Melilla

Melilla (US: /məˈliːjə/ mə-LEE-yə, UK: /mɛˈ-/ meh-;[2][3] Spanish: [meˈliʎa]; Tarifit: Mřič [mrɪtʃ];[4] Arabic: مليلية [maˈliːlja]) is an autonomous city of Spain located in north Africa. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of 12.3 km2 (4.7 sq mi). It was part of the Province of Málaga until 14 March 1995, when the Statute of Autonomy of Melilla was passed.

Melilla

Mřič (Tarifit) | |

|---|---|

_Aterrizando_en_Melilla_(16668390111).jpg.webp) Aerial view | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Melilla Location of Melilla | |

| Coordinates: 35°18′N 2°57′W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Government | |

| • Mayor-President | Eduardo de Castro (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.3 km2 (4.7 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 19th |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 86,384 |

| • Rank | 19th |

| • Density | 7,000/km2 (18,000/sq mi) |

| • % of Spain | 0.16% |

| Demonyms | Melillan melillense (es) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | ES-ML |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Statute of Autonomy | 14 March 1995 |

| Parliament | Assembly of Melilla |

| Congress | 1 deputy (of 350) |

| Senate | 2 senators (of 264) |

| Website | www.melilla.es |

| |

Melilla is one of the special member state territories of the European Union. Movements to and from the rest of the EU and Melilla are subject to specific rules, provided for inter alia in the Accession Agreement of Spain to the Schengen Convention.[5]

As of 2019, Melilla had a population of 86,487.[6] The population is chiefly divided between people of Iberian and Riffian extraction.[7] There is also a small number of Sephardic Jews and Sindhi Hindus. Regarding sociolinguistics, Melilla features a diglossia between the official Spanish (strong language) and Tarifit (weak language).[8]

Melilla, like the autonomous city of Ceuta and Spain's other territories in Africa, is subject to an irredentist claim by Morocco.[9]

Names

The original name (currently rendered as Rusadir) was a Punic language name, coming from the name given to the nearby Cape Three Forks. Addir meant "powerful".[10] The name creation is similar to that of other names given in Antiquity to outlets along the North African coast, including Rusguniae, Rusubbicari, Rusuccuru, Rusippisir, Rusigan (Rachgoun), Rusicade, Ruspina, Ruspe or Rsmlqr.[11]

Meanwhile, the etymology of the current city name (dating back to the 9th century, rendered as Melilla in Spanish) is uncertain. Since Melilla was an active beekeeping location in the past, the name has been related to honey; this is tentatively backed up by two ancient coins featuring a bee as well as the inscriptions RSADR and RSA.[12] Others relate the name to "discord" or "fever" or also to an ancient Arab personality.[12]

History

Antiquity and middle ages

It was a Phoenician and later Punic trade establishment under the name of Rusadir (Rusaddir for the Romans and Russadeiron (Ancient Greek: Ῥυσσάδειρον) for the Greeks). Later Rome absorbed it as part of the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana. Rusaddir is mentioned by Ptolemy (IV, 1) and Pliny (V, 18) who called it "oppidum et portus" (a fortified town and port). It was also cited by Mela (I, 33) as Rusicada, and by the Itinerarium Antonini.[13] Rusaddir was said to have once been the seat of a bishop, but there is no record of any bishop of the purported see,[13] which is not included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[14]

As centuries passed, it was ruled by Vandal, Byzantine and Visigoth bands. The political history is similar to that of towns in the region of the Moroccan Rif and southern Spain. Local rule passed through a succession of Phoenician, Punic, Roman, Umayyad, Cordobese, Idrisid, Almoravid, Almohad, Marinid, and then Wattasid rulers.

Early Modern period

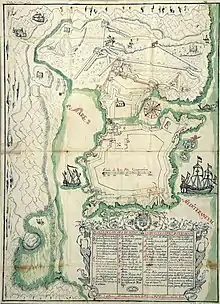

During the 15th century, the city subsumed into decadence, just like most of the rest of cities of the Kingdom of Fez located along the Mediterranean coast, eclipsed by those along the Atlantic facade.[15] Following the completion of the conquest of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, their Secretary Hernando de Zafra started to compile information about the sorry state of the north-African coast with the prospect of a potential territorial expansion in mind,[16] sending field agents to investigate, and subsequently reporting the Catholic Monarchs that, by early 1494, locals had expelled the authority of the Sultan of Fez and had offered to pledge service.[17] While the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas put Melilla and Cazaza (until then reserved to the Portuguese) under the sphere of Castile, the conquest of the city had to wait, delayed by the occupation of Naples by Charles VIII of France.[18]

The Duke of Medina Sidonia, Juan Alfonso Pérez de Guzmán promoted the seizure of the place, to be headed by Pedro de Estopiñán, while the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon endorsed the initiative, also providing the assistance of their artillery officer Francisco Ramírez de Madrid during the operation.[19] Melilla was occupied on 17 September 1497 virtually without any violence as it, located on the border between the Kingdom of Tlemcen and the Kingdom of Fez, and as a result, it had been fought over many times and so had been left abandoned.[20][21] No big-scale expansion into the Kingdom of Fez ensued, and, barring the enterprises of the Cardinal Cisneros along the coast in Mers El Kébir and Oran (in the Algerian coast), and the rock of Badis (this one in the territorial scope of the Kingdom of Fez), the imperial impetus of the Hispanic monarchy was eventually directed elsewhere, to the Italian Wars waged against France, and, particularly since 1519,[22] to the newly discovered continent across the Atlantic.

Melilla was initially jointly administered by the House of Medina Sidonia and the Crown,[23] and a 1498 settlement forced the former to station a 700-men garrison in Melilla and forced the latter to provide the city with a number of maravedíes and wheat fanegas.[24] The Crown's interest in Melilla decreased during the reign of Charles V.[25] During the 16th century, soldiers stationed in Melilla were badly remunerated, leading to many desertions.[26] The Duke of Medina Sidonia relinquished responsibility over the garrison of the place on 7 June 1556.[27]

During the late 17th century, Alaouite sultan Ismail Ibn Sharif attempted to conquer the presidio,[28] taking the outer fortifications in the 1680s and further unsuccessfully besieging Melilla in the 1690s.[29]

One Spanish officer reflected, "an hour in Melilla, from the point of view of merit, was worth more than thirty years of service to Spain."[30]

Late Modern period

The current limits of the Spanish territory around the Melilla fortress were fixed by treaties with Morocco in 1859, 1860, 1861, and 1894. In the late 19th century, as Spanish influence expanded in this area, the Crown authorized Melilla as the only centre of trade on the Rif coast between Tetuan and the Algerian frontier. The value of trade increased, with goat skins, eggs and beeswax being the principal exports, and cotton goods, tea, sugar and candles being the chief imports.

Melilla's civil population in 1860 still amounted for only 375 estimated inhabitants.[31] In a 1866 Hispano-Moroccan arrangement signed in Fes, both parts agreed to allow for the installment of a customs office near the border with Melilla, to be operated by Moroccan officials.[32] The Treaty of Peace with Morocco that followed the 1859–60 War entailed the acquisition of a new perimeter for Melilla, bringing its area to the 12 km2 the autonomous city currently stands.[33] Following the declaration of Melilla as free port in 1863, the population began to increase, chiefly by Sephardi Jews fleeing from Tetouan who fostered trade in and out the city.[34] The first Jews from Tetouan probably arrived in 1864,[35] meanwhile the first rabbi arrived in 1867 and began to operate the first synagogue, located in the Calle de San Miguel.[36] Many Jews arrived fleeing from persecution in Morocco, instigated by Roghi Bu Hamara.[37] Following the 1868 lifting of the veto to emigrate to Melilla from Peninsular Spain, the population further increased with Spaniards.[38] The Jewish population, who also progressively acquired Spanish citizenship, increased to 572 in 1893.[39] The economic opportunities created in Melilla henceforth favoured the installment of a Berber population.[38]

- Views of Melilla taken from an elevated position in 1893

The first proper body of local government was the junta de arbitrios, created in 1879,[40] and in which the military used to enjoy preponderance.[41] The Polígono excepcional de Tiro, the first neighborhood outside the walled core (Melilla la Vieja), began construction in 1888.[42]

.jpg.webp)

In 1893, Riffian tribesmen launched the First Melillan campaign to take back this area; the Spanish government sent 25,000 soldiers to defend against them. The conflict was also known as the Margallo War, after Spanish General Juan García y Margallo, Governor of Melilla, who was killed in the battle. The new 1894 agreement with Morocco that followed the conflict increased trade with the hinterland, bringing the economic prosperity of the city to a new level.[43] The total population of Melilla amounted for 10,004 inhabitants in 1896.[44]

The turn of the new century saw however the attempts by France (based in French Algeria) to profit from their newly acquired sphere of influence in Morocco to counter the trading prowess of Melilla by fostering trade links with the Algerian cities of Ghazaouet and Oran.[45] Melilla began to suffer from this, to which the instability brought by revolts against Muley Abdel Aziz in the hinterland also added,[46] although after 1905 Sultan pretender El Rogui (Bou Hmara) carried out a defusing policy in the area that favoured Spain.[47] The French occupation of Oujda in 1907, compromised the Melillan trade with that city.[48] and the enduring instability in the Rif still threatened Melilla.[49] Between 1909 and 1945, the modernista (Art Nouveau) style was very present in the local architecture, making the streets of Melilla a "true museum of modernista-style architecture", second only to Barcelona (in Spain), mainly stemming from the work of prolific architect Enrique Nieto.[50]

Mining companies began to enter the hinterland of Melilla by 1908.[51] A Spanish one, the Compañía Española de las Minas del Rif, was constituted in July 1908, shared by Clemente Fernández, Enrique Macpherson, the Count of Romanones, the Duke of Tovar and Juan Antonio Güell, who appointed Miguel Villanueva as chairman.[52] Thus two mining companies under the protection of Bou Hmara, started mining lead and iron some 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) from Melilla. They started to construct a railway between the port and the mines. In October of that year, Bou Hmara's vassals revolted against him and raided the mines, which remained closed until June 1909. By July the workmen were again attacked and several were killed. Severe fighting between the Spaniards and the tribesmen followed, in the Second Melillan campaign that took place in the vicinity of Melilla.

In 1910, the Spaniards restarted the mines and undertook harbor works at Mar Chica, but hostilities broke out again in 1911. On 22 July 1921, the Berbers under the leadership of Abd el Krim inflicted a grave defeat on the Spanish at the Battle of Annual. The Spanish retreated to Melilla, leaving most of the protectorate under the control of the Republic of Rif.

A royal decree pursuing the creation of an ayuntamiento in Melilla was signed on 13 December 1918 but the regulation did not come into force, and thus the existing government body, the junta de arbitrios, remained in force.[53]

A "junta municipal" with a rather civil composition was created in 1927; on 10 April 1930, an ayuntamiento featuring the same membership as the junta was created,[54] equalling to the same municipal regime as the rest of Spain on 14 April 1931, with the arrival of the first democratically elected municipal corporation on the wake of the proclamation of the Second Republic.[55]

The city was used as one of the staging grounds for the July 1936 military coup d'état that started the Spanish Civil War.

In the context of the passing of the Ley de Extranjería in 1986, and following social mobilization from the Berber community, conditions for citizenship acquisition were flexibilised and allowed for the naturalisation of a substantial number of inhabitants, until then born in Melilla but without Spanish citizenship.[56]

Recent developments

In 1995, Melilla (which was until then just another municipality of the Province of Málaga) became an "autonomous city",[57] as the Statute of Autonomy of Melilla was passed.

On 6 November 2007, King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofia visited the city, which caused a demonstration of support. The visit also sparked protests from the Moroccan government.[58] It was the first time a Spanish monarch had visited Melilla in 80 years.

Melilla (and Ceuta) declared the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha or Feast of the Sacrifice, as an official public holiday from 2010 onward. It is the first time a non-Christian religious festival has been officially celebrated in Spain since the Reconquista.[59][60]

In 2018, Morocco decided to close the customs office near Melilla, in operation since the mid-19th century, without consulting the counterparty.[61]

Geography

Location

_ISS-36_Strait_of_Gibraltar_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Melilla is located in the northwest of the African continent, on the shores of the Alboran Sea, a marginal sea of the Mediterranean, the latter's westernmost portion. The city layout is arranged in a wide semicircle around the beach and the Port of Melilla, on the eastern side of the peninsula of Cape Tres Forcas, at the foot of Mount Gurugú and around the mouth of the Río de Oro intermittent water stream, 1 meter (3 ft 3 in) above sea level. The urban nucleus was originally a fortress, Melilla la Vieja, built on a peninsular mound about 30 meters (98 ft) in height.

The Moroccan settlement of Beni Ansar lies immediately south of Melilla. The nearest Moroccan city is Nador, and the ports of Melilla and Nador are both within the same bay; nearby is the Bou Areg Lagoon.[62]

Climate

Melilla has a warm Mediterranean climate influenced by its proximity to the sea, rendering much cooler summers and more precipitation than inland areas deeper into Africa. The climate, in general, is similar to the southern coast of peninsular Spain and the northern coast of Morocco, with relatively small temperature differences between seasons.

| Climate data for Melilla 47 m (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

34.2 (93.6) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.0 (98.6) |

41.8 (107.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.9 (62.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.3 (2.18) |

48.2 (1.90) |

43.6 (1.72) |

37.7 (1.48) |

15.2 (0.60) |

7.2 (0.28) |

0.5 (0.02) |

3.8 (0.15) |

18.9 (0.74) |

42.6 (1.68) |

53.3 (2.10) |

48.2 (1.90) |

374.5 (14.75) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 43 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 194 | 188 | 214 | 232 | 277 | 299 | 305 | 280 | 223 | 205 | 184 | 179 | 2,780 |

| Source: Météo Climat[63] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Melilla 47 m (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

34.2 (93.6) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.0 (98.6) |

41.8 (107.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58 (2.3) |

57 (2.2) |

44 (1.7) |

36 (1.4) |

20 (0.8) |

7 (0.3) |

1 (0.0) |

4 (0.2) |

16 (0.6) |

40 (1.6) |

57 (2.2) |

50 (2.0) |

391 (15.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 44 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 74 | 73 | 69 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 69 | 72 | 75 | 74 | 73 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 184 | 170 | 192 | 220 | 258 | 279 | 289 | 268 | 210 | 194 | 176 | 168 | 2,607 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[64] | |||||||||||||

Government and administration

Self-government institutions

The government bodies stipulated in the Statute of Autonomy are the Assembly of Melilla, the President of Melilla and the Council of Government. The assembly is a 25-member body whose members are elected through universal suffrage every 4 years in closed party lists following the schedule of local elections at the national level. Its members are called "local deputies" but they rather enjoy the status of concejales (municipal councillors).[65] Unlike regional legislatures (and akin to municipal councils), the assembly does not enjoy right of initiative for primary legislation.[66]

The president of Melilla (who, often addressed as Mayor-President, also exerts the roles of Mayor, president of the Assembly, president of the Council of Government and representative of the city)[67] is invested by the Assembly. After local elections, the president is invested through a qualified majority from among the leaders of the election lists, or, failing to achieve the former, the leader of the most voted list at the election is invested to the office.[68] In case of a motion of no confidence the president can only be ousted with a qualified majority voting for an alternative assembly member.[68]

The Council of Government is the traditional collegiate executive body for parliamentary systems. Unlike the municipal government boards in the standard ayuntamientos, the members of the Council of Government (including the vice-presidents) do not need to be members of the assembly.[69]

Melilla is the city in Spain with the highest proportion of postal voting;[70] vote buying (via mail-in ballots) is widely reported to be a common practice in the poor neighborhoods of Melilla.[70] Court cases in this matter had involved the PP, the CPM and the PSOE.[70]

On 15 June 2019, following the May 2019 Melilla Assembly election, the regionalist and left-leaning party of Muslim and Amazigh persuasion Coalition for Melilla (CPM, 8 seats), the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE, 4 seats) and Citizens–Party of the Citizenry (Cs, 1 seat) voted in favour of the Cs' candidate (Eduardo de Castro) vis-à-vis the Presidency of the Autonomous City,[71][72] ousting Juan José Imbroda, from the People's Party (PP, 10 seats), who had been in office since 2000.

Administrative subdivisions

Melilla is subdivided into eight districts (distritos), which are further subdivided into neighbourhoods (barrios):

- 1st

- Barrio de Medina Sidonia.

- Barrio del General Larrea.

- Barrio de Ataque Seco.

- 2nd

- Barrio Héroes de España.

- Barrio del General Gómez Jordana.

- Barrio Príncipe de Asturias.

- 3rd

- Barrio del Carmen.

- 4th

- Barrio Polígono Residencial La Paz.

- Barrio Hebreo-Tiro Nacional.

- 5th

- Barrio de Cristóbal Colón.

- Barrio de Cabrerizas.

- Barrio de Batería Jota.

- Barrio de Hernán Cortes y Las Palmeras.

- Barrio de Reina Regente.

- 6th

- Barrio de Concepción Arenal.

- Barrio Isaac Peral (Tesorillo).

- 7th

- Barrio del General Real.

- Polígono Industrial SEPES.

- Polígono Industrial Las Margaritas.

- Parque Empresarial La Frontera.

- 8th

- Barrio de la Libertad.

- Barrio del Hipódromo.

- Barrio de Alfonso XIII.

- Barrio Industrial.

- Barrio Virgen de la Victoria.

- Barrio de la Constitución.

- Barrio de los Pinares.

- Barrio de la Cañada de Hidum

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the autonomous community was 1.6 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 0.1% of Spanish economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 19,900 euros or 66% of the EU27 average in the same year. Melilla was the NUTS2 region with the lowest GDP per capita in Spain.[73]

Melilla does not participate in the European Union Customs Union (EUCU).[74] There is no VAT (IVA) tax, but a local reduced-rate tax called IPSI.[75] Preserving the status of free port, imports are free of tariffs and the only tax concerning them is the IPSI.[76] Exports to the Customs Union (including Peninsular Spain) are however subject to the correspondent customs tariff and are taxed with the correspondent VAT.[76] There are some special manufacturing taxes regarding electricity and transport, as well as complementary charges on tobacco and oil and fuel products.[77]

The principal industry is fishing. Cross-border commerce (legal or smuggled) and Spanish and European grants and wages are the other income sources.

Melilla is regularly connected to the Iberian peninsula by air and sea traffic and is also economically connected to Morocco: most of its fruit and vegetables are imported across the border. Moroccans in the city's hinterland are attracted to it: 36,000 Moroccans cross the border daily to work, shop or trade goods.[78] The port of Melilla offers several daily connections to Almería and Málaga. Melilla Airport offers daily flights to Almería, Málaga and Madrid. Spanish operators Air Europa and Iberia operate in Melilla's airport.

Many people travelling between Europe and Morocco use the ferry links to Melilla, both for passengers and for freight. Because of this, the port and related companies form an important economic driver for the city.[78]

Water supply

Melilla's water supply primarily came from a network of dug wells (which by the turn of the 21st century suffered from overexploitation and had also experienced a degradation of the water quality and the intrusion of seawater),[79] as well as from the capture of the Río de Oro's underflow.[80] Seeking to address the problem of water supply in Melilla, works for the construction of a desalination plant in the Aguadú cliffs, projected to produce 22,000 m3 (29,000 cu yd) a day, started in November 2003.[81] The plant entered operation in March 2007.[82] The daily operation of the plant is partially funded by the central government.[83] Relative to the Spanish average (and similarly to the Canary and Balearic Islands), the city's population spends a comparatively larger amount of money on bottled water.[84]

Funded by the European Regional Development Fund and the Confederación Hidrográfica del Guadalquivir, works for the expansion of the plant's production capabilities up to 30,000 m3 (39,000 cu yd) a day started by September 2020.[85]

Architecture

The dome of the Chapel of Santiago, built in the mid-16th century by Miguel de Perea with help from Sancho de Escalante, is a rare instance of Gothic architecture in the African continent.[86]

Parallel to the urban development of Melilla in the early 20th century, the new architectural style of modernismo (irradiated from Barcelona and associated to the bourgeois class) was imported to the city, granting it a modernista architectural character, primarily through the works of the prolific Catalan architect Enrique Nieto.[87]

Accordingly, Melilla has the second most important concentration of Modernista works in Spain after Barcelona.[87] Nieto was in charge of designing the main Synagogue, the Central Mosque and various Catholic Churches.[88]

Dome of the Chapel of Santiago

Dome of the Chapel of Santiago Modernista building, former headquarters of El Telegrama del Rif newspaper.

Modernista building, former headquarters of El Telegrama del Rif newspaper._(5446069722).jpg.webp) Local synagogue

Local synagogue Melilla's central mosque

Melilla's central mosque

Demographics

Religion

.jpg.webp)

Melilla has been praised as an example of multiculturalism, being a small city in which one can find Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, and Buddhists represented. There is a small, autonomous, and commercially important Hindu community present in Melilla, which has fallen over the past decades as its members move to the Spanish mainland and numbers about 100 members today.[89] Muslims may account for roughly half the population in Melilla.[90]

The Roman Catholic churches in Melilla belong to the Diocese of Málaga.[91]

Language

Regarding sociolinguistics, Melilla features a diglossia with Spanish being the strong and official language, whereas Tarifit remains the weak and unofficial language, with limited written codification, and usage restricted to family and domestic relations and oral speech.[8]

The population can be thus divided in 1st) monolingual Spanish speakers of European ethnic origin (without competence in any other language than those formally taught at school); 2nd, those descent of Tamazight-speaking parents, usually bilingual in Spanish and Tamazight; and 3rd, Moroccan immigrants and cross-border workers, with a generally dominant Tamazight language (with some also featuring competence in Arabic) and a L2 competence in Spanish.[92] The Spanish spoken in Melilla is similar to the Andalusian variety from Cádiz,[93] whereas the Berber variant spoken in Melilla is the Riffian language common with the neighbouring Nador area.[94] Rather than Berber (Spanish: bereber), Berber speakers in Melilla use either the glotonym Tmaziɣt, or, when speaking Spanish, cherja for their language.[93]

The first attempt to legislate a degree of recognition for Berber in Melilla was in 1994, in the context of the elaboration of the Statute of Autonomy, by mentioning the promotion of the linguistic and cultural pluralism (without explicitly mentioning the Berber language). The initiative went nowhere, voted down by PP and PSOE.[95] Reasons cited for not recognizing Tamazight are related to the argument that the variety is not standardized.[96]

Border dynamics

Trans-border relations

Melilla forms a sort of trans-border urban conurbation with limited integration together with the neighbouring Moroccan settlements, located at one of the ends of a linear succession of urban sprawl spanning southward in Morocco along the R19 road from Beni Ensar down to Nador and Selouane.[97] The urban system features a high degree of hierarchization, specialization and division of labour, with Melilla as chief provider of services, finance and trade; Nador as an eminently industrial city whereas the rest of Moroccan settlements found themselves in a subordinate role, presenting agro-town features and operating as providers of workforce.[97]

The asymmetry, as reflected for example in the provision of healthcare, has fostered situations such as the large-scale use of the Melillan health services by Moroccan citizens, with Melilla attending a number of urgencies more than four times the standard for its population in 2018.[98] In order to satisfy the workforce needs of Melilla (mainly in areas such as domestic service, construction and cross-border bale workers, often under informal contracts), Moroccan inhabitants of the province of Nador were granted exemptions from visa requirement to enter the autonomous city.[99] This development in turn induced a strong flux of internal migration from other Moroccan provinces to Nador, in order to acquire the aforementioned exemption.[99]

The 'fluid' trans-border relations between Melilla and its surroundings are however not free from conflict, as they are contingent upon the 'tense' trans-national relations between Morocco and Spain.[100]

Border securitization

Following the increasing influx of Algerian and sub-Saharan irregular migrants into Ceuta and Melilla in the early 1990s,[101] a process of border fortification in both cities ensued after 1995 in order to reduce the border permeability,[102][103] a target which was attained to some degree by 1999,[101] although peak level of fortification was reached in 2005.[102]

The Melilla's border with Morocco is secured by the Melilla border fence, a 6 metres (20 ft) tall double fence with watch towers; yet migrants (in groups of tens or sometimes hundreds) storm the fence and manage to cross it from time to time.[104] Since 2005, at least 14 migrants have died trying to cross the fence.[105] The Melilla migrant reception centre was built with a capacity of 480.[106] In 2020 works to remove the barbed wire from the top of the fence (meanwhile raising its height up to more than 10 metres (33 ft) in the stretches most susceptible to breaches) were commissioned to Tragsa.[107]

In June 2022, at least 23 sub-Saharan migrants and two Moroccan security personnel were killed when around 2000 migrants stormed the border in an attempt to cross into Melilla. The death toll has been estimated to be as high as 37 by certain NGOs.[108] Around 200 Spanish and Moroccan law enforcement officers and at least 76 migrants were injured. Hundreds of migrants succeeded in breaching the fence, and 133 made it across the border.[109] Widely circulated footage showed dozens of motionless migrants piled together.[110] It was the worst such incident in Melilla's history.[111] The United Nations, the African Union and a number of human rights groups condemned what they deemed excessive force used by Moroccan and Spanish border guards, although no lethal weapons were employed, and the deaths were later attributed to "mechanical asphyxiation".[112]

Morocco has been paid tens of million euros by both Spain and the European Union to outsource the EU migration control.[113] Besides the double fence in the Spanish side of the border, there is an additional 3 metres (9.8 ft) high fence entirely made of razor wire lying on the Moroccan side as well as a moat in between.[113]

Transportation

Melilla Airport is serviced by Air Nostrum, flying to the Spanish cities of Málaga, Madrid, Barcelona, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Palma de Mallorca, Granada, Badajoz, Sevilla and Almería. In April 2013, a local enterprise set up Melilla Airlines, flying from the city to Málaga.[114] The city is linked to Málaga, Almería and Motril by ferry.

Three roads connect Melilla and Morocco but require clearance through border checkpoints.

Sport

Melilla is a surfing destination.[115] The city's football club, UD Melilla, plays in the third tier of Spanish football, the Segunda División B. The club was founded in 1943 and since 1945 have played at the 12,000-seater Estadio Municipal Álvarez Claro. Until the other club was dissolved in 2012, UD Melilla played the Ceuta-Melilla derby against AD Ceuta. The clubs travelled to each other via the Spanish mainland to avoid entering Morocco.[116] The second-highest ranked club in the city are Casino del Real CF of the fourth-tier Tercera División. The football's governing institution is the Melilla Football Federation.

Dispute with Morocco

The government of Morocco has repeatedly called for Spain to transfer the sovereignty of Ceuta and Melilla, along with uninhabited islets such as the Alhucemas Islands, the rock of Vélez de la Gomera and the Perejil island, drawing comparisons with Spain's territorial claim to Gibraltar. In both cases, the national governments and local populations of the disputed territories reject these claims by a large majority.[117] The Spanish position states that both Ceuta and Melilla are integral parts of Spain, and have been since the 16th century, centuries prior to Morocco's independence from France in 1956, whereas Gibraltar, being a British Overseas Territory, is not and never has been part of the United Kingdom.[118] Both cities also have the same semi-autonomous status as the mainland region in Spain. Melilla has been under Spanish rule for longer than cities in northern Spain such as Pamplona or Tudela, and was conquered roughly in the same period as the last Muslim cities of Southern Spain such as Granada, Málaga, Ronda or Almería: Spain claims that the enclaves were established before the creation of the Kingdom of Morocco. Morocco denies these claims and maintains that the Spanish presence on or near its coast is a remnant of the colonial past which should be ended. The United Nations list of non-self-governing territories does not include these Spanish territories and the dispute remains bilaterally debated between Spain and Morocco.[117][119]

In 1986, Spain entered the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. However Ceuta and Melilla are not under NATO protection since Article 6 of the treaty limits the coverage to Europe and North America and islands north of the Tropic of Cancer. This contrasts with French Algeria which was explicitly included in the treaty. Legal experts have interpreted that other articles could cover the Spanish North African cities but this take has not been tested in practice.[120]

On 21 December 2020, following the affirmations of the Moroccan Prime Minister, Saadeddine Othmani, stating that Ceuta and Melilla "are Moroccan as the [Western] Sahara [is]", Spain urgently summoned the Moroccan Ambassador to convey that Spain expects respect from all its partners to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of its country and asked for explanations about the words of Othmani.[121][122]

Twin towns – sister cities

Melilla is twinned with:

Caracas (Venezuela).[123]

Caracas (Venezuela).[123] Cavite City (Philippines).

Cavite City (Philippines). Ceuta (Spain).[124]

Ceuta (Spain).[124] Toledo (Spain).

Toledo (Spain). Málaga (Spain).

Málaga (Spain). Montevideo (Uruguay).[125]

Montevideo (Uruguay).[125] Motril (Spain); since January 2008.[126]

Motril (Spain); since January 2008.[126] Almería (Spain).[127]

Almería (Spain).[127] Mantua (Italy); since September 2013.[128]

Mantua (Italy); since September 2013.[128] Vélez-Málaga (Spain); since January 2014.[129]

Vélez-Málaga (Spain); since January 2014.[129] Antequera (Spain); as of 2016, in process.[130]

Antequera (Spain); as of 2016, in process.[130]

See also

- European enclaves in North Africa before 1830

- Melilla (Congress of Deputies constituency)

References

- Citations

- Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- "Melilla" (US) and "Melilla". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- "Melilla". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- Yahia, Jahfar Hassan (2014). Curso de lengua tamazight, nivel elemental. Caminando en la didáctica de la lengua rifeña (in Spanish and Riffian). Melilla: GEEPP Ed.

- Council of the European Union (2015). The Schengen Area (PDF). Council of the European Union. doi:10.2860/48294. ISBN 978-92-824-4586-0.

- "Cifras oficiales de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal a 1 de enero". Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Trinidad 2012, p. 962.

- Sánchez Suárez 2003, p. 190.

- Trinidad 2012, pp. 961–975.

- López Pardo 2015, pp. 137.

- López Pardo 2015, pp. 137–138.

- Lara Peinado 1998, p. 25.

- Sophrone Pétridès, "Rusaddir" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1912)

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 960

- Bravo Nieto 1990, pp. 21–22.

- Bravo Nieto 1990, p. 25.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 83.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, pp. 83–84.

- Bravo Nieto 1990, p. 26.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 85; Bravo Nieto 1990, p. 26

- Ayuntamientos de España, Ayuntamiento.es, archived from the original on 1 March 2012, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Bravo Nieto 1990, pp. 17, 28.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 127.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 125.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 131.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, pp. 127–128.

- Polo 1986, p. 8.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 175.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, pp. 175–176, 179.

- Rezette, p. 41

- Saro Gandarillas 1985, p. 23.

- Remacha 1994, p. 218.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 99–100.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 100.

- Díaz Rodríguez 2011, p. 67.

- Díaz Rodríguez 2011, p. 68.

- Fernández García 2015, p. 108.

- López Guzmán et al. 2007, p. 11.

- Díaz Rodríguez 2011, pp. 67–68.

- Saro Gandarillas 1985, p. 24.

- Morala Martínez 2015, pp. 107–108.

- Cantón Fernández & Riaño López 1984, p. 18.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 102.

- Perpén Rueda 1987, p. 289.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 107.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 106–108.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 113–114.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 110–115.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 120.

- Cantón Fernández & Riaño López 1984, pp. 16, 19.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 121.

- Escudero 2014, p. 331.

- Morala Martínez 1985, pp. 107–108.

- Morala Martínez 1985, p. 120.

- Fernández Díaz 2009, pp. 25, 27.

- Fernández García 2015, p. 110.

- Bascón Jiménez et al. 2016, p. 47.

- "Mohamed VI "condena" y "denuncia" la visita "lamentable" de los Reyes de España a Ceuta y Melilla", El País, Elpais.com, 6 November 2007, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Muslim Holiday in Ceuta and Melilla, Spainforvisitors.com, archived from the original on 29 September 2011, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Public Holidays and Bank Holidays for Spain, Qppstudio.net, archived from the original on 30 September 2011, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Cembrero, Ignacio (2 December 2019). "Marruecos pone fin al contrabando con Ceuta y asfixia la ciudad". El Confidencial.

- World Port Source about Port Nador, retrieved 10 June 2012

- "Météo climat stats Moyennes 1991/2020 Espagne (page 2)" (in French). Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- "Valores climatológicos normales (1981–2010). Melilla". Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, pp. 10–11.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, p. 11.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, p. 12.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, pp. 14.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, pp. 12–13.

- Bautista, José (6 May 2019). "Se compran votos por 50 euros". El Confidencial.

- "Resultados Electorales en Melilla: Elecciones Municipales 2019 en EL PAÍS". El País. Resultados.elpais.com. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Alba, Nicolás (15 June 2019). "El único diputado de Ciudadanos consigue la presidencia de Melilla tras 19 años de Gobierno del PP". El Mundo. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- Morón 2006, p. 64.

- Morón Pérez 2006, p. 67.

- Morón Pérez 2006, pp. 67–68.

- Morón Pérez 2006, p. 68.

- English translation of Volkskrant article: Melilla North-Africa's European dream Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 5 August 2010, visited 3 June 2012

- "El trabajo de la desalinizadora mejora la calidad del agua y la sitúa en los parámetros exigidos por Sanidad y Consumo". 20 February 2008.

- "Melilla ahorrará un 6% de agua a partir de la segunda fase de planificación hidrológica". Europa Press. 29 July 2014.

- Ronda, Javier (January 2004). "Adiós al problema del agua en Melilla" (PDF). Ambienta.

- "Espinosa anuncia una inversión de 10 millones para ampliar la desalinizadora de Melilla". Europa Press. 29 September 2009.

- "El Gobierno financia con 3,9 millones el funcionamiento de la desalinizadora". Diario Sur. 24 September 2013.

- Villarreal, Antonio; Ojeda, Darío (9 April 2021). "Las dos Españas del agua: al oeste se tira más del grifo y en el resto aprecian la embotellada". El Confidencial.

- "Arrancan los trabajos para la ampliación de la desaladora de Melilla". El Faro de Melilla. 7 September 2020.

- Bravo Nieto 2002, p. 37.

- Cantón Fernández & Riaño López 1984, pp. 15–19.

- "Melilla Modernista". Melilla Turismo. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

Nieto was in charge of designing the main Synagogue, the Central Mosque and various Catholic churches

- "Melilla: Where Catalan "Modernisme" Meets North Africa". Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Ponce Herrero & Martí Ciriquián 2019, p. 117.

- Rodríguez, José Vicente (31 May 2014). "El 37% de las declaraciones de la Renta en Málaga marcan la X para la Iglesia". La Opinión de Málaga.

- Montero Alonso & Sayahi 2021, p. 56.

- Tilmatine 2011, p. 23.

- Tilmatine 2011, p. 26.

- Tilmatine 2011, p. 19.

- Montero Alonso & Sayahi 2021, p. 58.

- Ponce Herrero & Martí Ciriquián 2019, p. 115.

- Ponce Herrero & Martí Ciriquián 2019, p. 116.

- Ponce Herrero & Martí Ciriquián 2019, p. 109.

- Ponce Herrero & Martí Ciriquián 2019, p. 118.

- Ferrer Gallardo 2008, p. 140.

- Castellano, Nicolás (14 June 2016). "Preguntas y respuestas sobre 20 kilómetros de cuchilas en Ceuta y Melilla". Cadena Ser.

- Ferrer Gallardo, Xavier (2008). "Acrobacias fronterizas en Ceuta y Melilla. Explorando la gestión de los perímetros terrestres de la Unión Europea en el continente africano" (PDF). Documents d'anàlisi geogràfica. Bellaterra: Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (51): 134. ISSN 2014-4512.

- "BBC News - Hundreds breach Spain enclave border". BBC News. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- "Al menos 27 inmigrantes han fallecido desde 2005 tras los asaltos a la valla". ABC. 6 February 2014.

- "African migrants storm into Spanish enclave of Melilla". BBC. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Mata, Alejandro (16 August 2020). "La nueva valla de Ceuta y Melilla será un metro más alta que el muro de Trump". El Confidencial.

- "Calls for investigation over deaths in Moroccan-Spanish border crossing". the Guardian. 26 June 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "Death toll rises to 23 in Melilla border-crossing stampede". POLITICO. 26 June 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Eljechtimi, Ahmed; Keeley, Graham (25 June 2022). "Dozens of migrants piled together at Melilla border fence". Reuters. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "Melilla migrant deaths spark anger in Spain". BBC News. 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "Moroccan probe finds 23 Melilla border dead likely 'suffocated'". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Muñoz Medina, Lucía (29 August 2020). "Menos concertinas y más altura: colectivos de Melilla y Ceuta denuncian que las nuevas vallas continúan vulnerando los derechos humanos". Público.

- "Una nueva compañía aérea comunica Melilla con Málaga tras la marcha de Helitt – Transporte aéreo – Noticias, última hora, vídeos y fotos de Transporte aéreo en lainformacion.com". Noticias.lainformacion.com. 28 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- "Melilla - Weather Stations". Magicseaweed.com. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Hawkey, Ian (2009). Feet of the chameleon : the story of African football. London: Portico. ISBN 978-1-906032-71-5.

-

- François Papet-Périn, "La mer d'Alboran ou Le contentieux territorial hispano-marocain sur les deux bornes européennes de Ceuta et Melilla". Tome 1, 794 p., tome 2, 308 p., thèse de doctorat d'histoire contemporaine soutenue en 2012 à Paris 1-Sorbonne sous la direction de Pierre Vermeren.

- Tremlett, Giles (12 June 2003). "A rocky relationship | World news | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- Govan, Fiona (10 August 2013). "The battle over Ceuta, Spain's African Gibraltar". The Telegraph. Ceuta. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- "¿Están Ceuta y Melilla bajo el paraguas de la OTAN?". Newtral (in Spanish). 2 October 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- elDiario.es (21 December 2020). "España convoca a la embajadora de Marruecos por unas declaraciones de su primer ministro sobre Ceuta y Melilla". ElDiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- AfricaNews (22 December 2020). "Moroccan Ambassador to Spain summoned over calls for territorial sovereignty talks". Africanews. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Melilla y Venezuela, más cerca que nunca". Diario Sur. 10 February 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- "Ceuta, Melilla profile". BBC News. 14 December 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- "Melilla se hermana con Montevideo para unir lazos y promocionar valores". InfoMelilla. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Rubio Cano, Begoña (18 January 2008). "El presidente de Melilla y el alcalde de Motril hermanan a las dos ciudades y firman un convenio". Diario Sur.

- Revilla, María Victoria (19 October 2010). "Almería se hermana con los Emiratos Árabes y abre nuevas vías de negocio". Diario de Almería.

- "Mantua, hermana e invitada de honor". El Faro de Melilla. 17 September 2013.

- "Vélez y Melilla, dos ciudades hermanadas". Diario Sur. 10 January 2013.

- "Melilla y Antequera comienzan los trámites de hermanamiento el próximo septiembre". El Faro de Melilla. 1 July 2016.

- Bibliography

- Bascón Jiménez, Milagrosa; Cazallo Antúnez, Ana; Lechuga Cardozo, Jorge; Meñaca Guerrero, Indira (2016). "Necesidad de implantar un servicio público de transporte entre las ciudades de Ceuta-Tetuán y Melilla-Nador". Desarrollo Gerencial. Barranquilla: Universidad Simón Bolívar. 8 (2): 37–57. doi:10.17081/dege.8.2.2553.

- Bravo Nieto, Antonio (1990). "La ocupación de Melilla en 1497 y las relaciones entre los Reyes Católicos y el Duque de Medina Sidonia". Aldaba. Melilla: UNED (15): 15–37. doi:10.5944/aldaba.15.1990.20168. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Bravo Nieto, Antonio (2002). "Tradición y modernidad en el Renacimiento español: la Puerta y Capilla de Santiago de Melilla" (PDF). Akros: Revista de Patrimonio (1): 36–41. ISSN 1579-0959.

- Cantón Fernández, Laura; Riaño López, Ana (1984). "El ámbito modernista de Melilla" (PDF). Aldaba (3): 11–25. doi:10.5944/aldaba.3.1984.19523. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Díaz Rodríguez, Ángeles (2011). "El sillón de estudio del Rabino Abraham Hacohen" (PDF). Akros (10): 67–70. ISSN 1579-0959.

- Escudero, Antonio (2014). "Las minas de Guelaya y la Guerra del Rif" (PDF). Pasado y Memoria. Revista de Historia Contemporánea. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante (13): 329–336. ISSN 1579-3311.

- Fernández Díaz, María Elena (2009). "La instauración del primer Ayuntamiento de Melilla" (PDF). Akros: Revista de Patrimonio (8): 25–30. ISSN 1579-0959.

- Fernández García, Alicia (2015). "Repensar las fronteras lingüísticas del territorio español: Melilla, entre mosaico sociológico y paradigma lingüístico" (PDF). ELUA. Estudios de Lingüística. San Vicente del Raspeig: Universidad de Alicante. 29 (29): 105–126. doi:10.14198/ELUA2015.29.05.

- Lara Peinado, Fernando (1998). "Melilla: entre Oriente y Occidente" (PDF). Aldaba. Melilla: UNED (30): 13–34. ISSN 0213-7925.

- López Guzmán, Tomás J.; González Fernández, Virgilio; Herrera Torres, Lucía; Lorenzo Quiles, Oswaldo (2007). "Melilla: ciudad fronteriza internacional e intercontinental. Análisis histórico, económico y educativo" (PDF). Frontera Norte. Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, A.C. 19 (37): 7–33.

- López Pardo, Fernando (2015). "La fundación de Rusaddir y la época púnica". Gerión. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. 33: 135–156. doi:10.5209/rev_GERI.2015.49055. ISSN 0213-0181.

- Loureiro Soto, Jorge Luis (2015). Los conflictos por Ceuta y Melilla: 600 años de controversias (PDF). UNED.

- Márquez Cruz, Guillermo (2003). "La formación de gobierno y la práctica coalicional en las ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla (1979-2007)" (PDF). Working Papers. Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials (227). ISSN 1133-8962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Montero Alonso, Miguel Ángel; Sayahi, Lotfi (2021). "Bilingüismo y actitud lingüística en Melilla (España)". Lengua y migración. Alcalá de Henares: Editorial Universidad de Alcalá. 13 (1): 55–75. doi:10.37536/LYM.13.1.2021.1363. ISSN 1889-5425. S2CID 237911620.

- Morala Martínez, Paulina (1985). "Reformas de la administración local durante la Dictadura: de la Junta de Arbitrios a la Junta Municipal (1923–1927)" (PDF). Aldaba (40): 107–120.

- Morón Pérez, María del Carmen (2006). "El régimen fiscal de las ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla: presente y futuro" (PDF). Crónica Tributaria (121): 59–96. ISSN 0210-2919.

- Perpén Rueda, Adoración (1987). "La masonería en Melilla en el s. XIX: las logias 'Amor' y 'Africa'" (PDF). In Ferrer Benimeli, José Antonio (ed.). La masonería en la España del siglo XIX. Vol. I. pp. 289–296. ISBN 84-505-5233-8.

- Polo, Monique (1986). "La vida cotidiana en Melilla en el siglo XVI" (PDF). Criticón (36): 8. ISSN 0247-381X – via Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

- Ponce Herrero, Gabino; Martí Ciriquián, Pablo (2019). "El complejo urbano transfronterizo Melilla-Nador" (PDF). Investigaciones Geográficas. Alicante: San Vicente del Raspeig (72): 101–124. doi:10.14198/INGEO2019.72.05. hdl:10045/99969. ISSN 1989-9890. S2CID 213966829.

- Remacha Tejada, José Ramón (1994). "Las fronteras de Ceuta y Melilla" (PDF). Anuario Español de Derecho Internacional. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra (10): 195–238. ISSN 0212-0747.

- Sánchez Suárez, Mª Ángeles (2003). "Reflexiones acerca de la enseñanza del español como lengua de segunda adquisición a personas adultas hablantes de tamazight". Aldaba (29): 189–235. doi:10.5944/aldaba.29.2003.20438.

- Saro Gandarillas, Francisco (1985). "La expansión urbana de Melilla: aproximación a su estudio" (PDF). Aldaba. 3 (5): 23–34. doi:10.5944/aldaba.5.1985.19602.

- Saro Gandarillas, Francisco (1993). "Los orígenes de la Campaña del Rif de 1909". Aldaba. Melilla: UNED (22): 97–130. doi:10.5944/aldaba.22.1993.20298. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Tilmatine, Mohand (2011). "El contacto español-bereber: la lengua de los informativos en Melilla". Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana. 9 (2): 15–45. JSTOR 41678469.

- Trinidad, Jamie (2012). "An Evaluation of Morocco's Claims to Spain's Remaining Territories in Africa". International and Comparative Law Quarterly. Cambridge University Press. 61 (4): 961–975. doi:10.1017/S0020589312000371. ISSN 0020-5893. JSTOR 23279813. S2CID 232180584.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Melilla". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 94.

External links

- (in Spanish) Official website

- Postal Codes Melilla

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)