Rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Philippines, where Tanduay is the largest producer of rum globally.[1][2][3]

Golden rum with glass | |

| Type | Distilled beverage |

|---|---|

| Region of origin | Caribbean |

| Introduced | 17th century |

| Alcohol by volume | 40–80% |

| Proof (US) | 80–160° |

| Colour | Clear, brown, black, red or golden |

| Flavour | Sweet to dry |

| Ingredients | sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice; yeast; water |

| Variants | rhum agricole, ron miel, tafia |

| Related products | cachaça, charanda, clairin, grogue, grog, Seco Herrerano |

Rums are produced in various grades. Light rums are commonly used in cocktails, whereas "golden" and "dark" rums were typically consumed straight or neat, iced ("on the rocks"), or used for cooking, but are now commonly consumed with mixers. Premium rums are made to be consumed either straight or iced.

Rum plays a part in the culture of most islands of the West Indies as well as the Maritime provinces and Newfoundland, in Canada. The beverage has associations with the Royal Navy (where it was mixed with water or beer to make grog) and piracy (where it was consumed as bumbo). Rum has also served as a medium of economic exchange, used to help fund enterprises such as slavery (see Triangular trade), organized crime, and military insurgencies (e.g., the American Revolution and Australia's Rum Rebellion).

Etymology

The origin of the word "rum" is unclear. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that it is related to "rumbullion", a beverage made from boiling sugar cane stalks,[4] or possibly "rumbustion," which was a slang word for "uproar" or "tumult";[5] a noisy uncontrollable exuberance,[4] though the origin of those words and the nature of the relationship are unclear.[6][7][8][5] Both words surfaced in English about the same time as rum did (1651 for "rumbullion", and before 1654 "rum").[7]

There have been various other theories:

- It is often connected to the British slang adjective "rum", meaning "high quality", and indeed the collocation "rum booze" is attested.[6] Given the harshness of early rum, this is unlikely.[5]

- That it is related to ramboozle and rumfustian, popular British drinks of the mid-17th century. However, neither was made with rum, but rather eggs, ale, wine, sugar, and various spices.

- That it comes from the large drinking glasses used by Dutch seamen known as rummers, from the Dutch word roemer, a drinking glass.[9]

- Other theories consider it to be short for iterum, Latin for "again; a second time", or arôme, French for aroma.[10]

Regardless of the original source, the name was already in common use by 1654, when the General Court of Connecticut ordered the confiscations of "whatsoever Barbados liquors, commonly called rum, kill devil and the like".[11] A short time later in May 1657, the General Court of Massachusetts also decided to make illegal the sale of strong liquor "whether knowne by the name of rumme, strong water, wine, brandy, etc".[10]

In current usage, the name used for a rum is often based on its place of origin.

For rums from places mostly in Latin America where Spanish is spoken, the word ron is used. A ron añejo ("aged rum") is a premium spirit.

Rhum is the term that typically distinguishes rum made from fresh sugar cane juice from rum made from molasses in French-speaking locales like Martinique.[12] A rhum vieux ("old rum") is an aged French rum that meets several other requirements.

Some of the many other names for rum are Nelson's blood, kill-devil, demon water, pirate's drink, navy neaters, and Barbados water.[13] A version of rum from Newfoundland is referred to by the name screech, while some low-grade West Indies rums are called tafia.[14]

History

Origins

Shidhu, a drink produced by fermentation and distillation of sugarcane juice, is mentioned in Sanskrit texts.[15] Maria Dembinska states that the King, Peter I of Cyprus, also called Pierre I de Lusignan (9 October 1328 – 17 January 1369), brought rum with him as a gift for the other royal dignitaries at the Congress of Kraków, held in 1364.[16] This is plausible given the position of Cyprus as a significant producer of sugar in the Middle Ages,[17] although the alcoholic sugar drink named rum by Dembinska may not have resembled modern distilled rums very closely. Dembinska also suggests Cyprus rum was often drunk mixed with an almond milk drink, also produced in Cyprus, called soumada.[18]

Another early rum-like drink is brum. Produced by the Malay people, that beverage dates back thousands of years.[19] Marco Polo also recorded a 14th-century account of a "very good wine of sugar(cane)" that was offered to him in the area that became modern-day Iran.[4]

The first distillation of rum in the Caribbean took place on the sugarcane plantations there in the 17th century. Plantation slaves discovered that molasses, a by-product of the sugar refining process, could be fermented into alcohol. Then, distillation of these alcoholic byproducts concentrated the alcohol, and removed some impurities, producing the first modern rums. Tradition suggests this type of rum first originated on the island of Nevis. A 1651 document[20] from Barbados stated:

"The chief fuddling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor."

However, rum production was also recorded in Brazil in the 1520s,[21] and many historians believe that rum found its way to Barbados along with sugarcane and its cultivation methods from Brazil.[22] A liquid identified as rum has been found in a tin bottle found on the Swedish warship Vasa, which sank in 1628.[23]

By the late 17th century rum had replaced French brandy as the exchange-alcohol of choice in the triangle trade. Canoemen and guards on the African side of the trade, who had previously been paid in brandy, were now paid in rum.[22]

Colonial North America

After development of rum in the Caribbean, the drink's popularity spread to Colonial North America. To support the demand for the drink, the first rum distillery in the Thirteen Colonies was set up in 1664 on Staten Island. Boston, Massachusetts had a distillery three years later.[24] The manufacture of rum became early colonial New England's largest and most prosperous industry.[25] New England became a distilling center due to the technical, metalworking and cooperage skills and abundant lumber; the rum produced there was lighter, more like whiskey. Much of the rum was exported, distillers in Newport, R.I. even made an extra strong rum specifically to be used as a slave currency.[22] Rhode Island rum even joined gold as an accepted currency in Europe for a period of time.[26] While New England triumphed on price and consistency Europeans still viewed the best rums as coming from the Caribbean.[22] Estimates of rum consumption in the American colonies before the American Revolutionary War had every man, woman, or child drinking an average of 3 imperial gallons (14 l) of rum each year.[27]

In the 18th century ever increasing demands for sugar, molasses, rum, and slaves led to a feedback loop which intensified the triangular trade.[28] When France banned the production of rum in their New World possessions to end the domestic competition with brandy, New England distillers were then able to undercut producers in the British West Indies by buying cut rate molasses from French sugar plantations. Outcry from the British rum industry led to the Molasses Act of 1733 which levied a prohibitive tax on molasses imported into the Thirteen Colonies from foreign countries or colonies. Rum at this time accounted for approximately 80% of New England’s exports and paying the duty would have put the distilleries out of business: as a result, both compliance with and enforcement of the act were minimal.[22] Strict enforcement of the Molasses Act’s successor, the Sugar Act, in 1764 may have helped cause the American Revolution.[27] In the slave trade, rum was also used as a medium of exchange. For example, the slave Venture Smith (whose history was later published) had been purchased in Africa, for four gallons of rum plus a piece of calico.

In "The Doctor's Secret Journal", an account of the happenings at Fort Michilimackinac in northern Michigan from 1769 to 1772 by Daniel Morison, a surgeon's mate, noted that there was not much for the men to do and drinking rum was very popular.[29] In fact, Ensign Robert Johnstone, one of the officers, "thought proper to turn trader by selling (the) common rum to the soldiers & all others by whom he might gain a penny in this clandestine Manner." To conceal this theft, "he was observed to have filled up several Barrels of common rum with boiling water to make up the Leakage."[30] Ensign Johnstone had no trouble selling this diluted rum.

The popularity of rum continued after the American Revolution; George Washington insisting on a barrel of Barbados rum at his 1789 inauguration.[31]

Rum started to play an important role in the political system; candidates attempted to influence the outcome of an election through their generosity with rum. The people would attend the hustings to see which candidate appeared more generous. The candidate was expected to drink with the people to show he was independent and truly a republican.[32][33]

Eventually the restrictions on sugar imports from the British West Indies, combined with the development of American whiskeys, led to a decline in the drink's popularity in North America.

Naval rum

Rum's association with piracy began with English privateers' trading in the valuable commodity. Some of the privateers became pirates and buccaneers, with a continuing fondness for rum; the association between the two was only strengthened by literary works such as Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island.[34]

The association of rum with the Royal Navy began in 1655, when a Royal Navy fleet captured the island of Jamaica. With the availability of domestically produced rum, the British changed the daily ration of liquor given to seamen from French brandy to rum.[35]

Navy rum was originally a blend mixed from rums produced in the West Indies. It was initially supplied at a strength of 100 degrees (UK) proof, 57% alcohol by volume (ABV), as that was the only strength that could be tested (by the gunpowder test) before the invention of the hydrometer.[36] The term "Navy strength" is used in modern Britain to specify spirits bottled at 57% ABV.[36]

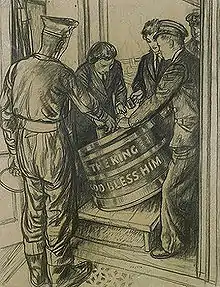

While the ration was originally given neat, or mixed with lime juice, the practice of watering down the rum began around 1740. To help minimize the effect of the alcohol on his sailors, Admiral Edward Vernon had the rum ration watered, producing a mixture that became known as grog. Many believe the term was coined in honour of the grogram cloak Admiral Vernon wore in rough weather.[37] The Royal Navy continued to give its sailors a daily rum ration, known as a "tot", until the practice was abolished on 31 July 1970.[38]

Today, a tot (totty) of rum is still issued on special occasions, using an order to "splice the mainbrace", which may only be given by a member of the royal family or, on certain occasions, the admiralty board in the UK, with similar restrictions in other Commonwealth navies.[39] Recently, such occasions have included royal marriages or birthdays, or special anniversaries. In the days of daily rum rations, the order to "splice the mainbrace" meant double rations would be issued.

A legend involving naval rum and Horatio Nelson says that following his victory and death at the Battle of Trafalgar, Nelson's body was preserved in a cask of rum to allow transportation back to England. Upon arrival, however, the cask was opened and found to be empty of rum. The [pickled] body was removed and, upon inspection, it was discovered that the sailors had drilled a hole in the bottom of the cask and drunk all the rum, hence the term "Nelson's blood" being used to describe rum. It also serves as the basis for the term tapping the admiral being used to describe surreptitiously sucking liquor from a cask through a straw. The details of the story are disputed, as many historians claim the cask contained French brandy, whilst others claim instead the term originated from a toast to Admiral Nelson.[40] Variations of the story, involving different notable corpses, have been in circulation for many years. The official record states merely that the body was placed in "refined spirits" and does not go into further detail.[41]

The Royal New Zealand Navy was the last naval force to give sailors a free daily tot of rum. The Royal Canadian Navy still gives a rum ration on special occasions; the rum is usually provided out of the commanding officer's fund, and is 150 proof (75%). The order to "splice the mainbrace" (i.e. take rum) can be given by the Queen as commander-in-chief, as occurred on 29 June 2010, when she gave the order to the Royal Canadian Navy as part of the celebration of their 100th anniversary.

Colonial Australia

Rum became an important trade good in the early period of the colony of New South Wales. The value of rum was based upon the lack of coinage among the population of the colony, and due to the drink's ability to allow its consumer to temporarily forget about the lack of creature comforts available in the new colony. The value of rum was such that convict settlers could be induced to work the lands owned by officers of the New South Wales Corps. Due to rum's popularity among the settlers, the colony gained a reputation for drunkenness, though their alcohol consumption was less than levels commonly consumed in England at the time.[42]

Australia was so far away from Britain that the penal colony, established in 1788, faced severe food shortages, compounded by poor conditions for growing crops and the shortage of livestock. Eventually it was realized that it might be cheaper for India, instead of Britain, to supply the settlement of Sydney. By 1817, two out of every three ships which left Sydney went to Java or India, and cargoes from Bengal fed and equipped the colony. Casks of Bengal Rum (which was reputed to be stronger than Jamaican Rum, and not so sweet) were brought back in the depths of nearly every ship from India. The cargoes were floated ashore clandestinely before the ships docked, by the Royal Marines regiment which controlled the sales. It was against the direct orders of the governors, who had ordered the searching of every docking ship. British merchants in India grew wealthy through sending ships to Sydney "laden half with rice and half with bad spirits".[43]

Rum was intimately involved in the only military takeover of an Australian government, known as the Rum Rebellion. When William Bligh became governor of the colony, he attempted to remedy the perceived problem with drunkenness by outlawing the use of rum as a medium of exchange. In response to Bligh's attempt to regulate the use of rum, in 1808, the New South Wales Corps marched with fixed bayonets to Government House and placed Bligh under arrest. The mutineers continued to control the colony until the arrival of Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810.[44]

Asia

Commercial rum production was introduced into Taiwan along with commercial sugar production during the Japanese colonial period. Rum production continued under the Republic of China however it was neglected by Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation which held the national liquor monopoly.[3] The industry diversified after democratization and the de-monopolization of the Taiwanese alcoholic beverage industry.[45]

Categorization

Dividing rum into meaningful groupings is complicated because no single standard exists for what constitutes rum. Instead, rum is defined by the varying rules and laws of the nations producing the spirit. The differences in definitions include issues such as spirit proof, minimum ageing, and even naming standards.

Mexico requires rum be aged a minimum of eight months; the Dominican Republic, Panama and Venezuela require two years. Naming standards also vary. Argentina defines rums as white, gold, light, and extra light. Grenada and Barbados uses the terms white, overproof, and matured, while the United States defines rum, rum liqueur, and flavored rum.[46] In Australia, rum is divided into dark or red rum (underproof known as UP, overproof known as OP, and triple distilled) and white rum.

Despite these differences in standards and nomenclature, the following divisions are provided to help show the wide variety of rums produced.

Regional variations

Within the Caribbean, each island or production area has a unique style. For the most part, these styles can be grouped by the language traditionally spoken. Due to the overwhelming influence of Puerto Rican rum, most rum consumed in the United States is produced in the "Spanish-speaking" style.

- English-speaking areas are known for darker rums with a fuller taste that retains a greater amount of the underlying molasses flavor. Rums from the Bahamas, Antigua, Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, Belize, Bermuda, Saint Kitts, the Demerara region of Guyana, and Jamaica are typical of this style. A version called "Rude Rum" or "John Crow Batty" is served in some places and it is reportedly much stronger in alcohol content being listed as one of the 10 strongest drinks in the world, while it might also contain other intoxicants.[47] The term, denoting home made, strong rum, appears in New Zealand since at least the early 19th century.[48] Jamaican rum was granted geographical indication protection in 2016.[49]

- French-speaking areas are best known for their agricultural rums (rhum agricole). These rums, being produced exclusively from sugar cane juice, retain a greater amount of the original flavor of the sugar cane and are generally more expensive than molasses-based rums. Rums from Haiti, Guadeloupe, and Martinique are typical of this style.

- Areas that had been formerly part of the Spanish Empire traditionally produce añejo rums with a fairly smooth taste. Rums from Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela are typical of this style. Rum from the U.S. Virgin Islands is also of this style. The Canary Islands produces a honey-based rum known as ron miel de Canarias which carries a protected geographical designation.

Cachaça is a spirit similar to rum that is produced in Brazil. Some countries, including the United States, classify cachaça as a type of rum. Seco, from Panama, is also a spirit similar to rum, but also similar to vodka since it is triple distilled.

Mexico produces a number of brands of light and dark rum, as well as other less-expensive flavored and unflavored sugarcane-based liquors, such as aguardiente de caña and charanda. Aguardiente is also the name for unaged distilled cane spirit in some, primarily Spanish-speaking countries, since their definition of rum includes at least two years of ageing in wood.

A spirit known as aguardiente, distilled from molasses and often infused with anise, with additional sugarcane juice added after distillation, is produced in Central America and northern South America.[50]

In West Africa, and particularly in Liberia, 'cane juice' (also known as Liberian rum[51] or simply CJ within Liberia itself[52]) is a cheap, strong spirit distilled from sugarcane, which can be as strong as 43% ABV (86 proof).[53] A refined cane spirit has also been produced in South Africa since the 1950s, simply known as cane or "spook".

Within Europe, in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, a similar spirit made from sugar beet is known as Tuzemak.

In Germany, a cheap substitute for genuine dark rum is called Rum-Verschnitt (literally: blended or "cut" rum). This drink is made of genuine dark rum (often high-ester rum from Jamaica), rectified spirit, and water. Very often, caramel coloring is used, too. The relative amount of genuine rum it contains can be quite low, since the legal minimum is at only 5%. In Austria, a similar rum called Inländerrum or domestic rum is available. However, Austrian Inländerrum is always a spiced rum, such as the brand Stroh; German Rum-Verschnitt, in contrast, is never spiced or flavored.

Grades

The grades and variations used to describe rum depend on the location where a rum was produced. Despite these variations, the following terms are frequently used to describe various types of rum:

- Dark rums, also known by their particular colour, such as brown, black, or red rums, are classes a grade darker than gold rums. They are usually made from caramelized sugar or molasses. They are generally aged longer, in heavily charred barrels, giving them much stronger flavors than either light or gold rums, and hints of spices can be detected, along with a strong molasses or caramel overtone. They commonly provide substance in rum drinks, as well as colour. In addition, dark rum is the type most commonly used in cooking. Most dark rums come from areas such as Jamaica, Bahamas, Haiti, and Martinique.

- Flavored rums are infused with flavors of fruits, such as banana, mango, orange, pineapple, coconut, starfruit or lime. These are generally less than 40% ABV (80 proof). They mostly serve to flavor similarly-themed tropical drinks but are also often drunk neat or with ice. This infusion of flavors occurs after fermentation and distillation. Various chemicals are added to the alcohol to simulate the tastes of food.

- Gold rums, also called "amber" rums, are medium-bodied rums that are generally aged. These gain their dark colour from aging in wooden barrels (usually the charred, white oak barrels that are the byproduct of Bourbon whiskey). They have more flavor and are stronger-tasting than light rum, and can be considered midway between light rum and the darker varieties.

- Light rums, also referred to as "silver" or "white" rums, in general, have very little flavor aside from a general sweetness. Light rums are sometimes filtered after aging to remove any colour. The majority of light rums come from Puerto Rico. Their milder flavors make them popular for use in mixed drinks, as opposed to drinking them straight. Light rums are included in some of the most popular cocktails including the Mojito and the Daiquiri.

- Overproof rums are much higher than the standard 40% ABV (80 proof), with many as high as 75% (150 proof) to 80% (160 proof) available. Two examples are Bacardi 151 or Pitorro moonshine. They are usually used in mixed drinks.

- Premium rums, as with other sipping spirits such as Cognac and Scotch whisky, are in a special market category. These are generally from boutique brands that sell carefully produced and aged rums. They have more character and flavor than their "mixing" counterparts and are generally consumed straight.

- Spiced rums obtain their flavors through the addition of spices and, sometimes, caramel. Most are darker in colour, and based on gold rums. Some are significantly darker, while many cheaper brands are made from inexpensive white rums and darkened with caramel colour. Among the spices added are cinnamon, rosemary, absinthe/aniseed, pepper, cloves, and cardamom.

Production method

Unlike some other spirits, rum has no defined production methods. Instead, rum production is based on traditional styles that vary between locations and distillers.

Harvesting

Sugarcane is traditionally collected by sugarcane machete[54] cutters who cut the cane near to the ground, where the largest concentration of sugars is found, before lopping off the green tips. A good cutter can cut three tons of cane per day on average, but this is a small fraction of what a machine can cut, therefore mechanised harvesting is now utilized.

Extraction

Sugarcane comprises around 63% to 73% water, 12% to 16% soluble sugar, 2% to 3% non-sugars, and 11% to 16% fiber.[55] To extract the water and sugar juice, the harvested cane is cleaned, sliced into small lengths, and milled (pressed).

Fermentation

Most rum is produced from molasses, which is made from sugarcane. A rum's quality is dependent on the quality and variety of the sugar cane that was used to create it. The sugar cane's quality depends on the soil type and climate that it was grown in. Within the Caribbean, much of this molasses is from Brazil.[31] A notable exception is the French-speaking islands, where sugarcane juice is the preferred base ingredient.[4] In Brazil itself, the distilled alcoholic drink derived from cane juice is distinguished from rum and called cachaça.[56]

Yeast and water are added to the base ingredient to start the fermentation process. While some rum producers allow wild yeasts to perform the fermentation, most use specific strains of yeast to help provide a consistent taste and predictable fermentation time.[57] Dunder, the yeast-rich foam from previous fermentations, is the traditional yeast source in Jamaica.[58] "The yeast employed will determine the final taste and aroma profile," says Jamaican master blender Joy Spence.[4] Distillers that make lighter rums, such as Bacardi, prefer to use faster-working yeasts.[4] Use of slower-working yeasts causes more esters to accumulate during fermentation, allowing for a fuller-tasting rum.[57]

Fermentation products like 2-ethyl-3-methyl butyric acid and esters like ethyl butyrate and ethyl hexanoate give rise to the sweet and fruitiness of rum.[59]

Distillation

As with all other aspects of rum production, no standard method is used for distillation. While some producers work in batches using pot stills, most rum production is done using column still distillation.[57] Pot still output contains more congeners than the output from column stills, so produces fuller-tasting rums.[4]

Ageing and blending

Many countries require rum to be aged for at least one year.[60] This ageing is commonly performed in used bourbon casks,[57] but may also be performed in other types of wooden casks or stainless steel tanks. The ageing process determines the colour of the rum. When aged in oak casks, it becomes dark, whereas rum aged in stainless steel tanks remains virtually colourless.

Due to the tropical climate, common to most rum-producing areas, rum matures at a much higher rate than is typical for whisky or brandy. An indication of this higher rate is the angels' share, or amount of product lost to evaporation. While products aged in France or Scotland see about 2% loss each year, tropical rum producers may see as much as 10%.[57]

After ageing, rum is normally blended to ensure a consistent flavour, the final step in the rum-making process.[61] During blending, light rums may be filtered to remove any colour gained during ageing. For dark rums, caramel may be added for colour.

There have been attempts to match the molecular composition of aged rum in significantly shorter time spans with artificial aging using heat and light.[62]

In cuisine

Besides rum punches, cocktails such as the Cuba libre and daiquiri have stories of their invention in the Caribbean. Tiki culture in the U.S. helped expand rum's horizons with inventions such as the mai tai and zombie. Other cocktails containing rum include the piña colada, a drink made popular in America by Rupert Holmes' song "Escape (The Piña Colada Song)",[63] and the mojito. Cold-weather drinks made with rum include the rum toddy and hot buttered rum.[64]

A number of local specialties also use rum, including Bermuda's Dark 'n' Stormy (Gosling's Black Seal rum with ginger beer), the Painkiller from the British Virgin Islands, and a New Orleans cocktail known as the Hurricane. Jagertee is a mixture of rum and black tea popular in colder parts of Central Europe and served on special occasions in the British Army, where it is called Gunfire. Ti' Punch, French Creole for "petit punch", is a traditional drink in parts of the French West Indies.

Rum may also be used as a base in the manufacture of liqueurs and syrups, such as falernum and most notably, Mamajuana.

Rum is used in a number of cooked dishes as a flavoring agent in items such as rum balls or rum cakes. It is commonly used to macerate fruit used in fruitcakes and is also used in marinades for some Caribbean dishes. Rum is also used in the preparation of rumtopf, bananas Foster and some hard sauces. Rum is sometimes mixed into ice cream, often with raisins, and in baking it is occasionally used in Joe Froggers, a type of cookie from New England.

See also

- Alcohol (drug)

- Cachaça

- Charanda

- Clairin

- List of rum producers

- Rhum agricole

- Mamajuana

- Rum cake

- Rum cocktails

- Rum row

- Rum-running

- Tafia

References

- "Leading rum brands worldwide based on sales volume 2019". Statista. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- Brick, Jason (16 March 2016). "The world's best rum comes from these countries". Thrillist. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- du Toit, Nick (29 July 2011). "Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of Koxinga Gold rum". taiwantoday.tw. Taiwan Today. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Pacult, F. Paul (July 2002). "Mapping Rum By Region". Wine Enthusiast Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- Curtis (2006), pp. 34-35

- Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2011, s.v. 'rum, adj.1 '

- Anatoly Liberman, "The Rum History of the Word 'Rum'", OUPblog October 6, 2010 Archived 26 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2011, s.v. 'rum, adj.1 ', s.v. 'rumbullion'

- Blue, p. 72-73

- Blue p. 73

- "The West Indies Rum Distillery Limited". WIRD Ltd. 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- Wayne Curtis. "The Five Biggest Rum Myths". Liquor.com.

- Rajiv. M (12 March 2003). "A Caribbean drink". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- Curtis (2006), p.14

- Achaya, K. T. (1994). Indian Food Tradition A Historical Companion. Oxford University Press. pp. 59, 60. ISBN 978-0195644166.

- Maria Dembinska, Food and Drink in Medieval Poland: Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1999) p. 41

- J. H. Galloway, 'The Mediterranean Sugar Industry' in Geographical Review Vol. 67, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), p. 190

- Maria Dembinska, Food and Drink in Medieval Poland: Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1999) p. 41

- Blue p. 72

- Blue p. 70

- Cavalcante, Messias Soares. A verdadeira história da cachaça. São Paulo: Sá Editora, 2011. 608p. ISBN 978-85-88193-62-8

- Standage, Tom (2006). A History of the World in 6 Glasses. New York, New York: Walker Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802715524.

- "Arkeologerna: Skatter i havet". UR Play. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- Blue p. 74

- Roueché, Berton. Alcohol in Human Culture. in: Lucia, Salvatore P. (Ed.) Alcohol and Civilization New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963 p. 178

- Blue p. 76

- Tannahill p. 295

- Tannahill p. 296

- Morison, Daniel, "The Doctor's Secret Journal," The Fort Mackinac Division Press, Lansing, Michigan, Copyright 1960

- Morison, Daniel, "The Doctor's Secret Journal," The Fort Mackinac Division Press, Lansing, Michigan, Copyright 1960, page 26.

- Frost, Doug (6 January 2005). "Rum makers distill unsavory history into fresh products". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Rorabaugh, W.J. (1981). The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. Oxford University Press. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0195029901.

- Buckner, Timothy Ryan (2005). "Constructing Identities on the Frontier of Slavery, Natchez Mississippi, 1760-1860" (PDF). p. 129. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- Pack p. 15

- Blue p. 77

- "Navy strength - a nautical history, section Proving the Proof". Sub 13 cocktail bar. 22 September 2017.

- Tannahill p. 273

- Pack p. 123

- Chapter 6 "Supplementary Income," para.0661 "Extra and other issues," Ministry of Defence regulations

- Blue p. 78

- Mikkelson, Barbara (9 May 2006). "Body found in barrel". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Snopes.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- Clarke p. 26

- Geoffrey Blainey The Tyranny of Distance: How Distance Shaped Australia's History Macmillan (1966)

- Clarke p. 29

- Koutsakis, George (6 June 2021). "Will Japanese whisky be eclipsed by Taiwan? The island's gin and rum also show promise – with one distillery promising spirits 'good enough for God'". www.scmp.com. South China Morning Post. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Blue p. 81-82

- "The drink that nearly knocked me out with one sniff" Archived 31 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine by Nick Davis, BBC News, 6 September 2015

- "At a temperance meeting recently held in New Zealand, an intemperate chief addressed the audience, to the surprise of all, in favor of banning rum from the country. Some rude-rum selling foreigners interrupted him with a sneer that he was the greatest drunkard in the region". From The Religious Monitor, or Evangelical Repository Vol. XIV Archived 1 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Hoffman & White, 1837-39, p. 480.

- Meara, Mallory (2021). Girly drinks: a world history of women and alcohol. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Hanover Square Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-335-28240-8. OCLC 1273729039.

- Selsky, Andrew (15 September 2003). "Age-old drink losing kick". The Miami Herald.

- "Tourism Industry in Liberia". Uniboa.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- "Surreptitious Drug Abuse and the New". Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- "Photo-article on Liberian village life". Pages.prodigy.net. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Sugarcane Machete". National Museum of American History. 2005.

- "Chapter 3 Sugar cane". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- "The Pirate Surgeon's Journal: Golden Age of Piracy: Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health, Page 10".

- Vaughan, Mark (1 June 1994). "Tropical Delights". Cigar Aficionado. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 7 June 2005.

- Cooper p. 54

- Nicol, Denis A. (2003). "Rum". In Lea, Andrew G.H.; Piggott, John R. (eds.). Fermented Beverage Production. Link.springer.com. Springer, Boston, MA. pp. 263–287. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0187-9_12. ISBN 978-0-306-47706-5.

- Branch, Legislative Services. "Consolidated Federal Laws of Canada, Food and Drug Regulations". laws.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- "Manufacturing Rum". Archived from the original on 20 November 2003. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- Curtiss, Wayne. "One Man's Quest to Make 20-Year-Old Rum in Just Six Days". Wired. No. 30 May 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Blue p. 80

- Cooper p. 54-55

Sources

- Blainey, Geoffrey (1966). The Tyranny of Distance: How Distance Shaped Australia's History. Sun Books, Australia. ISBN 978-0333338360.

- Blue, Anthony Dias (2004). The Complete Book of Spirits : A Guide to Their History, Production, and Enjoyment. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-054218-4.

- Curtis, Wayne (2006). And a bottle of rum - a history of the New World in ten cocktails. Crown Publishers. p. 285. ISBN 9781400051670.

- Clarke, Frank G. (2002). The History of Australia. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31498-8.

- Cooper, Rosalind (1982). Spirits & Liqueurs. HPBooks. ISBN 978-0-89586-194-8.

- Foley, Ray (2006). Bartending for Dummies: A reference for the Rest of Us. Wiley Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-05056-9.

- Pack, James (1982). Nelson's Blood: The Story of Naval Rum. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-944-3.

- Rorabaugh, W. J. (1981). The Alcoholic Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195029901.

- Tannahill, Reay (1973). Food in History. Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-1437-8.

Further reading

- Williams, Ian (2005). Rum: A Social and Sociable History of the Real Spirit of 1776. Nation Books. (extract)

- Broom, Dave (2003). Rum. Abbeville Press.

- Arkell, Julie (1999). Classic Rum. Prion Books.

- Coulombe, Charles A. (2004). Rum: The Epic Story of the Drink that Changed Conquered the World. Citadel Press.

- Smith, Frederick (2005). Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History. University Press of Florida. (Introduction)

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.