Cool (aesthetic)

Coolness is an aesthetic of attitude, behavior, comportment, appearance and style which is generally admired. Because of the varied and changing connotations of cool, as well as its subjective nature, the word has no single meaning. It has associations of composure and self-control[1] and often is used as an expression of admiration or approval. Although commonly regarded as slang, it is widely used among disparate social groups and has endured in usage for generations.

Overview

There is no single concept of cool. One consistent aspect however, is that cool is widely seen as desirable.[2][3][4] Although there is no single concept of cool, its definitions fall into a few broad categories.

As a behavioral characteristic

The sum and substance of cool is a self-conscious aplomb in overall behavior, which entails a set of specific behavioral characteristics that is firmly anchored in symbology, a set of discernible bodily movements, postures, facial expressions and voice modulations that are acquired and take on strategic social value within the peer context.[4]

Cool was once an attitude fostered by rebels and underdogs, such as slaves, prisoners, bikers and political dissidents, etc., for whom open rebellion invited punishment, so it hid defiance behind a wall of ironic detachment, distancing itself from the source of authority rather than directly confronting it.[5]

In general, coolness is a positive trait based on the inference that a cultural object (e.g., a person or brand) is autonomous in an appropriate way; that is, the person or brand is not constrained by the norms, expectation of beliefs of others.[2]

As a state of being

Cool has been used to describe a general state of well-being, a transcendent, internal state of peace and serenity.[6] It can also refer to an absence of conflict, a state of harmony and balance, as in "The land is cool", or as in a "cool [spiritual] heart". Such meanings, according to Thompson, are African in origin. Cool is related in this sense to both social control and transcendental balance.[6]

Cool can similarly be used to describe composure and absence of excitement in a person—especially in times of stress—as expressed in the idiom "to keep your cool".

In a related way, the word can be used to express agreement or assent, as in the phrase "I'm cool with that".

As aesthetic appeal

Cool is also an attitude widely adopted by artists and intellectuals, who thereby aided its infiltration into popular culture. Sought by product marketing firms, idealized by teenagers, a shield against racial oppression or political persecution and source of constant cultural innovation, cool has become a global phenomenon.[7] Concepts of cool have existed for centuries in several cultures.[8]

As fashion

In terms of fashion, the concept of "cool" has transformed from the 1960s to the 1990s by becoming integrated in the dominant fabric of culture. America's mass-production of "ready-to-wear" fashion in the 1940s and '50s, established specific conventional outfits as markers of ones fixed social role in society. Subcultures such as the Hippies, felt repressed by the dominating conservative ideology of the 1940s and '50s towards conformity and rebelled. According to Dick Pountain's definition of "cool", Hippie's fashionable dress can be seen as "cool" because of its prominent deviation away from the standard uniformity of dress and mass-production of dress, created by the totalitarian system of fashion was seen as "cool".[9] They had various different styles that features bold colors such as the "Trippy Hippie", the "Fantasy Hippie", the "Retro Hippie", the "Ethnic Hippie", and the "Craft Hippie".[10] Additionally, according to the strain theory, Hippies' hand production of their clothing makes them "cool". By naturally hand-making their clothing they rebelled against consumerism in a passive manner because it allowed them to simply not participate in that lifestyle, which makes them "cool", As a result of their disengagement, the scope of self-critique was limited because their mask filtered negative thoughts of worthlessness, fostering the opportunity for self-worth.[9]

Starting in the 1990s and continuing into the 21st century, the concept of "dressing cool" left the minority and went into the mainstream culture, making "dressing cool" a dominant ideology. Cool entered the mainstream because those Hippie "rebels" of the late 1960s were now senior executives of business sectors and of the fashion industry. Since they grew up with "cool" and maintained the same values, they knew its rules and thus knew how to accurately market and produce such clothing.[9] However, once "cool" became the dominant ideology in the 21st century its definition changed to not one of rebellion but of one attempting to hide their insecurities in a confident manner.

The "fashion-grunge" style of the 1990s and 21st century allowed people who felt financially insecure about their lifestyle to pretend to "fit in" by wearing a unique piece of clothing, but one that was polished beautiful. For example, unlike the Hippie style that clearly diverges from the norm, through Marc Jacobs' combined "fashion-grunge" style of "a little preppie, a little grunge and a little couture", he produces not a bold statement one that is mysterious and awkward creating an ambiguous perception of what the wearer's internal feelings are.[11]

As an epithet

While slang terms are usually short-lived coinages and figures of speech, cool is an especially ubiquitous slang word, most notably among young people. As well as being understood throughout the English-speaking world, the word has even entered the vocabulary of several languages other than English.

In this sense, cool is used as a general positive epithet or interjection, which can have a range of related adjectival meanings.

Regions

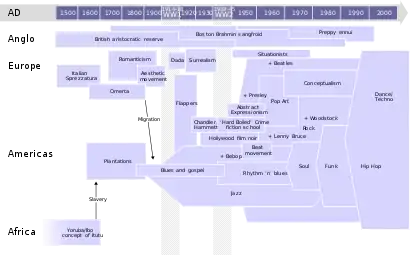

One of the essential characteristics of cool is its mutability—what is considered cool changes over time and varies among cultures and generations.[8]

Africa and the African diaspora

Author Robert Farris Thompson, professor of art history at Yale University, suggests that Itutu, which he translates as "mystic coolness",[12] is one of three pillars of a religious philosophy created in the 15th century[13] by Yoruba and Igbo civilizations of West Africa. Cool, or Itutu, contained meanings of conciliation and gentleness of character, of generosity and grace, and the ability to defuse fights and disputes. It also was associated with physical beauty. In Yoruba culture, Itutu is connected to water, because to the Yoruba the concept of coolness retained its physical connotation of temperature.[14] He cites a definition of cool from the Gola people of Liberia, who define it as the ability to be mentally calm or detached, in an other-worldly fashion, from one's circumstances, to be nonchalant in situations where emotionalism or eagerness would be natural and expected.[6] Joseph M. Murphy writes that "cool" is also closely associated with the deity Òsun of the Yoruba religion.[15]

Although Thompson acknowledges similarities between African and European cool in shared notions of self-control and imperturbability,[14] he finds the cultural value of cool in Africa which influenced the African diaspora to be different from that held by Europeans, who use the term primarily as the ability to remain calm under stress. According to Thompson, there is significant weight, meaning and spirituality attached to cool in traditional African cultures, something which, Thompson argues, is absent from the idea in a Western context.

The telling point is that the "mask" of coolness is worn not only in time of stress, but also of pleasure, in fields of expressive performance and the dance. Struck by the re-occurrence of this vital notion elsewhere in tropical Africa and in the Pan-American African Diaspora, I have come to term the attitude "an aesthetic of the cool" in the sense of a deeply and completely motivated, consciously artistic, interweaving of elements serious and pleasurable, of responsibility and play.[16]

African Americans

Ronald Perry writes that many words and expressions have passed from African-American Vernacular English into Standard English slang including the contemporary meaning of the word "cool".[17] The definition, as something fashionable, is said to have been popularized in jazz circles by tenor saxophonist Lester Young.[18] This predominantly black jazz scene in the U.S. and among expatriate musicians in Paris helped popularize notions of cool in the U.S. in the 1940s, giving birth to "Bohemian", or beatnik, culture.[7] Shortly thereafter, a style of jazz called cool jazz appeared on the music scene, emphasizing a restrained, laid-back solo style.[19] Notions of cool as an expression of centeredness in a Taoist sense, equilibrium and self-possession, of an absence of conflict are commonly understood in both African and African-American contexts well. Expressions such as "Don't blow your cool", or later, "chill out", and the use of "chill" as a characterization of inner contentment or restful repose, all have their origins in African-American Vernacular English.[20]

When the air in the smoke-filled nightclubs of that era became unbreathable, windows and doors were opened to allow some "cool air" in from the outside to help clear away the suffocating air. By analogy, the slow and smooth jazz style that was typical for that late-night scene came to be called "cool".[21]

The purpose of the cool jazz as Giogia stated, "The goal was always the same: to lower the temperature of the music and bring out different qualities in jazz."[22]

Marlene Kim Connor connects cool and the post-war African-American experience in her book What is Cool?: Understanding Black Manhood in America. Connor writes that cool is the silent and knowing rejection of racist oppression, a self-dignified expression of masculinity developed by black men denied mainstream expressions of manhood. She writes that mainstream perception of cool is narrow and distorted, with cool often perceived merely as style or arrogance, rather than a way to achieve respect.[23]

Designer Christian Lacroix has said that "the history of cool in America is the history of African-American culture".[24]

Among black men in America, coolness, which may have its roots in slavery as an ironic submission and concealed subversion (see article by Thorsten Botz-Bornstein),[25] at times is enacted in order to create a powerful appearance, a type of performance frequently maintained for the sake of a social audience.[26]

Cool pose

"Cool", though an amorphous quality—more mystique than material—is a pervasive element in urban black male culture.[27] Majors and Billson address what they term "cool pose" in their study and argue that it helps black men counter stress caused by social oppression, rejection and racism. They also contend that it furnishes the black male with a sense of control, strength, confidence and stability and helps him deal with the closed doors and negative messages of the "generalized other". They also believe that attaining black manhood is filled with pitfalls of discrimination, negative self-image, guilt, shame and fear.[28]

"Cool pose" may be a factor in discrimination in education contributing to the achievement gaps in test scores. In a 2004 study, researchers found that teachers perceived students with African-American culture-related movement styles, referred to as the "cool pose", as lower in achievement, higher in aggression, and more likely to need special education services than students with standard movement styles, irrespective of race or other academic indicators.[29] The issue of stereotyping and discrimination with respect to "cool pose" raises complex questions of assimilation and accommodation of different cultural values. Jason W. Osborne identifies "cool pose" as one of the factors in black underachievement.[30] Robin D. G. Kelley criticizes calls for assimilation and sublimation of black culture, including "cool pose". He argues that media and academics have unfairly demonized these aspects of black culture while, at the same time, through their sustained fascination with blacks as exotic others, appropriated aspects of "cool pose" into the broader popular culture.[31]

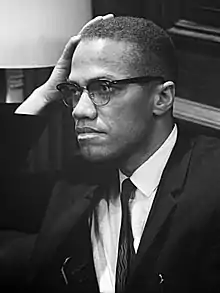

George Elliott Clarke writes that Malcolm X, like Miles Davis, embodies essential elements of cool. As an icon, Malcolm X inspires a complex mixture of both fear and fascination in broader American culture, much like "cool pose" itself.[27]

East Asia

In Japan, synonyms of "cool" could be iki and sui. These are traditional commoners' aesthetic ideals that developed in Edo. Some tend to immediately connect the aesthetics of Japan to samurai, but this is historically inaccurate. In fact, samurais from the countryside have often been the target of ridicule by the commoner in the civilized Edo in many art forms including rakugo, a form of comical storytelling.

Some argue that the ethic of the Samurai caste in Japan, warrior castes in India and East Asia all resemble cool.[8] The samurai-themed works of film director Akira Kurosawa are among the most praised of the genre, influencing many filmmakers across the world with his techniques and storytelling. Notable works of his include The Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, and The Hidden Fortress. The latter was one of the primary inspirations for George Lucas's Star Wars, which also borrows a number of aspects from the samurai, for example the Jedi Knights of the series. Samurai have been presented as cool in many modern Japanese movies such as Samurai Fiction, Kagemusha,[32] and Yojimbo.[33]

In The Art of War, a Chinese military treatise written during the 6th century BC, general Sun Tzu, a member of the landless Chinese aristocracy, wrote in Chapter XII:

Profiting by their panic, we shall exterminate them completely; this will cool the King's courage and cover us with glory, besides ensuring the success of our mission.

Asian countries have developed a tradition on their own to explore types of modern "cool" or "ambiguous" aesthetics.

In a Time Asia article, "The Birth of Cool", author Hannah Beech describes Asian cool as "a revolution in taste led by style gurus who are redefining Chinese craftsmanship in everything from architecture and film to clothing and cuisine" and as a modern aesthetic inspired both by a Ming-era minimalism and a strenuous attention to detail.[34]

Paul Waley, professor of Human Geography at the University of Leeds, considers Tokyo along with New York, London and Paris to be one of the world's "capitals of cool"[35] and The Washington Post called Tokyo "Japan's Empire of Cool" and Japan "the coolest nation on Earth".

Analysts are marveling at the breadth of a recent explosion in cultural exports, and many argue that the international embrace of Japan's pop culture, film, food, style and arts is second only to that of the United States. Business leaders and government officials are now referring to Japan's "gross national cool" as a new engine for economic growth and societal buoyancy.[36]

The term "gross national cool" was coined by journalist Douglas McGray. In a June/July 2002 article in Foreign Policy magazine,[37] he argued that as Japan's economic juggernaut took a wrong turn into a 10-year slump, and with military power made impossible by a pacifist constitution, the nation had quietly emerged as a cultural powerhouse: "From pop music to consumer electronics, architecture to fashion, and food to art, Japan has far greater cultural influence now than it did in the 1980s, when it was an economic superpower."[38] The notion of Asian "cool" applied to Asian consumer electronics is borrowed from the cultural media theorist Eric McLuhan who described "cool" or "cold" media as stimulating participants to complete auditive or visual media content, in sharp contrast to "hot" media that degrades the viewer to a merely passive or non-interactive receiver.

Aristocratic and artistic cool

"Aristocratic cool", known as sprezzatura, has existed in Europe for centuries, particularly when relating to frank amorality and love or illicit pleasures behind closed doors;[8] Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione and Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa are classic examples of sprezzatura.[39] The sprezzatura of the Mona Lisa is seen in both her smile and the positioning of her hands. Both the smile and hands are intended to convey her grandeur, self-confidence and societal position.[40] Sprezzatura means, literally, disdain and detachment. It is the art of refraining from the appearance of trying to present oneself in a particular way. In reality, of course, tremendous exertion went into pretending not to bother or care.

English poet and playwright William Shakespeare used cool in several of his works to describe composure and absence of emotion.[8] In A Midsummer Night's Dream, written sometime in the late-16th century, he contrasts the shaping fantasies of lovers and madmen with "cool reason",[41] in Hamlet he wrote "O gentle son, upon the heat and flame of thy distemper, sprinkle cool patience",[42] and the antagonist Iago in Othello is musing about "reason to cool our raging motions, our carnal stings, our unbitted lusts."[8][43]

The cool "Anatolian smile" of Turkey is used to mask emotions. A similar "mask" of coolness is worn in both times of stress and pleasure in American and African communities.[8]

In The Diary of a Nobody, coolness is used as a criticism: "Upon my word, Gowing's coolness surpasses all belief."

European inter-war cool

The key themes of modern European cool were forged by avant-garde artists who achieved prominence in the aftermath of the First World War, most notably Dadaists, such as key Dada figures Arthur Cravan and Marcel Duchamp, and the left-wing milieu of the Weimar Republic. The program of such groups was often self-consciously revolutionary, a determination to scandalize the bourgeoisie by mocking their culture, sexuality and political moderation.[8]

Berthold Brecht, both a committed Communist and a philandering cynic, stands as the archetype of this inter-war cool. Brecht projected his cool attitude to life onto his most famous character Macheath or "Mackie Messer" (Mack the knife), in The Threepenny Opera. Mackie, the nonchalant, smooth-talking gangster, expert with the switchblade, personifies the bitter-sweet strain of cool; Puritanism and sentimentality are both anathema to the cool character.[8]

During the turbulent inter-war years, cool was a privilege reserved for bohemian milieus like Brecht's. Cool irony and hedonism remained the province of cabaret artistes, ostentatious gangsters and rich socialites, those decadents depicted in Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited and Christopher Isherwood's Goodbye to Berlin, tracing the outlines of a new cool. Peter Stearns, professor of history at George Mason University, suggests that in effect the seeds of a cool outlook had been sown among this inter-war generation.[44]

Post-World War II cool

The Second World War brought the populations of Britain, Germany and France into intimate contact with Americans and American culture. The war brought hundreds of thousands of GIs whose relaxed, easy-going manner was seen by young people of the time as the very embodiment of liberation; and with them came Lucky Strikes, nylons, swing and jazz—the American Cool.

To be cool or hip meant hanging out, pursuing sexual liaisons, displaying the appropriate attitude of narcissistic self-absorption, and expressing a desire to escape the mental straitjacket of all ideological causes. From the late 1940s onward, this popular culture influenced young people all over the world, to the great dismay of the paternalistic elites who still ruled the official culture. The French intelligentsia were outraged, while the British educated classes displayed a haughty indifference that smacked of an older aristocratic cool.[45]

The Polish cool

The new attitude found a special resonance behind the Iron Curtain, where it offered relief from the earnestness of socialist propaganda and socialist realism in art. In the Polish industrial city Łódź, jazz, "the forbidden music", served Polish youth of the 1950s much as it had served its African-American creators, both as personal diversion and subterranean resistance to what they saw as a stultifying official culture. Some clubs featured live jazz performances, and their smoky, sexually charged atmosphere carried a message for which the puritanical values and monumental art of Marxist officialdom were an ideal foil.[46]

Arriving in Poland via France, America and England, Polish cool stimulated the film talents of a generation of artists, including Andrzej Wajda, Roman Polanski, and other graduates of the National Film School in Łódź, as well as the novelist Jerzy Kosinski, in whose clinical prose cool tends towards the sadistic.[8]

Czech cool

In Prague, the capital of Bohemia, cool flourished in the faded Art Deco splendor of the Cafe Slavia. Significantly, following the crushing of the Prague Spring by Soviet tanks in 1968, part of the dissident underground called itself the "Jazz Section".[8]

Theories

As a positive trait

According to this theory, coolness is a subjective, dynamic, socially-constructed trait, such that coolness is in the eye of the beholder. People perceive things (e.g., other people, products or brands) to be cool based on an inference of "autonomy". That is, something is perceived to be cool when it follows its own motivations. However, this theory proposes that the level of autonomy that leads to coolness is constrained – inappropriate levels of autonomy, such that the autonomy is too high or opposes a legitimate norm, do not lead to perceptions of coolness. The level of autonomy considered appropriate is influenced by individual difference variables. For example, people who think of societal institutions and authority as unjust or repressive perceive coolness at higher levels of autonomy than those who are less critical of social norms and authority.[2]

As social distinction

According to this theory, coolness is a relative concept. In other words, cool exists only in comparison with things considered less cool; for example, in the book The Rebel Sell, cool is created out of a need for status and distinction. This creates a situation analogous to an arms race, in which cool is perpetuated by a collective action problem in society.[47]

As an elusive essence

According to this theory, cool is a real, but unknowable property. Cool, like "Good", is a property that exists, but can only be sought after. In the New Yorker article, "The Coolhunt",[48] cool is given three characteristics:

- "The act of discovering what's cool is what causes cool to move on"

- "Cool cannot be manufactured, only observed"

- "[Cool] can only be observed by those who are themselves cool".

As a marketing device

[Cool is] a heavily manipulative corporate ethos.

— Kalle Lasn

Over the past decade, young black men in American inner cities have been the market most aggressively mined by brandmasters as a source of borrowed 'meaning' and identity. .. The truth is that the 'got to be cool' rhetoric of the global brands is, more often than not, an indirect way of saying 'got to be black.'

— Designer Christian Lacroix[24]

According to this theory, cool can be exploited as a manufactured and empty idea imposed on the culture at large through a top-down process by the "Merchants of Cool".[49] The "Merchants of Cool" are sellers of popular culture who capitalize off trends and subcultures, most often created by youths. Some modern examples of the "Merchants of Cool" are record company executives, sneaker and fashion company branders and merchandisers. Furthermore, "cool has become the central ideology of consumer capitalism",[50] the selling of cool thus drives young people and adults attempting to "fit in" to the mainstream and adhere to trends to purchase products and/or brands that make them appear cool.

The concept of cool was used in this way to market menthol cigarettes to African Americans in the 1960s. In 2004, over 70% of African American smokers preferred menthol cigarettes, compared with 30% of white smokers. This unique social phenomenon was principally occasioned by the tobacco industry's manipulation of the burgeoning black, urban, segregated, consumer market in cities at that time. According to Fast Company magazine, some large companies have started "outsourcing cool". They are paying other "smaller, more-limber, closer-to-the-ground outsider" companies to help them keep up with customers' rapidly changing tastes and demands.

Definitions

- "If status is about standing, cool is about standing free"[51] – Grant McCracken

- "Cool is a knowledge, a way of life."[52] – Lewis MacAdams

- "Cool is an age-specific phenomenon, defined as the central behavioural trait of teenagerhood."[53]

- "Coolness is the proper way you represent yourself to a human being."[54] – Robert Farris Thompson

- In the novel Spook Country by William Gibson one character equates cool with a sense of exclusivity: "Secrets," said the Bigend beside her, "are the very root of cool."[55]

- In the novel Lords and Ladies by Terry Pratchett the Monks of Cool are mentioned. In their passing-out test a novice must select the coolest garment from a room full of clothes. The correct answer is "Hey, whatever I select", suggesting that cool is primarily an attitude of self-assurance.[56]

- "Coolness is a subjective and dynamic, socially constructed positive trait attributed to cultural objects (people, brands, products, trends, etc.) inferred to appropriately autonomous."[2]

See also

- African aesthetic

- Avant-garde

- Based

- Cool Britannia

- Cool jazz

- Fad

- Iki

- Itutu

- Jihad Cool

- Sprezzatura

- Square (slang)

References

- "cool" definition, Oxford English Dictionary.

- Warren & Campbell, "What Makes Things Cool? How Autonomy Influences Perceived Coolness". Article by Caleb Warren and Margaret C. Campbell; Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 41, August 2014

- Kerner, Noah and Gene Pressman (2007), Chasing Cool: Standing out in Today's Cluttered Marketplace, New York: Atria.

- Danesi, Marcel (1994). Cool – The Signs and Meanings of Adolescence. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7483-6.

- Pountain, Dick; Robbins, David (2000). Cool Rules. London, England: Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-071-0.

- Thompson, Robert Farris (Autumn 1973). "An Aesthetic of the Cool". African Arts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 7 (1): 40–43, 64–67, 89–91. doi:10.2307/3334749. JSTOR 3334749.

- Coolhunting With Aristotle Welcome to the Hunt. by Nick Southgate, Cogent

- Pountain, Dick; Robins, David (2000). Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude. Reaktion Book Ltd.

- Pountain, Dick (2000). Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude. London: Reaktion.

- Whitley, Lauren D. (2013). Hippie Chic. Boston: MFA Publications.

- "Marc Jacobs". Voguepedia. Archived from the original on 2014-07-19. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- Flash of the Spirit, Random House 1984, ISBN 0-394-72369-4

- The Benin Empire Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Farris Thompson, African Art in Motion, New York, 1979

- Murphy, Joseph, M. and Sanford, Mei-Mei. Òsun Across the Waters: A Yoruba Goddess in Africa and the Americas, p. 2.

- Thompson, Robert Farris. African Arts.

- "African-American English". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- Cool – Online Etymology Dictionary

- Music of the African Diaspora in the Americas

- Margaret Lee, "Out of the Hood and into the News: Borrowed Black Verbal Expressions in a Mainstream Newspaper" (conference paper, University of Georgia, October 1998); cited in Rickford and Rickford, Spoken Soul, 98.

- Marcel Danesi, Cool – The Signs and Meanings of Adolescence, University of Toronto Press, 1994, p. 37.

- Gioia, Ted. "A History of Cool Jazz in 100 Tracks". jazz. jazz. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Conner, Marlene Kim (1995). What Is Cool? Understanding Black Manhood in America. New York: Crown Publishers. Book profile, Education Resources Information Center U.S. Department of Education, Retrieved on 03-01-2007.

- Klein (2000), pp. 73–4. The Christian Lacroix quote is from "Off the Street...", Vogue, April 1994, 337.

- Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten (2010). "What Does it Mean to Be Cool?". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Majors, Richard (1992). Cool Pose: The Dilemma of Black Manhood in America. p. 4.

- Cool Politics: Styles of Honour in Malcolm X and Miles Davis

- Boddie, Jacquelyn Lynette. "Exploring the turn-around Phenomenon Experienced by African American Urban Male Adolescents in High School". Retrieved on 02-26-2007.

- The Effects of African American Movement Styles on Teachers' Perceptions and Reactions Journal article by Scott T. Bridgest, Audrey Davis Mccray, La Vonne I. Neal, Gwendolyn Webb-Johnson; Journal of Special Education, Vol. 37, 2003

- Jason W. Osborne, "Unraveling Underachievement among African American Boys from an Identification with Academics Perspective", The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 68, No. 4 (Autumn 1999), pp. 555–565. doi:10.2307/2668154

- Robin D. G. Kelley, Yo' Mama's Disfunktional!: Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America.

- "Kagemusha". Olive Films. Archived from the original on 2008-04-26. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- "Apollo Movie Guide's Review of Yojimbo". Apolloguide.com. Archived from the original on 2008-01-06. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- Beech, Hannah (2002-11-11). "The Next Cultural Revolution | The Birth of Cool". Time Asia. Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- "GLOCOM Platform – Books & Journals – Journal Abstracts". Glocom.org. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- Faiola, Anthony (2003-12-27). "Japan's Empire of Cool". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- Japan Society Archived October 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Metropolis Tokyo Feature – Pop star". Metropolis.co.jp. Archived from the original on 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- The High Museum Campaign reaches $130 Million Goal Archived September 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Sample text for Becoming Mona Lisa : the making of a global icon / Donald Sassoon.

- William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act V, Scene 1.

- William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark, The Harvard Classics, 1909–14. Act III Scene IV

- William Shakespeare, Othello, Act 1

- Peter N. Stearns, American Cool: Constructing a Twentieth-Century Emotional Style (History of Emotion), New York University Press, 1994.

- Herbert Gold, Bohemia: Digging the Roots of Cool, Touchstone Books; Reprint edition 1994

- James P. Sloan, Jerzy Kosinski: A Biography, Diane Pub. Co., 1996

- Heath, Joseph and Potter, Andrew. The Rebel Sell. Harper Perennial, 2004.

- The Coolhunt Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "Merchants Of Cool". Frontline. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- woden (2016-01-25). "What's in a Word? Telling Your Story with the Right Voice". Medium. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- McCracken, Grant (2009). Chief Culture Officer. P.71: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02204-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "Interview with the Author of Birth of the Cool, Lewis MacAdams". SimonSays.com, Simon & Schuster. Retrieved on 02-27-2007.

- Marcel Dansei, Cool: The Signs and Meanings of Adolescence, p. 1.

- Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit. New York: Vintage Books, 1983, p. 13.

- Gibson, William. Spook Country, Viking, 2007, p. 106.

- Terry Pratchett, Lords and Ladies, Corgi, 2005, p. 244.

Further reading

- Alan Liu (2004). The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information. University of Chicago Press

- Lewis MacAdams (2001). Birth of the Cool: Beat, Bebop, and the American Avant-Garde. New York: Free Press.

- Ted Gioia (2009). The Birth (and Death) of the Cool. Speck Press/Fulcrum Publishing.

- Dick Pountain and David Robins (2000). Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude. Reaktion Books.

- Peter Stearns (1994). American Cool: Constructing a Twentieth-Century Emotional Style. New York University Books.

- John Leland (2004). Hip: The History. Ecco Press

- Jeffries, Michael P. (2011). Thug Life: Race, Gender, and the Meaning of Hip-Hop. University of Chicago Press

- Dinerstein, Joel (2017). The Origins of Cool in Postwar America. University of Chicago Press