Independent school

An independent school is independent in its finances and governance. Also known as private schools, non-governmental, privately funded, or non-state schools,[1] they are not administered by local, state or national governments. In British English, an independent school usually refers to a school which is endowed, i.e. held by a trust, charity, or foundation, while a private school is one that is privately owned.[2]

Independent schools are usually not dependent upon national or local government to finance their financial endowment. They typically have a board of governors who are elected independently of government and have a system of governance that ensures their independent operation.

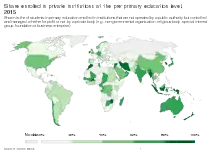

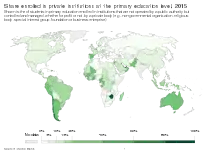

Children who attend such schools may be there because they (or their parents) are dissatisfied with government-funded schools (in UK state schools) in their area. They may be selected for their academic prowess, prowess in other fields, or sometimes their religious background. Private schools retain the right to select their students and are funded in whole or in part by charging their students for tuition, rather than relying on taxation through public (government) funding; at some private schools students may be eligible for a scholarship, lowering this tuition fee, dependent on a student's talents or abilities (e.g., sports scholarship, art scholarship, academic scholarship), need for financial aid, or tax credit scholarships[3] that might be available. Roughly one in 10 U.S. families have chosen to enroll their children in private school for the past century.[4]

Some private schools are associated with a particular religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, or Protestantism. Although independent schools may have a religious affiliation, the precise use of the term excludes parochial (and other) schools if there is a financial dependence upon, or governance subordinate to, outside organizations. These definitions generally apply equally to both primary and secondary education.

Types

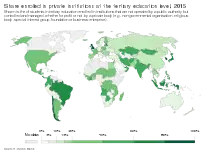

In the United Kingdom and several other Commonwealth countries including Australia and Canada, the use of the term is generally restricted to primary and secondary educational levels; it is almost never used of universities and other tertiary institutions.[5] Private education in North America covers the whole gamut of educational activity, ranging from pre-school to tertiary level institutions.[6] Annual tuition fees at K–12 schools range from nothing at so called 'tuition-free' schools to more than $45,000 at several New England preparatory schools.[7]

The secondary level includes schools offering years 7 through 12 (year twelve is known as lower sixth) and year 13 (upper sixth). This category includes university-preparatory schools or "prep schools", boarding schools, and day schools. Tuition at private secondary schools varies from school to school and depends on many factors, including the school's location, the willingness of parents to pay, peer tuitions, and the school's financial endowment.[8] High tuition, schools claim, is used to pay higher salaries for the best teachers and also used to provide enriched learning environments, including a low student-to-teacher ratio, small class sizes and services, such as libraries, science laboratories and computers. Some private schools are boarding schools, and many military academies are privately owned or operated as well.

Religiously affiliated and denominational schools form a subcategory of private schools. Some such schools teach religious education, together with the usual academic subjects, to impress their particular faith's beliefs and traditions in the students who attend. Others use the denomination as a general label to describe what the founders based their belief, while still maintaining a fine distinction between academics and religion. They include parochial schools,[9] a term which is often used to denote Roman Catholic schools. Other religious groups represented in the K–12 private education sector include Protestants, Jews, Muslims, and Orthodox Christians.

Many educational alternatives, such as independent schools, are privately financed.[10] Private schools often avoid some state regulations, although in the name of educational quality, most comply with regulations relating to the educational content of classes. Religious private schools often add religious instruction to the courses provided by local public schools.

Special assistance schools aim to improve the lives of their students by providing services tailored to the particular needs of individual students. Such schools include tutoring schools and schools to assist the learning of Disabled children.

By country

Australia

In Australia, independent schools, sometimes referred to as private schools, are a sub-set of non-government schools that, for administration purposes, are not operated by a government authority and have a system of governance that ensures its independent operation. Such schools are mostly operated by an independently elected school council or board of governors and range broadly in the type of school-education provided and the socio-economics of the school community served. Some independent schools are run by religious institutes; others have no religious affiliation and are driven by a national philosophy (such as international schools), pedogogical philosophy (such as Waldorf-Steiner schools), or specific needs (such as special schools).[11]

Independent and Catholic schools in Australia make up more than 34% of total enrolments.[11] Catholic schools, which usually have lower fees, make up a sizeable proportion of total enrolments (nearly 15%) and are usually regarded as a school sector of their own within the broad category of independent schools. Enrolments in non-government schools have been growing steadily at the expense of enrolments in government schools, which have seen their enrolment share reduce from 78.1 percent to 65 percent since 1970, although the rate of growth has slowed in the later years.[11]

Australian independent schools differ from those in the United States as the Australian Government provides funding to all schools including independent schools using a 'needs-based' funding model. This model was based on a Socio-Economic Status (SES) score, derived by selecting a sample of parents' addresses and mapping these to various household income and education data points collected from the national census conducted every five years. In 2013, after release of the (first) Gonski Report, the funding formula was changed to compute individual school funding compared to a School Resourcing Standard (SRS). The SRS uses exam results from the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) tests, calculates the SRS from a cohort of well-performing schools, and applies this formula to other schools on the assumption that they should be able to achieve similar results from similar funding. The funding provided to independent schools is on a sliding scale and still has a "capacity to pay" element; however, on average, funding granted to the independent school sector is 40 percent of that required to operate government schools, the remainder being made up by tuition fees and donations from parents. The majority of the funding comes from the Commonwealth Government, while the state and territory governments provide about one-third of the Commonwealth amount. The Turnbull Government commissioned Gonski in 2017 to chair the independent Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools, commonly called Gonski 2.0.[12] The government published the report on 30 April 2018.[13] Following negotiation, bilateral agreements between the Commonwealth of Australia with each state and territory commenced on 1 January 2019, with the exception of Victoria, whose bilateral agreement commenced on 1 February 2019. The funding agreements provide states with funding for government schools (20 percent) and non-government schools (80 percent) taking into consideration annual changes in enrolment numbers, indexation and student or school characteristics. A National School Resourcing Board was charged with the responsibility of independently reviewing each state's compliance with the funding agreement(s).[14]

Independent school fees can vary from under $100 per month[15] to $2,000 and upwards,[16][17] depending on the student's year level, the school's size, and the socioeconomics of the school community. In late 2018 it was reported that the most expensive independent schools (such as the APS Schools, the AGSV Schools in Melbourne, the GPS Schools, QGSSSA Schools in Brisbane and the NSW GPS Schools, Combined Associated Schools and the ISA Schools in Sydney and New South Wales) charge fees of up to $500,000 for the thirteen years of an independent school education.[18][19][20]

Private schools in Australia are always more expensive than their public counterparts[21]

There are two main categories of private schools in Australia: Catholic schools and Independent schools.[22]

Catholic schools

Catholic schools form the second-largest sector after government schools, with around 21% of secondary enrollments.[23] Most Australian Catholic schools belong to a system, like government schools, are typically co-educational and attempt to provide Catholic education evenly across the states. These schools are also known as "systemic". Systemic Catholic schools are funded mainly by state and federal government and have low fees.

Catholic schools, both systemic and independent, typically have a strong religious focus, and usually most of their staff and students are Catholic.[22]

Independent schools

Independent schools make up the last sector and are the most popular form of schooling for boarding students. Independent schools are non-government institutions that are generally not part of a system.

Although most are non-aligned, some of the best known independent schools also belong to the large, long-established religious foundations, such as the Anglican Church, Uniting Church and Presbyterian Church, but in most cases, they do not insist on their students' religious allegiance. These schools are typically viewed as "elite schools". Many of the "grammar schools" also fall in this category. They are usually expensive schools that tend to be up-market and traditional in style, some Catholic schools fall into this category as well, e.g. St Joseph's College, Gregory Terrace, Saint Ignatius' College, Riverview, St Gregory's College, Campbelltown, St Aloysius' College (Sydney) and St Joseph's College, Hunters Hill, as well as Loreto Kirribilli, Saint Scholastica's College, Monte Sant Angelo Mercy College and Loreto Normanhurst for girls.

Lower-fee independent schools exist and are often conducted by religious affiliations such as the Greek Orthodox church and other less prominent Christian denominations.

Canada

In Canada, independent school refers to elementary and secondary schools that follow provincial educational requirements but are not managed by the provincial ministry; the term independent is usually used to describe not-for-profit schools. In some provinces, independent schools are regulated by the Independent School Act and must offer a curriculum prescribed by the provincial government. Ontario has the most independent schools in Canada. These include Ridley College, Havergal College, Crescent School, St. Andrew's College, Columbia International College, The York School, Niagara Christian Collegiate and Ashbury College. Examples of independent schools in British Columbia are Brentwood College School, Little Flower Academy, Shawnigan Lake School, St. Margaret's School, and St. Michael's University School. In Quebec: Bishop's College School and Lower Canada College.

Many independent schools in Canada meet National Standards and are accredited by a national not-for-profit organization called Canadian Accredited Independent Schools (CAIS).

Independent schools in British Columbia are partially financed by municipal governments by Statutory and Permissive tax exemptions. The objective of the legislation appears to be to level the playing field between the private and public sector schools. These tax exemptions over a period of time result in considerable investment by municipal governments in the private school sector, yet legally they have no stake in the properties, as they remain in private hands. Depending on the financial structure of the school, parents may have a financial stake while their offspring are enrolled, but the investment is not continuous, and the enrollment deposit, which finances the school's capital expenditures, is returned upon leaving the school. The returned deposit is paid from the subsequent new enrolment, and it follows that no parent makes a long-term investment in the school. The municipal governments appear on balance to be the only long term investors, through the statutory and permissive tax exemptions, with no right to recapture these costs if the school is dissolved or any part of the assets is disposed of.

Robert Land Academy in Wellandport, Ontario is Canada's only independent military style school for boys in grades 6 through 12.

In 1999, 5.6% of Canadian students were enrolled in private schools,[24] some of which are religious or faith-based schools, including Christian, Catholic, Jewish, and Islamic schools. Some private schools in Canada are considered world class, especially some boarding schools with a long and illustrious history. Private schools have sometimes been controversial, with some[25] in the media and in Ontario's Provincial Ministry of Education asserting that students may buy inflated grades from private schools.[26]

Germany

The right to create private schools in Germany is in Article 7, Paragraph 4 of the Grundgesetz and cannot be suspended even in a state of emergency. It is also not possible to abolish these rights. This unusual protection of private schools was implemented to protect these schools from a second Gleichschaltung or similar event in the future. Still, they are less common than in many other countries. Overall, between 1992 and 2008 the percent of pupils in such schools in Germany increased from 6.1% to 7.8% (including rise from 0.5% to 6.1% in the former GDR). Percent of students in private high schools reached 11.1%.[27]

There are two types of private schools in Germany, Ersatzschulen (literally: substitute schools) and Ergänzungsschulen (literally: auxiliary schools). There are also private Hochschulen (private colleges and universities) in Germany, but similar to the UK, the term private school is almost never used of universities or other tertiary institutions.

Ersatzschulen are ordinary primary or secondary schools, which are run by private individuals, private organizations or religious groups. These schools offer the same types of diplomas as public schools. Ersatzschulen lack the freedom to operate completely outside government regulation. Teachers at Ersatzschulen must have at least the same education and at least the same wages as teachers at public schools, an Ersatzschule must have at least the same academic standards as a public school and Article 7, Paragraph 4 of the Grundgesetz, also forbids segregation of pupils according to the means of their parents (the so-called Sonderungsverbot). Therefore, most Ersatzschulen have very low tuition fees or offer scholarships, compared to most other Western European countries. However, it is not possible to finance these schools with such low tuition fees, which is why all German Ersatzschulen are additionally financed with public funds. The percentages of public money could reach 100% of the personnel expenditures. Nevertheless, Private Schools became insolvent in the past in Germany.

Ergänzungsschulen are secondary or post-secondary (non-tertiary) schools, which are run by private individuals, private organizations or rarely, religious groups and offer a type of education which is not available at public schools. Most of these schools are vocational schools. However, these vocational schools are not part of the German dual education system. Ergänzungsschulen have the freedom to operate outside government regulation and are funded in whole by charging their students tuition fees.

Italy

In Italy education is predominantly public; about one-fifth of schools are private, attended by about one out of 10 Italian schoolchildren. The Italian constitution states that education is to be public, free,[28] and compulsory for at least 8 years.

The majority of schools not administered by the state are Catholic. In the period 2008–2009 Catholic schools were about 57% of all private schools, with a tendency to decrease.

India

In India, private schools are called independent schools, but since some private schools receive financial aid from the government, it can be an aided or an unaided school. So, in a strict sense, a private school is an unaided independent school. For the purpose of this definition, only receipt of financial aid is considered, not land purchased from the government at a subsidized rate. It is within the power of both the union government and the state governments to govern schools since Education appears in the Concurrent list of legislative subjects in the constitution. The practice has been for the union government to provide the broad policy directions while the states create their own rules and regulations for the administration of the sector. Among other things, this has also resulted in 30 different Examination Boards or academic authorities that conduct examinations for school leaving certificates. Prominent Examination Boards that are present in multiple states are the CBSE and the CISCE, NENBSE

Legally, only non-profit trusts and societies can run schools in India. They will have to satisfy a number of infrastructure and human resource related criteria to get Recognition (a form of license) from the government. Critics of this system point out that this leads to corruption by school inspectors who check compliance and to fewer schools in a country that has the largest adult illiterate population in the world. While official data does not capture the real extent of private schooling in the country, various studies have reported unpopularity of government schools and an increasing number of private schools. The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), which evaluates learning levels in rural India, has been reporting poorer academic achievement in government schools than in private schools. A key difference between the government and private schools is that the medium of education in private schools is English while it is the local language in government schools.

Indonesia

Private schools can be found across Indonesia. All private schools in Indonesia are established by foundations. The costs of education are not subsidized by the government. The differences between private schools and public schools depend on each school. Each private school applies policies from the Indonesian Government, and all private schools give the opportunity of additional activities whether cultural or for sport. Lots of Private schools in Indonesia are also influenced by religions (Islam, Christian, Catholic, Hindu, Buddha). But there are also national private schools that are not influenced by religion but rather have a special program.

Ireland

In Ireland, the internationally recognised definition of "private school" is misleading and a more accurate distinction is between fee-charging schools and non-fee-charging schools. This is because approximately 85% of all schools are private schools (Irish: scoil phríobháideach) by virtue of not being owned by the state. The Roman Catholic Church is the largest owner of schools in Ireland, with other religious institutions owning the remaining private schools. Nevertheless, despite the vast majority of schools being under the ownership of private institutions, a large majority of all their costs, including teachers' salaries, are paid for by the Irish state. Of these private schools, only a very small minority actually charge fees. In 2007, 'The number of schools permitted to charge fees represents 7.6% of the 723 post primary level schools and they cater for 7.1% of the total enrolment.'[29] If a fee-charging school wishes to employ extra teachers they are paid for with school fees, which tend to be relatively low in Ireland compared to the rest of the world. Because state funding plays a fundamental role in the finances of all but one fee-charging school, they must undergo similar state inspection to non-fee-charging schools. This is due to the requirement that the state ensure that children receive a certain minimum education; Irish state subsidised fee-charging schools must still work towards the Junior Certificate and the Leaving Certificate, for example.

The single fee-charging secondary school in Ireland which receives no state funding, the Nord Anglia International School Dublin, does not have to undergo the state supervision which all the other fee-charging schools undergo. Students there also sit the International Baccalaureate rather than the Irish Leaving Certificate which every other Irish secondary school student sits. In exchange, however, Nord Anglia students pay some €25,000 per annum in fees, compared to c. €4,000 – €8,000 per annum fees by students in all other fee-charging Irish schools.[30] Many fee-charging schools in Ireland also double as boarding schools. The fees for these may then rise up to €25,000 per year. All the state-subsidised fee-charging schools are run by a religious order, e.g., the Society of Jesus or Congregation of Christian Brothers, etc. The major private schools being Blackrock College, Clongowes Wood College, Castleknock College, Belvedere College, Gonzaga College and Terenure College.

There are also a few fee-charging international schools in Ireland, including a French school, a Japanese school and a German school.

Lebanon

In Lebanon the vast majority of students attend private schools, most of which are owned and operated by the Maronite Church. Government owned schools do exist, but only a small percentage of the population attend these aging structures, most of which were built in the mid-twentieth century. Educational standards are very high in Lebanon, but only those who can afford them are found in these schools. This presents a massive issue as not only does it place a burden on parents and younger families, but it also prevents certain individuals from realizing their full potential.

Lebanon utilizes an unusual mixed system, with French, English and American systems intertwining, sometimes in the same facility. As of 2015, approximately 85% of Secondary and High School graduates continued on to university.

Malaysia

Chinese schools were being founded by the ethnic Chinese in Malaysia as early as the 19th century. The schools were set up with the main intention of providing education in the Chinese language. As such, their students remain largely Chinese to this day even though the school themselves are open to people of all races and backgrounds.

After Malaysia's independence in 1957, the government instructed all schools to surrender their properties and be assimilated into the National School system. This caused an uproar among the Chinese and a compromise was achieved in that the schools would instead become "National Type" schools. Under such a system, the government is only in charge of the school curriculum and teaching personnel while the lands still belonged to the schools. While Chinese primary schools were allowed to retain Chinese as the medium of instruction, Chinese secondary schools are required to change into English-medium schools. Over 60 schools converted to become National Type schools.

Nepal

In much of Nepal, the schooling offered by the state governments would technically come under the category of "public schools". They are federal- or state-funded, and have no or minimal fees.

The other category of schools are those run and partly or fully funded by private individuals, private organizations and religious groups. The ones that accept government funds are called 'aided' schools. The private 'un-aided' schools are fully funded by private parties. The standard and the quality of education is quite high. Technically, these would be categorized as private schools, but many of them have the name "Public School" appended to them (e.g., the Galaxy Public School in Kathmandu). Most of the middle-class families send their children to such schools, which might be in their own city or far off, like boarding schools. The medium of education is English, but as a compulsory subject, Nepali or the state's official language is also taught. Preschool education is mostly limited to organized neighbourhood nursery schools.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands over two-thirds of state-funded schools operate autonomously, with many of these schools being linked to faith groups.[31] The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, ranks the education in the Netherlands as the 9th best in the world as of 2008, being significantly higher than the OECD average.[32]

New Zealand

As of April 2014, there were 88 private schools in New Zealand, catering for around 28,000 students or 3.7% of the entire student population.[33] Private school numbers have been in decline since the mid-1970s as a result of many private schools opting to become state-integrated schools, mostly due of financial difficulties stemming from changes in student numbers or the economy. State-integrated schools keep their private school special character and receives state funds in return for having to operate like a state school, e.g. they must teach the state curriculum, they must employ registered teachers, and they can't charge tuition fees (they can charge "attendance dues" for the upkeep on the still-private school land and buildings). The largest decline in private school numbers occurred between 1979 and 1984, when the nation's then-private Catholic school system integrated. As a result, private schools in New Zealand are now largely restricted to the largest cities (Auckland, Hamilton, Wellington and Christchurch) and niche markets.

Private schools are almost fully funded by tuition fees paid by students' parents, but they do receive some government subsidies. Private schools are popular for academic and sporting performance, prestige, exclusivity and old boys/girls networks; however, many state-integrated schools and some prestigious single-sex state schools, such as Auckland Grammar School and Wellington College, are actively competitive with private schools in academic and sporting achievement, history and character.

Private schools are often Anglican, such as King's College and Diocesan School for Girls in Auckland, St Paul's Collegiate School in Hamilton, St Peter's School in Cambridge, Samuel Marsden Collegiate School in Wellington, and Christ's College and St Margaret's College in Christchurch; or Presbyterian, such as Saint Kentigern College and St Cuthbert's College in Auckland, Scots College and Queen Margaret College in Wellington, and St Andrew's College and Rangi Ruru Girls' School in Christchurch. However, the Catholic schismatic group, the Society of St Pius X in Wanganui operates three private schools (including the secondary school, St Dominic's College).

A recent group of private schools run as a business has been formed by Academic Colleges Group; with schools throughout Auckland, including ACG Senior College in Auckland's CBD, ACG Parnell College in Parnell, and international school ACG New Zealand International College.

Oman

Oman retains a number of independent private coeducational day schools of international renown and a majority of which are private educational grammar establishments offering Classics beyond Latin and Greek to include the ancient literary studies of Sanskrit, Hebrew and Arabic. Notable ones include the American British Academy, the British School Muscat, the Pakistan School Muscat, the Indian School Al Ghubra and The Sultan's School.

Philippines

In the Philippines, the private sector has been a major provider of educational services, accounting for about 7.5% of primary enrolment, 32% of secondary enrolment and about 80% of tertiary enrolment. Government regulations have given private education more flexibility and autonomy in recent years, notably by lifting the moratorium on applications for new courses, new schools and conversions, by liberalizing tuition fee policy for private schools, by replacing values education for third and fourth years with English, mathematics and natural science at the option of the school, and by issuing the revised Manual of Regulations for Private Schools in August 1992.

The Education Service Contracting scheme of the government provides financial assistance for tuition and other school fees of students turned away from public high schools because of enrolment overflows. The Tuition Fee Supplement is geared to students enrolled in priority courses in post-secondary and non-degree programmes, including vocational and technical courses. The Private Education Student Financial Assistance is made available to underprivileged, but deserving high school graduates, who wish to pursue college/technical education in private colleges and universities.

In the school year 2001/02, there were 4,529 private elementary schools (out of a total of 40,763) and 3,261 private secondary schools (out of a total of 7,683). In 2002/03, there were 1,297 private higher education institutions (out of a total of 1,470).

Portugal

In Portugal, private schools were traditionally set up by foreign expatriates and diplomats in order to cater for their educational needs. Portuguese-speaking private schools are widespread across Portugal's main cities. International private schools are mainly concentrated in and around Lisbon, Porto, Braga, Coimbra and Covilhã, across the Portuguese region of Algarve, and in the autonomous region of Madeira. The Ministério da Educação acts as the supervisory and regulatory body for all schools, including international schools.

Singapore

In Singapore, after Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE), students can choose to enter a private high school. ("Private Schools." Private Schools in Singapore | Private Education, www.actualyse.com/prv/private-schools.aspx?c=SG&alang=en.)

South Africa

Some of the oldest schools in South Africa are private church schools that were established by missionaries in the early nineteenth century. The private sector has grown ever since. After the abolition of apartheid, the laws governing private education in South Africa changed significantly. The South African Schools Act of 1996[34] recognizes two categories of schools: "public" (state-controlled) and "independent" (which includes traditional private schools and schools which are privately governed).

In the final years of the apartheid era, parents at white government schools were given the option to convert to a "semi-private" form called Model C, and many of these schools changed their admissions policies to accept children classified to be of other races. Following the end of apartheid government, the legal form of "Model C" was abolished, however, the term continues to be used to describe government schools formerly reserved for white children.[35] These schools tend to produce better academic results than government schools formerly reserved for other "race groups".[36] Former "Model C" schools are state-controlled, not private. All schools in South Africa (including both independent and public schools) have the right to set compulsory school fees, and formerly model C schools tend to set much higher school fees than other public schools.

Sweden

In Sweden, pupils are free to choose a private school and the private school gets paid the same amount as municipal schools. Over 10% of Swedish pupils were enrolled in private schools in 2008. Sweden is internationally known for this innovative school voucher model that provides Swedish pupils with the opportunity to choose the school they prefer.[37][38][39][40][41] For instance, the biggest school chain, Kunskapsskolan ("The Knowledge School"), offers 30 schools and a web-based environment, has 700 employees and teaches nearly 10,000 pupils.[37]

United Kingdom

Non-governmental schools generally prefer to be called independent schools, because of their freedom to operate outside government and local government control.[42] Elite institutions for older pupils, which charge high fees, are typically described as public schools. Preparatory schools in England and Wales prepare pupils up to 13 years old to enter public schools. In Scotland, where the education system has always been separate from the rest of Great Britain, the term 'public school' was used historically to refer to state schools for the general public.

According to The Good Schools Guide about 9% of children being educated in the United Kingdom are at fee-charging schools at GCSE level and 13% at A-level. Some independent schools are single-sex, although this is becoming less common.[43] As of 2011 fees range from under £3,000 to £21,000 and above per year for day pupils, rising to over £27,000 per year for boarders.[44] Costs differ in Scotland.[45]

On 15 August 2010 The Observer reported that the gap in A-Level achievement between independent schools and state schools in the UK was set to widen, with three times as many independently educated students achieving the new grade A*. The paper also noted that according to the "fair access watchdog" bright students from the poorest backgrounds were seven times less likely to go to a top university than their richer peers.[46]

However, one in four independently educated children come from postcodes with the national average income or below, and one in three receives assistance with school fees.[47] However, pupils' actual family incomes, which may be below or above the average for a particular postcode area, were not determined.

Evidence from a major longitudinal study suggests that British independent schools provide advantages in educational attainment and access to top universities,[48] and that graduates of such schools have a labour market advantage, even controlling for their educational qualifications.[49]

In the United Kingdom, independent education (or private education) has grown continually for the past twenty years.

England and Wales

In England and Wales, the more prestigious independent schools are known as 'public schools', sometimes subdivided into major and minor public schools. A modern definition of a public school refers to membership of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference, and this includes many independent grammar schools. The term 'public school' originally meant that the school was open to the public (as opposed to private tutors or the school being in private ownership).

Scotland

In Scotland,[50] schools not state-funded are known as independent or private schools. Independent schools may also be specialist or special schools – such as some music schools, Steiner Waldorf Education schools, or special education schools.[51]

Scottish independent schools currently educate over 31,000 students and employ approximately 3,500 teachers.[52] Schools are represented by the Scottish Council of Independent Schools (SCIS). All schools are still inspected by the state inspectorate, Education Scotland, and the Care Inspectorate. Independent schools in Scotland that are charities are subject to a specific test from the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, designed to demonstrate the public benefit[53] the schools provide.

United States

In the United States, the term "private school" can be correctly applied to any school for which the facilities and funding are not provided by the federal, state or local government; as opposed to a "public school", which is operated by the government or in the case of "charter schools", independently with government funding and regulation. The majority of private schools in the United States are operated by religious institutions and organizations.[54]

Independent schools in the United States educate a tiny fraction of the school-age population (slightly over 1% of the entire school-age population, around 10% of students who go to private schools). The essential distinction between independent schools and other private schools is self-governance and financial independence, i.e., independent schools own, govern, and finance themselves. In contrast, public schools are funded and governed by local and state governments, and most parochial schools are owned, governed, and financed by religious institutions such as a diocese or parish. Independent schools may be affiliated with a particular religion or denomination; however, unlike parochial schools, independent schools are self-owned and governed by independent boards of trustees. While independent schools are not subject to significant government oversight or regulation, they are accredited by the same six regional accreditation agencies that accredit public schools. The National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) is a membership organization of American pre-college independent schools.

The NAIS provides this definition of an Independent School:[55]

Independent schools are 501(c)3 nonprofit corporate entities, independent in governance and finance, meaning:

- Independent schools "own themselves" (as opposed to public schools owned by the government or parochial schools owned by the church) and govern themselves, typically with a self-perpetuating board of trustees that performs fiduciary duties of oversight and strategic duties of funding and setting the direction and vision of the enterprise, and by delegating day to day operations entirely to the head of school.

- Independent schools finance themselves (as opposed to public schools funded through the government and parochial schools subsidized by the church), largely through charging tuition, fund raising, and income from endowment.

Independence is the unique characteristic of this segment of the education industry, offering schools four freedoms that contribute to their success: the freedom to define their own unique missions; the freedom to admit and keep only those students well-matched to the mission; the freedom to define the qualifications for high quality teachers; and the freedom to determine on their own what to teach and how to assess student achievement and progress.

In the United States, there are more independent colleges and universities than public universities, although public universities enroll more total students. The membership organization for independent tertiary education institutions is the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities.[56]

Private schools are generally exempt from most educational regulations at the Federal level but are highly regulated at the state level.[57] These typically require them to follow the spirit of regulations concerning the content of courses in an attempt to provide a level of education equal to or better than that available in public schools.

In the nineteenth century, as a response to the perceived domination of the public school systems by Protestant political and religious ideas, many Roman Catholic parish churches, dioceses and religious orders established schools, which operate entirely without government funding. For many years, the vast majority of private schools in the United States were Catholic schools.[58]

A similar perception (possibly relating to the evolution vs. creationism debates) emerged in the late twentieth century among Protestants, which has resulted in the widespread establishment of new, private schools.

In many parts of the United States, after the 1954 decision in the landmark court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that demanded United States schools desegregate "with all deliberate speed", local families organized a wave of private "Christian academies". In much of the U.S. South, many white students migrated to the academies, while public schools became in turn more heavily concentrated with African-American students (see List of private schools in Mississippi). The academic content of the academies was usually College Preparatory. Since the 1970s, many of these "segregation academies" have shut down, although some continue to operate.

Funding for private schools is generally provided through student tuition, endowments, scholarship/school voucher funds, and donations and grants from religious organizations or private individuals. Government funding for religious schools is either subject to restrictions or possibly forbidden, according to the courts' interpretation of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment or individual state Blaine Amendments. Non-religious private schools theoretically could qualify for such funding without hassle, preferring the advantages of independent control of their student admissions and course content instead of the public funding they could get with charter status.

A similar concept, recently emerging from within the public school system, is the concept of "charter schools", which are technically independent public schools, but in many respects operate similarly to non-religious private schools.

Private schooling in the United States has been debated by educators, lawmakers and parents, since the beginnings of compulsory education in Massachusetts in 1852. The Supreme Court precedent appears to favor educational choice, so long as states may set standards for educational accomplishment. Some of the most relevant Supreme Court case law on this is as follows: Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976); Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972); Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925); Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923).

There is a potential conflict between the values espoused in the above cited cases and the limitations set forward in Article 29 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which is below described.[59]

As of 2012, quality private schools in the United States charged substantial tuition, close to $40,000 annually for day schools in New York City, and nearly $50,000 for boarding schools. However, tuition did not cover operating expenses, particularly at boarding schools. The leading schools such as the Groton School had substantial endowments running to hundreds of millions of dollars supplemented by fundraising drives. Boarding schools with a reputation for quality in the United States have a student body drawn from throughout the country, indeed the globe, and a list of applicants which far exceeds their capacity.[60]

See also

- Alternative school

- Convention against Discrimination in Education

- Freedom of education

- List of Friends schools

- Independent school (UK)

- Lutheran school

- Public school (UK)

- Right to Education

- State school

- Voucher

References

- Zaidi, Mosharraf. " Mosharraf Zaidi: Why we wanted to believe what Greg Mortenson was selling Archived 2012-07-09 at archive.today." National Post. 20 April 2011. Retrieved on 20 April 2011.

- Cheng, Haojing (1999). "Quality education and social stratification: The paradox of private schooling in China" (PDF). Current Issues in Comparative Education. 1 (2): 48–56 – via Delany.

- "What is a Tax-Credit Scholarship? – EdChoice". EdChoice. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Who Goes to Private School? Long-term enrollment trends by family income – Education Next". Education Next. 17 July 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Gibb, Nick (22 February 2018). "Commonwealth countries must ensure that each child has 12 years of quality education". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ourkids.net. "Private Schools Versus Public Schools | Private Vs Public". www.ourkids.net. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- "The 50 Most Expensive Boarding Schools In America". BusinessInsider.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Private School Endowments". The Houston School Survey – School Research, Reviews, & Forum. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "For most Americans, parochial school education outshines public schools". Crux. 25 August 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Alternative Schools: Education Outside The Traditional System". learninglab. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- Independent Schools Overview, Independent Schools Council of Australia, 2019, archived from the original on 11 August 2019, retrieved 27 August 2019

- "What is Gonski 2.0?". isca.edu.au. Independent Schools Council of Australia. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Education Excellence in Australian Schools" (PDF), Department of Education and Training, Australian Government, 30 April 2018, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2018, retrieved 30 April 2018

- "How Are Schools Funded in Australia?". Department of Education. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "School Fees", Good Schools Guide, Good Education Group, retrieved 6 April 2019

- Speranza, Laura (29 May 2011). "$500,000 a child: How much private schooling costs parents". The Sunday Telegraph. Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Private School Fees and Costs, Exfin International Pty LTD., retrieved 7 June 2016

- Singhal, Pallavi; Keoghan, Sarah (26 December 2018). "Sydney private school fees hit $38,000 for the first time". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Kinniburgh, Chanel (30 January 2019). "Estimated total cost of a government, Catholic and independent education revealed". news.com.au. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Bolton, Robert (29 January 2019). "'Mind blowing': Top private school education nears $500,000". Financial Review. Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Evershed, Nick (11 March 2014). "Datablog: private schools are winning over Australian parents". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- The National Education Directory Australia: Private Schools in Australia Archived 21 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine (accessed:07-08-2007)

- "Private Schools". australian-children. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Trends in the use of private education". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Chubb, J. (2015). "The Private School Stigma." The Atlantic.

- Burgmann, Tamsyn (10 August 2009). "'Buying a credit' trend worrying for educators". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Clara Weiss. (5 July 2011). "Private schools boom in Germany". World Socialist Web Site. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- LL.M., Prof. Dr. Axel Tschentscher. "ICL – Italy – Constitution". www.servat.unibe.ch. Archived from the original on 20 May 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Policy and Education Reports" (PDF). www.gov.ie.

- "Our Fees - 2019/20 | Nord Anglia International School Dublin". www.nordangliaeducation.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019.

- Coughlan, Sean (11 February 2003). "State-funded self-rule in Dutch schools". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Directory of Schools – as of 1 April 2014". New Zealand Ministry of Education. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- "South African Schools Act (No. 84 of 1996)". Polity.org.za. Archived from the original on 9 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Hayes, Steve (28 February 2012). "Notes from underground: Twenty years of Model C". Methodius.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "Institute of Race Relations (IRR) — Institute of Race Relations". Sairr.org.za. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "Making money from schools: The Swedish model". The Economist. 12 June 2008. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- "Made in Sweden: the new Tory education revolution". The Spectator. 2008. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009.

- Baker, Mike (5 October 2004). "Swedish parents enjoy school choice". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- "Embracing private schools: Sweden lets companies use taxes for cost-efficient alternatives". Washington Times. 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- Munkhammar, Johnny (25 May 2007). "How choice has transformed education in Sweden". London: The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Green, Francis; Kynaston, David (2019). Engines of privilege : Britain's private school problem. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-5266-0127-8. OCLC 1108696740.

- "ISC Annual Census 2007". Isc.co.uk. 4 May 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "Help and advice on finding the right school for your child". The Good Schools Guide. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "Meeting the Cost". SCIS. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Vasagar, Jeevan (15 August 2010). "A-level results: Public schools expected to take lion's share of new A* grades". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "ISC Social Diversity Study". Isc.co.uk. 1 March 2006. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- Sullivan, A., Parsons, S., Wiggins, R., Heath, A., & Green, F. (2014). Social origins, school type and higher education destinations. Oxford Review of Education, 40(6), 739–763.

- Sullivan, A., Parsons, S., Green, F., Wiggins, R. D., & Ploubidis, G. (2017). The path from social origins to top jobs: social reproduction via education. The British journal of sociology.

- "Home". SCIS. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- "Special needs schools". Archived from the original on 3 May 2009.

- "Facts and Statistics: Pupil numbers". Scottish Council of Independent Schools. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Public Benefit » SCIS". scis.org.uk.

- "Number of private schools, by religious orientation and community type: 1989–90 through 2005–06". Nces.ed.gov. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- How do you define independent school? What is the definition of independent school? Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "About NAICU". Naicu.edu. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- "State Regulations of Private Schools" (PDF). US Department of Education. US Department of Education. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "CAPE | Private School Facts". www.capenet.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Witham, Joan. (1997). "Public or private schools? A dilemma for gifted students?" Roeper Review, 19, pp. 137–141.

- R. Scott Asen (23 August 2012). "Is Private School Not Expensive Enough?" (Op-ed by informed person). New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

Further reading

- Hein, David (4 January 2004). "What Has Happened to Episcopal Schools?" The Living Church, 228, no. 1, 21–22.

- Porter Sargent Staff, The Handbook of Private Schools: An Annual Descriptive Survey of Independent Education Archived 6 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine 1914–. Porter Sargent Handbooks, Boston. ISSN 0072-9884.