Jordan River (Utah)

The Jordan River, in the state of Utah, United States, is a river about 51 miles (82 km) long. Regulated by pumps at its headwaters at Utah Lake, it flows northward through the Salt Lake Valley and empties into the Great Salt Lake. Four of Utah's six largest cities border the river: Salt Lake City, West Valley City, West Jordan, and Sandy. More than a million people live in the Jordan Subbasin, part of the Jordan River watershed that lies within Salt Lake and Utah counties. During the Pleistocene, the area was part of Lake Bonneville.

| Jordan River Proveau's Fork, West Jordan River | |

|---|---|

Dam at Jordan River Narrows in 1901 | |

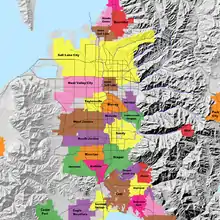

Map of the Jordan Subbasin and the location of Salt Lake County in Utah (inset) | |

| Etymology | Named after the Jordan River |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Utah |

| Counties | Utah, Salt Lake |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Utah Lake |

| • location | Utah County, Utah |

| • coordinates | 40°21′34″N 111°53′40″W[1] |

| • elevation | 4,489 ft (1,368 m)(compromise level)[2] |

| Mouth | Great Salt Lake |

• location | Davis County, Utah |

• coordinates | 40°53′52″N 111°58′25″W[1] |

• elevation | 4,200 ft (1,300 m)(historical average)[3] |

| Length | 51.4 mi (82.7 km)[4] |

| Basin size | 791 sq mi (2,050 km2)[5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | mouth |

| • average | 524 cu ft/s (14.8 m3/s) |

Members of the Desert Archaic Culture were the earliest known inhabitants of the region; an archaeological site found along the river dates back 3,000 years. Mormon pioneers led by Brigham Young were the first European American settlers, arriving in July 1847 and establishing farms and settlements along the river and its tributaries. The growing population, needing water for drinking, irrigation, and industrial use in an arid climate, dug ditches and canals, built dams, and installed pumps to create a highly regulated river.

Although the Jordan was originally a cold-water fishery with 13 native species, including Bonneville cutthroat trout, it has become a warm-water fishery where the common carp is most abundant. It was heavily polluted for many years by raw sewage, agricultural runoff, and mining wastes. In the 1960s, sewage treatment removed many pollutants. In the 21st century, pollution is further limited by the Clean Water Act, and, in some cases, the Superfund program. Once the home of bighorn sheep and beaver, the contemporary river is frequented by raccoons, red foxes, and domestic pets. It is an important avian resource, as does the Great Salt Lake and Utah Lake, visited by more than 200 bird species.

Big Cottonwood, Little Cottonwood, Red Butte, Mill, Parley's, and City creeks, as well as smaller streams like Willow Creek at Draper, Utah, flow through the subbasin. The Jordan River Parkway along the river includes natural areas, botanical gardens, golf courses, and a 40-mile (64 km) bicycle and pedestrian trail, completed in 2017.[6]

Course

The Jordan River is Utah Lake's only outflow. It originates at the northern end of the lake between the cities of Lehi and Saratoga Springs. It then meanders north through the north end of Utah Valley for approximately 8 miles (13 km) until it passes through a gorge in the Traverse Mountains, known as the Jordan Narrows. The Utah National Guard base at Camp Williams lies on the western side of the river through much of the Jordan Narrows.[7][8] The Turner Dam, located 41.8 miles (67.3 km) from the river's mouth (or at river mile 41.8) and within the boundaries of the Jordan Narrows, is the first of two dams of the Jordan River. Turner Dam diverts the water to the right or easterly into the East Jordan Canal and to the left or westerly toward the Utah and Salt Lake Canal. Two pumping stations situated next to Turner Dam divert water to the west into the Provo Reservoir Canal, Utah Lake Distribution Canal, and Jacob-Welby Canal. The Provo Reservoir Canal runs north through Salt Lake County, Jacob-Welby runs south through Utah County. The Utah Lake Distribution Canal runs both north and south, eventually leading back into Utah Lake.[9] Outside the narrows, the river reaches the second dam, known as Joint Dam, which is 39.9 miles (64.2 km) from the river's mouth. Joint Dam diverts water to the east for the Jordan and Salt Lake City Canal and to the west for the South Jordan Canal.[10][11][12]

The river then flows through the middle of the Salt Lake Valley, initially moving through the city of Bluffdale and then forming the border between the cities of Riverton and Draper.[7] The river then enters the city of South Jordan where it merges with Midas Creek from the west. Upon leaving South Jordan, the river forms the border between the cities of West Jordan on the west and Sandy and Midvale on the east. From the west, Bingham Creek enters West Jordan. Dry Creek, an eastern tributary, combines with the main river in Sandy. The river then forms the border between the cities of Taylorsville and West Valley City on the west and Murray and South Salt Lake on the east. The river flows underneath Interstate 215 in Murray. Little and Big Cottonwood Creeks enter from the east in Murray, 21.7 miles (34.9 km) and 20.6 miles (33.2 km) from the mouth respectively. Mill Creek enters on the east in South Salt Lake, 17.3 miles (27.8 km) from the mouth. The river runs through the middle of Salt Lake City, where the river travels underneath Interstate 80 a mile west of downtown Salt Lake City and again underneath Interstate 215 in the northern portion of Salt Lake City. Interstate 15 parallels the river's eastern flank throughout Salt Lake County. At 16 miles (26 km) from the mouth, the river enters the Surplus Canal channel. The Jordan River physically diverts from the Surplus Canal through four gates and heads north with the Surplus Canal heading northwest. Parley's, Emigration, and Red Butte Creeks converge from the east through an underground pipe, 14.2 miles (22.9 km) from the mouth.[7] City Creek also enters via an underground pipe, 11.5 miles (18.5 km) from the river's mouth. The length of the river and the elevation of its mouth varies year to year depending on the fluctuations of the Great Salt Lake caused by weather conditions. The lake has an average elevation of 4,200 feet (1,300 m) which can deviate by 10 feet (3.0 m).[3] The Jordan River then continues for 9 to 12 miles (14 to 19 km) with Salt Lake County on the west and North Salt Lake and Davis County on the east until it empties into the Great Salt Lake.[7][8][11]

Discharge

The United States Geological Survey maintains a stream gauge in Salt Lake City that shows annual runoff from the period 1980–2003 is just over 150,000 acre-feet (190,000,000 m3) per year or 100 percent of the total 800,000 acre-feet (990,000,000 m3) of water entering the Jordan River from all sources. The Surplus Canal carries almost 60 percent of the water into the Great Salt Lake, with various irrigation canals responsible for the rest. The amount of water entering the Jordan River from Utah Lake is just over 400,000 acre-feet (490,000,000 m3) per year. Inflow from the 11 largest streams feeding the Jordan River, sewage treatment plants, and groundwater each account for approximately 15 percent of water entering the river.[13]

Watershed

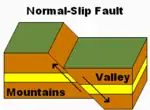

The Jordan Subbasin, as defined by the United States Geological Survey, is located entirely within Salt Lake and Utah counties in a roughly rectangular area of 791 square miles (2,050 km2). The Subbasin is part of the larger 3,830-square-mile (9,900 km2) Jordan River Basin that includes the upper Jordan River, Utah Lake, Provo and Spanish Fork Subbasins.[5][14] Four of the six largest cities in Utah are in Salt Lake County. The Jordan River flows through Sandy, with a 2010 population of 87,461; West Jordan, population 103,712; West Valley City, population 129,480; and Salt Lake City, population 186,440.[15] Flanked on either side by mountain ranges, the topography of the land varies greatly. The Wasatch Range rises on the east, with a high point of 11,100 feet (3,400 m) above sea level at Twin Peaks, near the town of Alta. The Oquirrh Mountains rise on the west, with a high point of over 9,000 feet (2,700 m) above sea level at Farnsworth Peak. The low point of 4,200 feet (1,300 m) is at the river's mouth, where the river enters the Great Salt Lake. Both the Oquirrh and Wasatch Mountains are fault-block mountains created from normal-slip faults where the mountains rise at the fault and the valley floor drops. The Wasatch Fault runs along the western edge of the Wasatch Mountains, and the Oquirrh Fault runs along the eastern edge of the Oquirrh Mountains.[16][17]

From approximately 75,000 to 8,000 years ago, much of what is now northern Utah was covered by a Pleistocene lake called Lake Bonneville. At its greatest extent, Lake Bonneville reached an elevation of 5,200 feet (1,600 m) above sea level and had a surface area of 19,800 square miles (51,000 km2). The lake left behind lacustrine sediments, which resulted in a relatively flat lake bed, and the valley floors have seen today. As the region experienced an increasingly warmer and drier climate over time, Lake Bonneville's water levels receded, leaving the Great Salt Lake and Utah Lake as remnants.[18] The river's greatest slope, 27 feet per mile (5.1 m/km), is in the Jordan Narrows, while the rest of the river has a more gentle slope of 2 to 4 feet per mile (0.4 to 0.8 m/km).[19]

Approximately 237,000 acres (960 km2) (46 percent of land area) of the Jordan Subbasin is in the Wasatch, Oquirrh and Traverse mountains.[20] The United States Forest Service manages 91,000 acres (370 km2) of land in the Wasatch Range. The vast majority of the Oquirrh Range is privately held,[21] with Kennecott Copper Mine owning most of the land. The State of Utah has scattered land holdings of 9,800 acres (40 km2) throughout the subbasin and owns the beds of all navigable streams and lakes.[20]

The Jordan Subbasin has two distinct climate zones. The lower elevations are characterized as a cold, semi-arid climate, with four distinct seasons. Both summer and winter are long, with hot, dry summers and cold, snowy winters. Salt Lake City receives 61 inches (150 cm) of snow annually, part of a total of 16.5 inches (420 mm) of precipitation per year. The mean maximum temperature is 91 °F (33 °C) in July and 37 °F (3 °C) in January[22] Areas of higher elevation have two distinct seasons, summer and winter. One of the areas of highest elevation, Alta, Utah, receives 458 inches (38.2 ft; 1,160 cm) of snow annually, part of a total of 46 inches (1,200 mm) of precipitation per year. The mean maximum temperature is 73 °F (23 °C) in July and 31 °F (−1 °C) in January.[23]

History

The first known inhabitants of the banks of the Jordan River were members of the Desert Archaic Culture, a group of nomadic hunter-gatherers. A 3,000-year-old archaeological site, called the Soo'nkahni Village, was uncovered next to the Jordan River.[24] The next recorded inhabitants, between 400 A.D. to around 1350 A.D., were the Fremont people, composed of several scattered bands of hunters and farmers living in what is now southern Idaho, western Nevada and most of Utah.[25] The disappearance of the Fremont people has been attributed to both changing climatic conditions, which put an end to favorable weather for farming, and to the arrival of ancestors to the present-day Ute, Paiute, and Northwestern Shoshone.[26] Although there were no permanent Native American settlements when European settlers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, the area bordered land occupied by several tribes, such as the Timpanogos band of the Utes in Utah Valley,[27] the Goshutes on the western side of the Oquirrh Mountain Range[28] and the Northwestern Shoshone north of the Salt Lake Valley.[29]

In 1776, Franciscan missionary Silvestre Vélez de Escalante was trying to find a land route from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Monterey, California. His party included twelve Spanish colonials and two Utes from the Utah Valley Timpanogots band who acted as guides. On 23 September 1776, the party entered Utah Valley at the present-day city of Spanish Fork. The local Timanogots villagers hosted them and told them of the lake to the north.[30] In his journal, Escalante described Utah Lake as a "lake, which must be six leagues wide and fifteen leagues long, [and] extends as far as one of these valleys. It runs northwest through a narrow passage, and according to what they told us, it communicates with others much larger." The Great Salt Lake was described as the "other lake with which this one communicates, according to what they told us, [and] covers many leagues, and its waters are noxious and extremely salty."[31]

The next group of Europeans to see the Jordan River was the party of Étienne Provost, a French Canadian trapper. In October 1824, Provost's party was lured into a Shoshone camp somewhere along the Jordan River, where they were attacked in retaliation for the murder of a local chief. In truth, the murder was committed by a member of Peter Skene Ogden's party. The men were caught off guard, and fifteen perished, but Provost and two others escaped.[32] The river was historically named Proveau's Fork,[33] as the Quebec-born fur trapper was known as Proveau and Provot, in addition to Provost (and the pronunciation was "Provo").[34]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 6,157 | — |

| 1900 | 77,725 | +1162.4% |

| 1950 | 274,895 | +253.7% |

| 1960 | 383,035 | +39.3% |

| 1970 | 458,607 | +19.7% |

| 1980 | 619,066 | +35.0% |

| 1990 | 725,956 | +17.3% |

| 2000 | 898,387 | +23.8% |

| 2010 | 1,029,655 | +14.6% |

| sources:[35][36][37] | ||

On 22 July 1847, the first party of Mormon pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, and five days later another party led by Brigham Young crossed the Jordan River and bathed in the Great Salt Lake.[38] The River Jordan (located in the Middle East) drains the Sea of Galilee into the Dead Sea in a way which the settlers found remarkably similar to the way the as-yet-unnamed local river drained Utah Lake into the saline Great Salt Lake. This similarity influenced the eventual name of the river, and on 22 August 1847, a conference was held and the name Western Jordan River was decided upon,[39] although it was later shortened to the Jordan River. By 1850, settlements were established along the Jordan River, Big Cottonwood Creek, Little Cottonwood Creek, Mill Creek, Parley's Creek and Emigration Creek.[40] In 1850, Captain Howard Stansbury of the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers traveled the entire length of the Jordan River,[41] surveying[42] and making observations of the wildlife.[43]

Around the year 1887 at Bingham Canyon in the Oquirrh Mountains, low-grade copper deposits were discovered and mining claims were filed. Bingham Canyon is a porphyry copper deposit where magma containing copper, molybdenum, gold and other minerals slowly moved its way to the surface and cooled into rock.[44] By 1890, underground copper mining had started, and in 1907, Kennecott Copper Mine started open pit mining.[45] In the early 20th century, mills were established near the Jordan River in Midvale and West Jordan to process ore. As of 2010, Kennecott Copper Mine's open pit is 2.8 miles (4.5 km) wide and 0.8 miles (1.3 km) deep.[46]

Throughout the 19th century and up to the 1940s, water from the Jordan River watershed sustained the agrarian society of the Salt Lake Valley. In 1950, Salt Lake County had 489,000 acres (764 sq mi; 1,980 km2) devoted to farming.[47] By 1992, however, the rapid urbanization of the Salt Lake Valley had reduced the amount of land devoted to farming to 108,000 acres (44,000 ha),[48] which was further reduced to 82,267 acres (33,292 ha) by 2002.[49]

River modifications

Alterations of the Jordan River watershed began two days after the Mormon Pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley when water was diverted from City Creek for irrigation.[50][51] The earliest dam and ditch along the Jordan River was constructed in 1849 to irrigate land on the west side of the river near present-day Taylorsville.[52] Other ditches include one built by Archibald Gardner, one of the founders of West Jordan in 1850, to provide water for his mill and one built by Alexander Beckstead, a founder of South Jordan, who built the Beckstead Ditch in 1859 to provide water for farmland. Many other small dams and ditches were also constructed in the first 25 years, several of which are still used as of 2010. All of these ditches irrigated only small amounts of land in the Jordan River floodplain; the largest, the Beckstead Ditch, irrigated 580 acres (230 ha).[53][54]

By the late 1860s, it became apparent that new, larger canals needed to be built if more acreage was to be farmed. The first dam in the Jordan Narrows was constructed in 1872 and raised in 1880, sparking an outcry from residents living near Utah Lake who thought the dam was responsible for raising the level of the lake. After several years of dispute, a commission was established to determine an acceptable compromise for the elevation of Utah Lake.[55] The commission's 1885 decision stated that if the lake level were to rise above the established compromise level, the Jordan River could not be impeded by either dams or flood gates. Additionally, the commission stated that after water pumps were installed at the source of the river, the pumps should all be working if the lake were to rise above the compromise level. However, if the lake level fell below the compromise level, pumps could be turned off so that water could be held for storage in Utah Lake.[56]

In 1875, the first large canal, the South Jordan Canal, was completed and it brought water to the area above the bluffs of the Jordan River for the first time.[57] All told, five large canals that originated from the dams in the Jordan Narrows were completed by 1883.[53] A second dam was built in 1890 a few miles (~5 km) downstream from the first dam and was constructed to better regulate the flow of two canals.[58] Both dams have been rebuilt in subsequent years and operate as diversion points for canals rather than impounding water by the use of sluice gates and head gates. The drought of 1901–1902 caused the Jordan River, on occasion, to stop flowing, and in response to the drought a pumping plant was installed at the outlet from Utah Lake. It was the largest pumping plant in the United States at the time, and contained seven pumps with a total capacity of 700 cubic feet (20 m3) per second.[59] Twice, during the droughts of 1934 and 1992, Utah Lake levels dropped so low that the pumps were rendered useless and the Jordan River actually ran dry.[60] In the 1950s, due to flood control measures to increase river velocity, large sections of the river were straightened in Salt Lake County. As part of the straightening process, meanders or curves in the river were cut off and the channel slope was increased. The river was also shifted to opposite sides of the flood plain in Midvale and Murray as part of local smelter operations.[61]

Floods in 1983–1984 caused Utah Lake to overflow its banks, flooding homes and farmland in Provo, Lehi and present-day Saratoga Springs. Dikes had to be constructed around Interstate 15 in Provo to prevent Utah Lake flooding the freeway. Big Cottonwood, Parley's, Emigration and City creeks flowed down sand-bag lined streets in order to manage the overflowing streams. Additional dikes were built at the Great Salt Lake to protect railroad lines and Interstate 80.[62][63] As a result of the flooding, the Utah Lake compromise level was amended to 4,489 feet (1,368 m).[2]

Ecology

Invertebrates and fish

In the Jordan River, invertebrates play an important role as a source of food for fish and other aquatic life, and they function as a parameter by which to measure water quality and the health of the river.[64] There are 34 different groups of invertebrates found in the Jordan River, most commonly of the class Oligochaeta (which includes earthworms), mosquito larvae and caddisfly larvae. The state of Utah maintains a Sensitive Species List that includes "those species for which there is credible scientific evidence to substantiate a threat to continued population viability."[65] The Lyrate mountainsnail[66] and the western pearlshell mussel,[67] both native to the Jordan River watershed, are found on this list.[68][69] A 2007 survey of invertebrates and their response to pollution stated that the Jordan River was substantially to severely impaired with organic pollution and that it contained reduced levels of dissolved oxygen.[70]

Historically, the Jordan River was a cold-water fishery that contained 13 native species, including the Bonneville cutthroat trout, Utah Lake sculpin, June sucker, Mottled sculpin, Utah chub and the Utah sucker. Today, the Jordan River is a warm-water fishery with the Utah sucker and the endangered June sucker present only in Utah Lake. The Utah chub, however, is still found in the Jordan River.[71] The most common species of fish encountered today is the common carp, which was introduced into the Jordan River and Utah Lake as a source of food after overfishing caused the depletion of native species stocks.[72][73] The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources regularly stocks the river with catfish and rainbow trout.[74]

Wildlife

Before the area was urbanized, mammals such as bighorn sheep, mule deer, coyote, wolves, beaver, muskrat and jackrabbits would have been seen along the river. A "varmint hunt" was organized by John D. Lee around 1848, after the arrival of Mormon settlers. The final count of the hunt included "two bears, two wolverines, two wildcats, 783 wolves, 409 foxes, 31 minks, nine eagles, 530 magpies, hawks and owls, and 1,026 ravens."[75] None of the original large mammals is found along the Jordan River today; they have, for the most part, been replaced by raccoons, red foxes and domestic pets.[76] Animals from the Jordan River area found on the Utah Sensitive Species List include the smooth green snake,[77] the western toad,[78] kit fox,[79] spotted bat,[80] and Townsend's big-eared bat.[81][82]

Combined with Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake, the Jordan River offers one of the region's richest bird resources. Over 200 bird species use the river for breeding habitat or as a stop-over on their migratory routes.[83] Once-common native species such as the willow flycatcher, gray catbird, warbling vireo, American redstart, black tern, and yellow-billed cuckoo are no longer found along the river. The common yellowthroat and yellow-breasted chat are still found in small isolated populations. The most common species now found are the black-billed magpie, mourning dove, western meadowlark, barn swallow, and the non-native ring-necked pheasant and starlings.[84]

Vegetation

Vegetation in the watershed is closely tied to elevation and precipitation levels. About 30 percent of the basin, mostly at higher elevation levels, is populated with oak, aspen and coniferous trees. At the lower levels, 27 percent of the basin is rich in mountain-brush, sagebrush, juniper and grasses. About 34 percent of the Jordan River basin is classified as urban.[85]

Russian olive and tamarisk or salt cedar trees now dominate the Jordan River floodplain where willow trees and cottonwood trees would once have been found. Plant species such as foxtail barley, saltgrass, rabbitbrush, cattails and other reeds are still found in small pockets along the river.[86] Exotic pasture grasses such as orchard grass, bluegrass, redtop bentgrass, quackgrass, wheatgrass and fescue have become the common species of grass.[87] The vulnerable flower, Ute's Ladies'-tresses, can also be found along the river.[88]

Pollution

The Jordan River has been a repository for waste since the settling of the Salt Lake Valley. For 100 years, raw, untreated sewage was dumped into the river; farming and animal runoff occurred; and mining operations led to 40 smelters being built and contaminating the river with heavy metals, mostly arsenic and lead. In 1962, the river in Midvale recorded a total coliform level of about 3 million per 100 milliliters,[89] even though the state of Utah criteria for the total number of coliform bacteria in water samples should not exceed 5,000 per 100 milliliters. In 1965, a new sewage treatment plant came on-line in Salt Lake City that prevented 32,000,000 US gallons per day (120,000 m3/d) of raw sewage from being dumped into a canal.[90]

The Utah Division of Water Quality and Utah Division of Drinking Water are responsible for the regulation and management of water quality in the State of Utah. Streams that exceed the standard contamination levels are placed on the 303d list in accordance with the Clean Water Act. The Act also requires states to identify impaired water bodies every two years and develop a total maximum daily load (TMDL) for pollutants that may cause impairments in the various water bodies.[91] The Jordan River and Little Cottonwood Creek were included on the 2006 303d list; parameters that exceeded the standard level for at least part of the Jordan River include temperature, dissolved oxygen, total dissolved solids, E. Coli and salinity.[92]

EPA Superfund sites

Superfund sites are designated as being among the nation's worst areas with respect to toxic and hazardous waste. The Environmental Protection Agency is the federal agency that determines if a particular site is hazardous, prepares a course of action to reduce the hazard, and finds the parties responsible for the pollution. If a site is listed with the Superfund program, federal dollars are available for cleanup.[93]

The Kennecott South Zone/Bingham site contains contamination from Kennecott Copper Mine's operation in Copperton, at the base of the Oquirrh Mountains to Bingham Creek and Butterfield Creek. A 72-square-mile (190 km2) plume of lead, arsenic and sulfates (covering 9 percent of the watershed) currently contaminates the ground water from the mine site all the way to the Jordan River. The largest inland reverse osmosis plant in the country was built in 2006 to clean up the ground water and a second plant has been scheduled for construction; completion of the ground water cleanup, however, is not projected until 2040. In 1998, the site was removed from the Superfund list due to Kennecott's progress in the cleanup and a consent decree legally obligating Kennecott to continue the rest of the cleanup.[94][95]

_in_Midvale.JPG.webp)

The Murray Smelter site was the location of a large lead smelter in operation from 1872 until 1949. The 142-acre (57 ha) site contained groundwater contamination from arsenic and lead, but the majority of the cleanup was completed in 2001.[96]

In Midvale, there are two Superfund sites that sit along 4 percent of the Jordan River. The Midvale Slag site is a 446-acre (180 ha) site adjacent to 6,800 feet (2,100 m) of the Jordan River. From 1871 to 1958, the site contained five separate smelters that processed ores from Kennecott and other mines. The site was contaminated with lead, arsenic, chromium, and cadmium. Cleanup of the property is complete, although the Jordan River Riparian Project still underway as of 2010.[97][98] Sharon Steel was a 460-acre (190 ha) site adjacent to 4,500 feet (1,400 m) of the Jordan River which was used, from 1902 to 1971, for smelting copper from Kennecott Copper Mine. The site was contaminated with lead, arsenic, iron, manganese, and zinc. Cleanup has been completed, and the site taken off the Superfund list in 2004.[99]

Uranium mill tailings

Vitro Uranium Mill was a 128-acre (52 ha) site located in South Salt Lake, surrounded by the Jordan River, Mill Creek, a small wetland and traversed by the South Vitro Ditch. The site, operational from 1953 to 1964, contained a uranium mill and storage for uranium. In 1989, surface contamination cleanup was completed with tailings, radioactively contaminated soil material, and debris removed from the site.[100] However, 700,000,000 US gallons (2,600,000 m3) of contaminated shallow ground water still remain, and studies are underway to determine what action should be taken.[101]

Jordan River Parkway

The Jordan River Parkway was originally proposed in 1971 as a flood control measure with two reservoirs, restoration of wetlands, shoreline roads for cars, walking trails, and parks.[102][103] By 1986, $18 million had been used to purchase lands around the Jordan River and to construct the Murray Golf Course, several smaller parks and about 4 miles (6.4 km) of canoe runs and trails.[104] As of 2010, the majority of the 40-mile (64 km) continuous mixed-use trail has been finished from Utah Lake to the Davis County border.[105] A water trail for canoeing and kayaking is also being constructed, but dams, bridges, weirs and other obstacles hamper the use of the river.[106]

Riverside parks include the International Peace Gardens, 8.5 acres (3.4 ha) of gardens with each garden representing a different country;[107] Redwood Nature Area, about 50 acres (20 ha) of natural areas;[108] South Jordan's Riverfront Park, 59 acres (24 ha) of trails, fishing ponds and natural areas;[109] Thanksgiving Point, including 15 themed gardens spread over 59 acres,[110] and a 200-acre (81 ha), 18-hole golf course;[111] and Utah County's Willow Park, 50 acres (20 ha) of camping and wildlife areas.[112]

See also

- List of Utah rivers

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Jordan River

- Utah Lake and Jordan River Water Rights and Management Plan 1989, p. 4

- "Great Salt Lake, Utah", Utah Water Science Center, United States Geological Survey, archived from the original on 6 May 2010, retrieved 25 Mar 2010

- Length per Utah Division of Water Quality Jordan River TMDL 2009, p. 18 (some sources quote other lengths)

- Hydrologic Survey Maps 1987, p. 53

- Completion of the Jordan River Parkway, Jordan River Commission

- "USGS Scanned Topographic Maps (1:100000, GeoTIFF)". Utah GIS Portal. Archived from the original on 2010-04-24. Retrieved 21 Apr 2010.

- "Municipalities", Utah SGID: Vector GIS Data Layer Download Index, Utah GIS Portal, archived from the original on 2010-04-22, retrieved 21 Apr 2010

- Hydrology of Northern Utah Valley 2005, pp. 4–31

- Mead 1904, pp. 55–56

- Jordan River TMDL 2009, p. 19

- Utah Lake and Jordan River Water Rights and Management Plan 1989, pp. 1–2

- Jordan River TMDL 2009, pp. 35–39

- Recommended Watershed Terminology, Watershed Management Council, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 25 May 2010

- "Population and Housing Occupancy Status: 2010 – State – Place". United States Census Bureau. 2010. Retrieved 7 Jan 2012.

- Black et al. 1996, pp. 1–3

- Lund 1996, pp. 1–3

- Brimhall & Merritt 1981, pp. 25–27

- Jordan River Stability Study 1992, pp. 3–5

- "Watershed Facts". Watershed Planning and Restoration Program. Salt Lake County, Utah. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 Mar 2010.

- Oquirrh Mountains 1999, p. 2

- Salt Lake City Climatology 2004, pp. 1–3

- Alta Climatology 2020

- "Tribal leaders say UTA 'ignores' them". Salt Lake Tribune. 4 Mar 2010.

- Madsen, David B. (1994), "The Fremont", in Powell, Allan Kent (ed.), Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0-87480-425-6, OCLC 30473917, archived from the original on 2013-11-01, retrieved 2013-10-31

- Madsen 2002, pp. 13–14

- Janetski 1991, pp. 32–33

- Cuch 2000, p. 75

- Madsen 1985, pp. 6–7

- Alexander, Thomas G. "Dominguez-Escalante Expedition". Utah History to Go. Utah State Historical Society. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- "Derrotero y Diario", Early Americas digital archive, Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, archived from the original on 2011-09-28, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- Alter, Cecil (1941), "Journal of W.A. Ferris 1830–1835", Utah Historical Quarterly, 9: 105–106

- John W. Van Cott (1990). Utah Place Names: A Comprehensive Guide to the Origins of Geographic Names: A Compilation. University of Utah Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780874803457. Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- LeRoy R. Hafen (1965). Trappers of the Far West: Sixteen Biographical Sketches. University of Nebraska Press. p. 1. ISBN 0803272189. Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- Fisher 1855, p. 870

- Utah Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990, U.S. Census, archived from the original on 3 April 2015, retrieved 21 Apr 2010

- "Salt Lake County, Utah", State & County QuickFacts, U.S. Census, archived from the original on 2011-07-14, retrieved 15 Jan 2013

- Bancroft 1889, p. 263

- Bancroft 1889, p. 266

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, p. 24

- Stansbury 1852, pp. 156–157

- Stansbury 1852, p. 297

- Stansbury 1852, pp. 307–397

- Tooker, Edwin (1990), "Gold in the Bingham district, Utah", US Geological Survey Bulletin, 1857-E

- Cononelos, Louis J.; Notarianni, Philip F. (1994), "Kennecott Corporation", in Powell, Allan Kent (ed.), Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0-87480-425-6, OCLC 30473917, archived from the original on 2013-11-01, retrieved 2013-10-31

- "Facts about our mine". Kennecott Utah Copper. Archived from the original on 2010-04-10. Retrieved 21 Apr 2010.

- 1950 Census of Agriculture 1950, p. 3

- 1992 Census of Agriculture 1992, p. 3

- 2002 Census of Agriculture 2002, p. 3

- Alexander, Thomas G. (Spring 2002), "Irrigating the Mormon Heartland: The Operation of the Irrigation Companies in Wasatch Oasis Communities, 1847–1880", Agricultural History, 6 (2): 172–197, doi:10.1525/ah.2002.76.2.172

- Bancroft 1889, p. 261

- Mead 1904, p. 55

- Mead 1904, p. 60

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, p. 6

- Mead 1904, pp. 63–64

- Utah Lake and Jordan River Water Rights and Management Plan 1989, pp. 2–3

- Mead 1904, p. 42

- Mead 1904, pp. 64–65

- Utah Lake and Jordan River Water Rights and Management Plan 1989, pp. 8–9

- Utah Lake and Jordan River Water Rights and Management Plan 1989, p. 28

- Jordan River Stability Study 1992, section 3, pp. 9–12

- Sillitoe, Linda. "Floods". Utah History to Go. Utah State Historical Society. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 21 Apr 2010.

- Davidson, Leo (May 27, 1983). "Floods cause extensive damage as sun melts heavy snowpack". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 21 Apr 2010.

- Jordan River TMDL 2007, p. 91

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, p. 1

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, pp. 81–82

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, pp. 100–102

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, p. 185

- Fishery and Macroinvertebrate Studies 1986, p. 32

- Jordan River TMDL 2007, pp. 93–94

- "Utah Lake: Native Fish Community". June Sucker Recovery Implementation Program. Archived from the original on 2010-12-10. Retrieved 29 Mar 2010.

- "Isciculture in Utah". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. 9 Nov 1889. Retrieved 29 Mar 2010.

- Carp In Utah Lake Impacting Ecosystem 2004, p. 1

- Jordan River TMDL 2007, pp. 96–98

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report 2000, section 2, p. 11

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report 2000, section 2, p. 12

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, pp. 30–31

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, p. 14

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, pp. 76–77

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, pp. 57–58

- Utah Sensitive Species List 2007, pp. 58–59

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, pp. 184–185

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report 2000, section 2, p. 13

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report 2000, section 2, p. 14

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, pp. 6–7

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report 2000, section 2, p. 18

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report 2000, section 2, p.20

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, p. 184

- "Pollution Unit Calls For River Action". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. 16 Nov 1972. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- "Conduits of Civilization". Salt Lake City. Archived from the original on 2011-05-03. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- "Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL)". Utah Division of Water Quality. Archived from the original on 2010-06-30. Retrieved 1 Apr 2010.

- Utah's 2006 Integrated Report 2006, pp. II–26 to II–27

- "Superfund and Other Sources of Land Contamination – National Overview". Green Media Toolshed. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 26 Apr 2010.

- "Kennecott South Zone/Bingham Superfund Program". Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- Johnson, Francis (16 Feb 2009). "Kennecott invests $400 million in removing Utah land from proposed inclusion on EPA's Superfund list" (PDF). The Enterprise. Salt Lake City. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- Murray Smelter Superfund Program, Environmental Protection Agency, archived from the original on 2009-06-13, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- "Midvale Slag Superfund Program". Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- Riparian Improvement Project Fact Sheet 2008, pp. 1–3

- Sharon Steel Superfund Program, Environmental Protection Agency, archived from the original on 2010-11-11, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- "Salt Lake City Mill Site". United States Department of Energy, U.S. Energy Information Administration. Oct 2005. Archived from the original on 2010-04-05. Retrieved 27 Mar 2010.

- Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future 2010, p. 167

- Jordan River Parkway, An Alternative 1971, p. 15

- Jordan River Parkway, An Alternative 1971, pp. 94–108

- "Jordan Parkway: Two rivers in search of a new identity". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. 22 Jan 1986. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 2 Apr 2010.

- "Jordan River Parkway Trail". Salt Lake City. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 1 Apr 2010.

- Jordan River Trail Master Plan 2008, section 4, pp. 1–34

- "International Peace Gardens". International Peace Gardens. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 20 Apr 2010.

- "Redwood Nature Area". Salt Lake County, Utah. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 20 Apr 2010.

- "Riverfront Park". South Jordan City. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 20 Apr 2010.

- "Gardens". Thanksgiving Point. Archived from the original on 2010-04-07. Retrieved 20 Apr 2010.

- "Golf". Thanksgiving Point. Archived from the original on 2010-04-29. Retrieved 20 Apr 2010.

- "Willow Park". Utah County. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 28 Mar 2010.

Bibliography

Books

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1889), History of Utah: 1540–1886, San Francisco: The History Company, ISBN 978-1-153-38612-8, archived from the original on 21 October 2013, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- Black, Bill D.; Lund, William R.; Schwartz, David P.; Gill, Harold E.; Mayes, Bea M. (1996), Paleoseismic investigation on the Salt Lake City segment of the Wasatch zone at South Fork Dry Creek and Dry Gulch Sites, Salt Lake County, Utah, Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey, ISBN 978-1-55791-399-9, archived from the original on 19 October 2021, retrieved 25 May 2010

- Cuch, Forrest S., ed. (2000), A History of Utah's American Indians, Logan: Utah State University Press, ISBN 978-0-913738-48-1, archived from the original on 21 June 2011, retrieved 20 Mar 2010

- Fisher, Richard S. (1855), A new and complete statistical gazetteer of the United States of America, New York City: J.H. Colton and Company, archived from the original on 15 January 2018, retrieved 21 Apr 2010

- Janetski, Joel C. (1991), The Ute of Utah Lake, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, ISBN 978-0-87480-343-3

- Lund, William R. (1996), The Oquirrh fault zone, Tooele County, Utah: surficial geology and paleoseismicity, Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey, ISBN 978-1-55791-370-8, archived from the original on 19 October 2021, retrieved 25 May 2010

- Madsen, Brigham D. (1985), The Shoshoni Frontier and the Bear River Massacre, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, ISBN 978-0-87480-494-2

- Madsen, David B. (2002), Exploring the Fremont, Salt Lake City: Utah Museum of Natural History, ISBN 978-0-940378-35-3

- Mead, Elwood (1904), Report of irrigation investigations in Utah, Washington D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture, Office of Experiment Stations, ISBN 978-1-142-17418-7, archived from the original on 19 October 2021, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- Stansbury, Howard (1852), Exploration and Survey of the valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah, United States Senate, ISBN 978-0-548-21928-7, archived from the original on 20 September 2014, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

Reports

- "Alta, UT", U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 1991–2020, retrieved 4 Apr 2022

- "County Summary Highlights: 1992" (PDF), 1992 Census of Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, 1992, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-07, retrieved 29 Mar 2010

- "County Summary Highlights: 2002" (PDF), 2002 Census of Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, 2002, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-06, retrieved 21 Apr 2010

- Carp In Utah Lake Impacting Ecosystem (PDF), June Sucker Recovery Implementation Program, June 2004, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19, retrieved 29 Mar 2010

- Fishery and Macroinvertebrate Studies of the Jordan River in Salt Lake County, Central Valley Water Reclamation Facility Board, November 1986

- Brimhall, Willis H.; Merritt, Lavere B. (1981), "Geology of Utah Lake: Implications for Resource Management", Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs (5: Utah Lake Monograph): 25–27, archived from the original on 8 October 2011, retrieved 19 Apr 2010

- Seaber, Paul R.; Kapinos, Paul; Knapp, George L. (1987), "Hydrologic Unit Maps" (PDF), U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2294, United States Government Printing Office, archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2011, retrieved 25 May 2010

- Hydrology of Northern Utah Valley, Utah County, Utah, 1975–2005 (PDF), U.S. Geological Survey, February 2009, archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-14, retrieved 2010-06-17

- "Jordan River Basin Planning for the Future" (PDF), Utah State Water Plan, Utah Division of Water Resources, March 2010, archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2010, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- Jordan River Natural Conservation Corridor Report (PDF), Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission & US Fish and Wildlife Service, September 2000, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-25, retrieved 29 Mar 2010

- Jordan River Parkway, An Alternative (PDF), Urban Technology Associates, 1971, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010, retrieved 2 Apr 2010

- "Jordan River Stability Study" (PDF), Watershed Planning and Restoration Program, Salt Lake County, Utah, December 1992, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010, retrieved 25 Mar 2010

- Jordan River TMDL: Work Element 1 – Evaluation of Existing Information (PDF), Utah State Division of Water Quality, March 2007, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27, retrieved 22 Apr 2010

- Jordan River TMDL: Work Element 2 – Pollutant Identification and Loading (PDF), Utah State Division of Water Quality, July 2009, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27, retrieved 22 Apr 2010

- Jordan River Trail Master Plan (PDF), Salt Lake County Parks and Recreation, 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010, retrieved 6 Apr 2010

- "Oquirrh Mountains" (PDF), Utah Wilderness Survey, Bureau of Land Management, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-10, retrieved 26 Mar 2010

- "Riparian Improvement Project Fact Sheet" (PDF), Midvale Slag Superfund Program, Environmental Protection Agency, October 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-01, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- "Salt Lake City Climatology" (PDF), Climatography of the United States, National Climatic Data Center, February 2004, retrieved 16 Jun 2010

- "Statistics for Counties" (PDF), 1950 Census of Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, 1950, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-04, retrieved 29 Mar 2010

- Utah Lake and Jordan River water rights and management plan (PDF), Salt Lake City, 1989, retrieved 28 Mar 2010

- Utah's 2006 Integrated Report Volume II – 303(d) List of Impaired Waters (PDF), Department of Environmental Quality Division of Water Quality, 2006, retrieved 27 Mar 2010

- Utah Sensitive Species List (PDF), Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, December 2007, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2010, retrieved 23 Apr 2010

External links

- Historical and forecasted outflow from Utah Lake via the Jordan River

- Historical and forecasted stream flow of the Jordan River in northern Salt Lake City

- Historical and forecasted stream flow of the Jordan River in Sandy

- Historical and forecasted stream flow of the Jordan River Surplus Canal

- Jordan River Trail Master Plan

- Jordan River Watershed Planning and Restoration Program

- United States Geological Survey's Water Resources Links for the Jordan Subbasin