Keloid

Keloid, also known as keloid disorder and keloidal scar,[1] is the formation of a type of scar which, depending on its maturity, is composed mainly of either type III (early) or type I (late) collagen. It is a result of an overgrowth of granulation tissue (collagen type 3) at the site of a healed skin injury which is then slowly replaced by collagen type 1. Keloids are firm, rubbery lesions or shiny, fibrous nodules, and can vary from pink to the color of the person's skin or red to dark brown in color. A keloid scar is benign and not contagious, but sometimes accompanied by severe itchiness, pain,[2] and changes in texture. In severe cases, it can affect movement of skin. Worldwide, men and women of African, Asian, Hispanic and European descent can develop these raised scars. In the United States keloid scars are seen 15 times more frequently in people of sub-Saharan African descent than in people of European descent. There is a higher tendency to develop a keloid among those with a family history of keloids and people between the ages of 10 and 30 years.

| Keloid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bulky keloid forming at the site of abdominal surgery | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Usual onset | scar formation |

Keloids should not be confused with hypertrophic scars, which are raised scars that do not grow beyond the boundaries of the original wound.

Signs and symptoms

Keloids expand in claw-like growths over normal skin.[3] They have the capability to hurt with a needle-like pain or to itch, the degree of sensation varying from person to person.

Keloids form within scar tissue. Collagen, used in wound repair, tends to overgrow in this area, sometimes producing a lump many times larger than that of the original scar. They can also range in color from pink to red.[4] Although they usually occur at the site of an injury, keloids can also arise spontaneously. They can occur at the site of a piercing and even from something as simple as a pimple or scratch. They can occur as a result of severe acne or chickenpox scarring, infection at a wound site, repeated trauma to an area, excessive skin tension during wound closure or a foreign body in a wound. Keloids can sometimes be sensitive to chlorine. If a keloid appears when someone is still growing, the keloid can continue to grow as well.

Images |

|---|

|

Location

Keloids can develop in any place where skin trauma has occurred. They can be the result of pimples, insect bites, scratching, burns, or other skin injury. Keloid scars can develop after surgery. They are more common in some sites, such as the central chest (from a sternotomy), the back and shoulders (usually resulting from acne), and the ear lobes (from ear piercings). They can also occur on body piercings. The most common spots are earlobes, arms, pelvic region, and over the collar bone.

Cause

Most skin injury types can contribute to scarring. This includes burns, acne scars, chickenpox scars, ear piercing, scratches, surgical incisions, and vaccination sites.

According to the (US) National Center for Biotechnology Information, keloid scarring is common in young people between the ages of 10 and 20. Studies have shown that those with darker complexions are at a higher risk of keloid scarring as a result of skin trauma. They occur in 15–20% of individuals with sub-Saharan African, Asian or Latino ancestry, significantly less in those of a Caucasian background. Although it was previously believed that people with albinism did not get keloids,[5] a recent report described the incidence of keloids in Africans with albinism.[6] Keloids tend to have a genetic component, which means one is more likely to have keloids if one or both of their parents has them. However, no single gene has yet been identified which is a causing factor in keloid scarring but several susceptibility loci have been discovered, most notably in Chromosome 15.[5][7]

Genetics

_(14595050100).jpg.webp)

People who have ancestry from Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, or Latin America are more likely to develop a keloid. Among ethnic Chinese in Asia, the keloid is the most common skin condition. In the United States, keloids are more common in African Americans and Hispanic Americans than European Americans. Those who have a family history of keloids are also susceptible since about 1/3 of people who get keloids have a first-degree blood relative (mother, father, sister, brother, or child) who also gets keloids. This family trait is most common in people of African and/or Asian descent.

Development of keloids among twins also lends credibility to existence of a genetic susceptibility to develop keloids. Marneros et al. (1) reported four sets of identical twins with keloids; Ramakrishnan et al.[8] also described a pair of twins who developed keloids at the same time after vaccination. Case series have reported clinically severe forms of keloids in individuals with a positive family history and black African ethnic origin.

Pathology

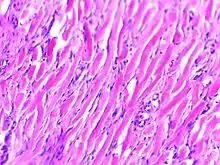

Histologically, keloids are fibrotic tumors characterized by a collection of atypical fibroblasts with excessive deposition of extracellular matrix components, especially collagen, fibronectin, elastin, and proteoglycans. Generally, they contain relatively acellular centers and thick, abundant collagen bundles that form nodules in the deep dermal portion of the lesion. Keloids present a therapeutic challenge that must be addressed, as these lesions can cause significant pain, pruritus (itching), and physical disfigurement. They may not improve in appearance over time and can limit mobility if located over a joint.

Keloids affect both sexes equally, although the incidence in young female patients has been reported to be higher than in young males, probably reflecting the greater frequency of earlobe piercing among women. The frequency of occurrence is 15 times higher in highly pigmented people. People of African descent have increased risk of keloid occurrences.[9]

Treatments

Prevention of keloid scars in patients with a known predisposition to them includes preventing unnecessary trauma or surgery (such as ear piercing and elective mole removal) whenever possible. Any skin problems in predisposed individuals (e.g., acne, infections) should be treated as early as possible to minimize areas of inflammation.

Treatments (both preventive and therapeutic) available are pressure therapy, silicone gel sheeting, intra-lesional triamcinolone acetonide (TAC), cryosurgery (freezing), radiation, laser therapy (PDL), IFN, 5-FU and surgical excision as well as a multitude of extracts and topical agents.[10] Appropriate treatment of a keloid scar is age-dependent: radiotherapy, anti-metabolites and corticosteroids would not be recommended to be used in children, in order to avoid harmful side effects, like growth abnormalities.[11]

In adults, corticosteroids combined with 5-FU and PDL in a triple therapy, enhance results and diminish side effects.[11]

Cryotherapy (or cryosurgery) refers to the application of extreme cold to treat keloids. This treatment method is easy to perform, effective and safe and has the least chance of recurrence.[12][13]

Surgical excision is currently still the most common treatment for a significant amount of keloid lesions. However, when used as the solitary form of treatment there is a large recurrence rate of between 70 and 100%. It has also been known to cause a larger lesion formation on recurrence. While not always successful alone, surgical excision when combined with other therapies dramatically decreases the recurrence rate. Examples of these therapies include but are not limited to radiation therapy, pressure therapy and laser ablation. Pressure therapy following surgical excision has shown promising results, especially in keloids of the ear and earlobe. The mechanism of how exactly pressure therapy works is unknown at present, but many patients with keloid scars and lesions have benefited from it.[5]

Intralesional injection with a corticosteroid such as Kenalog (triamcinolone acetonide) does appear to aid in the reduction of fibroblast activity, inflammation and pruritus.[14]

Tea tree oil, salt or other topical oil has no effect on keloid lesions.[15]

A 2022 systematic review included multiple studies on laser therapy for treating keloid scars. There was not enough evidence for the review authors to determine if laser therapy was more effective than other treatments. They were also unable to conclude if laser therapy leads to more harm than benefits compared with no treatment or different kinds of treatment.[16]

Epidemiology

Persons of any age can develop a keloid. Children under 10 are less likely to develop keloids, even from ear piercing. Keloids may also develop from Pseudofolliculitis barbae; continued shaving when one has razor bumps will cause irritation to the bumps, infection, and over time keloids will form. Persons with razor bumps are advised to stop shaving in order for the skin to repair itself before undertaking any form of hair removal. The tendency to form keloids is speculated to be hereditary.[17] Keloids can tend to appear to grow over time without even piercing the skin, almost acting out a slow tumorous growth; the reason for this tendency is unknown.

Extensive burns, either thermal or radiological, can lead to unusually large keloids; these are especially common in firebombing casualties, and were a signature effect of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

True incidence and prevalence of keloid in United States is not known. Indeed, there has never been a population study to assess the epidemiology of this disorder. In his 2001 publication, Marneros[18] stated that “reported incidence of keloids in the general population ranges from a high of 16% among the adults in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to a low of 0.09% in England,” quoting from Bloom's 1956 publication on heredity of keloids.[19] Clinical observations show that the disorder is more common among sub-Saharan Africans, African Americans and Asians, with unreliable and very wide estimated prevalence rates ranging from 4.5 to 16%.[20][21]

History

Keloids were described by Egyptian surgeons around 1700 BC, recorded in the Smith papyrus, regarding surgical techniques. Baron Jean-Louis Alibert (1768–1837) identified the keloid as an entity in 1806. He called them cancroïde, later changing the name to chéloïde to avoid confusion with cancer. The word is derived from the Ancient Greek χηλή, chele, meaning "crab pincers", and the suffix -oid, meaning "like".

The famous American Civil War-era photograph "Whipped Peter" depicts an escaped former slave with extensive keloid scarring as a result of numerous brutal beatings from his former overseer.

Intralesional corticosteroid injections was introduced as a treatment in mid-1960s as a method to attenuate scaring.[22]

Pressure therapy has been use for prophylaxis and treatment of keloids since the 1970s.[22]

Topical silicone gel sheeting was introduced as a treatment in the early 1980s.[22]

References

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1499. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- Ogawa, Rei (2010). "The Most Current Algorithms for the Treatment and Prevention of Hypertrophic Scars and Keloids". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 125 (2): 557–68. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c82dd5. PMID 20124841. S2CID 21364302.

- Babu, M; Meenakshi, J; Jayaraman, V; Ramakrishnan, KM (2005). "Keloids and hypertrophic scars: A review". Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 38 (2): 175–9. doi:10.4103/0970-0358.19796.

- "Keloid Scar: Find Causes, Symptoms, and Removal". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- Andrews, Jonathan P.; Marttala, Jaana; MacArak, Edward; Rosenbloom, Joel; Uitto, Jouni (2016). "Keloids: The paradigm of skin fibrosis — Pathomechanisms and treatment". Matrix Biology. 51: 37–46. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2016.01.013. PMC 4842154. PMID 26844756.

- Kiprono, S.K.; Chaula, B.M.; Masenga, J.E.; Muchunu, J.W.; Mavura, D.R.; Moehrle, M. (September 2015). "Epidemiology of keloids in normally pigmented Africans and African people with albinism: population-based cross-sectional survey". British Journal of Dermatology. 173 (3): 852–854. doi:10.1111/bjd.13826. PMID 25833201. S2CID 20641975.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001852/%5B%5D

- Ramakrishnan, K. M.; Thomas, K. P.; Sundararajan, C. R. (1974). "Study of 1,000 patients with keloids in South India". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 53 (3): 276–80. doi:10.1097/00006534-197403000-00004. PMID 4813760.

- Wound Healing, Keloids at eMedicine

- Gauglitz, Gerd; Korting, Hans (2011). "Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: Pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies". Molecular Medicine. 17 (1–2): 113–25. doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. PMC 3022978. PMID 20927486.

- Arno, Anna I.; Gauglitz, Gerd G.; Barret, Juan P.; Jeschke, Marc G. (2014). "Up-to-date approach to manage keloids and hypertrophic scars: A useful guide". Burns. 40 (7): 1255–66. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.02.011. PMC 4186912. PMID 24767715.

- Zouboulis, C. C.; Blume, U.; Büttner, P.; Orfanos, C. E. (September 1993). "Outcomes of cryosurgery in keloids and hypertrophic scars. A prospective consecutive trial of case series". Archives of Dermatology. 129 (9): 1146–1151. doi:10.1001/archderm.1993.01680300074011. ISSN 0003-987X. PMID 8363398.

- "Keloid Research Foundation". 2016-11-07. Archived from the original on 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- Griffith, B. H. (1966). "The treatment of keloids with triamcinolone acetonide". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 38 (3): 202–8. doi:10.1097/00006534-196609000-00004. PMID 5919603.

- "Keloid Treatment". Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Leszczynski, Rafael; da Silva, Carolina AP; Pinto, Ana Carolina Pereira Nunes; Kuczynski, Uliana; da Silva, Edina MK (2022-09-26). Cochrane Wounds Group (ed.). "Laser therapy for treating hypertrophic and keloid scars". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (9). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011642.pub2. PMC 9511989.

- Halim, Ahmad Sukari; Emami, Azadeh; Salahshourifar, Iman; Kannan, Thirumulu Ponnuraj (2012). "Keloid Scarring: Understanding the Genetic Basis, Advances, and Prospects". Archives of Plastic Surgery. 39 (3): 184–9. doi:10.5999/aps.2012.39.3.184. PMC 3385329. PMID 22783524.

- Marneros, Alexander G.; Norris, James E. C.; Olsen, Bjorn R.; Reichenberger, Ernst (2001). "Clinical Genetics of Familial Keloids". Archives of Dermatology. 137 (11): 1429–34. doi:10.1001/archderm.137.11.1429. PMID 11708945.

- Bloom, D (1956). "Heredity of keloids; review of the literature and report of a family with multiple keloids in five generations". New York State Journal of Medicine. 56 (4): 511–9. PMID 13288798.

- Froelich K, Staudenmaier R, Kleinsasser N, Hagen R (December 2007). "Therapy of auricular keloids: review of different treatment modalities and proposal for a therapeutic algorithm". Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 264 (12): 1497–508. doi:10.1007/s00405-007-0383-0. PMID 17628822. S2CID 25168874.

- Gauglitz, Gerd; Korting, Hans; Pavicic, T; Ruzicka, T; Jeschke, M. G. (2011). "Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: Pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies". Molecular Medicine. 17 (1–2): 113–25. doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. PMC 3022978. PMID 20927486.

- Gauglitz, Gerd G.; Korting, Hans C.; Pavicic, Tatiana; Ruzicka, Thomas; Jeschke, Marc G. (2010-10-05). "Hypertrophic Scarring and Keloids: Pathomechanisms and Current and Emerging Treatment Strategies". Molecular Medicine. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 17 (1–2): 113–125. doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. ISSN 1076-1551. PMC 3022978. PMID 20927486.

Further reading

- Roßmann, Nico (2005). Beitrag zur Pathogenese des Keloids und seine Beeinflussbarkeit durch Steroidinjektionen [Contribution to the pathogenesis of the keloid and its influence by steroid injections] (PhD Thesis) (in German). OCLC 179740918.

- Ogawa, Rei; Mitsuhashi, Kiyoshi; Hyakusoku, Hiko; Miyashita, Tuguhiro (2003). "Postoperative Electron-Beam Irradiation Therapy for Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars: Retrospective Study of 147 Cases Followed for More Than 18 Months". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 111 (2): 547–53, discussion 554–5. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000040466.55214.35. PMID 12560675. S2CID 8411788.

- Okada, Emi; Maruyama, Yu (2007). "Are Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars Caused by Fungal Infection?". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 120 (3): 814–5. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000278813.23244.3f. PMID 17700144.