Copper conductor

Copper has been used in electrical wiring since the invention of the electromagnet and the telegraph in the 1820s.[1][2] The invention of the telephone in 1876 created further demand for copper wire as an electrical conductor.[3]

Copper is the electrical conductor in many categories of electrical wiring.[3][4] Copper wire is used in power generation, power transmission, power distribution, telecommunications, electronics circuitry, and countless types of electrical equipment.[5] Copper and its alloys are also used to make electrical contacts. Electrical wiring in buildings is the most important market for the copper industry.[6] Roughly half of all copper mined is used to manufacture electrical wire and cable conductors.[5]

Properties of copper

Electrical conductivity

Electrical conductivity is a measure of how well a material transports an electric charge. This is an essential property in electrical wiring systems. Copper has the highest electrical conductivity rating of all non-precious metals: the electrical resistivity of copper = 16.78 nΩ•m at 20 °C.

The theory of metals in their solid state[7] helps to explain the unusually high electrical conductivity of copper. In a copper atom, the outermost 4s energy zone, or conduction band, is only half filled, so many electrons are able to carry electric current. When an electric field is applied to a copper wire, the conduction of electrons accelerates towards the electropositive end, thereby creating a current. These electrons encounter resistance to their passage by colliding with impurity atoms, vacancies, lattice ions, and imperfections. The average distance travelled between collisions, defined as the "mean free path", is inversely proportional to the resistivity of the metal. What is unique about copper is its long mean free path (approximately 100 atomic spacings at room temperature). This mean free path increases rapidly as copper is chilled.[8]

Because of its superior conductivity, annealed copper became the international standard to which all other electrical conductors are compared. In 1913, the International Electrotechnical Commission defined the conductivity of commercially pure copper in its International Annealed Copper Standard, as 100% IACS = 58.0 MS/m at 20 °C, decreasing by 0.393%/°C.[9][10] Because commercial purity has improved over the last century, copper conductors used in building wire often slightly exceed the 100% IACS standard.[11]

The main grade of copper used for electrical applications is electrolytic-tough pitch (ETP) copper (CW004A or ASTM designation C11040). This copper is at least 99.90% pure and has an electrical conductivity of at least 101% IACS. ETP copper contains a small percentage of oxygen (0.02 to 0.04%). If high conductivity copper needs to be welded or brazed or used in a reducing atmosphere, then specially-pure oxygen-free copper (CW008A or ASTM designation C10100) may be used;[12] it is about 1% more conductive (i.e., achieves a minimum of 101% IACS).[9][10]

Several electrically conductive metals are less dense than copper, but require larger cross sections to carry the same current and may not be usable when limited space is a major requirement.[8][4] Aluminium has 61% of the conductivity of copper.[13] The cross sectional area of an aluminium conductor must be 56% larger than copper for the same current carrying capability. The need to increase the thickness of aluminium wire restricts its use in many applications,[4] such as in small motors and automobiles. However, in some applications such as aerial electric power transmission cables, aluminium predominates, and copper is rarely used.

Silver, a precious metal, is the only metal with a higher electrical conductivity than copper. The electrical conductivity of silver is 106% of that of annealed copper on the IACS scale, and the electrical resistivity of silver = 15.9 nΩ•m at 20 °C.[14][15] The high cost of silver combined with its low tensile strength limits its use to special applications, such as joint plating and sliding contact surfaces, and plating for the conductors in high-quality coaxial cables used at frequencies above 30 MHz

Tensile strength

Tensile strength measures the force required to pull an object such as rope, wire, or a structural beam to the point where it breaks. The tensile strength of a material is the maximum amount of tensile stress it can take before breaking.

Copper’s higher tensile strength (200–250 N/mm2 annealed) compared to aluminium (100 N/mm2 for typical conductor alloys[16]) is another reason why copper is used extensively in the building industry. Copper’s high strength resists stretching, neck-down, creep, nicks and breaks, and thereby also prevents failures and service interruptions.[17] Copper is much heavier than aluminum for conductors of equal current carrying capacity, so the high tensile strength is offset by its increased weight.

Ductility

Ductility is a material's ability to deform under tensile stress. This is often characterized by the material's ability to be stretched into a wire. Ductility is especially important in metalworking because materials that crack or break under stress cannot be hammered, rolled, or drawn (drawing is a process that uses tensile forces to stretch metal).

Copper has a higher ductility than alternate metal conductors with the exception of gold and silver.[18] Because of copper’s high ductility, it is easy to draw down to diameters with very close tolerances.[19]

Strength and ductility combination

Usually, the stronger a metal is, the less pliable it is. This is not the case with copper. A unique combination of high strength and high ductility makes copper ideal for wiring systems. At junction boxes and at terminations, for example, copper can be bent, twisted, and pulled without stretching or breaking.[17]

Creep resistance

Creep is the gradual deformation of a material from constant expansions and contractions under “load, no-load” conditions. This process has adverse effects on electrical systems: terminations can become loose, causing connections to heat up or create dangerous arcing.

Copper has excellent creep characteristics that minimizes loosening at connections. For other metal conductors that creep, extra maintenance is required to check terminals periodically and ensure that screws remain tightened to prevent arcing and overheating.[17]

Corrosion resistance

Corrosion is the unwanted breakdown and weakening of a material due to chemical reactions. Copper generally resists corrosion from moisture, humidity, industrial pollution, and other atmospheric influences. However, any corrosion oxides, chlorides, and sulfides that do form on copper are somewhat conductive.[13][17]

Under many application conditions copper is higher on the galvanic series than other common structural metals, meaning that copper wire is less likely to be corroded in wet conditions. However, any more anodic metals in contact with copper will be corroded since they will essentially be sacrificed to the copper.

Coefficient of thermal expansion

Metals and other solid materials expand upon heating and contract upon cooling. This is an undesirable occurrence in electrical systems. Copper has a low coefficient of thermal expansion for an electrical conducting material. Aluminium, an alternate common conductor, expands nearly one third more than copper under increasing temperatures. This higher degree of expansion, along with aluminium’s lower ductility, can cause electrical problems when bolted connections are improperly installed. By using proper hardware, such as spring pressure connections and cupped or split washers at the joint, it may be possible to create aluminium joints that compare in quality to copper joints.[13]

Thermal conductivity

Thermal conductivity is the ability of a material to conduct heat. In electrical systems, high thermal conductivity is important for dissipating waste heat, particularly at terminations and connections. Copper has a 60% higher thermal conductivity rating than aluminium,[17] so it is better able to reduce thermal hot spots in electrical wiring systems.[8][20]

Solderability

Soldering is a process whereby two or more metals are joined together by a heating process. This is a desirable property in electrical systems. Copper is readily soldered to make durable connections when necessary.

Ease of installation

The strength, hardness, and flexibility of copper make it very easy to work with. Copper wiring can be installed simply and easily with no special tools, washers, pigtails, or joint compounds. Its flexibility makes it easy to join, while its hardness helps keep connections securely in place. It has good strength for pulling wire through tight places (“pull-through”), including conduits. It can be bent or twisted easily without breaking. It can be stripped and terminated during installation or service with far less danger of nicks or breaks. And it can be connected without the use of special lugs and fittings. The combination of all of these factors makes it easy for electricians to install copper wire.[17][21]

Types

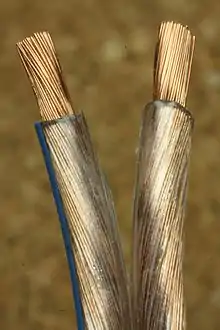

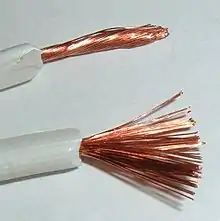

Solid and stranded

Solid wire consists of one strand of copper metal wire, bare or surrounded by an insulator. Single-strand copper conductors are typically used as magnet wire in motors and transformers. They are relatively rigid, do not bend easily, and are typically installed in permanent, infrequently handled, and low flex applications.

Stranded wire has a group of copper wires braided or twisted together. Stranded wire is more flexible and easier to install than a large single-strand wire of the same cross section. Stranding improves wire life in applications with vibration. A particular cross-section of a stranded conductor gives it essentially the same resistance characteristics as a single-strand conductor, but with added flexibility.[22]

Cable

A copper cable consists of two or more copper wires running side by side and bonded, twisted or braided together to form a single assembly. Electrical cables may be made more flexible by stranding the wires.

Copper wires in a cable may be bare or they may be plated to reduce oxidation with a thin layer of another metal, most often tin but sometimes gold or silver. Plating may lengthen wire life and makes soldering easier. Twisted pair and coaxial cables are designed to inhibit electromagnetic interference, prevent radiation of signals, and to provide transmission lines with defined characteristics. Shielded cables are encased in foil or wire mesh.

Applications

Electrolytic-tough pitch (ETP) copper, a high-purity copper that contains oxygen as an alloying agent, represents the bulk of electrical conductor applications because of its high electrical conductivity and improved annealability. ETP copper is used for power transmission, power distribution, and telecommunications.[5] Common applications include building wire, motor windings, electrical cables, and busbars. Oxygen-free coppers are used to resist hydrogen embrittlement when extensive amounts of cold work is needed, and for applications requiring higher ductility (e.g., telecommunications cable). When hydrogen embrittlement is a concern and low electrical resistivity is not required, phosphorus may be added to copper.[8]

For certain applications, copper alloy conductors are preferred instead of pure copper, especially when higher strengths or improved abrasion and corrosion resistance properties are required. However, relative to pure copper, the higher strength and corrosion resistance benefits that are offered by copper alloys are offset by their lower electrical conductivities. Design engineers weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the various types of copper and copper alloy conductors when determining which type to specify for a specific electrical application. An example of a copper alloy conductor is cadmium copper wire, which is used for railroad electrification in North America.[5] In Britain the BPO (later Post Office Telecommunications) used cadmium copper aerial lines with 1% cadmium for extra strength; for local lines 40 lb/mile (1.3 mm dia) and for toll lines 70 lb/mile (1.7 mm dia).[23]

Some of the major application markets for copper conductors are summarized below.

Electrical wiring

Electrical wiring distributes electric power inside residential, commercial, or industrial buildings, mobile homes, recreational vehicles, boats, and substations at voltages up to 600 V. The thickness of the wire is based on electric current requirements in conjunction with safe operating temperatures. Solid wire is used for smaller diameters; thicker diameters are stranded to provide flexibility. Conductor types include non-metallic/non-metallic corrosion-resistant cable (two or more insulated conductors with a nonmetallic outer sheath), armored or BX cable (cables are surrounded by a flexible metal enclosure), metal clad cable, service entrance cable, underground feeder cable, TC cable, fire resistant cable, and mineral insulated cable, including mineral-insulated copper-clad cable.[24] Copper is commonly used for building wire because of its conductivity, strength, and reliability. Over the life of a building wire system, copper can also be the most economical conductor.

Copper used in building wire has a conductivity rating of 100% IACS[10][25] or better. Copper building wire requires less insulation and can be installed in smaller conduits than when lower-conductivity conductors are used. Also, comparatively, more copper wire can fit in a given conduit than conductors with lower conductivities. This greater “wire fill” is a special advantage when a system is rewired or expanded.[17]

Copper building wire is compatible with brass and quality plated screws. The wire provides connections that will not corrode or creep. It is not, however, compatible with aluminium wire or connectors. If the two metals are joined, a galvanic reaction can occur. Anodic corrosion during the reaction can disintegrate the aluminium. This is why most appliance and electrical equipment manufacturers use copper lead wires for connections to building wiring systems.[21]

"All-copper" building wiring refers to buildings in which the inside electrical service is carried exclusively over copper wiring. In all-copper homes, copper conductors are used in circuit breaker panels, branch circuit wiring (to outlets, switches, lighting fixtures and the like), and in dedicated branches serving heavy-load appliances (such as ranges, ovens, clothes dryers and air conditioners).[26]

Attempts to replace copper with aluminium in building wire were curtailed in most countries when it was found that aluminium connections gradually loosened due to their inherent slow creep, combined with the high resistivity and heat generation of aluminium oxidation at joints. Spring-loaded contacts have largely alleviated this problem with aluminium conductors in building wire, but some building codes still forbid the use of aluminium.

For branch-circuit sizes, virtually all basic wiring for lights, outlets and switches is made from copper.[17] The market for aluminium building wire today is mostly confined to larger gauge sizes used in supply circuits.[27]

Electrical wiring codes give the allowable current rating for standard sizes of conductors. The current rating of a conductor varies depending on the size, allowable maximum temperature, and the operating environment of the conductor. Conductors used in areas where cool air is free to circulate around the wires are generally permitted to carry more current than the small sized conductor encased in an underground conduit run with many similar conductors adjacent to it. The practical temperature ratings of insulated copper conductors are mostly due to the limitations of the insulation material or of the temperature rating of the attached equipment.

Twisted pair cable

Twisted pair cabling is the most popular network cable and is often used in data networks for short and medium length connections (up to 100 meters or 328 feet).[28] This is due to its relatively lower costs compared to optical fiber and coaxial cable.

Unshielded twisted pair (UTP) cables are the primary cable type for telephone usage. In the late 20th century, UTPs emerged as the most common cable in computer networking cables, especially as patch cables or temporary network connections.[29] They are increasingly used in video applications, primarily in security cameras.

UTP plenum cables that run above ceilings and inside walls use a solid copper core for each conductor, which enables the cable to hold its shape when bent. Patch cables, which connect computers to wall plates, use stranded copper wire because they are expected to be flexed during their lifetimes.[28]

UTPs are the best balanced line wires available. However they are the easiest to tap into. When interference and security are concerns, shielded cable or fiber optic cable is often considered.[28]

UTP cables include: Category 3 cable, now the minimum requirement by the FCC (USA) for every telephone connection; Category 5e cable, 100-MHz enhanced pairs for running Gigabit Ethernet (1000Base-T); and Category 6 cable, where each pair runs 250 MHz for improved 1000Base-T performance.[29][30]

In copper twisted pair wire networks, copper cable certification is achieved through a thorough series of tests in accordance with Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA) or International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards.

Coaxial cable

Coaxial cables were extensively used in mainframe computer systems and were the first type of major cable used for Local Area Networks (LAN). Common applications for coaxial cable today include computer network (Internet) and instrumentation data connections, video and CATV distribution, RF and microwave transmission, and feedlines connecting radio transmitters and receivers with their antennas.[31]

While coaxial cables can go longer distances and have better protection from EMI than twisted pairs, coaxial cables are harder to work with and more difficult to run from offices to the wiring closet. For these reasons, it is now generally being replaced with less expensive UTP cables or by fiber optic cables for more capacity.[28]

Today, many CATV companies still use coaxial cables into homes. These cables, however, are increasingly connected to a fiber optic data communications system outside of the home. Most building management systems use proprietary copper cabling, as do paging/audio speaker systems. Security monitoring and entry systems still often depend on copper, although fiber cables are also used.[32]

Structured wiring

Most telephone lines can share voice and data simultaneously. Pre-digital quad telephone wiring in homes is unable to handle communications needs for multiple phone lines, Internet service, video communications, data transmission, fax machines, and security services. Crosstalk, static interference, inaudible signals, and interrupted service are common problems with outdated wiring. Computers connected to old-fashioned communications wiring often experience poor Internet performance.

“Structured wiring” is the general term for 21st century On-premises wiring for high-capacity telephone, video, data-transmission, security, control, and entertainment systems. Installations usually include a central distribution panel where all connections are made, as well as outlets with dedicated connections for phone, data, TV and audio jacks.

Structured wiring enables computers to communicate with each other error-free and at high speeds while resisting interference among various electrical sources, such as household appliances and external communications signals. Networked computers are able to share high-speed Internet connections simultaneously. Structured wiring can also connect computers with printers, scanners, telephones, fax machines, and even home security systems and home entertainment equipment.

Quad-shielded RG-6 coaxial cable can carry a large number of TV channels at the same time. A star wiring pattern, where the wiring to each jack extends to a central distribution device, facilitates flexibility of services, problem identification, and better signal quality. This pattern has advantages to daisy chain loops. Installation tools, tips, and techniques for networked wiring systems using twisted pairs, coaxial cables, and connectors for each are available.[33][34]

Structured wiring competes with wireless systems in homes. While wireless systems certainly have convenience advantages, they also have drawbacks over copper-wired systems: the higher bandwidth of systems using Category 5e wiring typically support more than ten times the speeds of wireless systems for faster data applications and more channels for video applications. Alternatively, wireless systems are a security risk as they can transmit sensitive information to unintended users over similar receiver devices. Wireless systems are more susceptible to interference from other devices and systems, which can compromise performance.[35] Certain geographic areas and some buildings may be unsuitable for wireless installations, just as some buildings may present difficulties installing wires.

Power distribution

Power distribution is the final stage in the delivery of electricity for an end use. A power distribution system carries electricity from the transmission system to consumers.

Power cables are used for the transmission and distribution of electric power, either outdoors or inside buildings. Details on the various types of power cables are available.[36]

Copper is the preferred conductor material for underground transmission lines operating at high and extra-high voltages to 400 kV. The predominance of copper underground systems stems from its higher volumetric electrical and thermal conductivities compared to other conductors. These beneficial properties for copper conductors conserve space, minimize power loss, and maintain lower cable temperatures.

Copper continues to dominate low-voltage lines in mines and underwater applications, as well as in electric railroads, hoists, and other outdoor services.[5]

Aluminium, either alone or reinforced with steel, is the preferred conductor for overhead transmission lines due to its lighter weight and lower cost.[5]

Appliance conductors

Appliance conductors for domestic applications and instruments are manufactured from bunch-stranded soft wire, which may be tinned for soldering or phase identification. Depending upon loads, insulation can be PVC, neoprene, ethylene propylene, polypropylene filler, or cotton.[5]

Automotive conductors

Automotive conductors require insulation that is resistant to elevated temperatures, petroleum products, humidity, fire, and chemicals. PVC, neoprene, and polyethylene are the most common insulators. Potentials range from 12 V for electrical systems to between 300 V - 15,000 V for instruments, lighting, and ignition systems.[36]

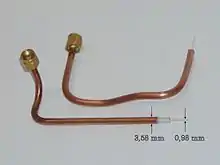

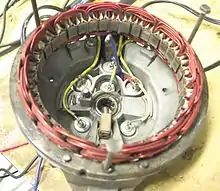

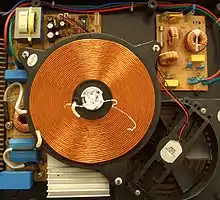

Magnet wire

Magnet wire or winding wire is used in windings of electric motors, transformers, inductors, generators, headphones, loudspeaker coils, hard drive head positioners, electromagnets, and other devices.[5][8]

Most often, magnetic wire is composed of fully annealed, electrolytically refined copper to allow closer winding when making electromagnetic coils. The wire is coated with a range of polymeric insulations, including varnish, rather than the thicker plastic or other types of insulation commonly used on electrical wire.[5] High-purity oxygen-free copper grades are used for high-temperature applications in reducing atmospheres or in motors or generators cooled by hydrogen gas.

Splice closures for copper cables

A copper splice closure is defined as an enclosure, and the associated hardware, that is intended to restore the mechanical and environmental integrity of one or more copper cables entering the enclosure and providing some internal function for splicing, termination, or interconnection.[37]

Types of closures

As stated in Telcordia industry requirements document GR-3151, there are two principal configurations for closures: butt closures and in-line closures. Butt closures permit cables to enter the closure from one end only. This design may also be referred to as a dome closure. These closures can be used in a variety of applications, including branch splicing. In-line closures provide for the entry of cables at both ends of the closure. They can be used in a variety of applications, including branch splicing and cable access. In-line closures can also be used in a butt configuration by restricting cable access to one end of the closure.

A copper splice closure is defined by the functional design characteristics and, for the most part, is independent of specific deployment environments or applications. At this time, Telcordia has identified two types of copper closures:

- Environmentally Sealed Closures (ESCs)

- Free-Breathing Closures (FBCs)

ESCs provide all of the features and functions expected of a typical splice closure in an enclosure that prevents the intrusion of liquid and vapor into the closure interior. This is accomplished through the use of an environmental sealing system such as rubber gaskets or hot-melt adhesives. Some ESCs use pressurized air to help keep moisture out of the closure.

FBCs provide all of the features and functions expected of a typical splice closure that prevents the intrusion of wind-driven rain, dust, and insects. Such a closure, however, permits the free exchange of air with the outside environment. Therefore, it is possible that condensation will form inside the closure. It is thus necessary to provide adequate drainage to prevent the accumulation of water inside the closure.

Future trends

Copper will continue to be the predominant material in most electrical wire applications, especially where space considerations are important.[3] The automotive industry for decades has considered the use of smaller-diameter wires in certain applications. Many manufacturers are beginning to use copper alloys such as copper-magnesium (CuMg), which allow for smaller diameter wires with less weight and improved conductivity performance. Special alloys like copper-magnesium are beginning to see increased usage in automotive, aerospace, and defense applications.[38]

Due to the need to increase the transmission of high-speed voice and data signals, the surface quality of copper wire is expected to continue to improve. Demands for better drawability and movement towards “zero” defects in copper conductors are expected to continue.

A minimum mechanical strength requirement for magnet wire may evolve in order to improve formability and prevent excessive stretching of wire during high speed coiling operations.

It does not seem likely that standards for copper wire purity will increase beyond the current minimum value of 101% IACS. Although 6-nines copper (99.9999% pure) has been produced in small quantities, it is extremely expensive and probably unnecessary for most commercial applications such as magnet, telecommunications, and building wire. The electrical conductivity of 6-nines copper and 4-nines copper (99.99% pure) is nearly the same at ambient temperature, although the higher-purity copper has a higher conductivity at cryogenic temperatures. Therefore, for non-cryogenic temperatures, 4-nines copper will probably remain the dominant material for most commercial wire applications.[3]

Theft

During the 2000s commodities boom, copper prices increased worldwide,[39] increasing the incentive for criminals to steal copper from power supply and communications cables.[40][41][42]

See also

- Magnet wire

- Annealing by short circuit

- Copper cable certification

- Copper sulfide

- Copper-clad aluminium wire

- Copper-clad steel

- Galvanization

- Mineral-insulated copper-clad cable

- Passivation (chemistry)

- Solderability

References

- Sturgeon, W., 1825, Improved Electro Magnetic Apparatus, Trans. Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures, & Commerce (London) 43: pp. 37–52, as cited in Miller, T.J.E, 2001, Electronic Control of Switched Reluctance Machines, Newnes, p. 7. ISBN 0-7506-5073-7

- Windelspecht, Michael, 2003, Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 19th Century, XXII, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-31969-3

- Pops, Horace, 2008, Processing of wire from antiquity to the future, Wire Journal International, June, pp 58-66

- "The Metallurgy of Copper Wire" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-01. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- Joseph, Günter, 1999, Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status, edited by Kundig, Konrad J.A., ASM International Vol. 2.03, Electrical Conductors

- "Copper, Chemical Element - Overview, Discovery and naming, Physical properties, Chemical properties, Occurrence in nature, Isotopes". Chemistryexplained.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Mott, N.F. and Jones, H., 1958, The theory of the properties of metals and alloys, Dover Publications

- Pops, Horace, 1995, Physical Metallurgy of Electrical Conductors, in Nonferrous Wire Handbook, Volume 3: Principles and Practice, The Wire Association International, pp. 7-22

- "The International Annealed Copper Standard; NDT Resources Center". Ndt-ed.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- Copper Wire Tables; Circular of the Bureau of Standards; No. 31; S. W. Stratton, Director; U.S. Department of Commerce; 1914

- Copper Building Wire Systems Archived 2013-05-24 at the Wayback Machine, Copper Development Association, Inc.

- "Copper — Properties and Applications". Copperinfo.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-07-20. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "VTI : Aluminum vs. Copper: Conductors in Low Voltage Dry Type Transformers". Vt-inc.com. 2006-08-29. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Weast, Robert C. & Shelby, Samuel M. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 48th edition, Ohio: The Chemical Rubber Co. 1967–1968: F-132

- W.F. Gale; T.C. Totemeir, eds. (2004), Smithells Metals Reference Book (8th ed.), Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann Co. and ASM International, ISBN 0-7506-7509-8

- "Development of Aluminum Alloy Conductor with High Electrical Conductivity and Controlled Tensile Strength and Elongation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- "Electrical: Building Wire - Copper Building Wire Systems". Copper.org. 2010-08-25. Archived from the original on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Rich, Jack C., 1988, The Materials and Methods of Sculpture. Courier Dover Publications. p. 129. ISBN 0-486-25742-8, https://books.google.com/?id=hW13qhOFa7gC

- Nonferrous Wire Handbook, Volume 3: Principles and Practice, The Wire Association International

- Pops, Horace; Importance of the conductor and control of its properties for magnet wire applications, in Nonferrous Wire Handbook, Volume 3: Principles and Practice, The Wire Association International, pp 37-52

- "Electrical: Building Wire - Copper, The Best Buy". Copper.org. 2010-08-25. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Wire Wisdom: Choosing Conductors" (PDF). Anixter. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-09. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Telephony by T.E. Herbert & W.S. Procter,Volume 1 p1110 (1946, Pitman, London)

- Copper Building Wire, Copper/Brass/Bronze Products Handbook, CDA Publication 601/0, Copper Development Association

- The International Annealed Copper Standard; NDT Resources Center; "IACS". Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- "Applications: Telecommunications - All-Copper Wiring". Copper.org. 2010-08-25. Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Davis, Joseph R., Copper and copper alloys, ASM International. Handbook Committee, pp. 155-156

- "Network+, Module 3 - The Physical Network". Lrgnetworks.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Selecting coax and twisted-pair cable". .electronicproducts.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "The Evolution of Copper Cabling Systems from Cat5 to Cat5e to Cat6" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-14.www.panduit.com

- Van Der Burgt, Martin J., 2011, "Coaxial Cables and Applications". Belden. p. 4. Retrieved 11 July 2011, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-11. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Applications: Telecommunications - Communications Wiring for Today's Homes". Copper.org. 2010-08-25. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Applications: Telecommunications - Infrastructure Wiring for Homes". Copper.org. 2010-08-25. Archived from the original on 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Structured wiring for today’s homes (CD-ROM), Copper Development Association, NY, NY, USA

- Electric Wire and Cable, brochure 0001240, Cobre Cerrillos S.A., Santiago, Chile; Cocessa Technical Bulletin, Electrical Conductor Catalog 751, MADECO, 1990

- GR-3151-CORE, Generic Requirements for Copper Splice Closures, Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Telcordia.

- "C18661 Copper-Magnesium (CMG1) Alloy Wire". Fisk (website). Fisk Alloy, Inc. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- "Historical Copper Prices, Copper Prices History". Dow-futures.net. 22 January 2007. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Berinato, Scott (2007-02-01). "Copper Theft: The Metal Theft Epidemic". CSO Online. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- "Copper Theft Threatens U.S. Critical Infrastructure". Federal Bureau of Investigation. 15 September 2005. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "4 House Fires and Hundreds of Homes Without Power after Substation Targeted". metaltheftscotland.org.uk. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.