Gelatin dessert

Gelatin desserts (also Jelly, Jello, Jinkington, or Jinkies) are desserts made with a sweetened and flavoured processed collagen product (gelatin). This kind of dessert was first recorded as jelly by Hannah Glasse in her 18th-century book The Art of Cookery, appearing in a layer of trifle. Jelly is also featured in the best selling cookbooks of English food writers Eliza Acton and Isabella Beeton in the 19th century.

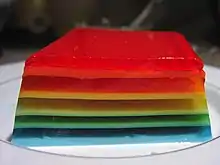

A multicoloured layered gelatin-based dessert | |

| Type | Dessert |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Serving temperature | Chilled |

| Main ingredients | Gelatin |

They can be made by combining plain gelatin with other ingredients or by using a premixed blend of gelatin with additives. Fully prepared gelatin desserts are sold in a variety of forms, ranging from large decorative shapes to individual serving cups.

Popular brands of premixed gelatin include: Aeroplane Jelly in Australia, Hartley's (formerly Rowntree's) in the United Kingdom, and Jell-O from Kraft Foods and Royal from Jel Sert in North America. In the US and Canada this dessert is known by the genericized trademark "jello".

History

Before gelatin became widely available as a commercial product, the most typical gelatin dessert was "calf's foot jelly". As the name indicates, this was made by extracting and purifying gelatin from the foot of a calf. This gelatin was used for savory dishes in aspic, or was mixed with fruit juice and sugar for a dessert.[1]

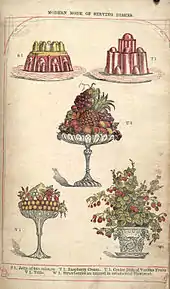

In the eighteenth century, gelatin from calf's feet, isinglass and hartshorn was colored blue with violet juice, yellow with saffron, red with cochineal and green with spinach and allowed to set in layers in small, narrow glasses. It was flavored with sugar, lemon juice and mixed spices. This preparation was called jelly; English cookery writer Hannah Glasse was the first to record the use of this jelly in trifle in her book The Art of Cookery, first published in 1747.[2] Preparations on making jelly (including illustrations) appear in the best selling cookbooks of English writers Eliza Acton and Isabella Beeton in the 19th century.

Due to the time consuming nature of extracting gelatin from animal bones, gelatin desserts were a status symbol up until the mid-19th century as it indicated a large kitchen staff.[3] Jelly molds were very common in the batteries de cuisine of stately homes.[4]

_(14577292709).jpg.webp)

Preparation

To make a gelatin dessert, gelatin is dissolved in hot liquid with the desired flavors and other additives. These latter ingredients usually include sugar, fruit juice, or sugar substitutes; they may be added and varied during preparation, or pre-mixed with the gelatin in a commercial product which mainly requires the addition of hot water.

In addition to sweeteners, the prepared commercial blends generally contain flavoring agents and other additives, such as adipic acid, fumaric acid, sodium citrate, and artificial flavorings and food colors. Because the collagen is processed extensively, the final product is not categorized as a meat or animal product by the US federal government.

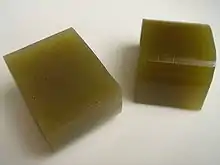

Prepared commercial blends may be sold as a powder or as a concentrated gelatinous block, divided into small squares. Either type is mixed with sufficient hot water to completely dissolve it, and then mixed with enough cold water to make the volume of liquid specified on the packet.

The solubility of powdered gelatin can be enhanced by sprinkling it into the liquid several minutes before heating, "blooming" the individual granules.[5] The fully dissolved mixture is then refrigerated, slowly forming a colloidal gel as it cools.

Gelatin desserts may be enhanced in many ways, such as using decorative molds, creating multicolored layers by adding a new layer of slightly cooled liquid over the previously-solidified one, or suspending non-soluble edible elements such as marshmallows or fruit. Some types of fresh fruit and their unprocessed juices are incompatible with gelatin desserts; see the Chemistry section below.

When fully chilled, the most common ratios of gelatin to liquid (as instructed on commercial packaging) usually result in a custard-like texture which can retain detailed shapes when cold but melts back to a viscous liquid when warm. A recipe calling for the addition of additional gelatin to regular jelly gives a rubbery product that can be cut into shapes with cookie cutters and eaten with fingers (called "Knox Blox" by the Knox company, makers of unflavored gelatin). Higher gelatin ratios can be used to increase the stability of the gel, culminating in gummy candies which remain rubbery solids at room temperature (see Bloom (test)).

The bloom strength of a gelatin mixture is the measure of how strong it is. It is defined by the force in grams required to press a 12.5 mm (0.49 in) diameter plunger 4 mm (0.16 in) into 112 g (4.0 oz) of a standard 6.67% w/v gelatin gel at 10 °C (50 °F). The bloom strength of a gel is useful to know when determining the possibility of substituting a gelatin of one bloom strength for a gelatin of another. One can use the following equation:

C x B½ = k

or C1(B1)½÷(B2)½ = C2

Where C = concentration, B = bloom strength and k = constant. For example, when making gummies, it is important to know that a 250 bloom gelatin has a much shorter (more thick) texture than a 180 bloom gelatin.[6]

Gelatin shots

A gelatin shot (usually called a Jell-O shot in North America and vodka jelly or jelly shot in the UK and Australia) is a shooter in which one or more liquors, usually vodka, rum, tequila, or neutral grain spirit, replaces some of the water or fruit juice that is used to congeal the gel.

The American satirist and mathematician Tom Lehrer claims to have invented the gelatin shot in the 1950s while working for the National Security Agency, where he developed vodka gelatin as a way to circumvent a restriction of alcoholic beverages on base.[7] An early published recipe for an alcoholic gelatin drink dates from 1862, found in How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon Vivant's Companion by Jerry Thomas: his recipe for "Punch Jelly" calls for the addition of isinglass or other gelatin to a punch made from cognac, rum, and lemon juice.[8][9]

Gelatin art desserts

Gelatin art desserts, also known as 3D gelatin desserts, are made by injecting colorful shapes into a flavored gelatin base. This 3D gelation art technique originated from Mexico and has spread along to Western and Pacific countries.

These desserts are made using high quality gelatin that has a high bloom value and low odor and taste. The clear gelatin base is prepared using gelatin, water, sugar, citric acid and food flavoring.

When the clear gelatin base sets, colorful shapes are injected using a syringe.

The injected material usually consists of a sweetener (most commonly sugar), some type of edible liquid (milk, cream, water, etc.), food coloring and a thickening agent such as starch or additional gelatin.

The shapes are drawn by making incisions in the clear gelatin base using sharp objects. Colored liquid is then allowed to fill the crevice and make the cut shape visible.

Most commonly, the shapes are drawn using sterile medical needles or specialized precut gelatin art tools that allow the shape to be cut and filled with color at the same time.

Gelatin art tools are attached to a syringe and used to inject a predetermined shape into gelatin.

When combined with other ingredients, such as whipping cream or mousse, gelatin art desserts can be assembled into visually impressive formations resembling a cake.

Gelatin substitutes

Other culinary gelling agents can be used instead of animal-derived gelatin. These plant-derived substances are more similar to pectin and other gelling plant carbohydrates than to gelatin proteins; their physical properties are slightly different, creating different constraints for the preparation and storage conditions. These other gelling agents may also be preferred for certain traditional cuisines or dietary restrictions.

Agar, a product made from red algae,[10] is the traditional gelling agent in many Asian desserts. Agar is a popular gelatin substitute in quick jelly powder mix and prepared dessert gels that can be stored at room temperature. Compared to gelatin, agar preparations require a higher dissolving temperature, but the resulting gels congeal more quickly and remain solid at higher temperatures, 40 °C (104 °F),[11] as opposed to 15 °C (59 °F)[12] for gelatin. Vegans and vegetarians can use agar to replace animal-derived gelatin.

Another common seaweed-based gelatin substitute is carrageenan, which has been used as a food additive since ancient times. It was first industrially-produced in the Philippines, which pioneered the cultivation of tropical red seaweed species (primarily Eucheuma and Kappaphycus spp.) from where carrageenan is extracted. The Philippines produces 80% of the world's carrageenan supply.[13] Carrageenan gelatin substitute are traditionally known as gulaman in the Philippines. It is widely used in various traditional desserts and are sold as dried bars or in powder form.[14][15] Unlike gelatin, gulaman sets at room temperature and is uniquely thermo-reversible. If melted at higher temperatures, it can revert to its original shape once cooled down.[16] Carrageenan jelly also sets more firmly than agar and lacks agar's occasionally unpleasant smell during cooking. The use of carrageenan as a gelatin substitute has spread to other parts of the world, particularly in cuisines with dietary restrictions against gelatin, like kosher and halal cooking. It has also been used in prepackaged Jello shots to make them shelf stable at room temperatures.

Konjac is a gelling agent used in many Asian foods, including the popular konnyaku fruit jelly candies.

Chemistry

Gelatin consists of partially hydrolyzed collagen, a protein which is highly abundant in animal tissues such as bone and skin. Collagen is a protein made up of three strands of polypeptide chains that form in a helical structure. To make a gelatin dessert, such as Jello, the collagen is mixed with water and heated, disrupting the bonds that hold the three strands of polypeptides together. As the gelatin cools, these bonds try to reform in the same structure as before, but now with small bubbles of liquid in between. This gives gelatin its semisolid, gel-like texture.[17]

Because gelatin is a protein that contains both acid and base amino groups, it acts as an amphoteric molecule, displaying both acidic and basic properties. This allows it to react with different compounds, such as sugars and other food additives. These interactions give gelatin a versatile nature in the roles that it plays in different foods. It can stabilize foams in foods such as marshmallows, it can help maintain small ice crystals in ice cream, and it can even serve as an emulsifier for foods like toffee and margarine.[6]

Although many gelatin desserts incorporate fruit, some fresh fruits contain proteolytic enzymes; these enzymes cut the gelatin molecule into peptides (protein fragments) too small to form a firm gel. The use of such fresh fruits in a gelatin recipe results in a dessert that never "sets".

Specifically, pineapple contains the protease (protein cutting enzyme) bromelain, kiwifruit contains actinidin, figs contain ficain, and papaya contains papain. Cooking or canning denatures and deactivates the proteases, so canned pineapple, for example, works fine in a gelatin dessert.

Legal definitions and regulations

China

Gelatin dessert in China is defined as edible jelly-like food prepared from a mixture of water, sugar and gelling agent.[18] The preparation processes include concocting, gelling, sterilizing and packaging. In China, around 250 legal additives are allowed in gelatin desserts as gelling agents, colors, artificial sweeteners, emulsifiers and antioxidants.[19]

Gelatin desserts are classified into 5 categories according to the different flavoring substances they contain. Five types of flavoring substance include artificial fruit flavored type (less than 15% of natural fruit juice), natural fruit flavored type (above 15% of natural fruit juice), natural flavored with fruit pulp type and dairy type products, which includes dairy ingredients. The last type (“others”) summarizes gelatin desserts not mentioned above. It is typically sold in single-serving plastic cups or plastic food bags.

Safety

.jpeg.webp)

Although eating tainted beef can lead to New Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (the human variant of mad-cow disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy), there is no known case of BSE having been transmitted through collagen products such as gelatin.[20]

Jelly worldwide

- Aam papad, a mango preserve from Indian subcontinent

- Almond jelly, a sweet dessert from Hong Kong

- Cedrate fruit, from Northern Iran, is made into a jam called morabbā-ye bālang

- Chakkavaratti, a Southern Indian jackfruit preserve made with jaggery.

- Coffee jelly features in many desserts in Japan

- Jellied cranberry sauce is primarily a holiday treat in the U.S. and the UK.

- Götterspeise, a German dessert made of gelatine or other gelling agent

- Grass jelly, a food from China and Southeast Asia, often served in drinks

- Bocadillo, a Latin American confectionery made with guava pulp and panela

- Hitlerszalonna ('Hitler's bacon'), sold today as gyümölcs íz. The original name comes from the scarcity of real bacon during wartime. This dense fruit jam was eaten by Hungarian troops and civilians during World War II. It was made from mixed fruits such as plum and sold in brick-shaped blocks.

- Konjac, a variety of Japanese jelly made from konnyaku

- Jell-O was named the official snack food of the U.S. state of Utah in 2001. A bowl of lime flavored gelatin was featured on a pin for the 2002 Winter Olympics held in Salt Lake City.

- Mayhaw jelly is a delicacy in parts of the American South.

- Muk, a variety of Korean jelly, seasoned and eaten as a cold salad

- Nata de coco, jelly made from coconuts originating from the Philippines

- Turkish delight, a jelly type of Turkish dessert

- Yōkan, a sweet, pasty jelly dessert from Japan often made with beans, sweet potato or squash

See also

- Aspic

- Jello salad, a variation on gelatin desserts that include other ingredients

- Jelly bean

- List of desserts

References

- The Picayune (2013). The Picayune's Creole Cook Book. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-4494-4043-5. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017.

- Glasse, Hannah (1774). To make hartshorn jelly. The Art of Cookery (1774 ed.). Printed for W. Strahan, J. and F. Rivington, J. Hinton. p. 285.

- "A Social History of Jell-O Salad: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon". Seriouseats.com.

- "Miscellaneana: Savoring antique jelly molds". liveauctioneers.com. 30 October 2015.

- "Unflavored Gelatin – Using Gelatin In Your Cooking". Archived from the original on 26 April 2010.

- Francis, Frederick J (2000). Encyclopedia of Food Science and Technology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1183–1188.

- "That Was the Wit That Was". SF Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- Thomas, Jerry (1928). How to Mix Drinks, Or, The Bon-vivant's Companion. Dick & Fitzgerald. p. 24.

- The Joy of Mixology by Gary Regan. Clarkson Potter, 2003. pp. 15–16, 150.

- "All About Agar" Archived 3 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Agar Plates Bacterial Culture". Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- "Gelation and Stiffening Power of Gelatin". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- Pareño, Roel (14 September 2011). "DA: Phl to regain leadership in seaweed production". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Buschmann, Alejandro H.; Camus, Carolina; Infante, Javier; Neori, Amir; Israel, Álvaro; Hernández-González, María C.; Pereda, Sandra V.; Gomez-Pinchetti, Juan Luis; Golberg, Alexander; Tadmor-Shalev, Niva; Critchley, Alan T. (2 October 2017). "Seaweed production: overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity". European Journal of Phycology. 52 (4): 391–406. doi:10.1080/09670262.2017.1365175. ISSN 0967-0262. S2CID 53640917.

- Montaño, Marco Nemesio E. (16 September 2004). "Gelatin, gulaman, 'JellyAce,' atbp". PhilStar Global. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Things you need to know about gelatine". Food Magazine-Philippines: 99. 12 November 2021.

- "What is Jell-O? How does it turn from a liquid to a solid when it cools?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "GB 2760-2014 食品安全国家标准 食品添加剂使用标准". gb2760.chinafoodsafety.net. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory Committee (SEAC) (1992–2000). "BSE inquiry: A consideration of the possible hazard of gelatin to man". Archived from the original on 28 February 2006.