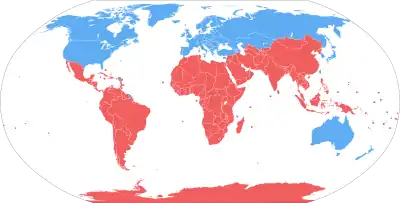

Global North and Global South

The concept of Global North and Global South (or North–South divide in a global context) is used to describe a grouping of countries along socio-economic and political characteristics. The Global South is a term often used to identify regions within Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. It is one of a family of terms, including "Third World" and "Periphery", that denote regions outside Europe and North America. Most, though not all, of these countries are low-income and often politically or culturally marginalized on one side of the divide, while on the other side are the countries of the Global North (often equated with developed countries).[1] As such, the term does not inherently refer to a geographical south; for example, most of the Global South is geographically within the Northern Hemisphere.[1]

The term as used by governmental and developmental organizations was first introduced as a more open and value-free alternative to "Third World"[2] and similarly potentially "valuing" terms like developing countries. Countries of the Global South have been described as newly industrialized or in the process of industrializing, and are frequently current or former subjects of colonialism.[3]

The Global North mostly correlates with the Western world—with the notable exceptions of Israel, Japan, and South Korea— and the South largely corresponds with the developing countries previously called "Third World," plus the Eastern world. Geographically, the Global South is mostly composed of regions that are neither Western nor Eastern such as the Latin Westand most African countries. The two groups are often defined in terms of their differing levels of wealth, economic development, income inequality, democracy, and political and economic freedom, as defined by freedom indices. States that are generally seen as part of the Global North tend to be wealthier and less unequal with large, well-developed infrastructure as well as advanced technology, manufacturing and energy industries. Southern states are generally developing countries with younger institutions. They tend to be heavily dependent on primary sector exports. The divide between the North and the South is often challenged.[4]

Global South leaders became more assertive in world politics in the 1990s, a trend that has continued into the 2020s with massive trillion-dollar initiatives such as China's BNR (Belt and Road Initiative). South-South cooperation has increased to "challenge the political and economic dominance of the North."[5][6][7] This cooperation has become a popular political and economic concept following geographical migrations of manufacturing and production activity from the North to the Global South[7] and the diplomatic action of several states, like China.[7] These contemporary economic trends have "enhanced the historical potential of economic growth and industrialization in the Global South," which has renewed targeted SSC efforts that "loosen the strictures imposed during the colonial era and transcend the boundaries of postwar political and economic geography."[8] Used in several books and American Literature special issue, the term Global South, recently became prominent for U.S. literature.[9]

Definition

.png.webp)

|

0.800–1.000 (very high)

0.700–0.799 (high)

0.550–0.699 (medium) |

0.350–0.549 (low)

Data unavailable |

The terms are not strictly geographical, and are not "an image of the world divided by the equator, separating richer countries from their poorer counterparts."[1] Rather, geography should be more readily understood as economic and migratory, the world understood through the "wider context of globalization or global capitalism."[1]

Generally, definitions of the Global North is not exclusively a geographical term, and it includes countries and areas such as Australia, Canada, the entirety of Europe and Russia, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and the United States.[10][11] The Global South is made up of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Pacific Islands, and Asia, excluding Israel, Japan, and South Korea.[10][11] It is generally seen as home to Brazil, India, Indonesia and China, which, along with Nigeria and Mexico, are the largest Southern states in terms of land area and population.[12]

The overwhelming majority of the Global South countries are located in or near the tropics.

The term Global North is often used interchangeably with developed countries. Likewise, the term Global South is often used interchangeably with developing countries.

Society and culture

Digital and technological divide

The global digital divide is often characterized as corresponding to the north–south divide;[13] however, Internet use, and especially broadband access, is now soaring in Asia compared with other continents. This phenomenon is partially explained by the ability of many countries in Asia to leapfrog older Internet technology and infrastructure, coupled with booming economies which allow vastly more people to get online.[14]

Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China has stated that it intends to invest heavily in augmenting the technological landscape in countries like Kenya and Peru.

Religion and spirituality

Spirituality tends to be more widespread in the Global South than in the Global North. Countries like Nepal and Brazil are known for their ubiquitous religious presence while India[15] is regarded as the birthplace of four of the world's major religions, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. In 2013, the election of Pope Francis from Argentina marked the first time in history that a pope has been elected from the Global South.

Outside of the major religions, most of the world's indigenous population live in the Global South. Africa is home to more than 3,000 ethnic groups,[16] while Latin America is home to more than 58 million indigenous people spread across 826 indigenous groups.[17] In 2015, the synthesis of an anti-malarial drug using an herb employed in Traditional Chinese Medicine was awarded a Nobel Prize For Medicine.[18]

Notable religions and spiritual traditions to have come from the Global South include:

- Islam - Saudi Arabia

- Hinduism - India

- Buddhism - India

- Sikhism - India

- Taoism - China

- Jainism - India

Media representation

When looking at media coverage of developing countries, a generalized view has developed through Western media. Negative images and coverage of the poverty are frequent in the mass media when talking about developing countries. This common coverage has created a dominant stereotype of developing countries as: "the 'South' is characterized by socioeconomic and political backwardness, measured against Western values and standards."[19] Mass media's role often compares the Global South to the North and is thought to be an aid in the divide.

Mass media has also played a role in what information the people in developing countries receive. The news often covers developed countries and creates an imbalance of information flow.[20] The people in developing countries do not often receive coverage of the other developing countries but instead gets generous amounts of coverage about developed countries.Development of the terms

The first use of Global South in a contemporary political sense was in 1969 by Carl Oglesby, writing in Catholic journal Commonweal in a special issue on the Vietnam War. Oglesby argued that centuries of northern "dominance over the global south […] [has] converged […] to produce an intolerable social order."[21]

The term gained appeal throughout the second half of the 20th century, which rapidly accelerated in the early 21st century. It appeared in fewer than two dozen publications in 2004, but in hundreds of publications by 2013.[22] The emergence of the new term meant looking at the troubled realities of its predecessors, i.e.: Third World or Developing World. The term "Global South", in contrast, was intended to be less hierarchical.[1]

The idea of categorizing countries by their economic and developmental status began during the Cold War with the classifications of East and West. The Soviet Union and China represented the East, and the United States and their allies represented the West. The term Third World came into parlance in the second half of the twentieth century. It originated in a 1952 article by Alfred Sauvy entitled "Trois Mondes, Une Planète".[23] Early definitions of the Third World emphasized its exclusion from the east–west conflict of the Cold War as well as the ex-colonial status and poverty of the peoples it comprised.[23]

Efforts to mobilize the Third World as an autonomous political entity were undertaken. The 1955 Bandung Conference was an early meeting of Third World states in which an alternative to alignment with either the Eastern or Western Blocs was promoted.[23] Following this, the first Non-Aligned Summit was organized in 1961. Contemporaneously, a mode of economic criticism which separated the world economy into "core" and "periphery" was developed and given expression in a project for political reform which "moved the terms 'North' and 'South' into the international political lexicon."[24]

In 1973, the pursuit of a New International Economic Order which was to be negotiated between the North and South was initiated at the Non-Aligned Summit held in Algiers.[25] Also in 1973, the oil embargo initiated by Arab OPEC countries as a result of the Yom Kippur War caused an increase in world oil prices, with prices continuing to rise throughout the decade.[26] This contributed to a worldwide recession which resulted in industrialized nations increasing economically protectionist policies and contributing less aid to the less developed countries of the South.[26] The slack was taken up by Western banks, which provided substantial loans to Third World countries.[27] However, many of these countries were not able to pay back their debt, which led the IMF to extend further loans to them on the condition that they undertake certain liberalizing reforms.[27] This policy, which came to be known as structural adjustment, and was institutionalized by International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and Western governments, represented a break from the Keynesian approach to foreign aid which had been the norm from the end of the Second World War.[27]

After 1987, reports on the negative social impacts that structural adjustment policies had had on affected developing nations led IFIs to supplement structural adjustment policies with targeted anti-poverty projects.[4] Following the end of the Cold War and the break-up of the Soviet Union, some Second World countries joined the First World, and others joined the Third World. A new and simpler classification was needed. Use of the terms "North" and "South" became more widespread.

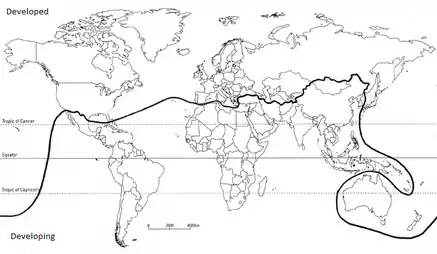

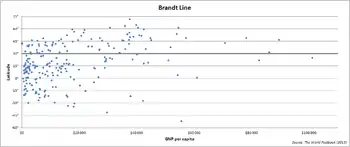

Brandt Line

The Brandt Line is a visual depiction of the north–south divide, proposed by West German former Chancellor Willy Brandt in the 1980s in the report titled North-South: A Programme for Survival which was later known as the Brandt Report.[28] This line divides the world at a latitude of approximately 30° North, passing between the United States and Mexico, north of Africa and the Middle East, climbing north over China and Mongolia, but dipping south to include Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the city-state of Singapore in the "Rich North".

Uses of the term Global South

Global South "emerged in part to aid countries in the southern hemisphere to work in collaboration on political, economic, social, environmental, cultural, and technical issues."[8][29] This is called South–South cooperation (SSC), a "political and economical term that refers to the long-term goal of pursuing world economic changes that mutually benefit countries in the Global South and lead to greater solidarity among the disadvantaged in the world system."[8][29] The hope is that countries within the Global South will "assist each other in social, political, and economical development, radically altering the world system to reflect their interests and not just the interests of the Global North in the process."[8] It is guided by the principles of "respect for national sovereignty, national ownership, independence, equality, non-conditionality, non-interference in domestic affairs, and mutual benefit."[5][6] Countries using this model of South–South cooperation see it as a "mutually beneficial relationship that spreads knowledge, skills, expertise and resources to address their development challenges such as high population pressure, poverty, hunger, disease, environmental deterioration, conflict and natural disasters."[5][6] These countries also work together to deal with "cross border issues such as environmental protection, HIV/AIDS,"[5][6] and the movement of capital and labor.[5][6]

Social psychiatrist Vincenzo Di Nicola has applied the Global South as a bridge between the critiques globalization and the gaps and limitations of the Global Mental Health Movement invoking Boaventura de Sousa Santos' notion of "epistemologies of the South" to create a new epistemology for social psychiatry.[30]

Defining development

Being categorized as part of the "North" implies development as opposed to belonging to the "South", which implies a lack thereof. According to N. Oluwafemi Mimiko, the South lacks the right technology, it is politically unstable, its economies are divided, and its foreign exchange earnings depend on primary product exports to the North, along with the fluctuation of prices. The low level of control it exercises over imports and exports condemns the South to conform to the 'imperialist' system. The South's lack of development and the high level of development of the North deepen the inequality between them and leave the South a source of raw material for the developed countries.[31][3] The north becomes synonymous with economic development and industrialization while the South represents the previously colonized countries which are in need of help in the form of international aid agendas.[32] In order to understand how this divide occurs, a definition of "development" itself is needed. Northern countries are using most of the earth resources and most of them are high entropic fossil fuels. Reducing emission rates of toxic substances is central to debate on sustainable development but this can negatively affect economic growth.

The Dictionary of Human Geography defines development as "processes of social change or [a change] to class and state projects to transform national economies".[33] This definition entails an understanding of economic development which is imperative when trying to understand the north–south divide.

Economic Development is a measure of progress in a specific economy. It refers to advancements in technology, a transition from an economy based largely on agriculture to one based on industry and an improvement in living standards.[34]

Other factors that are included in the conceptualization of what a developed country is include life expectancy and the levels of education, poverty and employment in that country.

Furthermore, in Regionalism Across the North-South Divide: State Strategies and Globalization, Jean Grugel states that the three factors that direct the economic development of states within the Global south is "élite behaviour within and between nation states, integration and cooperation within 'geographic' areas, and the resulting position of states and regions within the global world market and related political economic hierarchy."[35]

Theories explaining the divide

The development disparity between the North and the South has sometimes been explained in historical terms. Dependency theory looks back on the patterns of colonial relations which persisted between the North and South and emphasizes how colonized territories tended to be impoverished by those relations.[27] Theorists of this school maintain that the economies of ex-colonial states remain oriented towards serving external rather than internal demand, and that development regimes undertaken in this context have tended to reproduce in underdeveloped countries the pronounced class hierarchies found in industrialized countries while maintaining higher levels of poverty.[27] Dependency theory is closely intertwined with Latin American Structuralism, the only school of development economics emerging from the Global South to be affiliated with a national research institute and to receive support from national banks and finance ministries.[36] The Structuralists defined dependency as the inability of a nation's economy to complete the cycle of capital accumulation without reliance on an outside economy.[37] More specifically, peripheral nations were perceived as primary resource exporters reliant on core economies for manufactured goods.[38] This led structuralists to advocate for import-substitution industrialization policies which aimed to replace manufactured imports with domestically made products.[36]

New Economic Geography explains development disparities in terms of the physical organization of industry, arguing that firms tend to cluster in order benefit from economies of scale and increase productivity which leads ultimately to an increase in wages.[39] The North has more firm clustering than the South, making its industries more competitive. It is argued that only when wages in the North reach a certain height, will it become more profitable for firms to operate in the South, allowing clustering to begin.

Associated theories

The term of the Global South has many researched theories associated with it. Since many of the countries that are considered to be a part of the Global South were first colonized by Global North countries, they are at a disadvantage to become as quickly developed. Dependency theorists suggest that information has a top-down approach and first goes to the Global North before countries in the Global South receive it. Although many of these countries rely on political or economic help, this also opens up opportunity for information to develop Western bias and create an academic dependency.[40] Meneleo Litonjua describes the reasoning behind distinctive problems of dependency theory as "the basic context of poverty and underdevelopment of Third World/Global South countries was not their traditionalism, but the dominance-dependence relationship between rich and poor, powerful and weak counties."[27]

What brought about much of the dependency, was the push to become modernized. After World War II, the U.S. made effort to assist developing countries financially in attempt to pull them out of poverty.[41] Modernization theory "sought to remake the Global South in the image and likeliness of the First World/Global North."[27] In other terms, "societies can be fast-tracked to modernization by 'importing' Western technical capital, forms of organization, and science and technology to developing countries." With this ideology, as long as countries follow in Western ways, they can develop quicker.

After modernization attempts took place, theorists started to question the effects through post-development perspectives. Postdevelopment theorists try to explain that not all developing countries need to be following Western ways but instead should create their own development plans. This means that "societies at the local level should be allowed to pursue their own development path as they perceive it without the influences of global capital and other modern choices, and thus a rejection of the entire paradigm from Eurocentric model and the advocation of new ways of thinking about the non-Western societies."[42] The goals of postdevelopment was to reject development rather than reform by choosing to embrace non-Western ways.[43]

Challenges

The accuracy of the North–South divide has been challenged on a number of grounds. Firstly, differences in the political, economic and demographic make-up of countries tend to complicate the idea of a monolithic South.[23] Globalization has also challenged the notion of two distinct economic spheres. Following the liberalization of post-Mao China initiated in 1978, growing regional cooperation between the national economies of Asia has led to the growing decentralization of the North as the main economic power.[44] The economic status of the South has also been fractured. As of 2015, all but roughly the bottom 60 nations of the Global South were thought to be gaining on the North in terms of income, diversification, and participation in the world market.[39]

Globalization has largely displaced the North–South divide as the theoretical underpinning of the development efforts of international institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, WTO, and various United Nations affiliated agencies, though these groups differ in their perceptions of the relationship between globalization and inequality.[4] Yet some remain critical of the accuracy of globalization as a model of the world economy, emphasizing the enduring centrality of nation-states in world politics and the prominence of regional trade relations.[38]

The divide between the North and South challenges international environmental cooperation. The economic differences between North and South have created dispute over the scientific evidence and data regarding global warming and what needs to be done about it. As the South don't trust Northern data and cannot afford the technology to be able to produce their own. In addition to these disputes, there are serious divisions over responsibility, who pays, and the possibility for the South to catch up. This is becoming an ever-growing issue with the emergence of rising powers, imploding these three divisions just listed and making them progressively blurry. Multiplicity of actors, such as governments, businesses, and NGO's all influence any positive activity that can be taken into preventing further global warming problems with the Global North and Global South divide contributing to the severity of said actors. Disputes between Northern countries governments and Southern countries governments has led to a break down in international discussions with governments from either side disagreeing with each other. Addressing most environmental problems requires international cooperation, and the North and South contribute to the stagnation concerning any form of implementation and enforcement, which remains a key issue.

Debates over the term

With its development, many scholars preferred using the Global South over its predecessors, such as "developing countries" and "Third World". Leigh Anne Duck, co-editor of Global South, argued that the term is better suited at resisting "hegemonic forces that threaten the autonomy and development of these countries."[45] Alvaro Mendez, co-founder of the London School of Economics and Political Science's Global South Unit, have applauded the empowering aspects of the term. In an article, Discussion on Global South, Mendez discusses emerging economies in nations like China, India and Brazil. It is predicted that by 2030, 80% of the world's middle-class population will be living in developing countries.[46] The popularity of the term "marks a shift from a central focus on development and cultural difference" and recognizes the importance of geopolitical relations.[47]

Critics of this usage often argue that it is a vague blanket term".[48] Others have argued that the term, its usage, and its subsequent consequences mainly benefit those from the upper classes of countries within the Global South;[1] who stand "to profit from the political and economic reality [of] expanding south-south relations."[1]

According to scholar Anne Garland Mahler, this nation-based understanding of the Global South is regarded as an appropriation of a concept that has deeper roots in Cold War radical political thought.[49] In this political usage, the Global South is employed in a more geographically fluid way, referring to "spaces and peoples negatively impacted by contemporary capitalist globalization."[50] In other words, "there are economic Souths in the geographic North and Norths in the geographic South."[50] Through this geographically fluid definition, another meaning is attributed to the Global South where it refers to a global political community that is formed when the world's "Souths" recognize one another and view their conditions as shared.[51]

The geographical boundaries of the Global South remain a source of debate. Some scholars agree that the term is not a "static concept".[1] Others have argued against "grouping together a large variety of countries and regions into one category [because it] tends to obscure specific (historical) relationships between different countries and/or regions" and the power imbalances within these relationships.[1] This "may obscure wealth differences within countries – and, therefore, similarities between the wealthy in the Global South and Global North, as well as the dire situation the poor may face all around the world."[1]

Future development

Some economists have argued that international free trade and unhindered capital flows across countries could lead to a contraction in the North–South divide. In this case more equal trade and flow of capital would allow the possibility for developing countries to further develop economically.[52]

As some countries in the South experience rapid development, there is evidence that those states are developing high levels of South–South aid.[53] Brazil, in particular, has been noted for its high levels of aid ($1 billion annually—ahead of many traditional donors) and the ability to use its own experiences to provide high levels of expertise and knowledge transfer.[53] This has been described as a "global model in waiting".[54]

The United Nations has also established its role in diminishing the divide between North and South through the Millennium Development Goals, all of which were to be achieved by 2015. These goals seek to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, achieve global universal education and healthcare, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases, ensure environmental sustainability, and develop a global partnership for development.[55] There were replaced in 2015 by 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs, set in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly and intended to be achieved by 2030, are part of a UN Resolution called "The 2030 Agenda".[56]

See also

- BRICS, CIVETS, MINT, VISTA

- East–West dichotomy

- First World

- Golden billion

- Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world

- North–South Summit, the only North–South summit ever held, with 22 heads of state and government taking part

- North–South Centre, an institution of the Council of Europe, awarding the North–South Prize

- North–South model, in economics theory

- Sunshine countries

- Three-world model

- World-systems theory

References

- "Introduction: Concepts of the Global South". gssc.uni-koeln.de. Archived from the original on 2016-09-04. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- Mitlin, Diana; Satterthwaite, David (2013). Urban Poverty in the Global South: Scale and Nature. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 9780415624664.

- Mimiko, Nahzeem Oluwafemi (2012). Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business. Carolina Academic Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-61163-129-6.

- Therien, Jean-Philippe (2010). "Beyond the North-South divide: The two tales of world poverty". Third World Quarterly. 20 (4): 723–742. doi:10.1080/01436599913523. JSTOR 3993585.

- United Nations. "United Nations: Special Unit for South-South Cooperation" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-19.

- United Nations. "United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 2012-12-03.

- Acharya, Amitav (3 July 2016). "Studying the Bandung conference from a Global IR perspective". Australian Journal of International Affairs. 70 (4): 342–357. doi:10.1080/10357718.2016.1168359. S2CID 156589520.

- Gray, Kevin; Gills, Barry K. (2 April 2016). "South–South cooperation and the rise of the Global South". Third World Quarterly. 37 (4): 557–574. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1128817.

- Kim, Heidi Kathleen (2011). "The Foreigner in Yoknapatawpha: Rethinking Race in Faulkner's 'Global South'". Philological Quarterly. 90 (2/3): 199–228. OCLC 781730944. Gale A306971763 ProQuest 928757459.

- "UNCTADstat - Classifications".

- "What Is The North-South Divide?". worldatlas.com. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- Silver, Caleb. "The Top 20 Economies in the World". Investopedia. DotDash. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "The Global Digital Divide | Cultural Anthropology". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- "Internet penetration in Asia-Pacific 2019". Statista. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- Olivelle, Patrick. "Moksha | Indian religion". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Meet the Tribes in Africa | An Overview by Region". While in Africa.

- Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples. An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb2953en. ISBN 978-92-5-133970-1. S2CID 242184649.

- Manohar, P. Ram (October 2015). "Nobel prize, Traditional Chinese Medicine and Lessons for Ayurveda?". Ancient Science of Life. 35 (2): 67–69. doi:10.4103/0257-7941.171671. PMC 4728866. PMID 26865737.

- "Dependency Theory: A Useful Tool for Analyzing Global Inequalities Today?". E-International Relations. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- Philo, Greg (November 2001). "An unseen world: How the media portrays the poor". The UNESCO Courier. 54 (11): 44–46. ProQuest 207594362.

- Oglesby, Carl (1969). "Vietnamism has failed ... The revolution can only be mauled, not defeated". Commonweal. 90.

- Pagel, Heikie; Ranke, Karen; Hempel, Fabian; Köhler, Jonas (11 July 2014). "The Use of the Concept 'Global South' in Social Science & Humanities". Humboldt University of Berlin. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- Tomlinson, B.R. (April 2003). "What was the Third World?". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (2): 307–309. doi:10.1177/0022009403038002135. S2CID 162982648.

- Dados, Nour; Connell, Raewyn (February 2012). "The Global South". Contexts. 11 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1177/1536504212436479. S2CID 60907088.

- Cox, Robert W. (Spring 1979). "Ideologies and the New International Economic Order: Reflections on Some Recent Literature". International Organization. 33 (2): 257–302. doi:10.1017/S0020818300032161. JSTOR 2706612. S2CID 144625611.

- Stettner, Walter F. (Spring 1982). "The Brandt Commission Report: A Critical Appraisal". International Social Science Review. 57 (2): 67–81. JSTOR 41881303.

- Litonjua, M. D. (22 March 2012). "Third World/Global South: From Modernization, to Dependency/Liberation, to Postdevelopment". Journal of Third World Studies. 29 (1): 25–57. JSTOR 45194852. OCLC 8512965654. Gale A302297493.

- Lees, Nicholas (January 2021). "The Brandt Line after forty years: The more North–South relations change, the more they stay the same?". Review of International Studies. 47 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1017/S026021052000039X.

- "South-South Cooperation". Appropriate Technology. 40 (1): 45–48. March 2013. ProQuest 1326792037.

- Nicola, Vincenzo Di (1 January 2020). "The Global South: An Emergent Epistemology for Social Psychiatry". World Social Psychiatry. 2 (1): 20. doi:10.4103/WSP.WSP_1_20 (inactive 31 July 2022). Gale A641287561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - Mimiko, Nahzeem Oluwafemi (2012). Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business. Carolina Academic Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-61163-129-6.

- Preece, Julia (September 2009). "Lifelong learning and development: a perspective from the 'South'". Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 39 (5): 585–599. doi:10.1080/03057920903125602. S2CID 145584841.

- Gregory, Derek, Ron Johnston, Geraldine Pratt, Michael J. Watts, and Sarah Whatmore. The Dictionary of Human Geography. 5th. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Print.

- "Economic Development". Archived from the original on 2017-07-15.

- Grugel, Jean; Hout, Wil (1999-01-01). Regionalism Across the North-South Divide: State Strategies and Globalization. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415162128. Archived from the original on 2020-09-20. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- Love, Joseph Leroy (2005). "The Rise and Decline of Economic Structuralism in Latin America: New Dimensions". Latin American Research Review. 40 (3): 100–125. doi:10.1353/lar.2005.0058. JSTOR 3662824. S2CID 143132205.

- Caporaso, James A. (1980). "Dependency Theory: Continuities and Discontinuities in Development Studies". International Organization. 34 (4): 605–628. doi:10.1017/S0020818300018865. S2CID 153535159.

- Herath, Dhammika (2008). "Development Discourse of the Globalists and Dependency Theorists: Do the Globalisation Theorists Rephrase and Reword the Central Concepts of the Dependency School?". Third World Quarterly. 29 (4): 819–834. doi:10.1080/01436590802052961. S2CID 145570046.

- Collier, Paul (2015). "Development economics in retrospect and prospect". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 31 (2): 242–258. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grv013. hdl:10.1093/oxrep/grv013.

- Ruvituso, Clara I (January 2020). "From the South to the North: The circulation of Latin American dependency theories in the Federal Republic of Germany". Current Sociology. 68 (1): 22–40. doi:10.1177/0011392119885170.

- "America's Proud History of Post-War Aid – Foreign assistance after World War II proved critical to U.S. interests". US News. 6 June 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Olatunji, Felix O.; Bature, Anthony I. (September 2019). "The Inadequacy of Post-Development Theory to the Discourse of Development and Social Order in the Global South". Social Evolution & History. 18 (2). doi:10.30884/seh/2019.02.12.

- Matthews, Sally J. (2010). "Postdevelopment Theory". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.39. ISBN 978-0-19-084662-6.

- Golub, Philip S (July 2013). "From the New International Economic Order to the G20: how the 'global South' is restructuring world capitalism from within". Third World Quarterly. 34 (6): 1000–1015. doi:10.1080/01436597.2013.802505. S2CID 54170990.

- "Introduction: Concepts of the Global South | GSSC". 2016-09-04. Archived from the original on 2016-09-04. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "Discussion on the Global South | GSSC". 2016-10-26. Archived from the original on 2016-10-26. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Dados, Nour; Connell, Raewyn (February 2012). "The Global South" (PDF). Contexts. 11 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1177/1536504212436479. JSTOR 41960738. S2CID 60907088. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-19.

- Eriksen, Thomas Hylland (January 2015). "What´s wrong with the Global North and the Global South?". Global South Studies Center. Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- Mahler, Anne Garland (2018). From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity. Durham: Duke UP.

- Mahler, Anne Garland. "Global South." Oxford Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory, ed. Eugene O'Brien. Oxford 2017; Mahler, Anne Garland. "Global South." Global South Studies 2017: https://globalsouthstudies.as.virginia.edu/what-is-global-south

- López, Alfred J., ed. 2007. The Global South 1 (1).

- Reuveny, Rafael X.; Thompson, William R. (2007). "The North-South Divide and International Studies: A Symposium". International Studies Review. 9 (4): 556–564. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2007.00722.x. JSTOR 4621859.

- Cabral and Weinstock 2010. Brazil: an emerging aid player Archived 2012-03-22 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- Cabral, Lidia 2010. Brazil's development cooperation with the South: a global model in waiting Archived 2011-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". www.un.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-24. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- United Nations (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1)

External links

- Share The World's Resources: The Brandt Commission Report, a 1980 report by a commission led by Willy Brandt that popularized the terminology

- Brandt 21 Forum, a recreation of the original commission with an updated report (information on original commission at site)