Ice shelf

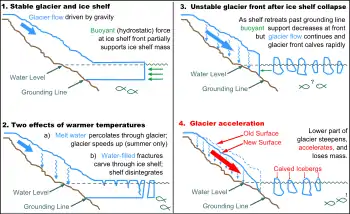

An ice shelf is a large floating platform of ice that forms where a glacier or ice sheet flows down to a coastline and onto the ocean surface. Ice shelves are only found in Antarctica, Greenland, Northern Canada, and the Russian Arctic. The boundary between the floating ice shelf and the anchor ice (resting on bedrock) that feeds it is the grounding line. The thickness of ice shelves can range from about 100 m (330 ft) to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).

In contrast, sea ice is formed on water, is much thinner (typically less than 3 m (9.8 ft)), and forms throughout the Arctic Ocean. It is also found in the Southern Ocean around the continent of Antarctica.

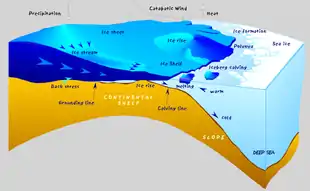

The movement of ice shelves is principally driven by gravity-induced pressure from the grounded ice.[1] That flow continually moves ice from the grounding line to the seaward front of the shelf. In steady state, about half of Antarctica's ice shelf mass is lost to basal melt and half is lost to calving, but the relative importance of each process varies significantly between ice shelves.[2][3] In recent decades, Antarctica's ice shelves have been out of balance, as they have lost more mass to basal melt and calving than has been replenished by the influx of new ice and snow.[4]

Typically, a shelf front will extend forward for years or decades between major calving events. Snow accumulation on the upper surface and melting from the lower surface are also important to the mass balance of an ice shelf. Ice may also accrete onto the underside of the shelf.

The density contrast between glacial ice and liquid water means that at least 1/9 of the floating ice is above the ocean surface, depending on how much pressurized air is contained in the bubbles within the glacial ice, stemming from compressed snow. The formula for the denominators above is , density of cold seawater is about 1028 kg/m3 and that of glacial ice from about 850 kg/m3[5][6] to well below 920 kg/m3, the limit for very cold ice without bubbles.[7][8] The height of the shelf above the sea can be even larger, if there is much less dense firn and snow above the glacier ice.

The world's largest ice shelves are the Ross Ice Shelf and the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

The term captured ice shelf has been used for the ice over a subglacial lake, such as Lake Vostok.

Canadian ice shelves

All Canadian ice shelves are attached to Ellesmere Island and lie north of 82°N. Ice shelves that are still in existence are the Alfred Ernest Ice Shelf, Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, Milne Ice Shelf and Smith Ice Shelf. The M'Clintock Ice Shelf broke up from 1963 to 1966; the Ayles Ice Shelf broke up in 2005; and the Markham Ice Shelf broke up in 2008. The remaining ice shelves have also lost a significant amount of their area over time, with the Milne Ice Shelf being the last to be affected, with it breaking off in August 2020.

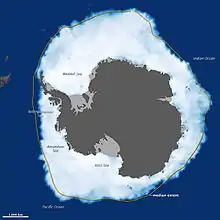

Antarctic ice shelves

A large portion of the Antarctic coastline has ice shelves attached.[9] Their aggregate area is over 1,550,000 square kilometers (600,000 square miles).[10]

Russian ice shelves

The Matusevich Ice Shelf was a 222 square kilometers (86 square miles) ice shelf located in Severnaya Zemlya being fed by some of the largest ice caps on October Revolution Island, the Karpinsky Ice Cap to the south and the Rusanov Ice Cap to the north.[11] In 2012 it ceased to exist.[12]

Ice shelf disruption

In the last several decades, glaciologists have observed consistent decreases in ice shelf extent through melt, calving, and complete disintegration of some shelves.[13]

The Ellesmere ice shelf was reduced by 90% in the twentieth century, leaving the separate Alfred Ernest, Ayles, Milne, Ward Hunt, and Markham ice shelves. A 1986 survey of Canadian ice shelves found that 48 km2 (3.3 cubic kilometres) of ice calved from the Milne and Ayles ice shelves between 1959 and 1974.[14] The Ayles Ice Shelf calved entirely on August 13, 2005. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, the largest remaining section of thick (>10 meters (33 feet)) landfast sea ice along the northern coastline of Ellesmere Island, lost 600 square kilometers (230 square miles) of ice in a massive calving in 1961–1962.[15] It further decreased by 27% in thickness (13 meters (43 feet)) between 1967 and 1999.[16] In summer 2002, the Ward Ice Shelf experienced another major breakup,[17] and other instances of note happened in 2008 and 2010 as well.[18] The last remnant to remain mostly intact, the Milne Ice Shelf, also ultimately experienced a major breakup at the end of July 2020, losing over 40% of its area.[19]

Two sections of Antarctica's Larsen Ice Shelf broke apart into hundreds of unusually small fragments (hundreds of meters wide or less) in 1995 and 2002, Larsen C calved a huge ice island in 2017.[20]

Recent observations indicate that a portion of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet that holds back Thwaites Glacier is now showing instability, as warming waters undermine the grounding zone.[21][22] According to Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder and a leader of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, in a 2021 interview from McMurdo Station, “Things are evolving really rapidly here. It’s daunting.”[22]

The breakup events may be linked to the dramatic polar warming trends that are part of global warming. The leading ideas involve enhanced ice fracturing due to surface meltwater and enhanced bottom melting due to warmer ocean water circulating under the floating ice.

The cold, fresh water produced by melting underneath the Ross and Filchner-Ronne ice shelves is a component of Antarctic bottom water.

Although it is believed that the melting of floating ice shelves will not raise sea levels, technically, there is a small effect because seawater is ~2.6% more dense than fresh water combined with the fact that ice shelves are overwhelmingly "fresh" (having virtually no salinity); this causes the volume of the seawater needed to displace a floating ice shelf to be slightly less than the volume of the fresh water contained in the floating ice. Therefore, when a mass of floating ice melts, sea levels will increase; however, this effect is small enough that if all extant sea ice and floating ice shelves were to melt, the corresponding sea level rise is estimated to be ~4 centimeters (1.6 inches).[23][24][25]

See also

- Ice-sheet dynamics

References

- Greve, R.; Blatter, H. (2009). Dynamics of Ice Sheets and Glaciers. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03415-2. ISBN 978-3-642-03414-5.

- Rignot, E.; Jacobs, S.; Mouginot, J.; Scheuchl, B. (19 July 2013). "Ice-Shelf Melting Around Antarctica". Science. 341 (6143): 266–270. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..266R. doi:10.1126/science.1235798. PMID 23765278. S2CID 206548095.

- Depoorter, M. A.; Bamber, J. L.; Griggs, J. A.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; Ligtenberg, S. R. M.; van den Broeke, M. R.; Moholdt, G. (3 October 2013). "Calving fluxes and basal melt rates of Antarctic ice shelves". Nature. 502 (7469): 89–92. Bibcode:2013Natur.502...89D. doi:10.1038/nature12567. PMID 24037377. S2CID 4462940.

- Greene, Chad A.; Gardner, Alex S.; Schlegel, Nicole-Jeanne; Fraser, Alexander D. (10 August 2022). "Antarctic calving loss rivals ice-shelf thinning". Nature. 609 (7929): 948–953. Bibcode:2022Natur.609..948G. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05037-w. PMID 35948639. S2CID 251495070.

- Pidwirny, Michael (2006). "Glacial Processes". www.physicalgeography.net. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- Shumskiy, P. A. (1960). "Density of Glacier Ice". Journal of Glaciology. 3 (27): 568–573. Bibcode:1960JGlac...3..568S. doi:10.3189/S0022143000023686. ISSN 0022-1430.

- "Densification". www.iceandclimate.nbi.ku.dk. 2009-09-11. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- "Ice – Thermal Properties". www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- Bindschadler, R.; Choi, H.; Wichlacz, A.; Bingham, R.; Bohlander, J.; Brunt, K.; Corr, H.; Drews, R.; Fricker, H. (2011-07-18). "Getting around Antarctica: new high-resolution mappings of the grounded and freely-floating boundaries of the Antarctic ice sheet created for the International Polar Year". The Cryosphere. 5 (3): 569–588. Bibcode:2011TCry....5..569B. doi:10.5194/tc-5-569-2011. hdl:2060/20120010397. ISSN 1994-0424. S2CID 52888670.

- Depoorter, M. A.; Bamber, J. L.; Griggs, J. A.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; Ligtenberg, S. R. M.; van den Broeke, M. R.; Moholdt, G. (2013-10-03). "Calving fluxes and basal melt rates of Antarctic ice shelves". Nature. 502 (7469): 89–92. Bibcode:2013Natur.502...89D. doi:10.1038/nature12567. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 24037377. S2CID 4462940.

- Mark Nuttall, Encyclopedia of the Arctic, p. 1887

- Willis, Michael J.; Melkonian, Andrew K.; Pritchard, Matthew E. (2015-10-01). "Outlet glacier response to the 2012 collapse of the Matusevich Ice Shelf, Severnaya Zemlya, Russian Arctic". Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. 120 (10): 2015JF003544. Bibcode:2015JGRF..120.2040W. doi:10.1002/2015JF003544. ISSN 2169-9011.

- "Antarctic ice shelf 'hanging by thread': European scientists". July 10, 2008. Yahoo! News.

- Jeffries, Martin O.Ice Island Calvings and Ice Shelf Changes, Milne Ice Shelf and Ayles Ice Shelf, Ellesmere Island, N.W.T.. Arctic 39 (1) (March 1986)

- Hattersley-Smith, G. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf: recent changes of the ice front. Journal of Glaciology 4:415–424. 1963.

- Vincent, W.F., J.A.E. Gibson, M.O. Jeffries. Ice-shelf collapse, climate change, and habitat loss in the Canadian high Arctic. Polar Record 37 (201): 133–142 (2001)

- NASA Earth Observatory (2004-01-20). "Breakup of the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf".

- Canada, Environment and Climate Change (2010-12-17). "Ward Hunt ice shelf calving – Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- "Canada's last fully intact Arctic ice shelf collapses". Reuters. 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- Kropshofer, Katharina (2017-10-09). "Scientists hope damage to Larsen C ice shelf will reveal ecosystems". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- "The Threat from Thwaites: The Retreat of Antarctica's Riskiest Glacier" (Press release). Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES). University of Colorado Boulder. 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2021-12-14.

- Kaplan, Sarah (December 13, 2021). "Crucial Antarctic ice shelf could fail within five years, scientists say". The Washington Post. Washington DC. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- "Melting of Floating Ice Will Raise Sea Level". physorg.com. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Noerdlinger, P.D.; Brower, K.R. (July 2007). "The melting of floating ice raises the ocean level". Geophysical Journal International. 170 (1): 145–150. Bibcode:2007GeoJI.170..145N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03472.x.

- Jenkins, A.; Holland, D. (August 2007). "Melting of floating ice and sea level rise". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (16): L16609. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3416609J. doi:10.1029/2007GL030784.

External links

- Further information from the Australian Antarctic Division Archived 2017-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- http://nsidc.org/quickfacts/iceshelves.html Archived 2010-06-15 at the Wayback Machine – from the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center

- https://web.archive.org/web/20170801182746/http://ice-glaces.ec.gc.ca/ – from the Canadian Ice Service