Jacobaea vulgaris

Jacobaea vulgaris, syn. Senecio jacobaea,[2] is a very common wild flower in the family Asteraceae that is native to northern Eurasia, usually in dry, open places, and has also been widely distributed as a weed elsewhere.

| Jacobaea vulgaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Jacobaea |

| Species: | J. vulgaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Jacobaea vulgaris Gaertn. | |

| Synonyms[1][2][3] | |

|

Senecio jacobaea L. | |

Common names include ragwort, common ragwort,[4] stinking willie,[5] tansy ragwort, benweed, St. James-wort, stinking nanny/ninny/willy, staggerwort, dog standard, cankerwort, stammerwort. In the western United States it is generally known as tansy ragwort, or tansy, though its resemblance to the true tansy is superficial.

In some countries it is an invasive species and regarded as a noxious weed. In the UK, where it is native, it is often unwanted because of its toxic effect for cattle and horses, but it is also valued for its nectar production which feeds insect pollinators and its ecological importance is thus considered significant.

Description

The plant is generally considered to be biennial but it has the tendency to exhibit perennial properties under certain cultural conditions (such as when subjected to repeated grazing or mowing).[6] The stems are erect, straight, have no or few hairs, and reach a height of 0.3–2.0 metres (1 ft 0 in – 6 ft 7 in). The leaves are pinnately lobed and the end lobe is blunt.[7] The many names that include the word "stinking" (and Mare's Fart) arise because of the unpleasant smell of the leaves. The hermaphrodite flower heads are 1.5–2.5 centimetres (0.59–0.98 in) diameter, and are borne in dense, flat-topped clusters; the florets are bright yellow. It has a long flowering period lasting from June to November (in the Northern Hemisphere).

Pollination is by a wide range of bees, flies and moths and butterflies. Over a season, one plant may produce 2,000 to 2,500 yellow flowers in 20- to 60-headed, flat-topped corymbs. The achenes have dandelion-like groups of prickly hairs called pappuses, which help seed dispersal by the wind.[8][9] The number of seeds produced may be as large as 75,000 to 120,000, although in its native range in Eurasia very few of these would grow into new plants and research has shown that most seeds do not travel a great distance from the parent plant.[10][11]

Taxonomy

Two subspecies are accepted:

- Jacobaea vulgaris ssp. vulgaris - the typical plant, with ray florets present.

- Jacobaea vulgaris ssp. dunensis - the ray florets are missing.

Distribution

Ragwort is native to the Eurasian continent. In Europe it is widely spread, from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. In Britain and Ireland, where it is native it is listed as a noxious weed.[12]

Ragwort is abundant in waste land, waysides and grazing pastures.[13] It can be found along road sides, and grows in all cool and high rainfall areas.

It has been introduced in many other regions, and is listed as a weed in many. These include:

- North America: The United States, present mainly in the northwest and northeast: California, Idaho, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington;

- South America: Argentina;

- Africa: North Africa;

- Asia: India and Siberia;

- Australasia: a widespread weed in New Zealand and Australia.

Ecological importance

Although the plant is often unwanted by landowners because of its toxic effect for cattle and horses, and because it is considered a weed by many, it provides a great deal of nectar for pollinators. It was rated in the top 10 for most nectar production (nectar per unit cover per year) in a UK plants survey conducted by the AgriLand project which is supported by the UK Insect Pollinators Initiative.[14] It also was the top producer of nectar sugar in another study in Britain, with a production per floral unit of (2921 ± 448μg).[15]

In the United Kingdom, where the plant is native, ragwort provides a home and food source to at least 77 insect species. Thirty of these species of invertebrate use ragwort exclusively as their food source[16] and there are another 22 species where ragwort forms a significant part of their diet.

English Nature identifies a further 117 species that use ragwort as a nectar source whilst travelling between feeding and breeding sites, or between metapopulations.[16] These consist mainly of solitary bees, hoverflies, moths, and butterflies such as the small copper butterfly (Lycaena phlaeas). Pollen is collected by solitary bees.[17]

Besides the fact that ragwort is very attractive to such a vast array of insects, some of these are very rare indeed. Of the 30 species that specifically feed on ragwort alone, seven are officially deemed nationally scarce. A further three species are on the IUCN Red List. In short, ragwort is an exclusive food source for ten rare or threatened insect species, including the cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae),[18] the picture winged fly (Campiglossa malaris), the scarce clouded knot horn moth (Homoeosoma nimbella), and the Sussex emerald moth (Thalera fimbrialis).[16] The Sussex Emerald has been labelled a Priority Species in the United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan. A priority species is one which is "scarce, threatened and declining".[19] The remainder of the ten threatened species include three species of leaf beetle, another picture-winged fly, and three micro moths. All of these species are Nationally Scarce B, with one leaf beetle categorised as Nationally Scarce A.[16]

The most common of those species that are totally reliant on ragwort for their survival is the cinnabar moth. The cinnabar is a United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan Species, its status described as "common and widespread, but rapidly declining".[19]

Poisonous effects

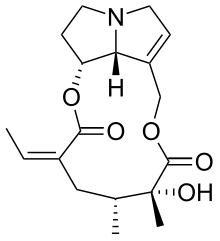

Ragwort contains many different alkaloids, making it poisonous to certain animals. (EHC 80,section 9.1.4). Alkaloids which have been found in the plant confirmed by the WHO report EHC 80 are -- jacobine, jaconine, jacozine, otosenine, retrorsine, seneciphylline, senecionine, and senkirkine (p. 322 Appendix II). There is a strong variation between plants from the same location in distribution between the possible alkaloids and even the absolute amount of alkaloids varies drastically.[20]

Ragwort is of concern to people who keep horses and cattle.[21][22] In areas of the world where ragwort is a native plant, such as Britain and continental Europe, documented cases of proven poisoning are rare.[23] Horses do not normally eat fresh ragwort due to its bitter taste. The result, if sufficient quantity is consumed, can be irreversible cirrhosis of the liver of a form identified as megalocytosis where cells are abnormally enlarged. Signs that a horse has been poisoned include yellow mucous membranes, depression, and lack of coordination.

There is no definitive test for the poisoning however, since megalocytosis is not a change in the liver which is specific to ragwort poisoning. It is also seen in poisoning by other alkylating agents, such as nitrosamines and aflatoxins.[24] Aflatoxins are a common contaminant formed in feedstuffs by moulds. Research in the United Kingdom has produced results showing megalocytosis, which may be due to various causes, to be a relatively uncommon cause of liver disease in horses.[25]

The alkaloid does not actually accumulate in the liver but a breakdown product can damage DNA and progressively kills cells. About 3-7% of the body weight is sometimes claimed as deadly for horses, but an example in the scientific literature exists of a horse surviving being fed over 20% of its body weight. The effect of low doses is lessened by the destruction of the original alkaloids by the action of bacteria in the digestive tract before they reach the bloodstream. There is no known antidote or cure to poisoning, but examples are known from the scientific literature of horses making a full recovery once consumption has been stopped.[26][27]

The alkaloids can be absorbed in small quantities through the skin but studies have shown that the absorption is very much less than by ingestion. Also some are in the N-oxide form which only becomes toxic after conversion inside the digestive tract and they will be excreted harmlessly.

Some sensitive individuals can suffer from an allergic reaction because ragwort, like many members of the family Compositae, contains sesquiterpene lactones which can cause compositae dermatitis. These are different from the pyrrolizidine alkaloids which are responsible for the toxic effects.

Honey collected from ragwort has been found to contain small quantities of jacoline, jacobine, jacozine, senecionine, and seneciphylline, but the quantities have been judged as too minute to be of concern.[28]

Control

As indicated above, common ragwort has become a problem in several areas in which it has been introduced, and various methods are employed to help prevent its spread.

In many Australian states ragwort has been declared a noxious weed, and landholders are required to remove it from their property by law. In the island state of Tasmania, ragwort is responsible for more than half of the total costs of that state's control of invasive species. The species has been calculated as the 8th most expensive invasive species in terms of cost to Australian farmers, at over A$half a billion over 60 years.[29]

It is also legislated as a noxious weed in New Zealand, where farmers sometimes bring in helicopters to spray their farms if the ragwort is too widespread.

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, the Noxious Weeds (Thistle, Ragwort, and Dock) Order 1937, issued under the Noxious Weeds Act 1936, declares ragwort as a noxious weed, requiring landowners to control its growth.[30][31]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, common ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) is one of the five plants named as an injurious weed under the provisions of the Weeds Act 1959. The word injurious in this context indicates that it could be harmful to agriculture, not that it is dangerous to animals, as all the other injurious weeds listed are non-toxic. Under the terms of this Act, a land occupier can be required by the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to prevent the spread of the plant. However, the growth of the plant is not made illegal by the Act and there is no statutory obligation for control placed upon landowners in general.[32]

The Ragwort Control Act 2003 provides for a code of practice, which the government states is guidance,[33] on ragwort and does not place any further legal responsibilities on landowners to control the plant.[34]

Biological control

Ragwort is a food plant for the larvae of Cochylis atricapitana, Phycitodes maritima, and Phycitodes saxicolais. Ragwort is best known as the food of caterpillars of the cinnabar moth Tyria jacobaeae. They absorb alkaloids from the plant and become distasteful to predators, a fact advertised by the black and yellow warning colours. The red and black, day-flying adult moth is also distasteful to many potential predators. The moth is used as a control for ragwort in countries in which it has been introduced and become a problem, like New Zealand and the western United States.[35] As both larvae and adults are distinctly colored and marked, identification of cinnabars is easy outside of their natural range, and grounds and range keepers can quickly recognize them. In both countries, the tansy ragwort flea beetle (Longitarsus jacobaeae) has been introduced to combat the plant. Another beetle, Longitarsus ganglbaueri, also feeds on ragwort, but will feed on other plants as well, making it an unsuitable biological control.[36] Another biological control agent introduced in the western United States is the ragwort seed fly, although it is not considered very effective at controlling ragwort.[37] The biological control of ragwort was already used in the 1930s.[38]

Other usage

In ancient Greece and Rome a supposed aphrodisiac was made from the plant; it was called satyrion.

The leaves can be used to obtain a good green dye, although it fades. The flowers can be used to produce a dye that is yellow when the fabric is mordanted with alum. Brown and orange dyes are also reported.[39]

Literature, poetry and mythology

The Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides (c.40-90 CE) recommended the herb. The two "fathers" of herbalism, Gerard and Culpeper, also recommended the herb. Culpeper was an astrological botanist and thought the plant was "under the command of Dame Venus, and [it] cleanses, digests, and discusses."[40]

The poet John Clare had a more positive opinion of the plant, as revealed in this poem of 1831:

- Ragwort thou humble flower with tattered leaves

- I love to see thee come and litter gold...

- Thy waste of shining blossoms richly shields

- The sun tanned sward in splendid hues that burn

- So bright and glaring that the very light

- Of the rich sunshine doth to paleness turn

- And seems but very shadows in thy sight.

The ragwort, under its Manx name Cushag, is the national flower of the Isle of Man[41] According to one story King Orry chose as his emblem the cushag flower, as its twelve petals represent one of the isles of the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles: the Isle of Man, Arran, Bute, Islay, Jura, Mull, Iona, Eigg, Rum, Skye, Raasay, and the Outer Hebrides. The ragwort, in fact, usually has thirteen petals. The Manx poet Josephine Kermode (1852–1937) wrote the following poem about the Cushag:

- Now, the Cushag, we know,

- Must never grow,

- Where the farmer's work is done.

- But along the rills,

- In the heart of the hills,

- The Cushag may shine like the sun.

- Where the golden flowers,

- Have fairy powers,

- To gladden our hearts with their grace.

- And in Vannin Veg Veen,

- In the valleys green,

- The Cushags have still a place.

(Vannin Veg Veen is Manx for dear little Isle of Man.)

Donald Macalastair of Druim-a-ghinnir on the Isle of Arran told a story of the fairies journeying to Ireland. The ragwort was their transport and every one of them picked a plant, sat astride and arrived in Ireland in an instant.[42]

See also

- List of plants poisonous to equines

- List of Lepidoptera that feed on Senecio

- Cichorieae, a tribe also in the family Asteraceae with similar looking genera (Agoseris, Leontodon, Sonchus, etc)

- Cineraria, a genus also in the tribe Senecioneae with similar looking species

- Senecio vulgaris

References

- "Senecio jacobaea". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- UniProt. "Species Senecio jacobaea". Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- "Jacobaea vulgaris Gaertn". International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; Australian National Botanic Gardens. 29 June 2008.

- BSBI List 2007 (xls). Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Senecio jacobaea". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Howatt, Stephen (1989). "The Toxicity of Tansy Ragwort". Weed Technology. 3 (2): 436–438. doi:10.1017/S0890037X00032115.

- ref name=Parnell and Curtis, T. 2012 Webb's An Irish FloraCork University Press ISBN 978-185918-4783

- BMP: TANSY RAGWORT (Senecio jacobaea) by The WeedWise Program

- Ragwort - Control and removal advice by The Donkey Sanctuary

- Poole, A. L.; Cairns, D. (1940). "Botanical Aspects of Ragwort (Senecio jacobaea L.) Control". Bulletin of the New Zealand Department of Science and Industrial Research. 82: 1–66.

- McEvoy, Peter B.; Cox, Caroline S. (1987). "Wind Dispersal Distances in Dimorphic Achenes of Ragwort, Senecio Jacobaea". Ecology. 68 (6): 2006–2015. doi:10.2307/1939891. JSTOR 1939891. PMID 29357152.

- "Seven of the most invasive plants in the UK". 13 July 2020.

- Clapham, A. R.; Tutin, T. G.; Warburg, E. F. (1968). Excursion flora of the British Isles (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-04656-5.

- "Which flowers are the best source of nectar?". Conservation Grade. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Hicks, DM; Ouvrard, P; Baldock, KCR (2016). "Food for Pollinators: Quantifying the Nectar and Pollen Resources of Urban Flower Meadows". PLOS ONE. 11 (6): e0158117. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1158117H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0158117. PMC 4920406. PMID 27341588.

- "Ragwort Fact File". Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- Wood, Thomas J.; Holland, John M.; Goulson, Dave (2016). "Providing foraging resources for solitary bees on farmland: current schemes for pollinators benefit a limited suite of species" (PDF). Journal of Applied Ecology. 54: 323–333. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12718.

- "Common caterpillars: A simple guide". countrylife.co.uk. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Butterfly Conservation 2007. The United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan - moths. The United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan Archived 2012-05-07 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 2011

- Macel, Mirka; Vrieling, Klaas; Klinkhamer, Peter G. L. (April 2004). "Variation in pyrrolizidine alkaloid patterns of Senecio jacobaea". Phytochemistry. 65 (7): 865–873. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.02.009. PMID 15081286.

- Cortinovis, Cristina; Caloni, Francesca (2015). "Alkaloid-Containing Plants Poisonous to Cattle and Horses in Europe". Toxins. 7 (12): 5301–7. doi:10.3390/toxins7124884. PMC 4690134. PMID 26670251.

- Wiedenfeld, H (2011). "Plants containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids: Toxicity and problems" (PDF). Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. 28 (3): 282–292. doi:10.1080/19440049.2010.541288. PMID 21360374. S2CID 23218347.

- Giles, C. J (1983). "Outbreak of ragwort (Senecio jacobea) poisoning in horses". Equine Veterinary Journal. 15 (3): 248–50. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1983.tb01781.x. PMID 6136403.

- Jubb, K. V. F.; Kennedy, P. C.; Palmer, N. (2007). Pathology of Domestic Animals (5th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 9780702028236.

- Durham, A. E. (2015). "Surveillance focus: Ragwort toxicity in horses in the UK". Veterinary Record. 176 (24): 620–622. doi:10.1136/vr.h2817. PMID 26067012. S2CID 8833710.

- De Lanux-Van Gorder, V. (2000). "Tansy ragwort poisoning in a horse in southern Ontario". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 41 (5): 409–10. PMC 1476261. PMID 10816838.

- Lessard, P.; Wilson, W. D.; Olander, H. J.; Rogers, Q. R.; Mendel, V. E. (1986). "Clinicopathologic study of horses surviving pyrrolizidine alkaloid (Senecio vulgaris) toxicosis". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 47 (8): 1776–80. PMID 2875683.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1995), Surveillance for pyrrolizidine alkaloids in honey, UK Food Standards Agency, archived from the original on 8 August 2007, retrieved 12 August 2007

- Khan, Jo (29 July 2021). "Invasive species have cost Australia $390 billion in the past 60 years, study shows". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- Ragwort in Ireland

- Leiss, Kirsten A (2010). "Management practices for control of ragwort species". Phytochemistry Reviews. 10 (1): 153–163. doi:10.1007/s11101-010-9173-1. PMC 3047715. PMID 21475410.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Weeds Act 1959, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, archived from the original on 12 September 2007, retrieved 12 August 2007

- "Ragwort Control Act 2003 Question for Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs". Hansard.

- Revised text of the Ragwort Control Act 2003 from Legislation.gov.uk. Accessed on 9 December 2011.

- McEvoy, Peter; Cox, Caroline; Coombs, Eric (1991). "Successful Biological Control of Ragwort, Senecio Jacobaea, by Introduced Insects in Oregon". Ecological Applications. 1 (4): 430–442. doi:10.2307/1941900. JSTOR 1941900. PMID 27755672. S2CID 21701854.

- D. A. McLAREN, J. E. IRESON, and R. M. KWONG (2000). "Biological Control of Ragwort (Senecio jacobaea L.) in Australia". Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds: 67–79.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Support, Extension Web (12 June 2018). "Tansy Ragwort". Ag - Weed Management.

- Cameron, Ewen (1935). "A Study of the Natural Control of Ragwort (Senecio Jacobaea L.)". The Journal of Ecology. 23 (2): 265–322. doi:10.2307/2256123. JSTOR 2256123.

- "Senecio jacobaea - L." Plants For A Future. PFAF Charity. Retrieved 14 August 2020.. Cites references at "Plants For A Future Species Database Bibliography". Plants For A Future. PFAF Charity. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 2.

- "Island Facts - Isle of Man Government -". www.gov.im. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007.

- Wentz, W. Y. (1911). The Fairy-faith in Celtic countries (1981 reprint ed.). Colin Smythe. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-901072-51-1.

External links

- Plume moth working to control ragwort in NZ

- Environmental Health Criteria 80 Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids World Health Organisation—the full text of the report is available.

- Ragwort myths and facts This website is the English version of a Dutch ragwort website

- Ragwort Facts.com Information on ragwort in the United Kingdom from a scientific perspective

- Buglife's ragwort pages Information on the importance of ragwort to wildlife on the Buglife website

- The Merck Veterinary Manual introduction to pyrrolizidine alkaloidosis

- Pieter B., Pelser; Gravendeel, Barbara; van der Meijden, Ruud (2002). "Tackling speciose genera: species composition and phylogenetic position of Senecio sect. Jacobaea (Asteraceae) based on plastid and nrDNA sequences". American Journal of Botany. 89 (6): 929–939. doi:10.3732/ajb.89.6.929. PMID 21665692.