La Brea Tar Pits

La Brea Tar Pits is an active paleontological research site in urban Los Angeles. Hancock Park was formed around a group of tar pits where natural asphalt (also called asphaltum, bitumen, or pitch; brea in Spanish) has seeped up from the ground for tens of thousands of years. Over many centuries, the bones of trapped animals have been preserved. The George C. Page Museum is dedicated to researching the tar pits and displaying specimens from the animals that died there. La Brea Tar Pits is a registered National Natural Landmark.

| La Brea Tar Pits | |

|---|---|

Methane gas bubble emerging at La Brea Tar Pits (2004) | |

Location in Los Angeles | |

| Location | Hancock Park, Los Angeles, US |

| Coordinates | 34°03′46″N 118°21′22″W |

| Official website | |

California Historical Landmark | |

| Official name | Hancock Park La Brea[1] |

| Reference no. | 170 |

| Designated | 1964 |

Formation

Tar pits are composed of heavy oil fractions called gilsonite, which seeps from the Earth as oil. Crude oil seeps up along the 6th Street Fault from the Salt Lake Oil Field, which underlies much of the Fairfax District north of Hancock Park.[2] The oil reaches the surface and forms pools, becoming asphalt as the lighter fractions of the petroleum biodegrade or evaporate.[3] The asphalt then normally hardens into stubby mounds. The pools and mounds can be seen in several areas of the park.

This seepage has been happening for tens of thousands of years, during which the asphalt sometimes formed a deposit thick enough to trap animals. The deposit would become covered over with water, dust, or leaves. Animals would wander in, become trapped, and die. Predators would enter to eat the trapped animals and would also become stuck. As the bones of a dead animal sink, the asphalt soaks into them, turning them dark-brown or black in color. Lighter fractions of petroleum evaporate from the asphalt, leaving a more solid substance, which then encases the bones. Dramatic fossils of large mammals have been extricated but the asphalt also preserves microfossils: wood and plant remnants, rodent bones, insects, mollusks, dust, seeds, leaves, and pollen grains.[4] Examples of some of these are on display in the George C. Page Museum. Radiometric dating of preserved wood and bones has given an age of 38,000 years for the oldest known material from the La Brea seeps.

History

The Native American Chumash and Tongva people living in the area built boats unlike any others in North America. Pulling fallen Northern California redwood trunks and pieces of driftwood from the Santa Barbara Channel, their ancestors learned to seal the cracks between the boards of the large wooden plank canoes by using the natural resource of tar. This innovative form of transportation allowed access up and down the coastline and to the Channel Islands. The Portolá expedition, a group of Spanish explorers led by Gaspar de Portolá, made the first written record of the tar pits in 1769. Father Juan Crespí wrote,

While crossing the basin, the scouts reported having seen some geysers of tar issuing from the ground like springs; it boils up molten, and the water runs to one side and the tar to the other. The scouts reported that they had come across many of these springs and had seen large swamps of them, enough, they said, to caulk many vessels. We were not so lucky ourselves as to see these tar geysers, much though we wished it; as it was some distance out of the way we were to take, the Governor [Portolá] did not want us to go past them. We christened them Los Volcanes de Brea [the Tar Volcanoes].[5]

Harrison Rogers, who accompanied Jedediah Smith on his 1826 expedition to California, was shown a piece of the solidified asphalt while at Mission San Gabriel, and noted in his journal, "The Citizens of the Country make great use of it to pitch the roofs of their houses".[6]

The La Brea Tar Pits and Hancock Park are situated within what was once the Mexican land grant of Rancho La Brea. For some years, tar-covered bones were found on the Rancho La Brea property, but were not initially recognized as fossils because the ranch had lost various animals–including horses, cattle, dogs, and even camels–whose bones closely resemble several of the fossil species. The original Rancho La Brea land grant stipulated that the tar pits be open to the public for the use of the local Pueblo. Initially, they mistook the bones in the pits for the remains of pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) or cattle that had become mired.

In 1886, the first excavation for land pitch in the village of La Brea was undertaken by Messrs Turnbull, Stewart & co..[7]

Union Oil geologist W. W. Orcutt is credited, in 1901, with first recognizing that fossilized prehistoric animal bones were preserved in pools of asphalt on the Hancock Ranch. In commemoration of Orcutt's initial discovery, paleontologists named the La Brea coyote (Canis latrans orcutti) in his honor.[8]

John C. Merriam of the University of California led much of the original work in this area early in the 1900s.[3]

Contemporary excavations of the bones started in 1913–1915. In the 1940s and 1950s, public excitement was generated by the preparation of previously recovered large mammal bones.[9] A subsequent study demonstrated the fossil vertebrate material was well preserved, with little evidence of bacterial degradation of bone protein.[10] They are believed to be some 10–20,000 years old, dating from the last glacial period.[11]

Excavation of "Project 23" and newly uncovered pits

On February 18, 2009, George C. Page Museum announced the 2006 discovery of 16 fossil deposits that had been removed from the ground during the construction of an underground parking garage for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art next to the tar pits.[12] Among the finds are remains of a saber-toothed cat, dire wolves, bison, horses, a giant ground sloth, turtles, snails, clams, millipedes, fish, gophers, and an American lion.[12][13] Also discovered is a nearly intact mammoth skeleton, nicknamed Zed; the only pieces missing are a rear leg, a vertebra, and the top of its skull, which was sheared off by construction equipment in preparation to build the parking structure.[13][14][15]

These fossils were packaged in boxes at the construction site and moved to a compound behind Pit 91, on Page Museum property, so that construction could continue. Twenty-three large accumulations of tar and specimens were taken to the Page Museum. These deposits are worked on under the name "Project 23". As work for the public transit D Line is extended, museum researchers know more tar pits will be uncovered, for example near the intersection of Wilshire and Curson.[12] In an exploratory subway dig in 2014 on the Miracle Mile, prehistoric objects unearthed included geoducks, sand dollars, and a 10-foot limb (3.0 m) from a pine tree, of a type now found in Central California's woodlands.[16]

George C. Page Museum

In 1913, George Allan Hancock, the owner of Rancho La Brea, granted the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County exclusive excavation rights at the Tar Pits for two years. In those two years, the museum was able to extract 750,000 specimens at 96 sites, guaranteeing that a large collection of fossils would remain consolidated and available to the community.[17] Then in 1924, Hancock donated 23 acres (9.3 ha) to LA County with the stipulation that the county provide for the preservation of the park and the exhibition of fossils found there.[17]

The George C. Page Museum of La Brea Discoveries, part of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, was built next to the tar pits in Hancock Park on Wilshire Boulevard. Construction began in 1975, and the museum opened to the public in 1977.[18] The area is part of urban Los Angeles in the Miracle Mile District.

The museum tells the story of the tar pits and presents specimens excavated from them. Visitors can walk around the park and see the tar pits. On the grounds of the park are life-sized models of prehistoric animals in or near the tar pits. Of more than 100 pits, only Pit 91 is still regularly excavated by researchers and can be seen at the Pit 91 viewing station. In addition to Pit 91, the one other ongoing excavation is called "Project 23". Paleontologists supervise and direct the work of volunteers at both sites.[19]

As a result of a design competition in 2019, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County chose Weiss/Manfredi over Dorte Mandrup and Diller Scofidio + Renfro to redesign the park, including by adding a 3,281-foot-long pedestrian walkway framing Lake Pitt.[20]

Flora and fauna

Among the prehistoric species associated with the La Brea Tar Pits are Pleistocene mammoths, dire wolves, short-faced bears, American lions, ground sloths, and, the state fossil of California, the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis).

The park is known for producing myriad mammal fossils dating from the last glacial period. While mammal fossils generate significant interest, other fossils, including fossilized insects and plants, and even pollen grains, are also valued. These fossils help define a picture of what is thought to have been a cooler, moister climate in the Los Angeles basin during the glacial age. Microfossils are retrieved from the matrix of asphalt and sandy clay by washing with a solvent to remove the petroleum, then picking through the remains under a high-powered lens.

Tar pits around the world are unusual in accumulating more predators than prey. The reason for this is unknown, but one theory is that a large prey animal would die or become stuck in a tar pit, attracting predators across long distances. This predator trap would catch predators along with their prey. Another theory is that dire wolves and their prey were trapped during a hunt. Since modern wolves hunt in packs, each prey animal could take several wolves with it. The same may be true of saber-toothed cats known from the area. The most common animals from this area included dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, coyotes, ancient bison, and Jefferson's ground sloth.[21][22][23][24]

Bacteria

Methane gas escapes from the tar pits, causing bubbles that make the asphalt appear to boil. Asphalt and methane appear under surrounding buildings and require special operations for removal to prevent the weakening of building foundations. In 2007, researchers from UC Riverside discovered that the bubbles were caused by hardy forms of bacteria embedded in the natural asphalt. After consuming petroleum, the bacteria release methane. Around 200 to 300 species of bacteria were newly discovered here.[25]

Human presence

Only one human has been found, a partial skeleton of the La Brea Woman[26] dated to around 10,000 calendar years (about 9,000 radiocarbon years) BP,[27] who was 17 to 25 years old at death[28] and found associated with remains of a domestic dog, so was interpreted to have been ceremonially interred.[29] In 2016, however, the dog was determined to be much younger in date.[30]

Also, some even older fossils showed possible tool marks, indicating humans active in the area at the time. Saber-toothed cat bones from La Brea showing signs of ‘artificial’ cut marks at oblique angles to the long axis of each bone were radiocarbon dated to 15,200 ± 800 B.P. (uncalibrated).[31]

If these cuts are in fact tool marks resultant from butchering activities, then this material would provide the earliest solid evidence for human association with the Los Angeles Basin. Yet it is also possible that there was some residual contamination of the material as a result of saturation by asphaltum, influencing the radiocarbon dates.[32]

Gallery

Tar and wild flower run within La Brea campus (2014)

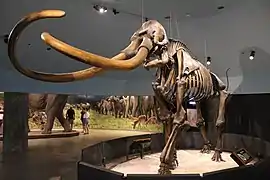

Tar and wild flower run within La Brea campus (2014) Columbian mammoth skeleton from the tar pits, displayed in the George C. Page Museum

Columbian mammoth skeleton from the tar pits, displayed in the George C. Page Museum Saber-toothed cat display

Saber-toothed cat display Fossil crate (2021)

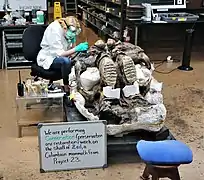

Fossil crate (2021) Lab technician working on recent specimen ZED (2021)

Lab technician working on recent specimen ZED (2021) Lab technician doing a 3-D scan of a fossil (2021)

Lab technician doing a 3-D scan of a fossil (2021)

See also

- Binagadi asphalt lake

- Carpinteria Tar Pits

- Lagerstätten

- Lake Bermudez

- List of fossil sites

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- McKittrick Tar Pits

- Pitch Lake

References

- "Hancock Park". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- Khilyuk, Leonid F.; Chilingar, George V. (2000). Gas migration: events preceding earthquakes. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 389. ISBN 0-88415-430-0.

- "La Brea Tar Pits". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- Purtill, Corinne (October 28, 2022). "'A story of extinction.' La Brea Tar Pits recognized as a geological heritage site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- Kielbasa, John R. (1998). "Rancho La Brea". Historic Adobes of Los Angeles County. Pittsburg: Dorrance Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8059-4172-X..

- Smith, J. S., & Brooks, G. R. (1977). The Southwest expedition of Jedediah S. Smith: His personal account of the journey to California, 1826–1827. Glendale, Calif: A. H. Clark, p. 239. ISBN 0-8706-2123-8

- Mineral Resources of the United States. (1894). United States: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- "Horticulture Centers and Gardens | City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks". www.laparks.org. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Animal Bones 50,000 Years Old Found In Tar". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. June 17, 1946. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- McMenamin, M.A.S.; et al. (1982). "Amino acid geochemistry of fossil bones from the Rancho La Brea Asphalt Deposit, California". Quaternary Research. 18 (2): 174–83. Bibcode:1982QuRes..18..174M. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(82)90068-0.

- Ley, Willy (December 1963). "The Names of the Constellations". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 90–99.

- "Cache Of Ice Age Fossils Found Near Tar Pits". Los Angeles: KCBS-TV. Associated Press. February 18, 2009. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- Thomas H. Maugh II (February 18, 2009). "Major cache of fossils unearthed in L.A." Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- "Workers Unearth Mammoth Discovery near La Brea Tar Pits". Los Angeles: KTLA. February 18, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- "Nearly intact mammoth found at L.A. construction site". USA Today. February 18, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- Malkin, Bonnie (March 7, 2014). "Prehistoric objects unearthed in LA subway dig". The Telegraph (UK). AP. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- "La Brea Tar Pits History | La Brea Tar Pits". tarpits.org. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Page Museum. "About the museum". Page Museum web site. The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Foundation. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- Page Museum. "Page Museum—La Brea Tar Pits". Page Museum web site. The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Foundation. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

- Shane Reiner-Roth (December 12, 2019), WEISS/MANFREDI win competition to master plan the La Brea Tar Pits The Architect's Newspaper.

- "Mammal Collections". La Brea Tar Pits & Museum. Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- Ojibwa (February 21, 2018). "Paleontology 101: Bison and Camels at the La Brea Tar Pits". Daily Kos. Kos Media, LLC. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- Ojibwa (December 13, 2017). "Paleontology 101: The Dire Wolf". Daily Kos. Kos Media, LLC. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- Udurawane, Vasika; Lacerda, Julio (2016). "Trapped in tar: The Ice Age animals of Rancho La Brea". Earth Archives. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- Jia-Rui Chong, "Researchers learn why tar pits are bubbly", Los Angeles Times, May 14, 2007.

- J.C. Merriam (1914) Preliminary report on the discovery of human remains in an asphalt deposit at Rancho La Brea, Science 40: 197–203

- F.R. O'Keefe, E.V. Fet, and J.M. Harris (2009) Compilation, calibration, and synthesis of faunal and floral radiocarbon dates, Rancho La Brea, California, Contributions in Science 518: 1–16

- G.E. Kennedy (1989) A note on the ontogenetic age of the Rancho La Brea hominid, Los Angeles, California, Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences 88(3): 123–26

- R.L. Reynolds (1985) Domestic dog associated with human remains at Rancho La Brea, Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences 84(2): 76–85

- Fuller, Benjamin T.; Southon, John R.; Fahrni, Simon M.; Harris, John M.; Farrell, Aisling B.; Takeuchi, Gary T.; Nehlich, Olaf; Richards, Michael P.; Guiry, Eric J.; Taylor, R. E. (2016). "Tar Trap: No Evidence of Domestic Dog Burial with "La Brea Woman"". PaleoAmerica. 2: 56–59. doi:10.1179/2055557115Y.0000000011. S2CID 130862425.

- Moratto, M. 1984. California Archaeology. Florida: Academic Press, p.54

- Technical report for power plant construction. CULTURAL RESOURCES. California Energy Commission, Sacramento, California, December 2000