Apple Lisa

Lisa is a desktop computer developed by Apple, released on January 19, 1983. It is one of the first personal computers to present a graphical user interface (GUI) in a machine aimed at individual business users. Its development began in 1978.[2] It underwent many changes before shipping at US$9,995 (equivalent to $27,190 in 2021) with a five-megabyte hard drive. It was affected by its high price, insufficient software, unreliable Apple FileWare floppy disks, and the immediate release of the cheaper and faster Macintosh. Only 10,000 were sold in two years.

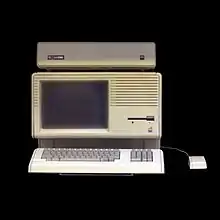

An Apple Lisa with dual 5.25" Twiggy floppy drives and 5 MB ProFile hard disk | |

| Also known as | Locally Integrated System Architecture |

|---|---|

| Developer | Apple Computer |

| Manufacturer | Apple Computer |

| Type | Personal computer |

| Release date | January 19, 1983 |

| Introductory price | US$9,995 (equivalent to $27,190 in 2021) |

| Discontinued | August 1, 1986 |

| Units sold | 10,000[1] |

| Operating system | Lisa OS, Xenix |

| CPU | Motorola 68000 @ 5 MHz |

| Memory | 1 MB RAM, 16 KB Boot ROM |

| Display | 12 in (30 cm) monochrome, 720 × 364 |

| Mass | 48 lb (22 kg) |

| Predecessor | Apple II Plus Apple III |

| Successor | Macintosh XL Macintosh |

Considered a commercial failure (albeit one with technical acclaim), Lisa introduced a number of advanced features that reappeared on the Macintosh and eventually IBM PC compatibles. Among them is an operating system with protected memory[3] and a document-oriented workflow. The hardware was more advanced overall than the forthcoming Macintosh 128K; the Lisa included hard disk drive support, capacity for up to 2 megabytes (MB) of random-access memory (RAM), expansion slots, and a larger, higher-resolution display.

The complexity of the Lisa operating system and its associated programs (most notably its office suite), as well as the ad hoc protected memory implementation (due to the lack of a Motorola MMU), placed a high demand on the CPU and, to some extent, the storage system. As a result of cost-cutting measures designed to bring it more into the consumer market, advanced software, and factors such as the delayed availability of the 68000 and its impact on the design process, Lisa's user experience feels sluggish overall. The workstation-tier price (albeit at the low end of the spectrum at the time) and lack of a technical software application library made it a difficult sell for much of the technical workstation market. Compounding matters, the runaway success of the IBM PC and Apple's decision to compete with itself, mainly via the lower-cost Macintosh, were further impediments to its acceptance.

In 1982, after Steve Jobs was forced out of the Lisa project by Apple's board of directors,[4] he appropriated the Macintosh project from Jef Raskin, who had originally conceived of a sub-$1,000 text-based appliance computer in 1979. Jobs immediately redefined Macintosh as a less expensive and more focused version of the graphical Lisa.

When Macintosh launched in January 1984, it quickly surpassed Lisa's sluggish sales. Jobs then began assimilating increasing numbers of Lisa staff, as he had done with the Apple II division after assuming control over Raskin's project. Newer Lisa models were eventually introduced to address its shortcomings but, even after lowering the list price considerably, the platform failed to achieve favorable sales numbers compared to the much less expensive Mac. The final model, the Lisa 2/10, was rebranded as the Macintosh XL to become the high-end model in the Macintosh series.[5]

History

Name

Though the documentation shipped with the original Lisa only refers to it as "The Lisa", Apple officially stated that the name was an acronym for "Locally Integrated Software Architecture" or "LISA".[6] Because Steve Jobs's first daughter was named Lisa Nicole Brennan (born in 1978), it was sometimes inferred that the name also had a personal association, and perhaps that the acronym was a backronym invented later to fit the name. Andy Hertzfeld[7] states the acronym was reverse engineered from the name "Lisa" in late 1982 by the Apple marketing team, after they had hired a marketing consultancy firm to come up with names to replace "Lisa" and "Macintosh" (at the time considered by Jef Raskin to be merely internal project codenames) and then rejected all of the suggestions. Privately, Hertzfeld and the other software developers used "Lisa: Invented Stupid Acronym", a recursive backronym, while computer industry pundits coined the term "Let's Invent Some Acronym" to fit the Lisa's name. Decades later, Jobs would tell his biographer Walter Isaacson: "Obviously it was named for my daughter."[8]

Research and design

The project began in 1978 as an effort to create a more modern version of the then-conventional design epitomized by the Apple II. A ten-person team occupied its first dedicated office, which was nicknamed "the Good Earth building" and located at 20863 Stevens Creek Boulevard next to the restaurant named Good Earth.[9] Initial team leader Ken Rothmuller was soon replaced by John Couch, under whose direction the project evolved into the "window-and-mouse-driven" form of its eventual release. Trip Hawkins and Jef Raskin contributed to this change in design.[10] Apple's cofounder Steve Jobs was involved in the concept.

At Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center, research had already been underway for several years to create a new humanized way to organize the computer screen, today known as the desktop metaphor. Steve Jobs visited Xerox PARC in 1979, and was absorbed and excited by the revolutionary mouse-driven GUI of the Xerox Alto. By late 1979, Jobs successfully negotiated a payment of Apple stock to Xerox, in exchange for his Lisa team receiving two demonstrations of ongoing research projects at Xerox PARC. When the Apple team saw the demonstration of the Alto computer, they were able to see in action the basic elements of what constituted a workable GUI. The Lisa team put a great deal of work into making the graphical interface a mainstream commercial product.

The Lisa was a major project at Apple, which reportedly spent more than $50 million on its development.[11] More than 90 people participated in the design, plus more in the sales and marketing effort, to launch the machine. BYTE credited Wayne Rosing with being the most important person on the development of the computer's hardware until the machine went into production, at which point he became technical lead for the entire Lisa project. The hardware development team was headed by Robert Paratore.[12] The industrial design, product design, and mechanical packaging were headed by Bill Dresselhaus, the Principal Product Designer of Lisa, with his team of internal product designers and contract product designers from the firm that eventually became IDEO. Bruce Daniels was in charge of applications development, and Larry Tesler was in charge of system software.[13] The user interface was designed in a six-month period, after which the hardware, operating system, and applications were all created in parallel.

In 1982, after Steve Jobs was forced out of the Lisa project,[14] he appropriated the existing Macintosh project, which Jef Raskin had conceived in 1979 and led to develop a text-based appliance computer. Jobs redefined Macintosh as a cheaper and more usable Lisa, leading the project in parallel and in secret, and substantially motivated to compete with the Lisa team.

In September 1981, below the announcement of the IBM PC, InfoWorld reported on Lisa, "McIntosh", and another Apple computer secretly under development "to be ready for release within a year". It described Lisa as having a 68000 and 128KB RAM, and "designed to compete with the new Xerox Star at a considerably lower price".[15] In May 1982, the magazine reported that "Apple's yet-to-be-announced Lisa 68000 network work station is also widely rumored to have a mouse."[16]

Launch

Lisa's low sales were quickly surpassed by the January 1984 launch of the Macintosh. Newer versions of the Lisa were introduced that addressed its faults and lowered its price considerably, but it failed to achieve favorable sales compared to the much less expensive Mac. The Macintosh project assimilated a lot more Lisa staff. The final revision of the Lisa, the Lisa 2/10, was modified and sold as the Macintosh XL.[5]

Discontinuation

The high cost and the delays in its release date contributed to the Lisa's discontinuation although it was repackaged and sold at $4,995, as the Lisa 2. In 1986, the entire Lisa platform was discontinued.

In 1987, Sun Remarketing purchased about 5,000 Macintosh XLs and upgraded them. In 1989, with the help of Sun Remarketing, Apple disposed of approximately 2,700 unsold Lisas in a guarded landfill in Logan, Utah, in order to receive a tax write-off on the unsold inventory.[17] Some leftover Lisa computers and spare parts were available until Cherokee Data (who purchased Sun Remarketing) went out of business.

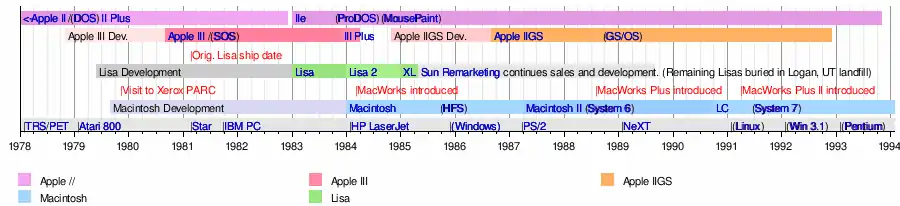

Timeline of Lisa models

Overview

Hardware

The Lisa was first introduced on January 19, 1983. It is one of the first personal computer systems with a graphical user interface (GUI) to be sold commercially. It uses a Motorola 68000 CPU clocked at 5 MHz and has 1 MB of RAM. It can be upgraded to 2 MB and later shipped with as little as 512 kilobytes. The CPU speed and model was not changed from the release of the Lisa 1 to the repackaging of the hardware as Macintosh XL.

The real-time clock uses a 4-bit integer and the base year is defined as 1980; the software won't accept any value below 1981, so the only valid range is 1981–1995.[18] The real-time clock depends on a 4 x AA-cell NiCd pack of batteries that only lasts for a few hours when main power is not present. Prone to failure over time, the battery packs could leak corrosive alkaline electrolyte and ruin the circuit boards.[18]

The integrated monochrome black-on-white monitor has 720 × 364 rectangular pixels on a 12-inch (30 cm) screen.

Among the printers supported by Lisa are the Apple Dot Matrix Printer, Apple Daisy Wheel Printer, the Apple ImageWriter dot matrix, and a Canon inkjet printer. Inkjet printing was quite new at the time. Despite having a monochromatic monitor, Apple enabled software to support some color printing, due to the existence of the Canon printer.

CPU

The use of the slowest-clocked version of Motorola's 68000 was a cost-cutting measure, as the 68000 was initially expensive. By the time the price had come down, Apple had already designed the Lisa software around the timing of the 5 MHz processor. Lisa had been in development for such a long time that it was not initially developed for the 68000 and much of its development was done on a pre-chip form of the 68000, which was much slower than the shipping CPU. Lisa software was primarily coded in Pascal to save development time, given the high complexity of the software.

The sophistication of the Lisa software (which included a multitasking GUI requiring a hard disk), coupled with the slow speed of the CPU, RAM, lack of hardware graphics acceleration coprocessor, and protected memory implementation, led to the impression that the Lisa system was very slow. However, a productivity study done in 1984 rated the Lisa above the IBM PC and Macintosh, perhaps countering the high degree of focus on UI snappiness and other factors in perceived speed rather than actual productivity speed.

RAM

Lisa was designed to use slower (albeit more reliable) parity memory, and other features that reduced speed but increased stability and value. Lisa is able to operate when RAM chips failed on its memory boards, unlike later Macintosh systems, reducing the cost to owners by enabling the usage of partially-failed boards. The Lisa system isolates the failed chip or chips and uses the rest of the board's RAM. This was particularly important given the large number of individual RAM chips Lisa used in 1983 for a consumer system (at around $2,500 in cost to Apple per machine). RAM could be upgraded to 2 MB.

Drives

The original Lisa, later called the Lisa 1, has two Apple FileWare 5.25-inch double-sided variable-speed floppy disk drives, more commonly known by Apple's internal code name for the drive, "Twiggy".[19] They had, for the time, a very high capacity of approximately 871 kB each, but proved to be unreliable[20] and required nonstandard diskettes. Competing systems implementing that level of per-diskette data storage had to utilize much larger 8" floppy disks. These disks were seen as cumbersome and old-fashioned for a consumer system. Apple had worked hard to increase the storage capacity of the minifloppy-size disk by pioneering features that Sony perfected shortly after with its microfloppy drives. Although it used a Twiggy drive in the prototype stage, the first Macintosh was launched the following year with one of the Sony 400 KB 3.5" "microfloppy" disk drives. 1984 also saw the release of the first revision of Lisa, the Lisa 2, which also included a single Sony drive. Apple provided free upgrades for Lisa 1 owners to Lisa 2 hardware, including the replacement of the Twiggy drives with a single Sony drive. The Sony drive, being only single-sided, could not store nearly as much data as a single Twiggy, but did so with greater reliability. The IBM PC shipped with a minifloppy (5.25-inch) drive that stored even less data: 360 KB. It was also slower and did not have the protective shell of the Sony microfloppy drive diskettes, which improves reliability.

An optional external 5 MB or, later, a 10 MB Apple ProFile hard drive (originally designed and produced for the Apple III by a third party), was available. With the introduction of the Lisa 2/10, an optional 10 MB compact internal proprietary hard disk manufactured by Apple, known as the "Widget", was also offered. As with the Twiggy, the Widget developed a reputation for reliability problems. The ProFile, by contrast, was typically long-lived. The Widget was incompatible with earlier Lisa models.

In an effort to increase the reliability of the machine, Apple included, starting with Lisa 1, several mechanisms involved with disk storage that were innovative and not present on at least the early releases of the Macintosh, nor on the IBM PC. For example, block sparing was implemented, which would set aside bad blocks, even on floppy disks.[21] Another feature was the redundant storage of critical operating system information, for recovery in case of corruption.

Lisa 2

The first hardware revision, the Lisa 2, was released in January 1984 and was priced between US$3,495 and $5,495.[5][22] It was much less expensive than the original model and dropped the Twiggy floppy drives in favor of a single 400K Sony microfloppy.[23] The Lisa 2 has as little as 512 KB of RAM. The Lisa 2/5 consists of a Lisa 2 bundled with an external 5- or 10-megabyte hard drive.[24] In 1984, at the same time the Macintosh was officially announced, Apple offered free upgrades to the Lisa 2/5 to all Lisa 1 owners, by swapping the pair of Twiggy drives for a single 3.5-inch drive,[23] and updating the boot ROM and I/O ROM. In addition, the Lisa 2's new front faceplate accommodates the reconfigured floppy disk drive, and it includes the new inlaid Apple logo and the first Snow White design language elements. The Lisa 2/10 has a 10MB internal hard drive (but no external parallel port) and a standard configuration of 1 MB of RAM.[24]

Developing early Macintosh software required a Lisa 2.[25] There were relatively few third-party hardware offerings for the Lisa, as compared to the earlier Apple II. AST offered a 1.5 MB memory board, which – when combined with the standard Apple 512 KB memory board – expands the Lisa to a total of 2 MB of memory, the maximum amount that the MMU can address.

Late in the product life of the Lisa, there were third-party hard disk drives, SCSI controllers, and double-sided 3.5-inch floppy-disk upgrades. Unlike the original Macintosh, the Lisa has expansion slots. The Lisa 2 motherboard has a very basic backplane with virtually no electronic components, but plenty of edge connector sockets and slots. There are two RAM slots, one CPU upgrade slot, and one I/O slot, all in parallel placement to each other. At the other end, there are three "Lisa" slots in parallel.

Macintosh XL

In January 1985, following the Macintosh, the Lisa 2/10 (with integrated 10 MB hard drive) was rebranded as Macintosh XL. It was given a hardware and software kit, enabling it to reboot into Macintosh mode and positioning it as Apple's high-end Macintosh. The price was lowered yet again (to $4,000) and sales tripled, but CEO John Sculley said that Apple would have lost money increasing production to meet the new demand.[26] Apple discontinued the Macintosh XL, leaving an eight-month void in Apple's high-end product line until the Macintosh Plus was introduced in 1986. The report that many Lisa machines were never sold and were disposed of by Apple is particularly interesting in light of Sculley's decision concerning the increased demand.

Software

Lisa OS

The Lisa operating system features protected memory,[27] enabled by a crude hardware circuit compared to the Sun-1 workstation (c. 1982), which features a full memory management unit. Motorola did not have an MMU (memory-management unit) for the 68000 ready in time, so third parties such as Apple had to come up with their own solutions. Despite the sluggishness of Apple's solution, which was also the result of a cost-cutting compromise, the Lisa system differed from the Macintosh system which would not gain protected memory until Mac OS X, released eighteen years later. (Motorola's initial MMU also was disliked for its high cost and slow performance.) Based, in part, on elements from the Apple III SOS operating system released three years earlier, the Lisa's disk operating system also organizes its files in hierarchical directories, as do UNIX workstations of the time which were the main competition to Lisa in terms of price and hardware. Filesystem directories correspond to GUI folders, as with previous Xerox PARC computers from which the Lisa borrowed heavily. Unlike the first Macintosh, whose operating system could not utilize a hard disk in its first versions, the Lisa system was designed around a hard disk being present.

Conceptually, the Lisa resembles the Xerox Star in the sense that it was envisioned as an office computing system. It also resembles Microsoft Office from a software standpoint, in that its software is designed to be an integrated "office suite". The Lisa's office software suite shipped long before the existence of Microsoft Office, although some of the constituent components differ (e.g. Lisa shipped with no presentation package and Office shipped without a project management package). Consequently, Lisa has two main user modes: the Lisa Office System and the Workshop. The Lisa Office System is the GUI environment for end users. The Workshop is a program development environment and is almost entirely text-based, though it uses a GUI text editor. The Lisa Office System was eventually renamed "7/7", in reference to the seven supplied application programs: LisaWrite, LisaCalc, LisaDraw, LisaGraph, LisaProject, LisaList, and LisaTerminal.

Apple's warranty said that this software works precisely as stated, and Apple refunded an unspecified number of users, in full, for their systems. These operating system frailties, and costly recalls, combined with the very high price point, led to the failure of the Lisa in the marketplace. NASA purchased Lisa machines, mainly to use the LisaProject program.

In 2018, the Computer History Museum announced it would be releasing the source code for Lisa OS, following a check by Apple to ensure this would not impact other intellectual property. For copyright reasons, this release did not include the American Heritage dictionary.[28]

Task-oriented workflow

With Lisa, Apple presented users with what is generally, but imprecisely, known as a document-oriented paradigm. This is contrasted with program-centric design. The user focuses more on the task to be accomplished than on the tool used to accomplish it. Apple presents tasks, with Lisa, in the form of stationery. Rather than opening LisaWrite, for instance, to begin to do word processing, users initially "tear off stationery", visually, that represents the task of word processing. Either that, or they open an existing LisaWrite document that resembles that stationery. By contrast, the Macintosh and most other GUI systems focus primarily on the program that is used to accomplish a task — directing users to that first.

One benefit of task-based computing is that users have less of a need to memorize which program is associated with a particular task. That problem is compounded by the contemporary practice of naming programs with very nonintuitive names such as Chrome and Safari. A drawback of task-oriented design, when presented in document-oriented form, is that the naturalness of the process can be lacking. The most frequently cited example with Lisa is the use of LisaTerminal, in which a person tears off "terminal stationery" — a broken metaphor. However, task-based design does not necessarily require characterizing everything as a document, or as stationery specifically.

More recently, menus and tabs have been used, rather sparingly, to present more task-based workflows. A "power user" could have somewhat laboriously customized the Apple menu in many versions of Mac OS (prior to Mac OS X) to contain folders that are task-oriented. Tab systems are typically add-ons for contemporary operating systems and can be organized in a task-based manner — such as having a "web browsing" tab that contains various web browser programs. Task-oriented presentation is very helpful for systems that have many programs and a variety of users, such as a language-learning computer lab that caters to those learning a variety of languages. It is also helpful for computer users who have not yet memorized what program name, however unintuitive, is associated with a task. Some Linux desktop systems combine some unintuitive program names (e.g. Amarok) with task-based organization (menus that organize programs by task) — in the desire to make utilizing Linux desktop systems less of a challenge for those switching from the dominant desktop platforms.

The desire for emotional marketing reinforcement appears to be a strong factor in the choice, by most companies, to promote the program-centric paradigm. Otherwise, there would be little incentive to give programs obscure unintuitive names and/or to add company names to the program name (e.g. Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, etc.). Combining unintuitive names with company names is especially popular today (e.g. Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox). This is the opposite goal of the Lisa paradigm where the brand name and the program name are intentionally made more invisible to the user.

Internationalization

Within a few months of the Lisa's introduction in the US, fully translated versions of the software and documentation were commercially available for the British, French, West German, Italian, and Spanish markets, followed by several Scandinavian versions shortly thereafter. The user interface for the OS, all seven applications, LisaGuide, and the Lisa diagnostics (in ROM) can be fully translated, without any programming required, using resource files and a translation kit. The keyboard can identify its native language layout, and the entire user experience will be in that language, including any hardware diagnostic messages.

Although several non-English keyboard layouts are available, the Dvorak keyboard layout was never ported to the Lisa, though such porting had been available for the Apple III, IIe, and IIc, and was later done for the Macintosh. Keyboard-mapping on the Lisa is complex and requires building a new OS. All kernels contain images for all layouts, so due to serious memory constraints, keyboard layouts are stored as differences from a set of standard layouts; thus only a few bytes are needed to accommodate most additional layouts. An exception is the Dvorak layout that moves just about every key and thus requires hundreds of extra bytes of precious kernel storage regardless of whether it is needed.

Each localized version (built on a globalized core) requires grammatical, linguistic, and cultural adaptations throughout the user interface, including formats for dates, numbers, times, currencies, sorting, even for word and phrase order in alerts and dialog boxes. A kit was provided, and the translation work was done by native-speaking Apple marketing staff in each country. This localization effort resulted in about as many Lisa unit sales outside the US as inside the US over the product's lifespan, while setting new standards for future localized software products, and for global project coordination.

MacWorks

In April 1984, following the release of the Macintosh, Apple introduced MacWorks, a software emulation environment which allows the Lisa to run Macintosh System software and applications.[29] MacWorks helped make the Lisa more attractive to potential customers, although it did not enable the Macintosh emulation to access the hard disk until September. Initial versions of the Mac OS could not support a hard disk on the Macintosh machines. In January 1985, re-branded MacWorks XL, it became the primary system application designed to turn the Lisa into the Macintosh XL.

Third-party software

A significant impediment to third-party software on the Lisa was the fact that, when first launched, the Lisa Office System could not be used to write programs for itself. A separate development OS, called Lisa Workshop, was required. During this development process, engineers would alternate between the two OSes at startup, writing and compiling code on one OS and testing it on the other. Later, the same Lisa Workshop was used to develop software for the Macintosh. After a few years, a Macintosh-native development system was developed. For most of its lifetime, the Lisa never went beyond the original seven applications that Apple had deemed enough to "do everything", although UniPress Software did offer UNIX System III for $495.[30]

The company known as the Santa Cruz Operation (SCO) offered Microsoft XENIX (version 3), a UNIX-like command-line operating system, for the Lisa 2 — and the Multiplan spreadsheet (version 2.1) that ran on it.[31]

Reception

.jpg.webp)

BYTE wrote in February 1983 after previewing the Lisa that it was "the most important development in computers in the last five years, easily outpacing [the IBM PC]". It acknowledged that the $9,995 price was high, and concluded "Apple ... is not unaware that most people would be incredibly interested in a similar but less expensive machine. We'll see what happens".[11]

The Apple Lisa was a commercial failure for Apple, the largest since the failure of the Apple III of 1980. Apple sold approximately 10,000[1] Lisa machines at a price of US$9,995 (equivalent to about $27,200 in 2021),[32] generating total sales of $100 million against a development cost of more than $150 million.[1]

The high price put the Lisa at the bottom of the price realm of technical workstations, but without much of a technical application library. Some features that some much more expensive competing systems included were such things as hardware graphics coprocessors (which increased perceived system power by improving GUI snappiness) and higher-resolution portrait displays. Lisa's implementation of the requisite graphical interface paradigm was novel but many of the time associated UI snappiness with power, even if that was so simplistic as to miss the mark, in terms of overall productivity. The mouse, for example, was dismissed by many critics of the time as being a toy, and mouse-driven machines as being unserious. Of course, the mouse would go on to displace the pure-CLI design for the vast majority of users. The largest Lisa customer was NASA, which used LisaProject for project management.[33] Lisa was not slowed purely by having a 5 MHz CPU (the lowest clock offered by Motorola), sophisticated parity RAM, a slow hard disk interface (for the ProFile), and the lack of a graphics coprocessor (which would have increased cost). It also had its software mainly coded in Pascal, was designed to multitask, and had advanced features like the clipboard for pasting data between programs. This sophistication came at the price of snappiness although it added to productivity. The OS even had "soft power", remembering what was open and where desktop items were positioned. Many such features are taken for granted today but were not available on typical consumer systems.

The massive brand power of IBM at that time was the largest factor in the PC's eventual dominance. Computing critics complained about the relatively primitive hardware ("off-the-shelf components") of the PC but admitted that it would be a success simply due to IBM's mindshare. By the time Lisa was available in the market, the less-expensive and less-powerful IBM PC had already become entrenched. The x86 platform's backward compatibility with the CP/M operating system was helpful for the PC, given that many existing business software applications were originally written for CP/M. Apple had attempted to compete with the PC, via the Apple II platform. DOS was very primitive when compared with the Lisa OS, but the CLI was familiar territory for most users of the time. It would be years before Microsoft would offer an integrated office suite.

The 1984 release of the Macintosh further eroded the Lisa's marketability, as the public perceived that Apple was abandoning it in favor of the Macintosh. Any marketing of the Macintosh clashed with promotion of the Lisa, since Apple had not made the platforms compatible. Macintosh was superficially faster (mainly in terms of UI responsiveness) than Lisa but much more primitive in other key aspects, such as the lack of protected memory (which led to the famous bomb and completely frozen machines for so many years), very small amount of non-upgradable RAM, no ability to use a hard disk (which led to heavy criticism about frequent disk-swapping), no sophisticated file system, a smaller display (with lower resolution), lack of numeric keypad, lack of a built-in screensaver, inability to multitask, lack of parity RAM, lack of expansion slots, lack of a calculator with a paper tape and RPN, more primitive office software, and more. The Macintosh beat the Lisa in terms of having sound support (Lisa had only a beep), having square pixels (which reduced perceived resolution but removed the problem of display artifacts), having a nearly 8 MHz CPU, having more resources placed into marketing (leading to a large increase in the system's price tag), and being coded primarily in assembly. Some features, like protected memory, remained absent from the Macintosh platform for eighteen years, when Mac OS X was released for the desktop. The Lisa was also designed to readily support multiple operating systems, making booting between them intuitive and convenient — something that has taken a very long time to achieve since Lisa, at least as a standard desktop OS feature.

The Lisa 2 and its Mac ROM-enabled sibling the Macintosh XL are the final two releases in the Lisa line, which was discontinued in April 1985.[34] The Macintosh XL is a hardware and software conversion kit to effectively reboot Lisa into Macintosh mode. In 1986, Apple offered all Lisa and XL owners the opportunity to return their computer, with an additional payment of US$1,498, in exchange for a Macintosh Plus and Hard Disk 20.[35] Reportedly, 2,700 working but unsold Lisa computers were buried in a landfill.[36]

Legacy

The Macintosh project, led by Steve Jobs, borrowed heavily from Lisa's GUI paradigm and directly took many of its staff, to create Apple's flagship platform of the next several decades. The column-based interface, for instance, utilized by Mac OS X, had originally been developed for Lisa. It had been discarded in favor of the icon view.

Apple's culture of object-oriented programming on Lisa contributed to the 1988 conception of Pink, the first attempt to rearchitect the operating system of Macintosh.

See also

- Macintosh 128K

- People:

- Bill Atkinson

- Rich Page

- Brad Silverberg

- Technology:

- History of the graphical user interface

- Cut, copy, and paste

- Xerox Star

- Visi On

- Apple ProFile

- GEMDOS (adaptation for Lisa 2/5)

References

- O'Grady, Jason D. (2009). Apple Inc. ABC-CLIO. p. 72. ISBN 9780313362446.

By most accounts, Lisa was a failure, selling only 10,000 units. It reportedly cost Apple more than $150 million to develop Lisa ($100 million in software, $50 million in hardware), and it only brought in $100 million in sales for a net $50-million loss.

- Christoph Dernbach (October 12, 2007). "Apple Lisa". Mac History. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- Lisa Operating System Reference Manual. p. 34.

- Simon, Jeffrey S.; Young, William L. (April 14, 2006). iCon : Steve Jobs, the greatest second act in the history of business (Newly updated. ed.). Hoboken, NJ. ISBN 978-0471787846. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Linzmayer, Owen W. (2004). Apple confidential 2.0 : the definitive history of the world's most colorful company (2nd ed.). San Francisco, Calif. p. 79. ISBN 978-1593270100. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- O'Grady, Jason D. (2009). Apple Inc. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0313362446. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Andy Hertzfeld (2005). "Bicycle". Revolution in the Valley. O'Reilly. p. 36. ISBN 0-596-00719-1.

- Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs. Simon & Schuster. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- Hertzfeld, Andy (October 1980). "Good Earth". Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Hormby, Tom (October 5, 2005). "History of Apple's Lisa". Low End Mac. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008.

- Williams, Gregg (February 1983). "The Lisa Computer System". BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 2. pp. 33–50. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- "Robert Paratore".

- Morgan, Chris; Williams, Gregg; Lemmons, Phil (February 1983). "An Interview with Wayne Rosing, Bruce Daniels, and Larry Tesler". BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 2. pp. 90–114. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Simon & Young 2006.

- Freiberger, Paul (September 14, 1981). "Apple Develops New Computers". InfoWorld. Vol. 3, no. 18. pp. 1, 14. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Markoff, John (May 10, 1982). "Computer mice are scurrying out of R&D labs". InfoWorld. Vol. 4, no. 18. pp. 10–11. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- McCollum, Charles (October 16, 2011). "Editor's Corner: Logan has interesting link to Apple computer history". The Herald Journal. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "The little-known Apple Lisa: Five quirks and oddities". January 30, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- Linzmayer 2004, pp. 77–78

- Linzmayer 2004, p. 78

- Craig, David (February 16, 1993). "The Legacy of the Apple Lisa Personal Computer: An Outsider's View". Oberlin Computer Science. David T. Craig. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Mac GUI :: Re: MACINTOSH opinion and request". macgui.com.

- Mace, Scott (February 13, 1984). "Apple introduces Lisa 2; basic model to cost $3,500". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 7. pp. 65–66. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Pina, Larry (1990). Macintosh Repair & Upgrade Secrets (1st ed.). Carmel, IN, USA: Hayden Books. p. 236. ISBN 0672484528. LCCN 89-6375.

- da Cruz, Frank (June 11, 1984). "Macintosh Kermit No-Progress Report". Info-Kermit mailing list (Mailing list). Kermit Project, Columbia University. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- McGeever, Christine (June 3, 1985). "Apple's LISA meets a bad end". InfoWorld. Vol. 7, no. 22. pp. 21–22. ISSN 0199-6649. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- Lisa Operating System Reference Manual. p. 50.

- Ruggeri, Luca (January 17, 2018). "The Computer History Museum will open source Apple's Lisa OS". Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "The Lisa 2: Apple's ablest computer". BYTE. No. Dec 1984. pp. A106–A114. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006.

- "Unix Spoken Here / and MS-DOS, and VMS too!". BYTE (advertisement). Vol. 8, no. 12. December 1983. p. 334. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- Photograph of Lisa Xenix Multiplan diskette (JPEG) (Digital photography). Postimg.com. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "A Look Back at Apple Products of Old". Technologeek. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Isaacson 2011

- "Back in Time", A+ Magazine, Feb 1987: 48–49.

- "Signal 26, March 1986, circulation 45,013". www.semaphorecorp.com.

- Tiwari, Aditya (April 21, 2016). "Why Are 2700 Apple Lisa Computers Buried in a Landfill?".

External links

- Tech: Apple Lisa Demo (1984) on YouTube

- Using Apple' Lisa for Real Work

- Lisa 2/5 info.

- mprove: Graphical User Interface of Apple Lisa

- "Inventing the Lisa User Interface by Rod Perkins, Dan Keller and Frank Ludolph (1 MB PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2005. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- Apple Lisa Memorial Exhibition at Dongdaemun Design Plaza, Seoul, Korea on YouTube