Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

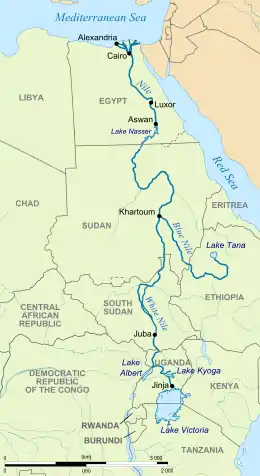

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD or TaIHiGe; Amharic: ታላቁ የኢትዮጵያ ሕዳሴ ግድብ, romanized: Tālāqu ye-Ītyōppyā Hidāsē Gidib, Oromo: Hidha Haaromsaa Guddicha Itoophiyaa[6]), formerly known as the Millennium Dam and sometimes referred to as Hidase Dam (Amharic: ሕዳሴ ግድብ, romanized: Hidāsē Gidib, Oromo: Hidha Hidāsē), is a gravity dam on the Blue Nile River in Ethiopia under construction since 2011. The dam is in the Benishangul-Gumuz Region of Ethiopia, about 45 km (28 mi) east of the border with Sudan.[7][8]

| Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam | |

|---|---|

The main dam after first filling | |

Location of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in Ethiopia | |

| Official name |

|

| Country | Ethiopia |

| Location | Guba, Benishangul-Gumuz Region |

| Coordinates | 11°12′55″N 35°05′35″E |

| Purpose | Power |

| Status | Under construction |

| Construction began | 2 April 2011 |

| Opening date | 21 July 2020[1] |

| Construction cost | US$5 billion |

| Owner(s) | Ethiopian Electric Power |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Gravity, roller-compacted concrete |

| Impounds | Blue Nile River |

| Height | 145 m (476 ft)[2] |

| Length | 1,780 m (5,840 ft) |

| Elevation at crest | 655 m (2,149 ft) |

| Dam volume | 10,200,000 m3 (13,300,000 cu yd) |

| Spillways | 1 gated, 2 ungated |

| Spillway type | 6 sector gates for the gated spillway |

| Spillway capacity | 14,700 m3/s (520,000 cu ft/s) for the gated spillway |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Millennium Reservoir |

| Total capacity | 74×109 m3 (60,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Active capacity | 59.2×109 m3 (48,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Inactive capacity | 14.8×109 m3 (12,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Catchment area | 172,250 km2 (66,510 sq mi) |

| Surface area | 1,874 km2 (724 sq mi) |

| Maximum length | 246 km (153 mi) |

| Maximum water depth | 140 m (460 ft) |

| Normal elevation | 640 m (2,100 ft) |

| Power Station | |

| Operator(s) | Ethiopian Electric Power |

| Commission date | 2022–?[3] |

| Type | Conventional |

| Turbines |

|

| Installed capacity | |

| Capacity factor | 28.6% |

| Annual generation | 15,76 GWh (est., planned)[5] |

| Website www | |

The primary purpose of the dam is electricity production to relieve Ethiopia's acute energy shortage and for electricity export to neighbouring countries. With a planned installed capacity of 5.15 gigawatts, the dam will be the largest hydroelectric power plant in Africa when completed,[9] as well as among the 20 largest in the world.[10][11][12]

First phase of filling the reservoir began in July 2020 and in August 2020 water level increased to 540 meters (40 meters higher than the bottom of the river which is at 500 meters above sea level).[1][13] The second phase of filling was completed on 19 July 2021, without any binding agreement with Egypt and Sudan, water level increased to around 575 meters..[14] The third filling was completed on 12 August 2022 to a level of 600 metres (2,000 ft), 25 m (82 ft) higher than the prior year completed second fill. It will take between 4 and 7 years to fill with water,[15] depending on hydrologic conditions during the filling period.[16]

On 20 February 2022, the dam produced electricity for the first time, delivering it to the grid at a rate of 375 MW.[3] A second 375 MW turbine was commissioned in August 2022.[17]

Background

The name that the Blue Nile river takes in Ethiopia ("Abay") is derived from the Ge'ez word for 'great' to imply its being 'the river of rivers'. The word Abay still exists in Ethiopian major languages to refer to anything or anyone considered to be superior.

The eventual site for the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam was identified by the United States Bureau of Reclamation in the course of the Blue Nile survey, which was conducted between 1956 and 1964 during the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie. Due to the coup d'état of 1974 and following 17-year-long Ethiopian Civil War, however, the project failed to progress. The Ethiopian Government surveyed the site in October 2009 and August 2010. In November 2010, a design for the dam was submitted by James Kelston.[18]

On 31 March 2011, a day after the project was made public, a US$4.8 billion contract was awarded without competitive bidding to Italian company Salini Impregilo, and the dam's foundation stone was laid on 2 April 2011 by the Prime Minister Meles Zenawi.[19] A rock-crushing plant was constructed, along with a small air strip for fast transportation.[20] The expectation was for the first two power-generation turbines to become operational after 44 months of construction, or early 2015.[21]

Egypt, located over 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi) downstream of the site, opposes the dam, which it believes will reduce the amount of water available from the Nile.[4] Zenawi argued, based on an unnamed study, that the dam would not reduce water availability downstream and would also regulate water for irrigation.[21] In May 2011, it was announced that Ethiopia would share blueprints for the dam with Egypt so that the downstream impact could be examined.[22]

The dam was originally called "Project X", and after its contract was announced it was called the Millennium Dam.[23] On 15 April 2011, the Council of Ministers renamed it Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.[24] Ethiopia has a potential for about 45 GW of hydropower.[25] The dam is being funded by government bonds and private donations. It was slated for completion in July 2017.[18]

The potential impacts of the dam have been the source of severe regional controversy.[26] The Government of Egypt, a country which depends on the Nile for about 97% of its irrigation and drinking water,[27] has demanded that Ethiopia cease construction on the dam as a precondition to negotiations, has sought regional support for its position, and some political leaders have discussed methods to sabotage it.[28] Egypt has planned a diplomatic initiative to undermine support for the dam in the region as well as in other countries supporting the project such as China and Italy.[29] However, other nations in the Nile Basin Initiative have expressed support for the dam, including Sudan, the only other nation downstream of the Blue Nile, although Sudan's position towards the dam has varied over time.[30] In 2014, Sudan accused Egypt of inflaming the situation.[31]

Ethiopia denies that the dam will have a negative impact on downstream water flows and contends that the dam will, in fact, increase water flows to Egypt by reducing evaporation on Lake Nasser.[32] Ethiopia has accused Egypt of being unreasonable; In October 2019, Egypt stated that talks with Sudan and Ethiopia over the operation of a $4 billion hydropower dam that Ethiopia is building on the Nile have reached a deadlock.[33] Beginning in November 2019, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Steven T. Mnuchin began facilitating negotiations between the three countries.[34]

Cost and financing

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is estimated to cost close to 5 billion US dollars, about 7% of the 2016 Ethiopian gross national product.[35] The lack of international financing for projects on the Blue Nile River has persistently been attributed to Egypt's campaign to keep control on the Nile water share.[35] Ethiopia has been forced to finance the GERD with crowd funding through internal fund raising in the form of selling bonds and persuading employees to contribute a portion of their incomes.[36] Contributions are made in the newly official website confirmed by the verified account of the Office of the Prime Minister of Ethiopia[37]

Of the total cost, 1 billion US dollars for turbines and electrical equipment were funded by the Exim Bank of China.[38][39]

Design

The design changed several times between 2011 and 2019. This affected both the electrical parameters and the storage parameters.

Originally, in 2011, the hydropower plant was to receive 15 generating units with 350 MW nameplate capacity each, resulting in a total installed capacity of 5,250 MW with an expected power generation of 15,128 GWh per year.[40] Its planned generation capacity was later increased to 6,000 MW, through 16 generating units with 375 MW nominal capacity each. The expected power generation was estimated at 15,692 GWh per year. In 2017, the design was again changed to add another 450 MW for a total of 6,450 MW, with a planned power generation of 16,153 GWh per year.[41][42] That was achieved by upgrading 14 of the 16 generating units from 375 MW to 400 MW without changing the nominal capacity.[43] According to a senior Ethiopian official, on 17 October 2019,[5] the power generation capacity of the GERD is now 5,150 MW, with 13 turbines (2x 375 MW and 11x 400 MW)[27] down from 16 turbines.

Not only the electrical power parameters changed over time, but also the storage parameters. Originally, in 2011, the dam was planned to be 145 m (476 ft) tall with a volume of 10.1 million m³. The reservoir was planned to have a volume of 66 km3 (54,000,000 acre⋅ft) and a surface area of 1,680 km2 (650 sq mi) at full supply level. The rock-filled saddle dam beside the main dam was planned to have a height of 45 m (148 ft) meters, a length of 4,800 m (15,700 ft) and a volume of 15 million m³.[18][44]

In 2013, an Independent Panel of Experts (IPoE) assessed the dam and its technological parameters. At that time, the reservoir sizes were changed already. The size of the reservoir at full supply level went up to 1,874 km2 (724 sq mi), an increase of 194 km2 (75 sq mi). The storage volume at full supply level had increased to 74 km3 (60,000,000 acre⋅ft), an increase of 7 km3 (1.7 cu mi).[45] These numbers did not change after 2013. The storage volume of 74 km3 (60,000,000 acre⋅ft) is representing nearly entire 84 km3 (68,000,000 acre⋅ft) annual flow of Nile.[27]

After the IPoE made its recommendations, in 2013, the dam parameters were changed to account for higher flow volumes in case of extreme floods: a main dam height of 155 m (509 ft), an increase of 10 m (33 ft), with a length of 1,780 m (5,840 ft) (no change) and a dam volume of 10.2 million cubic metres (360×106 cu ft), an increase of 100,000 m3 (3,500,000 cu ft). The outlet parameters did not change, only the crest of the main dam was raised. The rock saddle dam went up to a height of 50 m (160 ft), an increase of 5 metres (16 ft), with a length of 5,200 m (17,100 ft), an increase of 400 metres (1,300 ft). The volume of the rock saddle dam increased to 16.5 million cubic metres (580×106 cu ft), an increase of 1.5 million cubic metres (53×106 cu ft).[45][46]

The design parameters as of August 2017 are as follows, given the changes as outlined above:

Two dams

The zero level of the main dam, the ground level, will be at a height of about 500 m (1,600 ft) above sea level, corresponding roughly to the level of the river bed of the Blue Nile. Counting from the ground level, the main gravity dam will be 145 m (476 ft) tall, 1,780 m (5,840 ft) long and composed of roller-compacted concrete.[2][13] The crest of the dam will be at a height of 655 m (2,149 ft) above sea level. The outlets of the two powerhouses are below the ground level, the total height of the dam will, therefore, be slightly higher than that of the given height of the dam. In some publications, the main contractor constructing the dam puts forward a number of 170 m (560 ft) for the dam height, which might account for the additional depth of the dam below ground level, which would mean 15 m (49 ft) of excavations from the basement before filling the reservoir. The structural volume of the dam will be 10,200,000 m3 (13,300,000 cu yd). The main dam will be 40 km (25 mi) from the border with Sudan.

Supporting the main dam and reservoir will be a curved and 4.9 km (3 mi) long and 50 m (164 ft) high rock-fill saddle dam.[13] The ground level of the saddle dam is at an elevation of about 600 m (2,000 ft) above sea level. The surface of the saddle dam has a bituminous finish, to keep the interior of the dam dry. The saddle dam will be just 3.3–3.5 km (2–2 mi) away from the border with Sudan, it is much closer to the border than the main dam.

The reservoir behind both dams will have a storage capacity of 74 km3 (60,000,000 acre⋅ft) and a surface area of 1,874 km2 (724 sq mi) when at full supply level of 640 m (2,100 ft) above sea level . The full supply level is therefore 140 m (460 ft) above the ground level of the main dam. Hydropower generation can happen between reservoir levels of 590 m (1,940 ft), the so-called minimum operating level, and 640 m (2,100 ft), the full supply level. The live storage volume, usable for power generation between both levels is then 59.2 km3 (48,000,000 acre⋅ft). The first 90 m (300 ft) of the height of the dam will be a dead height for the reservoir, leading to a dead storage volume of the reservoir of 14.8 km3 (12,000,000 acre⋅ft).[45]

Three spillways

The dams will have three spillways. All using approximately 18,000 cubic meters of concrete. These spillways together are designed for a flood of up to 38,500 m3/s (1,360,000 cu ft/s), an event not considered to happen at all, as this discharge volume is the so-called 'Probable Maximum Flood'. All waters from the three spillways are designed to discharge into the Blue Nile before the river enters Sudanese territory.

The main and gated spillway is located to the left of the main dam and will be controlled by six floodgates and have a design discharge of 14,700 m3/s (520,000 cu ft/s) in total. The spillway will be 84 m (276 ft) wide at the outflow gates. The base level of the spillway will be at 624.9 m (2,050 ft), well below the full supply level.

An ungated spillway, the auxiliary spillway, sits at the center of the main dam with an open width of about 205 m (673 ft). This spillway has a base-level at 640 m (2,100 ft), which is exactly the full supply level of the reservoir. The dam crest is 15 m (49 ft) higher to the left and to the right of the spillway. This ungated spillway is only expected to be used, if the reservoir is both full and the flow exceeds 14,700 m3/s (520,000 cu ft/s), a flow value, that is expected to be exceeded once every ten years.

A third spillway, an emergency spillway, is located to the right of the curved saddle dam, with a base level at 642 m (2,106 ft). This emergency spillway has an open space of about 1,200 m (3,900 ft) along its rim. This third spillway will carry water only if the conditions for a flood of more than around 30,000 m3/s (1,100,000 cu ft/s) are given, corresponding to a flood to occur only once every 10,000 years.

Power generation and distribution

Flanking either side of the auxiliary ungated spillway at the center of the dam will be two power houses, that will be equipped with 2 x 375 MW Francis turbine-generators and 11 x 400 MW turbines.[27] The total installed capacity with all turbine-generators will be 5,150 MW. The average annual flow of the Blue Nile being available for power generation is expected to be 1,547 m3/s (54,600 cu ft/s),[45] which gives rise to an annual expectation for power generation of 16,153 GWh, corresponding to a plant load factor (or capacity factor) of 28.6%.

The Francis turbines inside the power houses are installed in a vertical manner, raising 7 m (23 ft) above the ground level. For the foreseen operation between the minimum operating level and the full supply level, the water head available to the turbines will be 83–133 m (272–436 ft) high. A switching station will be located close to the main dam, where the generated power will be delivered to the national grid. Four 500 kV main power transmission lines were completed in August 2017, all going to Holeta and then with several 400 kV lines to the metropolitan area of Addis Ababa.[47] Two 400 kV lines run from the dam to the Beles Hydroelectric Power Plant. Also planned are 500 kV high-voltage direct current lines.

Early power generation

Two non-upgraded turbine-generators with 375 MW were first to go into operation with 750 MW delivered to the national power grid, while the first turbine was commissioned in February 2022[3] and the second one in August 2022.[17] The two units sit within the 10 unit powerhouse to the right side of the dam at the auxiliary spillway. They are fed by two special intakes within the dam structure that are located at a height of 540 m (1,770 ft) above sea level. That power generation started at a water level of 560 m (1,840 ft), 30 m (98 ft) below the minimum operating level of the other 11 turbine-generators. At that level, the reservoir has been filled with roughly 5.5 km3 (1.3 cu mi) of water, which corresponds to roughly 11% of the annual inflow of 48.8 km3 (11.7 cu mi). During the rainy season, this is expected to happen within days to weeks. The first stage filling of the reservoir for early generation was completed on 20 July 2020.[48][49]

Siltation, evaporation

Two "bottom" outlets at 542 m (1,778 ft) above sea level or 42 m (138 ft) above the local river bed level are available for delivering water to Sudan and Egypt under special circumstances, in particular for irrigation purposes downstream, if the level of the reservoir falls below the minimum operating level of 590 m (1,940 ft) but also during the initial filling process of the reservoir.

The space below the "bottom" outlets is the primary buffer space for alluvium through siltation and sedimentation. For the Roseires Reservoir just downstream from the GERD site, the average siltation and sedimentation volume (without GERD in place) amounts to around 0.035 km3 (28,000 acre⋅ft) per year. Due to the large size of the GERD reservoir, the siltation and sedimentation volume is expected to be much higher in this case, 0.21 km3 (170,000 acre⋅ft) per annum.[45][50] The GERD reservoir will foreseeably take away the siltation threat from the Roseires reservoir almost entirely.

The base of the GERD dam is at around 500 m (1,600 ft) above sea level. Water flowing out of the dam will be released into the Blue Nile again which will flow for only around 30 km (19 mi), before joining the Roseires reservoir, which – if at full supply level – will be at 490 m (1,610 ft) above sea level. There is only a 10 m (33 ft) elevation difference between both projects. The two reservoirs and accompanying hydropower projects could – if coordinated properly across the border between Ethiopia and Sudan – become a cascaded system for more efficient hydropower generation and better irrigation (in Sudan in particular). Water from the 140 m (460 ft) column of the water storage of the GERD reservoir could be diverted through tunnels to facilitate new irrigation schemes in Sudan close to the border with South Sudan. In Ethiopia itself, no irrigation schemes are planned due to the proximity of the dam to the downstream border with Sudan.

Evaporation of water from the reservoir is expected to be at 3% of the annual inflow volume of 48.8 km3 (11.7 cu mi), which corresponds to an average volume lost through evaporation of around 1.5 km3 (0.36 cu mi) annually.[51] This was considered negligible by the IPoE.[45] For comparison, Lake Nasser in Egypt loses between 10–16 km3 (2.4–3.8 cu mi) annually through evaporation.[52]

Construction

The main contractor is the Italian company Webuild (formerly Salini Impregilo), which also served as primary contractor for the Gilgel Gibe II, Gilgel Gibe III and Tana Beles dams. Simegnew Bekele was the project manager of GERD from the start of construction in 2011 up to his death on 26 July 2018. In October same year he was replaced by Kifle Horo. The dam is expected to require 10 million cubic meters of concrete. The government has pledged to use only domestically produced concrete. In March 2012, Salini awarded the Italian firm Tratos Cavi SPA a contract to supply low- and high-voltage cable for the dam.[46][53] Alstom will provide the eight 375 MW Francis turbines for the project's first phase, at a cost of €250 million.[54] As of April 2013, nearly 32 per cent of the project was complete. Site excavation and some concrete placement was underway. One concrete batch plant has been completed with another under construction.[55] Diversion of the Blue Nile was completed on 28 May 2013 and marked by a ceremony the same day.[56]

In October 2019, the work was approximately 70% complete.[57] As of March 2020, the steelworks reached 35% complete, civil works are 87% complete while electro-mechanical works are 17% complete, to attain in total 71% construction complete according to Belachew Kasa, Project Deputy Director.[58]

On 26 June 2020, Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia agreed to delay filling the reservoir for a few weeks.[59]

On 21 July 2020, Ethiopian prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, announced that the first phase of filling the reservoir had been completed.[60] The early filling was attributed to heavy rains. In his statement, Abiy stated that "We have successfully completed the first dam filling without bothering and hurting anyone else. Now the dam is overflowing downstream".[60] The target for the first year filling was 4.9 cubic kilometres, while the dam has capacity to hold 74 cubic kilometres when completed.[61]

The first phase of filling the reservoir began in July 2020, to a maximum depth of 70 metres (230 ft) utilising a temporary sill. Further construction work is necessary before the reservoir can be filled to a level for electricity generation.[1][13]

The second phase of filling of the GERD reservoir was completed on 19 July 2021[62] with estimates of reaching the level of 573 metres (1,880 ft) (a.m.s.l) and retaining no more than 4.5 km3 (1.1 cu mi) at this stage.[63][64]

In February 2021, Ethiopian Minister of Water and Irrigation, Seleshi Bekele, mentioned that the engineering work in constructing the dam reached 91%, while the total construction rate was 78.3%.[65] In May 2021, Minister of Water and Irrigation Seleshi Bekele mentioned that 80% of dam construction was complete.[66]

Controversies

Engineering questions

In 2012, the International Panel of Experts was formed with experts from Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and other independent entities to discuss mainly engineering and partially impact related questions. This panel concluded at a number of engineering modifications, that were proposed to Ethiopia and the main contractor constructing the dam. One of the two main engineering questions, dealing with the size of flood events and the constructive response against them, was later addressed by the contractor. The emergency spillway located near the rock saddle dam saw an increase of the rim length from 300 m to 1,200 m to account even for the largest possible flood of the river.

The second main recommendation of the panel however found no immediate resolution. This second recommendation dealt with the structural integrity of the dam in context with the underlying rock basement as to avoid the danger of a sliding dam due to an unstable basement. It was argued by the panel, that the original structural investigations considered only a generic rock mass without taking special conditions like faults and sliding planes in the rock basement (gneiss) into account. The panel noted, that there was indeed an exposed sliding plane in the rock basement, this plane potentially allowing a sliding process downstream. The panel didn't argue that a catastrophic dam failure with a release of dozens of cubic kilometres of water would be possible, probable or even likely, but the panel argued, that the given safety factor to avoid such a catastrophic failure might be non-optimal in the case of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.[45] It was later revealed that the underlying basement of the dam was completely different from all expectations and did not fit the geological studies as the needed excavation works exposed the underlying gneiss. The engineering works then had to be adjusted, with digging and excavating deeper than originally planned , which took extra time and capacity and also required more concrete.[67]

Alleged over-sizing

Originally, in 2011, the hydropower plant was to receive 15 generating units with 350 MW nameplate capacity each, resulting in a total installed capacity of 5,250 MW with an expected power generation of 15,128 GWh per annum.[40] The capacity factor of the planned hydropower plant – the expected electricity production divided by the potential production if the power plant was utilised permanently at full capacity – was only 32.9% compared to 45–60% for other, smaller hydropower plants in Ethiopia. Critics concluded that a smaller dam would have been more cost-effective.[40]

Soon after, in 2012, the hydropower plant was upgraded to receive 16 generating units with 375 MW nameplate capacity each, increasing the total installed capacity to 6,000 MW, with the expected power generation going up only slightly to 15,692 GWh per annum. Consequently, the capacity factor shrank to 29.9%. According to Asfaw Beyene, a professor of mechanical engineering at San Diego State University in California, the dam and its hydropower plant are massively oversized: "GERD’s available power output, based on the average of river flow throughout the year and the dam height, is about 2,000 megawatts, not 6,000. There is little doubt that the system has been designed for a peak flow rate that only happens during the two to three months of the rainy season. Targeting near peak or peak flow rate makes no economic sense."[68][69]

In 2017, the total installed capacity was moved to 6,450 MW, without changing the number and nameplate capacity of the generating units (which then remained at 6,000 MW in total). This was thought to arrive from enhancements made to the generators.[10] The expected power generation per annum went up to 16,153 GWh,[41] the capacity factor shrank again and reached 28.6%. This time nobody publicly voiced concern. Such optimisation of the Francis turbines used at the dam site is indeed possible and is usually done by the provider of the turbines taking into account site-specific conditions.

Considering the critics voiced about the alleged over-sizing of the possible power output, now of 6,450 MW. Ethiopia is relying heavily on hydropower, but the country is often affected by droughts (see e.g. 2011 East Africa drought). The water reservoirs used for power generation in Ethiopia have a limited size. For example, the Gilgel Gibe I reservoir, that feeds both the Gilgel Gibe I powerplant and the Gilgel Gibe II Power Station, has a capacity of 0.7 km3. In times of drought, there is no water left to generate electrical power. This heavily affected Ethiopia in the drought years 2015/16 and it was only the Gilgel Gibe III powerplant, that in 2016 just started to run in trial service on a 14 km3 well-filled reservoir, that saved the economy of Ethiopia.[67] The GERD reservoir, once it has been filled, has a total water volume of 74 km3, 3 times the volume of Ethiopia's largest lake, Lake Tana. Filling it takes 5–15 years and even by using all generating units at maximum capacity will not drain it within a few months. The installed power of 6.450 MW in combination with the size of the reservoir will help to manage the side effects of the next severe drought, when other hydropower plants have to stop their operations.

Security around dam

In recent years due to the threat of a possible airstrike on the dam, the Ethiopian government has sought and bought several air defence systems some from Russia, including the Pantsir-S1 air defence system, and also Israeli air defences, including the SPYDER-MR medium-range air defence system which was installed in the dam. Egypt has sought to block a sale between Israel and Ethiopia but has failed due to the installations of the air defences on the dam. Israel was seen denying the request of Egypt by not answering their request.[70][71][72][73][74]

Benefits

A major benefit of the dam will be hydropower production. All the energy generated by GERD will be going into the national grid of Ethiopia to fully support the development of the whole country, both in rural and urban areas. The role of GERD will be to act as a stabilising backbone of the Ethiopian national grid. There will be exports, but only if there is a total surplus of energy generated in Ethiopia. This is mainly expected to happen during rainy seasons, when there is plenty of water for hydropower generation.[67]

The eventual surplus electricity of GERD which does not fit the demand inside Ethiopia, is then to be sold and exported to neighbouring countries including Sudan and possibly Egypt, but also Djibouti.[75] Exporting the electricity from the dam would require the construction of massive transmission lines to major consumption centers such as Sudan's capital Khartoum, located more than 400 km away from the dam. These export sales would come on top of electricity that is expected to be sold from other large hydropower plants. Powerplants that have been readied or are under construction in Ethiopia, such as Gilgel Gibe III or Koysha, whose exports (if given surplus energy) will mainly be going to Kenya through a 500 kV HVDC line.

The volume of the reservoir will be two to three times that of Lake Tana. Up to 7,000 tonnes of fish are expected to be harvested annually. The reservoir may become a tourist destination.[76]

Sudan expects a reduce in floods thanks to the dam, but this has not been observed in reality yet.[77][78]

Environmental and social impacts

The NGO International Rivers has commissioned a local researcher to make a field visit because so little environmental impact information is publicly available.[79]

Public consultation about dams in Ethiopia is affected by the political climate in the country. International Rivers reports that "conversations with civil society groups in Ethiopia indicate that questioning the government's energy sector plans is highly risky, and there are legitimate concerns of government persecution. Because of this political climate, no groups are actively pursuing the issues surrounding hydro-power dams, nor publicly raising concerns about the risks in this situation, extremely limited and inadequate public consultation has been organised" during the implementation of major dams.[80] In June 2011, Ethiopian journalist Reeyot Alemu was imprisoned after she raised questions about the proposed Grand Millennium Dam. Staff of International Rivers have received death threats. Former prime minister Meles Zenawi called opponents of the project "hydropower extremists" and "bordering on the criminal" at a conference of the International Hydropower Association (IHA) in Addis Ababa in April 2011. At the conference, the Ethiopian state power utility was embraced as a "Sustainability Partner" by the IHA.[81]

Impact on Ethiopia

Since the Blue Nile is a highly seasonal river, the dam would reduce flooding downstream of the dam, including on the 15 km stretch within Ethiopia. On the one hand, the reduction of flooding is beneficial since it protects settlements from flood damage. On the other hand, it can be harmful if flood recession agriculture is practised in the river valley downstream of the dam since it deprives fields from being watered. However, the next water regulating dam in Sudan, the Roseires Dam, sits only a few dozens of kilometres downstream. The dam could also serve as a bridge across the Blue Nile, complementing a bridge that was under construction in 2009 further upstream.[82] An independent assessment estimated that at least 5,110 people will be resettled from the reservoir and downstream area, and the dam is expected to lead to a significant change in the fish ecology.[79] According to an independent researcher who conducted research in the area, 20,000 people are being relocated. According to the same source, "a solid plan (is) in place for the relocated people" and those who have already been resettled "were given more than they expected in compensation". Locals have never seen a dam before and "are not completely sure what a dam actually is", despite community meetings in which affected people were informed about the impacts of the dam on their livelihoods. Except for a few older people, almost all locals interviewed "expressed hope that the project brings something of benefit to them" in terms of education and health services or electricity supply based on the information available to them. At least some of the new communities for those relocated will be downstream of the dam. The area around the reservoir will consist of a 5 km buffer zone for malaria control that will not be available for settlement. In at least some upstream areas erosion control measures will be undertaken in order to reduce siltation of the reservoir.[83]

Impact on Sudan and Egypt

| |

| Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam |

The precise impact of the dam on the downstream countries is not known. Egypt fears a temporary reduction of water availability due to the filling of the reservoir and a permanent reduction because of evaporation from the reservoir. Studies indicate that the primary factors which will govern the impacts during the reservoir filling phase include the initial reservoir elevation of the Aswan High Dam, the rainfall that occurs during the filling period and the negotiated arrangement between the three countries. These studies also show that only through close and continuous coordination, the risks of negative impacts can be minimised or eliminated.[16] The reservoir volume (74 cubic kilometres) is about 1.5 times the average annual flow (49 cubic kilometres) of the Blue Nile at the Egypt–Sudan border. This loss to downstream countries could be spread over several years if the countries reach an agreement. Depending on the initial storage in the Aswan High Dam and this filling schedule of the GERD, flows into Egypt could be temporarily reduced,[51] which may affect the livelihood of two million farmers during the period of filling the reservoir. Allegedly, it would also "affect Egypt's electricity supply by 25 to 40 percent, while the dam is being built".[84] However, hydropower accounts for less than 12 per cent of total electricity production in Egypt in 2010 (14 out of 121 billion kWh),[85] so that a temporary reduction of 25 per cent in hydropower production translates into an overall temporary reduction in Egyptian electricity production of less than 3 per cent. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam could also lead to a permanent lowering of the water level in Lake Nasser if floods are stored instead in Ethiopia. This would reduce the current evaporation of more than 10 cubic kilometres per year, but it would also reduce the ability of the Aswan High Dam to produce hydropower to the tune of a 100 MW loss of generating capacity for a 3 m reduction of the water level. However, the increased storage in Ethiopia can provide a greater buffer to shortages in Sudan and Egypt during years of future drought, if the countries can reach a compromise.[64]

The dam will retain silt. It will thus increase the useful lifetime of dams in Sudan – such as the Roseires Dam, the Sennar Dam and the Merowe Dam – and of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt. The beneficial and harmful effects of flood control would affect the Sudanese portion of the Blue Nile, just as it would affect the Ethiopian part of the Blue Nile valley downstream of the dam.[86] Specifically, the GERD would reduce seasonal flooding of the plains surrounding the reservoir of the Roseires Dam located at Ad-Damazin, just as the Tekeze Dam, by retaining a reservoir in the deep gorges of the northern Ethiopian Highlands, had reduced flooding at Sudan's Khashm el-Girba Dam.[87]

The reservoir, located in the temperate Ethiopian Highlands and up to 140 m deep, will experience considerably less evaporation than downstream reservoirs such as Lake Nasser in Egypt, which loses 12% of its water flow due to evaporation as the water sits in the lake for 10 months. Through the controlled release of water from the reservoir to downstream, this could facilitate an increase of up to 5% in Egypt's water supply, and presumably that of Sudan as well.[88]

Reactions: cooperation and condemnation

Egypt has serious concerns about the project;[90] therefore it requested to be granted inspection allowance on the design and the studies of the dam, in order to allay its fears, but Ethiopia has denied the request unless Egypt relinquishes its veto on water allocation.[91] After a meeting between the Ministers of Water of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia in March 2012, Sudan's President Bashir said that he supported the building of the dam.[92]

A Nile treaty signed by the upper riparian states in 2010, the Cooperative Framework Agreement,[93] has not been signed by either Egypt or Sudan, as they claim it violates the 1959 treaty,[94] in which Sudan and Egypt give themselves exclusive rights to all of the Nile's waters.[95] The Nile Basin Initiative provides a framework for dialogue among all Nile riparian countries.[87]

Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan established an International Panel of Experts to review and assess the study reports of the dam. The panel consists of 10 members; 6 from the three countries and 4 international in the fields of water resources and hydrologic modelling, dam engineering, socioeconomic and environmental.[86] The panel held its fourth meeting in Addis Ababa in November 2012. It reviewed documents about the environmental impact of the dam and visited the dam site.[96] The panel submitted its preliminary report to the respective governments at the end of May 2013. Although the full report has not been made public, and will not be until it is reviewed by the governments, Egypt and Ethiopia both released details. The Ethiopian government stated that, according to the report, "the design of the dam is based on international standards and principles" without naming those standards and principles. It also said that the dam "offers high benefit for all the three countries and would not cause significant harm on both the lower riparian countries".[97] According to Egyptian government, however, the report "recommended changing and amending the dimensions and the size of the dam".[98] As of mid-July 2022 the three-way negotiations were not held for more that a year.[99]

On 3 June 2013, while discussing the International Panel of Experts report with President Mohammad Morsi, Egyptian political leaders suggested methods to destroy the dam, including support for anti-government rebels.[100][101] Unbeknownst to those at the meeting, the discussion was televised live.[28] Ethiopia requested that the Egyptian Ambassador explain the meeting.[102] Morsi's top aide apologised for the "unintended embarrassment" and his cabinet released a statement promoting "good neighbourliness, mutual respect and the pursuit of joint interests without either party harming the other." An aide to the Ethiopian Prime Minister stated that Egypt is "...entitled to daydreaming" and cited Egypt's past of trying to destabilise Ethiopia.[103] Morsi reportedly believes that it is better to engage Ethiopia rather than attempt to force them.[28] However, on 10 June 2013, he said that "all options are open" because "Egypt's water security cannot be violated at all," clarifying that he was "not calling for war," but that he would not allow Egypt's water supply to be endangered.[104]

In January 2014, Egypt left negotiations over the dam, citing Ethiopian intransigence.[32] Ethiopia countered that Egypt had set an immediate halt on construction and an increase of its share to 90% as the preconditions, which were deemed wholly unreasonable. Egypt has since launched a diplomatic offensive to undermine support for the dam, sending its Foreign Minister, Nabil Fahmi to Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to garner support. Egyptian media outlets declared the visits productive and that the leaders of those nations had expressed "understanding" and "support" of Egypt's position.[105] Sudanese Foreign Minister Ali Karti criticised Egypt for "inflaming the situation" through its statements on the dam, and that it was considering the interests of both sides. Al-Masry Al-Youm declared that Sudan had "proclaimed its neutrality".[31][106] The campaign is intensive and wide-reaching; in March 2014, for the first time, only Uganda, Kenya, Sudan and Tanzania were invited by Egypt to participate in the Nile Hockey Tournament.[107] Foreign Minister Fahmi and Water Resources Minister Muhammad Abdul Muttalib planned visits to Italy and Norway to express their concerns and try to compel them to pull their support for the GERD.[87]

.jpg.webp)

In April 2014, Ethiopia's Prime Minister invited Egypt and Sudan to another round of talks over the dam and Nabil Fahmi stated in May 2014 that Egypt was still open to negotiations.[108] Following an August 2014 Tripartite Ministerial-level meeting, the three nations agreed to set up a Tripartite National Committee (TNC) meeting over the dam. The first TNC meeting occurred from 20 to 22 September 2014 in Ethiopia.[109]

In October 2019, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed warned that "no force can stop Ethiopia from building a dam. If there is need to go to war, we could get millions readied."[110]

Beginning in November 2019, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin facilitated negotiations between the governments of Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan with respect to the filling and the operation of the dam.[34] Ethiopia proposed filling the reservoir with a release of 35 cubic kilometres of water per year, resulting in the complete filling of the reservoir in five years. Egypt countered that this would be too little, and demanded a larger amount of water to be released each year, asking for 40 cubic kilometres of water to be released and for the reservoir to be filled within seven years.[111] In February 2020, Mnuchin said in a statement: "We appreciate the readiness of the government of Egypt to sign the agreement and its initialing of the agreement to evidence its commitment," adding "consistent with the principles set out in the DOP, and in particular the principles of not causing significant harm to downstream countries, final testing and filling should not take place without an agreement."[112][113] Ethiopian Foreign Minister Gedu Andargachew said Mnuchin's advice to Ethiopia was "ill-advised".[114]

In February 2020, the U.S. Treasury Department stated that "final testing and filling should not take place without an agreement." after Ethiopia skipped US talks with Egypt over the dam dispute. Ethiopians online expressed anger using the hashtag #itismydam over what they claim was the US and the World Bank's siding with Egypt contrary to the co-observer role initially promised. The online campaign coincided with Ethiopia's annual public holiday celebrating the 1896 Ethiopian victory at the Battle of Adwa, a decisive victory that successfully thwarted the 1896 Italian colonial campaign. Ethiopia has stated that "it will not be pressured on Nile River".

In July 2020, Ethiopian Foreign Minister Gedu Andargachew tweeted: "the river became a lake... the Nile is ours."[1] In the same month, talks between water ministers from three involved countries resumed under African Union supervision.[115]

In September 2020, the United States suspended part of its economic assistance to Ethiopia due to the lack of sufficient progress in negotiations with Sudan and Egypt over the construction of the dam.[116] On 24 October 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump stated on a public phone call to Sudan's Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that "it's a very dangerous situation because Egypt is not going to be able to live that way... And I said it and I say it loud and clear - they'll blow up that dam. And they have to do something." Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed responded that "Ethiopia will not cave in to aggression of any kind" and that threats were "misguided, unproductive and clear violations of international law."[117]

In April 2021, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi warned: "I am telling our brothers in Ethiopia, let’s not reach the point where you touch a drop of Egypt’s water, because all options are open."[118] The dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia over the dam escalated in 2021.[119][120][121] An advisor to the Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan spoke of a water war "that would be more horrible than one could imagine".[122]

On 8 July 2021, the U.N. Security Council held a session to discuss the dispute over the dam filling.[123]

During Joe Biden's July 2022 meeting in the Middle East, he met with Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and restated American support for Egypt's "water security" and "forging a diplomatic resolution that would achieve the interests of all parties and contribute to a more peaceful and prosperous region."[124]

During the summer of 2022, U.S. envoy Mike Hammer visited both Egypt and later Ethiopia to build relations and discuss the Ethiopian dam.[125][126]

In August 2022, the United Arab Emirates (which has good relations with both Ethiopia and Egypt) has stated that it wants the three nations to hold meetings once again.[127][128]

See also

- Water politics

- Renewable energy in Ethiopia

- Dams and reservoirs in Ethiopia

- List of power stations in Ethiopia

- Water politics in the Nile Basin

- Foreign relations of Ethiopia

- Jonglei Canal

- Genale Dawa III Hydroelectric Power Station

References

- "Nile dam row: Egypt fumes as Ethiopia celebrates". BBC News. 30 July 2020.

- "About The Dam". GERD Coordination Office. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "Ethiopia starts generating power from River Nile dam". BBC News. 20 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- "Egypt Stays Opposed to Ethiopia's Grand Millennium Dam Project". EZega. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Power Generation Capacity of GERD Slashed to 5150MW – Ethiopian Minister". ezega.com. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- "Hidha Haaromsaa Guddicha Itoophiyaa 'Adwaa Lammaffaa' lammiilee Itoophiyaa tokkoomse". BBC News Afaan Oromoo (in Oromo). Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Ethiopia's biggest dam to help neighbours solve power problem". News One. 17 April 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- Roussi, Antoaneta (10 October 2019). "Nations Clash over Giant Nile Dam". Nature. 574 (7777): 159–60. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02987-6. PMID 31595068. S2CID 203929162.

- The bitter dispute over Africa’s largest dam: Egypt, Ethiopia (the main contibuter of river Nile i.e more than 86%) and Sudan are struggling to share water The Economist, 4 July 2020

- "Ethiopia: GERD Increases Generation Capacity". allAfrica. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "Salini will build the biggest dam in Africa". Salini Construttori. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- Ahmed, A. T.; Elsanabary, M. H. (13 March 2015). "Hydrological and Environmental Impacts of Grand Renaissance Dam on the Nile River" (PDF). Sharm El Sheikh– Egypt: Eighteenth International Water Technology Conference (CNKI). Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Ethiopia: First stage of the filling of the reservoir of the Grand Renaissance Dam". Tractebel Engie. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "People's Dam Impounded, GERD-Locked Diplomacy, and Egypt's Red Line for a Non-Deferent Ethiopia". Geopolitics Press. 22 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Gets Set to Open. Ethiopian Yearbook of International Law 2019. 13 February 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-55912-0_12. ISBN 9783030559120. S2CID 232321212. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Wheeler, Kevin G.; Basheer, Mohammed; Mekonnen, Zelalem T.; Eltoum, Sami O.; Mersha, Azeb; Abdo, Gamal M.; Zagona, Edith A.; Hall, Jim W.; Dadson, Simon J. (6 June 2016). "Cooperative filling approaches for the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Water International. 41 (4): 611–634. doi:10.1080/02508060.2016.1177698.

- "Ethiopia announces that second turbine in GERD is in operation". Africanews. 11 August 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Project, Benishangul-Gumuz, Ethiopia". Water Technology. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Ethiopia Launched Grand Millennium Dam Project, the Biggest in Africa". Ethiopian News. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- Belete, Pawlos. "Great Millennium Dam moves Ethiopia". Capital Ethiopia. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Meles Launches Millennium Dam Construction on Nile River". New Business Ethiopia. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Egypt approves of Ethiopia's Renaissance Dam in principle". Ethiopia News. 16 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- "A Nation Rallies Behind a Cause". Grand Millennium Dam. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- "Council of Ministers Approves Regulation Establishing Council on Grand Dam". Ethiopian Government. 16 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- Thomas Land (5 February 2013). "Egypt & Sudan outraged by Ethiopia's Blue Nile Dam". Hydro World. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- Walsh, Decian; Sengupta, Somini; Boushnak, Laura (9 February 2020). "For Thousands of Years, Egypt Controlled the Nile. A New Dam Threatens That". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "First power production at the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Hydropower & Dams. 29 (2): 3.

- "Ethiopia official labels Egyptian attack proposals over new Nile River dam 'day dreaming'". The Washington Post. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Egypt plans dam-busting diplomatic offensive against Ethiopia". United Press International. 27 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Marks, Simon; Gebre, Samuel (16 July 2021). "Why Ethiopia's Mega-Dam Has Its Neighbors Fuming". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

During Omar al-Bashir's rule, Sudan accepted Ethiopia's assurances that the dam would help control flooding and that Sudan would benefit from the power generated. Since al-Bashir was toppled in 2019, Sudan has aligned itself with Egypt, saying the Nile is joint property and an agreement must be reached before the reservoir can be filled.

- "Sudan Foreign Minister Criticises Egypt Over Ethiopian Dam Dispute". Sudan Tribune. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Hussein, Hassen (6 February 2014). "Egypt and Ethiopia spar over the Nile". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Egypt says talks over Ethiopia's Nile dam deadlocked, calls for mediation". Reuters. 5 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "Joint Statement of Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, the United States And the World Bank | U.S. Department of the Treasury". home.treasury.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Wossenu Abtew; Shimelis Behailu Dessu (2019). "Financing the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Springer International Publishing.

- "Ethiopia sells 56 mln USD bond to diaspora to finance mega dam". Xinhuanet. 30 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018.

- Office of the Prime Minister of Ethiopia [@PMEthiopia] (24 July 2021). "Ethiopian Electric Power launches [...]" (Tweet). Retrieved 3 November 2022 – via Twitter.

- "Al-Arabiya Arabic| International decision not to finance Ethiopia's dam". Horn Affairs. 24 April 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Mbaku, John Mukum (5 August 2020). "The controversy over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Brookings. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Beyene, Mehari (14 July 2011). "How efficient is The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam?" (PDF). International Rivers. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- "Purpose driven commitment from every corner to realize Ethiopian Renaissance". Ethiopian Herald (ENA). 5 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Ethiopia: GERD Increases Generation Capacity". allAfrica. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "Nuts and bolts of Ethiopian power sector". Reporter Ethiopia. 4 March 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "[Updated] Facts – Grand Ethiopian Renaissance dam". Hornaffairs. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- "International Panel of Experts on Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Project (GERDP) – Final Report" (PDF). International rivers. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- "Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Project". Salini. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "EEP readies 1,400km long high power transmission lines, distribution stations". 25 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Satellite images show Ethiopia dam reservoir swelling, AP News.

- @afp (22 July 2020). "Ethiopia says first year of Nile mega-dam filling 'achieved'" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Sediment Accumulation in Roseires Reservoir" (PDF). IWMI.org. 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- Elsayed, Hamdy; Djordjević, Slobodan; Savić, Dragan A.; Tsoukalas, Ioannis; Makropoulos, Christos (1 November 2020). "The Nile Water-Food-Energy Nexus under Uncertainty: Impacts of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management. 146 (11): 04020085. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0001285. ISSN 1943-5452. S2CID 224865271.

- "Evaporation Reduction from Lake Nasser Using New Environmentally Safe Techniques" (PDF). IWTC. 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- "Tratos wins contract for 6,800 MW Ethiopian project". HydroWorld.com. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Alstom:Alstom to supply hydroelectric equipment for the Grand Renaissance dam in Ethiopia, 7 January 2013

- "Current Project Status". Office of National Council for the Coordination of Public Participation on the Construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- "Ethiopia: Blue Nile Diversion Allows Dam Construction to Continue". allAfrica. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "Egypt, Ethiopia 'agree' to resume talks on massive Nile dam". Ethiopia: Al Jazeera. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Construction of Ethiopia's Grand Renaissance Dam now 71% complete". Construction Review Online. 5 March 2020. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan agree to delay filling dam". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Ethiopia's leader hails 1st filling of massive, disputed dam". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Ethiopia says it has reached first-year target for filling divisive mega-dam". france24.com. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Ethiopia hits second-year target for filling Nile mega-dam". France 24. 19 July 2021.

- "Sudan Renews Warning on Nile Dam, Moves to Avert Water Shortages". Bloomberg.com. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Elsayed, Hamdy; Djordjevic, Slobodan; Savic, Dragan; Tsoukalas, Ioannis; Makropoulos, Christos (3 January 2022). "Water-food-energy nexus for transboundary cooperation in Eastern Africa". Water Supply. 22 (4): 3567–3587. doi:10.2166/ws.2022.001. ISSN 1606-9749. S2CID 245712665.

- "Ethiopia: We built 78% of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam … and will continue filling soon". asumetech.com. 5 February 2021.

- "Ethiopia: 80% of dam construction complete". Middle East Monitor. 20 May 2021.

- "Power Play". Capital Ethiopia. 2 January 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Why is the hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), sized for 6000 MW?". Finfinne Tribune. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- "Ethiopia's Biggest Dam Oversized, Experts Say". International Rivers: An Interview with Asfaw Beyene. 5 September 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- "Ethiopia operating Pantsir-S1 air defence systems". Defence Web. 20 March 2019.

- "Friction With Cairo Over The Israel Air Defense System For Ethiopia's Great Nile Dam". Dinknesh Ethiopia. 15 January 2020.

- Ebatamehi, Sebastiane (23 July 2019). "Egypt Expresses Concerns Over Israeli Ties With Ethiopia". African Exponent.

- "Ethiopia Ready to fight off Egypt missile attacks from Dam". The Low Ethiopian Reports. 6 December 2021.

- Zaher, Hassan (20 July 2019). "Concerns mount in Egypt as Israel boosts ties with Ethiopia". The Arab Weekly.

- "How Ethiopia's huge dam could transform parts of Africa". Reuters. 29 July 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- "The reality of the GERD". Ethiopian Herald (ENA). 26 February 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Reuters (25 August 2021). "Sudan says Ethiopian dam made no impact on floods this year". Reuters. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- "How the controversial Nile dam might fix Sudan's floods". BBC News. 1 November 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Pottinger, Lori (31 January 2013). "Field Visit Report on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". International Rivers. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- International Rivers: What Cost Ethiopia’s Dam Boom? Archived 22 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, February 2008, pp. 13–14. Retrieved 25 April 2011

- Bosshard, Peter (13 July 2011). "Sustainable Hydropower – Ethiopian Style". International Rivers. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Daily Ethiopia:Longest Ever Bridge In Ethiopia Under Construction, 31 December 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2011

- Veilleux, Jennifer (9 July 2013). "another view on the Nile : an interview with Jennifer Veilleux". catherinepfeifer blog. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "Death on the Nile". Al Jazeera. 30 May 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "Egypt Overview". US Energy Information Administration. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "The dam speech". Grand Millennium Dam. 20 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Wheeler, Kevin G.; Jeuland, Marc; Hall, Jim W.; Zagona, Edith; Whittington, Dale (December 2020). "Understanding and managing new risks on the Nile with the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5222. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5222W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19089-x. PMC 7567800. PMID 33067462.

- Salem, Mahmoud (3 June 2013). "Regarding the Dam". Daily News Egypt. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "In Africa, War Over Water Looms As Ethiopia Nears Completion Of Nile River Dam". NPR. 27 February 2018.

- "Video| GERD: A Decade of Futile Negotiations Over Nile Dam Dispute". Daily News Egypt. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Ethiopia won't allow inspection of dam, but ready to negotiate with post-Mubarak Egypt". Almasry Alyoum. 23 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Tesfa-Alem Tekle:Sudan’s Bashir supports Ethiopia’s Nile dam project, Sudan Tribune, 8 March 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013,

- Allouche, Jeremy (2020). "Nationalism, Legitimacy and Hegemony in Transboundary Water Interactions". Water Alternatives. 13:2.

- "Agreement between the Republic of the Sudan and the United Arab Republic for the full utilization of the Nile waters signed at Cairo, 8 November 1959". FAO.

- Abedje, Ashenafi (17 March 2011). "Nile River Countries Consider Cooperative Framework Agreement". Voice of America. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Tesfa-Alem Tekle:Panel pushes study on Ethiopia’s Nile dam amid Egypt crises, Sudan Tribune, 1 December 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013,

- "International Panel of Experts on GERD Releases Its Report". Inside Ethiopia. 1 June 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Ethiopia agrees on recommendations of tripartite committee". Egyptian State Information Service. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013. (link was dead and story could not be found on the ESIS website on 2 July 2013, but a quote can be found at HornAffairs:Egypt: The report modifies renaissance dam's size, dimensions)

- Gomaa, Ahmed (18 July 2022). "As negotiations falter, Ethiopia begins third-stage filling of Nile dam". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Caught on tape, Egyptian lawmakers plot Nile dam sabotage". New York Amsterdam News. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "STRATFOR: Egypt Is Prepared To Bomb All Of Ethiopia's Nile Dams". Business Insider. 13 October 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Ethiopia summons Egypt's ambassador over Nile dam attack proposals". The Washington Post. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Ethiopia: Egypt Attack Proposals 'Day Dreaming'". Ya Libnan. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Egyptian warning over Ethiopia Nile dam". BBC News. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "Fahmy meets Tanzanian president ahead of Congo visit". Daily News Egypt. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Sudan declares neutrality in Renaissance Dam problem, offers mediation between Egypt and Ethiopia". Egypt Independent. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Tanzania Gets Nile Hockey Tourney Invitation". Tanzania Daily News. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Egypt willing to negotiate over Ethiopia's dam: Foreign minister". Ahram Online. 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Ethiopia: The First Meeting of the Tripartite National Committee On the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Concludes". All Africa. 22 September 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Ethiopia's Abiy Ahmed issues warning over Renaissance Dam". Al Jazeera. 22 October 2019.

- Roussi, Antoaneta (10 October 2019). "Nations clash over giant Nile dam". Nature. 574 (7777): 159–160. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02987-6. PMID 31595068. S2CID 203929162.

- "Egypt slams Ethiopia for Renaissance dam remarks". Egypt Today. 1 March 2020.

- "No Deal From US-Brokered Nile Dam Talks". VOA News. 29 February 2020.

- "Ethiopia thrashes US advise on dam filling". Anadolu Agency. 4 March 2020.

- "Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan resume AU-brokered negotiations over Nile dam". Daily News Egypt. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "US suspends aid to Ethiopia over Blue Nile dam dispute". Al Jazeera. 3 September 2020.

- "Trump comment on 'blowing up' Nile Dam angers Ethiopia". BBC News. 24 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "Egypt's el-Sisi warns 'all options open' after dam talks fail". Al Jazeera. 7 April 2021.

- "Sudan threatens legal action if Ethiopia dam filled without deal". Al Jazeera. 23 April 2021.

- "Egypt, Sudan conclude war games amid Ethiopia's dam dispute". Associated Press. 31 May 2021.

- "Egypt and Sudan urge Ethiopia to negotiate seriously over giant dam". Reuters. 9 June 2021.

- "Gerd: Sudan talks tough with Ethiopia over River Nile dam". BBC News. 22 April 2021.

- "U.N. Security Council backs AU bid to broker Ethiopia dam deal". Reuters. 8 July 2021.

- House, The White (16 July 2022). "Joint Statement Following Meeting Between President Biden and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi in Jeddah". The White House. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Egypt, U. S. Mission (24 July 2022). "Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa Mike Hammer's Travel to Egypt, the UAE, and Ethiopia". U.S. Embassy in Egypt. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Egypt, U. S. Mission (27 July 2022). "The United States is Committed to Egypt's Water Security and Advancing a Resolution on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". U.S. Embassy in Egypt. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "UAE calls on Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia to resume talks on GERD 'in good faith'". Egypt Today. 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Nile dam dispute solution 'within reach,' says UAE". Arab News. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.