Abstraction (computer science)

In software engineering and computer science, abstraction is:

- The process of removing or generalizing physical, spatial, or temporal details[2] or attributes in the study of objects or systems to focus attention on details of greater importance;[3] it is similar in nature to the process of generalization;

- the creation of abstract concept-objects by mirroring common features or attributes of various non-abstract objects or systems of study[3] – the result of the process of abstraction.

The essence of abstraction is preserving information that is relevant in a given context, and forgetting information that is irrelevant in that context.

– John V. Guttag[1]

Abstraction, in general, is a fundamental concept in computer science and software development.[4] The process of abstraction can also be referred to as modeling and is closely related to the concepts of theory and design.[5] Models can also be considered types of abstractions per their generalization of aspects of reality.

Abstraction in computer science is closely related to abstraction in mathematics due to their common focus on building abstractions as objects,[2] but is also related to other notions of abstraction used in other fields such as art.[3]

Abstractions may also refer to real-world objects and systems, rules of computational systems or rules of programming languages that carry or utilize features of abstraction itself, such as:

- the usage of data types to perform data abstraction to separate usage from working representations of data structures within programs;[6]

- the concept of procedures, functions, or subroutines which represent a specific of implementing control flow in programs;

- the rules commonly named "abstraction" that generalize expressions using free and bound variables in the various versions of lambda calculus;[7][8]

- the usage of S-expressions as an abstraction of data structures and programs in the Lisp programming language;[9]

- the process of reorganizing common behavior from non-abstract classes into "abstract classes" using inheritance to abstract over sub-classes as seen in the object-oriented C++ and Java programming languages.

Rationale

Computing mostly operates independently of the concrete world. The hardware implements a model of computation that is interchangeable with others.[10] The software is structured in architectures to enable humans to create the enormous systems by concentrating on a few issues at a time. These architectures are made of specific choices of abstractions. Greenspun's Tenth Rule is an aphorism on how such an architecture is both inevitable and complex.

A central form of abstraction in computing is language abstraction: new artificial languages are developed to express specific aspects of a system. Modeling languages help in planning. Computer languages can be processed with a computer. An example of this abstraction process is the generational development of programming languages from the machine language to the assembly language and the high-level language. Each stage can be used as a stepping stone for the next stage. The language abstraction continues for example in scripting languages and domain-specific programming languages.

Within a programming language, some features let the programmer create new abstractions. These include subroutines, modules, polymorphism, and software components. Some other abstractions such as software design patterns and architectural styles remain invisible to a translator and operate only in the design of a system.

Some abstractions try to limit the range of concepts a programmer needs to be aware of, by completely hiding the abstractions that they in turn are built on. The software engineer and writer Joel Spolsky has criticised these efforts by claiming that all abstractions are leaky – that they can never completely hide the details below;[11] however, this does not negate the usefulness of abstraction.

Some abstractions are designed to inter-operate with other abstractions – for example, a programming language may contain a foreign function interface for making calls to the lower-level language.

Abstraction features

Programming languages

Different programming languages provide different types of abstraction, depending on the intended applications for the language. For example:

- In object-oriented programming languages such as C++, Object Pascal, or Java, the concept of abstraction has itself become a declarative statement – using the syntax

function(parameters) = 0;(in C++) or the keywordsabstract[12] andinterface[13] (in Java). After such a declaration, it is the responsibility of the programmer to implement a class to instantiate the object of the declaration. - Functional programming languages commonly exhibit abstractions related to functions, such as lambda abstractions (making a term into a function of some variable) and higher-order functions (parameters are functions).

- Modern members of the Lisp programming language family such as Clojure, Scheme and Common Lisp support macro systems to allow syntactic abstraction. Other programming languages such as Scala also have macros, or very similar metaprogramming features (for example, Haskell has Template Haskell, and OCaml has MetaOCaml). These can allow a programmer to eliminate boilerplate code, abstract away tedious function call sequences, implement new control flow structures, and implement Domain Specific Languages (DSLs), which allow domain-specific concepts to be expressed in concise and elegant ways. All of these, when used correctly, improve both the programmer's efficiency and the clarity of the code by making the intended purpose more explicit. A consequence of syntactic abstraction is also that any Lisp dialect and in fact almost any programming language can, in principle, be implemented in any modern Lisp with significantly reduced (but still non-trivial in some cases) effort when compared to "more traditional" programming languages such as Python, C or Java.

Specification methods

Analysts have developed various methods to formally specify software systems. Some known methods include:

- Abstract-model based method (VDM, Z);

- Algebraic techniques (Larch, CLEAR, OBJ, ACT ONE, CASL);

- Process-based techniques (LOTOS, SDL, Estelle);

- Trace-based techniques (SPECIAL, TAM);

- Knowledge-based techniques (Refine, Gist).

Specification languages

Specification languages generally rely on abstractions of one kind or another, since specifications are typically defined earlier in a project, (and at a more abstract level) than an eventual implementation. The UML specification language, for example, allows the definition of abstract classes, which in a waterfall project, remain abstract during the architecture and specification phase of the project.

Control abstraction

Programming languages offer control abstraction as one of the main purposes of their use. Computer machines understand operations at the very low level such as moving some bits from one location of the memory to another location and producing the sum of two sequences of bits. Programming languages allow this to be done in the higher level. For example, consider this statement written in a Pascal-like fashion:

a := (1 + 2) * 5

To a human, this seems a fairly simple and obvious calculation ("one plus two is three, times five is fifteen"). However, the low-level steps necessary to carry out this evaluation, and return the value "15", and then assign that value to the variable "a", are actually quite subtle and complex. The values need to be converted to binary representation (often a much more complicated task than one would think) and the calculations decomposed (by the compiler or interpreter) into assembly instructions (again, which are much less intuitive to the programmer: operations such as shifting a binary register left, or adding the binary complement of the contents of one register to another, are simply not how humans think about the abstract arithmetical operations of addition or multiplication). Finally, assigning the resulting value of "15" to the variable labeled "a", so that "a" can be used later, involves additional 'behind-the-scenes' steps of looking up a variable's label and the resultant location in physical or virtual memory, storing the binary representation of "15" to that memory location, etc.

Without control abstraction, a programmer would need to specify all the register/binary-level steps each time they simply wanted to add or multiply a couple of numbers and assign the result to a variable. Such duplication of effort has two serious negative consequences:

- it forces the programmer to constantly repeat fairly common tasks every time a similar operation is needed

- it forces the programmer to program for the particular hardware and instruction set

Structured programming

Structured programming involves the splitting of complex program tasks into smaller pieces with clear flow-control and interfaces between components, with a reduction of the complexity potential for side-effects.

In a simple program, this may aim to ensure that loops have single or obvious exit points and (where possible) to have single exit points from functions and procedures.

In a larger system, it may involve breaking down complex tasks into many different modules. Consider a system which handles payroll on ships and at shore offices:

- The uppermost level may feature a menu of typical end-user operations.

- Within that could be standalone executables or libraries for tasks such as signing on and off employees or printing checks.

- Within each of those standalone components there could be many different source files, each containing the program code to handle a part of the problem, with only selected interfaces available to other parts of the program. A sign on program could have source files for each data entry screen and the database interface (which may itself be a standalone third party library or a statically linked set of library routines).

- Either the database or the payroll application also has to initiate the process of exchanging data with between ship and shore, and that data transfer task will often contain many other components.

These layers produce the effect of isolating the implementation details of one component and its assorted internal methods from the others. Object-oriented programming embraces and extends this concept.

Data abstraction

Data abstraction enforces a clear separation between the abstract properties of a data type and the concrete details of its implementation. The abstract properties are those that are visible to client code that makes use of the data type—the interface to the data type—while the concrete implementation is kept entirely private, and indeed can change, for example to incorporate efficiency improvements over time. The idea is that such changes are not supposed to have any impact on client code, since they involve no difference in the abstract behaviour.

For example, one could define an abstract data type called lookup table which uniquely associates keys with values, and in which values may be retrieved by specifying their corresponding keys. Such a lookup table may be implemented in various ways: as a hash table, a binary search tree, or even a simple linear list of (key:value) pairs. As far as client code is concerned, the abstract properties of the type are the same in each case.

Of course, this all relies on getting the details of the interface right in the first place, since any changes there can have major impacts on client code. As one way to look at this: the interface forms a contract on agreed behaviour between the data type and client code; anything not spelled out in the contract is subject to change without notice.

Manual data abstraction

While much of data abstraction occurs through computer science and automation, there are times when this process is done manually and without programming intervention. One way this can be understood is through data abstraction within the process of conducting a systematic review of the literature. In this methodology, data is abstracted by one or several abstractors when conducting a meta-analysis, with errors reduced through dual data abstraction followed by independent checking, known as adjudication.[14]

Abstraction in object oriented programming

In object-oriented programming theory, abstraction involves the facility to define objects that represent abstract "actors" that can perform work, report on and change their state, and "communicate" with other objects in the system. The term encapsulation refers to the hiding of state details, but extending the concept of data type from earlier programming languages to associate behavior most strongly with the data, and standardizing the way that different data types interact, is the beginning of abstraction. When abstraction proceeds into the operations defined, enabling objects of different types to be substituted, it is called polymorphism. When it proceeds in the opposite direction, inside the types or classes, structuring them to simplify a complex set of relationships, it is called delegation or inheritance.

Various object-oriented programming languages offer similar facilities for abstraction, all to support a general strategy of polymorphism in object-oriented programming, which includes the substitution of one type for another in the same or similar role. Although not as generally supported, a configuration or image or package may predetermine a great many of these bindings at compile-time, link-time, or loadtime. This would leave only a minimum of such bindings to change at run-time.

Common Lisp Object System or Self, for example, feature less of a class-instance distinction and more use of delegation for polymorphism. Individual objects and functions are abstracted more flexibly to better fit with a shared functional heritage from Lisp.

C++ exemplifies another extreme: it relies heavily on templates and overloading and other static bindings at compile-time, which in turn has certain flexibility problems.

Although these examples offer alternate strategies for achieving the same abstraction, they do not fundamentally alter the need to support abstract nouns in code – all programming relies on an ability to abstract verbs as functions, nouns as data structures, and either as processes.

Consider for example a sample Java fragment to represent some common farm "animals" to a level of abstraction suitable to model simple aspects of their hunger and feeding. It defines an Animal class to represent both the state of the animal and its functions:

public class Animal extends LivingThing

{

private Location loc;

private double energyReserves;

public boolean isHungry() {

return energyReserves < 2.5;

}

public void eat(Food food) {

// Consume food

energyReserves += food.getCalories();

}

public void moveTo(Location location) {

// Move to new location

this.loc = location;

}

}

With the above definition, one could create objects of type Animal and call their methods like this:

thePig = new Animal();

theCow = new Animal();

if (thePig.isHungry()) {

thePig.eat(tableScraps);

}

if (theCow.isHungry()) {

theCow.eat(grass);

}

theCow.moveTo(theBarn);

In the above example, the class Animal is an abstraction used in place of an actual animal, LivingThing is a further abstraction (in this case a generalisation) of Animal.

If one requires a more differentiated hierarchy of animals – to differentiate, say, those who provide milk from those who provide nothing except meat at the end of their lives – that is an intermediary level of abstraction, probably DairyAnimal (cows, goats) who would eat foods suitable to giving good milk, and MeatAnimal (pigs, steers) who would eat foods to give the best meat-quality.

Such an abstraction could remove the need for the application coder to specify the type of food, so they could concentrate instead on the feeding schedule. The two classes could be related using inheritance or stand alone, and the programmer could define varying degrees of polymorphism between the two types. These facilities tend to vary drastically between languages, but in general each can achieve anything that is possible with any of the others. A great many operation overloads, data type by data type, can have the same effect at compile-time as any degree of inheritance or other means to achieve polymorphism. The class notation is simply a coder's convenience.

Object-oriented design

Decisions regarding what to abstract and what to keep under the control of the coder become the major concern of object-oriented design and domain analysis—actually determining the relevant relationships in the real world is the concern of object-oriented analysis or legacy analysis.

In general, to determine appropriate abstraction, one must make many small decisions about scope (domain analysis), determine what other systems one must cooperate with (legacy analysis), then perform a detailed object-oriented analysis which is expressed within project time and budget constraints as an object-oriented design. In our simple example, the domain is the barnyard, the live pigs and cows and their eating habits are the legacy constraints, the detailed analysis is that coders must have the flexibility to feed the animals what is available and thus there is no reason to code the type of food into the class itself, and the design is a single simple Animal class of which pigs and cows are instances with the same functions. A decision to differentiate DairyAnimal would change the detailed analysis but the domain and legacy analysis would be unchanged—thus it is entirely under the control of the programmer, and it is called an abstraction in object-oriented programming as distinct from abstraction in domain or legacy analysis.

Considerations

When discussing formal semantics of programming languages, formal methods or abstract interpretation, abstraction refers to the act of considering a less detailed, but safe, definition of the observed program behaviors. For instance, one may observe only the final result of program executions instead of considering all the intermediate steps of executions. Abstraction is defined to a concrete (more precise) model of execution.

Abstraction may be exact or faithful with respect to a property if one can answer a question about the property equally well on the concrete or abstract model. For instance, if one wishes to know what the result of the evaluation of a mathematical expression involving only integers +, -, ×, is worth modulo n, then one needs only perform all operations modulo n (a familiar form of this abstraction is casting out nines).

Abstractions, however, though not necessarily exact, should be sound. That is, it should be possible to get sound answers from them—even though the abstraction may simply yield a result of undecidability. For instance, students in a class may be abstracted by their minimal and maximal ages; if one asks whether a certain person belongs to that class, one may simply compare that person's age with the minimal and maximal ages; if his age lies outside the range, one may safely answer that the person does not belong to the class; if it does not, one may only answer "I don't know".

The level of abstraction included in a programming language can influence its overall usability. The Cognitive dimensions framework includes the concept of abstraction gradient in a formalism. This framework allows the designer of a programming language to study the trade-offs between abstraction and other characteristics of the design, and how changes in abstraction influence the language usability.

Abstractions can prove useful when dealing with computer programs, because non-trivial properties of computer programs are essentially undecidable (see Rice's theorem). As a consequence, automatic methods for deriving information on the behavior of computer programs either have to drop termination (on some occasions, they may fail, crash or never yield out a result), soundness (they may provide false information), or precision (they may answer "I don't know" to some questions).

Abstraction is the core concept of abstract interpretation. Model checking generally takes place on abstract versions of the studied systems.

Levels of abstraction

Computer science commonly presents levels (or, less commonly, layers) of abstraction, wherein each level represents a different model of the same information and processes, but with varying amounts of detail. Each level uses a system of expression involving a unique set of objects and compositions that apply only to a particular domain. [15] Each relatively abstract, "higher" level builds on a relatively concrete, "lower" level, which tends to provide an increasingly "granular" representation. For example, gates build on electronic circuits, binary on gates, machine language on binary, programming language on machine language, applications and operating systems on programming languages. Each level is embodied, but not determined, by the level beneath it, making it a language of description that is somewhat self-contained.

Database systems

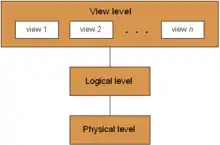

Since many users of database systems lack in-depth familiarity with computer data-structures, database developers often hide complexity through the following levels:

Physical level: The lowest level of abstraction describes how a system actually stores data. The physical level describes complex low-level data structures in detail.

Logical level: The next higher level of abstraction describes what data the database stores, and what relationships exist among those data. The logical level thus describes an entire database in terms of a small number of relatively simple structures. Although implementation of the simple structures at the logical level may involve complex physical level structures, the user of the logical level does not need to be aware of this complexity. This is referred to as physical data independence. Database administrators, who must decide what information to keep in a database, use the logical level of abstraction.

View level: The highest level of abstraction describes only part of the entire database. Even though the logical level uses simpler structures, complexity remains because of the variety of information stored in a large database. Many users of a database system do not need all this information; instead, they need to access only a part of the database. The view level of abstraction exists to simplify their interaction with the system. The system may provide many views for the same database.

Layered architecture

The ability to provide a design of different levels of abstraction can

- simplify the design considerably

- enable different role players to effectively work at various levels of abstraction

- support the portability of software artifacts (model-based ideally)

Systems design and business process design can both use this. Some design processes specifically generate designs that contain various levels of abstraction.

Layered architecture partitions the concerns of the application into stacked groups (layers). It is a technique used in designing computer software, hardware, and communications in which system or network components are isolated in layers so that changes can be made in one layer without affecting the others.

See also

- Abstraction principle (computer programming)

- Abstraction inversion for an anti-pattern of one danger in abstraction

- Abstract data type for an abstract description of a set of data

- Algorithm for an abstract description of a computational procedure

- Bracket abstraction for making a term into a function of a variable

- Data modeling for structuring data independent of the processes that use it

- Encapsulation for abstractions that hide implementation details

- Greenspun's Tenth Rule for an aphorism about an (the?) optimum point in the space of abstractions

- Higher-order function for abstraction where functions produce or consume other functions

- Lambda abstraction for making a term into a function of some variable

- List of abstractions (computer science)

- Refinement for the opposite of abstraction in computing

- Integer (computer science)

- Heuristic (computer science)

References

- Guttag, John V. (18 January 2013). Introduction to Computation and Programming Using Python (Spring 2013 ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262519632.

- Colburn, Timothy; Shute, Gary (5 June 2007). "Abstraction in Computer Science". Minds and Machines. 17 (2): 169–184. doi:10.1007/s11023-007-9061-7. ISSN 0924-6495. S2CID 5927969.

- Kramer, Jeff (1 April 2007). "Is abstraction the key to computing?". Communications of the ACM. 50 (4): 36–42. doi:10.1145/1232743.1232745. ISSN 0001-0782. S2CID 12481509.

- Ben-Ari, Mordechai (1 March 1998). "Constructivism in computer science education". ACM SIGCSE Bulletin. 30 (1): 257, 257–261. doi:10.1145/274790.274308. ISSN 0097-8418.

- Comer, D. E.; Gries, David; Mulder, Michael C.; Tucker, Allen; Turner, A. Joe; Young, Paul R. /Denning (1 January 1989). "Computing as a discipline". Communications of the ACM. 32 (1): 9–23. doi:10.1145/63238.63239. ISSN 0001-0782. S2CID 723103.

- Liskov, Barbara (1 May 1988). "Keynote address – data abstraction and hierarchy". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. ACM. 23: 17–34. doi:10.1145/62138.62141. ISBN 0897912667. S2CID 14219043.

- Barendregt, Hendrik Pieter (1984). The lambda calculus : its syntax and semantics (Revised ed.). Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 0444867481. OCLC 10559084.

- Barendregt, Hendrik Pieter (2013). Lambda calculus with types. Dekkers, Wil., Statman, Richard., Alessi, Fabio., Association for Symbolic Logic. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521766142. OCLC 852197712.

- Newell, Allen; Simon, Herbert A. (1 January 2007). Computer science as empirical inquiry: symbols and search. ACM. p. 1975. doi:10.1145/1283920.1283930. ISBN 9781450310499.

- Floridi, Luciano (September 2008). "The Method of Levels of Abstraction". Minds and Machines. 18 (3): 303–329. doi:10.1007/s11023-008-9113-7. ISSN 0924-6495.

- Spolsky, Joel. "The Law of Leaky Abstractions".

- "Abstract Methods and Classes". The Java™ Tutorials. Oracle. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Using an Interface as a Type". The Java™ Tutorials. Oracle. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- E, Jian‐Yu; Saldanha, Ian J.; Canner, Joseph; Schmid, Christopher H.; Le, Jimmy T.; Li, Tianjing (2020). "Adjudication rather than experience of data abstraction matters more in reducing errors in abstracting data in systematic reviews". Research Synthesis Methods. 11 (3): 354–362. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1396. ISSN 1759-2879. PMID 31955502.

- Luciano Floridi, Levellism and the Method of Abstraction IEG – Research Report 22.11.04

Further reading

- Harold Abelson; Gerald Jay Sussman; Julie Sussman (25 July 1996). Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (2 ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01153-2. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- Spolsky, Joel (11 November 2002). "The Law of Leaky Abstractions". Joel on Software.

- Abstraction/information hiding – CS211 course, Cornell University.

- Eric S. Roberts (1997). Programming Abstractions in C A Second Course in Computer Science.

- Palermo, Jeffrey (29 July 2008). "The Onion Architecture". Jeffrey Palermo.

- Vishkin, Uzi (January 2011). "Using simple abstraction to reinvent computing for parallelism". Communications of the ACM. 54 (1): 75–85. doi:10.1145/1866739.1866757.

External links

- SimArch example of layered architecture for distributed simulation systems.