Eilat

Eilat (/eɪˈlɑːt/ ay-LAHT, UK also /eɪˈlæt/ ay-LAT; Hebrew: אֵילַת [eˈlat] (![]() listen); Arabic: إِيلَات, romanized: Īlāt) is Israel's southernmost city, with a population of 52,299,[1] a busy port and popular resort at the northern tip of the Red Sea, on what is known in Israel as the Gulf of Eilat and in Jordan as the Gulf of Aqaba. The city is considered a tourist destination for domestic and international tourists heading to Israel.

listen); Arabic: إِيلَات, romanized: Īlāt) is Israel's southernmost city, with a population of 52,299,[1] a busy port and popular resort at the northern tip of the Red Sea, on what is known in Israel as the Gulf of Eilat and in Jordan as the Gulf of Aqaba. The city is considered a tourist destination for domestic and international tourists heading to Israel.

Eilat

אילת إيلات | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)   From upper left: Eilat coastline at night (×2), evening view of Eilat marina, view of Eilat North Beach, view from the promenade to the outskirts and the surrounding mountains of Eilat. | |

Flag  Emblem of Eilat | |

Eilat  Eilat | |

| Coordinates: 29°33′25″N 34°57′06″E | |

| Country | |

| District | Southern |

| Founded | 7000 BCE (Earliest settlements) 1951 (Israeli city) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Meir Yitzhak Halevi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 84,789 dunams (84.789 km2 or 32.737 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 52,299 |

| • Density | 620/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| Website | www.eilat.muni.il |

Eilat is part of the Southern Negev Desert, at the southern end of the Arabah, adjacent to the Egyptian resort city of Taba to the south, the Jordanian port city of Aqaba to the east, and within sight of Haql, Saudi Arabia, across the gulf to the southeast.

Eilat's arid desert climate and low humidity are moderated by proximity to a warm sea. Temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in summer, and 21 °C (70 °F) in winter, while water temperatures range between 20 and 26 °C (68 and 79 °F). Eilat averages 360 sunny days a year.[2]

Name

The name Eilat was given to Umm al-Rashrāsh (أم الرشراش) in 1949 by the Committee for the Designation of Place-Names in the Negev. The name refers to Elath, a location mentioned in the Hebrew Bible that is thought to be located across the border in modern Jordan. The committee acknowledged that Biblical Eilat/Elath was across the border; one committee member, Yeshayahu Press, justified the co-opting of the name by stating "when the real Eilat finally is in our hands, our settlement will expand and reach over to there."[3]

Geography

The geology and landscape are varied: igneous and metamorphic rocks, sandstone and limestone; mountains up to 892 metres (2,927 ft) above sea level; broad valleys such as the Arava, and seashore on the Gulf of Aqaba. With an annual average rainfall of 28 millimetres (1.1 in) and summer temperatures of 40 °C (104 °F) and higher, water resources and vegetation are limited. "The main elements that influenced the region's history were the copper resources and other minerals, the ancient international roads that crossed the area, and its geopolitical and strategic position. These resulted in a settlement density that defies the environmental conditions."[4]

History

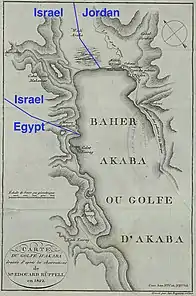

Historical "Elath" / Ayla is located at Aqaba, in Jordan; the Israeli map includes the words Hebrew: אֵילַת הרומאית, lit. 'Roman Eilat'. The mound shown on the 1822 map as "Ruines d'Elana" is today known as Tell el-Kheleifeh, speculated to be Biblical Ezion-Geber; it is shown on the Israeli map as Hebrew: עֶצְיֹן גֶּבֶר, lit. 'Ezion-Geber'. The mountain peak named "Gebel Gatal Mahamar" in 1822 is named Hebrew: הַר שְׁלֹמֹה, lit. 'Mount Solomon' in the Israeli map

Early history

Archaeological excavations uncovered impressive prehistoric tombs dating to the 7th millennium BC at the western edge of Eilat, while nearby copper workings and mining operations at Timna Valley are the oldest on earth.

An Islamic copper smelting and trading community of 250–400 residents flourished in the area during the Umayyad Period (700–900 CE); its remains were found and excavated in 1989, at the northern edge of modern Eilat, between what is now the industrial zone and nearby Kibbutz Eilot.[5]

Modern city

During the British Mandate era, a British police post existed in the area, which was known as Umm Al-Rashrash. The area was designated as part of the Jewish state in the 1947 UN Partition Plan. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the abandoned police post, which consisted of five clay huts, was taken without a fight on March 10, 1949, as part of Operation Uvda.[6][7] This marked the end of Israel's war for independence.

The town developed over the following years. Eilat Airport was built in 1949 and individual ships began arriving in the 1950s, but as there were no dedicated port facilities they unloaded their goods at sea. In the early 1950s, Eilat was a small and remote town, populated largely by port workers, soldiers, and former prisoners. The town's development accelerated in 1955, when it had a population of about 500. The Timna Copper Mines[8] near the Timna Valley and the Port of Eilat were opened that year and concerted effort by the Israeli government to populate Eilat began, starting with Jewish immigrant families from Morocco being resettled there. Eilat began to develop rapidly after the Suez Crisis in 1956, with its tourism industry in particular starting to flourish. The Israeli Navy's Eilat naval base was founded that year.[9] The town's population grew to 5,300 in 1961. Yoseftal Medical Center and the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline were completed in 1968, and the population increased further, reaching 13,100 in 1972 and 18,900 in 1983.

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War Arab countries maintained a state of hostility with Israel, blocking all land routes; Israel's access to and trade with the rest of the world was by air and sea alone. Further, Egypt denied passage through the Suez Canal to Israeli-registered ships or to any ship carrying cargo to or from Israeli ports. This made Eilat and its sea port crucial to Israel's communications, commerce and trade with Africa and Asia, and for oil imports. Without recourse to a port on the Red Sea Israel would have been unable to develop its diplomatic, cultural and trade ties beyond the Mediterranean basin and Europe. This happened in 1956 and again in 1967, when Egypt's closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping effectively blockaded the port of Eilat.

In 1956, this led to Israel's participation alongside Britain and France in the war against Egypt sparked by the Suez Crisis, while in 1967 90% of Israeli oil passed through the Straits of Tiran.[10] Oil tankers that were due to pass through the straits were delayed.[11][12] The straits' closure was cited by Israel as an additional casus belli leading to the outbreak of the Six-Day War. Following peace treaties signed with Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994, Eilat's borders with its neighbors were finally opened.

.jpg.webp)

Israeli–Arab conflict

Eilat is especially defended by its own special forces unit Lotar Eilat. It is a reservist special forces unit of the IDF trained in counter-terrorism and hostage rescue in the Eilat area, which has taken part in many counter-terrorist missions in the region since its formation in 1974. The Lotar unit is composed solely of reservists, citizens who must be Eilat residents between the ages of 20 and 60, who are on call in case of a terrorist attack on the city. It is one of only three units in the IDF authorized to free hostages on its own command.[13][14] In 2007 the Eilat bakery bombing killed three civilian bakers.[15][16] This was the first such attack in Eilat proper,[17] although other terror attacks had been carried out in the area.[18]

In 2011, terrorists infiltrated Israel across the Sinai border to execute multiple attacks on Highway 12, including a civilian bus and private car a few miles north of Eilat, in what became known as the 2011 southern Israel cross-border attacks.[19][20]

In order to prevent terrorist infiltration of Israel from the Sinai, Israel has built the Egypt–Israel barrier, a steel barrier equipped with cameras, radar and motion sensors along the country's southern border.[21] The fence was completed in January 2013.[22]

Future development plans

In July 2012, Israel signed an agreement with China to cooperate in building the high-speed railway to Eilat, a railway line which will serve both passenger and freight trains. It will link Eilat with Beersheba and Tel Aviv, and will run through the Arava Valley and Nahal Zin.[23]

The former Eilat Airport was closed on 18 March 2019 after the opening of Ramon Airport. The land occupied by the former airport is to be redeveloped. The new Ramon Airport opened in January 2019, 18 kilometres (11 miles) north of Eilat and replaced both Eilat Airport and the civilian use of Ovda Airport.[24] Hotels and apartment buildings, containing a total of 2,080 hotel rooms and 1,000 apartments will be constructed on the site, as well as 275 dunams of public space and pedestrian paths. The plans also set aside space for the railway line and an underground railway station. The plan's goal is to create an urban continuum between the city center and North Beach, as well as tighten the links between the city's neighborhoods, which were separated by the airport.[25]

In addition, there are plans to move the Port of Eilat and the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline terminal to the northern part of the city, as well as to turn it into a university town of science and research, and brand it an international sports city. All these projects are part of a plan to increase Eilat's population to 150,000 people and build 35,000 hotel rooms.[26]

Climate

Eilat has a hot desert climate (BWh[27] with hot, dry summers and warm and almost rainless winters in Köppen climate classification). Winters are usually between 11–23 °C (52–73 °F). Summers are usually between 26–40 °C (79–104 °F). There are relatively small coral reefs near Eilat; however, 50 years ago they were much larger.

| Climate data for Eilat (Temperature: 1987–2010, Precipitation: 1980–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.2 (90.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

43.4 (110.1) |

45.2 (113.4) |

47.4 (117.3) |

48.3 (118.9) |

48.0 (118.4) |

45.0 (113.0) |

44.3 (111.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

33.6 (92.5) |

48.3 (118.9) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

29.3 (84.7) |

32.8 (91.0) |

38.2 (100.8) |

42.1 (107.8) |

43.6 (110.5) |

44.1 (111.4) |

43.2 (109.8) |

41.9 (107.4) |

39.7 (103.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

44.1 (111.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.7 (96.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

40.4 (104.7) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.3 (99.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

31.5 (88.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.7 (92.7) |

31.3 (88.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.9 (53.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.3 (41.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.9 (33.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 4 (0.2) |

3 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (0.2) |

2 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

24 (1) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 10.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 32 | 28 | 25 | 19 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 23 | 27 | 29 | 33 | 24 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 229.4 | 237.3 | 251.1 | 273 | 319.3 | 324 | 347.2 | 347.2 | 291 | 282.1 | 246 | 217 | 3,364.6 |

| Source: Israel Meteorological Service[28][29][30][31] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 °C (72 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) |

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 500 | — |

| 1961 | 5,300 | +960.0% |

| 1972 | 13,100 | +147.2% |

| 1983 | 18,900 | +44.3% |

| 1995 | 32,500 | +72.0% |

| 2008 | 47,300 | +45.5% |

| 2017 | 50,724 | +7.2% |

| Source: CBS[33] | ||

The overwhelming majority of Eilat's population are Jews. Arabs constitute about 4% of the population.[34] Eilat's population includes a large number of foreign workers, estimated at over 10,000 working as caregivers, hotel workers and in the construction trades. Eilat also has a growing Israeli Arab population, as well as many affluent Jordanians and Egyptians who visit Eilat in the summer months.

In 2007, over 200 Sudanese refugees from Egypt who arrived in Israel illegally on foot were given work and allowed to stay in Eilat.[35][36][37]

Education

The educational system of Eilat accommodates more than 9,000 youngsters in eight day-care centers, 67 pre-kindergartens and kindergartens, 10 elementary schools, and 3 six-year high schools. Also, there are some special-education schools and religious schools.[38] Ben Gurion University of the Negev maintains a campus in Eilat. The Eilat branch has 1,100 students, about 75 percent from outside the city. In 2010, a new student dormitory was funded and built by the Jewish Federation of Toronto, the Rashi Foundation, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and the municipality of Eilat.[39] The SPNI's Eilat Field School on the outskirts of Eilat offers special hiking tours that focus on desert ecology, the Red Sea, bird migration and other aspects of Eilat's flora and fauna.[40] The Hesder Yeshiva Ayelet Hashachar, is based in Eilat, established in 1997.[41]

Healthcare

Yoseftal Medical Center, established in 1968, is Israel's southernmost hospital, and the only hospital covering the southern Negev. With 65 beds, the hospital is Israel's smallest. Special services geared to the Red Sea region are a hyperbaric chamber to treat victims of diving accidents and kidney dialysis facilities open to vacationing tourists.[42]

Transportation

Air

Since 2019, Ramon International Airport has handled commercial domestic and international flights to Eilat (IATA: ETM, ICAO: LLER).

Former airports

- Eilat Airport is located in the city centre and was used largely for domestic flights[43] (IATA: ETH, ICAO: LLET). The former site is to be redeveloped.

- International flights often used Ovda International Airport some 50 kilometres (31 mi) northwest of the city[44] (IATA: VDA, ICAO: LLOV). While no civilian flights use the airport any longer, it remains in use as a military airbase and for aircraft storage.

Road

Eilat has two main roads connecting it with the center of Israel - Route 12, which leads North West, and Route 90 which leads North East, and South West to the border crossing with Egypt.

Bus

Egged, the national bus company, provides regular service to points north on an almost hourly basis as well as in-city on a half-hourly basis during daylight hours. In part due to the comparatively long travel times, there are different booking procedures for buses to Eilat, including the option of advance reservations.[45][46][47]

Border crossings with Egypt and Jordan

- The Taba Border Crossing allows crossing to and from Taba, Egypt.

- The Wadi Araba Crossing, renamed the Yitzhak Rabin Border Crossing on the Israeli side, allows crossing to and from Aqaba, Jordan.

Maritime

The Port of Eilat and Eilat Marina allow travel by sea.

Rail

Future plans also call for a rail link, sometimes referred to as the Med-Red[48] to decrease travel times substantially from Eilat to Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, via the existing line at Beer Sheba; planning is underway. As of 2021 Dimona railway station is the southernmost passenger train station in Israel.[49]

Economy

In the 1970s tourism became increasingly important to the city's economy as other industries shut down or were drastically reduced. Today tourism is the city's major source of income, although Eilat became a free trade zone in 1985.[50]

Tourism

Eilat offers a wide range of accommodations, from hostels and luxury hotels to Bedouin hospitality. In recent years Eilat has been the target of militants from Egypt and Gaza causing a reduced tourist inflow to the region. Attractions include:

- Birdwatching and ringing station: Eilat is located on the main migration route between Africa and Europe. International Birding & Research Center in Eilat.[51]

- Camel tours

- Coral Beach Nature Reserve, an underwater marine reserve of tropical marine flora and fauna

- Coral World Underwater Observatory, located at the southern tip of Coral Beach, it has aquaria, a museum, simulation rides, and shark, turtle, and stingray tanks. The observatory is the biggest public aquarium in the Middle East.[52]

- Dolphin Reef, a marine biology and research station where visitors can swim and interact with dolphins[53]

- Freefall parachuting.

- Yotvata Hai-Bar Nature Reserve, established in the 1960s to conserve endangered species, including Biblical animals, from this and similar regions. The reserve has a visitors' center, care and treatment enclosures, and large open area where desert animals are acclimated before re-introduction into the wild. Hai-Bar efforts have successfully re-introduced the Asian wild ass, or onager, into the Negev.[54] The Hai-Bar Nature Reserve and animal re-introduction program were described in Bill Clark's book "High Hills and Wild Goats: Life Among the Animals of the Hai-Bar Wildlife Refuge". The book also describes life in Eilat and the surrounding area.[55]

- Marina, with some 250 yacht berths

- Timna Valley Park, the oldest copper mines in the world; Egyptian temple of Hathor, King Solomon's Pillars sandstone formation, ancient pit mines and rock art[56]

- "What's Up", a portable astronomical observatory with programs in the desert and on the promenade[57]

- Ice Mall, ice skating rink and shopping mall

Dive tourism

Skin and scuba diving equipment is for hire on or near all major beaches. Scuba diving equipment rental and compressed air are available from diving clubs and schools all year round. Eilat is located in the Gulf of Aqaba, one of the most popular diving destinations in the world. The coral reefs along Eilat's coast remain relatively pristine and the area is recognized as one of the prime diving locations in the world.[58] About 250,000 dives are performed annually in Eilat's 11 km (6.8 mi) coastline, and diving represents 10% of the tourism income of this area.[59] In addition, given the proximity of many of these reefs to the shore, non-divers can encounter the Red Sea's reefs with relative ease.[58] Water conditions for SCUBA divers are good all year round, with water temperatures around 21–25 °C (70–77 °F), with little or no currents and clear waters with an average of 20–30 metres (66–98 feet) visibility.

Museums

- Eilat City Museum

- Eilat Art Gallery

Film

Eilat has been utilized by film and television productions - domestic and foreign - for location shooting since the 1960s, most notably in the early 90s as a tropical locale for season 2 of the Canadian production Tropical Heat.

It was also used in the films She, Madron, Ashanti and Rambo III.

Archaeology

Despite harsh conditions, the region has supported large populations as far back as 8,000 BCE.

Exploration of ancient sites began in 1861, but only 7% of the area has undergone serious archaeological excavation. Some 1,500 ancient sites are located in a 1,200-square-kilometer (460 sq mi) area. In contrast to the gaps found in settlement periods in the neighbouring Negev Highlands and Sinai, these sites show continuous settlement for the past 10,000 years.

Notable people

- Shawn Dawson (born 1993), basketball player

- Gadi Eizenkot (born 1960), Chief of General Staff of the Israel Defense Forces

- Eden Harel (born 1976), actress

- Amit Ivry (born 1989), Olympic swimmer and national record holder

- Keren Karolina Avratz (born 1971), singer, songwriter

- Shaul Mofaz (born 1948), former Minister of Defense, former Chief of General Staff of the Israel Defense Forces

- Ziki Shaked (born 1955), first Israeli ship's captain to go around the world under the Israeli flag, from Eilat to Eilat

- Shahar Tzuberi (born 1986), Israeli Olympic bronze-medal-winning windsurfer, 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing

- Raviv Ullman (born 1986), Israeli-American actor, musician

- Ghil'ad Zuckermann (born 1971), linguist, with a focus on language revitalization

Twin towns – sister cities

Acapulco, Mexico

Acapulco, Mexico Antibes, France

Antibes, France Arica, Chile

Arica, Chile Durban, South Africa

Durban, South Africa Kamen, Germany

Kamen, Germany Kampen, Netherlands

Kampen, Netherlands Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic

Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic Los Angeles, United States

Los Angeles, United States Palanga, Lithuania

Palanga, Lithuania Piešťany, Slovakia

Piešťany, Slovakia Sopron, Hungary

Sopron, Hungary Sorrento, Italy

Sorrento, Italy Yalta, Ukraine

Yalta, Ukraine Yinchuan, China

Yinchuan, China Ushuaia, Argentina

Ushuaia, Argentina

Eilat has streets named after Antibes, Durban, Kamen, Kampen and Los Angeles as well as a Canada Park.

Panoramic views

See also

- Bnei Eilat F.C.

- Eilat Pride

- Eilat Sports Center

- Eilat stone

- Hapoel Eilat B.C.

- Operation Ovda

- Red Sea Jazz Festival

- Yotvata Airfield

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Discovering the World of the Bible, LaMar C. Berrett, (Cedar Fort 1996), page 204

- Eretz Magazine (3 June 2018), Editorial, The Names Committee Archived 2020-09-22 at the Wayback Machine: "The issue of Eilat took up another chunk of the committee’s time. In 1949, Eilat did not exist. The city was founded only in 1952. But a place by the name of Eilat appears time and again in the biblical record. It was one of the stations in the wanderings of the people of Israel during the exodus from Egypt. King Solomon built ships on the shore of the Sea of Sof, in the land of Edom at Etzion Gever, which is Eilat. King Azariya of Judah built the city of Eilat, and so on and so forth. However, the location of this place called Eilat or Etzion Gaver remained unclear. On the shore of the gulf, where the big shopping mall of Eilat is today, a small adobe hut stood. The hut served as a British police station called Umm Rashrash. “On the map,” Yeivin explained, “we see a place called Umm Rashrash and next to it the name Eilat. But Eilat was not here. Biblical and Roman Eilat were across the border in Jordan. The name Eilat should be erased from the map.”; “We cannot give up Eilat,” Press retorted, “when the real Eilat finally is in our hands, our settlement will expand and reach over to there.” David Amiran, the geographer, suggested that Eilat should be the name of the settlement that would be built on the shore of the gulf, which should be called the Gulf of Eilat. Ben-Zvi was for eliminating Umm Rashrash from the map together with Etzion Gaver. Eilat is Eilat, he said, musing that maybe the committee should call Umm Rashrash Etzion Gaver and establish Eilat elsewhere. The committee ultimately decided to replace the name Umm Rashrash with Eilat. Etzion Gaver was commemorated on the map by dubbing a well along the coast Be’er Etzion Gever. Today the well is buried under the artificial lagoon in Eilat."

- Avner, U. 2008. Eilat Region. In, A. Stern (ed.). The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavation in the Holy Land, Volume 5 (Supplementary). Jerusalem. 1704–1711.

- Yehudah Rapuano (2013). "An Early Islamic Settlement and a Possible Open-Air Mosque at Eilat". 'Atiqot. 75: 129–165.

- John S. Haupert (1964). "Development of Israel's Frontier Port of Elat". The Professional Geographer. 16 (2): 13–16. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1964.00013.x.

- Nowar, Maan Abu (2002). The history of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (1. ed.). Oxford: Ithaca Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-0863722868. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- "Timna Copper Mines homepage". Archived from the original on 2016-04-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Untitled | דבר | 27 דצמבר 1956 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". www.nli.org.il.

- Avi Shlaim; William Roger Louis (13 February 2012). The 1967 Arab-Israeli War: Origins and Consequences. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-107-00236-4. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

90% of Israeli oil was imported through the Straits of Tiran

- Avi Shlaim; William Roger Louis (13 February 2012). The 1967 Arab-Israeli War: Origins and Consequences. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-107-00236-4. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- "Daily brief to the U.S president on 27 May 1967" (PDF). 27 May 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

"diverted as was a sister ship yesterday

- The real 24: An inside look at an elite IDF anti-terror unit Archived 2015-07-02 at the Wayback Machine Friday August 26, 2011

- "5 Things You Didn't Know about the Eilat Counterterrorism Unit". Archived from the original on 2016-02-20. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- Suicide Bomb Kills 3 in Bakery in Israel Archived 2018-12-15 at the Wayback Machine – The New York Times, Jan 29, 2007

- "Eilat driver warned police about terrorist minutes before attack". Haaretz. April 17, 2006. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- "Peretz orders IDF to prepare for operations in Gaza". The Jerusalem Post. January 29, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- "Past terror attacks in the Eilat area". Haaretz. January 29, 2007. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- Harel, Amos (September 2, 2011). "September songs". Haaretz. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- Wyre Davies (August 2, 2010). "'One killed' after rockets strike Jordan and Israel". BBC. Archived from the original on September 16, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- Joel Greenberg (2011-12-02). "On Israel's uneasy border with Egypt, a fence rises". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Amos Harel (2011-11-13). "On Israel-Egypt border, best defense is a good fence". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- "Israel, China agree to build Eilat railway". Globes. 2012-07-03. Archived from the original on 2013-08-08. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "Ramon Airport". Ramon Airport Website. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- "Hotels, 1,000 apartments planned for Eilat Airport site". Globes. 2012-04-03. Archived from the original on 2013-01-08. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "Despite Japan, IEC chairman urges nuclear power". Globes. 2011-03-15. Archived from the original on 2011-03-25. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "Climate: Eilat - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Averages and Records for Tel Aviv (Precipitation, Temperature and Records written in the page)". Israel Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.(in Hebrew)

- "Extremes for Tel Aviv [Records of February and May]". Israel Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.(in Hebrew)

- "Temperature average". Israel Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2011.(in Hebrew)

- "Precipitation average". Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.(in Hebrew)

- "Eilat Climate and Weather Averages, Israel". Weather2Travel. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- "Locality File". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2012. Archived from the original (XLS) on 2013-11-03. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "The Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research Weblog: "Mixed Cities" in Israel". 2013-11-11. Archived from the original on 2018-10-28. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- Jonathan Saul, Elana Ringler for Reuters (2007). "Sudanese refugees in Israel face uncertainty". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- Joshua Mitnick (2006). "Sudan's "Genocide" Lands at Israel's Door". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- Neta Sela (2007). "Israel must reject Darfur refugees, rabbi says". Ynetnews. Ynet News – Jewish World. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- Daniel Horowitz. "UJA Federation of Greater Toronto". Jewishtoronto.net. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- "New Student Dormitories Dedicated in Eilat Campus". 2010-05-15. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- "SPNI field schools". Aspni.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- site of the Yeshiva Archived 2019-12-24 at the Wayback Machine/

- "Clalit Health Services". Clalit.org.il. Archived from the original on February 16, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- Israel Airports Authority (2007). "Eilat Airport". Israel Airports Authority. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- Israel Airports Authority (2007). "Ovda Airport". Israel Airports Authority. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- "Advance booking - egged.co.il".

- "The Bus to Eilat". The New Yorker. 18 August 2011.

- "Tourist Tip #152 / Taking the Bus to Eilat". Haaretz.

- Moti Bassok, Cabinet examining plan for Med-Red railway Archived 2014-02-15 at the Wayback Machine Haaretz, January 30, 2012

- "Israel Railways rides again but few passengers return". Globes. 28 June 2020.

- Maltz, Judy (January 12, 1989). "Eilat turns to industry to complement tourism trade". The Jerusalem Post. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- "birdsofeilat.com". birdsofeilat.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- Coral World (2005). "The Underwater Observatory Marine Park, Eilat". Coral World. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- The Dolphin Reef Eilat (2007). "The Freedom To Choose". The Dolphin Reef Eilat. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- The Red Sea Desert (2007). "Hai-Bar Yotvata Nature Reserve". The Red Sea Desert. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- Bill clark (1989). "High Hills and Wild Goats: Life Among the Animals of the Hai-Bar Wildlife Refuge". Little Brown and Company; 1st edition. Archived from the original on 2010-11-09. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- BiblePlaces.com (2007). "Timna Valley". BiblePlaces.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ""What's Up" Observatory in Eilat". Whatsup.eilatnature.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- "MFA, Gulf of Aqaba- Tourism, 30 Sep 1997". Mfa.gov.il. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- Artificial Reefs and Dive Tourism in Eilat, Israel Dan Wilhelmsson, Marcus C. Öhman, Henrik Ståhl and Yechiam Shlesinger Ambio, Vol. 27, No. 8, Building Capacity for Coastal Management (Dec., 1998), pp. 764–766 Published by: Allen Press on behalf of Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Archived 2016-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- "ערים תאומות". eilat.muni.il (in Hebrew). Eilat. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

External links

- Eilat + official tourism website of the city of Eilat

- Official city site (in Hebrew)

- Crossing the Israel – Jordan Border

- Eilat Tourist directory

- A film about Eilat in 1960 commentary (in Hebrew)

- Photos of Eilat

- Tourism city guide site

- Eilat Today, a magazine of current affairs

- Birding in Eilat

- Scuba Diving in Eilat with descriptions of dive sites

.jpg.webp)