Sign language

Sign languages (also known as signed languages) are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning, instead of just spoken words. Sign languages are expressed through manual articulation in combination with non-manual markers. Sign languages are full-fledged natural languages with their own grammar and lexicon.[1] Sign languages are not universal and are usually not mutually intelligible,[2] although there are also similarities among different sign languages.

Linguists consider both spoken and signed communication to be types of natural language, meaning that both emerged through an abstract, protracted aging process and evolved over time without meticulous planning.[3] Sign language should not be confused with body language, a type of nonverbal communication.

Wherever communities of deaf people exist, sign languages have developed as useful means of communication and form the core of local Deaf cultures. Although signing is used primarily by the deaf and hard of hearing, it is also used by hearing individuals, such as those unable to physically speak, those who have trouble with oral language due to a disability or condition (augmentative and alternative communication), and those with deaf family members including children of deaf adults.

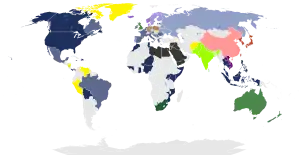

The number of sign languages worldwide is not precisely known. Each country generally has its own native sign language; some have more than one. The 2021 edition of Ethnologue lists 150 sign languages,[4] while the SIGN-HUB Atlas of Sign Language Structures lists over 200 and notes that there are more which have not been documented or discovered yet.[5] As of 2021, Indo Sign Language is the most used sign language in the world, and Ethnologue ranks it as the 151st most "spoken" language in the world.[6]

Some sign languages have obtained some form of legal recognition.[7]

Linguists distinguish natural sign languages from other systems that are precursors to them or obtained from them, such as constructed manual codes for spoken languages, home sign, "baby sign", and signs learned by non-human primates.

History

Groups of deaf people have used sign languages throughout history. One of the earliest written records of a sign language is from the fifth century BC, in Plato's Cratylus, where Socrates says: "If we hadn't a voice or a tongue, and wanted to express things to one another, wouldn't we try to make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body, just as dumb people do at present?"[8] Until the 19th century, most of what is known about historical sign languages is limited to the manual alphabets (fingerspelling systems) that were invented to facilitate the transfer of words from a spoken language to a sign language, rather than documentation of the language itself.

Spanish monk Pedro Ponce de León (1520–1584) developed the first manual alphabet.[9] This alphabet was based, in whole or in part, on the simple hand gestures used by monks living in silence.

In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos ('Reduction of letters and art for teaching mute people to speak') in Madrid.[10] It is considered the first modern treatise of sign language phonetics, setting out a method of oral education for deaf people and a manual alphabet.

In Britain, manual alphabets were also in use for a number of purposes, such as secret communication,[11] public speaking, or communication by or with deaf people.[12] In 1648, John Bulwer described "Master Babington", a deaf man proficient in the use of a manual alphabet, "contryved on the joynts of his fingers", whose wife could converse with him easily, even in the dark through the use of tactile signing.[13]

In 1680, George Dalgarno published Didascalocophus, or, The deaf and dumb mans tutor,[14] in which he presented his own method of deaf education, including an "arthrological" alphabet, where letters are indicated by pointing to different joints of the fingers and palm of the left hand. Arthrological systems had been in use by hearing people for some time;[15] some have speculated that they can be traced to early Ogham manual alphabets.[16][17]

The vowels of this alphabet have survived in the modern alphabets used in British Sign Language, Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language. The earliest known printed pictures of consonants of the modern two-handed alphabet appeared in 1698 with Digiti Lingua (Latin for Language [or Tongue] of the Finger), a pamphlet by an anonymous author who was himself unable to speak.[18][19] He suggested that the manual alphabet could also be used by mutes, for silence and secrecy, or purely for entertainment. Nine of its letters can be traced to earlier alphabets, and 17 letters of the modern two-handed alphabet can be found among the two sets of 26 handshapes depicted.

Charles de La Fin published a book in 1692 describing an alphabetic system where pointing to a body part represented the first letter of the part (e.g. Brow=B), and vowels were located on the fingertips as with the other British systems.[20] He described such codes for both English and Latin.

By 1720, the British manual alphabet had found more or less its present form.[21] Descendants of this alphabet have been used by deaf communities (or at least in classrooms) in the former British colonies India, Australia, New Zealand, Uganda and South Africa, as well as the republics and provinces of the former Yugoslavia, Grand Cayman Island in the Caribbean, Indonesia, Norway, Germany and the United States. During the Polygar Wars against the British, Veeran Sundaralingam communicated with Veerapandiya Kattabomman's mute younger brother, Oomaithurai, by using their own sign language.

Frenchman Charles-Michel de l'Épée published his manual alphabet in the 18th century, which has survived largely unchanged in France and North America until the present time. In 1755, Abbé de l'Épée founded the first school for deaf children in Paris; Laurent Clerc was arguably its most famous graduate. Clerc went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817.[22][23] Gallaudet's son, Edward Miner Gallaudet, founded a school for the deaf in 1857 in Washington, D.C., which in 1864 became the National Deaf-Mute College. Now called Gallaudet University, it is still the only liberal arts university for deaf people in the world.

Sign languages generally do not have any linguistic relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. The correlation between sign and spoken languages is complex and varies depending on the country more than the spoken language. For example, although Australia, English Canada, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S. all have English as their dominant language, American Sign Language (ASL), derived from French Sign Language,[23] is the main sign language used in the U.S. and English Canada, whereas the other three countries use varieties of British, Australian and New Zealand Sign Language, unrelated to ASL.[24] Similarly, the sign languages of Spain and Mexico are very different, despite Spanish being the national language in each country,[25] and the sign language used in Bolivia is based on ASL rather than any sign language that is used in any other Spanish-speaking country.[26] Variations also arise within a 'national' sign language which do not necessarily correspond to dialect differences in the national spoken language; rather, they can usually be correlated to the geographic location of residential schools for the deaf.[27][28]

International Sign, formerly known as Gestuno, is used mainly at international deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf. While recent studies claim that International Sign is a kind of a pidgin, they conclude that it is more complex than a typical pidgin and indeed is more like a full sign language.[29][30] While the more commonly used term is International Sign, it is sometimes referred to as Gestuno,[31] International Sign Pidgin[30] or International Gesture (IG).[32] International Sign is a term used by the World Federation of the Deaf and other international organisations.

Linguistics

In linguistic terms, sign languages are as rich and complex as any spoken language, despite the common misconception that they are not "real languages". Professional linguists have studied many sign languages and found that they exhibit the fundamental properties that exist in all languages.[33][1][34] Such fundamental properties include duality of patterning[35] and recursion.[36] Duality of patterning means that languages are composed of smaller, meaningless units which can be combined into larger units with meaning (see below). The term recursion means that languages exhibit grammatical rules and the output of such a rule can be the input of the same rule. It is, for example, possible in sign languages to create subordinate clauses and a subordinate clause may contain another subordinate clause.

Sign languages are not mime—in other words, signs are conventional, often arbitrary and do not necessarily have a visual relationship to their referent, much as most spoken language is not onomatopoeic. While iconicity is more systematic and widespread in sign languages than in spoken ones, the difference is not categorical.[37] The visual modality allows the human preference for close connections between form and meaning, present but suppressed in spoken languages, to be more fully expressed.[38] This does not mean that sign languages are a visual rendition of a spoken language. They have complex grammars of their own and can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple and concrete to the lofty and abstract. Sign languages are not inventions of educators, or ciphers of the spoken language of the surrounding community.[39]

Sign languages, like spoken languages, organize elementary, meaningless units into meaningful semantic units. This type of organization in natural language is often called duality of patterning. As in spoken languages, these meaningless units are represented as (combinations of) features, although coarser descriptions are often also made in terms of five "parameters": handshape (or handform), orientation, location (or place of articulation), movement, and non-manual expression. (These meaningless units in sign languages were initially called cheremes,[40] from the Greek word for hand, by analogy to the phonemes, from Greek for voice, of spoken languages. Now they are sometimes called phonemes when describing sign languages too, since the function is the same, but more commonly discussed in terms of "features"[1] or "parameters".)[41] More generally, both sign and spoken languages share the characteristics that linguists have found in all natural human languages, such as transitoriness, semanticity, arbitrariness, productivity, and cultural transmission.

Common linguistic features of many sign languages are the occurrence of classifier constructions, a high degree of inflection by means of changes of movement, and a topic-comment syntax. More than spoken languages, sign languages can convey meaning by simultaneous means, e.g. by the use of space, two manual articulators, and the signer's face and body. Though there is still much discussion on the topic of iconicity in sign languages, classifiers are generally considered to be highly iconic, as these complex constructions "function as predicates that may express any or all of the following: motion, position, stative-descriptive, or handling information".[42] It needs to be noted that the term classifier is not used by everyone working on these constructions. Across the field of sign language linguistics the same constructions are also referred with other terms such as depictive signs.

Today, linguists study sign languages as true languages, part of the field of linguistics. However, the category "sign languages" was not added to the Linguistic Bibliography/Bibliographie Linguistique until the 1988 volume,[43] when it appeared with 39 entries.

Relationships with spoken languages

There is a common misconception[44] that sign languages are somehow dependent on spoken languages: that they are spoken language expressed in signs, or that they were invented by hearing people.[45] Similarities in language processing in the brain between signed and spoken languages further perpetuated this misconception. Hearing teachers in deaf schools, such as Charles-Michel de l'Épée or Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, are often incorrectly referred to as "inventors" of sign language. Instead, sign languages, like all natural languages, are developed by the people who use them, in this case, deaf people, who may have little or no knowledge of any spoken language.

As a sign language develops, it sometimes borrows elements from spoken languages, just as all languages borrow from other languages that they are in contact with. Sign languages vary in how much they borrow from spoken languages. In many sign languages, a manual alphabet (fingerspelling) may be used in signed communication to borrow a word from a spoken language, by spelling out the letters. This is most commonly used for proper names of people and places; it is also used in some languages for concepts for which no sign is available at that moment, particularly if the people involved are to some extent bilingual in the spoken language. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, such as initialized signs, in which the handshape represents the first letter of a spoken word with the same meaning.

On the whole, though, sign languages are independent of spoken languages and follow their own paths of development. For example, British Sign Language (BSL) and American Sign Language (ASL) are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of the United Kingdom and the United States share the same spoken language. The grammars of sign languages do not usually resemble those of spoken languages used in the same geographical area; in fact, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English.[46]

Similarly, countries which use a single spoken language throughout may have two or more sign languages, or an area that contains more than one spoken language might use only one sign language. South Africa, which has 11 official spoken languages and a similar number of other widely used spoken languages, is a good example of this. It has only one sign language with two variants due to its history of having two major educational institutions for the deaf which have served different geographic areas of the country.

Spatial grammar and simultaneity

Sign languages exploit the unique features of the visual medium (sight), but may also exploit tactile features (tactile sign languages). Spoken language is by and large linear; only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, on the other hand, is visual and, hence, can use a simultaneous expression, although this is limited articulatorily and linguistically. Visual perception allows processing of simultaneous information.

One way in which many sign languages take advantage of the spatial nature of the language is through the use of classifiers. Classifiers allow a signer to spatially show a referent's type, size, shape, movement, or extent.

The large focus on the possibility of simultaneity in sign languages in contrast to spoken languages is sometimes exaggerated, though. The use of two manual articulators is subject to motor constraints, resulting in a large extent of symmetry[47] or signing with one articulator only. Further, sign languages, just like spoken languages, depend on linear sequencing of signs to form sentences; the greater use of simultaneity is mostly seen in the morphology (internal structure of individual signs).

Non-manual elements

Sign languages convey much of their prosody through non-manual elements. Postures or movements of the body, head, eyebrows, eyes, cheeks, and mouth are used in various combinations to show several categories of information, including lexical distinction, grammatical structure, adjectival or adverbial content, and discourse functions.

At the lexical level, signs can be lexically specified for non-manual elements in addition to the manual articulation. For instance, facial expressions may accompany verbs of emotion, as in the sign for angry in Czech Sign Language. Non-manual elements may also be lexically contrastive. For example, in ASL (American Sign Language), facial components distinguish some signs from other signs. An example is the sign translated as not yet, which requires that the tongue touch the lower lip and that the head rotate from side to side, in addition to the manual part of the sign. Without these features the sign would be interpreted as late.[48] Mouthings, which are (parts of) spoken words accompanying lexical signs, can also be contrastive, as in the manually identical signs for doctor and battery in Sign Language of the Netherlands.[49]

While the content of a signed sentence is produced manually, many grammatical functions are produced non-manually (i.e., with the face and the torso).[50] Such functions include questions, negation, relative clauses and topicalization.[51] ASL and BSL use similar non-manual marking for yes/no questions, for example. They are shown through raised eyebrows and a forward head tilt.[52][53]

Some adjectival and adverbial information is conveyed through non-manual elements, but what these elements are varies from language to language. For instance, in ASL a slightly open mouth with the tongue relaxed and visible in the corner of the mouth means 'carelessly', but a similar non-manual in BSL means 'boring' or 'unpleasant'.[53]

Discourse functions such as turn taking are largely regulated through head movement and eye gaze. Since the addressee in a signed conversation must be watching the signer, a signer can avoid letting the other person have a turn by not looking at them, or can indicate that the other person may have a turn by making eye contact.[54]

Iconicity

Iconicity is similarity or analogy between the form of a sign (linguistic or otherwise) and its meaning, as opposed to arbitrariness. The first studies on iconicity in ASL were published in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Many early sign language linguists rejected the notion that iconicity was an important aspect of sign languages, considering most perceived iconicity to be extralinguistic.[55][33] However, mimetic aspects of sign language (signs that imitate, mimic, or represent) are found in abundance across a wide variety of sign languages. For example, when deaf children learning sign language try to express something but do not know the associated sign, they will often invent an iconic sign that displays mimetic properties.[56] Though it never disappears from a particular sign language, iconicity is gradually weakened as forms of sign languages become more customary and are subsequently grammaticized. As a form becomes more conventional, it becomes disseminated in a methodical way phonologically to the rest of the sign language community.[57] Nancy Frishberg concluded that though originally present in many signs, iconicity is degraded over time through the application of natural grammatical processes.[55]

In 1978, psychologist Roger Brown was one of the first to suggest that the properties of ASL give it a clear advantage in terms of learning and memory.[58] In his study, Brown found that when a group of six hearing children were taught signs that had high levels of iconic mapping they were significantly more likely to recall the signs in a later memory task than another group of six children that were taught signs that had little or no iconic properties. In contrast to Brown, linguists Elissa Newport and Richard Meier found that iconicity "appears to have virtually no impact on the acquisition of American Sign Language".[59]

A central task for the pioneers of sign language linguistics was trying to prove that ASL was a real language and not merely a collection of gestures or "English on the hands." One of the prevailing beliefs at this time was that 'real languages' must consist of an arbitrary relationship between form and meaning. Thus, if ASL consisted of signs that had iconic form-meaning relationship, it could not be considered a real language. As a result, iconicity as a whole was largely neglected in research of sign languages for a long time. However, iconicity also plays a role in many spoken languages. Spoken Japanese for example exhibits many words mimicking the sounds of their potential referents (see Japanese sound symbolism). Later researchers, thus, acknowledged that natural languages do not need to consist of an arbitrary relationship between form and meaning.[60] The visual nature of sign language simply allows for a greater degree of iconicity compared to spoken languages as most real-world objects can be described by a prototypical shape (e.g., a table usually has a flat surface), but most real-world objects do not make prototypical sounds that can be mimicked by spoken languages (e.g., tables do not make prototypical sounds). It has to be noted, however, that sign languages are not fully iconic. On the one hand, there are also many arbitrary signs in sign languages and, on the other hand, the grammar of a sign language puts limits to the degree of iconicity: All known sign languages, for example, express lexical concepts via manual signs. From a truly iconic language one would expect that a concept like smiling would be expressed by mimicking a smile (i.e., by performing a smiling face). All known sign languages, however, do not express the concept of smiling by a smiling face, but by a manual sign.[61]

The cognitive linguistics perspective rejects a more traditional definition of iconicity as a relationship between linguistic form and a concrete, real-world referent. Rather it is a set of selected correspondences between the form and meaning of a sign.[38] In this view, iconicity is grounded in a language user's mental representation ("construal" in cognitive grammar). It is defined as a fully grammatical and central aspect of a sign language rather than a peripheral phenomenon.[62]

The cognitive linguistics perspective allows for some signs to be fully iconic or partially iconic given the number of correspondences between the possible parameters of form and meaning.[63] In this way, the Israeli Sign Language (ISL) sign for ask has parts of its form that are iconic ("movement away from the mouth" means "something coming from the mouth"), and parts that are arbitrary (the handshape, and the orientation).[64]

Many signs have metaphoric mappings as well as iconic or metonymic ones. For these signs there are three-way correspondences between a form, a concrete source and an abstract target meaning. The ASL sign LEARN has this three-way correspondence. The abstract target meaning is "learning". The concrete source is putting objects into the head from books. The form is a grasping hand moving from an open palm to the forehead. The iconic correspondence is between form and concrete source. The metaphorical correspondence is between concrete source and abstract target meaning. Because the concrete source is connected to two correspondences linguistics refer to metaphorical signs as "double mapped".[38][63][64]

Classification

Although sign languages have emerged naturally in deaf communities alongside or among spoken languages, they are unrelated to spoken languages and have different grammatical structures at their core.

Sign languages may be classified by how they arise.

In non-signing communities, home sign is not a full language, but closer to a pidgin. Home sign is amorphous and generally idiosyncratic to a particular family, where a deaf child does not have contact with other deaf children and is not educated in sign. Such systems are not generally passed on from one generation to the next. Where they are passed on, creolization would be expected to occur, resulting in a full language. However, home sign may also be closer to full language in communities where the hearing population has a gestural mode of language; examples include various Australian Aboriginal sign languages and gestural systems across West Africa, such as Mofu-Gudur in Cameroon.

A village sign language is a local indigenous language that typically arises over several generations in a relatively insular community with a high incidence of deafness, and is used both by the deaf and by a significant portion of the hearing community, who have deaf family and friends.[65] The most famous of these is probably the extinct Martha's Vineyard Sign Language of the U.S., but there are also numerous village languages scattered throughout Africa, Asia, and America.

Deaf-community sign languages, on the other hand, arise where deaf people come together to form their own communities. These include school sign, such as Nicaraguan Sign Language, which develop in the student bodies of deaf schools which do not use sign as a language of instruction, as well as community languages such as Bamako Sign Language, which arise where generally uneducated deaf people congregate in urban centers for employment. At first, Deaf-community sign languages are not generally known by the hearing population, in many cases not even by close family members. However, they may grow, in some cases becoming a language of instruction and receiving official recognition, as in the case of ASL.

Both contrast with speech-taboo languages such as the various Aboriginal Australian sign languages, which are developed by the hearing community and only used secondarily by the deaf. It is doubtful whether most of these are languages in their own right, rather than manual codes of spoken languages, though a few such as Yolngu Sign Language are independent of any particular spoken language. Hearing people may also develop sign to communicate with users of other languages, as in Plains Indian Sign Language; this was a contact signing system or pidgin that was evidently not used by deaf people in the Plains nations, though it presumably influenced home sign.

Language contact and creolization is common in the development of sign languages, making clear family classifications difficult – it is often unclear whether lexical similarity is due to borrowing or a common parent language, or whether there was one or several parent languages, such as several village languages merging into a Deaf-community language. Contact occurs between sign languages, between sign and spoken languages (contact sign, a kind of pidgin), and between sign languages and gestural systems used by the broader community. One author has speculated that Adamorobe Sign Language, a village sign language of Ghana, may be related to the "gestural trade jargon used in the markets throughout West Africa", in vocabulary and areal features including prosody and phonetics.[66][67]

- BSL, Auslan and NZSL are usually considered to be a language known as BANZSL. Maritime Sign Language and South African Sign Language are also related to BSL.[68]

- Danish Sign Language and its descendants Norwegian Sign Language and Icelandic Sign Language are largely mutually intelligible with Swedish Sign Language. Finnish Sign Language and Portuguese Sign Language derive from Swedish SL, though with local admixture in the case of mutually unintelligible Finnish SL. Danish SL has French SL influence and Wittmann (1991) places them in that family,[67] though he proposes that Swedish, Finnish, and Portuguese SL are instead related to British Sign Language.

- Indian Sign Language ISL is similar to Pakistani Sign Language. (ISL fingerspelling uses both hands, similarly to British Sign Language.).

- Japanese Sign Language, Taiwanese Sign Language and Korean Sign Language are thought to be members of a Japanese Sign Language family.[69]

- French Sign Language family. There are a number of sign languages that emerged from French Sign Language (LSF), or are the result of language contact between local community sign languages and LSF. These include: French Sign Language, Italian Sign Language, Quebec Sign Language, American Sign Language, Irish Sign Language, Russian Sign Language, Dutch Sign Language (NGT), Spanish Sign Language, Mexican Sign Language, Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS), Catalan Sign Language, Ukrainian Sign Language, Austrian Sign Language (along with its twin Hungarian Sign Language and its offspring Czech Sign Language) and others.

- A subset of this group includes languages that have been heavily influenced by American Sign Language (ASL), or are regional varieties of ASL. Bolivian Sign Language is sometimes considered a dialect of ASL. Thai Sign Language is a mixed language derived from ASL and the native sign languages of Bangkok and Chiang Mai, and may be considered part of the ASL family. Others possibly influenced by ASL include Ugandan Sign Language, Kenyan Sign Language, Philippine Sign Language and Malaysian Sign Language.

- According to an SIL report,[70] the sign languages of Russia, Moldova and Ukraine share a high degree of lexical similarity and may be dialects of one language, or distinct related languages. The same report suggested a "cluster" of sign languages centered around Czech Sign Language, Hungarian Sign Language and Slovak Sign Language. This group may also include Romanian, Bulgarian, and Polish sign languages.

- German Sign Language (DGS) gave rise to Polish Sign Language; it also at least strongly influenced Israeli Sign Language, though it is unclear whether the latter derives from DGS or from Austrian Sign Language, which is in the French family.

- The southern dialect of Chinese Sign Language gave rise to Hong Kong Sign Language, spoken in Hong Kong and Macau

- Lyons Sign Language may be the source of Flemish Sign Language (VGT) though this is unclear.

- Sign languages of Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq (and possibly Saudi Arabia) may be part of a sprachbund, or may be one dialect of a larger Eastern Arabic Sign Language.

- Known isolates include Nicaraguan Sign Language, Turkish Sign Language, Armenian Sign Language, Kata Kolok, Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language and Providence Island Sign Language.

The only comprehensive classification along these lines going beyond a simple listing of languages dates back to 1991.[71] The classification is based on the 69 sign languages from the 1988 edition of Ethnologue that were known at the time of the 1989 conference on sign languages in Montreal and 11 more languages the author added after the conference.[73]

| Primary language |

Primary group |

Auxiliary language |

Auxiliary group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype-A[74] | 5 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| Prototype-R[75] | 18 | 1 | 1 | – |

| BSL-derived | 8 | – | – | – |

| DGS-derived | 1 or 2 | – | – | – |

| JSL-derived | 2 |

– |

– | – |

| LSF-derived | 30 | – | – | – |

| LSG-derived |

1? |

– | – | – |

In his classification, the author distinguishes between primary and auxiliary sign languages[76] as well as between single languages and names that are thought to refer to more than one language.[77] The prototype-A class of languages includes all those sign languages that seemingly cannot be derived from any other language.[74] Prototype-R languages are languages that are remotely modelled on a prototype-A language (in many cases thought to have been French Sign Language) by a process Kroeber (1940) called "stimulus diffusion".[75] The families of BSL, DGS, JSL, LSF (and possibly LSG) were the products of creolization and relexification of prototype languages.[78] Creolization is seen as enriching overt morphology in sign languages, as compared to reducing overt morphology in spoken languages.[79]

Typology

Linguistic typology (going back to Edward Sapir) is based on word structure and distinguishes morphological classes such as agglutinating/concatenating, inflectional, polysynthetic, incorporating, and isolating ones.

Sign languages vary in word-order typology. For example, Austrian Sign Language, Japanese Sign Language and Indo-Pakistani Sign Language are Subject-object-verb while ASL is Subject-verb-object. Influence from the surrounding spoken languages is not improbable.

Sign languages tend to be incorporating classifier languages, where a classifier handshape representing the object is incorporated into those transitive verbs which allow such modification. For a similar group of intransitive verbs (especially motion verbs), it is the subject which is incorporated. Only in a very few sign languages (for instance Japanese Sign Language) are agents ever incorporated. In this way, since subjects of intransitives are treated similarly to objects of transitives, incorporation in sign languages can be said to follow an ergative pattern.

Brentari[80][81] classifies sign languages as a whole group determined by the medium of communication (visual instead of auditory) as one group with the features monosyllabic and polymorphemic. That means, that one syllable (i.e. one word, one sign) can express several morphemes, e.g., subject and object of a verb determine the direction of the verb's movement (inflection).

Another aspect of typology that has been studied in sign languages is their systems for cardinal numbers.[82] Typologically significant differences have been found between sign languages.

Acquisition

Children who are exposed to a sign language from birth will acquire it, just as hearing children acquire their native spoken language.[83]

The Critical Period hypothesis suggests that language, spoken or signed, is more easily acquired as a child at a young age versus an adult because of the plasticity of the child's brain. In a study done at the University of McGill, they found that American Sign Language users who acquired the language natively (from birth) performed better when asked to copy videos of ASL sentences than ASL users who acquired the language later in life. They also found that there are differences in the grammatical morphology of ASL sentences between the two groups, all suggesting that there is a very important critical period in learning signed languages.[84]

The acquisition of non-manual features follows an interesting pattern: When a word that always has a particular non-manual feature associated with it (such as a wh-question word) is learned, the non-manual aspects are attached to the word but don't have the flexibility associated with adult use. At a certain point, the non-manual features are dropped and the word is produced with no facial expression. After a few months, the non-manuals reappear, this time being used the way adult signers would use them.[85]

Written forms

Sign languages do not have a traditional or formal written form. Many deaf people do not see a need to write their own language.[86]

Several ways to represent sign languages in written form have been developed.

- Stokoe notation, devised by Dr. William Stokoe for his 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language,[87] is an abstract phonemic notation system. Designed specifically for representing the use of the hands, it has no way of expressing facial expression or other non-manual features of sign languages. However, his was designed for research, particularly in a dictionary, not for general use.

- The Hamburg Notation System (HamNoSys), developed in the early 1990s, is a detailed phonetic system, not designed for any one sign language, and intended as a transcription system for researchers rather than as a practical script.

- David J. Peterson has attempted to create a phonetic transcription system for signing that is ASCII-friendly known as the Sign Language International Phonetic Alphabet (SLIPA).

- SignWriting, developed by Valerie Sutton in 1974, is a system for representing sign languages phonetically (including mouthing, facial expression and dynamics of movement). The script is sometimes used for detailed research, language documentation, as well as publishing texts and works in sign languages.

- si5s is another orthography which is largely phonemic. However, a few signs are logographs and/or ideographs due to regional variation in sign languages.

- ASL-phabet is a system designed primarily for education of deaf children by Dr. Sam Supalla which uses a minimalist collection of symbols in the order of Handshape-Location-Movement. Many signs can be written the same way (homograph).

- The Alphabetic Writing System for sign languages (Sistema de escritura alfabética, SEA, by its Spanish name and acronym), developed by linguist Ángel Herrero Blanco and two deaf researchers, Juan José Alfaro and Inmacualada Cascales, was published as a book in 2003[88] and made accessible in Spanish Sign Language on-line.[89] This system makes use of the letters of the Latin alphabet with a few diacritics to represent sign through the morphemic sequence S L C Q D F (bimanual sign, place, contact, handshape, direction and internal form). The resulting words are meant to be read by signing. The system is designed to be applicable to any sign language with minimal modification and to be usable through any medium without special equipment or software. Non-manual elements can be encoded to some extent, but the authors argue that the system does not need to represent all elements of a sign to be practical, the same way written oral language doesn't. The system has seen some updates which are kept publicly on a wiki page.[90] The Center for Linguistic Normalization of Spanish Sign Language has made use of SEA to transcribe all signs on its dictionary.[91]

So far, there is no consensus regarding the written form of sign language. Except for SignWriting, none are widely used. Maria Galea writes that SignWriting "is becoming widespread, uncontainable and untraceable. In the same way that works written in and about a well developed writing system such as the Latin script, the time has arrived where SW is so widespread, that it is impossible in the same way to list all works that have been produced using this writing system and that have been written about this writing system."[92] In 2015, the Federal University of Santa Catarina accepted a dissertation written in Brazilian Sign Language using Sutton SignWriting for a master's degree in linguistics. The dissertation "The Writing of Grammatical Non-Manual Expressions in Sentences in LIBRAS Using the SignWriting System" by João Paulo Ampessan states that "the data indicate the need for [non-manual expressions] usage in writing sign language".[93]

Sign perception

For a native signer, sign perception influences how the mind makes sense of their visual language experience. For example, a handshape may vary based on the other signs made before or after it, but these variations are arranged in perceptual categories during its development. The mind detects handshape contrasts but groups similar handshapes together in one category.[94][95][96] Different handshapes are stored in other categories. The mind ignores some of the similarities between different perceptual categories, at the same time preserving the visual information within each perceptual category of handshape variation.

In society

Deaf communities and Deaf culture

When Deaf people constitute a relatively small proportion of the general population, Deaf communities often develop that are distinct from the surrounding hearing community.[97] These Deaf communities are very widespread in the world, associated especially with sign languages used in urban areas and throughout a nation, and the cultures they have developed are very rich.

One example of sign language variation in the Deaf community is Black ASL. This sign language was developed in the Black Deaf community as a variant during the American era of segregation and racism, where young Black Deaf students were forced to attend separate schools than their white Deaf peers.[98]

Use of sign languages in hearing communities

On occasion, where the prevalence of deaf people is high enough, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community, forming what is sometimes called a "village sign language"[99] or "shared signing community".[100] Typically this happens in small, tightly integrated communities with a closed gene pool. Famous examples include:

- Martha's Vineyard Sign Language, United States

- Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, Israel

- Kata Kolok, Bali

- Adamorobe Sign Language, Ghana

- Yucatec Maya Sign Language, Mexico

In such communities deaf people are generally well-integrated in the general community and not socially disadvantaged, so much so that it is difficult to speak of a separate "Deaf" community.[97]

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, and Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

A sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America (see Plains Indian Sign Language) before European contact. It was used by hearing people to communicate among tribes with different spoken languages, as well as by deaf people. There are especially users today among the Crow, Cheyenne, and Arapaho.

Sign language is also used as a form of alternative or augmentative communication by people who can hear but have difficulties using their voices to speak.[101]

Increasingly, hearing schools and universities are expressing interest in incorporating sign language. In the U.S., enrollment for ASL (American Sign Language) classes as part of students' choice of second language is on the rise.[102] In New Zealand, one year after the passing of NZSL Act 2006 in parliament, a NZSL curriculum was released for schools to take NZSL as an optional subject. The curriculum and teaching materials were designed to target intermediate schools from Years 7 to 10, (NZ Herald, 2007).

Legal recognition

Some sign languages have obtained some form of legal recognition, while others have no status at all. Sarah Batterbury has argued that sign languages should be recognized and supported not merely as an accommodation for those with disabilities, but as the communication medium of language communities.[103]

Legal requirements covering sign language accessibility in media vary from country to country. In the United Kingdom, the Broadcasting Act 1996 addressed the requirements for blind and deaf viewers,[104] but has since been replaced by the Communications Act 2003.

Interpretation

In order to facilitate communication between deaf and hearing people, sign language interpreters are often used. Such activities involve considerable effort on the part of the interpreter, since sign languages are distinct natural languages with their own syntax, different from any spoken language.

The interpretation flow is normally between a sign language and a spoken language that are customarily used in the same country, such as French Sign Language (LSF) and spoken French in France, Spanish Sign Language (LSE) to spoken Spanish in Spain, British Sign Language (BSL) and spoken English in the U.K., and American Sign Language (ASL) and spoken English in the U.S. and most of anglophone Canada (since BSL and ASL are distinct sign languages both used in English-speaking countries), etc. Sign language interpreters who can translate between signed and spoken languages that are not normally paired (such as between LSE and English), are also available, albeit less frequently.

Sign language is sometimes provided for television programmes that include speech. The signer usually appears in the bottom corner of the screen, with the programme being broadcast full size or slightly shrunk away from that corner. Typically for press conferences such as those given by the Mayor of New York City, the signer appears to stage left or right of the public official to allow both the speaker and signer to be in frame at the same time. Live sign interpretation of important televised events is increasingly common but still an informal industry [105] In traditional analogue broadcasting, some programmes are repeated outside main viewing hours with a signer present.[106] Some emerging television technologies allow the viewer to turn the signer on and off in a similar manner to subtitles and closed captioning.[106]

Technology

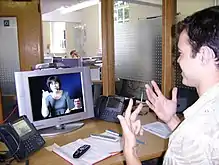

One of the first demonstrations of the ability for telecommunications to help sign language users communicate with each other occurred when AT&T's videophone (trademarked as the Picturephone) was introduced to the public at the 1964 New York World's Fair – two deaf users were able to freely communicate with each other between the fair and another city.[107] However, video communication did not become widely available until sufficient bandwidth for the high volume of video data became available in the early 2000s.

The Internet now allows deaf people to talk via a video link, either with a special-purpose videophone designed for use with sign language or with "off-the-shelf" video services designed for use with broadband and an ordinary computer webcam. The special videophones that are designed for sign language communication may provide better quality than 'off-the-shelf' services and may use data compression methods specifically designed to maximize the intelligibility of sign languages. Some advanced equipment enables a person to remotely control the other person's video camera, in order to zoom in and out or to point the camera better to understand the signing.

Interpreters may be physically present with both parties to the conversation but, since the technological advancements in the early 2000s, provision of interpreters in remote locations has become available. In video remote interpreting (VRI), the two clients (a sign language user and a hearing person who wish to communicate with each other) are in one location, and the interpreter is in another. The interpreter communicates with the sign language user via a video telecommunications link, and with the hearing person by an audio link. VRI can be used for situations in which no on-site interpreters are available.

However, VRI cannot be used for situations in which all parties are speaking via telephone alone. With video relay service (VRS), the sign language user, the interpreter, and the hearing person are in three separate locations, thus allowing the two clients to talk to each other on the phone through the interpreter.

With recent developments in artificial intelligence in computer science, some recent deep learning based machine translation algorithms have been developed which automatically translate short videos containing sign language sentences (often simple sentence consists of only one clause) directly to written language.[108]

Sign Union flag

The Sign Union flag was designed by Arnaud Balard. After studying flags around the world and vexillology principles for two years, Balard revealed the design of the flag, featuring the stylized outline of a hand. The three colors which make up the flag design are representative of Deafhood and humanity (dark blue), sign language (turquoise), and enlightenment and hope (yellow). Balard intended the flag to be an international symbol which welcomes deaf people.[109]

Language endangerment and extinction

As with any spoken language, sign languages are also vulnerable to becoming endangered.[110] For example, a sign language used by a small community may be endangered and even abandoned as users shift to a sign language used by a larger community, as has happened with Hawai'i Sign Language, which is almost extinct except for a few elderly signers.[111][112] Even nationally recognised sign languages can be endangered; for example, New Zealand Sign Language is losing users.[113] Methods are being developed to assess the language vitality of sign languages.[114]

- Endangered sign languages

- Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL)[115]

- Ban Khor Sign Language (BKSL)[115]

- Benkala Sign Language (KK)[115]

- Finland-Swedish Sign Language (FinSSL)[116]

- Hawai'i Sign Language (HPSL)[115]

- Inuit Sign Language (IUR)[117]

- Jamaican Country Sign Language (KS)[118]

- Maritime Sign Language (MSL)[115]

- Old Bangkok Sign Language (OBSL)[115]

- Old Chiangmai Sign Language (OCSL)[115]

- Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL)[115]

- Providencia Sign Language (PSL)[115]

- Rennellese Sign Language (RSL)[115]

- Extinct sign languages

- Angami Naga Sign Language

- Belgian Sign Language (BGT)

- Henniker Sign Language

- Martha's Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL)

- Ngarrindjeri sign language

- Old French Sign Language (VLSF)

- Old Kentish Sign Language (OKSL)

- Pitta Pitta sign language

- Plateau Sign Language

- Sandy River Valley Sign Language

- Warluwarra sign language

Communication systems similar to sign language

There are a number of communication systems that are similar in some respects to sign languages, while not having all the characteristics of a full sign language, particularly its grammatical structure. Many of these are either precursors to natural sign languages or are derived from them.

Manual codes for spoken languages

When Deaf and Hearing people interact, signing systems may be developed that use signs drawn from a natural sign language but used according to the grammar of the spoken language. In particular, when people devise one-for-one sign-for-word correspondences between spoken words (or even morphemes) and signs that represent them, the system that results is a manual code for a spoken language, rather than a natural sign language. Such systems may be invented in an attempt to help teach Deaf children the spoken language, and generally are not used outside an educational context.

"Baby sign language" with hearing children

Some hearing parents teach signs to young hearing children. Since the muscles in babies' hands grow and develop quicker than their mouths, signs are seen as a beneficial option for better communication.[119] Babies can usually produce signs before they can speak. This reduces the confusion between parents when trying to figure out what their child wants. When the child begins to speak, signing is usually abandoned, so the child does not progress to acquiring the grammar of the sign language.

This is in contrast to hearing children who grow up with Deaf parents, who generally acquire the full sign language natively, the same as Deaf children of Deaf parents.

Home sign

Informal, rudimentary sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, the child may develop a system of signs naturally, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes "kitchen sign").[120]

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child naturally invents signs to help meet his or her communication needs, and may even develop a few grammatical rules for combining short sequences of signs. Still, this kind of system is inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and it comes nowhere near meeting the standards linguists use to describe a complete language. No type of home sign is recognized as a full language.[121]

Primate use

There have been several notable examples of scientists teaching signs to non-human primates in order to communicate with humans,[122] such as chimpanzees,[123][124][125][126][127][128][129] gorillas[130] and orangutans.[131] However, linguists generally point out that this does not constitute knowledge of a human language as a complete system, rather than simply signs/words.[132][133][134][135][136] Notable examples of animals who have learned signs include:

- Chimpanzees: Washoe, Nim Chimpsky and Loulis

- Gorillas: Koko and Michael

Gestural theory of human language origins

One theory of the evolution of human language states that it developed first as a gestural system, which later shifted to speech.[137][138][139][140][67][141] An important question for this gestural theory is what caused the shift to vocalization.[142][143][144]

See also

- Animal language

- Body language

- Braille

- Fingerspelling

- Chereme

- Chinese number gestures

- Gang signal

- Gestures

- Intercultural competence

- International Sign

- Legal recognition of sign languages

- List of international common standards

- List of sign languages

- List of sign languages by number of native signers

- Manual communication

- Metacommunicative competence

- Modern Sign Language communication

- Origin of language

- Origin of speech

- Sign language glove

- Sign language in infants and toddlers

- Sign language media

- Sign Language Studies (journal)

- Sign name

- Sociolinguistics of sign languages

- Tactile signing

- Machine translation of sign languages

References

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2006). Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- "What is Sign Language?". Linguistic society. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- E.g.: Irit Meir, Wendy Sandler, Carol Padden, and Mark Aronoff (2010): Emerging Sign Languages. In: Marc Marschark and Patricia Elizabeth Spencer (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education, Vol. 2, pp. 267–80.

- Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2021), "Sign language", Ethnologue: Languages of the World (24th ed.), SIL International, retrieved 2021-05-15

- Hosemann, Jana; Steinbach, Markus, eds. (2021), Atlas of Sign Language Structures, Sign-hub, archived from the original on 2021-04-13, retrieved 2021-01-13

- What are the top 200 most spoken languages?, Ethnologue.

- Wheatley, Mark & Annika Pabsch (2012). Sign Language Legislation in the European Union – Edition II. European Union of the Deaf.

- Bauman, Dirksen (2008). Open your eyes: Deaf studies talking. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4619-7.

- Nielsen, Kim (2012). A Disability History of the United States. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-080702204-7.

- Pablo Bonet, J. de (1620) Reduction de las letras y Arte para enseñar á ablar los Mudos. Ed. Abarca de Angulo, Madrid, ejemplar facsímil accesible en la "Reduction de las letras y arte para enseñar a ablar los mudos". Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library. Archived from the original on 2021-10-04. Retrieved 2021-10-17., online (Spanish) scan of book.

- Wilkins, John (1641). Mercury, the Swift and Silent Messenger. The book is a work on cryptography, and fingerspelling was referred to as one method of "secret discoursing, by signes and gestures". Wilkins gave an example of such a system: "Let the tops of the fingers signifie the five vowels; the middle parts, the first five consonants; the bottomes of them, the five next consonants; the spaces betwixt the fingers the foure next. One finger laid on the side of the hand may signifie T. Two fingers V the consonant; Three W. The little finger crossed X. The wrist Y. The middle of the hand Z." (1641:116–117)

- John Bulwer's "Chirologia: or the natural language of the hand.", published in 1644, London, mentions that alphabets are in use by deaf people, although Bulwer presents a different system which is focused on public speaking.

- Bulwer, J. (1648) Philocopus, or the Deaf and Dumbe Mans Friend, London: Humphrey and Moseley.

- Dalgarno, George. Didascalocophus, or, The deaf and dumb mans tutor. Oxford: Halton, 1680.

- See Wilkins (1641) above. Wilkins was aware that the systems he describes are old, and refers to Bede's account of Roman and Greek finger alphabets.

- "Session 9". Bris.ac.uk. 2000-11-07. Archived from the original on 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- Montgomery, G. (2002). "The Ancient Origins of Sign Handshapes" (PDF). Sign Language Studies. 2 (3): 322–334. doi:10.1353/sls.2002.0010. JSTOR 26204860. S2CID 144243540.

- Moser, Henry M.; O'Neill, John J.; Oyer, Herbert J.; Wolfe, Susan M.; Abernathy, Edward A.; Schowe, Ben M. (1960). "Historical Aspects of Manual Communication". Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 25 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1044/jshd.2502.145. PMID 14424535.

- Hay, A. and Lee, R. (2004) A Pictorial History of the evolution of the British Manual Alphabet. British Deaf History Society Publications: Middlesex

- Charles de La Fin (1692). Sermo mirabilis, or, The silent language whereby one may learn ... how to impart his mind to his friend, in any language ... being a wonderful art kept secret for several ages in Padua, and now published only to the wise and prudent ... London, Printed for Tho. Salusbury... and sold by Randal Taylor... 1692. OCLC 27245872

- Daniel Defoe (1720). "The Life and Adventures of Mr. Duncan Campbell"

- Canlas, Loida (2006). "Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World". The Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University.

- "How Sign Language Works". Stuff You Should Know. 2014-02-06. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- "Ethnologue report for language code: bfi". Ethnologue.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-09. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- "SIL Electronic Survey Reports: Spanish Sign Language survey" (PDF). Sil.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- "SIL Electronic Survey Reports: Bolivia deaf community and sign language pre-survey report" (PDF). Sil.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- Lucas, Ceil, Robert Bayley and Clayton Valli. 2001. Sociolinguistic Variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Lucas, Ceil, Bayley, Robert, Clayton Valli. (2003). What's Your Sign for PIZZA? An Introduction to Variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Cf. Supalla, Ted & Rebecca Webb (1995). "The grammar of international sign: A new look at pidgin languages." In: Emmorey, Karen & Judy Reilly (eds). Language, gesture, and space. (International Conference on Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research) Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, pp. 333–352

- McKee, Rachel; Napier, Jemina (2002). "Interpreting into International Sign Pidgin". Sign Language & Linguistics. 5 (1): 27–54. doi:10.1075/sll.5.1.04mck.

- Rubino, F., Hayhurst, A., and Guejlman, J. (1975). Gestuno. International sign language of the deaf. Carlisle: British Deaf Association.

- Bar-Tzur, David (2002). International gesture: Principles and gestures website

Moody, W. (1987).International gesture. In J. V. Van Cleve (ed.), "Gallaudet encyclopedia of deaf people and deafness", Vol 3 S-Z, Index. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc. - Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1979). The signs of language. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80795-2.

- Baker, Anne; Bogaerde, Beppie van den; Pfau, Roland; Schermer, G. M. (2016). The Linguistics of Sign Languages: An Introduction. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 978-90-272-1230-6.

- Stokoe, William C. 1960. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine, Studies in linguistics: Occasional papers (No. 8). Buffalo: Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo.

- Bross, Fabian (2020). The clausal syntax of German Sign Language. A cartographic approach. Berlin: Language Science Press. Page 37-38.

- Johnston, Trevor A. (1989). Auslan: The Sign Language of the Australian Deaf community. The University of Sydney: unpublished Ph.D. dissertation.

- Taub, S. (2001). Language from the body. New York : Cambridge University Press.

- Pinker, Steven. The Language Instinct. Penguin Books. p. 36.

- Fabian Bross (2016). "Chereme" Archived 2018-03-17 at the Wayback Machine. In: Hall, T. A. Pompino-Marschall, B. (ed.): Dictionaries of Linguistics and Communication Science. Volume: Phonetics and Phonology. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Vicars, Bill. "American Sign Language: "parameters"". ASL University. Bill Vicars. Retrieved 2021-08-13.

- Emmorey, K. (2002). Language, cognition and the brain: Insights from sign language research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Janse, Mark; Borkent, Hans; Tol, Sijmen, eds. (1990). Linguistic Bibliography for the Year 1988. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. pp. 970–972. ISBN 978-07-92-30936-9.

- Pirot, Khunaw Sulaiman; Ali, Wrya Izaddin (2021-09-29). "The Common Misconceptions about Sign Language". Journal of University of Raparin. 8 (3): 110–132. doi:10.26750/Vol(8).No(3).Paper6. ISSN 2522-7130. S2CID 244246983.

- Perlmutter, David M. "What is Sign Language?" (PDF). LSA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- Nakamura, Karen. (1995). "About American Sign Language." Deaf Resource Library, Yale University.

- Battison, Robbin (1978). Lexical Borrowing in American Sign Language. Silver Spring, MD: Linstok Press.

- Liddell, Scott K. (2003). Grammar, Gesture, and Meaning in American Sign Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Josep Quer i Carbonell; Carlo Cecchetto; Rannveig Sverrisd Ãttir, eds. (2017). SignGram blueprint: A guide to sign language grammar writing. De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 9781501511806. OCLC 1012688117.

- Bross, Fabian; Hole, Daniel. "Scope-taking strategies in German Sign Language". Glossa. 2 (1): 1–30. doi:10.5334/gjgl.106.

- Boudreault, Patrick; Mayberry, Rachel I. (2006). "Grammatical processing in American Sign Language: Age of first-language acquisition effects in relation to syntactic structure". Language and Cognitive Processes. 21 (5): 608–635. doi:10.1080/01690960500139363. S2CID 13572435.

- Baker, Charlotte, and Dennis Cokely (1980). American Sign Language: A teacher's resource text on grammar and culture. Silver Spring, MD: T.J. Publishers.

- Sutton-Spence, Rachel, and Bencie Woll (1998). The linguistics of British Sign Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baker, Charlotte (1977). Regulators and turn-taking in American Sign Language discourse, in Lynn Friedman, On the other hand: New perspectives on American Sign Language. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 9780122678509

- Frishberg, N (1975). "Arbitrariness and Iconicity: Historical Change in America". Language. 51 (3): 696–719. doi:10.2307/412894. JSTOR 412894.

- Klima, Edward; Bellugi, Ursula (1989). "The Signs of Language". Sign Language Studies. 1062 (1): 11.

- Brentari, Diane. "Introduction." Sign Languages, 2011, pp. 12.

- Brown, R (1978). "Why Are Signed Languages Easier to Learn than Spoken Languages? Part Two". Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 32 (3): 25–44. doi:10.2307/3823113. JSTOR 3823113.

- Newport, Elissa; Meier, Richard (1985). The crosslinguistic study of language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 881–938. ISBN 0898593670.

- For the history of research on iconicity in sign languages see, for example: Vermeerbergen, Myriam (2006): Past and current trends in sign language research. In: Language & Communication, 26(2). 168-192.

- Bross, Fabian (2020). The clausal syntax of German Sign Language. A cartographic approach. Berlin: Language Science Press. Page 25.

- Wilcox, S (2004). "Conceptual spaces and embodied actions: Cognitive iconicity and signed languages". Cognitive Linguistics. 15 (2): 119–47. doi:10.1515/cogl.2004.005.

- Wilcox, P. (2000). Metaphor in American Sign Language. Washington D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- Meir, I (2010). "Iconicity and metaphor: Constraints on metaphorical extension of iconic forms". Language. 86 (4): 865–96. doi:10.1353/lan.2010.0044. S2CID 117619041.

- Meir, Irit; Sandler, Wendy; Padden, Carol; Aronoff, Mark (2010). "Chapter 18: Emerging sign languages" (PDF). In Marschark, Marc; Spencer, Patricia Elizabeth (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education. Vol. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539003-2. OCLC 779907637. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- Frishberg, Nancy (1987). "Ghanaian Sign Language." In: Cleve, J. Van (ed.), Gallaudet encyclopaedia of deaf people and deafness. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 9780070792296

- Wittmann, H. (1991). Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement. Revue québécoise de linguistique théorique et appliquée, 10(1), 88.

- See Gordon (2008), under nsr "Maritime Sign Language". Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2011-06-01. and sfs "South African Sign Language". Archived from the original on 2008-09-21. Retrieved 2008-09-19..

- Fischer, Susan D. et al. (2010). "Variation in East Asian Sign Language Structures" in Sign Languages,, p. 499, at Google Books

- "SIL Electronic Survey Reports: The signed languages of Eastern Europe". 2012-01-14. Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2021-08-23.

- Henri Wittmann (1991). The classification is said to be typological satisfying Jakobson's condition of genetic interpretability.

- Simons, Gary F.; Charles D. Fennig, eds. (2018). "Bibliography of Ethnologue Data Sources". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (21st ed.). SIL International. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- Wittmann's classification went into Ethnologue's database where it is still cited.[72] The subsequent edition of Ethnologue in 1992 went up to 81 sign languages, ultimately adopting Wittmann's distinction between primary and alternate sign languages (going back ultimately to Stokoe 1974) and, more vaguely, some other traits from his analysis. The 2013 version (17th edition) of Ethnologue is now up to 137 sign languages.

- These are Adamorobe Sign Language, Armenian Sign Language, Australian Aboriginal sign languages, Hindu mudra, the Monastic sign languages, Martha's Vineyard Sign Language, Plains Indian Sign Language, Urubú-Kaapor Sign Language, Chinese Sign Language, Indo-Pakistani Sign Language (Pakistani SL is said to be R, but Indian SL to be A, though they are the same language), Japanese Sign Language, and maybe the various Thai Hill-Country sign languages, French Sign Language, Lyons Sign Language, and Nohya Maya Sign Language. Wittmann also includes, bizarrely, Chinese characters and Egyptian hieroglyphs.

- These are Providencia Island, Kod Tangan Bahasa Malaysia (manually signed Malay), German, Ecuadoran, Salvadoran, Gestuno, Indo-Pakistani (Pakistani SL is said to be R, but Indian SL to be A, though they are the same language), Kenyan, Brazilian, Spanish, Nepali (with possible admixture), Penang, Rennellese, Saudi, the various Sri Lankan sign languages, and perhaps BSL, Peruvian, Tijuana (spurious), Venezuelan, and Nicaraguan sign languages.

- Wittmann adds that this taxonomic criterion is not really applicable with any scientific rigor: Auxiliary sign languages, to the extent that they are full-fledged natural languages (and therefore included in his survey) at all, are mostly used by the deaf as well, and some primary sign languages (such as ASL and Adamorobe Sign Language) have acquired auxiliary usages.

- Wittmann includes in this class Australian Aboriginal sign languages (at least 14 different languages), Monastic sign language, Thai Hill-Country sign languages (possibly including languages in Vietnam and Laos), and Sri Lankan sign languages (14 deaf schools with different sign languages).

- Wittmann's references on the subject, besides his own work on creolization and relexification in spoken languages, include papers such as Fischer (1974, 1978), Deuchar (1987) and Judy Kegl's pre-1991 work on creolization in sign languages.

- Wittmann's explanation for this is that models of acquisition and transmission for sign languages are not based on any typical parent-child relation model of direct transmission which is inducive to variation and change to a greater extent. He notes that sign creoles are much more common than vocal creoles and that we can't know on how many successive creolizations prototype-A sign languages are based prior to their historicity.

- Brentari, Diane (1998) A prosodic model of sign language phonology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- Brentari, Diane (2002). "Modality differences in sign language phonology and morphophonemics". In P. Meier; Kearsy Cormier; David Quinto-Pozos (eds.). Modality and Structure in Signed and Spoken Languages. pp. 35–36. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486777.003. ISBN 9780511486777.

- Ulrike, Zeshan; Escobedo Delgado, Cesar Ernesto; Dikyuva, Hasan; Panda, Sibaji; de Vos, Connie (2013). "Cardinal numerals in rural sign languages: Approaching cross-modal typology". Linguistic Typology. 17 (3). doi:10.1515/lity-2013-0019. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-B2E1-B. S2CID 145616039.

- Emmorey, Karen (2002). Language, Cognition, and the Brain. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Mayberry, Rachel. "The Critical Period for Language Acquisition and The Deaf Child's Language Comprehension: A Psycholinguistic Approach" (PDF). ACFOS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-01.

- Reilly, Judy (2005). "How Faces Come to Serve Grammar: The Development of Nonmanual Morphology in American Sign Language". In Brenda Schick; Marc Marschack; Patricia Elizabeth Spencer (eds.). Advances in the Sign Language Development of Deaf Children. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press. pp. 262–290. ISBN 978-0-19-803996-9.

- Hopkins, Jason (2008). "Choosing how to write sign language: a sociolinguistic perspective". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2008 (192): 75–90. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.036. S2CID 145429638.

- Stokoe, William C.; Dorothy C. Casterline; Carl G. Croneberg. 1965. A dictionary of American sign language on linguistic principles. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet College Press

- Herrero Blanco, Ángel L. (2003). Escritura alfabética de la Lengua de Signos Española : once lecciones. Alfaro, Juan José,, Cascales, Inmaculada. San Vicente del Raspeig [Alicante]: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante. ISBN 9781282574960. OCLC 643124997.

- "Biblioteca de signos – Materiales". www.cervantesvirtual.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-06. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- "Traductor de español a LSE – Apertium". wiki.apertium.org. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- "Diccionario normativo de la lengua de signos española ... (SID)". sid.usal.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2019-07-07. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- Galea, Maria (2014). SignWriting (SW) of Maltese Sign Language (LSM) and its development into an orthography: Linguistic considerations (Ph.D. dissertation). Malta: University of Malta. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Ampessan, João Paulo. "The Writing of Grammatical Non-Manual Expressions in Sentences in LIBRAS Using the SignWriting System." Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 2015. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021.

- Morford, Jill P.; Staley, Joshua; Burns, Brian (Fall 2010). Videography by Jo Santiago and Brian Burns. "Seeing Signs: Language Experience and Handshape Perception" (PDF). Deaf Studies Digital Journal (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- Kuhl, P (1991). "Human adults and human infants show a 'perceptual magnet effect' for the prototypes of speech categories, monkeys do not". Perception and Psychophysics. 50 (2): 93–107. doi:10.3758/bf03212211. PMID 1945741.

- Morford, J. P.; Grieve-Smith, A. B.; MacFarlane, J.; Staley, J.; Waters, G. S. (2008). "Effects of language experience on the perception of American Sign Language". Cognition. 109 (41–53): 41–53. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2008.07.016. PMC 2639215. PMID 18834975.

- Woll, Bencie; Ladd, Paddy (2003), "Deaf communities", in Marschark, Marc; Spencer, Patricia Elizabeth (eds.), Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-195-14997-5

- McCaskill, C. (2011). The hidden treasure of Black ASL: its history and structure. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- Zeshan, Ulrike; de Vos, Connie (2012). Sign languages in village communities: Anthropological and linguistic insights. Berlin and Nijmegen: De Gruyter Mouton and Ishara Press.

- Kisch, Shifra (2008). ""Deaf discourse": The social construction of deafness in a Bedouin community". Medical Anthropology. 27 (3): 283–313. doi:10.1080/01459740802222807. hdl:11245/1.345005. PMID 18663641. S2CID 1745792.

- "Benefits of Sign Language and Other Forms of AAC for Autism". 3 June 2020.

- Looney, Dennis; Lusin, Natalia (February 2018). "Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Preliminary Report" (PDF). Modern Language Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-16.

- Sarah C. E. Batterbury. 2012. Language Policy 11:253–272.

- "ITC Guidelines on Standards for Sign Language on Digital Terrestrial Television". Archived from the original on 2007-04-23. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5241699de4b09847f93f8123/t/5fc407ad18e72e5fdb558e80/1606682553723/Sign+language+interpreting+on+TV+and+media-+sharing+best+practices+.pdf

- "Sign Language on Television". RNID. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Bell Laboratories RECORD (1969) A collection of several articles on the AT&T Picturephone Archived 2012-06-23 at the Wayback Machine (then about to be released) Bell Laboratories, Pg.134–153 & 160–187, Volume 47, No. 5, May/June 1969;

- Huang, Jie; Zhou, Wengang; Zhang, Qilin; Li, Houqiang; Li, Weiping (2018-01-30). Video-based Sign Language Recognition without Temporal Segmentation (PDF). 32nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-18), Feb. 2–7, 2018, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. arXiv:1801.10111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-29.

- Durr, Patti (2020). "Arnaud Balard". Deaf Art. National Technical Institute for the Deaf. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- Bickford, J. Albert, and Melanie McKay-Cody (2018). "Endangerment and revitalization of sign languages", pp. 255–264 in The Routledge handbook of language revitalization.

- "Did you know Hawai'i Sign Language is critically endangered?". Endangered Languages. Archived from the original on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. 2003-01-01. ISBN 9780195139778.

The language is considered to be endangered. 9,600 deaf people in Hawaii now use American Sign Language with a few local signs for place-names and cultural items.

- McKee, Rachel; McKee, David (2016), "Assessing the vitality of NZSL", 12th International Conference on Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research (PDF), Melbourne, Australia, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-01

- Bickford; Albert, J.; Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F. (2014). "Rating the vitality of sign languages". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36 (5): 1–15.

- Velupillai, Viveka (2012). An Introduction to Linguistic Typology. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 57–58. ISBN 9789027211989. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- "Sign languages in UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger Project". University of Central Lancashire. Retrieved 2021-08-23.

- MacDougall, Jamie (February 2001). "Access to justice for deaf Inuit in Nunavut: The role of "Inuit sign language"". Canadian Psychology. 41 (1): 61. doi:10.1037/h0086880.

- Zeshan, Ulrike. (2007). The ethics of documenting sign languages in village communities. In Peter K. Austin, Oliver Bond & David Nathan (eds) Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine London: SOAS. p. 271.

- Taylor-DiLeva, Kim. Once Upon A Sign : Using American Sign Language To Engage, Entertain, And Teach All Children, p. 15. Libraries Unlimited, 2011. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 29 Feb. 2012.

- Susan Goldin-Meadow (Goldin-Meadow 2003, Van Deusen, Goldin-Meadow & Miller 2001) has done extensive work on home sign systems. Adam Kendon (1988) published a seminal study of the homesign system of a deaf Enga woman from the Papua New Guinea highlands, with special emphasis on iconicity.

- The one possible exception to this is Rennellese Sign Language, which has the ISO 639-3 code [rsi]. It only ever had one deaf user, and thus appears to have been a home sign system that was mistakenly-accepted into the ISO 639-3 standard. It has been proposed for deletion from the standard. ("Change Request Number: 2016-002" (PDF). ISO 639-3. SIL International. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2016-07-05.)

- Premack and Premack, David and Ann J (1984). The Mind of an Ape (1st ed.). NY: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0393015812.

- Plooij, F.X. (1978) "Some basic traits of language in wild chimpanzees?" in A. Lock (ed.) Action, Gesture and Symbol New York: Academic Press.

- Nishida, T (1968). "The social group of wild chimpanzees in the Mahali Mountains". Primates. 9 (3): 167–224. doi:10.1007/bf01730971. hdl:2433/213162. S2CID 28751730.

- Premack, D (1985). "'Gavagai!' or the future of the animal language controversy". Cognition. 19 (3): 207–296. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(85)90036-8. PMID 4017517. S2CID 39292094.

- Gardner, R.A.; Gardner, B.T. (1969). "Teaching Sign Language to a Chimpanzee". Science. 165 (3894): 664–672. Bibcode:1969Sci...165..664G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.4164. doi:10.1126/science.165.3894.664. PMID 5793972.

- Gardner, R.A., Gardner, B.T., and Van Cantfort, T.E. (1989), Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees, Albany: SUNY Press.

- Terrace, H.S. (1979). Nim: A chimpanzee who learned Sign Language New York: Knopf.