Fantastic Universe

Fantastic Universe was a U.S. science fiction magazine which began publishing in the 1950s. It ran for 69 issues, from June 1953 to March 1960, under two different publishers. It was part of the explosion of science fiction magazine publishing in the 1950s in the United States, and was moderately successful, outlasting almost all of its competitors. The main editors were Leo Margulies (1954–1956) and Hans Stefan Santesson (1956–1960); under Santesson's tenure the quality declined somewhat,[1] and the magazine became known for printing much UFO-related material. A collection of stories from the magazine, edited by Santesson, appeared in 1960 from Prentice-Hall, titled The Fantastic Universe Omnibus.

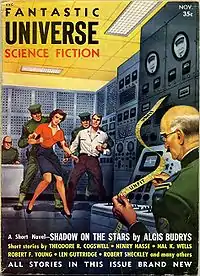

November 1954 issue; cover by Alex Schomburg | |

| Editor | Sam Merwin |

|---|---|

| Editor | Beatrice Jones |

| Editor | Leo Margulies |

| Editor | Hans Stefan Santesson |

| Categories | Science fiction magazine |

| Frequency | bimonthly |

| Publisher | Leo Margulies, H.L. Herbert |

| First issue | June–July 1953 |

| Final issue Number | March 1960 Volume 12 No 5 |

| Company | King-Size Publications, Great American Publications |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Publication history

The early 1950s saw dramatic changes in the world of U.S. science fiction publishing. At the start of 1949, all but one of the major magazines in the field were in pulp format; by the end of 1955, all had either ceased publication or switched to digest format.[2] This change was largely the work of the distributors, such as American News Company, who refused to carry the pulp magazines since they were no longer profitable;[3] the loss of profitability was in turn associated with the rise in mass-market science fiction publishing, with paperback publishers such as Ace Books and Ballantine Books becoming established.[4] Along with the increase in science fiction in book form came a flood of new U.S. magazines: from a low of eight active magazines in 1946, the field expanded to twenty in 1950, and a further twenty-two had commenced publication by 1954.[5]

Fantastic Universe published its first issue in the midst of this publishing boom. The issue, published in digest format, was dated June–July 1953, and was priced at 50 cents. This was higher than any of its competition, but it also had the highest page count in the field at the time, with 196 pages. The initial editorial team was Leo Margulies as publisher, and Sam Merwin as editor; this was a combination familiar to science fiction fans from their years together at Thrilling Wonder Stories, which Merwin edited from 1945 to 1951. The publisher, King-Size Publications, also produced The Saint Detective Magazine, which was popular, so Fantastic Universe enjoyed good distribution from the start—a key factor in a magazine's success. The first issue included stories by Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and Ray Bradbury. According to Donald Tuck, the author of an early SF encyclopaedia, the magazine kept a fairly high quality through Merwin's departure after a year, and through the subsequent brief period of caretaker editorship by Beatrice Jones.[1][6][7] Margulies took over the editor's post with the May 1954 issue.[6][7]

In October 1955, Hans Stefan Santesson, an American writer, editor, and reviewer, began contributing "Universe in Books", the regular book review column. A year later, with the September 1956 issue, Santesson took over from Margulies as editor. One immediate change was an increase in the number of articles about UFOs. Santesson ran several articles by Ivan T. Sanderson, among others, including articles on auras and on the abominable snowman. However, he also ran polemical articles opposed to the UFO mania, including strongly worded pieces by Lester del Rey and C.M. Kornbluth. Del Rey, at least, felt that Santesson was not a believer in UFOs: "So far as I could determine, Santessen [sic] was skeptical about such things, but felt that all sides deserved a hearing and also that the controversies were good for circulation."[8][9]

The quality of the fiction is thought by Donald Tuck to have generally fallen during Santesson's period at the helm,[1] though this was not entirely his fault—there were a great many other magazines competing for stories by the top writers. Santesson himself, despite a modicum of controversy over his heavy use of UFO and related material, was kind and helpful to writers, and was well liked as a result.[10]

In late 1959 the magazine was sold to Great American Publications, and it was significantly redesigned. The size was increased to that of a glossy magazine, although the magazine was still bound rather than saddle-stapled. Under King-Size Publications, the magazine had had no artwork except small "filler" illustrations; now interior illustrations complementing the stories were introduced, and photographs and diagrams accompanied some of the articles. A fan column, by Belle C. Dietz, began, and Sam Moskowitz wrote two detailed historical articles about proto-sf. However, the March 1960 issue was the last one. Fredric Brown's "The Mind Thing" had begun serialization in that issue; it was eventually published in book form later that year.[6][10]

Circulation figures for Fantastic Universe are unknown, since at that time circulation figures were not required to be published annually, as they were later.[11] After the magazine folded, the publisher entertained plans to publish material bought for the magazine as a one-shot issue to be titled "Summer SF"; however, the issue never appeared.[10] Santesson did later edit an anthology drawn from the magazine, titled The Fantastic Universe Omnibus.[6][12]

Contents

Fantastic Universe published several significant stories during its seven-year history. These included stories from Tales of Conan, a collection of four Robert E. Howard stories rewritten as Conan stories by L. Sprague de Camp. Three of the stories were published in Fantastic Universe, two before the book, and one after:[13]

- "Hawks Over Shem" (October 1955)

- "The Road of the Eagles" (as "Conan, Man of Destiny", December 1955)

- "The Blood-Stained God" (April 1956)

Other notable and widely reprinted stories included:[14]

- "Short in the Chest", by Margaret St. Clair (writing as Idris Seabright, July 1954).

- "Who?", by Algis Budrys (April 1955). Formed the basis for Budrys's novel, Who?

- "The Minority Report", by Philip K. Dick (January 1956). The basis for the movie Minority Report.

- "First Law", by Isaac Asimov (October 1956). One of Asimov's robot stories.

- "Curative Telepath", by John Brunner (December 1959). Formed the basis of Brunner's novel The Whole Man.

- "The Large Ant", by Howard Fast (February 1960).

Other writers who appeared in the magazine included Harlan Ellison, Theodore Sturgeon, Robert Silverberg, Clifford Simak, Robert F. Young, and Robert Bloch.[9]

One offbeat feature of the magazine was the habit of including very short (less than a page) vignettes of fiction, usually but not always relating to the cover, without credit. These were most probably the work of the editor in many cases, though Frank Belknap Long wrote several of these for the inside front cover of the magazine. There was never a letter column, though in the last issue there was a note that one was planned for future issues. The book review column, always titled "Universe in Books", appeared fairly regularly but was liable to be dropped if there was no room for it. It was originally signed "The Editor", and was presumably written by Sam Merwin; Robert Frazier took the column on when Merwin left at the end of 1953. Santesson took over in October 1955 and wrote every column that appeared from that point on. After the first few issues, which contained editorial essays from both editor and publisher, the editorials disappeared, though Santesson did sometimes fill a blank space with a few editorial comments.[9]

Two articles by Moskowitz in the last few months of the magazine, "Two Thousand Years of Space Travel", and "To Mars and Venus in the Gay Nineties", were unusually early and well-researched articles on proto-science fiction. A couple of other non-fiction articles appeared late on, but with the exception of UFO-related material, and occasional filler paragraphs reporting science news, Fantastic Universe did not generally run science-related articles.[9]

Bibliographic details

The magazine began as a fat 196-page digest, priced at 50 cents, but this experiment did not last. The fourth issue, January 1954, cut the price to 35 cents, and it stayed at that price for the rest of its life. The page count also dropped, to 164 pages with the fourth issue, then to 132 pages with the eighth issue, September 1954. The page count stayed at 132 through the rest of the digest period, and for the first five issues of the "glossy" period under the new publisher. The last issue cut the page count to 100 pages.[6][9]

The magazine was initially bimonthly. The first three issues were named with two months: "June–July 1953", and so on. At the end of 1953 the naming was changed to the odd numbered months; and then after January, March, May, and July, the magazine went monthly, starting with the September 1954 issue. This lasted without a break until the November 1958 issue. Another bimonthly schedule, starting with January 1959, followed; the last King-Size Publications issue was September 1959, and it was followed by an October 1959 issue from Great American. The remaining five issues followed a regular monthly schedule; the last issue was March 1960. The volume numbering scheme was fairly regular; the first five volumes had six numbers each. Volume 6 had only five numbers, in order to get the new volume 7 to start with the new year, in 1957. This lasted until volume 10 was cut short at five numbers when the magazine returned to a bimonthly schedule at the end of 1958. Volume 11 had six numbers; volume 12 had five.[6][9]

The editors were:[6]

- June–July 1953 to October–November 1953: Sam Merwin Jr. (3 issues)

- January 1954 to March 1954: Beatrice Jones (2 issues)

- May 1954 to August 1956: Leo Margulies (26 issues)

- September 1956 to March 1960: Hans Stefan Santesson (38 issues)

Cover art was initially mostly by Alex Schomburg. Other artists, including Ed Emshwiller, Kelly Freas, and Mel Hunter, contributed covers; and towards the end there was a long sequence of covers by Virgil Finlay. Finlay also contributed much of the interior art in the last six issues; generally Great American did not credit the artists, but along with Finlay, Emshwiller and John Giunta were featured.[6][9]

Notes

- Tuck comments that the magazine was at first "of quite [a] reasonable standard" but "fell off considerably". See Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc. p. 561. ISBN 0-911682-26-0. John Clute says "Some magazines never seem to ... publish much worthwhile material" and then adds "Fantastic Universe, which published second-rank work by many well-known writers, is one of these." See Clute, John (1995). Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 103. ISBN 0-7894-0185-1. Brian Stableford refers to the magazine as "the poor man's F&SF". See Nicholls, Peter, ed. (1981). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Frogmore: Granada Publishing. p. 209. ISBN 0-586-05380-8.

- Some minor magazines such as Other Worlds remained, briefly, in pulp format. See Ashley, Michael (1976). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 3 1946–1955. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. p. 106. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- Ashley, Michael (1976). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 3 1946–1955. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. p. 88. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter, eds. (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. p. 979. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- Magazine publishing dates for the period are tabulated in Ashley, Michael (1976). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 3 1946–1955. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. pp. 323–325. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc. pp. 560–561. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.

- The page count, 196, includes the front and back covers, both inside and out; printed material, occasionally including fiction, did appear in these locations. Reference works that quote 192 pages for the magazine, as Ashley does, are following the page numbering given on the magazine itself. Ashley, Michael (1976). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 3 1946–1955. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. p. 87. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- del Rey, Lester (1979). The World of Science Fiction and Fantasy: The History of a Subculture. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 166–167. ISBN 0-345-25452-X.

- See the individual issues. An online index is available at "ISFDB: Fantastic Universe Science Fiction". Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Ashley, Michael (1978). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Part 4 1956–1965. London: New English Library. p. 28. ISBN 0-450-03438-0.

- See for example the statement of circulation in "Statement Required by the Act of October 23, 1962". Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact. LXXVI (4): 161. December 1965.

- "Bibliography: The Fantastic Universe Omnibus". Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Mentioned in the "Notable Fiction" section of Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc. pp. 560–561. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.

- Budrys and Brunner stories mentioned as notable in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter, eds. (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. p. 757. ISBN 0-312-09618-6. The other stories are frequently reprinted or represent prominent authors.

References

- Ashley, Michael (1976). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 3 1946–1955. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- Ashley, Michael (1978). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Part 4 1956–1965. London: New English Library. ISBN 0-450-03438-0.

- del Rey, Lester (1979). The World of Science Fiction and Fantasy: The History of a Subculture. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25452-X.

- Clute, John & Nicholls, Peter (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.