Jeju Island

Jeju Island (Korean: 제주도; Hanja: 濟州島; IPA: [tɕeːdzudo]) is South Korea's largest island, covering an area of 1,833.2 km2 (707.8 sq mi), which is 1.83 percent of the total area of the country. It is also the most populous island in South Korea; at the end of September 2020, the total resident registration population of Jeju Special Self-Governing Province is 672,948, of which 4,000 reside on outlying islands such as the Chuja Islands and Udo Island. The total area of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province is 1,849 km.[2]

Native name: 제주도 Nickname: Sammudo, Samdado ("Island of Three Lacks and Three Abundances") | |

|---|---|

Satellite image of Jeju Island | |

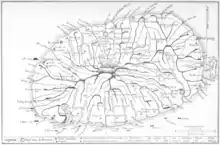

Map of Jeju Island | |

Jeju Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | East Asia |

| Coordinates | 33.38°N 126.53°E |

| Archipelago | Jeju |

| Area | 1,826[1] km2 (705 sq mi) |

| Length | 73 km (45.4 mi) |

| Width | 31 km (19.3 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,950 m (6400 ft) |

| Highest point | Hallasan |

| Administration | |

South Korea | |

| Special Autonomous Province | Jeju Special Autonomous Province |

| Largest settlement | Jeju City (pop. 501,791) |

North Korea (claimed) | |

| Province | South Chŏlla Province |

| County-level division | Cheju Island (further divided into 1 ŭp and 12 myŏn) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 695,519 (2020) |

| Pop. density | 316/km2 (818/sq mi) |

| Languages | Jeju, Korean |

| Ethnic groups | Jejuans, Korean |

| Jeju Island | |

| Hangul | 제주도 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 濟州島 |

| Revised Romanization | Jejudo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chejudo |

The island lies in the Korea Strait, south of the Korean Peninsula, and South Jeolla Province. It is located 82.8 km (51.4 mi) off the nearest point on the peninsula.[3] Jeju is the only self-governing province in South Korea, meaning that the province is run by local inhabitants instead of politicians from the mainland.

Jeju Island has an oval shape of 73 km (45 mi) east–west and 31 km (19 mi) north–south, with a gentle slope around Mt. Halla in the center. The length of the main road is 181 km (112 mi) and the coastline is 258 km (160 mi). The northern end of Jeju Island is Kimnyeong Beach, the southern end is Songak Mountain, the western end is Suwolbong, and the eastern end is Seongsan Ilchulbong.

The island was "formed by the eruption of an underwater volcano approximately 2 million years ago".[4] It contains a natural World Heritage Site, the Jeju Volcanic Island and Lava Tubes.[5] Jeju Island has a temperate climate which is moderate; even in winter, the temperature rarely falls below 0 °C (32 °F). Jeju is a popular holiday destination and a sizable portion of the economy relies on tourism and related economic activity.

Etymology

Historically, the island has been called by many different names including:

- Doi (Hangul: 도이, hanja: 島夷, literally "Island barbarian")

- Dongyeongju (Hangul: 동영주; hanja: 東瀛州)

- Juho (Hangul: 주호, hanja: 州胡)

- Tammora (탐모라, 耽牟羅)

- Seomna (섭라, 涉羅)

- Tangna (탁라, 乇羅)

- Tamna (탐라, 耽羅)

- Quelpart,[6][7][8] Quelparte[9] or Quelpaert Island[10]

- Junweonhado (준원하도, 준원下島 meaning "southern part of peninsula")

- Taekseungnido (Hangul: 택승리도, meaning "the peaceful hot island in Joseon")

- Samdado (Hangul: 삼다도, meaning "Island of Three Abundances")[11]

Before the Japanese annexation in 1910, the island was usually known as Quelpart (Quelpaërt, Quelpaert) to Europeans;[12] during the occupation it was known by the Japanese name Saishū. The name Quelpart coming from French language is attested in Dutch no later than 1648 and may have denoted the first Dutch ship to spot the island, the quelpaert de Brack around 1642, or rather some visual similarity of the island from some angle to this class of ships (a small dispatch vessel, also called a galiot).

The first European explorers to sight the island, the Portuguese, called it Ilha de Ladrones (Island of Thieves).[13]

The name "Fungma island" appeared in the "Atlas of China" of M. Martini who arrived in China as a missionary in 1655.[14]

Logo

The script in the official Jeju logo is colored black, to evoke the basalt of the island, indicating that Jeju's traditions should be preserved and developed. The green symbolizes the natural environment of Mt. Halla and Jeju, blue symbolizes the sea of Jeju, and orange symbolizes the hopeful future and value of Jeju Special Self-Governing Province.[15]

History

The earliest known Polity on the island was the kingdom of Tamna.[16]

After Mongol invasions of Korea, the Mongol Empire established a base on Jeju Island with its ally, the Goryeo army in (Tamna prefectures) and converted part of the island to a grazing area for the Korean and Mongol cavalry stationed there.[17]

In the beginning of the 15th century, Jeju Island was subjected to the highly centralized rule of the Joseon dynasty. A travel ban was implemented for almost 200 years and many uprisings by Jeju Island residents were suppressed.[18]

Jeju uprising

From 3 April 1948 to May 1949, the South Korean government conducted an anticommunist campaign to suppress an attempted uprising on the island.[19][20] The main cause for the rebellion was the election scheduled for 10 May 1948, designed by the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) to create a new government for all of Korea. The elections were only planned for the south of the country, the half of the peninsula under UNTCOK control. Fearing that the elections would further reinforce division, guerrilla fighters of the Workers' Party of South Korea (WPSK) reacted violently, attacking local police and rightist youth groups stationed on Jeju Island.[20][21]

In 2008, bodies of victims of a massacre were discovered in a mass grave near Jeju International Airport.[22]

Refugees on Jeju Island

In 2018, 500 refugees fleeing the civil war in Yemen came to Jeju Island, causing unease and racial tensions among the residents of Jeju Island.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Planned Kim Jong-Un visit

On 11 November 2018, it was announced that preparations were being made for North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un to visit Jeju during his upcoming visit to South Korea.[29] Kim would be transported to Jeju via helicopter.[29] The announcement came in after 200 tonnes of tangerines harvested in Jeju were flown to North Korea as a sign of appreciation for nearly 2 tonnes of North Korean mushrooms Kim gave to South Korea as a gift, following the September 2018 inter-Korean summit.[30][31]

Archaeology

In November 2020, South Korean archeologists announced the discovery of a 900-year-old lost slipway off the coast of Sinchangli. Researchers also discovered bright objects, coins and ceramics belonging to the Northern Song Dynasty.[32]

Geography

Baengnokdam in Hallasan

Baengnokdam in Hallasan.jpg.webp) Mountains in Jeju

Mountains in Jeju Halla Mountain in Jeju

Halla Mountain in Jeju Map including Jeju Island

Map including Jeju Island

Jeju is a volcanic island, dominated by Hallasan: a volcano 1,950 metres (6,400 ft) high and the highest mountain in South Korea. The island measures approximately 73 kilometres (45 mi) across, east to west, and 41 kilometres (25 mi) from north to south.[33]

The island formed by volcanic eruptions approximately two million years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch.[34] The island consists chiefly of basalt and lava.

An area covering about 12% (224 square kilometres or 86 square miles) of Jejudo is known as Gotjawal Forest.[35] This area remained uncultivated until the 21st century, as its base of 'a'a lava made it difficult to develop for agriculture. Because this forest remained pristine for so long, it has a unique ecology.[36]

The forest is the main source of groundwater and thus the main water source for the half million people of the island, because rainwater penetrates directly into the aquifer through the cracks of the 'a'a lava under the forest. Gotjawal forest is considered an internationally important wetland under the Ramsar Convention by some researchers[37] because it is the habitat of unique species of plants and is the main source of water for the residents, although to date it has not been declared a Ramsar site.[38]

.jpg.webp)

Formation

- About 2 million years ago, the island of Jeju was formed through volcanic activity.[34]

- About 1.2 million years ago, a magma chamber formed under the sea floor and began to erupt.

- About 700 thousand years ago, the island had been formed through volcanic activity. Volcanic activity then stopped for approximately 100 thousand years.

- About 300 thousand years ago, volcanic activity restarted along the coastline.

- About 100 thousand years ago, volcanic activity formed Halla Mountain.

- About 25 thousand years ago, lateral eruptions around Halla Mountain left multiple oreum (smaller 'parasitic' cones on the flanks of the primary cone).

- Volcanic activity stopped and prolonged weathering and erosion helped shape the island.[39]

Climate

Jeju has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification). Four distinct seasons are experienced on Jeju; winters are cool with moderate rainfall, while summers are hot and humid with very high rainfall.

In January 2016, a cold wave affected the region. Snow and frigid weather forced the cancellation of 1,200 flights on Jejudo, stranding approximately 90,300 passengers.[40]

| Climate data for Ildo 1-dong, Jeju City (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1923–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

28.1 (82.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.5 (99.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

30.1 (86.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.8 (60.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.5 (2.66) |

57.2 (2.25) |

90.6 (3.57) |

89.7 (3.53) |

95.6 (3.76) |

171.2 (6.74) |

210.2 (8.28) |

272.3 (10.72) |

227.8 (8.97) |

95.1 (3.74) |

69.5 (2.74) |

55.6 (2.19) |

1,502.3 (59.15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12.2 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 11.7 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 11.2 | 6.7 | 9.8 | 11.5 | 127.8 |

| Average snowy days | 7.2 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 5.3 | 18.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.0 | 63.3 | 63.2 | 64.8 | 68.4 | 77.9 | 78.3 | 76.2 | 73.7 | 66.4 | 65.0 | 64.1 | 68.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.2 | 110.0 | 166.0 | 196.5 | 212.2 | 159.7 | 189.8 | 195.1 | 158.9 | 173.3 | 123.7 | 79.1 | 1,834.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22.2 | 34.0 | 42.8 | 49.8 | 49.2 | 39.7 | 44.7 | 47.2 | 43.5 | 50.7 | 40.2 | 27.4 | 41.7 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration (percent sunshine 1981–2010)[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Gosan-ri, Hangyeong-myeon, Jeju City (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1988–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

35.5 (95.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

35.5 (95.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.3 (84.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.4 (79.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.2 (20.8) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40.6 (1.60) |

47.8 (1.88) |

76.2 (3.00) |

94.7 (3.73) |

117.7 (4.63) |

158.1 (6.22) |

167.7 (6.60) |

201.9 (7.95) |

120.4 (4.74) |

56.9 (2.24) |

60.2 (2.37) |

40.7 (1.60) |

1,182.9 (46.57) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10.6 | 9.0 | 10.2 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 13.1 | 9.6 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 10.4 | 119 |

| Average snowy days | 5.9 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 14.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.9 | 68.0 | 69.9 | 74.2 | 80.2 | 86.2 | 89.2 | 83.9 | 77.8 | 69.7 | 67.9 | 66.5 | 75.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 95.4 | 131.0 | 175.4 | 196.3 | 205.3 | 156.0 | 172.6 | 219.7 | 187.4 | 206.6 | 150.7 | 106.3 | 2,002.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 28.7 | 40.7 | 45.0 | 50.3 | 46.9 | 36.8 | 40.4 | 52.0 | 50.5 | 58.8 | 48.9 | 34.9 | 44.7 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration (snow and percent sunshine 1981–2010)[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Jeongbang-dong, Seogwipo (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1961–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

34.8 (94.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.8 (51.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

7.2 (45.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 60.7 (2.39) |

77.9 (3.07) |

130.3 (5.13) |

187.0 (7.36) |

223.6 (8.80) |

267.6 (10.54) |

275.8 (10.86) |

315.7 (12.43) |

208.8 (8.22) |

100.4 (3.95) |

86.2 (3.39) |

55.6 (2.19) |

1,989.6 (78.33) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.8 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 12.8 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 10.9 | 5.8 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 125.3 |

| Average snowy days | 3.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 10.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 63.0 | 62.5 | 62.4 | 65.2 | 70.6 | 80.7 | 86.1 | 80.9 | 73.6 | 64.8 | 64.7 | 63.2 | 69.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 153.5 | 157.4 | 185.8 | 196.5 | 203.5 | 136.3 | 144.8 | 187.7 | 174.7 | 208.8 | 166.8 | 158.8 | 2,074.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 48.0 | 49.2 | 46.9 | 48.9 | 46.3 | 33.6 | 32.5 | 44.5 | 47.4 | 58.8 | 54.3 | 52.1 | 46.2 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration (percent sunshine 1981–2010)[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Seongsan-eup, Seogwipo (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1971–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.9 (69.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

36.2 (97.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

3.9 (39.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 77.5 (3.05) |

83.2 (3.28) |

139.4 (5.49) |

161.3 (6.35) |

178.0 (7.01) |

231.9 (9.13) |

271.3 (10.68) |

343.2 (13.51) |

248.6 (9.79) |

114.0 (4.49) |

102.8 (4.05) |

78.8 (3.10) |

2,030 (79.92) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11.0 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 125.4 |

| Average snowy days | 6.1 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 14.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.4 | 65.5 | 65.4 | 67.4 | 72.2 | 82.6 | 85.6 | 81.5 | 76.3 | 69.4 | 68.7 | 67.7 | 72.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 128.6 | 145.5 | 181.5 | 198.0 | 208.7 | 141.1 | 160.3 | 192.6 | 167.2 | 192.0 | 156.7 | 134.7 | 2,006.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 38.7 | 47.3 | 45.8 | 49.4 | 47.7 | 33.8 | 35.9 | 44.0 | 44.5 | 55.0 | 49.6 | 42.1 | 44.2 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration (snow and percent sunshine 1981–2010)[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Seongpanak, Hallasan (elevation: 760 m (2,490 ft), 1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

1.9 (35.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.6 (45.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 137.1 (5.40) |

182.4 (7.18) |

258.8 (10.19) |

414.9 (16.33) |

465.9 (18.34) |

451.7 (17.78) |

583.9 (22.99) |

717.0 (28.23) |

581.1 (22.88) |

237.2 (9.34) |

197.5 (7.78) |

153.5 (6.04) |

4,381 (172.48) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13.0 | 11.5 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 14.1 | 17.8 | 18.7 | 15.6 | 9.2 | 11.6 | 13.4 | 157.8 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration[41] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Witse Oreum, Hallasan (elevation: 1,672 m (5,486 ft), 2003–2009 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

0.9 (33.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.9 (21.4) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.1 (15.6) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 46.9 (1.85) |

128.0 (5.04) |

301.2 (11.86) |

426.1 (16.78) |

653.1 (25.71) |

651.9 (25.67) |

742.3 (29.22) |

836.4 (32.93) |

526.7 (20.74) |

126.5 (4.98) |

165.8 (6.53) |

64.6 (2.54) |

4,669.4 (183.83) |

| Source: Jeju Regional Meteorological Administration[44] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Tourism is an important component of the local economy. The island is sometimes called "South Korea’s Hawaii". Tourists from China do not require a visa to visit Jeju, unlike the rest of South Korea, and in the 2010s have started visiting on specialised package tours to acquire a South Korean driver's license; the test is similar to that in China, but can be completed in less time and is easier, application and test forms are available in many languages, and a South Korean license, unlike a Chinese license, makes the holder eligible for an International Drivers License.[45]

Tourism

In 1962, the South Korean government established the Korean National Tourism Corporation (KNTC) to monitor and regulate internal and external tourism, and it was later renamed the Korean National Tourism Organization (KNTO).[46] While Korea lacks abundant natural resources, tourism is an entity that generates income nationwide for South Korea. In Jeju-do province, specifically, tourism has proven to be beneficial and has been a growing contributor to the economy.[4] Jeju Island, often compared to Hawaii, “is the winter destination for Asian tourist seeking warm weather and beautiful beaches.”[47]

The island is home to 660,000 people, but hosts 15,000,000 visitors per year.[48] English is not widely spoken in Jeju, and as a matter of fact, “the local dialect is different enough from Korean that it is recognized as a distinct language.”[49] “Until recently, Chinese travelers accounted for 80% of foreign travelers;”[49] however, due to the installation of THAAD (The Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) system in Korea, Chinese travel has dwindled drastically. “THAAD is supposed to shield against North Korean missiles”[50] however China views it as a security threat. Though in the past year [2017] tourism has declined sharply, visits to Jeju continue to be a vacation destination for Asia. There are no visa requirements for visitors staying up to 90 days[4] and future plans to build a second international airport have been discussed. Due to the decline of visitors caused by China's travel ban to Korea due to the concern of THAAD, talks and discussions continue to be held regarding a second airport to service over 45 million people with an anticipated completion by 2035.[49] The current Jeju International Airport is crowded, as it services “30 million, which is 4 million more than it was designed to handle.”[51] The current desire of the existing Jeju International Airport includes wanting to add more direct flights, nonstop to major cities including Tokyo, Osaka, Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei.[4]

While the economy booms with foreign travel, residents suffer negative repercussions of Jeju tourism. “Most commercial facilities are owned by foreigners and major companies.”[49] In addition to increasing tourism, issues such as beach pollution, traffic, and overconsumption of underground water present a problem.[49]

Jeju has three UNESCO World Heritage sites, and is “packed with museums and theme parks and also has horses, mountains, lava tube caves, and waterfalls with clear blue ocean lapping its beaches.”[4] The Haenyeo (Jeju female divers) harvest oysters, abalone, clams, seaweed and other marine life, and their history is showcased at the island's Haenyeo museum.[49]

Due to extensive tourism, the pollution of beaches has become a serious problem. The local government of Jeju aspires to be carbon-free by 2030.[49] “Nearly half of all-electric cars in South Korea are registered in Jeju”.[49]

In addition to the aspirations of an additional airport and the expansion of tourism on the island, Jeju is home to a small technological hub. In 2005, the Jeju Science Park was created, a complex for technology companies and organizations. Since its implementation, it has attracted 117 IT and biotech companies and is home to the Daum Kakao Corporation headquarters.[52]

One of the most popular surfing spots in Korea, Jeju Island is also the birthplace of Korean surfing. Some famous beaches are Weoljung Beach and Jungmun Beach. The latter is home to the first surfing club in Korea, established in 1995.[53]

There are small islands near Jeju Island that visitors can visit by boat; the most famous of these are Udo, Gapado, and Marado. Udo is famous for its peanut ice cream and boat tours.[54]

Jeju became more well known outside Korea after two characters in the 2021 Netflix original series Squid Game mentioned it.[55] It was also the location for two episodes of the 2022 Netflix original series Extraordinary Attorney Woo, entitled "The Blue Night of Jeju I and II".

Education

- North London Collegiate School Jeju is an independent British boarding school in Seogwipo for boys and girls from 4 to 19.

- Korean International School Jeju is an independent boarding school for boys and girls K–12.

- Branksome Hall Asia is an all-girls independent educational institution located in Seogwipo.

- St. Johnsbury Academy JeJu, a newly opened boarding and day school for boys and girls K–12 offering an American education based system, is located in Seogwipo.

- Jeju National University, a public university

- Jeju International University, a private university

- Cheju Halla University, a private college

- Jeju Tourism University, a private college

- Korea Polytechnics, a public post-secondary vocational school; the Jeju Campus is located in Jeju City.

Places of interest

- Love Land (South Korea), an outdoor sculpture park focused on a theme of sex

- Manjanggul Lava Tube, 8 km (5 mile) long with a 1 km (1000 yard) publicly accessible portion

- Seongsan Ilchulbong or "Sunrise Peak," a volcanic tuff cone and crater

- Mount Hallasan, the island's central dominant peak

- Mount Songaksan, a shore cliff and a low, flat grassland make a beautiful and easy walking trail

- Seongeup Folk Village

- Jeju Teddy's Bear Museum

- Figure Museum Jeju

- Jeju Maze Park

- Mysterious Road

- Water Falls (Jeongbang. Cheonjiyeon. Cheonjeyeon)

- O'Sulloc Tea Museum

- Beach (Jungmun. Hyeopjae)

- Ecoland Train Trip Theme Parks

- Natural Recreation Forest Jeolmul

- Jonjaamji, Korean Buddhist pagoda

Utilities

The island's power grid is connected to mainland plants by the HVDC Haenam–Cheju, and electricity is also provided by generators located on the island. As of 2001, there were four power plants on Jeju, with more under planning and construction. The most notable of these are the gas-fired generators of Jeju Thermal Power Plant, located in Jeju City. The present-day generators of this plant were constructed from 1982 onwards, replacing earlier structures that dated from 1968.[56] As elsewhere in Korea, the power supply is overseen by the Korea Electric Power Corporation, or KEPCO.

In February 2012, the governor of the state of Hawaii (USA), Neil Abercrombie, and the director of the Electricity Market and Smart Grid Division at the Korea Ministry of Knowledge Economy, Choi Kyu-Chong, signed a letter of intent to share information about Smart Grid technology. The Jeju Smart Grid was initially installed in 6,000 homes in Gujwa-eup and is being expanded. South Korea is using the pilot program of the Smart Grid on Jejudo as the testing ground in order to implement a nationwide Smart Grid by 2030.[57]

Transportation

The island is served by Jeju International Airport in Jeju City. The Seoul – Jeju City air route is by a significant margin the world's busiest, with around 13,400,000 passengers flown between the two cities in 2017.[58] Other cities that have flights to Jeju are Daegu, Busan, Gunsan and Gwangju.

Jeju is also accessible from Busan by ferry.[59] The travel time is between 3 and 12 hours.

The island has a public bus system, but there are no railways on the island.[60] A rail tunnel to the island, linking it to the Korea Train Express network has been proposed but is currently on hold due to cost concerns and local opposition in Jeju, who are aware of an eventual loss of their indigenous traits.[61]

Cheju/Jeju Naval Base

In 1993 the Republic of Korea (ROK) began planning a naval base on Jeju Island. Construction started in Gangjeong village in 2007, with planned completion by 2011.[62] The base was designed to be a mixed military-commercial port similar to those in Sydney and Hawaii, that could accommodate 20 warships and three submarines, as well as two civilian cruise ships displacing up to 150,000 tons. Its official name is the Jeju Civilian-Military Complex Port. Jeju residents, environmentalists, and opposition parties opposed the construction[63] claiming that environmental hazards will damage the "Island of Peace" designated as such by the government.[64] The protests caused delays in the construction. The base was completed in 2016.[65]

Health

In 2002, scarlet fever was reported to be in Korean children in Jeju Province.[66] Scientists have been doing research on the matter by creating an age-period-cohort (APC) analysis to back up their relevant hypotheses regarding this emerging outbreak. The Korean National Health Insurance Service analyzed this data from the nationwide insurance claims. Their calculations of the crude incidence rate (CIR) and applying the intrinsic estimator (IE) for age and calendar groups revealed that a total of 2,345 cases of children had the fever that was one of the top illnesses. It also led to the discovery that children aged 0–2 were the most common victims of the fever and that it was mostly boys rather than girls that carried it. The CIR decreased with age between 2002 and 2016 and the age period effect decreased in all observed years. The IE coefficients validating a cohort effect went from negative to positive in 2009. To this day, no one can explain how these children in Jeju Province had scarlet fever, but results suggest that it might be explained through the cohort effect. Further descriptive epidemiological studies are needed to test children that are born after 2009, to determine whether they have the fever or not.

Studies show that Jeju Province is recorded as the region showing the highest incidence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) in South Korea.[67] Just like the scarlet fever, the goal of this study was to determine the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of SFTS patients in Jeju Province. The data that was collected on this situation were obtained by the Integrated Diseases and Health Control System of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDCIS). 55 residents of Jeju were selected to test the criteria at KCDCIS and confirm the cases of SFTS with a residence listed in Jeju Province at the time of diagnosis, between July 16, 2014, and November 30, 2018. Results show that of the 55 confirmed cases of SFTS, the case fatality rate was 10.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.1 to 22.2). The most common symptoms of the SFTS were severe fever, myalgia, and diarrhea. There have been fatality rates of 83.6% (95% Cl, 71.2 to 92.2), 45.5% (95% Cl, 32.0 to 59.5), and 40.0% (95% CI, 27.0 to 54.1). This particular study from 2014 to 2018, has been proven to have a lower case fatality rate and a lower incidence of severe fever, myalgia, and confusion than that of the cases nationwide of 2013–2015.

See also

- Alddreu Airfield

- Jeju black cattle, indigenous cattle breed

- Jeju horse, indigenous horse breed

- Jeju language

- Jeju Volcanic Island and Lava Tubes

References

- "Joshua Calder's World Island Info - Largest Islands of Selected Countries". Worldislandinfo.com. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- Ministry of Public Administration and Security, September 30, 2020.

- Landsat/Copernicus; Data SIO; NOAA; United States Navy; NGA; GEBCO; TMap Mobility; TerraMetrics (2022). "Korea Strait" (Map). Google Earth. Alphabet. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- "Jeju Island". Business Traveller. February 2011.

- "Unesco names World Heritage sites". BBC News. June 28, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- Hulbert, H. B (1905). "The Island of Quelpart". Bulletin of the American Geographical Society. 37 (7): 396–408. doi:10.2307/198722. JSTOR 198722.

- "Photographic image of map". Archived from the original (JPG) on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- Hall, R. Burnett (1926). "Quelpart Island and Its People". Geographical Review. 16 (1): 60–72. doi:10.2307/208503. JSTOR 208503.

- Hulbert, Archer Butler (1902). "The Queen of Quelparte".

- Sokol, A. E (1948). "The Name of Quelpaert Island". Isis. 38 (3/4): 231–235. doi:10.1086/348077. S2CID 144230819.

- "Jeju Island Facts". Softschools.com.

- "The Island of Quelpart" (PDF). Fs.unm.edu.

- Sokol, A. E. (February 1948). "The Name Of Quelpaert Island". The University of Chicago Press. 38 (3/4): 231–235. doi:10.1086/348077. S2CID 144230819. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- "The memory and traces of marine exchange:Jeju Island in eastern and western antique maps" (PDF). eastsea1994.org. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- "제주특별자치도". 제주특별자치도청 (in Korean). Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- "The Queen of Tamna: Was Jeju previously ruled by a mythical warrior queen? - JEJU WEEKLY". Jejuweekly.com.

- Henthorn, William E. (1963). Korea: the Mongol invasions. E.J. Brill. pp. 190.

- Yang, Changyong; Yang, Sejung; O’Grady, William (2019-12-31). Jejueo: The Language of Korea's Jeju Island. University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. doi:10.2307/j.ctvwvr2qt.6. ISBN 978-0-8248-8140-5. JSTOR j.ctvwvr2qt. S2CID 241929091.

- Hugh Deane (1999). The Korean War, 1945-1953. China Books&Periodicals, Inc. pp. 54–58. ISBN 9780141912240.

- Merrill, John (1980). "Cheju-do Rebellion". The Journal of Korean Studies. 2: 139–197. doi:10.1353/jks.1980.0004. S2CID 143130387.

- Deane, Hugh (1999). The Korean War 1945-1953. San Francisco: China Books and Periodicals Inc. pp. 54–58. ISBN 978-0-8351-2644-1.

- Song Jung Hee, Islanders still mourn April 3 massacre, Jeju Weekly, March 3, 2010

- Murphy, Brian (22 June 2018). "How hundreds of Yemenis fleeing the world's worst humanitarian crisis ended up on a resort island in South Korea". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "South Koreans outraged as 500 Yemeni refugees flee to island". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Yemeni refugees' fate tested on Jeju Island". Korea Times. 17 June 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "South Korea to tighten laws amid influx of Yemeni asylum-seekers to resort island of Jeju". Straits Times. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- He-Rim, Jo (29 June 2018). "Justice Ministry proposes reinforcement measures to amend refugee act". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "제주 온 예멘인 500여 명 난민 신청..엇갈리는 시선". 다음 뉴스 (in Korean). 2018-06-19. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Jeju prepares for Kim Jong-un's visit by helicopter". koreatimes. November 11, 2018.

- "Summit bears fruit as South Korea flies tangerines to North - Channel NewsAsia". Channelnewsasia.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Ryall, Julian (November 8, 2018). "South Korea declares Kim Jong-un's mushrooms safe to eat". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Archaeologists discover 900-year-old lost treasure under the sea". All-sanfrancisco.com. 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- Map of Korea: Cheju Island Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine The People's Korea. Accessed 8 July 2012

- Woo, Kyung; Sohn, Young; Ahn, Ung; Spate, Andy (January 2013), "Geology of Jeju Island", Jeju Island Geopark - A Volcanic Wonder of Korea, Geoparks of the World (closed), 1: 13–14, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20564-4_5, ISBN 978-3-642-20563-7

- "RISS 통합검색 - 국내학술지논문 상세보기". Riss4u.net.

- "RISS 통합검색 - 학위논문 상세보기". Riss4u.net.

- Jang, Yong-chang and Chanwon Lee, 2009, "Gotjawal Forest as an internationally important wetland," Journal of Korean Wetlands Studies, 2009, Vol 1.

- "Ramsar site list" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2009. Retrieved 2007-06-20. Accessed June 2009

- "제주특별자치도 자연환경생태정보시스템". nature.jeju.go.kr. Archived from the original on 2016-07-12. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- Ap, Tiffany (January 25, 2016). "Deaths, travel disruption as bitter cold grips Asia". CNN. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- "Climatological Normals of Korea (1991 ~ 2020)" (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- 순위값 - 구역별조회 (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- "Climatological Normals of Korea" (PDF). Korea Meteorological Administration. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "제주도상세기후특성집(2010) 윗세오름(871)". Jeju Regional Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- Craig, Erin (October 2, 2018). "The unusual reason Chinese tourists are going to S Korea". BBC News.

- Lee, Yong-Sook (August 17, 2006). "The Korean War and tourism: Legacy of the war on the development of the tourism industry in South Korea". International Journal of Tourism Research. 8 (3): 157–170. doi:10.1002/jtr.569.

- Lee, B. J. On 12/12/08 at 7:00 (2008-12-12). "Sun and Seafood on Korea's Jeju Island". Newsweek. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- Jung, M.H (2018-01-04). "South Korea's Jeju Island suffers from 'too many tourists'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- Pile, Tim (June 2018). "The Hawaii of South Korea? The good, bad, ugly sides to Jeju Island". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- Einhorn, B., Kim, S., & Park, K. (March 13, 2017). "Beijing Is Mad About Thaad". Bloomsberg Businessweek.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jung, Min-ho (2018-01-04). "South Korea's Jeju Island suffers from 'too many tourists'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- W., E. (November 2014). "Too Reliant on Tourism? Jeju Tries Technology". Forbes Asia.

- Park, Jin Won (2018-08-03). "5 surfing spots to ride the wave in Korea". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- "우도(해양도립공원)". Visitjeju.net (in Korean). Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- "'Squid Game' draws attention to Jeju Island". Koreatimes. 2021-10-18. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- "Jeju Thermal P/P". Korea Midland Power website. Archived from the original on June 16, 2005. Retrieved July 29, 2005.

- "Korea and Hawaii join forces in Smart Grid venture". The Jeju Weekly. Feb 24, 2012. Retrieved Mar 5, 2012.

- Murray, Tom (2018-07-21). "The world's busiest air route is between Seoul and the 'South Korean Hawaii'". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- "VisitKorea - Ferry to Jeju". english.visitkorea.or.kr.

- "The all new Jeju public transportation system". Visitjeju.net. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "To Jeju, by train?". M.jejuweekly.com. 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- "Jeju naval base construction, Republic of Korea | EJAtlas". Environmental Justice Atlas.

- "Save Jeju Now". Savejejunow.org. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- "Cheju / Jeju Naval Base". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- "Jeju naval base". The Korea Herald. 2016-02-29. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- Kim, Jinhee; Kim, Ji-Eun; Bae, Jong-Myon (May 2019). "Incidence of Scarlet Fever in Children in Jeju Province, Korea, 2002-2016: An Age-period-cohort Analysis". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 52 (3): 188–194. doi:10.3961/jpmph.18.299. ISSN 1975-8375. PMC 6549015. PMID 31163954.

- Yoo, Jeong Rae; Heo, Sang Taek; Kim, Miyeon; Song, Sung Wook; Boo, Ji Whan; Lee, Keun Hwa (2019-12-01). "Seroprevalence of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome in the Agricultural Population of Jeju Island, Korea, 2015–2017". Infect Chemother. 51 (4): 337–344. doi:10.3947/ic.2019.51.4.337. ISSN 1598-8112. PMC 6940373. PMID 31668024.

External links

- Jeju Volcanic Island and Lava Tubes World Heritage site on Google Arts and Culture

Geographic data related to Jeju Island at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Jeju Island at OpenStreetMap