General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the head of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). From 1929 until the union's dissolution, the holder of the office was the de facto leader of the Soviet Union,[2] because the post controlled the party, the foreign and the internal politics of the state and the federal government. It was the de facto highest ranking office of the Union.

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

|---|---|

| Генеральный секретарь ЦК КПСС | |

Emblem of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| Central Committee of the Communist Party | |

| Style | Comrade General Secretary (informal) |

| Type | Party leader |

| Status | Country leader |

| Member of |

|

| Residence | Kremlin Senate[1] |

| Seat | Kremlin, Moscow |

| Appointer | Central Committee |

| Formation | 3 April 1922 |

| First holder | Joseph Stalin |

| Final holder | Vladimir Ivashko (acting) |

| Abolished | 29 August 1991 |

| Superseded by | Chairman of the Union of Communist Parties |

| Salary | 10,000 Rbls annually |

History

Before the October Revolution, the job of the party secretary was largely that of a bureaucrat. Following the Bolshevik seizure of power, the Office of the Responsible Secretary was established in 1919 to perform administrative work.[3] After the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War, the Office of General Secretary was created by Vladimir Lenin in 1922 with the intention that it serve a purely administrative and disciplinary purpose. Its primary task would be to determine the composition of party membership and to assign positions within the party. The General Secretary also oversaw the recording of party events, and was entrusted with keeping party leaders and members informed about party activities. When assembling his cabinet, Lenin appointed Joseph Stalin to be General Secretary. Over the next few years, Stalin was able to use the principles of democratic centralism to transform his office into that of party leader, and eventually leader of the Soviet Union.[4]

Prior to Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin's tenure as General Secretary was already being criticized.[5] In Lenin's final months, he authored a pamphlet that called for Stalin's removal on the grounds that Stalin was becoming authoritarian and abusing his power. The pamphlet triggered a political crisis which endangered Stalin's position as General Secretary, and a vote was held to remove him from office. With the help of Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, Stalin was able to survive the scandal and remained in his post. After Lenin's death, Stalin began to consolidate his power by using the office of General Secretary. By 1928, he had unquestionably become the de facto leader of the USSR, while the position of General Secretary became the highest office in the nation. In 1934, the 17th Party Congress refrained from formally re-electing Stalin as General Secretary. However, Stalin was re-elected to all the other positions he held, and remained leader of the party without diminution.[6]

In the 1950s, Stalin increasingly withdrew from Secretariat business, leaving the supervision of the body to Georgy Malenkov, possibly to test his abilities as a potential successor.[7] In October 1952, at the 19th Party Congress, Stalin restructured the party's leadership. His request, voiced through Malenkov, to be relieved of his duties in the party secretariat due to his age, was rejected by the party congress, as delegates were unsure about Stalin's intentions.[8] In the end, the congress formally abolished Stalin's office of General Secretary, although Stalin remained one of the party secretaries and maintained ultimate control of the party.[9][10] When Stalin died on 5 March 1953, Malenkov was considered to be the most important member of the Secretariat, which also included Nikita Khrushchev, among others. Under a short-lived troika consisting of Malenkov, Beria, and Molotov, Malenkov became Chairman of the Council of Ministers, but was forced to resign from the Secretariat nine days later on 14 March. This effectively left Khrushchev in control of the government,[11] and he was elected to the new office of First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at the Central Committee plenum on 14 September that same year. Khrushchev subsequently outmanoeuvred his rivals, who sought to challenge his political reforms. He was able to comprehensively remove Malenkov, Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich (one of Stalin's oldest and closest associates) from power in 1957, an achievement which also helped to reinforce the supremacy of the position of First Secretary.[12]

In 1964, opposition within the Politburo and the Central Committee, which had been increasing since the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, led to Khrushchev's removal from office. Leonid Brezhnev succeeded Khrushchev as First Secretary, but was initially obliged to govern as part of a collective leadership, forming another troika with Premier Alexei Kosygin and Chairman Nikolai Podgorny.[13] The office was renamed to General Secretary in 1966.[14] The collective leadership was able to limit the powers of the General Secretary during the Brezhnev Era.[15] Brezhnev's influence grew throughout the 1970s as he was able to retain support by avoiding any radical reforms.[16] After Brezhnev's death, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko were able to rule the country in the same way as Brezhnev had.[17] Mikhail Gorbachev ruled the Soviet Union as General Secretary until 1990, when the Communist Party lost its monopoly of power over the political system. The office of President of the Soviet Union was established so that Gorbachev could still retain his role as leader of the Soviet Union.[18] Following the failed August coup of 1991, Gorbachev resigned as General Secretary.[19] He was succeeded by his deputy, Vladimir Ivashko, who only served for five days as Acting General Secretary before Boris Yeltsin, the newly elected President of Russia, suspended all activity in the Communist Party.[20] Following the party's ban, the Union of Communist Parties – Communist Party of the Soviet Union (UCP–CPSU) was established by Oleg Shenin in 1993, and is dedicated to reviving and restoring the CPSU. The organisation has members in all the former Soviet republics.[21]

List of officeholders

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Term | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | Duration | |||

| Technical Secretary of the Social Democratic Labour Party of Russia (1917–1918) | |||||

|

Elena Stasova (1873–1966)[22] |

April 1917 | 1918 | 0–1 years | As Technical Secretary, Stasova and her staff of four women were responsible for maintaining correspondence with provincial party cells, assigning work, keeping financial records, distributing Party funds,[23] formulating party structure policy and appointing new personnel.[24] |

| Chairperson of the Russian Communist Party (1918–1919) | |||||

|

Yakov Sverdlov (1885–1919)[25] |

1918 | 16 March 1919 † | 0–1 years | Sverdlov remained in office until his death on 16 March 1919. During his tenure he was mainly responsible for technical rather than political matters.[26] |

|

Elena Stasova (1873–1966)[22] |

March 1919 | December 1919 | 9 months | When her office was dissolved, Stasova was not considered a serious competitor for the post of Responsible Secretary, the successor office to the Chairman of the Secretariat.[27] |

| Responsible Secretary of the Russian Communist Party (1919–1922) | |||||

|

Nikolay Krestinsky (1883–1938)[28] |

December 1919 | March 1921 | 1 year, 3 months | The office of Responsible Secretary functioned like a secretary, a somewhat menial position given that Krestinsky was also a member of the Party's Politburo, Orgburo and Secretariat. Nevertheless, Krestinsky never tried to create an independent power base as Joseph Stalin later did during his time as General Secretary.[3] |

|

Vyacheslav Molotov (1890–1986)[29] |

16 March 1921 | 3 April 1922 | 291 days | Was elected Responsible Secretary at the 10th Party Congress held in March 1921. The Congress decided that the office of Responsible Secretary should have a presence at Politburo plenums. As a result, Molotov became a candidate member of the Politburo.[30] |

| General Secretary of the All-Union Communist Party (1922–1952) | |||||

|

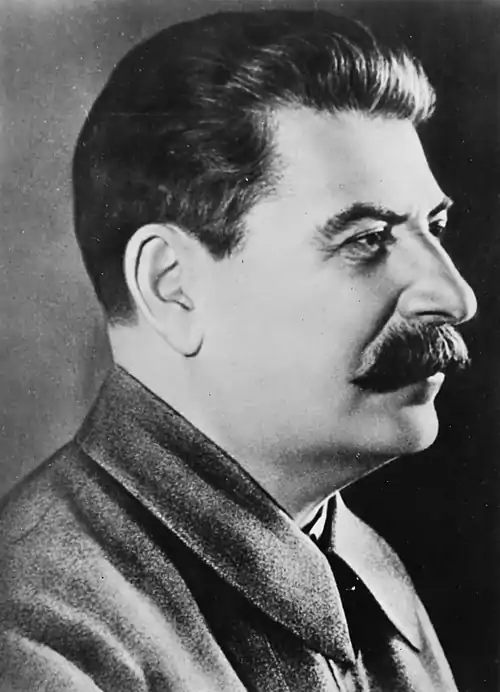

Joseph Stalin (1878–1953)[31] |

3 April 1922 | 16 October 1952 | 30 years, 196 days | Stalin used the office of General Secretary to create a strong power base for himself. At the 17th Party Congress in 1934, Stalin was not formally re-elected as General Secretary[32] and the office was rarely mentioned after that[33] but Stalin retained his positions and all of his power. The office was formally abolished at the 19th Party Congress on 16 October 1952, but Stalin retained ultimate power and his position as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[10] At 30 years 7 months, Stalin was by far the longest-serving General Secretary, serving for almost half of the USSR's entire existence. |

| First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1953–1966) | |||||

|

Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971)[34] |

14 September 1953 | 14 October 1964 | 11 years, 30 days | Khrushchev reestablished the office on 14 September 1953 under the name First Secretary. In 1957, he was nearly removed from office by the Anti-Party Group. Georgy Malenkov, a leading member of the Anti-Party Group, worried that the powers of the First Secretary were virtually unlimited.[35] Khrushchev was removed as leader on 14 October 1964, and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev.[14] |

|

Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982)[36] |

14 October 1964 | 8 April 1966 | 1 year, 176 days | Brezhnev was part of a collective leadership with Premier Alexei Kosygin and others.[13] The office of First Secretary was renamed General Secretary at the 23rd Party Congress.[15] |

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1966–1991) | |||||

|

Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982)[36] |

8 April 1966 | 10 November 1982 † | 16 years, 216 days | Brezhnev's powers and functions as the General Secretary were limited by the collective leadership.[16] By the 1970s, Brezhnev's influence exceeded that of Kosygin as he was able to retain support by avoiding any radical reforms. |

|

Yuri Andropov (1914–1984)[37] |

12 November 1982 | 9 February 1984 † | 1 year, 89 days | He emerged as Brezhnev's most likely successor as the chairman of the committee in charge of managing Brezhnev's funeral.[38] Andropov ruled the country in the same way Brezhnev had before he died.[17] |

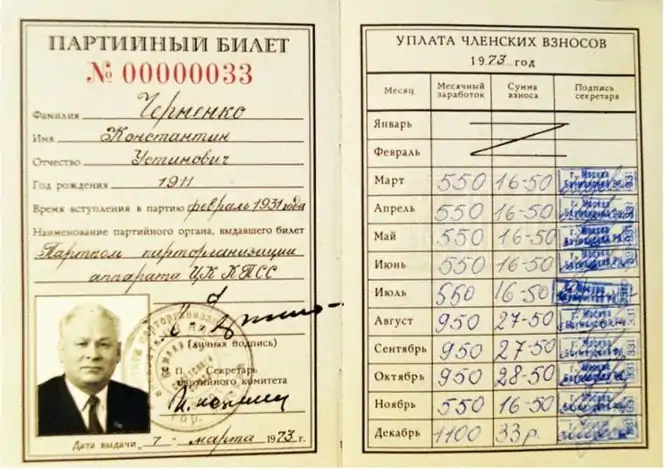

| Konstantin Chernenko (1911–1985)[36] |

13 February 1984 | 10 March 1985 † | 1 year, 25 days | Chernenko was 72 years old when elected to the post of General Secretary and in rapidly failing health.[39] Like Andropov, Chernenko ruled the country in the same way Brezhnev had.[17] | |

.png.webp) |

Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–2022)[40] |

11 March 1985 | 24 August 1991 | 6 years, 166 days | The 1990 Congress of People's Deputies removed Article 6 from the 1977 Soviet Constitution resulting in the Communist Party loss of its position as the "leading and guiding force of the Soviet society." The powers of the General Secretary were drastically curtailed. Throughout the rest of his tenure, Gorbachev ruled through the office of President of the Soviet Union.[18] He resigned from his party office on 24 August 1991 in the aftermath of the August Coup.[19] |

_(cropped).JPG.webp) |

Vladimir Ivashko (1932–1994) Acting[41] |

24 August 1991 | 29 August 1991 | 5 days | He was elected Deputy General Secretary at the 28th Party Congress. Ivashko became acting General Secretary following Gorbachev's resignation, but by then the Party was politically impotent. Its activities were suspended on 29 August 1991,[20] and it was banned on 6 November.[42] |

See also

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

- General Secretary of the Communist Party

- General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party

- General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam

- General Secretary of the Workers' Party of Korea

- First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba

- President of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia

Notes

- "ГЛАВНЫЙ КОРПУС КРЕМЛЯ". The VVM Library. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Armstrong 1986, p. 93.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 126.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 142–146.

- "What Lenin's Critics Got Right". Dissent Magazine. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "Secretariat, Orgburo, Politburo and Presidium of the CC of the CPSU in 1919–1990 – Izvestia of the CC of the CPSU" (in Russian). 7 November 1990. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Z. Medvedev & R. Medvedev 2006, p. 40.

- Z. Medvedev & R. Medvedev 2006, p. 40-41.

- Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939 – 1953, p. 345.

- Brown 2009, pp. 231–232.

- Ra'anan 2006, pp. 29–31.

- Ra'anan 2006, p. 58.

- Brown 2009, p. 403.

- Service 2009, p. 378.

- McCauley 1997, p. 48.

- Baylis 1989, pp. 98–99 & 104.

- Baylis 1989, p. 98.

- Kort 2010, p. 394.

- Radetsky 2007, p. 219.

- McCauley 1997, p. 105.

- Backes & Moreau 2008, p. 415.

- McCauley 1997, p. 117.

- Clements 1997, p. 140.

- Fairfax 1999, p. 36.

- Williamson 2007, p. 42.

- Zemtsov 2001, p. 132.

- Noonan 2001, p. 183.

- Rogovin 2001, p. 38.

- Phillips 2001, p. 20.

- Grill 2002, p. 72.

- Brown 2009, p. 59.

- Rappaport 1999, pp. 95–96.

- Ulam 2007, p. 734.

- Taubman 2003, p. 258.

- Ra'anan 2006, p. 69.

- Chubarov 2003, p. 60.

- Vasil'eva 1994, pp. 218.

- White 2000, p. 211.

- Service 2009, pp. 433–435.

- Service 2009, p. 435.

- McCauley 1998, p. 314.

- Указ Президента РСФСР от 6 ноября 1991 г. № 169 «О деятельности КПСС и КП РСФСР»

Sources

- Armstrong, John Alexander (1986). Ideology, Politics, and Government in the Soviet Union: An Introduction. University Press of America. ASIN B002DGQ6K2.

- Backes, Uwe; Moreau, Patrick (2008). Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8.

- Baylis, Thomas A. (1989). Governing by Committee: Collegial Leadership in Advanced Societies. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-944-4.

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism. Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0061138799.

- Chubarov, Alexander (2003). Russia's Bitter Path to Modernity: A History of the Soviet and post-Soviet Eras. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0826413505.

- Clements, Barbara Evans (1997). Bolshevik Women. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521599207.

- Fainsod, Merle; Hough, Jerry F. (1979). How the Soviet Union is Governed. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674410305.

- Fairfax, Kaithy (1999). Comrades in Arms: Bolshevik Women in the Russian Revolution. Resistance Books. ISBN 090919694X.

- Grill, Graeme (2002). The Origins of the Stalinist Political System. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521529365.

- March, Luke (2002). The Communist Party In Post-Soviet Russia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6044-1.

- Kort, Michael (2010). The Soviet Colossus: History and Aftermath. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-2387-4.

- McCauley, Martin (1998). Gorbachev. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0582437586.

- McCauley, Martin (1997). Who's who in Russia since 1900. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13898-1.

- Medvedev, Zhores; Medvedev, Roy (2006). The Unknown Stalin. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1585675029.

- Noonan, Norma (2001). Encyclopedia of Russian Women's Movements. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313304385.

- Phillips, Steve (2001). The Cold War: conflict in Europe and Asia. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0435327361.

- Ra'anan, Uri (2006). Flawed Succession: Russia's Power Transfer Crises. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739114025.

- Radetsky, Peter (2007). The Soviet Image: A Hundred Years of Photographs from Inside the TASS Archives. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0811857987.

- Rappaport, Helen (1999). Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576070840.

- Rogovin, Vadim (2001). Stalin's Terror of 1937–1938: Political Genocide in the USSR. Mehring Books. ISBN 978-1893638082.

- Service, Robert (2009). History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-first Century. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0674034938.

- Taubman, William (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393051445.

- Ulam, Adam (2007). Stalin: The Man and His Era. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1-84511-422-0.

- Vasilʹeva, Larisa Nikolaevna (1994). Kremlin Wives. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1559702607.

- White, Stephen (2000). Russia's New Politics: The Management of a Postcommunist Society. Cambridge University Press. ASIN B003QI0DQE.

- Williamson, D.G. (2007). The Age of the Dictators: A Study of the European Dictatorships, 1918–53 (1st ed.). Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0582505803.

- Zemtsov, Ilya (2001). Encyclopedia of Soviet Life. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0887383502.