Khalil al-Wazir

Khalil Ibrahim al-Wazir[note 1] (Arabic: خليل إبراهيم الوزير, also known by his kunya Abu Jihad[note 2] أبو جهاد—"Jihad's Father"; 10 October 1935 – 16 April 1988) was a Palestinian leader and co-founder of the nationalist party Fatah. As a top aide of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat, al-Wazir had considerable influence in Fatah's military activities, eventually becoming the commander of Fatah's armed wing al-Assifa.

Khalil al-Wazir | |

|---|---|

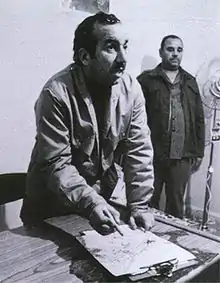

Khalil al-Wazir strategizing | |

| Nickname(s) | Abu Jihad |

| Born | 10 October 1935 Ramla, British Mandate of Palestine |

| Died | 16 April 1988 (aged 52) Tunis, Tunisia |

| Buried | Al Yarmuk camp, Syria |

| Allegiance | Fatah/Palestine Liberation Organization |

| Service/ | Al-Assifa |

| Rank | Commander |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Karameh Black September in Jordan Siege of Beirut First Intifada |

| Relations | Intissar al-Wazir (wife) |

Al-Wazir became a refugee when his family was expelled from Ramla during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and began leading a minor fedayeen force in the Gaza Strip. In the early 1960s he established connections for Fatah with Communist regimes and prominent third-world leaders. He opened Fatah's first bureau in Algeria. He played an important role in the 1970–71 Black September clashes in Jordan, by supplying besieged Palestinian fighters with weapons and aid. Following the PLO's defeat by the Jordanian Army, al-Wazir joined the PLO in Lebanon.

Prior to and during Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon, al-Wazir planned numerous attacks inside Israel against both civilian and military targets. He prepared Beirut's defense against incoming Israeli forces. Nonetheless, the Israeli military prevailed and al-Wazir was exiled from Lebanon with the rest of the Fatah leadership. He settled in Amman for a two-year period and was then exiled to Tunis in 1986. From his base there, he started to organize youth committees in the Palestinian territories; these eventually formed a major component of the Palestinian forces in the First Intifada. However, he did not live to command the uprising. On 16 April 1988, he was assassinated at his home in Tunis by Israeli commandos.

Early life

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

|

| Culture |

|

| List of Palestinians |

Khalil al-Wazir was born in 1935 to Muslim parents in the city of Ramla, Palestine, then under British Mandatory rule. His father, Ibrahim al-Wazir, worked as a grocer in the city.[1][2] Al-Wazir and his family were expelled in July 1948, along with another 50,000–70,000 Palestinians from Lydda and Ramla, following Israel's capture of the area during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[3] They settled in the Bureij refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, where al-Wazir attended a secondary school run by UNRWA.[4] While in high school, he began organizing a small group of fedayeen to harass Israelis at military posts near the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula.[1]

In 1954 he came into contact with Yasser Arafat in Gaza; al-Wazir would become Arafat's right-hand man later in his life. During his time in Gaza, al-Wazir became a member of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood,[5] and was briefly imprisoned for his membership with the organization, as it was prohibited in Egypt.[6] In 1956, a few months after his release from prison, he received military training in Cairo.[2] He also studied architectural engineering at the University of Alexandria,[7] but he did not graduate. Al-Wazir was detained once again in 1957 for leading raids against Israel and was exiled to Saudi Arabia, finding work as a schoolteacher.[1] He continued to teach after moving to Kuwait in 1959.[6]

Formation of Fatah

Al-Wazir used his time in Kuwait to further his ties with Arafat and other fellow Palestinian exiles he had met in Egypt. He and his comrades founded Fatah, a Palestinian nationalist guerrilla and political organization, sometime between 1959 and 1960.[8] He moved to Beirut after being put in charge of editing the newly formed organization's monthly magazine Filastinuna, Nida' al-Hayat ("Our Palestine, the Call to Life"), as he was "the only one with a flair for writing."[8]

He settled in Algeria in 1962, after a delegation of Fatah leaders, including Arafat and Farouk Kaddoumi, were invited there by Algerian President Ahmed Ben Bella. Al-Wazir remained there, opened a Fatah office and military training camp in Algiers and was included in an Algerian-Fatah delegation to Beijing in 1964.[9] During his visit, he presented Fatah's ideas to various leaders of the People's Republic of China, including premier Zhou Enlai,[10] and thus inaugurated Fatah's good relationship with China. He also toured other East Asian countries, establishing relations with North Korea and the Viet Cong.[9] Al-Wazir supposedly "charmed Che Guevara" during Guevara's speech in Algiers.[8] With his guerrilla credentials and his contacts with arms-supplying nations, he was assigned the role of recruiting and training fighters, thus establishing Fatah's armed wing al-Assifa (the Storm).[11] While in Algiers, he recruited Abu Ali Iyad who became his deputy and one of the high-ranking commanders of al-Assifa in Syria and Jordan.[12]

Syria and post-Six-Day War

Al-Wazir and the Fatah leadership settled in Damascus, Syria in 1965, in order take advantage of the large number of Palestine Liberation Army (PLA) members there. On 9 May 1966, he and Arafat were detained by Syrian police loyal to air marshal Hafez al-Assad after an incident where a pro-Syrian Palestinian leader, Yusuf Orabi was thrown out of the window of a three-story building and killed. Al-Wazir and Arafat were either considering uniting Fatah with Orabi's faction—the Revolutionary Front for the Liberation of Palestine—or winning Orabi's support against Arafat's rivals within the Fatah leadership. An argument occurred, eventually leading to Orabi's murder; however, al-Wazir and Arafat had already left the scene shortly before the incident. According to Aburish, Orabi and Assad were "close friends" and Assad appointed a panel to investigate what happened. The panel found both Arafat and al-Wazir guilty, but Salah Jadid, then Deputy Secretary-General of the President of Syria, pardoned them.[8]

After the defeat of a coalition of Arab states in the 1967 Six-Day War, major Palestinian guerrilla organizations that participated in the war or were sponsored by any of the involved Arab states, such as the Arab Nationalist Movement led by George Habash and the Palestine Liberation Army of Ahmad Shukeiri, lost considerable influence among the Palestinian population. This made Fatah the dominant faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). They gained 33 of 105 seats in the Palestinian National Council (PNC) (the most seats allocated to any guerrilla group), thus strengthening al-Wazir's position. During the Battle of Karameh, in March 1968, he and Salah Khalaf held important command positions among Fatah fighters against the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), which developed his credentials as a military strategist.[13] This eventually led to him taking command of al-Assifa, holding major positions in the PNC,[2] and the Supreme Military Council of the PLO. He was also put in charge of guerrilla warfare operations in both the occupied Palestinian territories and Israel proper.[1][11]

Black September and the Lebanon War

During the Black September clashes in Jordan, al-Wazir supplied the encircled Palestinian forces in Jerash and Ajlun with arms and aid,[14] but the conflict was decided in Jordan's favor. After Arafat and thousands of Fatah fighters retreated to Lebanon, al-Wazir negotiated an agreement between King Hussein and the PLO's leading organizer, calling for better Palestinian conduct in Jordan.[15] Then, along with the other PLO leaders, he relocated to Beirut.[14]

Al-Wazir did not play a major role in the Lebanese Civil War; he confined himself primarily to strengthening the Lebanese National Movement, the PLO's main ally in the conflict.[14] During the fall of the Tel al-Zaatar camp to the Lebanese Front, al-Wazir blamed himself for not organizing a rescue effort.[16]

During his time in Lebanon, al-Wazir was responsible for coordinating high-profile operations. He allegedly planned the Savoy Hotel attack in 1975, in which eight Fatah militants raided and took civilian hostages in the Savoy hotel in Tel Aviv, killing eight of them, as well as three Israeli soldiers.[17] The Coastal Road massacre, in March 1978, was also planned by al-Wazir. In this attack, six Fatah members hijacked a bus and killed 35 Israeli civilians.[18]

When Israel besieged Beirut in 1982, al-Wazir, disagreed with the PLO's leftist members and Salah Khalaf; he proposed that the PLO pull out of Beirut. Nevertheless, al-Wazir and his aide Abu al-Walid planned Beirut's defense and helped direct PLO forces against the IDF.[19] PLO forces were eventually defeated and then expelled from Lebanon, with most of the leadership relocating to Tunis, although al-Wazir and 264 other PLO members were received by King Hussein of Jordan.[10][20]

Establishing a movement in the West Bank and Gaza Strip

Dissatisfied at the decisive defeat of Palestinian forces in Lebanon during the 1982 Lebanon War, al-Wazir concentrated on establishing a solid Fatah base in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. In 1982, he began to sponsor youth committees in the territories. These organizations would grow and initiate the First Intifada in December 1987 (the word Intifada in Arabic, literally translated as "shaking off", is generally used to describe an uprising or revolt).

The Intifada began as an uprising of Palestinian youth against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[21] On 7 June 1986, about a year before the Intifada started, al-Wazir was deported from Amman to Baghdad, eventually moving to Tunisia days after King Hussein declared that efforts in establishing a joint strategy for the Israeli–Palestinian conflict between Jordan and the PLO were over.[10]

The first stage of the Intifada took place upon escalation of two unrelated incidents in the Gaza Strip. The first was a traffic incident at the Erez checkpoint, where an Israeli military vehicle hit a group of Palestinian laborers, killing four of them. The funerals, attended by 10,000 people from the camp that evening, quickly led to a large demonstration. Rumours swept the camp that the incident was an act of intentional retaliation for the second event - stabbing to death of an Israeli businessman, killed while shopping in Gaza two days earlier. Following the throwing of a petrol bomb at a passing patrol car in the Gaza Strip on the following day, Israeli forces, firing with live ammunition and tear gas canisters into angry crowds, shot one young Palestinian dead and wounded 16 others.

However, within weeks, following persistent requests by al-Wazir, the PLO attempted to direct the uprising, which lasted until 1991, or 1993, according to various authorities. Al-Wazir had been assigned by Arafat the responsibility of the territories within the PLO command. According to author Said Aburish, he had "impressive knowledge of local conditions" in the Israeli-occupied territories, apparently knowing "every village, school, and large family in Gaza and the West Bank". He provided the uprising with financial backing and logistical support, thus becoming its "brain in exile". Al-Wazir activated every cell he had set up in the territories since the late 1970s in an effort to militarily back the stone-throwers who formed the backbone of the Palestinian revolt. He also used the opportunity to reform the PLO.[21] According to author Yezid Sayigh, al-Wazir believed that the Intifada should not have been sacrificed to Arafat solely for use as a diplomatic or political tool.[22]

Assassination

Al-Wazir was assassinated in his home in Tunis at 1.30 a.m. on 16 April 1988, at the age of 52. There are varying versions of his death. According to one he was shot on the landing of his house by a commando who pursued him upstairs when he ran there after hearing the shots that killed two security guards outside.[23] A different version has it he was working on a memo to leaders of the Intifada, and only had time to fire off one shot from his pistol when the assassination squad burst into his rooms. He was shot at close range, reportedly 70 times, in the presence of his wife Intissar and his son Nidal, above whose bed a commando then fired a burst of automatic fire as a warning.[21][24] Al-Wazir was assassinated by an Israeli commando team, reportedly ferried from Israel by boat, aided ashore by Mossad intelligence operatives, and using the IDs of Lebanese fisherman who had been kidnapped to gain access to the PLO compound.[25] Israel accused al-Wazir of escalating the violence of the Intifada, which was ongoing at the time of his assassination.[21] Specifically, it was claimed he was the architect of the triple bomb attack at a shopping mall. Riots immediately broke out in the Palestinian territories, and at least a dozen Palestinians were shot dead in the worst show of violence since the outbreak of the uprising.[24] He was buried in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus on 21 April;[10] Arafat led the funeral procession.[21]

In 1997, the Maariv newspaper reported on the assassination of al-Wazir. The report claimed that Ehud Barak led a seaborne command center on a navy missile boat off the shore of Tunis that oversaw al-Wazir's assassination. Up until 1 November 2012, Israel however did not take official responsibility for his killing and government spokesman Moshe Fogel and aides to Barak declined to comment on the issue. According to the report, Barak, who was then a deputy military chief, coordinated the planning by the Mossad, as well as the army's intelligence branch, the air force, navy and the elite Sayeret Matkal commando unit. Mossad intelligence agents watched al-Wazir's home for months before the raid.[26] The Washington Post reported on 21 April that the Israeli cabinet approved al-Wazir's assassination on 13 April and that it was coordinated between the Mossad and the IDF.[10]

In 2013, Israel unofficially confirmed that it was responsible for his assassination, after an interview by Israeli correspondent Ronen Bergman of Nahum Lev, the Sayeret Matkal officer who led the raid, was cleared for publication – its release had been blocked by military censors for more than a decade. In that interview, Lev gave Bergman a detailed account of the operation.[27]

The United States Department of State condemned his killing as an "act of political assassination".[28][29] The UN Security Council approved Resolution 611 condemning "the aggression perpetrated against the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Tunisia", without specifically mentioning Israel.[30]

Personal life

Al-Wazir married his cousin Intissar al-Wazir in 1962 and had five children with her. They had three sons, named Jihad, Bassem and Nidal, and two daughters, named Iman and Hanan al-Wazir.[31] Intissar and her children returned to Gaza following the Oslo Accords between Israel and the PLO and in 1996 she became the first female minister in the Palestinian National Authority.[32] His son Jihad al-Wazir is formerly the Governor of the Palestinian Monetary Authority and currently works for the International Monetary Fund.[33]

After Hamas' takeover of the Gaza Strip in 2007, looters raided al-Wazir's home, reportedly stealing his personal belongings. Intissar al-Wazir said that the looting "occurred in broad daylight and under the watchful eye of Hamas militiamen."[34]

See also

- List of Fatah members

Notes

- Standardized Arabic transliteration: Khalīl Ibrāhīm al-Wazīr / Ḫalīl ʾIbrāhīm al-Wazīr / ḵalīl ibrāhīm al-wazīr

- Standardized Arabic transliteration: Abū Jihād

- Cobban, Helena (1984). The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: People, Power, and Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-27216-5.

- Khalil al-Wazir Biography: Article abstract ENotes Incorporate.

- Morris 2004, p. 425.

- "Wazir, Khalil Ibrahim al-." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 7 March 2008

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- "The Fallen Prince −16 Years of the Assassination of Abu Jihad". Archived from the original on 28 June 2004. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) International Press Center. 16 April 2004 - Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 40–67. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- Cobban, Helena (1984). The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: People, Power, and Politics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0-521-27216-5.

- Palestine Facts: 1963–1988 Archived 29 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA)

- Palestine Biography: Khalil al-Wazir Archived 10 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine Shashaa, Esam, Palestine History.

- Sayigh, 1997, p.123.

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 73–85. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- "Encyclopedia of the Palestinians (Facts on File Library of World History)". Phillip Mattar. Vol. 1. Facts on File. 2000. Excerpt provided by palestineremembered.com al-Wazir, Khalil

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 109–133. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 154–155. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- Terrorist Suicide Operation Analysis: Savoy Operation GlobalSecurity, 27 April 2005

- "Israel's successful assassinations" (in Hebrew). MSN. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Khalil al-Wazir (Abu Jihad): The 17th Palestine National Council Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2, Special Issue: The Palestinians in Israel and the Occupied Territories (Winter, 1985), pp. 3–12

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 174–176. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 203–210. ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- Sayigh, Yezid (1997). Armed Struggle and the Search for State, the Palestinian National Movement, 1949–1993. London: Oxford University Press. p. 618. ISBN 0-19-829643-6.

- Edgar O'Ballance, The Palestinian Intifada, Springer 2016 p.46.

- David Pratt Intifada, Casemate Publishers 2007 pp.38-9.

- Anita Vitullo, 'Uprising in Gaza,' in Zachery Lockman, Joel Beinin (eds.), Intifada: The Palestinian Uprising Against Israeli Occupation,South End Press, p.50.

- Ackerman, Gwen (4 July 1997). "Barak Assassination of Abu Jihad". Hartford Web Publishing. Associated Press. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- 24 years later, Israel acknowledges top-secret operation that killed Fatah terror chief

- Chomsky, Noam (January 1996). "A Painful Peace: That's a fair sample". Z-Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- Pear, Robert; Times, Special to The New York (19 April 1988). "U.S. Assails P.L.O. Aide's Killing As 'Act of Political Assassination'". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- List of United Nations Security Council Resolutions on Israel

- For Gazan, Her Return Breeds Hope Greenburg, Joel. The New York Times. 4 August 1994. Accessed on 30 March 2008

- The PA Ministerial Cabinet List November 2003: Biography of PA Cabinet Archived 3 December 2003 at the Wayback Machine Jerusalem Media and Communication Centre

- The Signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between the Central Bank of Jordan and the Palestinian Monetary Authority Archived 11 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Central Bank of Jordan.

- Looters raid Arafat's home, steal his Nobel Peace Prize Khaled Abu Toameh The Jerusalem Post. 16 June 2007 Accessed on 2008-02-22. In 2012 Israel recognizes the killing of Abou Nidal, the assassination was executed by Moussad Commando "Kissiria" and the help of the commando unit Sayeret Matkal (AFP 1 November 2012)

References

- Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). Arafat: From Defender to Dictator. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58234-049-4.

- Cobban, Helena (1984). The Palestinian Liberation Organization. New York: Cambridge University Press Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-521-27216-5.

External links

- "Encyclopedia of the Palestinians: Biography of Khalil al-Wazir (Abu Jihad)", Phillip Mattar.

- "Official Abujihad Site Archived 1 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine", Published By Sidata.

- "ABUJNA Abu Jihad Palestinian News Agency, director founder Abu Faisal Sergio Tapia", Published By Jamal.