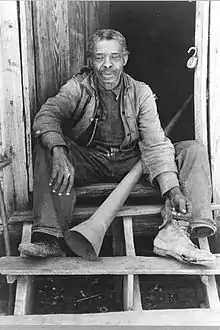

Freedman

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self-purchase. A fugitive slave is a person who escaped enslavement by fleeing.

Ancient Rome

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become plebeian citizens.[1] The act of freeing a slave was called manumissio, from manus, "hand" (in the sense of holding or possessing something), and missio, the act of releasing. After manumission, a slave who had belonged to a Roman citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.[2] A slave who had acquired libertas was known as a libertus ("freed person", feminine liberta) in relation to his former master, who was called his or her patron (patronus).

As a social class, freed slaves were liberti, though later Latin texts used the terms libertus and libertini interchangeably.[3] Libertini were not entitled to hold public office or state priesthoods, nor could they achieve legitimate senatorial rank. During the early Empire, however, freedmen held key positions in the government bureaucracy, so much so that Hadrian limited their participation by law.[4] Any future children of a freedman would be born free, with full rights of citizenship.

The Claudian Civil Service set a precedent whereby freedmen could be used as civil servants in the Roman bureaucracy. In addition, Claudius passed legislation concerning slaves, including a law stating that sick slaves abandoned by their owners became freedmen if they recovered. The emperor was criticized for using freedmen in the Imperial Courts.

Some freedmen enjoyed enormous success and became quite wealthy. The brothers who owned House of the Vettii, one of the biggest and most magnificent houses in Pompeii, are thought to have been freedmen. A freedman who became rich and influential might still be looked down on by the traditional aristocracy as a vulgar nouveau riche. Trimalchio, a character in the Satyricon of Petronius, is a caricature of such a freedman.

Arabian and North African slavery

For centuries, Arab slave traders took and transported an estimated 10 to 15 million sub-Saharan Africans to slavery in North Africa and the Middle East. They also enslaved Europeans (known as Saqaliba) from coastal areas and the Balkans. The slaves were predominantly women. Many Arabs took women slaves as concubines in their harems. In the patrilineal Arab societies, the mixed-race children of concubines and Arab men were considered free. They were given inheritance rights related to their fathers' property. No studies have been done of the influence of African-Arab descendants in the societies.

United States

In the United States, the terms "freedmen" and "freedwomen" refer chiefly to former slaves emancipated during and after the American Civil War by the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment. Slaves freed before the war (usually by individual manumissions, often in wills) were generally referred to as "Free Negroes" or free blacks. In addition, there was a population of black Americans born free.

The great majority of families of free people of color recorded in the US census in the Upper South in the first two decades after the Revolutionary War have been found to have descended from unions between white women (indentured servants or free) and black men (whether indentured servants, slave or free) in colonial Virginia. According to the legal principle of partus sequitur ventrem, in the slave colonies (later states) children were born into the social status of their mothers; thus, mixed-race children of white women were born free.[5] Such free families of color tended to migrate to the frontier of Virginia and other Upper South colonies, and then west into Kentucky, the future West Virginia, and Tennessee.[5] In addition, during the first two decades after the Revolution, slaveholders freed thousands of slaves in the Upper South, inspired by revolutionary ideals. Most Northern states abolished slavery, some on a gradual basis.

In Louisiana and other areas of the former New France, free people of color were classified in French as gens de couleur libres. They were generally born to black or mixed-race mothers and white fathers of ethnic French or other European ancestry. The fathers sometimes freed their children and sexual partners, leading to the growth of the community of Creoles of color, or free people of color. New Orleans had the largest community of free people of color, well-established before the US acquired Louisiana. The French and Spanish colonial rulers had given the free people of color more rights than most free blacks had in the American South.

In addition, there were sizable communities of free people of color in French Caribbean colonies, such as Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) and Guadeloupe. Due to the violence of the Haitian Revolution, many free people of color, who were originally part of the revolution, fled the island as refugees after being attacked by slave rebels, particularly in the north of the island. Some went first to Cuba, from where they immigrated to New Orleans in 1808 and 1809 after being expelled when Napoleon invaded Spanish territory in Europe. Many brought slaves with them. Their numbers strengthened the French-speaking community of enslaved black peoples, as well as the free people of color. Other refugees from Saint-Domingue settled in Charleston, Savannah, and New York.

Emancipation

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 declared all enslaved persons in the Confederacy—states in rebellion and not under the control of the Union—to be permanently free. It did not end slavery in the five border states that had stayed in the Union. Slavery elsewhere was abolished by state action, or with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in December of 1865. The Civil Rights Act of 1866, passed over the veto of President Andrew Johnson, gave the formerly enslaved full citizenship (except for voting) in the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment was passed to make clear that Congress had the legal authority to do so. The Fifteenth Amendment gave voting rights to all adult males; only adult males had the franchise among whites. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments are known as the "civil rights amendments", the "post-Civil War amendments", and the "Reconstruction Amendments".

To help freedmen transition from slavery to freedom, including a free labor market, President Abraham Lincoln created the Freedmen's Bureau, which assigned agents throughout the former Confederate states. The Bureau also founded schools to educate freedmen, both adults and children; helped freedmen negotiate labor contracts; and tried to minimize violence against freedmen. The era of Reconstruction was an attempt to establish new governments in the former Confederacy and to bring freedmen into society as voting citizens. Northern church bodies, such as the American Missionary Association and the Freewill Baptists, sent teachers to the South to assist in educating freedmen and their children, and eventually established several colleges for higher education. U.S. Army occupation soldiers were stationed throughout the South via military districts enacted by the Reconstruction Acts; they protected freedmen in voting polls and public facilities from violence and intimidation by white Southerners, which were common throughout the region.

Native American Freedmen

The Cherokee, Choctaw and Creek nations were among those Native American tribes that held enslaved blacks before and during the American Civil War.[6] They supported the Confederacy during the war, supplying some warriors in the West, as they were promised their own state if the Confederacy won. After the end of the war, the U.S. required these tribes to make new peace treaties, and to emancipate their slaves. They were required to offer full citizenship in their tribes to those freedmen who wanted to stay with the tribes. Numerous families had intermarried by that time or had other personal ties. If freedmen left the tribes, they would become US citizens.

Cherokee Freedmen

In the late 20th century, the Cherokee Nation voted for restrictions on membership to only those descendants of people listed as "Cherokee by blood" on the Dawes Rolls of the early 20th century, a decision that excluded most Cherokee Freedmen (by that time this term referred to descendants of the original group). In addition to arguing that the post-Civil War treaties gave them citizenship, the Freedmen have argued that the Dawes Rolls were often inaccurate, recording as freedmen even those individuals who had partial Cherokee ancestry and were considered Cherokee by blood. The Choctaw Freedmen and Creek Freedmen have similarly struggled with their respective tribes over the terms of citizenship in contemporary times. (The tribes have wanted to limit those who can benefit from tribal citizenship, in an era in which gaming casinos are yielding considerable revenues for members.) The majority of members of the tribes have voted to limit membership, and as sovereign nations, they have the right to determine their rules. Descendants of freedmen believe their long standing as citizens since the post-Civil War treaties should be continued. In 2017 the Cherokee Freedmen were granted citizenship again in the tribe.[7][8][9]

See also

- Black Seminoles

- Choctaw freedmen

- Creek Freedmen

- Freedman's Hospital

- Freedmen's Aid Society

- Freedmen's Bureau

- Freedmen's Bureau bills

- Freedmen's Colony of Roanoke Island

- Freedman's Savings Bank

- Freedmen's town

References

- "Slaves & Freemen". PBS.

- Millar, Fergus (1998–2002). The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. University of Michigan. pp. 23 & 209.

- Mouritsen, Henrik (2011). The Freedman in the Roman World. Cambridge University Press. p. 36.

- Berger, Adolf (1953). libertinus, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law. American Philological Society. p. 564.

- Heinegg, Paul (1995–2005). Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware.

- Walker, Mark; Cameron, Chris (October 8, 2021). "After Denying Care to Black Natives, Indian Health Service Reverses Policy". The New York Times.

- "Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash, et al. and Marilyn Vann, et al. and Ryan Zinke, Secretary of the Interior ruling, August 30, 2017".

- "Judge Rules That Cherokee Freedmen Have Right To Tribal Citizenship". npr. 2017-08-31. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- "Cherokee Nation Attorney General Todd Hembree issues statement on Freedmen ruling, August 31, 2017 (Accessible in PDF format as of September 8, 2017" (PDF).