Jevons paradox

In economics, the Jevons paradox (/ˈdʒɛvənz/; sometimes Jevons effect) occurs when technological progress or government policy increases the efficiency with which a resource is used (reducing the amount necessary for any one use), but the falling cost of use increases its demand, negating reductions in resource use.[1] The Jevons' effect is perhaps the most widely known paradox in environmental economics.[2] However, governments and environmentalists generally assume that efficiency gains will lower resource consumption, ignoring the possibility of the effect arising.[3]

In 1865, the English economist William Stanley Jevons observed that technological improvements that increased the efficiency of coal use led to the increased consumption of coal in a wide range of industries. He argued that, contrary to common intuition, technological progress could not be relied upon to reduce fuel consumption.[4][5]

The issue has been re-examined by modern economists studying consumption rebound effects from improved energy efficiency. In addition to reducing the amount needed for a given use, improved efficiency also lowers the relative cost of using a resource, which increases the quantity demanded. This counteracts (to some extent) the reduction in use from improved efficiency. Additionally, improved efficiency increases real incomes and accelerates economic growth, further increasing the demand for resources. The Jevons' effect occurs when the effect from increased demand predominates, and the improved efficiency results in a faster rate of resource utilization.[5]

Considerable debate exists about the size of the rebound in energy efficiency and the relevance of the Jevons' effect to energy conservation. Some dismiss the effect, while others worry that it may be self-defeating to pursue sustainability by increasing energy efficiency.[3] Some environmental economists have proposed that efficiency gains be coupled with conservation policies that keep the cost of use the same (or higher) to avoid the Jevons' effect.[6] Conservation policies that increase cost of use (such as cap and trade or green taxes) can be used to control the rebound effect.[7]

History

The Jevons' effect was first described by the English economist William Stanley Jevons in his 1865 book The Coal Question. Jevons observed that England's consumption of coal soared after James Watt introduced the Watt steam engine, which greatly improved the efficiency of the coal-fired steam engine from Thomas Newcomen's earlier design. Watt's innovations made coal a more cost-effective power source, leading to the increased use of the steam engine in a wide range of industries. This in turn increased total coal consumption, even as the amount of coal required for any particular application fell. Jevons argued that improvements in fuel efficiency tend to increase (rather than decrease) fuel use, writing: "It is a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth."[4]

At that time, many in Britain worried that coal reserves were rapidly dwindling, but some experts opined that improving technology would reduce coal consumption. Jevons argued that this view was incorrect, as further increases in efficiency would tend to increase the use of coal. Hence, improving technology would tend to increase the rate at which England's coal deposits were being depleted, and could not be relied upon to solve the problem.[4][5]

The Jevons' effect is perhaps the most widely known pitfall in environmental economics.[2] Although Jevons originally focused on the issue of coal, the concept has since been extended to the use of any resource, including, for example, water usage[8] and interpersonal contact.[9] Although the concept of rebound effect was developed from the original theory by Jevons, the contemporary economics have traversed, to expand the scope of what is meant by rebound effects and to provide Jevons' effect a more concise definition. The concept of rebound effects has taken various iterations in different disciplines and has come to encompass several spheres of challenges and negative externalities.[10] Walnum et al. [11] carried out a systematic study of rebound effect research and observed the presence of seven viewpoints in which each provides unique interpretations and suppositions on the phenomenon: psychological study, ecological economics, energy economics, ecological economics, socio-technological discipline, evolutionary economics and urban planning. An eighth important position, that of industrial ecology, was also identified in further studies.[10] The expansion of slavery in the United States following the invention of the cotton gin has also been cited as an example of the effect.[12] The Jevons' effect is also found in socio-hydrology, in the safe development paradox called the reservoir effect, where construction of a reservoir to reduce the risk of water shortage can instead exacerbate that risk, as increased water availability leads to more development and hence more water consumption.[13][14]

Cause

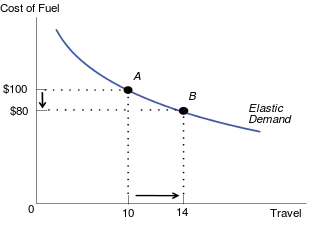

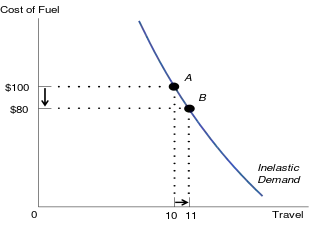

Economists have observed that consumers tend to travel more when their cars are more fuel efficient, causing a 'rebound' in the demand for fuel.[15] An increase in the efficiency with which a resource (e.g. fuel) is used causes a decrease in the cost of using that resource when measured in terms of what it can achieve (e.g. travel). Generally speaking, a decrease in the cost (or price) of a good or service will increase the quantity demanded (the law of demand). With a lower cost for travel, consumers will travel more, increasing the demand for fuel. This increase in demand is known as the rebound effect, and it may or may not be large enough to offset the original drop in fuel use from the increased efficiency. The Jevons' effect occurs when the rebound effect is greater than 100%, exceeding the original efficiency gains.[5]

The size of the direct rebound effect is dependent on the price elasticity of demand for the good.[16] In a perfectly competitive market where fuel is the sole input used, if the price of fuel remains constant but efficiency is doubled, the effective price of travel would be halved (twice as much travel can be purchased). If in response, the amount of travel purchased more than doubles (i.e. demand is price elastic), then fuel consumption would increase, and the Jevons' effect would occur. If demand is price inelastic, the amount of travel purchased would less than double, and fuel consumption would decrease. However, goods and services generally use more than one type of input (e.g. fuel, labour, machinery), and other factors besides input cost may also affect price. These factors tend to reduce the rebound effect, making the Jevons' effect less likely to occur.[5]

Khazzoom–Brookes postulate

In the 1980s, economists Daniel Khazzoom and Leonard Brookes revisited the Jevons' effect for the case of society's energy use. Brookes, then chief economist at the UK Atomic Energy Authority, argued that attempts to reduce energy consumption by increasing energy efficiency would simply raise demand for energy in the economy as a whole. Khazzoom focused on the narrower point that the potential for rebound was ignored in mandatory performance standards for domestic appliances being set by the California Energy Commission.[17][18]

In 1992, the economist Harry Saunders dubbed the hypothesis that improvements in energy efficiency work to increase (rather than decrease) energy consumption the Khazzoom–Brookes postulate, and argued that the hypothesis is broadly supported by neoclassical growth theory (the mainstream economic theory of capital accumulation, technological progress and long-run economic growth). Saunders showed that the Khazzoom–Brookes postulate occurs in the neoclassical growth model under a wide range of assumptions.[17][19]

According to Saunders, increased energy efficiency tends to increase energy consumption by two means. First, increased energy efficiency makes the use of energy relatively cheaper, thus encouraging increased use (the direct rebound effect). Second, increased energy efficiency increases real incomes and leads to increased economic growth, which pulls up energy use for the whole economy. At the microeconomic level (looking at an individual market), even with the rebound effect, improvements in energy efficiency usually result in reduced energy consumption.[20] That is, the rebound effect is usually less than 100%. However, at the macroeconomic level, more efficient (and hence comparatively cheaper) energy leads to faster economic growth, which increases energy use throughout the economy. Saunders argued that taking into account both microeconomic and macroeconomic effects, the technological progress that improves energy efficiency will tend to increase overall energy use.[17] Besides the neoclassical interpretation, hypotheses generated from heterodox economics also are consistent with the existence of the Jevons effect.[21]

Energy conservation policy

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

|

Jevons warned that fuel efficiency gains tend to increase fuel use. However, this does not imply that improved fuel efficiency is worthless if the Jevons' effect occurs; higher fuel efficiency enables greater production and a higher material quality of life.[22] For example, a more efficient steam engine allowed the cheaper transport of goods and people that contributed to the Industrial Revolution. Nonetheless, if the Khazzoom–Brookes postulate is correct, increased fuel efficiency, by itself, will not reduce the rate of depletion of fossil fuels.[17]

There is considerable debate about whether the Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate is correct, and of the relevance of the Jevons' effect to energy conservation policy. Most governments, environmentalists and NGOs pursue policies that improve efficiency, holding that these policies will lower resource consumption and reduce environmental problems. Others, including many environmental economists, doubt this 'efficiency strategy' towards sustainability, and worry that efficiency gains may in fact lead to higher production and consumption. They hold that for resource use to fall, efficiency gains should be coupled with other policies that limit resource use.[3][19][23] However, other environmental economists point out that, while the Jevons' effect may occur in some situations, the empirical evidence for its widespread applicability is limited.[24]

The Jevons' effect is sometimes used to argue that energy conservation efforts are futile, for example, that more efficient use of oil will lead to increased demand, and will not slow the arrival or the effects of peak oil. This argument is usually presented as a reason not to enact environmental policies or pursue fuel efficiency (e.g. if cars are more efficient, it will simply lead to more driving).[25][26] Several points have been raised against this argument. First, in the context of a mature market such as for oil in developed countries, the direct rebound effect is usually small, and so increased fuel efficiency usually reduces resource use, other conditions remaining constant.[15][20][27] Second, even if increased efficiency does not reduce the total amount of fuel used, there remain other benefits associated with improved efficiency. For example, increased fuel efficiency may mitigate the price increases, shortages and disruptions in the global economy associated with peak oil.[28] Third, environmental economists have pointed out that fuel use will unambiguously decrease if increased efficiency is coupled with an intervention (e.g. a fuel tax) that keeps the cost of fuel use the same or higher.[6]

The Jevons' effect indicates that increased efficiency by itself may not reduce fuel use, and that sustainable energy policy must rely on other types of government interventions as well.[7][21] As the imposition of conservation standards or other government interventions that increase cost-of-use do not display the Jevons' effect, they can be used to control the rebound effect.[7] To ensure that efficiency-enhancing technological improvements reduce fuel use, efficiency gains can be paired with government intervention that reduces demand (e.g. green taxes, cap and trade, or higher emissions standards). The ecological economists Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees have suggested that any cost savings from efficiency gains be "taxed away or otherwise removed from further economic circulation. Preferably they should be captured for reinvestment in natural capital rehabilitation."[6] By mitigating the economic effects of government interventions designed to promote ecologically sustainable activities, efficiency-improving technological progress may make the imposition of these interventions more palatable, and more likely to be implemented.[29]

Other examples

Food production

Reducing the price of food can increase consumption, regardless of whether the change applies to cheap or expensive (often calorie-dense) foods. This additional consumption can manifest as overeating. Making food cheaper is often suggested as a way to make people less poor. However, it can have the adverse effect of promoting obesity, which comes with an economic cost.

In the United States of America, in 2012, less than 10% of income was spent on food, compared to 14% in 1984. Obesity from 1984 onwards to 2014 increased for all demographic groups. From 1974 to 2012, sugary foods became more available than ever before, with food consumption outside of one's home becoming more and more common.[30][31]

Meat and dairy

Reducing the cost of production of meat, or dairy, may cause a problem, and increase overall consumption in countries where consumption is low at least so far and availability is relatively low as well. Increasing the efficiency of crop farming may increase pressure to deforest even more land for such production as well. Overall it would be an ecological loss.[32]

5G internet

Reducing prices per GB of 5G compared to 4G, they also have a lower cost in electricity per unit of data, but the rebound effect threatens to turn it against a reduction of consumption and instead create an increase of consumption.[33]

Population and economic development

Economic development may mitigate population growth rates, tending to lower reproductive rates by channeling women into the workplace, but it leads to an increase in energy use. More cars are used, more electricity is generated, and more greenhouse emissions are sent into the atmosphere.[34]

See also

- Downs–Thomson paradox, increasing road capacity can make traffic congestion worse

- Wirth's law, faster hardware can trigger the development of less-efficient software

- Andy and Bill's law, new software will always consume any increase in computing power that new hardware can provide

References

Notes

- Bauer, Diana; Papp, Kathryn (March 18, 2009). "Book Review Perspectives: The Jevons Paradox and the Myth of Resource Efficiency Improvements". Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy. 5 (1). doi:10.1080/15487733.2009.11908028.

- York, Richard (2006). "Ecological paradoxes: William Stanley Jevons and the paperless office" (PDF). Human Ecology Review. 13 (2): 143–147. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- Alcott, Blake (July 2005). "Jevons' paradox". Ecological Economics. 54 (1): 9–21. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.03.020. hdl:1942/22574.

- Jevons, William Stanley (1866). "VII". The Coal Question (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan and Company. OCLC 464772008. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- Alcott, Blake (2008). "Historical Overview of the Jevons paradox in the Literature". In JM Polimeni; K Mayumi; M Giampietro (eds.). The Jevons Paradox and the Myth of Resource Efficiency Improvements. Earthscan. pp. 7–78. ISBN 978-1-84407-462-4.

- Wackernagel, Mathis; Rees, William (1997). "Perceptual and structural barriers to investing in natural capital: Economics from an ecological footprint perspective". Ecological Economics. 20 (3): 3–24. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)00077-8.

- Freire-González, Jaume; Puig-Ventosa, Ignasi (2015). "Energy Efficiency Policies and the Jevons Paradox". International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy. 5 (1): 69–79. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Dumont, A.; Mayor, B.; López-Gunn, E. (2013). "Is the Rebound Effect or Jevons Paradox a Useful Concept for Better Management of Water Resources? Insights from the Irrigation Modernisation Process in Spain". Aquatic Procedia. 1: 64–76. doi:10.1016/j.aqpro.2013.07.006.

- Glaeser, Edward (2011), Triumph of the City: How Our Best Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, New York: Penguin Press, pp. 37–38, ISBN 978-1-59420-277-3

- Warmington-Lundström, Jon; Laurenti, Rafael (2020-01-01). "Reviewing circular economy rebound effects: The case of online peer-to-peer boat sharing". Resources, Conservation & Recycling: X. 5: 100028. doi:10.1016/j.rcrx.2019.100028. ISSN 2590-289X. S2CID 214076042.

- Walnum, Hans Jakob; Aall, Carlo; Løkke, Søren (December 2014). "Can Rebound Effects Explain Why Sustainable Mobility Has Not Been Achieved?". Sustainability. 6 (12): 9510–9537. doi:10.3390/su6129510. ISSN 2071-1050.

- "The paradox of the cotton gin and labor-saving technology — Transition Voice". transitionvoice.com. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- Naylor, David. "Press release - Uppsala University, Sweden". www.uu.se. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Di Baldassarre, Giuliano; Wanders, Niko; AghaKouchak, Amir; Kuil, Linda; Rangecroft, Sally; Veldkamp, Ted I. E.; Garcia, Margaret; van Oel, Pieter R.; Breinl, Korbinian; Van Loon, Anne F. (November 2018). "Water shortages worsened by reservoir effects". Nature Sustainability. 1 (11): 617–622. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0159-0. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 134508048.

- Small, Kenneth A.; Kurt Van Dender (2005-09-21). "The Effect of Improved Fuel Economy on Vehicle Miles Traveled: Estimating the Rebound Effect Using U.S. State Data, 1966–2001". Policy and Economics. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- Chan, Nathan W.; Gillingham, Kenneth (1 March 2015). "The Microeconomic Theory of the Rebound Effect and Its Welfare Implications". Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists. 2 (1): 133–159. doi:10.1086/680256. ISSN 2333-5955. S2CID 3681642.

- Saunders, Harry D. (October 1992). "The Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate and Neoclassical Growth". The Energy Journal. 13 (4): 131–148. doi:10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol13-No4-7. JSTOR 41322471.

- Herring, Horace (19 July 1999). "Does energy efficiency save energy? The debate and its consequences". Applied Energy. 63 (3): 209–226. doi:10.1016/S0306-2619(99)00030-6. ISSN 0306-2619.

- Sorrell, Steve (April 2009). "Jevons' Paradox revisited: The evidence for backfire from improved energy efficiency". Energy Policy. 37 (4): 1456–1469. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.12.003.

- Greening, Lorna; David L. Greene; Carmen Difiglio (2000). "Energy efficiency and consumption—the rebound effect—a survey". Energy Policy. 28 (6–7): 389–401. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00021-5.

- Amado, Nilton; Sauer, Ildo (February 2012). "An ecological economic interpretation of the Jevons effect". Ecological Complexity. 9: 2–9. doi:10.1016/j.ecocom.2011.10.003.

- Ryan, Lisa; Campbell, Nina (2012). "Spreading the net: the multiple benefits of energy efficiency improvements". IEA Energy Papers. doi:10.1787/20792581. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Owen, David (December 20, 2010). "Annals of Environmentalism: The Efficiency Dilemma". The New Yorker. pp. 78–.

- Gillingham, Kenneth; Kotchen, Matthew J.; Rapson, David S.; Wagner, Gernot (23 January 2013). "Energy policy: The rebound effect is overplayed". Nature. 493 (7433): 475–476. Bibcode:2013Natur.493..475G. doi:10.1038/493475a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23344343. S2CID 3220092.

- Potter, Andrew (2007-02-13). "Planet-friendly design? Bah, humbug". Maclean's. 120 (5): 14. Archived from the original on 2007-12-14. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- Strassel, Kimberley A. (2001-05-17). "Conservation Wastes Energy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2005-11-13. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Gottron, Frank (2001-07-30). "Energy Efficiency and the Rebound Effect: Does Increasing Efficiency Decrease Demand?" (PDF). National Council for Science and the Environment. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- Hirsch, R. L.; Bezdek, R.; and Wendling, R. (2006). "Peaking of World Oil Production and Its Mitigation". AIChE Journal. 52 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1002/aic.10747.

- Laitner, John A.; De Canio, Stephen J.; Peters, Irene (2003). Incorporating Behavioural, Social, and Organizational Phenomena in the Assessment of Climate Change Mitigation Options. Society, Behaviour, and Climate Change Mitigation. Advances in Global Change Research. Vol. 8. pp. 1–64. doi:10.1007/0-306-48160-X_1. ISBN 978-0-7923-6802-1.

- "Drones, crops and Jevons' Paradox". Centre for Society, Technology and Values. 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- foodnavigator.com. "The economics of obesity: How cheap processed food is fuelling the pandemic". foodnavigator.com. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- "Drones, crops and Jevons' Paradox". Centre for Society, Technology and Values. 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- "What is the impact of 5G on the environment? | Swisscom". www.swisscom.ch. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- Kunstler, James Howard (2005). The long emergency : surviving the converging catastrophes of the twenty-first century. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-87113-888-3.

Further reading

- Jenkins, Jesse; Nordhaus, Ted; Shellenberger, Michael (February 17, 2011). Energy Emergence: Rebound and Backfire as Emergent Phenomena (Report). Oakland, CA: The Breakthrough Institute. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology (5 July 2005). "3: The economics of energy efficiency". Select Committee on Science and Technology Second Report (Report). Session 2005–06. London, UK: House of Lords.

- Michaels, Robert J. (July 6, 2012). Energy Efficiency and Climate Policy: The Rebound Dilemma (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Institute for Energy Research. Retrieved 5 June 2015.