Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (Irish: Cogadh na Saoirse)[4] or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-military Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and its paramilitary forces the Auxiliaries and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC). It was part of the Irish revolutionary period.

| Irish War of Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Irish revolutionary period | |||||||||

Seán Hogan's flying column of the IRA's 3rd Tipperary Brigade during the war | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Military commanders:

|

Military commanders:

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 491 dead[3] |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

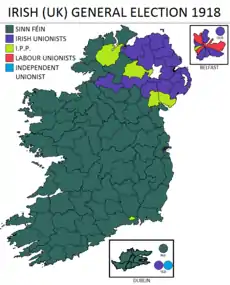

In April 1916, Irish republicans launched the Easter Rising against British rule and proclaimed an Irish Republic. Although it was crushed after a week of fighting, the Rising and the British response led to greater popular support for Irish independence. In the December 1918 election, republican party Sinn Féin won a landslide victory in Ireland. On 21 January 1919 they formed a breakaway government (Dáil Éireann) and declared Irish independence. That day, two RIC officers were killed in the Soloheadbeg ambush by IRA volunteers acting on their own initiative. The conflict developed gradually. For most of 1919, IRA activity involved capturing weaponry and freeing republican prisoners, while the Dáil set about building a state. In September, the British government outlawed the Dáil and Sinn Féin and the conflict intensified. The IRA began ambushing RIC and British Army patrols, attacking their barracks and forcing isolated barracks to be abandoned. The British government bolstered the RIC with recruits from Britain—the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries—who became notorious for ill-discipline and reprisal attacks on civilians,[5] some of which were authorised by the British government.[6] Thus the conflict is sometimes called the "Black and Tan War".[7] The conflict also involved civil disobedience, notably the refusal of Irish railwaymen to transport British forces or military supplies.

In mid-1920, republicans won control of most county councils, and British authority collapsed in most of the south and west, forcing the British government to introduce emergency powers. About 300 people had been killed by late 1920, but the conflict escalated in November. On Bloody Sunday in Dublin, 21 November 1920, fourteen British intelligence operatives were assassinated; then the RIC fired on the crowd at a Gaelic football match, killing fourteen civilians and wounding sixty-five. A week later, the IRA killed seventeen Auxiliaries in the Kilmichael Ambush in County Cork. In December, the British authorities declared martial law in much of southern Ireland, and the centre of Cork city was burnt out by British forces in reprisal for an ambush. Violence continued to escalate over the next seven months, when 1,000 people were killed and 4,500 republicans were interned. Much of the fighting took place in Munster (particularly County Cork), Dublin and Belfast, which together saw over 75 percent of the conflict deaths.[8]

The conflict in north-east Ulster had a sectarian aspect (see The Troubles (1920–1922)). While the Catholic minority there mostly backed Irish independence, the Protestant majority were mostly unionist/loyalist. A mainly-Protestant special constabulary was formed, and loyalist paramilitaries were active. They attacked Catholics in reprisal for IRA actions, and in Belfast a sectarian conflict raged in which almost 500 were killed, most of them Catholics.[9] In May 1921, Ireland was partitioned under British law by the Government of Ireland Act, which created Northern Ireland.

A ceasefire began on 11 July 1921. The post-ceasefire talks led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921. This ended British rule in most of Ireland and, after a ten-month transitional period overseen by a provisional government, the Irish Free State was created as a self-governing Dominion on 6 December 1922. Northern Ireland remained within the United Kingdom. After the ceasefire, violence in Belfast and fighting in border areas of Northern Ireland continued, and the IRA launched a failed Northern offensive in May 1922. In June 1922, disagreement among republicans over the Anglo-Irish Treaty led to the eleven-month Irish Civil War. The Irish Free State awarded 62,868 medals for service during the War of Independence, of which 15,224 were issued to IRA fighters of the flying columns.[10]

Origins of the conflict

Home Rule Crisis

Since the 1870s, Irish nationalists in the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) had been demanding Home Rule, or self-government, from Britain. Fringe organisations, such as Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin, instead argued for some form of Irish independence, but they were in a small minority.[11]

The demand for Home Rule was eventually granted by the British Government in 1912,[12] immediately prompting a prolonged crisis within the United Kingdom as Ulster unionists formed an armed organisation – the Ulster Volunteers (UVF) – to resist this measure of devolution, at least in territory they could control. In turn, nationalists formed their own paramilitary organisation, the Irish Volunteers.[13]

The British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914, known as the Home Rule Act, on 18 September 1914 with an amending Bill for the partition of Ireland introduced by Ulster Unionist MPs, but the Act's implementation was immediately postponed by the Suspensory Act 1914 due to the outbreak of the First World War in the previous month.[14] The majority of nationalists followed their IPP leaders and John Redmond's call to support Britain and the Allied war effort in Irish regiments of the New British Army, the intention being to ensure the commencement of Home Rule after the war.[15] However, a significant minority of the Irish Volunteers opposed Ireland's involvement in the war. The Volunteer movement split, a majority leaving to form the National Volunteers under Redmond. The remaining Irish Volunteers, under Eoin MacNeill, held that they would maintain their organisation until Home Rule had been granted. Within this Volunteer movement, another faction, led by the separatist Irish Republican Brotherhood, began to prepare for a revolt against British rule in Ireland.[16]

Easter Rising

The plan for revolt was realised in the Easter Rising of 1916, in which the Volunteers launched an insurrection whose aim was to end British rule. The insurgents issued the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, proclaiming Ireland's independence as a republic.[17] The Rising, in which over four hundred people died,[18] was almost exclusively confined to Dublin and was put down within a week, but the British response, executing the leaders of the insurrection and arresting thousands of nationalist activists, galvanised support for the separatist Sinn Féin[19] – the party which the republicans first adopted and then took over as well as followers from Countess Markievicz, who was second-in-command of the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Rising.[20] By now, support for the British war effort was waning, and Irish public opinion was shocked and outraged by some of the actions committed by British troops, particularly the murder of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and the imposition of wartime martial law.[21]

First Dáil

In April 1918, the British Cabinet, in the face of the crisis caused by the German spring offensive, attempted with a dual policy to simultaneously link the enactment of conscription into Ireland with the implementation of Home Rule, as outlined in the report of the Irish Convention of 8 April 1918. This further alienated Irish nationalists and produced mass demonstrations during the Conscription Crisis of 1918.[22] In the 1918 general election Irish voters showed their disapproval of British policy by giving Sinn Féin 70% (73 seats out of 105,) of Irish seats, 25 of these uncontested.[23] Sinn Féin won 91% of the seats outside of Ulster on 46.9% of votes cast but was in a minority in Ulster, where unionists were in a majority. Sinn Féin pledged not to sit in the UK Parliament at Westminster, but rather to set up an Irish Parliament.[24] This parliament, known as the First Dáil, and its ministry, called the Aireacht, consisting only of Sinn Féin members, met at the Mansion House on 21 January 1919. The Dáil reaffirmed the 1916 Proclamation with the Irish Declaration of Independence,[25] and issued a Message to the Free Nations of the World, which stated that there was an "existing state of war, between Ireland and England". The Irish Volunteers were reconstituted as the "Irish Republican Army" or IRA.[26] The IRA was perceived by some members of Dáil Éireann to have a mandate to wage war on the British Dublin Castle administration.

Forces

British

.jpg.webp)

The heart of British power in Ireland was the Dublin Castle administration, often known to the Irish as "the Castle".[27] The head of the Castle administration was the Lord Lieutenant, to whom a Chief Secretary was responsible, leading—in the words of the British historian Peter Cottrell—to an "administration renowned for its incompetence and inefficiency".[27] Ireland was divided into three military districts. During the course of the war, two British divisions, the 5th and the 6th, were based in Ireland with their respective headquarters in the Curragh and Cork.[27] By July 1921 there were 50,000 British troops based in Ireland; by contrast there were 14,000 soldiers in metropolitan Britain.[28] While the British Army had historically been heavily dependent on Irish recruitment, concern over divided loyalties led to the redeployment from 1919 of all regular Irish regiments to garrisons outside Ireland itself.[29]

The two main police forces in Ireland were the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Dublin Metropolitan Police.[30] Of the 17,000 policemen in Ireland, 513 were killed by the IRA between 1919 and 1921 while 682 were wounded.[30] Of the RIC's senior officers, 60% were Irish Protestants and the rest Catholic, while 70% of the rank and file of the RIC were Irish Catholic with the rest Protestant.[30] The RIC was trained for police work, not war, and was woefully ill-prepared to take on counter-insurgency duties.[31] Until March 1920, London regarded the unrest in Ireland as primarily an issue for the police and did not regard it as a war.[32] The purpose of the Army was to back up the police. During the course of the war, about a quarter of Ireland was put under martial law, mostly in Munster; in the rest of the country British authority was not deemed sufficiently threatened to warrant it.[28] During the course of the war, the British created two paramilitary police forces to supplement the work of the RIC, recruited mostly from World War I veterans, namely the Temporary Constables (better known as the "Black and Tans") and the Temporary Cadets or Auxiliary Division (known as the "Auxies").[33]

Irish republican

On 25 November 1913, the Irish Volunteers were formed by Eoin MacNeill in response to the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force that had been founded earlier in the year to fight against Home Rule.[34] Also in 1913, the Irish Citizen Army was founded by the trade unionists and socialists James Larkin and James Connolly following a series of violent incidents between trade unionists and the Dublin police in the Dublin lock-out.[35] In June 1914, Nationalist leader John Redmond forced the Volunteers to give his nominees a majority on the ruling committee. When, in September 1914, Redmond encouraged the Volunteers to enlist in the British Army, a faction led by Eoin MacNeill broke with the Redmondites, who became known as the National Volunteers, rather than fight for Britain in the war.[35] Many of the National Volunteers did enlist, and the majority of the men in the 16th (Irish) Division of the British Army had formerly served in the National Volunteers.[36] The Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army launched the Easter Rising against British rule in 1916, when an Irish Republic was proclaimed. Thereafter they became known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Between 1919 and 1921 the IRA claimed to have a total strength of 70,000, but only about 3,000 were actively engaged in fighting against the Crown.[37] The IRA distrusted those Irishmen who had fought in the British Army during the First World War, but there were a number of exceptions such as Emmet Dalton, Tom Barry and Martin Doyle.[37] The basic structure of the IRA was the flying column which could number between 20 and 100 men.[37] Finally, Michael Collins created the "Squad"—gunmen responsible to himself who were assigned special duties such as the assassination of policemen and suspected informers within the IRA.[37]

Course of the war

Pre-war violence

The years between the Easter Rising of 1916 and the beginning of the War of Independence in 1919 were not bloodless. Thomas Ashe, one of the Volunteer leaders imprisoned for his role in the 1916 rebellion, died on hunger strike, after attempted force-feeding in 1917. In 1918, during disturbances arising out of the anti-conscription campaign, six civilians died in confrontations with the police and British Army and more than 1,000 people were arrested. There were also raids for arms by the Volunteers,[38] at least one shooting of a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) policeman and the burning of an RIC barracks in Kerry.[39] The attacks brought a British military presence from the summer of 1918, which only briefly quelled the violence, and an increase in police raids.[40] However, there was as yet no co-ordinated armed campaign against British forces or RIC. In County Cork, four rifles were seized from the Eyeries barracks in March 1918 and men from the barracks were beaten that August.[40] In early July 1918, Volunteers ambushed two RIC men who had been stationed to stop a feis being held on the road between Ballingeary and Ballyvourney in the first armed attack on the RIC since the Easter Rising – one was shot in the neck, the other beaten, and police carbines and ammunition were seized.[40][41] Patrols in Bantry and Ballyvourney were badly beaten in September and October. In November 1918, Armistice Day was marked by severe rioting in Dublin that left over 100 British soldiers injured.[42]

Initial hostilities

While it was not clear in the beginning of 1919 that the Dáil ever intended to gain independence by military means, and war was not explicitly threatened in Sinn Féin's 1918 manifesto,[43] an incident occurred on 21 January 1919, the same day as the First Dáil convened. The Soloheadbeg Ambush, in County Tipperary, was led by Seán Treacy, Séumas Robinson, Seán Hogan and Dan Breen acting on their own initiative. The IRA attacked and shot two RIC officers, Constables James McDonnell and Patrick O'Connell,[44] who were escorting explosives. Breen later recalled:

...we took the action deliberately, having thought over the matter and talked it over between us. Treacy had stated to me that the only way of starting a war was to kill someone, and we wanted to start a war, so we intended to kill some of the police whom we looked upon as the foremost and most important branch of the enemy forces. The only regret that we had following the ambush was that there were only two policemen in it, instead of the six we had expected.[45]

This is widely regarded as the beginning of the War of Independence.[46] The British government declared South Tipperary a Special Military Area under the Defence of the Realm Act two days later.[47] The war was not formally declared by the Dáil, and it ran its course parallel to the Dáil's political life. On 10 April 1919 the Dáil was told:

As regards the Republican prisoners, we must always remember that this country is at war with England and so we must in a sense regard them as necessary casualties in the great fight.[48]

In January 1921, two years after the war had started, the Dáil debated "whether it was feasible to accept formally a state of war that was being thrust on them, or not", and decided not to declare war.[49] Then on 11 March, Dáil Éireann President Éamon de Valera called for acceptance of a "state of war with England". The Dail voted unanimously to empower him to declare war whenever he saw fit, but he did not formally do so.[50]

Violence spreads

Volunteers began to attack British government property, carry out raids for arms and funds and target and kill prominent members of the British administration. The first was Resident Magistrate John C. Milling, who was shot dead in Westport, County Mayo, for having sent Volunteers to prison for unlawful assembly and drilling.[51] They mimicked the successful tactics of the Boers' fast violent raids without uniform. Although some republican leaders, notably Éamon de Valera, favoured classic conventional warfare to legitimise the new republic in the eyes of the world, the more practically experienced Michael Collins and the broader IRA leadership opposed these tactics as they had led to the military débacle of 1916. Others, notably Arthur Griffith, preferred a campaign of civil disobedience rather than armed struggle.[52] The violence used was at first deeply unpopular with Irish people and it took the heavy-handed British response to popularise it among much of the population.[53]

During the early part of the conflict, roughly from 1919 to the middle of 1920, there was a relatively limited amount of violence. Much of the nationalist campaign involved popular mobilisation and the creation of a republican "state within a state" in opposition to British rule. British journalist Robert Lynd wrote in The Daily News in July 1920 that:

So far as the mass of people are concerned, the policy of the day is not active but a passive policy. Their policy is not so much to attack the Government as to ignore it and to build up a new government by its side.[54]

Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as special target

.jpg.webp)

The IRA's main target throughout the conflict was the mainly Irish Catholic Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the British government's armed police force in Ireland, outside Dublin. Its members and barracks (especially the more isolated ones) were vulnerable, and they were a source of much-needed arms. The RIC numbered 9,700 men stationed in 1,500 barracks throughout Ireland.[55]

A policy of ostracism of RIC men was announced by the Dáil on 11 April 1919.[56] This proved successful in demoralising the force as the war went on, as people turned their faces from a force increasingly compromised by association with British government repression.[57] The rate of resignation went up and recruitment in Ireland dropped off dramatically. Often, the RIC were reduced to buying food at gunpoint, as shops and other businesses refused to deal with them. Some RIC men co-operated with the IRA through fear or sympathy, supplying the organisation with valuable information. By contrast with the effectiveness of the widespread public boycott of the police, the military actions carried out by the IRA against the RIC at this time were relatively limited. In 1919, 11 RIC men and 4 Dublin Metropolitan Police G Division detectives were killed and another 20 RIC wounded.[58]

Other aspects of mass participation in the conflict included strikes by organised workers, in opposition to the British presence in Ireland. In Limerick in April 1919, a general strike was called by the Limerick Trades and Labour Council, as a protest against the declaration of a "Special Military Area" under the Defence of the Realm Act, which covered most of Limerick city and a part of the county. Special permits, to be issued by the RIC, would now be required to enter the city. The Trades Council's special Strike Committee controlled the city for fourteen days in an episode that is known as the Limerick Soviet.[59]

Similarly, in May 1920, Dublin dockers refused to handle any war matériel and were soon joined by the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union, who banned railway drivers from carrying members of the British forces. Blackleg train drivers were brought over from England, after drivers refused to carry British troops. The strike badly hampered British troop movements until December 1920, when it was called off.[60] The British government managed to bring the situation to an end, when they threatened to withhold grants from the railway companies, which would have meant that workers would no longer have been paid.[61] Attacks by the IRA also steadily increased, and by early 1920, they were attacking isolated RIC stations in rural areas, causing them to be abandoned as the police retreated to the larger towns.

Collapse of the British administration

In early April 1920, 400 abandoned RIC barracks were burned to the ground to prevent them being used again, along with almost one hundred income tax offices. The RIC withdrew from much of the countryside, leaving it in the hands of the IRA.[62] In June–July 1920, assizes failed all across the south and west of Ireland; trials by jury could not be held because jurors would not attend. The collapse of the court system demoralised the RIC and many police resigned or retired. The Irish Republican Police (IRP) was founded between April and June 1920, under the authority of Dáil Éireann and the former IRA Chief of Staff Cathal Brugha to replace the RIC and to enforce the ruling of the Dáil Courts, set up under the Irish Republic. By 1920, the IRP had a presence in 21 of Ireland's 32 counties.[63] The Dáil Courts were generally socially conservative, despite their revolutionary origins, and halted the attempts of some landless farmers at redistribution of land from wealthier landowners to poorer farmers.[64]

The Inland Revenue ceased to operate in most of Ireland. People were instead encouraged to subscribe to Collins' "National Loan", set up to raise funds for the young government and its army.[65] By the end of the year the loan had reached £358,000. It eventually reached £380,000. An even larger amount, totalling over $5 million, was raised in the United States by Irish Americans and sent to Ireland to finance the Republic.[61] Rates were still paid to local councils but nine out of eleven of these were controlled by Sinn Féin, who naturally refused to pass them on to the British government.[64] By mid-1920, the Irish Republic was a reality in the lives of many people, enforcing its own law, maintaining its own armed forces and collecting its own taxes. The British Liberal journal, The Nation, wrote in August 1920 that "the central fact of the present situation in Ireland is that the Irish Republic exists".[54]

The British forces, in trying to re-assert their control over the country, often resorted to arbitrary reprisals against republican activists and the civilian population. An unofficial government policy of reprisals began in September 1919 in Fermoy, County Cork, when 200 British soldiers looted and burned the main businesses of the town, after one of their number – a soldier of the King's Shropshire Light Infantry who was the first British Army death in the campaign – had been killed in an armed raid by the local IRA[66] on a church parade the day before (7 September). The ambushers were a unit of the No 2 Cork Brigade, under command of Liam Lynch, who wounded four of the other soldiers and disarmed the rest before fleeing in their cars. The local coroner's inquest refused to return a murder verdict over the soldier and local businessmen who had sat on the jury were targeted in the reprisal.[67]

Arthur Griffith estimated that in the first 18 months of the conflict, British forces carried out 38,720 raids on private homes, arrested 4,982 suspects, committed 1,604 armed assaults, carried out 102 indiscriminate shootings and burnings in towns and villages, and killed 77 people including women and children.[68] In March 1920, Tomás Mac Curtain, the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork, was shot dead in front of his wife at his home, by men with blackened faces who were seen returning to the local police barracks. The jury at the inquest into his death returned a verdict of wilful murder against David Lloyd George (the British Prime Minister) and District Inspector Swanzy, among others. Swanzy was later tracked down and killed in Lisburn, County Antrim. This pattern of killings and reprisals escalated in the second half of 1920 and in 1921.[69]

IRA organisation and operations

Michael Collins was a driving force behind the independence movement. Nominally the Minister of Finance in the republic's government and IRA Director of Intelligence, he was involved in providing funds and arms to the IRA units and in the selection of officers. Collins' charisma and organisational capability galvanised many who came in contact with him. He established what proved an effective network of spies among sympathetic members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police's G Division and other important branches of the British administration. The G Division men were a relatively small political division active in subverting the republican movement and were detested by the IRA as often they were used to identify volunteers, who would have been unknown to British soldiers or the later Black and Tans. Collins set up the "Squad", a group of men whose sole duty was to seek out and kill "G-men" and other British spies and agents. Collins' Squad began killing RIC intelligence officers in July 1919.[70] Many G-men were offered a chance to resign or leave Ireland by the IRA. One spy who escaped with his life was F. Digby Hardy, who was exposed by Arthur Griffith before an "IRA" meeting, which in fact consisted of Irish and foreign journalists, and then advised to take the next boat out of Dublin.[71]

The Chief of Staff of the IRA was Richard Mulcahy, who was responsible for organising and directing IRA units around the country. In theory, both Collins and Mulcahy were responsible to Cathal Brugha, the Dáil's Minister of Defence, but, in practice, Brugha had only a supervisory role, recommending or objecting to specific actions. A great deal also depended on IRA leaders in local areas (such as Liam Lynch, Tom Barry, Seán Moylan, Seán Mac Eoin and Ernie O'Malley) who organised guerrilla activity, largely on their own initiative. For most of the conflict, IRA activity was concentrated in Munster and Dublin, with only isolated active IRA units elsewhere, such as in County Roscommon, north County Longford and western County Mayo.

While the paper membership of the IRA, carried over from the Irish Volunteers, was over 100,000 men, Michael Collins estimated that only 15,000 were active in the IRA during the course of the war, with about 3,000 on active service at any time. There were also support organisations Cumann na mBan (the IRA women's group) and Fianna Éireann (youth movement), who carried weapons and intelligence for IRA men and secured food and lodgings for them. The IRA benefitted from the widespread help given to them by the general Irish population, who generally refused to pass information to the RIC and the British military and who often provided "safe houses" and provisions to IRA units "on the run".

Much of the IRA's popularity arose from the excessive reaction of the British forces to IRA activity. When Éamon de Valera returned from the United States, he demanded in the Dáil that the IRA desist from the ambushes and assassinations, which were allowing the British to portray it as a terrorist group and to take on the British forces with conventional military methods. The proposal was immediately dismissed.

Martial law

The British increased the use of force; reluctant to deploy the regular British Army into the country in greater numbers, they set up two auxiliary police units to reinforce the RIC. The first of these, quickly nicknamed as the Black and Tans, were seven thousand strong and mainly ex-British soldiers demobilised after World War I. Deployed to Ireland in March 1920, most came from English and Scottish cities. While officially they were part of the RIC, in reality they were a paramilitary force. After their deployment in March 1920, they rapidly gained a reputation for drunkenness and poor discipline. The wartime experience of most Black and Tans did not suit them for police duties and their violent behavior antagonised many previously neutral civilians.[72]

In response to and retaliation for IRA actions, in the summer of 1920, the Tans burned and sacked numerous small towns throughout Ireland, including Balbriggan,[73] Trim,[74] Templemore[75] and others.

In July 1920, another quasi-military police body, the Auxiliaries, consisting of 2,215 former British army officers, arrived in Ireland. The Auxiliaries had a reputation just as bad as the Tans for their mistreatment of the civilian population but tended to be more effective and more willing to take on the IRA. The policy of reprisals, which involved public denunciation or denial and private approval, was famously satirised by Lord Hugh Cecil when he said: "It seems to be agreed that there is no such thing as reprisals but they are having a good effect."[76]

On 9 August 1920, the British Parliament passed the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act. It replaced the trial by jury by courts-martial by regulation for those areas where IRA activity was prevalent.[77]

On 10 December 1920, martial law was proclaimed in Counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary in Munster; in January 1921 martial law was extended to the rest of Munster in Counties Clare and Waterford, as well as counties Kilkenny and Wexford in Leinster.[78]

It also suspended all coroners' courts because of the large number of warrants served on members of the British forces and replaced them with "military courts of enquiry".[79] The powers of military courts-martial were extended to cover the whole population and were empowered to use the death penalty and internment without trial; Government payments to local governments in Sinn Féin hands were suspended. This act has been interpreted by historians as a choice by Prime Minister David Lloyd George to put down the rebellion in Ireland rather than negotiate with the republican leadership.[80] As a result, violence escalated steadily from that summer and sharply after November 1920 until July 1921. It was in this period that a mutiny broke out among the Connaught Rangers, stationed in India. Two were killed whilst trying to storm an armoury and one was later executed.[81]

Escalation: October–December 1920

.jpg.webp)

A number of events dramatically escalated the conflict in late 1920. First the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, died on hunger strike in Brixton Prison in London in October, while two other IRA prisoners on hunger strike, Joe Murphy and Michael Fitzgerald, died in Cork Jail.

Sunday, 21 November 1920, was a day of dramatic bloodshed in Dublin that became known as Bloody Sunday. In the early morning, Collins' Squad attempted to wipe out leading British intelligence operatives in the capital, in particular the Cairo Gang, killing 16 men (including two cadets, one alleged informer, and one possible case of mistaken identity) and wounding 5 others. The attacks took place at different places (hotels and lodgings) in Dublin.[82]

In response, RIC men drove in trucks into Croke Park (Dublin's GAA football and hurling ground) during a football match, shooting into the crowd. Fourteen civilians were killed, including one of the players, Michael Hogan, and a further 65 people were wounded.[83] Later that day two republican prisoners, Dick McKee, Peadar Clancy and an unassociated friend, Conor Clune who had been arrested with them, were killed in Dublin Castle. The official account was that the three men were shot "while trying to escape", which was rejected by Irish nationalists, who were certain the men had been tortured then murdered.[84]

On 28 November 1920, one week later, the West Cork unit of the IRA, under Tom Barry, ambushed a patrol of Auxiliaries at Kilmichael, County Cork, killing all but one of the 18-man patrol.

These actions marked a significant escalation of the conflict. In response, the counties of Cork, Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary – all in the province of Munster – were put under martial law on 10 December under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act; this was followed on 5 January in the rest of Munster and in counties Kilkenny and Wexford in the province of Leinster.[78] Shortly afterwards, in January 1921, "official reprisals" were sanctioned by the British and they began with the burning of seven houses in Midleton, County Cork.

.jpg.webp)

On 11 December, the centre of Cork City was burnt out by the Black and Tans, who then shot at firefighters trying to tackle the blaze, in reprisal for an IRA ambush in the city on 11 December 1920 which killed one Auxiliary and wounded eleven.[85]

Attempts at a truce in December 1920 were scuppered by Hamar Greenwood, who insisted on a surrender of IRA weapons first.[86]

Peak of violence: December 1920 – July 1921

During the following eight months until the Truce of July 1921, there was a spiralling of the death toll in the conflict, with 1,000 people including the RIC police, army, IRA volunteers and civilians, being killed in the months between January and July 1921 alone.[87] This represents about 70% of the total casualties for the entire three-year conflict. In addition, 4,500 IRA personnel (or suspected sympathisers) were interned in this time.[88] In the middle of this violence, de Valera (as President of Dáil Éireann) acknowledged the state of war with Britain in March 1921.[89]

Between 1 November 1920 and 7 June 1921 twenty-four men were executed by the British.[90] The first IRA volunteer to be executed was Kevin Barry, one of The Forgotten Ten who were buried in unmarked graves in unconsecrated ground inside Mountjoy Prison until 2001.[91] On 1 February, the first execution under martial law of an IRA man took place: Cornelius Murphy, of Millstreet in County Cork, was shot in Cork City. On 28 February, six more were executed, again in Cork.

On 19 March 1921, Tom Barry's 100-strong West Cork IRA unit fought an action against 1,200 British troops – the Crossbarry Ambush. Barry's men narrowly avoided being trapped by converging British columns and inflicted between ten and thirty killed on the British side. Just two days later, on 21 March, the Kerry IRA attacked a train at the Headford junction near Killarney. Twenty British soldiers were killed or injured, as well as two IRA men and three civilians. Most of the actions in the war were on a smaller scale than this, but the IRA did have other significant victories in ambushes, for example at Millstreet in Cork and at Scramogue in Roscommon, also in March 1921 and at Tourmakeady and Carowkennedy in Mayo in May and June. Equally common, however, were failed ambushes, the worst of which, for example at Mourneabbey, Upton and Clonmult in Cork in February 1921, saw six, three, and twelve IRA men killed respectively and more captured. The IRA in Mayo suffered a comparable reverse at Kilmeena, while the Leitrim flying column was almost wiped out at Selton Hill. Fears of informers after such failed ambushes often led to a spate of IRA shootings of informers, real and imagined.

The biggest single loss for the IRA, however, came in Dublin. On 25 May 1921, several hundred IRA men from the Dublin Brigade occupied and burned the Custom House (the centre of local government in Ireland) in Dublin city centre. Symbolically, this was intended to show that British rule in Ireland was untenable. However, from a military point of view, it was a heavy defeat in which five IRA men were killed and over eighty captured.[92] This showed the IRA was not well enough equipped or trained to take on British forces in a conventional manner. However, it did not, as is sometimes claimed, cripple the IRA in Dublin. The Dublin Brigade carried out 107 attacks in the city in May and 93 in June, showing a falloff in activity, but not a dramatic one. However, by July 1921, most IRA units were chronically short of both weapons and ammunition, with over 3,000 prisoners interned.[93] Also, for all their effectiveness at guerrilla warfare, they had, as Richard Mulcahy recalled, "as yet not been able to drive the enemy out of anything but a fairly good sized police barracks".[94]

Still, many military historians have concluded that the IRA fought a largely successful and lethal guerrilla war, which forced the British government to conclude that the IRA could not be defeated militarily.[95] The failure of the British efforts to put down the guerrillas was illustrated by the events of "Black Whitsun" on 13–15 May 1921. A general election for the Parliament of Southern Ireland was held on 13 May. Sinn Féin won 124 of the new parliament's 128 seats unopposed, but its elected members refused to take their seats. Under the terms of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, the Parliament of Southern Ireland was therefore dissolved, and executive and legislative authority over Southern Ireland was effectively transferred to the Lord Lieutenant (assisted by Crown appointees). Over the next two days (14–15 May), the IRA killed fifteen policemen. These events marked the complete failure of the British Coalition Government's Irish policy—both the failure to enforce a settlement without negotiating with Sinn Féin and a failure to defeat the IRA.

By the time of the truce, however, many republican leaders, including Michael Collins, were convinced that if the war went on for much longer, there was a chance that the IRA campaign as it was then organised could be brought to a standstill. Because of this, plans were drawn up to "bring the war to England". The IRA did take the campaign to the streets of Glasgow.[96] It was decided that key economic targets, such as the Liverpool docks, would be bombed. The units charged with these missions would more easily evade capture because England was not under, and British public opinion was unlikely to accept, martial law. These plans were abandoned because of the truce.

Truce: July–December 1921

The war of independence in Ireland ended with a truce on 11 July 1921. The conflict had reached a stalemate. Talks that had looked promising the previous year had petered out in December when David Lloyd George insisted that the IRA first surrender their arms. Fresh talks, after the Prime Minister had come under pressure from H. H. Asquith and the Liberal opposition, the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress, resumed in the spring and resulted in the Truce. From the point of view of the British government, it appeared as if the IRA's guerrilla campaign would continue indefinitely, with spiralling costs in British casualties and in money. More importantly, the British government was facing severe criticism at home and abroad for the actions of British forces in Ireland. On 6 June 1921, the British made their first conciliatory gesture, calling off the policy of house burnings as reprisals. On the other side, IRA leaders and in particular Michael Collins, felt that the IRA as it was then organised could not continue indefinitely. It had been hard pressed by the deployment of more regular British soldiers to Ireland and by the lack of arms and ammunition.

The initial breakthrough that led to the truce was credited to three people: King George V, Prime Minister of South Africa General Jan Smuts and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom David Lloyd George. The King, who had made his unhappiness at the behaviour of the Black and Tans in Ireland well known to his government, was dissatisfied with the official speech prepared for him for the opening of the new Parliament of Northern Ireland, created as a result of the partition of Ireland. Smuts, a close friend of the King, suggested to him that the opportunity should be used to make an appeal for conciliation in Ireland. The King asked him to draft his ideas on paper. Smuts prepared this draft and gave copies to the King and to Lloyd George. Lloyd George then invited Smuts to attend a British cabinet meeting consultations on the "interesting" proposals Lloyd George had received, without either man informing the Cabinet that Smuts had been their author. Faced with the endorsement of them by Smuts, the King and Lloyd George, the ministers reluctantly agreed to the King's planned 'reconciliation in Ireland' speech.

The speech, when delivered in Belfast on 22 June, was universally well received. It called on "all Irishmen to pause, to stretch out the hand of forbearance and conciliation, to forgive and to forget, and to join in making for the land they love a new era of peace, contentment, and good will."[97]

On 24 June 1921, the British Coalition Government's Cabinet decided to propose talks with the leader of Sinn Féin. Coalition Liberals and Unionists agreed that an offer to negotiate would strengthen the Government's position if Sinn Féin refused. Austen Chamberlain, the new leader of the Unionist Party, said that "the King's Speech ought to be followed up as a last attempt at peace before we go the full lengths of martial law".[98] Seizing the momentum, Lloyd George wrote to Éamon de Valera as "the chosen leader of the great majority in Southern Ireland" on 24 June, suggesting a conference.[99] Sinn Féin responded by agreeing to talks. De Valera and Lloyd George ultimately agreed to a truce that was intended to end the fighting and lay the ground for detailed negotiations. Its terms were signed on 9 July and came into effect on 11 July. Negotiations on a settlement, however, were delayed for some months as the British government insisted that the IRA first decommission its weapons, but this demand was eventually dropped. It was agreed that British troops would remain confined to their barracks.

Most IRA officers on the ground interpreted the Truce merely as a temporary respite and continued recruiting and training volunteers. Nor did attacks on the RIC or British Army cease altogether. Between December 1921 and February of the next year, there were 80 recorded attacks by the IRA on the soon to be disbanded RIC, leaving 12 dead.[100] On 18 February 1922, Ernie O'Malley's IRA unit raided the RIC barracks at Clonmel, taking 40 policemen prisoner and seizing over 600 weapons and thousands of rounds of ammunition.[101] In April 1922, in the Dunmanway killings, an IRA party in Cork killed 10 local suspected Protestant informers in retaliation for the shooting of one of their men. Those killed were named in captured British files as informers before the Truce signed the previous July.[102] Over 100 Protestant families fled the area after the killings.

Treaty

.jpg.webp)

Ultimately, the peace talks led to the negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty (6 December 1921), which was then ratified in triplicate: by Dáil Éireann on 7 January 1922 (so giving it legal legitimacy under the governmental system of the Irish Republic), by the House of Commons of Southern Ireland in January 1922 (so giving it constitutional legitimacy according to British theory of who was the legal government in Ireland), and by both Houses of the British parliament.[103][104]

The treaty allowed Northern Ireland, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, to opt out of the Free State if it wished, which it duly did on 8 December 1922 under the procedures laid down. As agreed, an Irish Boundary Commission was then created to decide on the precise location of the border of the Free State and Northern Ireland.[105] The republican negotiators understood that the commission would redraw the border according to local nationalist or unionist majorities. Since the 1920 local elections in Ireland had resulted in outright nationalist majorities in County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, the City of Derry and in many district electoral divisions of County Armagh and County Londonderry (all north and west of the "interim" border), this might well have left Northern Ireland unviable. However, the Commission chose to leave the border unchanged; as a trade-off, the money owed to Britain by the Free State under the Treaty was not demanded.

A new system of government was created for the new Irish Free State, though for the first year two governments co-existed; an Dáil Ministry headed by President Griffith, and a Provisional Government nominally answerable to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland and appointed by the Lord Lieutenant.[106]

Most of the Irish independence movement's leaders were willing to accept this compromise, at least for the time being, though many militant republicans were not. A majority of the pre-Truce IRA who had fought in the War of Independence, led by Liam Lynch, refused to accept the Treaty and in March 1922 repudiated the authority of the Dáil and the new Free State government, which it accused of betraying the ideal of the Irish Republic. It also broke the Oath of Allegiance to the Irish Republic which the Dáil had instated on 20 August 1919.[107] The anti-treaty IRA were supported by the former president of the Republic, Éamon de Valera, and ministers Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack.[108]

.jpg.webp)

St. Mary's Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, August 1922

While the violence in the North was still raging, the South of Ireland was preoccupied with the split in the Dáil and in the IRA over the treaty. In April 1922, an executive of IRA officers repudiated the treaty and the authority of the Provisional Government which had been set up to administer it. These republicans held that the Dáil did not have the right to disestablish the Irish Republic. A hardline group of Anti-Treaty IRA men occupied several public buildings in Dublin in an effort to bring down the treaty and restart the war with the British. There were a number of armed confrontations between pro and anti-treaty troops before matters came to a head in late June 1922.[104] Desperate to get the new Irish Free State off the ground and under British pressure, Michael Collins attacked the anti-treaty militants in Dublin, causing fighting to break out around the country.[104]

The subsequent Irish Civil War lasted until mid-1923 and cost the lives of many of the leaders of the independence movement, notably the head of the Provisional Government Michael Collins, ex-minister Cathal Brugha, and anti-treaty republicans Harry Boland, Rory O'Connor, Liam Mellows, Liam Lynch and many others: total casualties have never been determined but were perhaps higher than those in the earlier fighting against the British. President Arthur Griffith also died of a cerebral haemorrhage during the conflict.[109]

Following the deaths of Griffith and Collins, W. T. Cosgrave became head of government. On 6 December 1922, following the coming into legal existence of the Irish Free State, W. T. Cosgrave became President of the Executive Council, the first internationally recognised head of an independent Irish government.

The civil war ended in mid-1923 in defeat for the anti-treaty side.[110]

North-east

The conflict in the north-east had a sectarian aspect. While Ireland as a whole had an Irish nationalist and Catholic majority, Unionists and Protestants were a majority in the north-east, largely due to 17th century British colonization. These Ulster Unionists wanted to maintain ties to Britain and did not want to be part of an independent Ireland. They had threatened to oppose Irish home rule with violence. The British government proposed to solve this by partitioning Ireland on roughly political and religious lines, creating two self-governing territories of the UK: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Irish nationalists opposed this, most of them supporting the all-island Irish Republic.

The IRA carried out attacks on British forces in the north-east, but was less active than in the south. Protestant loyalists attacked the Catholic community in reprisal. There were outbreaks of sectarian violence from June 1920 to June 1922, influenced by political and military events. Most of it was in the city of Belfast, which saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence between Protestants and Catholics.[111] In the Belfast violence, Hibernians were more involved on the Catholic/nationalist side than the IRA,[112] while groups such as the Ulster Volunteers were involved on the Protestant/loyalist side. There was rioting, gun battles and bombings. Almost 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed and people were expelled from workplaces and mixed neighbourhoods. More than 500 were killed[113] and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.[114] The British Army was deployed and the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) was formed to help the regular police. The USC was almost wholly Protestant and some of its members carried out reprisal attacks on Catholics.[115] Conflict continued in Northern Ireland after the July 1921 truce; both communal violence in Belfast and guerrilla conflict in rural border areas.[116]

Irish nationalists argued that the violence around Belfast was a pogrom against Catholics/nationalists, as Catholics were a quarter of the city's population but made up two-thirds of those killed, suffered 80% of the property destruction and made up 80% of refugees.[113] Historian Alan Parkinson says the term 'pogrom' is misleading, as the violence was not all one-sided nor co-ordinated.[117] The Irish government estimated that 50,000 left Northern Ireland permanently due to violence and intimidation.[118]

Summer 1920

While the IRA was less active in the north-east than in the south, Ulster unionists saw themselves as besieged by Irish republicans. The January and June 1920 local elections saw Irish nationalists and republicans win control of many northern urban councils, as well as Tyrone and Fermanagh county councils. Derry City had its first Irish nationalist and Catholic mayor.[119]

Fighting broke out in Derry on 18 June 1920 and lasted a week. Catholic homes were attacked in the mainly-Protestant Waterside, and Catholics fled by boat across the Foyle while coming under fire. In the Cityside, Loyalists fired from the Fountain neighbourhood into Catholic streets, while the IRA occupied St Columb's College and returned fire. At least fourteen Catholics and five Protestants were killed in the violence.[120] Eventually, 1,500 British troops were deployed in Derry and imposed a curfew.[121]

On 17 July, British Colonel Gerald Smyth was assassinated by the IRA in Cork. He had told police officers to shoot civilians who did not immediately obey orders.[122] Smyth came from Banbridge, County Down. Loyalists retaliated by attacking many Catholic homes and businesses in Banbridge and expelling Catholics from their jobs, forcing many to flee the town.[123] There were similar attacks in nearby Dromore.[124]

On 21 July, loyalists drove 8,000 "disloyal" co-workers from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards, all of them either Catholics or Protestant labour activists. Some were viciously attacked.[125] This was partly in response to recent IRA actions and partly because of competition over jobs due to high unemployment. It was fuelled by rhetoric from Unionist politicians. In his Twelfth of July speech, Edward Carson had called for loyalists to take matters into their own hands, and had linked republicanism with socialism and the Catholic Church.[126] The expulsions sparked fierce sectarian rioting in Belfast, and British troops fired machine-guns to disperse rioters. Eleven Catholics and eight Protestants were killed and hundreds wounded.[125] Catholic workers were soon driven out of all major Belfast factories. In response, the Dáil approved the 'Belfast Boycott' of Unionist-owned businesses and banks in the city. It was enforced by the IRA, who halted trains and lorries and destroyed goods.[127]

On 22 August, the IRA assassinated RIC Inspector Oswald Swanzy as he left church in Lisburn. Swanzy had been implicated in the killing of Cork Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain. In revenge, loyalists burned and looted hundreds of Catholic businesses and homes in Lisburn, forcing many Catholics to flee (see the Burnings in Lisburn). As a result, Lisburn was the first town to recruit special constables. After some of them were charged with rioting, their colleagues threatened to resign, and they were not prosecuted.[128]

.jpg.webp)

In September, Unionist leader James Craig wrote to the British government demanding that a special constabulary be recruited from the ranks of the Ulster Volunteers. He warned, "Loyalist leaders now feel the situation is so desperate that unless the Government will take immediate action, it may be advisable for them to see what steps can be taken towards a system of organised reprisals against the rebels".[129] The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) was formed in October and, in the words of historian Michael Hopkinson, "amounted to an officially approved UVF".[130]

Spring–summer 1921

.jpg.webp)

After a lull in violence in the north, the conflict there intensified again in spring 1921. In February, as reprisal for the shooting of a Special Constable, USC and UVF men burned ten Catholic homes and a priest's house in Rosslea, County Fermanagh.[131] The following month, the IRA attacked the homes of sixteen Special Constables in the Rosslea district, killing three and wounding others.[132]

The 'Act of Partition' came into force on 3 May 1921.[133] That month, James Craig secretly met Éamon de Valera in Dublin. They discussed the possibility of a truce in Ulster and an amnesty for prisoners. Craig proposed a compromise of limited independence for the South and autonomy for the North within the UK. The talks came to nothing and violence in the north continued.[134] Elections to the Northern parliament were held on 24 May, in which Unionists won most seats. Its parliament first met on 7 June and formed a devolved government, headed by Craig. Republican and nationalist members refused to attend. King George V addressed the ceremonial opening of the Northern parliament on 22 June.[133] The next day, a train carrying the king's armed escort, the 10th Royal Hussars, was derailed by an IRA bomb at Adavoyle, County Armagh. Five soldiers and a train guard were killed, as were fifty horses. A civilian bystander was also shot dead by British soldiers.[135]

Loyalists condemned the truce as a 'sell-out' to republicans.[136] On 10 July, a day before the ceasefire was to begin, police launched a raid against republicans in west Belfast. The IRA ambushed them on Raglan Street, killing an officer. This sparked a day of violence known as Belfast's Bloody Sunday. Protestant loyalists attacked Catholic enclaves in west Belfast, burning homes and businesses. This led to sectarian clashes between Protestants and Catholics, and gun battles between police and nationalists. The USC allegedly drove through Catholic enclaves firing indiscriminately.[137] Twenty people were killed or fatally wounded (including twelve Catholics and six Protestants) before the truce began at noon on 11 July.[138] After the truce came into effect on 11 July, the USC was demobilized (July - November 1921). The void left by the demobilized USC was filled by loyalist vigilante groups and a revived UVF.[139]

There were further outbreaks of violence in Belfast after the truce. Twenty people were killed in street fighting and assassinations from 29 August to 1 September 1921 and another thirty were killed from 21 to 25 November. Loyalists had by this time taken to throwing bombs randomly into Catholic streets and the IRA responded by bombing trams carrying Protestant workmen.[140]

Early 1922

Despite the Dáil's acceptance of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January 1922, which confirmed the future existence of Northern Ireland, there were clashes between the IRA and British forces along the new border from early 1922. In part, this reflected Michael Collins' view that the Treaty was a "stepping stone", rather than a final settlement. That month, Collins became head of the new Irish Provisional Government and the Irish National Army was founded, though the IRA continued to exist.[141]

In January 1922, members of the Monaghan Gaelic football team were arrested by Northern police on their way to a match in Derry. Among them were IRA volunteers with plans to free IRA prisoners from Derry prison. In response, on the night of 7–8 February, IRA units crossed the border and captured almost fifty Special Constables and prominent loyalists in Fermanagh and Tyrone. They were to be held as hostages for the Monaghan prisoners. Several IRA volunteers were also captured during the raids.[142] This operation had been approved by Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Frank Aiken and Eoin O'Duffy.[143] The Northern Ireland authorities responded by sealing-off many cross-border roads.[144]

The months of February and March 1922 saw levels of violence in the north that had not been seen before. Between 11 February and 31 March, 51 Catholics were killed with 115 wounded, with 32 Protestants killed and 86 wounded.[145] On 11 February, IRA volunteers stopped a group of armed Special Constables at Clones railway station, County Monaghan. The USC unit was travelling by train from Belfast to Enniskillen (both in Northern Ireland), but the Provisional Government was unaware British forces would be crossing through its territory. The IRA called on the Specials to surrender for questioning, but one of them shot dead an IRA sergeant. This sparked a firefight in which four Specials were killed and several wounded. Five others were captured.[146] The incident threatened to set off a major confrontation between North and South, and the British government temporarily suspended the withdrawal of British troops from the South. A Border Commission was set up to mediate in any future border disputes, but achieved very little.[147]

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_801289.jpg.webp)

These incidents provoked retaliation attacks by loyalists against Catholics in Belfast, sparking further sectarian clashes. In the three days after the Clones incident, more than 30 people were killed in the city, including four Catholic children and two women who were killed by a loyalist grenade on Weaver Street.[147]

On 18 March, Northern police raided IRA headquarters in Belfast, seizing weapons and lists of IRA volunteers. The Provisional Government condemned this as a breach of the truce.[148] Over the next two weeks, the IRA raided several police barracks in the North, killed several officers and captured fifteen.[148][149]

On 24 March, six Catholics were shot dead by Special Constables who broke into the home of the McMahon family (see McMahon killings). This was in revenge for the IRA killing of two policemen.[150] A week later, six more Catholics were killed by Specials in another revenge attack known as the Arnon Street massacre.[151]

Winston Churchill had arranged a meeting between Collins and James Craig on 21 January and the southern boycott of Belfast goods was lifted but then re-imposed after several weeks. The two leaders had further meetings, but despite a joint declaration that "peace is declared" on 30 March, violence continued.[152]

Summer 1922: Northern offensive

In May 1922 the IRA launched a Northern Offensive, secretly backed by Michael Collins, head of the Irish Provisional Government. By this time, the IRA was split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty, but both pro and anti-treaty units were involved. Some weaponry sent by the British to arm the National Army were in fact given to IRA units and their weapons sent to the North.[153] However, the offensive was a failure. An IRA Belfast Brigade report in late May concluded that continuing the offensive was "futile and foolish" and would "place the Catholic population at the mercy of the Specials".[154]

On 22 May, after the assassination of West Belfast Unionist MP William Twaddell, the Northern government introduced internment and 350 IRA men were arrested in Belfast, crippling its organisation there.[155] The biggest clash of the IRA offensive was the Battle of Pettigo and Belleek, which ended with British troops using artillery to dislodge around 100 IRA volunteers from the border villages of Pettigo and Belleek, killing three volunteers. This was the last major confrontation between the IRA and British forces during the revolutionary period.[156] The cycle of sectarian violence in Belfast continued. May saw 75 people killed in Belfast and another 30 in June. Several thousand Catholics fled the violence and sought refuge in Glasgow and Dublin.[157] On 17 June, in revenge for the killing of two Catholics by Specials, Frank Aiken's IRA unit shot dead six Protestant civilians in Altnaveigh, south Armagh. Three Specials were also ambushed and killed.[158]

Collins held British Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson (MP for North Down) responsible for the attacks on Catholics in the north and may have been behind his assassination in June 1922, though who ordered the shooting is unproven.[159] The event helped to trigger the Irish Civil War. Winston Churchill insisted after the killing that Collins take action against the Anti-Treaty IRA, whom he assumed to be responsible.[160] The outbreak of civil war in the South ended the violence in the North, as the war demoralised the northern IRA and diverted the organisation from the issue of partition. The Irish Free State quietly ended Collins' policy of covert armed action in Northern Ireland.

The violence in the north fizzled out by late 1922.[161]

Detention

Ballykinlar internment camp was the first mass internment camp in Ireland during the Irish War of Independence holding almost 2,000 men.[162] Ballykinlar gained a reputation for brutality: three prisoners were shot dead and five died from maltreatment.[163] At HM Prison Crumlin Road in Belfast, Cork County Gaol (see 1920 Cork hunger strike) and Mountjoy jail in Dublin some of the political prisoners went on hunger strike. In 1920 two Irish republicans died as a result of hunger strikes - Michael Fitzgerald d. 17 October 1920 and Joe Murphy d. 25 October 1920.[164]

Conditions during internment were not always good - during the 1920s, the vessel HMS Argenta was moored in Belfast Lough and used as a prison ship for the holding of Irish Republicans by the British government after Bloody Sunday. Cloistered below decks in cages which held 50 internees, the prisoners were forced to use broken toilets which overflowed frequently into their communal area. Deprived of tables, the already weakened men ate off the floor, frequently succumbing to disease and illness as a result. There were several hunger strikes on the Argenta, including a major strike involving upwards of 150 men in the winter of 1923.[165]

Killing of alleged spies

In recent decades, attention has been drawn to the IRA's shooting of civilian informers in the south. Several historians, notably Peter Hart have alleged that those killed in this manner were often simply considered "enemies" rather than being proven informers. Especially vulnerable, it is argued, were Protestants, ex-soldiers and tramps. "It was not merely (or even mainly) a matter of espionage, spies and spy hunters, it was a civil war between and within communities".[166] Particularly controversial in this regard has been the Dunmanway killings of April 1922, when ten Protestants were killed and three disappeared over two nights. Hart's contentions have been challenged by a number of historians, notably Niall Meehan[167] and Meda Ryan.[168]

Propaganda war

The Irish tricolour which dated back to the Young Ireland rebellion of 1848.

The standard of the Lord Lieutenant, using the union flag created under the Act of Union 1800.

Another feature of the war was the use of propaganda by both sides.[169]

The British government also collected material on the liaison between Sinn Féin and Soviet Russia, in an unsuccessful attempt to portray Sinn Féin as a crypto-communist movement.[170]

The Catholic Church hierarchy was critical of the violence of both sides, but especially that of the IRA, continuing a long tradition of condemning militant republicanism. The Bishop of Kilmore, Dr. Finnegan, said: "Any war... to be just and lawful must be backed by a well grounded hope of success. What hope of success have you against the mighty forces of the British Empire? None... none whatever and if it unlawful as it is, every life taken in pursuance of it is murder."[171] Thomas Gilmartin, the Archbishop of Tuam, issued a letter saying that IRA men who took part in ambushes "have broken the truce of God, they have incurred the guilt of murder."[172] However, in May 1921, Pope Benedict XV dismayed the British government when he issued a letter that exhorted the "English as well as Irish to calmly consider . . . some means of mutual agreement", as they had been pushing for a condemnation of the rebellion.[173] They declared that his comments "put HMG (His Majesty's Government) and the Irish murder gang on a footing of equality".[173]

Desmond FitzGerald and Erskine Childers were active in producing the Irish Bulletin, which detailed government atrocities which Irish and British newspapers were unwilling or unable to cover. It was printed secretly and distributed throughout Ireland, and to international press agencies and US, European and sympathetic British politicians.

While the military war made most of Ireland ungovernable from early 1920, it did not actually remove British forces from any part. But the success of Sinn Féin's propaganda campaign reduced the option of the British government to deepen the conflict; it worried in particular about the effect on British relations with the US, where groups like the American Committee for Relief in Ireland had so many eminent members. The British cabinet had not sought the war that had developed since 1919. By 1921 one of its members, Winston Churchill, reflected:

What was the alternative? It was to plunge one small corner of the empire into an iron repression, which could not be carried out without an admixture of murder and counter-murder.... Only national self-preservation could have excused such a policy, and no reasonable man could allege that self-preservation was involved.[174]

Casualties

According to The Dead of the Irish Revolution, 2,346 people were killed or died as a result of the conflict. This counts a small number of deaths before and after the war, from 1917 until the signing of the Treaty at the end of 1921. Of those killed, 919 were civilians, 523 were police personnel, 413 were British military personnel, and 491 were IRA volunteers[3] (although another source gives 550 IRA dead).[175] About 44% of these British military deaths were by misadventure (such as accidental shooting) and suicide while on active service, as were 10% of police losses and 14% of IRA losses.[176] About 36% of police personnel who died were born outside Ireland.[176]

At least 557 people were killed in political violence in what became Northern Ireland between July 1920 and July 1922. Many of these deaths took place after the truce that ended fighting in the rest of Ireland. Of these deaths, between 303 and 340 were Catholic civilians, between 172 and 196 were Protestant civilians, 82 were police personnel (38 RIC and 44 USC), and 35 were IRA volunteers. Most of the violence took place in Belfast: at least 452 people were killed there – 267 Catholics and 185 Protestants.[177]

Post-war evacuation of British forces

By October 1921 the British Army in Ireland numbered 57,000 men, along with 14,200 RIC police and some 2,600 auxiliaries and Black and Tans. The long-planned evacuation from dozens of barracks in what the army called "Southern Ireland" started on 12 January 1922, following the ratification of the Treaty and took nearly a year, organised by General Nevil Macready. It was a huge logistical operation, but within the month Dublin Castle and Beggars Bush Barracks were transferred to the Provisional Government. The RIC last paraded on 4 April and was formally disbanded on 31 August. By the end of May the remaining forces were concentrated in Dublin, Cork and Kildare. Tensions that led to the Irish Civil War were evident by then and evacuation was suspended. By November about 6,600 soldiers remained in Dublin at 17 locations. Finally on 17 December 1922 The Royal Barracks (now housing collections of the National Museum of Ireland) was transferred to General Richard Mulcahy and the garrison embarked at Dublin Port that evening.[178]

Compensation

In May 1922 the British Government with the agreement of the Irish Provisional Government established a commission chaired by Lord Shaw of Dunfermline to examine compensation claims for material damage caused between 21 January 1919 and 11 July 1921.[179] The Irish Free State's Damage To Property (Compensation) Act, 1923 provided that only the Shaw Commission, and not the Criminal Injury Acts, could be used to claim compensation.[180] Originally, the British government paid claims from unionists and the Irish government those from nationalists; claims from "neutral" parties were shared.[181] After the 1925 collapse of the Irish Boundary Commission, the UK, Free State and Northern Ireland governments negotiated revisions to the 1921 treaty; the Free State stopped contributing to the servicing of the UK national debt, but took over full responsibility for compensation for war damage, with the fund increased by 10% in 1926.[182] The Compensation (Ireland) Commission worked until March 1926, processing thousands of claims.[181]

Role of women in the war

Although most of the fighting was carried out by men, women played a substantial supporting role in the Irish War of Independence. Before the Easter Rising of 1916, many Irish nationalist women were brought together through organisations fighting for women's suffrage, such as the Irish Women's Franchise League.[183] The republican socialist Irish Citizen Army promoted gender equality and many of these women—including Constance Markiewicz, Madeleine ffrench-Mullen, and Kathleen Lynn—joined the group.[184] In 1914, the all-female paramilitary group Cumann na mBan was launched as an auxiliary of the Irish Volunteers. During the Easter Rising, some women participated in fighting and carried messages between Irish Volunteer posts while being shot at by British troops.[185] After the rebel defeat, Éamon de Valera opposed the participation of women in combat and they were limited to supporting roles.[186]

During the conflict, women hid IRA volunteers being sought by the British, nursed wounded volunteers, and gathered money to help republican prisoners and their families. Cumann na mBan engaged in undercover work to set back the British war effort. They smuggled guns, ammunition, and money to the IRA; Kathleen Clarke smuggled gold worth £2,000 from Limerick to Dublin for Michael Collins.[187] Because they sheltered wanted men, many women were subject to raids on their homes by British police and soldiers, with acts of sexual violence sometimes being reported but not confirmed.[186] It is estimated that there were between 3,000 and 9,000 members of Cumann na mBan during the war, and in 1921 there were 800 branches throughout the island. It is estimated that fewer than 50 women were imprisoned by the British during the war.[187]

Memorial

A memorial called the Garden of Remembrance was erected in Dublin in 1966, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising. The date of signing of the truce is commemorated by the National Day of Commemoration, when all those Irish men and women who fought in wars in specific armies (e.g., the Irish unit(s) fighting in the British Army in 1916 at the Battle of the Somme) are commemorated.

The last survivor of the conflict, Dan Keating (of the IRA), died in October 2007 at the age of 105.[188]

Cultural depictions

Literature

- 1923 – The Shadow of a Gunman, play by Seán O'Casey

- 1929 – The Last September, novel by Elizabeth Bowen

- 1931 – Guests of the Nation, short story by Frank O'Connor

- 1970 – Troubles, novel by J. G. Farrell

- 1979 – The Old Jest, novel by Jennifer Johnston, winner of the Whitbread Award

- 1991 - "Amongst Women", novel by John McGahern

- 2010 – The Soldier's Song, novel by Alan Monaghan

Television and film

- 1926 – Irish Destiny, silent film

- 1929 – The Informer, part-talkie film

- 1934 – The Key, American Pre-Code film

- 1935 – The Informer, John Ford film

- 1936 – The Dawn, Irish film (also called Dawn Over Ireland)

- 1936 – Ourselves Alone, British film

- 1936 – Beloved Enemy, American drama film

- 1937 – The Plough and the Stars, John Ford film

- 1959 – Shake Hands with the Devil, feature film

- 1975 – Days of Hope, 1916: Joining Up

- 1988 – The Dawning, film, based on Jennifer Johnston's The Old Jest

- 1989 – The Shadow of Béalnabláth (1989) RTÉ TV Documentary by Colm Connolly about the life and death of Michael Collins.

- 1991 – The Treaty

- 1996 – Michael Collins, feature film

- 1999 – The Last September (film)

- 2001 – Rebel Heart, BBC miniseries. The theme music of the same name was composed by Sharon Corr.

- 2002 – An Deichniúr Dearmadta (The Forgotten Ten) a TG4 TV Documentary

- 2006 – The Wind That Shakes the Barley, feature film

- 2014 – A Nightingale Falling, film

- 2019 – Resistance, five-part RTÉ miniseries

See also

- Aftermath of World War I

- Revolutions of 1917–1923

- The Troubles

References

- Kautt, William H. (1999). The Anglo-Irish War, 1916–21: A People's War. Praeger Publishers. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-275-96311-8.; Hoyt, Timothy D. (2009). "Why Ireland Won: The War from the Irish Side". Finest Hour. International Churchill Society. 143: 55. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Costello, Francis J. (January 1989). "The Role of Propaganda in the Anglo-Irish War 1919–1921". The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies. 14 (2): 5–24. JSTOR 25512739. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- Eunan O'Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin. The Dead of the Irish Revolution. Yale University Press, 2020. p.544

- Heatherly, Christopher J. (2012). Cogadh Na Saoirse: British Intelligence Operations During the Anglo-Irish War, 1916–1921 (reprint ed.). BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781249919506. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Dinan, Brian (1987). Clare and its people. Dublin: The Mercier Press. p. 105. ISBN 085342-828-X.

- Coleman, Marie (2013). The Irish Revolution, 1916–1923. Routledge. pp. 86–87.

- "The Black and Tan War – Nine Fascinating Facts About the Bloody Fight for Irish Independence". Militaryhistorynow.com. 9 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2018.; "Irishmedals.org". Irishmedals.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.; "Michael Collins: A Man Against an Empire". HistoryNet. 12 June 2006. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Eunan O'Halpin on the Dead of the Irish Revolution". Theirishistory.com. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- O'Halpin, Eunan (2012). "Counting Terror". In Fitzpatrick, David (ed.). Terror in Ireland. p. 152.

- Richardson, Neil (2010). A Coward if I return, a Hero if I fall: Stories of Irishmen in World War I. Dublin: O'Brien. p. 13.

- "Ireland – The rise of Fenianism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Government of Ireland Bill". api.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Ireland – The 20th-century crisis". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Coleman, Marie. (2013). The Irish Revolution, 1916–1923. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-317-80147-4. OCLC 864414854.

- "BBC – John Redmond". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- O’Riordan, Tomás: UCC Multitext Project in Irish History John Redmond Archived 28 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "BBC – The Proclamation". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- 1916 Necrology Archived 14 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Glasnevin Trust Archived 5 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- "BBC – Sinn Féin". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Countess Markievicz—'The Rebel Countess'" (PDF). Irish Labour History Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "BBC – The rise of Sinn Féin". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "'A Declaration of War on the Irish People' The Conscription Crisis of 1918". The Irish Story. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Election 1918 – what you need to know about how Ireland voted". rte.ie. 11 December 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.; O'Toole, Fintan. "Fintan O'Toole: The 1918 election was an amazing moment for Ireland". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "The End of the British Empire in Ireland". Public Record Office, The National Archives. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Kautt, William Henry (1999). The Anglo-Irish War, 1916–1921: A People's War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 131. ISBN 978-0275963118. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

And Whereas the Irish Republic was proclaimed in Dublin on Easter Monday, 1916, by the Irish Republican Army acting on behalf of the Irish people...Now, therefore, we, the elected Representatives of the ancient Irish people in National Parliament assembled, do, in the name of the Irish nation, ratify the establishment of the Irish Republic...

- "BBC – The Irish Volunteer Force/Irish Republican Army". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Cottrell, Peter The Anglo-Irish War The Troubles of 1913–1922, London: Osprey, 2006 p. 18.