I-35W Mississippi River bridge

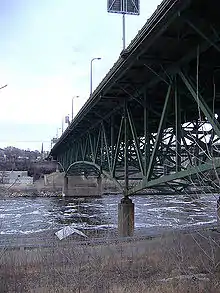

The I-35W Mississippi River bridge (officially known as Bridge 9340) was an eight-lane, steel truss arch bridge that carried Interstate 35W across the Mississippi River one-half mile (875 m) downstream from the Saint Anthony Falls in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. The bridge opened in 1967 and was Minnesota's third busiest,[4][5] carrying 140,000 vehicles daily.[3] It experienced a catastrophic failure during the evening rush hour on August 1, 2007, killing 13 people and injuring 145. The NTSB cited a design flaw as the likely cause of the collapse, noting that an excessively thin gusset plate ripped along a line of rivets, and that additional weight on the bridge at the time contributed to the catastrophic failure.[6]

I-35W Mississippi River bridge | |

|---|---|

Bridge 9340 in May 2006 (one year prior to collapse) | |

| Coordinates | 44°58′44″N 93°14′42″W |

| Carries | 8 lanes of |

| Crosses | Mississippi River |

| Locale | Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Official name | Bridge 9340 |

| Maintained by | Minnesota Department of Transportation (Mn/DOT) |

| ID number | 9340 |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Continuous truss bridge |

| Total length | 1,907 ft (581.3 m) |

| Width | 113.3 ft (34.5 m) |

| Height | 115 ft (35.1 m) |

| Longest span | 456 ft (139 m)[1] |

| Clearance below | 64 ft (19.5 m) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1964[2] |

| Opened | November 1967 |

| Collapsed | August 1, 2007 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 140,000[3] |

| Location | |

| |

Help came immediately from mutual aid in the seven-county Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area and emergency response personnel, charities, and volunteers.[7][8][9] Within a few days of the collapse, the Minnesota Department of Transportation (Mn/DOT) planned its replacement with the I-35W Saint Anthony Falls Bridge. Construction on the replacement bridge was completed quickly, with it opening on September 18, 2008.[10][11]

Location and site history

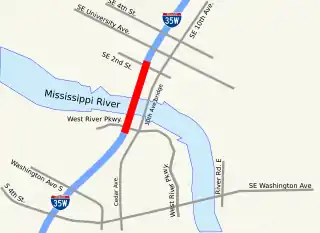

The bridge was located in Minneapolis, Minnesota's largest city and connected the neighborhoods of Downtown East and Marcy-Holmes. The south abutment was northeast of the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, and the north abutment was northwest of the University of Minnesota East Bank campus. The bridge was the southeastern boundary of the "Mississippi Mile" downtown riverfront parkland.[12] Downstream is the 10th Avenue Bridge, once known as the Cedar Avenue Bridge. Immediately upstream is the Saint Anthony Falls lower lock and dam. The first bridge upstream is the historic Stone Arch Bridge, built for the Great Northern Railway and now used for bicycle and pedestrian traffic.[13]

The north foundation pier of the bridge was near a hydroelectric plant that was razed in 1988. The south abutment was in an area polluted by a coal gas processing plant[14][15][16][17] and a facility for storing and processing petroleum products.[15] These uses effectively created a toxic waste site under the bridge, leading to a lawsuit and the removal of the contaminated soil.[14][15][18][19][20] No relationship has been claimed between these previous uses and the bridge failure.

Design and construction

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

The bridge, officially designated "Bridge 9340", was designed by Sverdrup & Parcel to 1961 AASHTO (American Association of State Highway Officials, now American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) standard specifications. The construction contracts, worth in total more than $5.2 million at the time, were initially offered to HurCon Inc. and Industrial Construction Company.[22] HurCon expressed concern about the project, reporting that one portion of the bridge, Pier 6, could not be built as planned. After failed discussions with MnDOT, HurCon backed out of the project altogether.[23]

Construction on the bridge began in 1964 and the structure was completed and opened to traffic in 1967[24][25] during an era of large-scale projects to build the Twin Cities freeway system.[26] When the bridge fell, it was still the most recent river crossing built on a new site in Minneapolis.[27] After the building boom ebbed during the 1970s, infrastructure management shifted toward inspection and maintenance.[26][28]

The bridge's fourteen spans extended 1,907 feet (580 m) long. The three main spans were of deck truss construction while all but two of the eleven approach spans were steel multi-girder construction, the two exceptions being concrete slab construction. The piers were not built in the navigation channel; instead, the center span of the bridge consisted of a single 458-foot (140 m) steel arched truss over the 390-foot (119 m) channel. The two support piers for the main trusses, each with two load-bearing concrete pylons at either side of the center main span, were located on opposite banks of the river.[29][30] The center span was connected to the north and south approaches by shorter spans formed by the same main trusses. Each was 266 feet (81 m) in length, and was connected to the approach spans by a 38-foot (11.6 m) cantilever.[24][31] The two main trusses, one on either side, ranged in depth from 60 feet (18.3 m) above their pier and concrete pylon supports, to 36 feet (11 m) at midspan on the central span and 30 feet (9 m) deep at the outer ends of the adjoining spans. At the top of the main trusses were the deck trusses, 12 feet (3.6 m) in depth and integral with the main trusses.[25] The transverse deck beams, part of the deck truss, rested on top of the main trusses. These deck beams supported longitudinal deck stringers 27 inches (69 cm) in depth, and reinforced-concrete pavement.[25][31] The deck was 113 ft 4 in (34.5 m) in breadth and was split longitudinally. It had transverse expansion joints at the centers and ends of each of the three main spans.[25][32] The roadway deck was approximately 115 feet (35 m) above the water level.[33]

Black ice prevention system

On December 19, 1985, the temperature reached −30 °F (−34 °C). Vehicles coming across the bridge experienced black ice and there was a major pile-up on the bridge on the northbound side. In February and December 1996, the bridge was identified as the single most treacherous cold-weather spot in the Twin Cities freeway system, because of the almost frictionless thin layer of black ice that regularly formed when temperatures dropped below freezing. The bridge's proximity to Saint Anthony Falls contributed significantly to the icing problem and the site was noted for frequent spinouts and collisions.[34][35]

By January 1999, Minnesota DOT began testing magnesium chloride solutions and a mixture of magnesium chloride and a corn-processing byproduct to see whether either would reduce the black ice that appeared on the bridge during the winter months.[36] In October 1999, the state embedded temperature-activated nozzles in the bridge deck to spray the bridge with potassium acetate solution to keep the area free of winter black ice.[37][38] The system came into operation in 2000.[39][40]

Although there were no additional major multi-vehicle collisions after the automated de-icing system was installed, it has been raised as a possibility that the potassium acetate may have contributed to the collapse of the bridge by corroding the structural supports,[41] though the NTSB's final report found that corrosion was not a contributing factor.

Maintenance and inspection

Since 1993, the bridge was inspected annually by MnDOT, although no inspection report was completed in 2007, due to the construction work.[22] In the years prior to the collapse, several reports cited problems with the bridge structure. In 1990, the federal government gave the I-35W bridge a rating of "structurally deficient", citing significant corrosion in its bearings. Approximately 75,000 other U.S. bridges had this classification in 2007.[22][42]

According to a 2001 study by the civil engineering department of the University of Minnesota, cracking had been previously discovered in the cross girders at the end of the approach spans. The main trusses connected to these cross girders and resistance to motion at the connection point bearings was leading to unanticipated out-of-plane distortion of the cross girders and subsequent stress cracking. The situation was addressed prior to the study by drilling the cracks to prevent further propagation[43] and adding support struts to the cross girder to prevent further distortion. The report also noted a concern about lack of redundancy in the main truss system, which meant the bridge had a greater risk of collapse in the event of any single structural failure. Although the report concluded that the bridge should not have any problems with fatigue cracking in the foreseeable future, regular inspection, structural health monitoring, and use of strain gauges had been suggested.[24]

In 2005, the bridge was again rated as "structurally deficient" and in possible need of replacement, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation's National Bridge Inventory database.[44] Problems were noted in two subsequent inspection reports.[45][46] The inspection carried out June 15, 2006 found problems of cracking and fatigue.[46] On August 2, 2007, Governor Tim Pawlenty stated that the bridge had been scheduled to be replaced in 2020.[47]

The I-35W bridge ranked near the bottom of federal inspection ratings nationwide. Bridge inspectors use a sufficiency rating that ranges from the highest score, 100, to the lowest score, zero. In 2005, they rated the bridge at 50, indicating that replacement may have been in order. Out of over 100,000 heavily used bridges, only about 4% scored below 50. On a separate measure, the I-35W bridge was rated "structurally deficient", but was deemed to have met "minimum tolerable limits to be left in place as it is".[45][46][48]

In December 2006, a steel reinforcement project was planned for the bridge. However, the project was canceled in January 2007 in favor of periodic safety inspections, after engineers realized that drilling for the retrofitting would, in fact, weaken the bridge. In internal Mn/DOT documents, bridge officials talked about the possibility of the bridge collapsing, and worried that they might have to condemn it.[49]

The construction taking place in the weeks prior to the collapse included joint work and replacing lighting, concrete and guard rails. At the time of the collapse, four of the eight lanes were closed for resurfacing,[50][51][52][53] and there were 575,000 pounds (261 tonnes) of construction supplies and equipment on the bridge.[54]

Collapse

Bridge as seen from above after the collapse | |

| Date | August 1, 2007 |

|---|---|

| Time | 6:05 p.m. CDT |

| Cause | Failure of gusset plate, design flaw |

| Deaths | 13 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 145 |

_edit.jpg.webp)

At 6:05 p.m. CDT on August 1, 2007, with rush hour bridge traffic moving slowly through the limited number of lanes, the central span of the bridge suddenly gave way, followed by the adjoining spans. The structure and deck collapsed into the river and onto the riverbanks below, the south part toppling 81 feet (25 m) eastward in the process.[55] A total of 111 vehicles[56] were involved, sending their occupants and 18[57] construction workers as far as 115 feet (35 m)[33] down to the river or onto its banks. Northern sections fell into a rail yard, landing on three unoccupied and stationary freight cars.[58][59][60][61]

Sequential images of the collapse were taken by an outdoor security camera located at the parking lot entrance of the control facility for the Lower Saint Anthony Falls Lock and Dam.[62][63] The immediate aftermath of the collapse was also captured by a Mn/DOT traffic camera that was facing away from the bridge during the collapse itself.[64] The federal government immediately launched a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation. NTSB chairman Mark Rosenker, along with a number of investigators, arrived on scene nine hours after the collapse. Rosenker remained in Minneapolis for nearly one week, serving as the government's designated primary interface with federal, state and local officials as well as briefing the press on the status of the investigation.

Mayor R. T. Rybak and Governor Tim Pawlenty declared a state of emergency for the city of Minneapolis[65] and for the State of Minnesota[66] on August 2. Rybak's declaration was approved and extended indefinitely by the Minneapolis City Council the next day.[67] As of the morning following the collapse, according to White House Press Secretary Tony Snow, Minnesota had not requested a federal disaster declaration.[68] President Bush pledged support during a visit to the site on August 4 with Minnesota elected officials and announced that United States Secretary of Transportation (USDOT) Mary Peters would lead the rebuilding effort. Rybak and Pawlenty gave the president detailed requests for aid during a closed-door meeting.[65][69] Local authorities were assisted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) evidence team,[70] and by United States Navy divers who began arriving on August 5.[71]

Victims

Thirteen people were killed.[72] Triage centers at the ends of the bridge routed 50 victims to area hospitals, some in trucks, as ambulances were in short supply.[73] Many of the injured had blunt trauma injuries. Those near the south end were taken to Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC) — those near the north end, to the Fairview University Medical Center and other hospitals. At least 22 children were injured. Thirteen children were treated at Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota,[74] five at HCMC and four or five at North Memorial Medical Center in Robbinsdale, Minnesota.[75] During the first 40 hours, 11 area hospitals treated 98 victims.[74]

Only a few of the vehicles were submerged, but many people were stranded on the collapsed sections of the bridge. Several vehicles caught fire, including a semi-trailer truck, from which the driver's body was later recovered. When fire crews arrived, they had to route hoses from several blocks away.[76][77][78]

A school bus carrying 63 children ended up resting precariously against the guardrail of the collapsed structure, near the burning semi-trailer truck. The children were returning from a field trip to a water park as part of the Waite House Neighborhood Center Day Camp based in the Phillips community. Jeremy Hernandez, a 20-year-old staff member on the bus, assisted many of the children by kicking out the rear emergency exit and escorting or carrying them to safety.[79] One youth worker was severely injured.[80]

Rescue

Civilians immediately took part in the rescue efforts. Minneapolis and Hennepin County received mutual aid from neighboring cities and counties throughout the metropolitan area.[81] The Minneapolis Fire Department (MFD) arrived in six minutes[82] and responded quickly, helping people who were trapped in their vehicles.[83] They took 81 minutes to triage and transport 145 patients with the help of Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC), North Memorial and Allina paramedics. By the next morning, they had shifted their focus to the recovery of bodies, with several vehicles known to be trapped under the debris and several people still unaccounted for. Twenty divers organized by the Hennepin County Sheriff's Office (HCSO) used side-scan sonar to locate vehicles submerged in the murky water. Their efforts were hampered by debris and challenging currents. The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) lowered the river level by two feet (60 cm) downriver at Ford Dam to allow easier access to vehicles in the water.[61][84][85][86] Carl Bolander & Sons, a Saint Paul-based earthworks and demolition company, brought in several cranes and other heavy machinery to assist in clearing debris for rescue workers.

The Minneapolis Fire Department[82] (MFD) created the National Incident Management System command center in the parking lot of the American Red Cross and an adjacent printing company[8] on the west bank. The Minneapolis Police Department (MPD), Minnesota State Patrol and the University of Minnesota Police secured the area, MFD managed the ground operations, and HCSO was in charge of the water operation.[87] The city provided 75 firefighters and 75 law enforcement units.[65]

Rescue of victims stranded on the bridge was complete in three hours.[73] "We had a state bridge, in a county river, between two banks of a city. ... But we didn't have one problem with any of these issues, because we knew who was in charge of the assets," said Rocco Forte, city Emergency Preparedness Director.[8] City, metropolitan area, county and state employees at all levels knew their roles and had practiced them since the city received FEMA emergency management training the year following the September 11, 2001 attacks.[88] Their rapid response time is also credited to the Minnesota and United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) investment in 800 MHz mobile radio communications that were operating in Minneapolis and three of the responding counties,[7][89] the city of Minneapolis collapsed-structures rescue and dive team,[65] and the Emergency Operations Center established at 6:20 p.m. in Minneapolis City Hall.[8][82]

Recovery

Recovery of deceased victims took over three weeks. At the request of the NTSB Chairman Mark Rosenker, the U.S. Navy sent 17 divers and a five-person command-and-control element from its Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit TWO.[71] Divers and Underwater Search Evidence Response Team from the FBI joined the response efforts on August 7, bringing with them truckloads of specialized equipment including FBI-provided side-scan sonar and two submarines.

The Navy Dive team started diving operations in the river at 2 a.m., within hours of arriving, and conducted operations around the clock for the next three weeks, until the recovery portion of the mission was completed. The FBI teams had planned to search with an unmanned submarine, but had to abandon this plan after they found it was too big to maneuver in the debris field and cloudy water. Minneapolis Police Captain Mike Martin stated that, "The public safety divers are trained up to a level where they can kind of pick the low-hanging fruit. They can do the stuff that's easy. The bodies that are in the areas where they can sweep shore to shore, the vehicles that they can get into and search that weren't crushed. They were able to remove some of those. Now what we're looking at is the vehicles that are under the bridge deck and the structural pieces."[91][92]

Seventy-five local, state and federal agencies[87] were involved in the rescue and recovery including emergency personnel and volunteers from the counties of Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Olmsted, Ramsey, Scott, Washington, Winona, and Wright in Minnesota; and St. Croix County, Wisconsin, St. Croix EMS & Rescue Dive Team, and others standing by.[93][94][95] Federal assistance came from the United States Department of Defense, DHS, USACE and the United States Coast Guard. Adventure Divers of Minot, North Dakota, is a private firm who assisted local authorities.[93]

Local businesses donated wireless Internet, ice, drinks and meals for first responders.[96] The Salvation Army canteens served food and water to rescue workers. Teams of officers were sent to hospitals to follow up with the injured, who had been transported to eight different medical facilities.

The Minneapolis Police Chaplain Corps Chaplain Director, Dr. Jeffrey Stewart, arrived and was asked to set up and manage a Family Assistance Center (FAC) for the victims' families. He coordinated site location and staffing arrangements with the city's Department of Health and Family support and relevant Hennepin County offices.[97] When Chaplain Supervisor John LeMay and Lead Chaplain Linda Koelman arrived on the scene, they assisted in setting up the FAC at the Holiday Inn by 8 p.m. As additional Minneapolis Police Chaplains arrived, they began providing services to the victim families, assisting them in locating family members, and providing a calm presence. On August 20, the last victim was recovered from the river.[98]

A Mayo Clinic transport helicopter was standing by at Flying Cloud Airport.[95] The Minnesota National Guard launched a MEDEVAC helicopter and had up to 10,000 guard members ready to help.[87]

As of August 8, 2007, more than 500 Red Cross volunteers and staff persons counseled 2,000 people with grief, trauma, missing persons, and medical issues, and served 7,000 meals to first responders.[99]

Following the initial rescue, Mn/DOT retained Carl Bolander & Sons, an earthworks and demolition contractor of Saint Paul, Minnesota, to remove the collapsed bridge and demolish the remaining spans that did not fall. Divers left the water briefly on August 18 while the company's crew used cranes, excavation drills and cutting torches to remove parts of the bridge deck, beams and girders, hoping to improve access for the divers.[100] After the last person's remains were removed from the wreckage on August 21, the company's crews began dismantling the bridge's remnants.[101] Crews first removed the vehicles stranded on the bridge. By August 18, 80 of the 88 stranded cars and trucks had been moved to the MPD impound lot[102] where owners could claim their vehicles.[100][103] Then workers shifted to removing the bridge deck using cranes and excavators equipped with hoe rams to break the concrete. Structural steel was then disassembled by cranes, and the concrete piers were removed by excavators. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) officials asked demolition crews to use extreme care in removing the bridge remnants to preserve as much of the bridge materials as possible for later analysis. By the end of October 2007, the demolition operation was substantially complete, enabling construction to begin on the new I-35W bridge on November 1, 2007. Much of the bridge debris was temporarily stored at the nearby Bohemian Flats as part of the ongoing investigation of the collapse; it was removed to a storage facility in Afton, Minnesota, in fall 2010.[104] Federal officials planned to bring some of the bridge steel and concrete to the NTSB Material Laboratory in Washington, D.C., for analysis toward determining the cause of the collapse on behalf of FHWA, Mn/DOT and Progressive Construction, Inc. NTSB also interviewed eyewitnesses.[105]

Peters announced that USDOT had granted Minnesota $5 million the day following the collapse.[106] On August 10, Peters announced an additional $5 million "for Minneapolis", or "the state", "to reimburse Minneapolis for increased transit operations to serve commuters in the wake of last week's bridge collapse".[107] U.S. Congress removed the $100 million per-incident cap on emergency appropriations. The United States House of Representatives and United States Senate each voted unanimously for $250 million in emergency funding for Minnesota that President Bush signed into law on August 6.[108][109] On August 10, 2007, Peters announced $50 million in immediate emergency relief, a portion of the overall $250 million,[109][110] which was given to enable "clean-up and recovery work, including clearing debris and re-routing traffic, as well as for design work on a new bridge".[107] "On behalf of Minnesota, we are grateful for all of this help," Pawlenty said.[111]

Investigation

The National Transportation Safety Board immediately began a comprehensive investigation that was expected to take up to eighteen months.[112][113] Immediately following the collapse, Governor Pawlenty and Mn/DOT announced that the Illinois-based engineering firm of Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. had also been selected to provide essential analysis that would parallel the investigation being conducted by the NTSB.[114] One week after the collapse, workers were just beginning to move debris and vehicles to further the process of recovering victims. Cameras and motion detectors were added to the site around the bridge to ward off intruders who, officials said, were hindering the investigation.[115] Hennepin County Sheriff Richard W. Stanek stated, "We are treating this as a crime scene at this point. There's no indication there was any foul play involved, [but] it's a crime scene until we can determine what was the cause of the collapse."[116]

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) built a computer model of the bridge at the Turner Fairbank Highway Research Center in McLean, Virginia.[105] NTSB investigators were particularly interested in learning why a part of the bridge's southern end shifted eastward as it collapsed,[117] but this particular phenomenon was not germane to the ultimate cause of the collapse.[118]

FHWA advised states to inspect the 700 U.S. bridges of similar construction[119] after identifying a possible design flaw related to large steel sheets called gusset plates, which connect girders in the truss structure.[120][118] Officials raised questions as to why such a flaw would not have been discovered in over 40 years of inspections.[118] The flaw was first discovered by Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., an independent consulting firm hired by Mn/DOT to investigate the cause of the collapse.[118]

On January 15, 2008, the NTSB announced it had determined that the bridge's design specified steel gusset plates that were undersized and inadequate to support the intended load of the bridge,[121] a load that had increased over time.[122] This assertion was based on an interim report that calculated the demand-to-capacity ratio for the gusset plates.[121] The NTSB recommended that similar bridge designs be reviewed for this problem.[121][123][124] NTSB Chairman Mark Rosenker said:[6]

Although the Board's investigation is still on-going and no determination of probable cause has been reached, interim findings in the investigation have revealed a safety issue that warrants attention ... During the wreckage recovery, investigators discovered that gusset plates at eight different joint locations in the main center span were fractured. The Board, with assistance from the FHWA, conducted a thorough review of the design of the bridge, with an emphasis on the design of the gusset plates. This review discovered that the original design process of the I-35W bridge led to a serious error in sizing some of the gusset plates in the main truss.

On March 17, 2008, the NTSB announced an update on the investigation relating to load capacity, design issues, computer analysis and modeling, digital image analysis and analysis of the undersized and corroded gusset plates. The investigation revealed that photos from a June 2003 inspection of the bridge showed gusset-plate bowing.[125][126]

On November 13, 2008, the NTSB released the findings of its investigation. The primary cause of the collapse was the undersized gusset plates, at 0.5 inches (13 mm) thick. Contributing to that design or construction error was the fact that 2 inches (51 mm) of concrete had been added to the road surface over the years, increasing the static load by 20%. Another factor was the extraordinary weight of construction equipment and material resting on the bridge just above its weakest point at the time of the collapse. That load was estimated at 578,000 pounds (262 tonnes), consisting of sand, water and vehicles. The NTSB determined that corrosion was not a significant contributor, but that inspectors did not routinely check that safety features were functional.[127]

Claims for compensation

Pawlenty and his office, during the last week of November, announced a "$1 million plan" for the victims. State law has limits that may restrict awards to below that amount. No legislative action was needed for this step. "The administration wanted approval from the Joint House–Senate Subcommittee on Claims as a sign of bipartisan support"—which it received.[128] On May 2, 2008, the state of Minnesota reached a $38 million agreement to compensate victims of the bridge collapse.[129]

In August 2010, the last of the lawsuits against URS Corporation were settled for $52.4 million to avoid prolonged litigation. The cases were handled via a novel consortium of legal entities that worked on a pro-bono basis.[130][131] URS had performed fatigue analysis consulting on the bridge for the Mn/DOT.

The state of Minnesota brought a lawsuit against Jacobs Engineering Group, the successor of Sverdrup & Parcel, the firm that designed the bridge.[132] Jacobs argued too much time had passed since the 1960s design work, but in May 2012, the United States Supreme Court turned down its appeal, allowing the state of Minnesota suit to proceed.[133] Jacobs paid $8.9 million in Nov. 2012 to settle the suit without admitting wrongdoing.[134]

Impacts on business, traffic, and transportation funding

The collapse of the bridge affected river, rail, road, bicycle and pedestrian, and air transit. Pool 1, created by Ford Dam, was closed to river navigation between mile markers 847 and 854.5.[135][136] A rail spur switched by the Minnesota Commercial Railway was blocked by the collapse.[137] The Grand Rounds National Scenic Byway bike path was disrupted as well as two roads, West River Parkway and 2nd Street SE. The 10th Avenue Bridge, which parallels this bridge about a block downstream, was closed to both vehicle and pedestrian traffic until August 31. The Federal Aviation Administration restricted pilots in the 3-nautical-mile (5.6 km) radius of the rescue and recovery.[138]

Thirty-five people lost their jobs when Aggregate Industries of Leicestershire, UK, a company that delivered construction materials by barge, cut production in the area.[139]

Small businesses in metropolitan area counties that were harmed by the bridge collapse could apply beginning August 27, 2007 for loans of up to $1.5 million, at a 4% interest rate for up to a 30-year length, from the U.S. Small Business Administration.[140] The agency's disaster declaration for Hennepin and contiguous counties came two days after Pawlenty's request to the SBA on August 20, 2007.[141] Open for business and unsure they could repay loans, owners near the collapse in some cases lost 25% or 50% of their income. Large retailers in a mall of chain stores lost about the same.[142] As of early January 2008, at least one business closed, one announced it was closing, seven of eight SBA applications had not been approved and merchants continued to explain how they are unable to shoulder more debt.[143]

Seventy percent of the traffic served by the bridge was downtown-bound.[144] Mn/DOT published detour information, and made real-time traffic information available for callers to 5-1-1. The designated alternate route in the area was Trunk Highway 280, which was converted to a temporary controlled-access highway with all at-grade access points closed. Other traffic was diverted to Interstates 694, 494, and 35E. The number of lanes was increased on several of the highways by repainting traffic lines to eliminate wide shoulders, and by widening various "choke-points".

Extra Metro Transit buses were added from park-and-ride locations in the northern suburbs during the rush hours.[145] Abandoned vehicles on I-35W and 280 were towed immediately. On August 6, I-35W was opened to local traffic at the access ramps on each side of the missing section; some on-ramps remained closed.[146]

In the aftermath, pressure was exerted on the state legislature to increase the state fuel tax to provide adequate maintenance funding for Mn/DOT.[147] Ultimately the tax was increased by $0.055 per gallon via an override of Governor Pawlenty's veto of the legislation.[148]

Public events and media

The Minnesota Twins played their home game as scheduled, against the Kansas City Royals at the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome just west of I-35W, on the evening of the accident. Public safety officials told the team that postponing the game could hamper rescue and recovery efforts, since a postponement would send up to 25,000 people back into traffic only blocks from the collapsed bridge. Before the game, a moment of silence was held for the victims of the collapse. The Twins postponed their August 2 game as well as groundbreaking ceremonies for Target Field also located in downtown Minneapolis.[149] The Twins and Minnesota Vikings honored the victims of the collapse by placing a decal of a simulated I-35W shield sign with the date "8-1-07" on the backstop wall within the Metrodome, which was always visible in the typical behind-the-pitcher viewpoint on televised games. The decal remained for the rest of the 2007 season.[150]

The collapse was of interest to national and international news organizations. On the evening of the collapse, CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News Channel stayed live with its coverage during the overnight hours, along with local stations WCCO-AM (830) and KSTP (1500),[151] with most of the coverage in the opening hours coming via satellite from Twin Cities news operations WCCO-TV, KSTP-TV, KMSP-TV, KARE-TV and Minnesota Public Radio. National TV networks sent CBS anchor Katie Couric, NBC's Brian Williams and Matt Lauer, MSNBC's Contessa Brewer, ABC's Charles Gibson, CNN's Soledad O'Brien and Anderson Cooper, and Fox News Channel's Greta Van Susteren and Shepard Smith to broadcast from the Twin Cities.[152] U.S. news organizations interested in national and local bridge safety made a record number of requests for bridge information from Investigative Reporters and Editors, an organization that maintains several databases of federal information. News media made more inquiries for National Bridge Inventory data in the first 24 hours after the Minneapolis bridge collapse than for any previous day in the past 20 years.[153]

Disaster declarations

The Hennepin County Board of Commissioners voted on August 7, 2007 to request that Governor Pawlenty petition President George W. Bush to declare the city of Minneapolis and Hennepin County a major disaster area.[154] About two weeks later, Pawlenty requested major disaster designation on August 20.[155] In a subsequent press release for a separate disaster declaration that month, he said, "Ordinarily, preliminary damage assessments are completed before the emergency disaster declaration is requested."[156] During a press conference and briefing with Bush at the Minneapolis/St.Paul Air Reserve Station base for the 934th Airlift Wing on Tuesday, August 21,[157] Pawlenty estimated the total cost of emergency response at over $8 million including Hennepin County's cost at $7.3 million for rescue and recovery and $1.2 million for other state agencies.[158] He estimated the cost of the collapse to the state at $400,000 to $1 million per day.[159]

That day, Bush gave an emergency rather than major disaster declaration for the state of Minnesota, allowing local and state agencies to recover costs incurred August 1 to 15 from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).[159][160] FEMA can provide payment as required for emergency protective measures (part of FEMA Category B) at no less than 75% federal funding to Hennepin County, the designated county, up to the initial limit of $5 million.[161] Pawlenty planned to ask that the date restriction and monetary cap be lifted.[159] FEMA aid can compensate the county for the saving of lives, protection of public safety and health, and lessening damage to improved property, but not for the disaster-related needs of the victims nor for removing debris and restoration of the bridge and riverfront nor many other categories of needs.[162]

Replacement bridge

The replacement of the collapsed I-35W Mississippi River bridge crosses the Mississippi River at the same location as the original bridge, and carries north–south traffic on I-35W. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule, because of the highway's function as a vital link for carrying commuters and truck freight.[163]

Mn/DOT announced on September 19, 2007, that Flatiron Constructors and Manson Construction Co. would build the replacement bridge for $234 million.[164] The I-35W Saint Anthony Falls Bridge was opened to the public on September 18, 2008, at 5 a.m.[165] Using the innovative design-build project delivery method, the replacement bridge opened over three months ahead of schedule, and was awarded the "Best Overall Design-Build Project Award" for 2009 from the Design-Build Institute of America.[166]

Memorials

Memorial services

About 1,400 people gathered for an interfaith service of healing held at St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral on August 5, 2007, when many of the victims were still missing. Among the presenters were representatives of the Christian, Islamic, Jewish, Hindu, Native American and Hispanic communities, police, fire and emergency responders, the governor, the mayor, a choir and several musicians.[167] Minnesotans held a minute of silence during National Night Out, on August 7, 2007, at 6:05 pm.[168] On August 8, 2007, the Twin Cities chapter of the American Red Cross lowered the flags of the United States, the state of Minnesota and the American Red Cross in remembrance of the victims of the tragedy.[99] Gold Medal Park near the Guthrie Theater was a gathering place for those who wished to leave flowers or remembrances for those who died.[169] During an address to the city council on August 15, 2007, Rybak remembered each of the victims and "the details of their lives".[170]

Memorial garden

The 35W Bridge Remembrance Garden is a memorial commemorating the victims and survivors of the I-35W bridge collapse.[171] The memorial is located off West River Parkway, in Minneapolis.[172] The memorial was revealed to the public on August 1, 2011, the four-year anniversary of the collapse.[172] Minnesota Governor, Mark Dayton and Minneapolis Mayor R. T. Rybak were present, and both spoke at the reveal. The ceremony included reading the names of the 13 victims, followed by a moment of silence held at exactly 6:05 p.m., the time of the collapse four years prior. Afterwards, there was the release of 13 doves in memory of the people who died.[173]

This $900,000 memorial was funded by the Minneapolis Foundation,[174] and the park land was provided by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.[175] The design of the remembrance garden was created by Tom Oslund, alongside survivors and relatives of the victims. [176]

The design was meant to incorporate symbolic natural elements, including:

- Stone, for stability and immortality[177]

- Arborvitae trees, for strength and to live for centuries[177]

- Water, able to purify and regenerate[177]

- Darkness and Light, the transition between tragedy and new life[177]

A prime feature in the garden includes 13 steel I-beam and opaque glass columns. Each column has a name engraved of someone lost, along with their story, some even written in their native language.[177] These 13 columns' linear length totals 81 feet (25 m), signifying the date of the collapse (08/01/07).[172] Behind the 13 columns is a black granite water wall. On the wall, stainless steel words form the quote, "Our lives are not only defined by what happens, but by how we act in the face of it, not only by what life brings us, but by what we bring to life. Selfless actions and compassion create enduring community out of tragic events."[178] Along with the quote, the names of the 171 survivors are etched into the black stone. Another part of the memorial includes a path leading to the bluff, overlooking the Mississippi River and the new I-35W Bridge. At night, the columns, pathway and water wall are illuminated by LED lights.

Musical homage

In May 2008, an orchestral piece composed by Osmo Vänskä titled "The Bridge" was premiered by the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, led by William Schrickel, assistant-principal bassist of the Minnesota Orchestra. Vänskä himself attended the world premiere.[179]

In La Dispute's third studio album, Rooms of The House, several references are made to the disaster, but song "35" describes the event.

2012 memorial

In 2012, installation artist Todd Boss prepared a memorial to the bridge collapse in collaboration with Swedish artist Maja Spasova. The installation was paired with a cycle of 35 poems: "Fragments for the 35W Bridge".[180]

See also

- List of bridge disasters

- List of crossings of the Upper Mississippi River

References

Footnotes

- "BR9340 Construction Plan" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Transportation. 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- "I-35W bridge Fact Sheet". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- "St. Paul–Minneapolis Seven County Area" (Map). 2006 Traffic Volumes (PDF). Street series. Cartography by Office of Transportation Date & Analysis. Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2006. Minneapolis inset. Retrieved August 7, 2007. This map shows average daily traffic volumes for downtown Minneapolis. Trunk highway and Interstate volumes are from 2006.

- Metro Area Street Series Index (PDF) (Map). Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2007. Index map for Mn/DOT's 2006 traffic volumes; relevant maps showing the highest river bridge traffic volumes are Maps 2E, 3E, and 3F.

- Weeks, John A. III (2007). "I-35W Bridge Collapse Myths and Conspiracies". John A. Weeks III. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- Frommer, Frederic J. (November 13, 2008). "NTSB: Design Errors Factor in 2007 Bridge Collapse". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- Schneier, Bruce (August 23, 2007). "Time to Close Gaps in Emergency Communications". Wired News. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Stassen-Berger, Rachel E. & Brewer, John (August 19, 2007). "Planning Paid Off in Bridge Rescues". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, MN. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- "Response to I-35W Bridge Collapse Showed Minneapolis is a City that Works" (Press release). City of Minneapolis. August 15, 2007. Archived from the original on August 29, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- "I-35W St. Anthony Falls Bridge Mississippi River Crossing in Downtown Minneapolis". Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2008. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- "35W Bridge Project". Minnesota Department of Transportation. August 7, 2007. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- Flanagan, Barbara. "Sheba the donkey is off Nicollet Island, but on pictorial map of it", Star Tribune, August 26, 1988, Section:News; page 3B

- "History & Heritage of Civil Engineering". American Society of Civil Engineers. Archived from the original on May 26, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- Meersman, Tom (April 28, 1993). "Citizens Board OKs NSP Plan to Burn Tainted Soil". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 5B.

- Rebuffoni, Dean (December 16, 1991). "Old Plant Site Spawns Environmental, Legal Mess". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 1B.

- Meersman, Tom (March 23, 1993). "Minnegasco Has a Legacy of Waste—to Burn". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 1B.

- Kane, Lucile M. (1987) [1966]. The Falls of St. Anthony: The Waterfall that Built Minneapolis. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Meersman, Tom (July 7, 1993). "Minnegasco Starts Cleaning Up Riverside Waste Today". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 3B.

- Meersman, Tom (March 21, 1996). "The Environment, Digging Up a New Riverside: Minnegasco's Cleanup of Contaminants along the Mississippi Will Clear the Way for a North–South Parkway Link". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 3B.

- Ison, Chris (March 21, 1999). "New Pollution-Agency Chief Was at Center of Cleanup Flap". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 1B.

- Haberman, Clyde (March 3, 2013). "A Disaster Brought Awareness but Little Action on Infrastructure". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- Anderson, G.R. Jr.; Demko, Paul; Hoffman, Kevin; Kaminsky, Jonathan; Smith, Matt & Snyder, Matt (August 9, 2007). "Falling Down". City Pages. 28 (1392). Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- "I-35W bridge had problems during initial construction". Roads & Bridges. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- Fatigue Evaluation of the Deck Truss of Bridge 9340 (PDF) (Report). Minnesota Department of Transportation. March 2001. Report #MN/RC-2001–10 – via Minnesota Local Road Research Board.

- "Interstate 35W Mississippi River Bridge Fact Sheet" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Transportation. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- Cavanaugh, Patricia (October 2006). Politics and Freeways: Building the Twin Cities Interstate System (PDF) (Report). Center for Urban and Regional Affairs and Center for Transportation Studies, University of Minnesota. pp. 1–2. CURA 06-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2007.

- Brandt, Steve (August 7, 2007). "Rangers Describe Bridge Collapse Scene this Afternoon". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007. Since then however several older bridges have been replaced.

- Petroski, Henry (August 4, 2007). "Learning from Bridge Failure: Collapses Such as the I-35W in Minneapolis Give Engineers the Best Clues about What Not to Do. Let's Hope the Lessons Are Remembered". Los Angeles Times (Op-Ed).

- "At Least 7 Dead in I-35 Bridge Collapse". Minneapolis: WCCO-TV. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- "U.S. Officials Urge Quick Inspections of Bridges Similar to Minneapolis Span". Montreal: CJAD-AM. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009.

- Fatigue Evaluation and Redundancy Analysis, Bridge 9340 I-35W over Mississippi River (PDF) (Draft Report). Minnesota Department of Transportation. 2006. pp. 1.1–1.3. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2007.. These contract plans contain dimensions and elevations at Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

- "35W bridge collapse: fact sheet". Science Buzz: What Caused the 35W Bridge to Collapse?. Science Museum of Minnesota. 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- "Construction Plan for Bridge No. 9340" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Transportation. June 18, 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007. Sheets 1 and 86 of these plans (pp. 2 and 87) show a finished grade profile at an elevation of approximately 840 feet (260 m) over the main span, which is 115 feet (35 m) over the pool elevation of 725 feet (221 m). This is consistent with a later inspection report, Bridge Inspection Report Bridge No. 9340 Archived August 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, published online by Minnesota Department of Transportation in 2007. The Road Inventory Bridge Sheet (p. 4) shows a height of 132 feet (40 m) from river bottom to superstructure and a river depth of 15 feet (4.6 m), correlating to a height of 117 feet (36 m) over the water.

- Blake, Laurie (February 3, 1996). "February Deep Freeze: Black Ice Makes I-35W Bridge Treacherous". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 10A. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012 – via Highbeam Research.

- von Sternberg, Bob (December 27, 1996). "Minnesota Is One Big Deep Freeze: What Is the Sound of a Cold Record Shattering? It's the Sound of Silence from Dead Motors, of Crumpling Metal on Icy Roads, of Resigned Grumbling. But Take Heart—It Will Warm Up". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 1A.

- Blake, Laurie (January 21, 1999). "State Hopes to Speed Up North-Metro Lane Project: But It Clashes with Met Council over Whether Addition to Interstate Should Be for Car Pools". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 2B.

- Blake, Laurie (October 19, 1999). "I-35W Bridge Getting De-Icer System: Unit Will Target Ice Before It Can Form". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 1A.

- "I-35W & Mississippi River Bridge Anti-Icing Project" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2011.

- Blake, Laurie (January 13, 2000). "Met Council Will Survey Our Citizens' Travel Habits: Study Will Include Trip Numbers and Times, Speed of Drivers and Waits at Ramp Meters". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 2B.

- Blake, Laurie (February 3, 2000). "Richfield May Face Traffic Challenges: How Will I-494 Accommodate Best Buy's 5,000 Commuters?". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. 2B..

- "De-Icing Chemical May Have Corroded 35W Bridge". Minneapolis: WCCO-TV. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- Cohen, Sharon & Bakst, Brian (August 2, 2007). "Minn. Bridge Problems Uncovered in 1990". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- When a crack forms in a metal structure, holes (called "drill stops", "stop holes", or "crack arrest holes") are sometimes drilled at the ends of the crack in order to spread the stress that is causing the crack and thus prevent the crack from spreading. See, for example: Sanati, Laurence (2015) "Improved guidelines for the drill stop-hole retrofit method of steel structures," M.S. thesis (Civil Engineering: Structural engineering), California State University (Sacramento, California). Available on-line at: Sacramento State Scholarworks

- "Hopes Dim in Minneapolis for Survivors". MyWay. Associated Press. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- Bridge Inspection Report 06–10–05 (PDF) (Report). Minnesota Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2007.

- Bridge Inspection Report 06–15–06 (PDF) (Report). Minnesota Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2007.

- Pawlenty, Tim. "Interview With Minn. Gov Pawlenty". Hannity & Colmes (Interview). Interviewed by Sean Hannity. Fox News – via Real Clear Politics.

- Dedman, Bill (August 3, 2007). "I-35 Bridge Was Rated among the Nation's Worst". NBC News. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- "Phone Call Put Brakes on Bridge Repair". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. August 20, 2007. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- "35W Bridge Collapses". Golden Valley, MN: KARE-TV. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "I-35W Will Narrow to One Lane in Minneapolis over Two Nights, July 31 and August 1" (Press release). Minnesota Department of Transportation. July 31, 2007. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "Fifth Body Recovered After Bridge Collapse". ABC News. August 3, 2007.

- Van Hampton, Tudor (August 6, 2007). "NTSB: Bridge Contractor Had Prior I-35W Experience". Engineering News Record.

- Hoppin, Jason (August 23, 2007). "Bridge Probe Turns to Anti-Ice System". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, MN. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- Stachura, Sue (August 5, 2007). "Northern End of I-35W Bridge Is Now Focus of Probe". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- Highway Accident Report: Executive Summary (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. November 14, 2008. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Survivors Describe Terror as Bridge Collapsed". CNN. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on August 2, 2007.

- "I-35W Bridge Collapses". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007.

- "35W Bridge over Mississippi Collapsed". St. Paul, MN: KSTP-TV. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "Investigators in Bridge Collapse Focus on Chilling Video". Chicago Tribune. August 2, 2007.

- "Corps Adjusts River Level to Ease Recovery Efforts". Star Tribune. Minneapolise. August 3, 2007. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- "Video Captures Bridge Collapse". CNN. August 2, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- "CNN Gets Beat on Video of Collapse". Washington, DC: WTOP-FM. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- "Camera Captures Bridge Moments after Collapse". Golden Valley, MN: KARE-TV. August 8, 2007

- "Governor Pawlenty Declares Peacetime Emergency, Activates State Emergency Operations Center" (Press release). Office of the Governor of Minnesota. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- "Minneapolis City Council Official Proceedings (Resolution 2007R-418)" (PDF). City of Minneapolis. August 3, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- "Latest on Deadly Minneapolis Bridge Collapse". On Deadline. USA Today. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Williams, Brandt (August 4, 2007). "Bush Surveys Collapsed Minnesota Bridge, Pledges to Help Cut Red Tape in Rebuilding". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- "Transcripts". CNN. August 7, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Merriam, Elizabeth (August 8, 2007). "MDSU-2 Arrives in Minneapolis Prepared to Help" (Press release). Fleet Public Affairs Center Atlantic, United States Navy. NNS070808-04. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "Remembering the Dead". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Pelsuo, Paul (August 24, 2007). "Minneapolis Assistant Chief Speaks about Bridge Collapse at FRI". Firehouse.com News. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Thompson, Cheryl A. (August 17, 2007). "Calm, Steady Hospital Care Shines During Bridge Disaster". Minnesota Hospital Association. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012; Mador, Jessica (August 2, 2007). "Many Still Missing". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- "Governor Orders Inspection of All Minn. Bridges". Los Angeles: KCBS-TV. CBS News. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "Freeway Bridge Collapses into River During Rush Hour in Minneapolis". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. August 2, 2007.

- "Minneapolis Bridge Collapses, Seven Dead". The Age. Melbourne. August 1, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Peiken, Matt (August 7, 2007). "Paul Eickstadt". Minnesota Public Radio.

- Barry, Ellen (August 3, 2007). "Stunned Victim Turns Hero". The New York Times.

- "School Kids on Crashed Bus Reunited with Families". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007.

- "Vignettes from Minn. Bridge Collapse". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008; "Hennepin County Staff Report to Board on Efforts Surrounding Bridge Collapse". Hennepin County, Minnesota. August 10, 2007. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- Roy, Sandy Colvin (August 20, 2007). "Guest Column: Planning Helped Minneapolis Respond to Bridge Collapse". Nation's Cities Weekly. 30 (33). Archived from the original on April 9, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Reichardt, Carson J. S. (August 1, 2022). "Ankeny fire chief remembers Minneapolis bridge collapse on its 15th anniversary: James Clack started working for the Minneapolis Fire Department in 1986 before leaving in 2008". We Are Iowa. West Des Moines, Iowa. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- "Divers Searching for Victims in Bridge Collapse". Orange County Register. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- Rucker, Philip & Branigin, William (August 3, 2007). "Difficult Conditions Hamper River Search". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Horwich, Jeff (August 2, 2007). "Recovery Effort Cautious, Deliberate". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- Lee, Christopher & Lewis, Paul (August 3, 2007). "With Minor Exceptions, System Worked". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 25, 2007; Kyle, Susan Nicol (August 3, 2007). "Disaster Training Pays Off in Minneapolis". Firehouse.com News. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- Belton, Sharon Sayles (November 8, 2001). "Minneapolis 2002 Budget Address". City of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2007; "Past Community Specific Programs". Federal Emergency Management Agency. November 16, 2006. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- "County Board Actions: Hennepin Accepts Grants for Emergency Equipment and Training, 800 MHz Radio Projects". Hennepin County, Minnesota. September 14, 2004. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- "Navy Divers Join US Bridge Effort". BBC News. August 7, 2007.

- "Feds: Construction Equipment Weight May Be Factor". Minneapolis: WCCO. August 8, 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- "Sheriff Announces Recovery of Last Known Victim, Cites Team Effort". Hennepin County, Minnesota. August 20, 2007. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- "Rochester-Area Professionals, Residents Offer to Help". Post-Bulletin. Rochester, MN. August 3, 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2007; "Update: Contractor Says Workers 'Rode the Bridge Down'". St. Cloud Times. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Nienaber, Dan (August 2, 2007). "Locals Stand By to Assist in Bridge Disaster". Mankato Free Press. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013.

- Bruch, Michelle & O'Regan, Mary (August 20, 2007). "Lending a Hand". Downtown Journal; Arnoldy, Ben (August 8, 2007). "Minneapolis Shows Why It's Rated No. 1 in Volunteerism". The Christian Science Monitor; "New Wi-Fi Network Proves Critical in Minneapolis Bridge Disaster". Computerworld. August 3, 2007. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- U.S. Fire Administration/Technical Report Series I-35W Bridge Collapse and Response Minneapolis, Minnesota USFA-TR-166/August 2007, page 18

- A Newsletter of the Police Executive Research Forum, Vol. 21, No. 10 | October 2007, Minneapolis Area Police Officials Describe, "Lessons Learned" from Bridge Collapse

- "Flags Lowered to Half Staff at Red Cross Headquarters" (Press release). American Red Cross Twin Cities Area Chapter. August 8, 2007. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Brown, Curt & Chanen, David (August 18, 2007). "Search Continues for Last Bridge Collapse Victims". Post-Bulletin. Rochester, MN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- "Bush Declares Emergency, Debris Removal Begins". Minneapolis: WCCO-TV. Associated Press. August 21, 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- "Recovering Vehicles and Property from 35W Bridge". City of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on September 21, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2007.

- "Interstate 35W Bridge Collapse". Minnesota Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on August 30, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- "35W Bridge Parts Moved From Bohemian Flats". Saint Paul, MN: KSTP-TV. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- "NTSB Continues to Investigate Minneapolis Bridge Collapse". Southwest Nebraska News. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2007.

- "U.S. Secretary of Transportation Mary Peters Announces US$5 Million in Immediate Funding During Visit to Downed I-35 Bridge in Minneapolis" (Press release). Federal Highway Administration. August 2, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007; Davey, Monica (August 3, 2007). "At Bridge Site, Search of River Moves Slowly". The New York Times.

- Echols, Sara (August 10, 2007). "U.S. Secretary of Transportation Mary Peters Announces US$50 Million in Immediate Emergency Relief for Minneapolis; US$5 Million for Transit" (Press release). United States Department of Transportation. DOT 81-07. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Diaz, Kevin (August 3, 2007). "Congress Puts Finishing Touches on $250 Million Emergency Rebuild Package". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- Horwath, Justin (August 8, 2007). "Federal, State Politicians Hasten to Help". University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Minneapolis: The Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- "Transportation Secretary Announces Release of Some Federal Money ..." Bismarck, ND: KXMB-TV. Associated Press. August 10, 2007. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

Stations: clarifies that the $50 million is downpayment on $250 million authorized by Congress

- "Update: Divers Recover Another Body from Bridge Rubble". The St. Cloud Times. Associated Press. August 10, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

- "What Went Wrong? NTSB Begins Probe of Bridge Collapse". CNN. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Moylan, Martin (August 8, 2007). "NTSB Sleuths Responsible for Finding Out Why the Bridge Collapsed". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- Kaszuba, Mike (December 20, 2007). "MnDOT to face another inquiry". Star Tribune. Minneapolis.

- "Police Arrest Intruders near Fallen Bridge, Boost Security". CNN. August 8, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- Kress, Rory (August 3, 2007). "'Their Entire World's Come Unhinged'". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- Jackson, Henry C. "Minn. Bridge Toll Far Less than Feared". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Davey, Monica & Wald, Matthew L. (August 8, 2007). "Potential Flaw Is Found in Design of Fallen Bridge". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- Grossman, Ian. "U.S. Secretary of Transportation Mary E. Peters Calls on States to Immediately Inspect All Steel Arch Truss Bridges" (Press release). Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011.

- "Update on NTSB Investigation of Collapse of I-35W Bride in Minneapolis" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. August 8, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- Holt, Reggie & Hartmann, Joseph (January 11, 2008). Adequacy of the U10 & L11 Gusset Plate Designs for the Minnesota Bridge No. 9340 (I-35W over the Mississippi River) (PDF) (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Cambridge Systematics (June 2006). "Minnesota Truck Size and Weight Project" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Transportation. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Walsh, Paul (January 15, 2008). "Bridge collapse: A half-inch closer to why". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- "Safety Recommendation H-08-1" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. January 15, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Williams, Terry (March 17, 2008). "Fifth Update: Investigation into Collapse of I-35 Bridge" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009.

- Kennedy, Tony (March 23, 2008). "Old Photos Show Flaws in Steel of I-35W bridge". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on March 24, 2008.

- Stachura, Sea (November 12, 2008). "Despite Final NTSB Report, Some Still Have Questions". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- Lohn, Martiga (November 29, 2007). "Emergency Aid Approved for Minnesota Bridge Collapse Victims". The Dickinson Press. Associated Press. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- Lohn, Martiga (May 2, 2008). "Minnesota Inks Deal with Bridge Victims". CBS News. Associated Press. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- Qualters, Sheri (August 26, 2010). "Q&A: Pro Bono Consortium of 17 Firms Led to Settlement over Minneapolis Bridge Collapse". Law.com.

- James, Frank (August 23, 2010). "Last Minneapolis Bridge Collapse Lawsuit Settled For $52.4 Million". NPR. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- Melo, Frederick (August 1, 2011). "Four Years after I-35W Bridge Collapse, a Community Remembers Disaster's Victims". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, MN.

- "Supreme Court Lets State's Claims Go Forward Against Design Firm in Minn. Bridge Collapse". The Washington Post. Associated Press. May 29, 2012. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- "Minn. Settles last case in I-35W bridge disaster".

- "Coast Guard Responds to Minnesota Interstate Bridge Collapse" (Press release). United States Coast Guard. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- "Verbal Confirmation of Correct Mile Markers from USCG Personnel". United States Coast Guard. August 3, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Dulek, Amber (August 3, 2007). "Bridge Collapse Unlikely to Affect River Traffic". Winona Daily News. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- "NOTAM Number: FDC 7/0805". Federal Aviation Administration. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007; "NOTAM Number: FDC 7/2010". Federal Aviation Administration. August 9, 2007. Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Wyant, Carrissa (September 10, 2007). "Bridge Collapse Forces Layoffs". Minneapolis / St. Paul Business Journal. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Wyant, Carissa (August 24, 2007). "SBA Offers Loans for Businesses Affected by Bridge Collapse". Minneapolis / St. Paul Business Journal. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- "SBA Offers Disaster Assistance to Minnesota Businesses Economically Affected by the Collapse of Interstate 35W Bridge" (Press release). PRNewswire-USNewswire. August 24, 2007. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2007 – via Yahoo! News. Preston, Steven C. (August 22, 2007). "Disaster Declaration #10991" (PDF). Small Business Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- Anderson, G.R. Jr. (September 5, 2007). "Economy in Freefall". City Pages. 28 (1396). Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Cormany, Diane L. (January 4, 2008). "Small Retailers Struggle to Survive Bridge Collapse". MinnPost. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- Stiles, Ed (August 3, 2007). "UA Engineers to Help Ease Traffic Woes Following Minneapolis Interstate Bridge Collapse". UA News. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Transit Alternatives to I-35W". Minneapolis: WCCO-TV. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- "Mn/DOT to Further Open Northbound, Southbound I-35W Openings to Improve Traffic Flow and Local Access" (Press release). Minnesota Department of Transportation. August 5, 2007. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- Morrissey, Ed (January 15, 2008). "Bridge Collapse Caused by Design Flaw, Not Maintenance". Captains's Quarters. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- Weber, Tom (April 1, 2008). "State's Gas Tax Goes Up Today". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- "Twins Postpone Thursday's Game after Bridge Collapses near Metrodome". ESPN. ESPN.com News Services. August 1, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- Campbell, Dave (August 3, 2007). "Twins Back at It, with Bridge on Minds". USA Today.

- Ariens, Chris (August 1, 2007). "Bridge Collapse: Cable Net Coverage". TV Newser. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- Preston, Rohan (August 2, 2007). "Disaster Draws Biggest Names in News Media to Twin Cities". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Strupp, Joe (August 3, 2007). "IRE Gets Most Inquiries Ever for Bridge Data". Editor & Publisher. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- "County Board Asks Governor to Declare Hennepin a Disaster Area". Hennepin County, Minnesota. August 7, 2007. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Condon, Patrick (August 21, 2007). "Bush Approves More Bridge Collapse Aid". Philly Online. Associated Press.

- "Governor Pawlenty, Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff Announce Presidential Disaster Declaration for Three Counties Impacted by Flooding" (Press release). Office of the Governor of Minnesota. August 23, 2007. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Feller, Ben (August 21, 2007). "Bush Updated on Bridge Collapse". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- Vezner, Tad (August 21, 2007). "35W Bridge Collapse / 13th, Final Victim Recovered". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, MN. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- Hoppin, Jason (August 21, 2007). "Recovery Ends, Rebuilding Begins". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, MN. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- "Statement on Federal Disaster Assistance for Minnesota" (Press release). The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. August 21, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007; "President Declares Emergency Federal Aid for Minnesota" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. August 21, 2007. HQ-07-168. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- "Federal Aid Programs for Minnesota Emergency Disaster Recovery" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. August 21, 2007. HQ-07-168FactSheet. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2007; "Designated Counties for Minnesota Bridge Collapse, Disaster Summary For FEMA-3278-EM, Minnesota". Federal Emergency Management Agency. August 21, 2007. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- "Appendix A, Applicant Handbook, FEMA 323". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Scheck, Tom (August 7, 2007). "Rebuild May Begin in September". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- Lohn, Martiga (September 19, 2007). "Rich Contract Awarded for I-35W Bridge Replacement". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Gutknecht, Kevin (September 15, 2008). "Mn/DOT to Open I-35W St. Anthony Falls Bridge to Traffic at 5 a.m. Thursday, Sept. 18" (Press release). Minnesota Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008.

- "2009 Design-Build Award Competition Winners". Design-Build Institute of America. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Martin, Rachel (August 6, 2007). "Minneapolis Holds Prayer Service for Bridge Victims". NPR. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- Hult, Karla (August 8, 2007). "National Night Out Turns into Moment of Remembrance". Golden Valley, MN: KARE-TV. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013.

- Metzger, Michael; Thomas, Dylan (August 20, 2007). "Making Memorials". Downtown Journal. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- VanDerVeen, Kari (August 20, 2007). "Mayor Calls for Special Legislative Session". Downtown Journal. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- "Interstate 35W Bridge in Minneapolis". Minnesota Department of Transportation.

- Stocks, Anissa. "Park Board Approves Site for I-35W Bridge Memorial". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- "I-35W Bridge Collapse Memorial to Be Dedicated". StarTribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- "35W Remembrance Garden Fund". Minneapolis Foundation. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- "Work Begins on Remembrance Garden for I-35W Bridge Collapse Victims". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- Berg, Steve. "In New Setting along the River, Remembrance Garden Will Command More Visibility, More Meaning". MinnPost. Minneapolis. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "I-35W Bridge Remembrance Garden". Oslund and Associates. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014.

- Olson, Dan. "Hundreds Turn Out to Dedication of 35W Bridge Memorial". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- Combs, Marianne (May 16, 2008). "Osmo Vanska composes a musical 'bridge'". MPR News. Minneapolis. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "Readers' I-35W bridge poems inspire". Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 3, 2012.

Works cited

- Costello, Mary Charlotte (2002). Climbing the Mississippi River Bridge by Bridge, Volume Two: Minnesota. Cambridge, MN: Adventure Publications. ISBN 978-0-9644518-2-7.

- "Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, as amended, and Related Authorities" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Rofidal, Kevin (2007). "Twin Cities Tragedy: Coast Guard Responds Following the Collapse of the I-35W Bridge in Minneapolis" (PDF). USCG Reservist. 54 (7–07): 26–29. Retrieved September 17, 2008 – via Wikimedia Commons.

Further reading

- Nunnally, Patrick, ed. (2011). The City, the River, the Bridge: Before and After the Minneapolis Bridge Collapse. University of Minnesota Press; studies by civil engineers, geographers, and others on the events and aftermath of the collapse of the bridge

- Minmao Liao & Taichiro Okazaki (2009). A Computational Study of the I-35W Bridge Collapse (Report). Center for Transportation Studies, University of Minnesota.

External links

- Collapse of I-35W Highway Bridge Minneapolis, Minnesota, Official report by the National Transportation Safety Board

- Interstate 35W Bridge in Minneapolis, Minnesota Department of Transportation

- Scientific perspectives on the collapse – from the Science Museum of Minnesota

- Minnesota Historical Society: 35W Bridge Resources

- U.S. Bridge Information – New AASHTO Bridge Information Web Site

- NTSB Docket Management System for Bridge Collapse Investigation Documents

- Radio breaking news and coverage (airchecks) of the 35W bridge collapse From radiotapes.com.

- OxBlue Construction Camera and time-lapse footage of reconstruction Archived February 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- 13 Seconds in August – A project by the Star Tribune (Flash Player required)