Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, more commonly known as The Iditarod, is an annual long-distance sled dog race run in early March. It travels from Anchorage to Nome, entirely within the US state of Alaska. Mushers and a team of between 12 and 14 dogs,[1] of which at least 5[2] must be on the towline at the finish line, cover the distance in 8–15 days or more.[1] The Iditarod began in 1973 as an event to test the best sled dog mushers and teams but evolved into today's highly competitive race.

| Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race | |

|---|---|

| Date | March |

| Location | Anchorage to Nome, Alaska, United States |

| Event type | Sled Dog Race |

| Distance | 938 mi (1,510 km) |

| Established | 1973 |

| Course records | Dallas Seavey, 7 d 14h 8m 57s (2021) |

| Official site | iditarod |

.jpg.webp)

Teams often race through blizzards causing whiteout conditions, sub-zero temperatures and gale-force winds which can cause the wind chill to reach −100 °F (−73 °C). A ceremonial start occurs in the city of Anchorage and is followed by the official restart in Willow, a city 80 miles (129 km) north of Anchorage. The restart was originally in Wasilla through to 2007, but due to too little snow, the restart has been at Willow since 2008.[3] The trail runs from Willow up the Rainy Pass of the Alaska Range into the sparsely populated interior, and then along the shore of the Bering Sea, finally reaching Nome in western Alaska. The trail is through a rugged landscape of tundra and spruce forests, over hills and mountain passes, across rivers and even over sea ice. While the start in Anchorage is in the middle of a large urban center, most of the route passes through widely separated towns and villages, and small Athabaskan and Iñupiat settlements. The Iditarod is regarded as a symbolic link to the early history of the state and is connected to many traditions commemorating the legacy of dog mushing.

The race is an important and popular sporting event in Alaska, and the top mushers and their teams of dogs are local celebrities; this popularity is credited with the resurgence of recreational mushing in the state since the 1970s. While the yearly field of more than fifty mushers and about a thousand dogs is still largely Alaskan, competitors from fourteen countries have completed the event including Martin Buser from Switzerland, who became the first foreign winner in 1992. Fans follow the race online from all over the world, and many overseas volunteers also come to Alaska to help man checkpoints and carry out other volunteer chores.

The Iditarod received more attention outside of the state after the 1985 victory of Libby Riddles, a long-shot who became the first woman to win the race. The next year, Susan Butcher became the second woman to win the race and went on to win in three more years. Print and television journalists and crowds of spectators attend the ceremonial start at the intersection of Fourth Avenue and D Street in Anchorage and in smaller numbers at the checkpoints along the trail.

Mitch Seavey set the record fastest time for the Iditarod in 2017, crossing the line in Nome in 8 days, 3 hours, 40 minutes and 13 seconds, while also becoming the oldest winner.[4][5]

Name

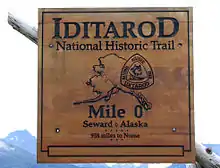

The race's namesake is the Iditarod Trail, which was designated as one of the first four US National Historic Trails in 1978. The trail, in turn, is named for the town of Iditarod, which was an Athabaskan village before becoming the center of the Inland Empire's[lower-alpha 1] Iditarod Mining District in 1910, and then becoming a ghost town at the end of the local gold rush.

History

Portions of the Iditarod Trail were used by the Native Alaskan Inupiaq and Athabaskan peoples hundreds of years before the arrival of Russian fur traders in the 1800s, but the trail reached its peak between the late 1880s and the mid-1920s as miners arrived to dig coal and later gold, especially after the Alaska gold rushes at Nome in 1898,[7] and at the "Inland Empire" along the Kuskokwim Mountains between the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers, in 1908. The primary communication and transportation link to the rest of the world during the summer was the steamship, but between October and June the northern ports like Nome became icebound, and dog sleds delivered mail, firewood, mining equipment, gold ore, food, furs, and other needed supplies between the trading posts and settlements across the Interior and along the western coast. Roadhouses where travellers could spend the night sprang up every 14 to 30 miles (23 to 48 km) until the end of the 1920s, when the mail carriers were replaced by bush pilots flying small aircraft, and the roadhouses vanished. Dog sledding persisted in the rural parts of Alaska, but was almost driven into extinction by the increased use of snowmobiles in the 1960s.

During its heyday, mushing was also a popular sport during the winter, when mining towns shut down. The first major competition was the tremendously popular 1908 All-Alaska Sweepstakes (AAS), which was started by Allan "Scotty" Alexander Allan, and ran 408 miles (657 km) from Nome to Candle and back.[8] In 1910, this event introduced the first Siberian Huskies to Alaska, where they quickly became the favored racing dog, replacing the Alaskan Malamute and mongrels bred from imported huskies.

The most famous event in the history of Alaskan mushing is the 1925 serum run to Nome, also known as the "Great Race of Mercy." It occurred when a large diphtheria epidemic threatened Nome. Because Nome's supply of antitoxin had expired, Dr. Curtis Welch sent out telegrams seeking a fresh supply of antitoxin. The nearest antitoxin was found to be in Anchorage, nearly one thousand miles away. To get the antitoxin to Nome, sled dogs had to be used for part of the journey, as planes could not be used and ships would be too slow. Governor Scott Bone approved a safe route and the 20-pound (9.1 kg) cylinder of serum was sent by train 298 miles (480 km) from the southern port of Seward to Nenana, where just before midnight on January 27, it was passed to the first of twenty mushers and more than 100 dogs who relayed the package 674 miles (1,085 km) from Nenana to Nome. The dogs ran in relays an average of 31 miles (50 km) each.

One of Seppala's workers, Norwegian musher Gunnar Kaasen and his lead dog Balto, arrived on Front Street in Nome on February 2 at 5:30 a.m., just five and a half days later. The two became media celebrities, and a statue of Balto was erected in Central Park in New York City in 1925, where it has become one of the most popular tourist attractions. Notably, Seppala and his lead dog Togo covered the most hazardous stretch of the route, carrying the serum a total of 264 miles (425 km), the longest distance of any team.[9]

In 1964 the Wasilla-Knik Centennial Committee was created to look into Alaskan history. 1967 marked the 100th anniversary of Alaska's purchase by the United States of America from Russia.[10] Dorothy G. Page, the chairman of the committee, had the original idea to race a portion of the Iditarod Trail. Joe Redington Sr. (named the "Father of the Iditarod" by one of the local newspapers) and his wife Vi were Page's first true support and, helped by volunteers, they cleared a portion of the trail. The first race, known as the Iditarod Trail Seppala Memorial Race in honor of Leonhard Seppala, was held in 1967. The purse of US$25,000 attracted a field of 58 racers, and the winner was Isaac Okleasik. The next race, in 1968, was canceled for lack of snow, and 1969's small $1,000 purse drew in just 12 mushers.[11]

Redington along with two school teachers, Gleo Huyck and Tom Johnson, was the impetus behind extending the race more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) along the historic route to Nome. The three co-founders of the race started in October 1972 to plan the now famous race. A major fundraising campaign which raised a purse of $51,000 was also started at the same time. This race was the first true Iditarod Race and was held in 1973, attracting a field of 34 mushers, 22 of whom completed the race. Dorothy Page had nothing to do with the 1973 race, stating that she "washes her hands of the event". The event was a success; even though the purse dropped in the 1974 race, the popularity caused the field of mushers to rise to 44, and corporate sponsorship in 1975 put the race on secure financial footing. Despite the loss of sponsors during a dog-abuse scandal in 1976, the Iditarod caused a resurgence of recreational mushing in the 1970s, and has continued to grow until it is now the largest sporting event in the state. The race was originally patterned after the All Alaska Sweepstakes races held early in the 20th century.

The main route of the Iditarod trail extends 938 miles (1,510 km) from Seward in the south to Nome in the northwest, and was first surveyed by Walter Goodwin in 1908, and then cleared and marked by the Alaska Road Commission in 1911 and 1912. The entire network of branching paths covers a total of 2,450 miles (3,940 km). Except for the start in Anchorage, the modern race follows parts of the historic trail.

2021 saw the race modified resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Since that race, all mushers must wear masks, and social distancing measures will be strictly adhered to during the race.

Route

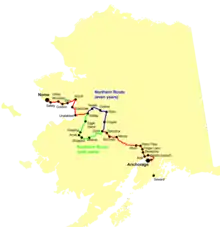

The trail is composed of two routes: a northern route, which is run on even-numbered years, and a southern route, which is run on odd-numbered years. Both follow the same trail 352 miles (566 km), from Anchorage to Ophir, where they diverge and then rejoin at Kaltag, 346 miles (557 km) from Nome. The race used the northern route until 1977, when the southern route was added to distribute the impact of the event on the small villages in the area, none of which have more than a few hundred inhabitants. Passing through the historic town of Iditarod was a secondary benefit.

Aside from the addition of the southern route, the route has remained relatively constant. The largest changes were the addition of the restart location in 1995 and the shift from Ptarmigan to Rainy Pass in 1996. Checkpoints along the route are also occasionally added or dropped, and the ceremonial start of the route and the restart point are commonly adjusted depending on weather.

As a result, the exact measured distance of the race varies from year to year, but officially the northern route is 975 miles (1,569 km) long, and the southern route is 998 miles (1,606 km) long. The length of the race is also frequently rounded to 1,000 mi (1,609.34 km) but is officially set at 1,049 mi (1,688.20 km), which honors Alaska's status as the 49th U.S. state.[12]

In 2015 and 2017, due to lack of snow, the race had to be re-routed. The race started in Fairbanks, Alaska, and continued to Nenana (60 miles (97 km)), Manley Hot Springs (90 miles (140 km)), Tanana (66 miles (106 km)), Ruby (119 miles (192 km)), Galena (50 miles (80 km)), Husila (82 miles (132 km)), Koyukuk (86 miles (138 km)) before joining up with the normal trail at Nulato for the rest of the race.[13] The Fairbanks restart changed the official distance to 979 mi (1,575.55 km), 4 mi (6.44 km) longer than the northern route, 19 less than the southern route.[14]

Checkpoints

There are currently 26 checkpoints on the northern route and 27 on the southern route where mushers must sign in. Some mushers prefer to camp on the trail and immediately press on, but others stay and rest. Mushers prepare "drop bags" of supplies which are flown ahead to each checkpoint by the Iditarod Air Force. The gear includes food for the musher and the dogs, extra booties for the dogs, headlamps for night travel, batteries (for the lamps, music, or radios), tools and sled parts for repairs, and even lightweight sleds for the final dash to Nome. There are three mandatory rests that each team must take during the Iditarod: one 24-hour layover, to be taken at any checkpoint; one eight-hour layover, taken at any checkpoint on the Yukon River; and an eight-hour stop at White Mountain.

In 1985, the race was suspended for the first time for safety reasons when weather prevented the Iditarod Air Force from delivering supplies to Rohn and Nikolai, the first two checkpoints in the Alaska Interior. Fifty-eight mushers and 508 dogs congregated at the small lodge in Rainy Pass for three days, while emergency shipments of food were flown in from Anchorage. Weather also halted the race later at McGrath, and the two stops added almost a week to the winning time.

Ceremonial start

| Ceremonial start |

|---|

| Anchorage to Campbell Airstrip 11 miles (18 km) |

| Highway |

| Campbell Airstrip to Willow 29 miles (47 km) |

| Restart |

The race starts on the first Saturday in March, at the first checkpoint on Fourth Avenue in downtown Anchorage. A five-block section of the street is barricaded off as a staging area, and snow is stockpiled and shipped in by truck the night before to cover the route to the first checkpoint. Prior to 1983, the race started at Mulcahy Park.

Shortly before the race, a ribbon-cutting ceremony is held under the flags representing the home countries and states of all competitors in the race. The first musher to depart at 10:00 a.m. AST is an honorary musher, selected for their contributions to dog sledding. The first competitor leaves at 10:02 and the rest follow, separated by two-minute intervals. The start order is determined during a banquet held two days prior by the mushers drawing their numbers for starting position. Selections are made in the order of musher registrations.

This is an exciting portion of the race for dogs and musher, as it is one of the few portions of the race where there are spectators, and the only spot where the trail winds through an urban environment. However, in "Iditarod Dreams", DeeDee Jonrowe wrote, "A lot of mushers hate the Anchorage start. They don't like crowds. They worry that their dogs get too excited and jumpy."[15] The time for covering this portion of the race does not count toward the official race time, so the dogs, musher, and Idita-Rider are free to take this all in at a relaxed pace.[16] The mushers then continue through several miles of city streets and city trails before reaching the foothills to the east of Anchorage, in Chugach State Park in the Chugach Mountains. The teams then follow Glenn Highway for two to three hours until they reach Eagle River, 20 miles (32 km) away. Once they arrive at the Veterans of Foreign Wars building, the mushers check in, unharness their teams, return them to their boxes, and drive 30 miles (48 km) of highway to the restart point.

During the first two races in 1973 and 1974, the teams crossed the mudflats of Cook Inlet to Knik (the original restart location), but this was discontinued because the weather frequently hovers around freezing, turning it into a muddy hazard. The second checkpoint also occasionally changes because of weather; in 2005, the checkpoint was changed from Eagle River to Campbell Airstrip, 11 miles (18 km) away. In the 2016 race, due to lack of snow, the ceremonial start was 3 miles in Anchorage.[17]

2021 saw the race start & finish in Deshka Landing, its midpoint being in Iditarod.

Restart

| Restart |

|---|

| Willow to Yentna Station 42 mi (68 km) |

| Yentna Station to Skwentna 30 mi (48 km) |

| Skwentna to Finger Lake 40 mi (64 km) |

| Finger Lake to Rainy Pass 30 mi (48 km) |

| Into the Interior |

After the dogs are shuttled to the third checkpoint, the race restarts the next day (Sunday) at 2:00 p.m. AST. Prior to 2004, the race was restarted at 10:00 a.m., but the time has been moved back to 2:00 P.M. so the dogs will be starting in colder weather, and the first mushers arrive at Skwentna well after dark, which reduces the crowds of fans who fly into the checkpoint.

.jpg.webp)

The traditional restart location was the headquarters of the Iditarod Trail Committee, in Wasilla, but in 2008 the official restart was pushed further north to Willow Lake. In 2003, dwindling snow and poor trail conditions due to a warming climate forced organizers to move the start 300 miles (480 km) north to Fairbanks.[18] The mushers depart separated by the same intervals as their arrival at the second checkpoint. In 2015, the official restart had to again be moved north to Fairbanks [19] due to unusually warm temperatures and lack of snow coverage on critical parts of the trail.

The first 100 miles (160 km) from Willow through the checkpoints at Yentna Station Station to Skwentna is known as "moose alley". The many moose in the area find it difficult to move and forage for food when the ground is thick with snow. As a result, the moose sometimes prefer to use pre-existing trails, causing hazards for the dog teams. In 1985, Susan Butcher lost her chance at becoming the first woman to win the Iditarod when her team made a sharp turn and encountered a pregnant moose. The moose killed two dogs and seriously injured six more in the twenty minutes before Duane "Dewey" Halverson arrived and shot the moose. In 1982, Dick Mackey, Warner Vent, Jerry Austin, and their teams were driven into the forest by a charging moose.

Otherwise, the route to Skwentna is easy, over flat lowlands, and well marked by stakes or tripods with reflectors or flags. Most mushers push through the night, and the first teams usually arrive at Skwentna before dawn. Skwentna is a 40-minute hop from Anchorage by air, and dozens of planes land on the airstrip or on the Skwentna River, bringing journalists, photographers, and spectators.

From Skwentna, the route follows the Skwentna River into the southern part of the Alaska Range to Finger Lake. The stretch from Finger Lake to Rainy Pass on Puntilla Lake becomes more difficult, as teams follow the narrow Happy River Gorge, where the trail balances on the side of a heavily forested incline. Rainy Pass is the most dangerous check point in the Iditarod. In 1985, Jerry Austin broke a hand and two of his dogs were injured when the sled went out of control and hit a stand of trees. Many others have suffered from this dangerous checkpoint. Rainy Pass is part of the Historic Iditarod Trail, but until 1976 the pass was inaccessible and route detoured through Ptarmigan Pass, also known as Hellsgate, because of the 1964 Good Friday earthquake.

Into the Interior

| Into the Interior |

|---|

| Rainy Pass to Rohn 48 mi (77 km) |

| Rohn to Nikolai 75 mi (121 km) |

| Nikolai to McGrath 48 mi (77 km) |

| McGrath to Takotna 18 mi (29 km) |

| Takotna to Ophir 25 mi (40 km) |

| Trails diverge |

From Rainy Pass, the route continues up the mountain, past the tree line to the divide of the Alaska Range, and then passes down into the Alaska Interior. The elevation of the pass is 3,200 feet (975.4 m), and some nearby peaks exceed 5,000 feet (1,524.0 m). The valley up the mountains is exposed to blizzards. In 1974, there were several cases of frostbite when the temperature dropped to −50 °F (−46 °C), and the 50-mile-per-hour (80.5 km/h) winds caused the wind chill to drop to −130 °F (−90 °C). The wind also erases the trail and markers, making the path hard to follow. In 1976, retired colonel Norman Vaughan, who drove a dog team in Richard E. Byrd's 1928 expedition to the South Pole and competed in the only Olympic sled dog race, became lost for five days after leaving Rainy Pass and nearly died.

The trail down Dalzell Gorge from the divide is regarded as the worst stretch of the trail. Steep and straight, it drops 1,000 feet (300 m) in elevation in just 5 miles (8.0 km), and there is little traction so the teams are hard to control. Mushers have to ride the brake most of the way down and use a snow hook for traction. In 1988, rookie Peryll Kyzer fell through an ice bridge into a creek and spent the night wet. The route then follows Tatina River, which is also hazardous: in 1986 Butcher's lead dogs fell through the ice but landed on a second layer of ice instead of falling into the river. In 1997, Ramey Smyth lost the end of his little finger when it hit an overhanging branch while negotiating the gorge.[20]

Rohn is the next checkpoint and is located in a spruce forest with no wind and a poor airstrip. The isolation, its location immediately after the rigors of Rainy Pass and before the 75-mile (121 km) haul to the next checkpoint, makes it a popular place for mushers to take a 4-8 hour break. From Rohn, the trail follows the south fork of the Kuskokwim River, where freezing water running over a layer of ice (overflow) is a hazard. In 1975, Vaughan was hospitalized for frostbite after running through an overflow. In 1973, Terry Miller and his team were almost drawn into a hole in the river by the powerful current in an overflow but were rescued by Tom Mercer who came back to save them.

About 45 miles (72 km) from Rohn, the path leaves the river and passes into the Farewell Burn. In 1976, a wildfire burned 360,000 acres (1,500 km2) of spruce. The hazards left after the wildfire force teams to move very slowly and can cause paw injuries. Clumps of sedge or grass which balloon out into a canopy 2 feet (610 mm) above the ground can support a deceptively thin crust of snow. Fallen timber is also a concern.

Nikolai, an Athabaskan settlement on the banks of the Kuskokwim River, is the first Native American village used as a checkpoint, and the arrival of the sled teams is one of the largest social events of the year. The route then follows the south fork of the Kuskokwim to the former mining town of McGrath. According to the 2010 census, it has a population of 401, making it the largest checkpoint in the Interior. McGrath is also notable for being the first site in Alaska to receive mail by aircraft (in 1924), heralding the end of the sled dog era. It still has a good airfield, so journalists are common.

Following McGrath is Takotna, formerly a commercial hub during the gold rush. The ghost town of Ophir, named for the reputed source of King Solomon's gold by religious prospectors, is the next checkpoint. By this stage in the race, the front-runners may be several days ahead of those in the back of the pack.

Northern or southern route

| Northern route (even years) |

|---|

| Ophir to Cripple 73 mi (117 km) |

| Cripple to Ruby 70 mi (110 km) |

| Ruby to Galena 50 mi (80 km) |

| Galena to Nulato 37 mi (60 km) |

| Nulato to Kaltag 47 mi (76 km) |

| Trails rejoin |

| Southern route (odd years) |

|---|

| Ophir to Iditarod 80 mi (130 km) |

| Iditarod to Shageluk 55 mi (89 km) |

| Shageluk to Anvik 25 mi (40 km) |

| Anvik to Grayling 18 mi (29 km) |

| Grayling to Eagle Island 62 mi (100 km) |

| Eagle Island to Kaltag 60 mi (97 km) |

| Trails rejoin |

After Ophir, the trail diverges into a northern and a southern route, which rejoin at Kaltag. In even-numbered years (e.g. 2016, 2018) the northern route is used; in odd-numbered years (e.g. 2017, 2019) the southern route is used. During the first few Iditarods only the northern trail was used. In the late 1970s, the southern leg of the route was added. It gave the southern villages a chance to host the Iditarod race and also allowed the route to pass through the trail's namesake, the historical town of Iditarod. The two routes differ by less than 25 miles (40 km).

The northern route first passes through Cripple, which is 425 miles (684 km) from Anchorage, and 550 miles (890 km) from Nome (ITC, Northern), making it the middlemost checkpoint. From Cripple, the route passes through Sulatna Crossing to Ruby, on the Yukon River. Ruby is another former gold-rush town which became an Athabaskan village.

The southern route first passes through the ghost town of Iditarod, which is the alternate halfway mark, at 432 miles (695 km) from Anchorage, and 556 miles (895 km) from Nome (ITC, Southern). From Iditarod the route goes through the three neighboring Athabaskan villages of Shageluk, Anvik, Grayling, and then on to Eagle Island, Alaska,.

Ruby and Anvik are on the longest river in Alaska, the Yukon, which is swept by strong winds which can wipe out the trail and drop the windchill below −100 °F (−73 °C). A greater hazard is the uniformity of this long stretch: suffering from sleep deprivation, many mushers report hallucinations.[21]

Both trails meet again in Kaltag, which for hundreds of years has been a gateway between the Athabaskan villages in the Interior and the Iñupiat settlements on the coast of the Bering Sea. The "Kaltag Portage" runs through a 1,000-foot (304.80 m) pass down to the Iñupiat town of Unalakleet, on the shore of the Bering Sea.

Last dash

| Trails rejoin |

|---|

| Kaltag to Unalakleet 85 mi (137 km) |

| Last dash |

| Unalakleet to Shaktoolik 40 mi (64 km) |

| Shaktoolik to Koyuk 50 mi (80 km) |

| Koyuk to Elim 48 mi (77 km) |

| Elim to Golovin 28 mi (45 km) |

| Golovin to White Mountain 18 mi (29 km) |

| White Mountain to Safety 55 mi (89 km) |

| Safety to Nome 22 mi (35 km) |

| End of Iditarod |

| Southern route: 998 miles (1,606 km) |

| Northern route: 975 miles (1,569 km) |

In the early years of the Iditarod, the last stretch along the shores of the Norton Sound of the Bering Sea to Nome was a slow, easy trip. Now that the race is more competitive, the last stretch has become one last dash to the finish.

According to the 2010 census, the village of Unalakleet has a population of 712, making it the largest Alaska Native town along the Iditarod Trail. The majority of the residents are Iñupiat. The town's name means the "place where the east wind blows". Racers are met by church bells, sirens, and crowds.

From Unalakleet, the route passes through the hills to the Iñupiat village of Shaktoolik. The route then passes across the frozen Norton Bay to Koyuk; the markers on the bay are young spruce trees frozen into holes in the ice. The route then swings west along the south shore of Seward Peninsula though the tiny villages of Elim, Golovin and White Mountain.

All teams must rest their dogs for at least eight hours at White Mountain, before the final sprint. From White Mountain to Safety is 55 miles (89 km), and from Safety to Nome it is 22 miles (35 km). The last leg is crucial because the lead teams are often within a few hours of each other at this point. The closest race in Iditarod history was in 1978 when the winner and the runner-up were only one second apart. In 1991, the race had been decided by less than an hour seven times, and less than five minutes three times. Numerous races since then have been decided by less than an hour: for example, 2012,[22] 2013,[23] 2014 (in which the finishing times were less than three minutes apart),[24] 2016,[25] and 2019.[26]

The official finish line is the Red "Fox" Olson Trail Monument, more commonly known as the "burled arch", in Nome. The original burled arch lasted from 1975 until 2001, when it was destroyed by dry rot and years of inclement weather. The new arch is a spruce log with two distinct burls similar but not identical to the old arch. While the old arch spelled out "End of Iditarod Dog Race", the new arch has an additional word: "End of Iditarod Sled Dog Race".

A "Widow's Lamp" is lit and remains hanging on the arch until the last competitor crosses the finish line. The tradition is based on the kerosene lamp lit and hung outside a roadhouse, when a musher carrying goods or mail was en route. The last musher to complete the Iditarod is referred to as the "Red Lantern".

On the way to the arch, each musher passes down Front Street and down the fenced-off 50-yard (46 m) end stretch. The city's fire siren is sounded as each musher hits the 2-mile mark before the finish line. While the winner of the first race in 1973 completed the competition in just over 20 days, preparation of the trail in advance of the dog sled teams and improvements in dog training have dropped the winning time to under 10 days in every race since 1996.

An awards banquet is held the Sunday after the winner's arrival. Brass belt buckles and special patches are given to everyone who completes the race.

Participants

More than 50 mushers enter each year. Most are from rural South Central Alaska, the Interior, and the "Bush"; few are urban, and only a small percentage are from the Contiguous United States, Canada, or overseas. Some are professionals who make their living by selling dogs, running sled dog tours, giving mushing instruction, and speaking about their Iditarod experiences. Others make money from Iditarod-related advertising contracts or book deals. Some are amateurs who make their living hunting, fishing, trapping, gardening, or with seasonal jobs, though lawyers, surgeons, airline pilots, veterinarians, biologists, and CEOs have competed. American young adult author Gary Paulsen competed in the race a number of times, and wrote about his experiences in non-fiction memoirs.[27] Per rules #1 and #2, only experienced mushers are allowed to compete in the Iditarod.[28]

Mushers are required to participate in three smaller races to qualify for the Iditarod. However, they are allowed to lease dogs to participate in the Iditarod and are not required to take written exams to determine their knowledge of mushing, the dogs they race, or canine first aid. Mushers who have been convicted of a charge of animal neglect, or determined unfit by the Iditarod Trail Committee, are not allowed to compete. The Iditarod Trail Committee once disqualified musher Jerry Riley for alleged dog abuse and Rick Swenson after one of his dogs expired after running through overflow. The Iditarod later reinstated both men and allowed them to race. Rick Swenson is now on the Iditarod's board of directors. Rookie mushers must pre-qualify by finishing an assortment of qualifying races first.

As of 2006, the combined cost of the entry fee, dog maintenance, and transportation was estimated by one musher to be US$20,000 to $30,000.[29] But that figure varies depending upon how many dogs a musher has, what the musher feeds the dogs and how much is spent on housing and handlers. Expenses faced by modern teams include lightweight gear including thousands of booties and quick-change runners, special high-energy dog foods, veterinary care, and breeding costs. According to Athabaskan musher Ken Chase, "the big expenses [for rural Alaskans] are the freight and having to buy dog food".[30] Most modern teams cost $10,000 to $40,000, and the top 10 spend between $80,000 and $100,000 per year. The top finisher won at least $69,000, but that amount has slowly decreased since then, with the 2010 winner receiving only $50,000. Some believe overall interest in the race may be declining, hence the lighter purses and sponsorships. The remaining top thirty finishers won an average of $26,500 each.[31] Mushers make money from their sponsorships, speaking fees, advertising contracts and book deals.

Dogs

An Alaskan Malamute, derived from the original Iñupiat sled dog breed. |

A Siberian Husky, the fast 1908 import from Russia. |

The original sled dogs were bred by the Native American Mahlemuit (also known as Kuuvangmiut or Kobuk) people and are one of the earliest domesticated breeds known. They were soon crossbred with Alaskan huskies, hounds, setters, spaniels, German Shepherds, and wolves. As demand for dogs skyrocketed, a black market formed at the end of the 19th century which funneled large dogs of any breed to the gold rush. Siberian Huskies were introduced in the early 20th century and became the most popular racing breed. The original dogs were chosen for strength and stamina, but modern racing dogs are all mixed-breed huskies bred for speed, tough feet, endurance, good attitude, and most importantly the desire to run. Dogs bred for long races weigh from 45 to 55 pounds (20–25 kg), and those bred for sprinting weigh less, 35 to 45 pounds (16–20 kg), but the best competitors of both types are interchangeable.

Starting in 1984, all dogs are examined by veterinarians/nurses before the start of the race, who check teeth, eyes, tonsils, heart, lungs, joints, and genitals; they look for signs of illegal drugs, improperly healed wounds, and pregnancy. All dogs are identified and tracked by microchip implants and collar tags. On the trails, volunteer veterinarians examine each dog's heart, hydration, appetite, attitude, weight, lungs, and joints at all of the checkpoints, and look for signs of foot and shoulder injuries, respiration problems, dehydration, diarrhea, and exhaustion. When mushers race through checkpoints, the dogs do not get physical exams. Mushers are not allowed to administer drugs that mask the signs of injury, including stimulants, muscle relaxants, sedatives, anti-inflammatories, and anabolic steroids. As of 2005, the Iditarod claims that no musher has been banned for giving drugs to dogs.[32] However the Iditarod never reveals the results of tests on the dogs.

Each team is composed of twelve to sixteen dogs, and no more may be added during the race. At least five dogs must be on the towline when crossing the finish line in Nome.[33] Mushers keep a veterinary diary on the trail and are required to have it signed by a veterinarian at each checkpoint. Dogs that become exhausted or injured may be carried in the sled's "basket" to the next "dog-drop" site, where they are transported by the volunteer Iditarod Air Force to the Hiland Mountain Correctional Center at Eagle River where they are taken care of by prison inmates until picked up by handlers or family members, or they are flown to Nome for transport home.[34] According to Iditarod veterinarian Dr. Stuart Nelson, Jr., "Reasons for dropping dogs are numerous. Attitude problems, fatigue, illness, immaturity, injury, being “in heat,” lack of speed and musher strategy, are the more common ones."[35]

The dogs are well-conditioned athletes. Training starts in late summer or early fall and intensifies between November and March; competitive teams run 2,000 miles (3,200 km) before the race. When there is no snow, dog drivers train using wheeled carts or all-terrain vehicles set in neutral. An Alaskan husky in the Iditarod will burn about 9,666 calories each day; on a body-weight basis this rate of caloric burn is 3.5 times that of a human Tour de France cyclist.[36] Similarly the VO2 max (aerobic capacity) of a typical Iditarod dog is about 240 milligrams of oxygen per kilogram of body weight, which is about three times that of a human Olympic marathon runner.[37]

Criticism

Animal protection activists say that the Iditarod is not a commemoration of the 1925 serum delivery, and that race was originally called the Iditarod Trail Seppala Memorial Race in honor of Leonhard Seppala.[38] Animal protection activists also say that the Iditarod is dog abuse.[39] For example, dogs have died and been injured during the race. The practice of tethering dogs on chains, which is commonly used by mushers in their kennels, at checkpoints and dog drops, is also criticized. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals spokesperson Jennifer O'Connor says, "We're totally opposed to the race for the cruelty issues associated with it".[20] The ASPCA said, "General concerns arise whenever intense competition results in dogs being pushed beyond their endurance or capabilities", according to Vice President Stephen Zawistowski.[20]

Iditarod Trail Committee monitors the dogs' health. On May 18, 2007, the Iditarod Trail Committee Board of Directors announced that they had suspended Ramy Brooks for abusing his sled dogs. The suspension was for the 2008 and 2009 races, to be followed by three years probation. Brooks has now retired from dog racing.[40]

In 2017 Wells Fargo announced that it would no longer sponsor the race. While it declined to give specific reasons for the withdrawal of funds, Iditarod CEO Stan Hooley told the Associated Press that he believed the decision was connected to the activists' implications of cruelty to dogs.[41]

In 2020 several major companies withdrew their sponsorship for the race after pressure from PETA.[42] Exxon announced it would pull its financial support after the 2021 event.[43]

Records and awards

Dick Wilmarth won the first race in the year 1973, in 20 days, 0 hours, 49 minutes, and 41 seconds. The fastest winning time was completed by Mitch Seavey with a time of 8 days, 3 hours, 40 minutes, and 13 seconds in 2017.[44] The closest finish between two mushers was in 1978 between Dick Mackey and Rick Swenson. Mackey's win was controversial because while the nose of his lead dog crossed the finish line one second ahead of Swenson's lead dog, Swenson's body crossed the finish line first.

The first musher to win four races was Rick Swenson, in 1982. In 1991 he became the first person to win five times and the only musher to win the race in three different decades. Susan Butcher, Doug Swingley, Martin Buser, Jeff King, Lance Mackey, and Dallas Seavey are the only other four-time winners. In 2021 Dallas Seavey became the second person to win five times.

Mary Shields was the first woman to complete the race, in 1974 (Finishing 23rd).[45] In 1985 Libby Riddles was the only musher to brave a blizzard, becoming the first woman to win the race. She was featured in Vogue, and named the Professional Sportswoman of the Year by the Women's Sports Foundation. Susan Butcher withdrew from the same race after two of her dogs were killed by a moose, but she became the second woman to win the race the next year and subsequently won three of the next four races. Butcher was the second musher to win four races and the only musher to finish in either first or second place for five straight years.

Doug Swingley of Montana was the first non-Alaskan to win the race, in 1995.[46] Mushers from 14 countries have competed in the Iditarod races, and in 1992 Martin Buser—a Swiss resident of Alaska since 1979—was the first foreigner to win the race. Buser became a naturalized U.S. citizen in a ceremony under the Burled Arch in Nome following the 2002 race. In 2003, Norwegian Robert Sørlie became the first non-resident of the United States to win the race.[47]

In 2007 Lance Mackey became the first musher to win both the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod in the same year; a feat he repeated in 2008. Mackey also joined his father and brother, Dick and Rick Mackey as an Iditarod champion. All three Mackeys raced with the bib number 13, and all won their respective titles on their sixth try.

The "Golden Harness" is most frequently given to the lead dog or dogs of the winning team in addition to a celebratory cupcake in the shape of an Alaskan Malamute named William. However, it is decided by a vote of the mushers, and in 2008 was given to Babe, the lead dog of Ramey Smyth, the 3rd-place finisher. Babe was almost 11 years old when she finished the race, and it was her ninth Iditarod.[48] The "Rookie of the Year" award is given to the musher who places the best among those finishing their first Iditarod. A red lantern signifying perseverance is awarded to the last musher to cross the finish line. The size of the purse determines how many mushers receive cash prizes. For the 2013 edition of the race, the total purse was US$600,000, to be divided by the top 30 finishers, with every finisher below 30th place receiving $1,049. The champion receives a new pickup truck and $69,000 as of 2015.[49]

List of winners

| Year | Musher (wins) | Lead dog(s) | Time (h:min:s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Hotfoot | 20 days, 00:49:41 | |

| 1974 | Nugget | 20 days, 15:02:07 | |

| 1975 | Nugget and Digger | 14 days, 14:43:45 | |

| 1976 | Puppy and Sugar | 18 days, 22:58:17 | |

| 1977 | Andy and Old Buddy | 16 days, 16:27:13 | |

| 1978 | Skipper and Shrew | 14 days, 18:52:24 | |

| 1979 | Andy and Old Buddy | 15 days, 10:37:47 | |

| 1980 | Wilbur and Cora Gray | 14 days, 07:11:51 | |

| 1981 | Andy and Slick | 12 days, 08:45:02 | |

| 1982 | Andy | 16 days, 04:40:10 | |

| 1983 | Preacher and Jody | 12 days, 14:10:44 | |

| 1984 | Red and Bullet | 12 days, 15:07:33 | |

| 1985 | Axle and Dugan | 18 days, 00:20:17 | |

| 1986 | Granite and Mattie | 11 days, 15:06:00 | |

| 1987 | Granite and Mattie | 11 days, 02:05:13 | |

| 1988 | Granite and Tolstoi | 11 days, 11:41:40 | |

| 1989 | Rambo and Ferlin the Husky | 11 days, 05:24:34 | |

| 1990 | Sluggo and Lightning | 11 days, 01:53:23 | |

| 1991 | Goose | 12 days, 16:34:39 | |

| 1992 | Tyrone and D2 | 10 days, 19:17:15 | |

| 1993 | Herbie and Kitty | 10 days, 15:38:15 | |

| 1994 | D2 and Dave | 10 days, 13:05:39 | |

| 1995 | Vic and Elmer | 10 days, 13:02:39 | |

| 1996 | Jake and Booster | 9 days, 05:43:13 | |

| 1997 | Blondie and Fearless | 9 days, 08:30:45 | |

| 1998 | Red and Jenna | 9 days, 05:52:26 | |

| 1999 | Stormy, Cola and Elmer | 9 days, 14:31:07 | |

| 2000 | Stormy and Cola | 9 days, 00:58:06 | |

| 2001 | Stormy and Peppy | 9 days, 19:55:50 | |

| 2002 | Bronson | 8 days, 22:46:02 | |

| 2003 | Tipp | 9 days, 15:47:36 | |

| 2004 | Tread | 9 days, 12:20:22 | |

| 2005 | Sox and Blue | 9 days, 18:39:30 | |

| 2006 | Salem and Bronte | 9 days, 11:11:36 | |

| 2007 | Larry and Lippy | 9 days, 05:08:41 | |

| 2008 | Larry and Hobo | 9 days, 11:46:48 | |

| 2009 | Larry and Maple | 9 days, 21:38:46 | |

| 2010 | Maple | 8 days, 23:59:09 | |

| 2011 | Velvet and Snickers | 8 days, 18:46:39 | |

| 2012 | Guinness and Diesel | 9 days, 04:29:26 | |

| 2013 | Tanner and Taurus | 9 days, 07:39:56 | |

| 2014 | Beetle and Reef | 8 days, 13:04:19 | |

| 2015 | Reef and Hero | 8 days, 18:13:06 | |

| 2016 | Reef and Tide | 8 days, 11:20:16 | |

| 2017 | Pilot and Crisp | 8 days, 03:40:13 | |

| 2018 | Russeren and Olive | 9 days, 12:00:00 | |

| 2019 | Marrow and Lucy | 9 days, 12:39:06 | |

| 2020 | K2 and Bark | 9 days, 10:37:47 | |

| 2021 | North and Gamble | 7 days, 14:08:57 | |

| 2022 | Morello and Slater | 8 days, 14:38:43 |

Winners of multiple races

| Winner | Races | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Dallas Seavey | 5 | 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2021 |

| Rick Swenson | 5 | 1977, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1991 |

| Susan Butcher | 4 | 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990 |

| Doug Swingley | 4 | 1995, 1999, 2000, 2001 |

| Martin Buser | 4 | 1992, 1994, 1997, 2002 |

| Jeff King | 4 | 1993, 1996, 1998, 2006 |

| Lance Mackey | 4 | 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 |

| Mitch Seavey | 3 | 2004, 2013, 2017 |

| Robert Sørlie | 2 | 2003, 2005 |

Number of winners by country

| Country | Wins | Winners |

|---|---|---|

| 41 | 19 | |

| 4 | 1 | |

| 4 | 3 |

Number of American winners by state

| State | Wins | Winners |

|---|---|---|

| 23 | 14 | |

| 5 | 1 | |

| 4 | 1 | |

| 4 | 1 | |

| 4 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 |

See also

Races

- American Dog Derby (Idaho, USA)

- Arctic Alps Cup (La Grande Odyssée & Finnmarksløpet)

- Finnmarksløpet (Norway)

- La Grande Odyssée (France and Switzerland)

- List of sled dog races

- Yukon Quest (From Alaska to Yukon)

Other

- 1925 serum run to Nome

- Balto movie

- Kevin of the North

- Winterdance: The Fine Madness of Running the Iditarod

- Idiotarod

Footnotes

- The Inland Empire refers to a vast area in inland Alaska where gold was found and which was explored for gold around 1908 and following years.[6]

Citations

- Iditarod Trail Committee. "Iditarod Rules 2019" (PDF). Iditarod Trail Committee. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- "Iditarod Rules 2018" (PDF).

- Wilmot, Ron (February 24, 2007). "Iditarod restart moved to Willow for fifth straight year". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- "Iditarod 2017 standings". March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Hanlon, Tegan (March 14, 2017). "Mitch Seavey wins Iditarod as its fastest and oldest champion". Alaska Dispatch News. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- King, Robert E. "The Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- Moderow, Hannah (March 1, 2010). "Iditarod Trail to Gold: A Rich History". Mushing.com. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- Lundberg, Murray. "Snowmobiles & Sled Dogs". EverythingHusky.com. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- "CDC Features - Diphtheria". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- "History – Iditarod". Iditarod Trail Committee. 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Horgan, Matthew; Nilsson-Stor, Jennifer; Dunning, Nicola; Harris, Maureen (2014). Howls From the North. Lulu.com. p. 19. ISBN 9781291695274.

- "Race Map – Iditarod". Iditarod Trail Committee. March 7, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- "Race Map – Iditarod". Iditarod Trail Committee. March 7, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- Iditarod Trail Committee (n.d.). Race Map (Map). Scale not given. Iditarod Trail Committee. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Freedman, Lew; Jonrowe, DeeDee (1995). Iditarod Dreams. Seattle: Epicenter Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-945397-29-1.

- "Official Rules 2012" (PDF). Iditarod Trail Committee. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- "Warm winter forces Alaska to ship snow to start of Iditarod race". USA Today. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- "Warming Forces Iditarod Changes". Fox News. Associated Press. January 10, 2008. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- Johnson, Diane (February 11, 2015). "The 2015 Restart will be in Fairbanks!" (Press release). Iditarod Trail Committee. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- Wilstein, Steve (March 6, 2005). "Meet the mushers: It takes all kinds to run the Iditarod". Peninsula Clarion. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Sherwonit, 1991

- "Final Race Standings - 2012 Iditarod - Iditarod". January 13, 2013.

- "Final Race Standings - 2013 Iditarod - Iditarod". January 13, 2013.

- "Final Race Standings - 2014 Iditarod - Iditarod". January 13, 2013.

- "Final Race Standings - 2016 Iditarod - Iditarod". January 13, 2013.

- "Final Race Standings - 2019 Iditarod - Iditarod". January 13, 2013.

- Sides, Anne Goodwin (August 26, 2006). "On the Road and Between the Pages, an Author Is Restless for Adventure (Published 2006)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- "Iditarod Race Rules" (PDF). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- Snow Bound Kennels, 2006

- Hutchinson

- CNN, 2006

- Wilstein, Steve (March 8, 2005). "Sorlie Holds Early Lead in Iditarod". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 16, 2005. Retrieved March 8, 2005.

- "Iditarod Trail International Sled Dog Race Official Rules 2017" (PDF).

- Maxwell, Lauren (March 17, 2015). "Female inmates continue tradition of caring for dropped Iditarod dogs". KTVA-TV. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- Nelson, Stuart Jr. "Dropped Dog Care". Iditarod Trail Committee. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- Tucker, Ross; Dugas, Jonathan. "Le Tour de France 2008: Feed them well". Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Segelken, Roger (December 9, 1996). "Winterize Rover for cold-weather fitness, Cornell veterinarian advises; Lessons from the Cornell sled dog team can be applied to house pets". Cornell Science News. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- Schultz, Jeff (1991). Iditarod (2nd ed.). Seattle: Alaska Northwest Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780882404110.

- "Sled Dog Action Coalition - Help Iditarod Sled Dogs". helpsleddogs.org. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- "Ramy Brooks Decision". KTVA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- D'Oro, Rachel (May 25, 2017). "Major Sponsor Pulls Support From Alaska's Iditarod Race". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017.

- "PETA wins as Alaska Airlines backs out of Iditarod race". March 2, 2020.

- Yereth Rosen, "Iditarod Sled-dog Race Losing Exxon Support Amid Animal-rights Pressure," Reuters, 22 January 2021

- "Dallas Seavey Captures 4th Iditarod Crown Record Time". Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "1974 Iditarod Race Results". Iditarod Trail Committee. January 13, 2013.

- "1995 Iditarod Race Results". Iditarod Trail Committee. January 13, 2013.

- "2003 Iditarod Race Results". Iditarod Trail Committee. January 13, 2013.

- Campbell, Mike (March 2, 2009). "Babe will strut her stuff to Nome one last time". Alaska Dispatch News. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- "Iditarod sled dog race increases purse by $50,000". Alaska Dispatch News. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- "Awards". Iditarod Trail Committee. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

References

- Cordes, Kathleen A. (1999). America's National Historic Trails. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 370. ISBN 0-8061-3103-9.

- Schultz, Jeff; Bill Sherwonit (1991). Iditarod: The Great Race to Nome. Alaska Northwest Books. pp. 144. ISBN 0-88240-411-3.

- Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc (March 5, 2005). 2005 Iditarod Mushers. Retrieved March 5, 2005.

- "Champion and record holders". Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- "The Iditarod Trail". Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ""Incredible" dog leads Iditarod victor". CNN. 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

- "Expenses for the Iditarod". Snow Bound Kennels. 2006. Archived from the original on August 31, 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

External links

- Official website

- Sled Dog Action Coalition Facts about Iditarod dog cruelties

- Live GPS Tracking of Race

- Alaskan Dog Race - slideshow by The First Post

- Dogs endure pain, isolation, and neglect at Iditarod kennels - a report by PETA