649 | ||

| 1643–1684 | ||

| Kingdom of Lunda | c. 1665-1887 |

|

| 1690–1902 | Parts of present-day Nigeria, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. | |

| 1781–1789 | Organization of the United States under the Articles of Confederation | |

| Western Confederacy | 1785–1795 | |

| 1806–1813 | Had no head of state nor government. | |

| 1815–1866 | ||

| 1810–1816 | Now part of present-day Colombia. | |

| 1814–1905 | ||

| 1824 | Located in northeast Brazil. | |

| 1832–1860 | ||

| 1836–1839 | ||

| Confederation of Central America | 1842–1844 | Present-day El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. |

| 1858–1863 | ||

| 1861–1865 | Southern US secessionist states during the American Civil War. | |

| 1872–1876 | Spanish states. | |

| 1917–1922 | ||

| 1921–1926 | Also known as the Rif Republic. Short-lived republic in Spanish-occupied northern Morocco during the Rif War. | |

| 1945–present | ||

| 1953–1963 | Also known as the Central African Federation, consisting of the then-British colonies of Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland (current-day Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi.) | |

| 1958 | Iraq and Jordan. | |

and the United Arab Statesb |

1958–1961 | Egypt and Syria, joined by North Yemen. |

| 1961–1963 | Mali, Ghana and Guinea. | |

| 1972 | Egypt, Syria and Libya. | |

| 1974 | Libya and Tunisia. | |

| Senegambia | 1982–1989 | Senegal and Gambia. |

| 1994–present | ||

| 2002–present | ||

| 2003–2006 | ||

- a Confederated personal union.

- b De facto confederation.

See also

- Associated state

- Commonwealth

- Federalism

- Federation

- List of confederations

References

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Vattel, Emmerich (1758) The Law of Nations, cited in Wood, Gordon (1969) The Creation of the American Republic 1776 - 1787, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, p.355.

- McCormick, John (2002) Understanding the European Union: a Concise Introduction, Palgrave, Basingstoke, p. 6.

- This was the key feature that distinguished the first American union, under the Articles of Confederation of 1781, from the second, under the current US Constitution of 1789. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 15, called the absence of directly-effective law in the Articles a "defect" and the "great and radical vice" in the initial system. Madison, James, Hamilton, Alexander and Jay, John (1987) The Federalist Papers, Penguin, Harmondsworth, p. 147.

- Miller 2005, p. 529–581.

- French Le confédéralisme n'est pas loin Charles-Etienne Lagasse, Les Nouvelles institutions politiques de la Belgique et de l'Europe, Erasme, Namur 2003, p. 405 ISBN 2-87127-783-4

- "Belgian research center whose activities are devoted to the study of decision-making in Belgium and in Europe". Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- French: "La Belgique est (...) incontestablement, une fédération : il n’y a aucun doute (...) Cela étant, la fédération belge possède d’ores et déjà des traits confédéraux qui en font un pays atypique, et qui encouragent apparemment certains responsables à réfléchir à des accommodements supplémentaires dans un cadre qui resterait, vaille que vaille, national." Vincent de Coorebyter "La Belgique (con)fédérale" in Le Soir 24 June 2008

- French: Le système institutionnel belge est déjà inscrit dans une dynamique de type cs, Le Soir, 19 September 2008

- Robert Deschamps, Michel Quévit, Robert Tollet, "Vers une réforme de type confédéral de l'État belge dans le cadre du maintien de l'union monétaire," in Wallonie 84, n°2, pp. 95-111

- Le petit Larousse 2013 p1247

- Wolff, Stefan (2004). Disputed Territories: The Transnational Dynamics of Ethnic Conflict Settlement. Berghahn Books. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9781571817181.

- Wippman, David (1998). "Practical and Legal Constraints on Internal Power Sharing". In Wippman, David (ed.). International Law and Ethnic Conflict. Cornell University Press. p. 220. ISBN 9780801434334.

- Eyskens, Mark (2 August 2021). "'Een Belgische confederatie leidt onvermijdelijk tot drie onafhankelijke staten'". Site-Knack-NL (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- VRG-Alumni (13 February 2020). Recht in beweging - 27ste VRG-Alumnidag 2020 (in Dutch). Gompel&Svacina. ISBN 978-94-6371-204-0.

- Eugene A. Forsey, How Canadians Govern Themselves, 9th ed. (Ottawa: Library of Parliament / Bibliothèque du Parlement, Catalogue No. X9‑11/2016E, 2016‑03), ISBN 978‑0‑660‑04488‑0, pp. 7, 29. French version published as Les Canadiens et leur système de gouvernement, no de catalogue X9‑11/2016F, ISBN 978‑0‑660‑04491‑0. First edition published in 1980.

- P.W. Hogg, Constitutional Law of Canada (5th ed. supplemented), para. 5.1(b).

- Waite, Peter B. (1962). The Life and Times of Confederation, 1864–1867. University of Toronto Press. Pages 37–38, footnote 6.

- Kiljunen, Kimmo (2004). The European Constitution in the Making. Centre for European Policy Studies. pp. 21–26. ISBN 978-92-9079-493-6.

- Burgess, Michael (2000). Federalism and European union: The building of Europe, 1950–2000. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 0-415-22647-3. "Our theoretical analysis suggests that the EC/EU is neither a federation nor a confederation in the classical sense. But it does claim that the European political and economic elites have shaped and moulded the EC/EU into a new form of an international organization, namely, a species of "new" confederation."

- Josselin, Jean Michel; Marciano, Alain (2006). "The Political Economy of European Federalism" (PDF). Series: Public Economics and Social Choice. Centre for Research in Economics and Management, University of Rennes 1, University of Caen: 12. WP 2006-07; UMR CNRS 6211. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008.

A complete shift from a confederation to a federation would have required to straightforwardly replace the principalship of the member states vis-à-vis the Union by that of the European citizens. As a consequence, both confederate and federate features coexist in the judicial landscape.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "How the Court Made a Federation of the EU" [referring to the European Court of Justice]. Josselin (U. de Rennes-1/CREM) and Marciano (U. de Reims CA/CNRS).

- J.H.H. Weiler (2003). "Chapter 2, Federalism without Constitutionalism: Europe's Sonderweg". The federal vision: legitimacy and levels of governance in the United States and the European Union. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924500-2.

Europe has charted its own brand of constitutional federalism. It works. Why fix it?

- How the [ECJ] court made a federation of the EU Josselin (U de Rennes-1/CREM) and Marciano (U de Reims CA/CNRS).

- Josselin, Jean Michel; Marciano, Alain (2006). "The political economy of European federalism" (PDF). Series: Public Economics and Social Choice. Centre for Research in Economics and Management, University of Rennes 1, University of Caen: 12. WP 2006-07; UMR CNRS 6211. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bednar, Jenna (2001). A Political Theory of Federalism. Cambridge University. pp. 223–270.

- Thomas Risse and Tanja A. Börzel, Who is Afraid of a European Federation? How to Constitutionalise a Multi-Level Governance System, Section 4: The European Union as an Emerging Federal System, Jean Monnet Center at NYU School of Law

- Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (8 July 2003). "Giscard's 'federal' ruse to protect Blair". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- "The Future of the European Union ECR Statement" (PDF). www.ecrgroup.eu. 8 March 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- Gehrke, Laurenz (29 September 2020). "Italy's Giorgia Meloni elected president of European Conservatives and Reformists". Politico. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- Jennings, F. (1984). The Ambiguous Iroquois Empire: The Covenant Chain Confederation of Indian Tribes with English Colonies from Its Beginnings to the Lancaster Treaty of 1744. United Kingdom: Norton., p.94

- "Startseite". admin.ch. 13 February 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Federal Chancellery - The Swiss Confederation – a brief guide". Bk.admin.ch. 1 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "The Swiss Confederation Institute". The Swiss Confederation Institute. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- CH: Confoederatio Helvetica - Switzerland - Information Archived 30 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Swissworld.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- "On the way to becoming a federal state (1815-1848)". admin.ch. 27 November 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Russia and Belarus form confederation". BBC News. 8 December 1999. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- Romano, Cesare; Alter, Karen; Shany, Yuval (2014). The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication. OUP Oxford. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-19-966068-1.

- Kembayev, Zhenis (2009). Legal Aspects of the Regional Integration Processes in the Post-Soviet Area. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 98, 100–101. ISBN 978-3-540-87652-6.

- Lagutina, Maria (2019). Regional Integration and Future Cooperation Initiatives in the Eurasian Economic Union. IGI Global. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-7998-1952-3.

- O’Reilly, Johnny; Luhn, Alec (17 August 2020). "Belarus protests: Putin threatens to intervene as 200,000 gather to oppose Lukashenko". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- Heinz H. F. Eulau (1941). "Theories of Federalism under the Holy Roman Empire". The American Political Science Review. 35 (4): 643–664. doi:10.2307/1948073. JSTOR 1948073. S2CID 145527513.

Sources

- Miller, Nicholas (2005). "Serbia and Montenegro". Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. Vol. 3. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 529–581. ISBN 9781576078006.