Quercus suber

Quercus suber, commonly called the cork oak, is a medium-sized, evergreen oak tree in the section Quercus sect. Cerris. It is the primary source of cork for wine bottle stoppers and other uses, such as cork flooring and as the cores of cricket balls. It is native to southwest Europe and northwest Africa. In the Mediterranean basin the tree is an ancient species with fossil remnants dating back to the Tertiary period.[3]

| Cork oak | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Cork oak in its natural habitat | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Subgenus: | Quercus subg. Quercus |

| Section: | Quercus sect. Cerris |

| Species: | Q. suber |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus suber | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

It endures drought and makes little demand on the soil quality. Cork oak forests are home to a multitude of animal and plant species. Since cork is increasingly being displaced by other materials as a bottle cap, these forests are at risk as part of the cultural landscape and animal species such as the Iberian lynx are threatened with extinction.[4]

Description

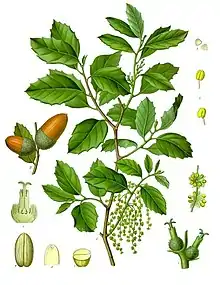

General appearance and bark

The cork oak grows as an evergreen tree, reaching an average height of 10 to 15 metres (33 to 49 feet) or in rare cases up to 25 m and a trunk diameter (DBH) of 50 to 90 centimetres (20 to 35 inches). It forms a dense and asymmetrical crown that starts at a height of 2–3 m (6+1⁄2–10 ft) and spreads widely in free-standing trees. The crown can be divided into several separate, rounded partial crowns.[5][6]

The young twigs are densely hairy light gray or whitish. Older branches are strong and knotty. Older trees only form short shoots between 7 to 15 cm (3 to 6 in) in length.[5]

The thick, longitudinally cracked cork layers of the gray-brown trunk bark are characteristic of the cork oak. The cambium of the smooth bark of young trees forms a cork layer very early on, which can be 3 to 5 cm (1+1⁄4 to 2 in) thick. The light and spongy cork fabric shows vertical cracks and is white on the outside and red to red-brown on the inside. After the cork has been harvested, the trunk appears reddish brown, but later it is significantly darker.[5] The wood is ring-pored, has a brown heartwood and a light reddish sapwood.[7] The cork oak develops a taproot that reaches a depth of 1 to 2 m (3+1⁄4 to 6+1⁄2 ft) and from which several meters long, horizontally running side roots extend.[8] The trees can reach over 400 years old, and harvested specimens can be 150 to 200 years old.[5][6]

Leaves

The leathery leaves are alternate and are 2.5 to 10 cm (1 to 4 in) long and 1.2 to 6.5 cm (1⁄2 to 2+1⁄2 in) wide. The shape varies between round, oval and lanceolate-oval. The leaf blade has five to seven sharp teeth on both edges and a pointed vegetation cone (apex). The midrib stands out clearly on the underside of the leaf, the first-order lateral nerves usually lead to the teeth of the leaf margin. The upper side of the leaf is light green, the underside of the leaf whitish and densely hairy. There is no hair on young trees. The leaf stalks are 6 to 18 millimetres (1⁄4 to 3⁄4 in) long and are also hairy. At the base of the petiole are two narrow, lanceolate, 5 mm (1⁄4 in) long and bright red stipules that fall off in the first year. The new leaves appear in April and May, when older leaves are also shed. They usually stay on the tree for two to three years, less often only one year, the latter especially in severe environmental conditions and on the northern border of the distribution area. Extremely cold winters can also lead to complete defoliation.[5]

Inflorescence and flower

The cork oak is single sexed (monoecious), with both female and male flowers on one specimen.[5] The female flowers form upright inflorescences in the leaf axils of young branches. These are formed from a hairy axis 5 to 30 mm (1⁄4 to 1+1⁄4 in) long with two to five separate flowers. The female flowers contain a small, hairy, four- to six-lobed flower envelope and three to four styles.[8] The male catkins also arise on the leaf axils of young branches. They are bright red at the beginning and stand upright, older catkins are yellow and pendulous, 4 to 7 cm (1+1⁄2 to 2+3⁄4 in) long and have a whitish hairy axis. The single flowers are sessile and have a densely hairy flower cover that is colored red when opened. The four to six stamens are whitish with yellow, egg-shaped anthers. They are longer than the bracts.[5]

Infructescence, fruit and seed

The fruit clusters are 0.5 to 4 cm (1⁄4 to 1+1⁄2 in) long and carry two to eight acorns. About half of the fruits are enclosed in the fruit cup (cupule); the fruit cups are 2 to 2.5 cm (3⁄4 to 1 in) in diameter. The upper scales of the cupula are gray and hairy, in the subspecies Quercus suber occidentalis the scales are close together or are fused. The size of the acorns varies between lengths of 2 to 4.5 cm (3⁄4 to 1+3⁄4 in) and diameters of 1 to 1.8 cm (1⁄2 to 3⁄4 in). The fruit casing (pericarp) is bare, smooth and shiny brownish red. The hilum (the starting point of the seed) is convex and has a diameter of 6 to 8 mm (1⁄4 to 3⁄8 in).[8]

Leaves

Leaves Leaf, front and back

Leaf, front and back Acorn with fruit cup

Acorn with fruit cup Seeds

Seeds Unharvested trunk

Unharvested trunk.jpg.webp) Denuded trunk

Denuded trunk Contrast between old and new cambium

Contrast between old and new cambium

Taxonomy

Quercus suber is a species of the Cerris section to which, for example, the following species also belong:

- Valonia oak (Quercus macrolepis)

- Turkey oak (Quercus cerris)

- Quercus × crenata

- Macedonian oak (Quercus trojana)

Characteristic for the section are the hairless pericarp and the usually two-year ripening time of the fruits. The cork oak is an exception because the fruits can ripen in both the first and the second year.[9]

In the species Quercus suber two subspecies are distinguished:

- Quercus suber subsp. suber: Nominal taxon

- Quercus suber subsp. occidentalis(Gay) Bonnier & Layens: It differs from the nominate form in the shape of the cupula scales, the longer development time of the fruits and the semi-evergreen foliage. The distribution area of the subspecies is the Portuguese Atlantic coast.[9]

Together with the Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) and the holm oak (Quercus ilex), the cork oak forms hybrid bastards.[7]

The scientific name Quercus suber is derived from the Latin word quercus, which the Romans used to describe the pedunculate oak (Quercus robur). The specific epithet suber means in Latin cork oak and also cork.[10]

Distribution and habitat

The cork oak occupies the area around the western Mediterranean basin. In Portugal, natural and cultivated stands cover an area of 750,000 hectares.[9][11] There are natural populations of the nominate form at altitudes between 150 to 300 m (490 to 980 ft) above sea level, the subspecies occidentalis is found along the Atlantic coast. In Spain the occurrences remain mostly below 600 m (2,000 ft), but rarely reach heights of 1,200 m (3,900 ft). In Spain, cork oaks are common in the southern half of the country, as well as in the western and northeastern areas, but rare in central Spain. In Italy one finds natural occurrences along the Tyrrhenian Sea and in eastern Apulia on the Adriatic Sea. Also on the Adriatic is the cork oak on the Dalmatian coast. It is one of the most common forest trees in Sardinia. Natural and man-made occurrences exist in Africa on the Mediterranean coast of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco and at altitudes up to 1,000 m (3,300 ft), on the High Atlas up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[9] In its native range, cork oak forests cover approximately 22,000 square kilometres (8,500 square miles).[1] Outside of its natural range, the cork oak is cultivated in the Crimea, the Caucasus, India and the Southwestern United States.[12] The subspecies Quercus suber occidentalis also thrives in mild areas of England.

The species needs very little light and cannot survive in dense populations. It loves warmth, grows at annual mean temperatures of 13 to 17 °C (55 to 63 °F) and can withstand maximum temperatures of up to 40 °C (104 °F). In the area of distribution, the temperature rarely falls below freezing point, but temperatures down to −5 °C (23 °F) without damage and down to −10 °C (14 °F) without major damage can be tolerated. The cork oak is not hardy in Central Europe. It endures drought and survives dry periods in summer by reducing its metabolism. An annual rainfall of 500 to 700 millimetres (20 to 28 in) is considered optimal, in cooler locations 400 to 450 millimetres (16 to 18 in) can be sufficient with enough humidity. Cork oaks have low soil demands and also grow in poor, dry or rocky locations. They rarely thrive on calcareous soils, but they are often found on crystalline slates, on gneiss, granite and sands. The acidity of the soil should be between pH 4.5 and 7.[13]

The cork oak is considered a pyrophyte because it recovers quickly after forest fires as it is protected by the cork.

Ecology

The cork oak forest is one of the major plant communities of the Mediterranean woodlands and forests ecoregion.[14] In natural populations, the cork oak grows together with the holm oaks (Quercus ilex, Quercus rotundifolia), the downy oak (Quercus pubescens), the maritime pine (Pinus pinaster), the stone pine (Pinus pinea), the strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) and the olive tree (Olea europaea), in cooler locations also with the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa). In addition to these tree species, the shrub-forming species include the Kermes oak (Quercus coccifera), the holly buckthorn (Rhamnus alaternus), species of the genus Phillyrea, the myrtle (Myrtus communis), the green heather (Erica scoparia), the common smilax (Smilax aspera) and the Montpellier cistus (Cistus monspeliensis) are often found together with the cork oak.[13]

Cork oak forests are home to several rare species, such as the Iberian Peninsula for the threatened Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus)[15][16] and the endangered Iberian imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti),[17] and a large part of the European crane population winters here. In the northwestern Maghreb, some cork oak forests are habitat to the endangered Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus), a species whose habitat is fragmented and whose range was prehistorically much wider.[18] The Berber deer (Cervus elaphus subsp. Barbarus) lives in the cork oak forests of Tunisia.[4]

As a pyrophyte, this tree has a thick, insulating bark that makes it well adapted to forest fires.[1] After a fire, many tree species regenerate from seeds (as, for example, the maritime pine) or resprout from the base of the tree (as, for example, the holm oak). The bark of the cork oak allows it to survive fires and then simply regrow branches to fill out the canopy. The quick regeneration of this oak makes it successful in the fire-adapted ecosystems of the Mediterranean biome.[16]

Symbiosis

The cork oak enters into a mycorrhizal symbiosis with several types of fungus. The fine root system of the oak is in close contact with the mycelium of the fungus. The oak receives water and nutrient salts from the fungus in exchange for products of photosynthesis. Such a symbiosis exists among others with the following species:[8]

Diseases and predators

Cork oak is relatively resistant to pathogens, but some diseases occur in the species. Leaf spot can be caused by the fungus Apiognomonia errabunda. Other fungi can cause leaf scorching, powdery mildew, rust, and cankers.[19]

The most virulent cork oak pathogen may be Diplodia corticola, a sac fungus which causes sap-bleeding sunken canker wounds in the wood, withering of the leaves, and lesions on the acorns. The fungus Biscogniauxia mediterranea is becoming more common in cork oak forests. Its fruiting bodies appear as charcoal-black cankers. Both of these fungi are transmitted by the oak pinhole borer (Platypus cylindrus), a species of weevil.[19]

The common water mould Phytophthora cinnamomi grows in the roots of the tree and has been known to devastate cork oak woodlands.[19]

Several species of butterflies damage the cork oak, the most important being the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar). The species lays its eggs in the bark of the branches and trunks, and the caterpillars that hatch in spring are distributed in the crown and eat them bare. The bacterial species Bacillus thuringiensis is used as a biological plant protection agent against the gypsy moth. Another pest is the green oak tortrix (Tortrix viridana), whose caterpillars eat flowers and young leaves and roll them up with thread to form typical coils. The lackey moth (Malacosoma neustria) also causes damage to the leaves, sticking its eggs to the bark of thin twigs in multiple rows, and also the brown-tail moth (Euproctis chrysorrhoea), whose caterpillars skeletonize the leaves and further damage the tree after overwintering in spring. A special cork pest is the jewel beetle Coraebus undatus, which lays its eggs in the cork tissue. Another harmful species of beetle is the great capricorn beetle (Cerambyx cerdo), whose larvae eat long corridors in the oak wood.[20]

Unfavorable climatic conditions and fungal attack are made responsible for the weakening of trees and for crown damage. Such fungal parasites of weakness are Botryosphaeria stevensii, Biscogniauxia mediterranea, Endothiella gyrosa and representatives of the mold genus Fusarium. Drought and parasite infestation are also considered to be the cause of the weakness syndrome in parts of Spain and Portugal.[20]

Uses

The cork oak is grown for the production of cork in several Mediterranean countries. The centers of cork production are in southern Portugal (accounting for 50% of the total production[11]) and southern Spain, where low trees with large crowns and strong branches are grown in large areas, which provide the highest yield of cork.[21] These mostly extensively managed habitats are called montados in Portugal and dehesas in Spain.[22] They are considered to be extremely valuable from the point of view of biodiversity and cultural heritage.[23]

The cork consists of dead, air-filled, thin-walled cells and contains cellulose and suberin. Cork is heat and sound insulating, the suberine gives it water-repellent properties. The cork layer is replicated by the cork-producing phellogen and can therefore be harvested repeatedly without damaging the tree too much. The first harvest usually takes place after about 25 years with a trunk diameter (DBH) of 70 cm (28 in), though new techniques (such as better irrigation systems) could shorten it to only 8 to 10 years.[24][1] The first cork layer is called “male cork” or “virgin cork”, is still not very elastic and cracked and is only used for insulating mats. The second harvested cork (known as secundeira), has a more regular structure and is softer, but is still only used for insulation and in decorative objects.[24] Only the following cork harvests deliver a higher quality cork, the "female cork", which can be used commercially in full. The best quality cork is obtained from the third and fourth harvest. Cork harvesting takes place every nine to twelve years when a layer thickness of 2.7 to 4 cm (1 to 1+1⁄2 in) is reached. Under favorable (warm) conditions, the harvest can take place every eight years, in North Africa every seven years. A cork oak can be harvested five to seventeen times in total.[24] In order to minimize the damage to the trunk surface, harvesting can be carried out every three years, whereby only a third of the usable surface is removed. An important maintenance measure is pruning, which begins around the age of ten at a height of about 3 m (10 ft). Some sources say an oak can provide around 100 to 200 kilograms (220 to 440 pounds) of cork over its lifespan, and one hectare around 200 to 500 kg (440 to 1,100 lb) per year[25] while others suggest a single tree can produce on average 40 to 60 kg (88 to 132 lb) of cork per harvest,[24] a comparatively higher value, as cork oaks can live more than 200 years in good conditions.[16][1]

The cork is mainly used for the production of stoppers and corks, as well as for heat and sound insulation, cork paper, badminton shuttlecocks, cricket balls, handles of fishing rods and hand tools, special devices for the space industry[22] and for other technical applications (including composite materials, shoe soles, floor coverings).[25][26] Bottle cork production accounts for around 70% of the added value in cork cultivation. Since natural corks are increasingly being replaced by plastic or sheet metal closures, there could be a significant decline in the cork oak population in southwestern Europe, which endangers the biodiversity in these areas.[25]

The bark, which contains around twelve percent extractable tannin, is also used. In addition, the acorns are used as feed in extensive pig fattening (acorn fattening). One tree can provide 15 to 30 kg (33 to 66 lb) of acorns per year.[25]

Cork oaks cannot legally be cut down in Portugal, except for forest management felling of old, unproductive trees, and, even in those cases, farmers need special permission from the Ministry of Agriculture.[27][1]

Cork harvesting is done entirely without machinery, being dependent solely on human labour. Usually five people are required to harvest the tree's bark, using a small axe. The process mandates specialized training due to the skill required to harvest bark without inflicting too much damage to the tree.[28]

The European cork industry produces 300,000 tonnes of cork a year, with a value of €1.5 billion and employing 30,000 people. Wine corks represent 15% of cork usage by weight but 66% of revenues.

Cork oaks are sometimes planted as individual trees, providing a minor income to their owners. The tree is also sometimes cultivated for ornament. Hybrids with Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) are not uncommon, both where their ranges overlap in the wild in southwest Europe and in cultivation; the hybrid Quercus × hispanica is known as Lucombe oak, for William Lucombe, who first identified it.

Some cork is also produced in eastern Asia from the related Chinese cork oak (Quercus variabilis).

Culture

The cork oak is featured in the city arms of several cities in Portugal, such as the city of Reguengos de Monsaraz, which shows a freshly harvested cork tree.[29]

In 2007, a 2 euro commemorative coin with the motif of a cork oak was issued in Portugal in memory of the Portuguese Presidency of the European Union.[30]

Notable trees

In the Portuguese town of Águas de Moura lies the Sobreiro Monumental (Monumental Cork Oak), also known as 'The Whistler Tree', a tree 236 years old (planted in 1783/1784), over 14 metres (46 ft) tall and with a trunk that requires at least three people to embrace it. It has been considered a National Monument since 1988, and Guinness World Records lists it as the largest cork tree in the world.[31][32]

References

- Barstow, M.; Harvey-Brown, Y. (2017). "Quercus suber". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T194237A2305530. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T194237A2305530.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Quercus suber L.". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List.

- Eriksson, E.; Varela, M.C.; Lumaret, R. & Gil, L. (2017). Genetic conservation of Quercus suber (PDF). European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN), Bioversity International. ISBN 978-92-9255-062-2.

- "Put a cork in it!". WWF. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 501. Schütt et al.

- "Quercus suber L." (PDF). Flora Iberica. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 503. Schütt et al.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 502. Schütt et al.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 500. Schütt et al.

- Genaust, Helmut (2005). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der botanischen Pflanzennamen (3., vollständig überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage ed.). Hamburg. pp. 523 and 618. ISBN 3-937872-16-7.

- "Information Bureau: 2019 Cork Sector in Numbers - APCOR" (PDF). APCOR. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- J. Heller. "Quercus suber L." Mansfeld’s World Database of Agricultural and Horticultural Crops.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 504. Schütt et al.

- Mediterranean Woodland and Forest Ecoregion: Northern Africa: Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. World Wildlife Fund. 2017.

- Rodríguez, A. & Calzada, J. (2015). "Lynx pardinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T12520A174111773. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Santos Pereira, J., Bugalho, M.N., and Caldeira, M.D. (2008). From the Cork Oak to Cork: A Sustainable Ecosystem. APCOR: Portuguese Cork Association.

- BirdLife International (2019). "Aquila adalberti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22696042A152593918. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Hogan, C. M. Barbary Macaque, Macaca sylvanus. GlobalTwitcher.com, Ed. N. Stromberg.

- Moricca, Salvatore; Linaldeddu, Benedetto T.; Ginetti, Beatrice; Scanu, Bruno; Franceschini, Antonio; Ragazzi, Alessandro (2016). "Endemic and Emerging Pathogens Threatening Cork Oak Trees: Management Options for Conserving a Unique Forest Ecosystem". Plant Disease. 100 (11): 2184–2193. doi:10.1094/PDIS-03-16-0408-FE. PMID 30682920.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 504-505. Schütt et al.

- Schütt, Schuck (2002). Lexikon der Baum- und Straucharten : das Standardwerk der Forstbotanik. Morphologie, Pathologie, Ökologie und Systematik wichtiger Baum- und Straucharten (Sonderausg ed.). Hamburg: Nikol Verl.-Ges. p. 436. ISBN 3-933203-53-8.

- Gil, L. & Varela, M. (2008), Cork oak - Quercus suber: Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use (PDF), European Forest Genetic Resources Programme, p. 6

- Plieninger, Tobias. "Traditional land-use and nature conservation in rural Europe". Encyclopedia of Earth.

- "Mitos e curiosidades". Amorim. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Enzyklopädie der Laubbäume. Page 505. Schütt et al.

- Pereira (2008), Alexandre. "Biowerkstoff-Report" (PDF). Nova Institute. p. 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-18.

- "Decreto-Lei n.º 169/2001". Diário da República. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Cork harvesting". APCOR. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- "Ordenação Heráldica de Reguengos de Monsaraz". Reguengos de Monsaraz Municipality. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "€2 commemorative coins - 2007". ecb.europa.eu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "Which is the largest and oldest cork oak in the world?". amorim.com. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "The World's Oldest, Largest Cork Tree – The Whistler Tree". vinepair.com. 3 April 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

Further reading

- Aronson J., Pereira J. S., Pausas J. G. (eds.). (2009). Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge: Conservation, Adaptive Management, and Restoration. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 315 pp.

External links

- Quercus suber. Plants of the World Online. Kew Science.

- Cork Oak. World Wildlife Foundation Priority Species.

- Cork Industry Federation. 2014.

- PlanetCork.org. Educating primary school children in sustainable development. Cork Industry Federation. 2009.

- Cork Oak (Quercus suber). European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN).