Lord Chamberlain's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men was a company of actors, or a "playing company" (as it then would likely have been described), for which Shakespeare wrote during most of his career. Richard Burbage played most of the lead roles, including Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth. Formed at the end of a period of flux in the theatrical world of London, it had become, by 1603, one of the two leading companies of the city and was subsequently patronized by James I.

It was founded during the reign of Elizabeth I of England in 1594 under the patronage of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, then the Lord Chamberlain, who was in charge of court entertainments. After Carey's death on 23 July 1596, the company came under the patronage of his son, George Carey, 2nd Baron Hunsdon, for whom it was briefly known as Lord Hunsdon's Men. When George Carey in turn became Lord Chamberlain on 17 March 1597, it reverted to its previous name. The company became the King's Men in 1603 when King James ascended the throne and became the company's patron. The company held exclusive rights to perform Shakespeare's plays.

Playhouses

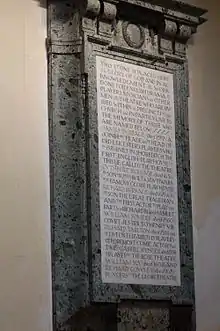

From 1594 the players performed at The Theatre, in Shoreditch. Problems with the landlord caused the company to move to the nearby Curtain Theatre in 1597. On the night of 29 December 1598, The Theatre was dismantled by the Burbage brothers, along with William Smith, their financial backer, Peter Street, a carpenter, and ten to twelve workmen. The beams were then carried south of the river to Southwark to form part of their new playhouse, the Globe Theatre. Built in 1599, this theatre was destroyed in a fire on 29 June 1613. The Globe was rebuilt by June 1614 and finally closed in 1642. The company also toured Britain, and visited France and Belgium.

A modern reconstruction of the original Globe, named "Shakespeare's Globe", was opened in 1997 near the site of the original theatre.

Personnel

The initial form of the Chamberlain's men arose largely from the departure of Edward Alleyn from Lord Strange's Men and the subsequent death of Lord Strange himself, in the spring of 1594. Yet the ultimate success of the company was largely determined by the Burbage family. James Burbage was the impresario who assembled the company and directed its activities until his death in 1597; his sons Richard and Cuthbert were members of the company, though Cuthbert did not act. This connection with the Burbages makes the Chamberlain's Men the central link in a chain that extends from the beginning of professional theatre (in 1574, James Burbage led the first group of actors to be protected under the 1572 statute against rogues and vagabonds) in Renaissance London to its end (in 1642, the King's Men were among the acting companies whose activities were ended by Parliament's prohibition of the stage.)

The Chamberlain's Men comprised a core of eight "sharers", who split profits and debts; perhaps an equal number of hired men who acted minor and doubled parts; and a slightly smaller number of boy players, who were sometimes bound apprentices to an adult actor. The original sharers in the Chamberlain's were eight. Probably the most famous in the 1590s to the 1600s was William Kempe, who had been in the company of the Earl of Leicester in the 1580s, and had later joined the King's Men. As the company's clown, he presumably took the broadest comic role in every play; he is identified with Peter in the quarto of Romeo and Juliet, and probably also originated Dog-berry in Much Ado About Nothing and Bottom in A Midsummer Night's Dream. Kempe has traditionally been viewed as the object of Hamlet's complaint about extemporising clowns; whether this association is right or wrong, Kempe had left the company by 1601. Another two sharers from Strange's Men had a long-standing association with Kempe. George Bryan had been in Leicester's Men in the 1580s, and at Elsinore with Kempe in 1586; because he is not mentioned in later Chamberlain's or King's Men documents, it is assumed that Bryan retired from the stage in 1597 or 1598. (Bryan lived on for some years; in the reign of James, he is listed as a Groom of the Chamber, with household duties, as late as 1613.) Thomas Pope, another Leicester's veteran, retired in 1600 and died in 1603. Both Bryan and Pope came to the company from Lord Strange's Men. Augustine Phillips also came from Strange's Men. He remained with the troupe until his death in 1605.

Two younger actors who came from Strange's, Henry Condell and John Heminges, are most famous now for collecting and editing the plays of Shakespeare's First Folio (1623). Both were relatively young in 1594, and both remained with the company until after the death of King James; their presence provided an element of continuity across decades of changing taste and commercial uncertainty.

(Some scholars have theorised that the company maintained its original eight-sharer structure, and that as any man left, through retirement or death, his place as sharer was filled by someone else. So, Bryan was replaced by William Sly, ca. 1597; Kempe was replaced by Robert Armin, ca. 1599; Pope was replaced by Condell, ca. 1600.[1] But this scheme, while possible, is not proven by the available evidence.)

The two sharers who would contribute the most to the Chamberlain's Men did not come from Strange's Men. Shakespeare's activities before 1594 have been a matter of considerable inquiry; he may have been with Pembroke's Men and Derby's Men in the early 1590s. As a sharer, he was at first equally important as actor and playwright. At an uncertain but probably early date, his writing became more important, although he continued to act at least until 1603, when he performed in Ben Jonson's Sejanus.

No less important was Richard Burbage. He was the lead actor of the Chamberlain's Men, who played Hamlet and Othello, and would go on to play King Lear and Macbeth in the new reign of King James, among many other roles. Though relatively little-known in 1594, he would become one of the most famous of Renaissance actors, achieving a fame and wealth exceeded only by Alleyn's.

Among the hired men were some who eventually became sharers. William Sly, who performed occasionally with the Admiral's Men during the 1590s, acted for the Chamberlain's by 1598, and perhaps before; he became a sharer after Phillips's death in 1605. Richard Cowley, identified as Verges by the quarto of Much Ado About Nothing, became a sharer in the King's Men. Nicholas Tooley, at one point apprenticed to Burbage, stayed with the company until his death in 1623. John Sincler (or Sincklo) may have specialised in playing thin characters; he seems to have remained a hired man. John Duke was a hired man who went to Worcester's Men early in James's reign.

At least two of the boys had distinguished careers. Alexander Cooke is associated with a number of Shakespeare's female characters, while Christopher Beeston went on to become a wealthy impresario in the seventeenth century.

Later sharers

The core members of the company changed in both major and minor ways before James's accession. The most famous change is that of Will Kemp, the circumstances of which remain unclear. Kempe was among the stakeholders in the Globe property, and he may have performed in that theatre in its first year. His famous morris dance to Norwich took place during Lent, when the company lay idle; not until the hastily added epilogue to Nine Days' Wonder (his account of the stunt) does he refer to his plan to return to individual performances. He may have had a hand in the bad quartos of Hamlet and The London Prodigal, in which the clown parts are unusually accurate.

Whatever the reason for his departure, Kempe was replaced by Robert Armin, formerly of Chandos's Men and an author in his own right. Small and fanciful, Armin offered significantly different options for Shakespeare, and the change is seen in the last Elizabethan and first Jacobean plays. Armin is generally credited with originating such characters as Feste in Twelfth Night, Touchstone in As You Like It, and the fool in King Lear.

Thus, by 1603 the core of the troupe was in some respects younger than it had been in 1594. Bryan, Pope, and Kempe, veterans of the 1580s, had left, and the remaining sharers (with the probable exception of Phillips), were roughly within a decade of 40.

Repertory and performances

Shakespeare's work undoubtedly formed the great bulk of the company's repertory. In their first year of performance, they may have staged such of Shakespeare's older plays as remained in the author's possession, including Henry VI, Part 2, Henry VI, Part 3, as well as Titus Andronicus. A Midsummer Night's Dream may have been the first play Shakespeare wrote for the new company; it was followed over the next two years by a concentrated burst of creativity that resulted in Romeo and Juliet, Love's Labours Lost, The Merchant of Venice, and the plays in the so-called second tetralogy. The extent and nature of the non-Shakespearean repertory in the first is not known; plays such as Locrine, The Troublesome Reign of King John, and Christopher Marlowe's Edward II have somewhat cautiously been advanced as likely candidates. The earliest non-Shakespearean play known to have been performed by the company is Ben Jonson's Every Man in His Humour, which was produced in the middle of 1598; they also staged the thematic sequel, Every Man Out of His Humour, the next year.

On the strength of these plays, the company quickly rivalled Alleyn's troupe for preeminence in London; as early as 1595 they gave four performances at court, followed by six the next year and four in 1597. These years were, typically for an Elizabethan company, also fraught with uncertainty. The company suffered along with the others in the summer of 1597, when the uproar over The Isle of Dogs temporarily closed the theatres; records from Dover and Bristol indicate that at least some of the company toured that summer. The character of Falstaff, though immensely popular from the start, aroused the ire of Lord Cobham, who objected to the use of the character's original name (Oldcastle), which derived from a member of Cobham's family.

In the last years of the century, the company continued to stage Shakespeare's new plays, including Julius Caesar and Henry V, which may have opened the Globe, and Hamlet, which may well have appeared first at the Curtain. Among non-Shakespearean drama, A Warning for Fair Women was certainly performed, as was the Tudor history Thomas Lord Cromwell, sometimes seen as a salvo in a theatrical feud with the Admiral's Men, whose lost plays on Wolsey date from the same year.

In 1601, in addition to their tangential involvement with the Essex rebellion, the company played a role in a less serious conflict, the so-called War of the Theatres. They produced Thomas Dekker's Satiromastix, a satire on Ben Jonson that seems to have ended the dispute. Somewhat uncharacteristically, Jonson does not appear to have held a grudge against the company; in 1603, they staged his Sejanus, with dissatisfying results. They also performed The London Prodigal, The Merry Devil of Edmonton, and The Fair Maid of Bristow, the last a rarity in that it is a Chamberlain's play that has never been attributed in any part to Shakespeare.

Controversies

The Lord Chamberlain's Men, and its individual members, largely avoided the scandals and turbulence in which other companies and actors sometimes involved themselves. Their most serious difficulty with the government came about as a result of their tangential involvement in the February 1601 insurrection of the Earl of Essex. Some of Essex's supporters had commissioned a special performance of Shakespeare's Richard II in the hope that the spectacle of that king's overthrow might make the public more amenable to the overthrow of Elizabeth (who later remarked, "I am Richard II, know ye not that?"). Augustine Phillips was deposed on the matter by the investigating authorities; he testified that the actors had been offered 40 shillings more than their usual fee, and for that reason alone had performed the play on 7 February, the day before Essex's uprising.[2] The explanation was accepted; the company and its members went unpunished, and even performed for Elizabeth at Whitehall on 24 February, the day before Essex's execution.

The following year, 1602, saw Christopher Beeston's rape charge. Probably some of the Lord Chamberlain's Men were among the actors who accompanied Beeston to his pretrial hearing at Bridewell and caused a disturbance there; but little can be said for certain.[3]

Audience

Theatre-going became an extremely popular activity for many in London in the late 16th and early 17th century because of the constant advertisement seen throughout London playbills. During these years London had a population of approximately 200,000. Within that group of 200,000 over 15,000 men and women attended plays on a weekly basis. The Londoners who attended the theatre also enjoyed cock-fighting, bull-baiting, and bear-baiting.[4] The theatres were in a rough part of London and were surrounded by the vices of drinking, gambling, and prostitution.[5]

As Lord Chamberlain’s Men popularity grew, they began to attract more and more theatre goers and became one of the most popular playing companies. But as their popularity grew so did the demand. The audience’s lives were ever changing which led to Lord Chamberlain’s Men having to cater to their audience resulting in the group having to perform six different plays every week. This was extremely strenuous on the actors as they had to memorize lines from many different plays and were given very little time if any for rehearsal.[6]

As Lord Chamberlain’s Men continued to prosper, they began to perform at larger venues. In 1599 they began playing at the outdoor Globe Theatre that had a capacity of 3,000 people and in 1609 they began performing at the indoor Blackfriars Theatre that had a capacity limit of 600. The minimum entry price at the Blackfriars was sixpence, six times that of the Globe, with better seats charged at eighteen and thirty pence.[7] This allowed the company to make money year-round from being able to have productions at indoor and outdoor theatres.[8]

Notes

- Halliday, Shakespeare Companion, pp. 90–91.

- Bate, Jonathan (2008). Soul of the Age. London: Penguin. pp. 256–86. ISBN 978-0-670-91482-1.

- Duncan Salkeld, "Literary Traces in Bridewell and Bethlem, 1602–1624," Review of English Studies, Vol. 56 No. 225, pp. 279–85.

- Höffle, Andreas (2001). Grabes, Herbert (ed.). Literary history - cultural history force fields and tensions. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. p. 165. ISBN 9783823341710.

- Cain, William E. "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction: Shakespeare at 400." Society, vol. 53, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 76-87.

- Cain, William E. "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction: Shakespeare at 400." Society, vol. 53, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 76-87.

- Dustagheer, Sarah (2017). Shakespeare's Two Playhouses: Repertory and Theatre Space at the Globe and the Blackfriars, 1599–1613. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781107190160.

- Cain, William E. "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction: Shakespeare at 400." Society, vol. 53, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 76-87.

References

- Adams, J. Q. Shakespearean Playhouses: A History of English Playhouses from the Beginnings to the Restoration. Boston, Mass.: Houghton-Mifflin, 1917.

- Baldwin, T.W. The Organization and Personnel of Shakespeare's Company. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1927.

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. Four Volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Cook, Ann Jennalie. The Privileged Playgoers of Shakespeare's London, 1576–1642. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Greg, W. W. Dramatic Documents from the Elizabethan Playhouses. Two volumes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931.

- Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage, 1574–1642. 3rd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964.

- Nunzeger, Edwin. A Dictionary of Actors and of Other Persons Associated With the Public Presentation of Plays in England Before 1642. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1929.

.png.webp)