Mach number

Mach number (M or Ma) (/mɑːk/; Czech: [max]) is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a boundary to the local speed of sound.[1][2] It is named after the Moravian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach.

.jpg.webp)

where:

- M is the local Mach number,

- u is the local flow velocity with respect to the boundaries (either internal, such as an object immersed in the flow, or external, like a channel), and

- c is the speed of sound in the medium, which in air varies with the square root of the thermodynamic temperature.

By definition, at Mach 1, the local flow velocity u is equal to the speed of sound. At Mach 0.65, u is 65% of the speed of sound (subsonic), and, at Mach 1.35, u is 35% faster than the speed of sound (supersonic). Pilots of high-altitude aerospace vehicles use flight Mach number to express a vehicle's true airspeed, but the flow field around a vehicle varies in three dimensions, with corresponding variations in local Mach number.

The local speed of sound, and hence the Mach number, depends on the temperature of the surrounding gas. The Mach number is primarily used to determine the approximation with which a flow can be treated as an incompressible flow. The medium can be a gas or a liquid. The boundary can be traveling in the medium, or it can be stationary while the medium flows along it, or they can both be moving, with different velocities: what matters is their relative velocity with respect to each other. The boundary can be the boundary of an object immersed in the medium, or of a channel such as a nozzle, diffuser or wind tunnel channeling the medium. As the Mach number is defined as the ratio of two speeds, it is a dimensionless number. If M < 0.2–0.3 and the flow is quasi-steady and isothermal, compressibility effects will be small and simplified incompressible flow equations can be used.[1][2]

Etymology

The Mach number is named after Moravian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach,[3] and is a designation proposed by aeronautical engineer Jakob Ackeret in 1929.[4] As the Mach number is a dimensionless quantity rather than a unit of measure, the number comes after the unit; the second Mach number is Mach 2 instead of 2 Mach (or Machs). This is somewhat reminiscent of the early modern ocean sounding unit mark (a synonym for fathom), which was also unit-first, and may have influenced the use of the term Mach. In the decade preceding faster-than-sound human flight, aeronautical engineers referred to the speed of sound as Mach's number, never Mach 1.[5]

Overview

Mach number is a measure of the compressibility characteristics of fluid flow: the fluid (air) behaves under the influence of compressibility in a similar manner at a given Mach number, regardless of other variables.[6] As modeled in the International Standard Atmosphere, dry air at mean sea level, standard temperature of 15 °C (59 °F), the speed of sound is 340.3 meters per second (1,116.5 ft/s; 761.23 mph; 661.49 kn).[7] The speed of sound is not a constant; in a gas, it increases proportionally to the square root of the absolute temperature, and since atmospheric temperature generally decreases with increasing altitude between sea level and 11,000 meters (36,089 ft), the speed of sound also decreases. For example, the standard atmosphere model lapses temperature to −56.5 °C (−69.7 °F) at 11,000 meters (36,089 ft) altitude, with a corresponding speed of sound (Mach 1) of 295.0 meters per second (967.8 ft/s; 659.9 mph; 573.4 kn), 86.7% of the sea level value.

Appearance in the continuity equation

As a measure of flow compressibility, the Mach number can be derived from an appropriate scaling of the continuity equation.[8] The full continuity equation for a general fluid flow is:

where is the material derivative, is the density, and is the flow velocity. For isentropic pressure-induced density changes, where is the speed of sound. Then the continuity equation may be slightly modified to account for this relation:

The next step is to nondimensionalize the variables as such:

where is the characteristic length scale, is the characteristic velocity scale, is the reference pressure, and is the reference density. Then the nondimensionalized form of the continuity equation may be written as:

where the Mach number . In the limit that , the continuity equation reduces to - this is the standard requirement for incompressible flow.

Classification of Mach regimes

While the terms subsonic and supersonic, in the purest sense, refer to speeds below and above the local speed of sound respectively, aerodynamicists often use the same terms to talk about particular ranges of Mach values. This occurs because of the presence of a transonic regime around flight (free stream) M = 1 where approximations of the Navier-Stokes equations used for subsonic design no longer apply; the simplest explanation is that the flow around an airframe locally begins to exceed M = 1 even though the free stream Mach number is below this value.

Meanwhile, the supersonic regime is usually used to talk about the set of Mach numbers for which linearised theory may be used, where for example the (air) flow is not chemically reacting, and where heat-transfer between air and vehicle may be reasonably neglected in calculations.

In the following table, the regimes or ranges of Mach values are referred to, and not the pure meanings of the words subsonic and supersonic.

Generally, NASA defines high hypersonic as any Mach number from 10 to 25, and re-entry speeds as anything greater than Mach 25. Aircraft operating in this regime include the Space Shuttle and various space planes in development.

| Regime | Flight speed | General plane characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mach) | (knots) | (mph) | (km/h) | (m/s) | ||

| Subsonic | <0.8 | <530 | <609 | <980 | <273 | Most often propeller-driven and commercial turbofan aircraft with high aspect-ratio (slender) wings, and rounded features like the nose and leading edges.

The subsonic speed range is that range of speeds within which, all of the airflow over an aircraft is less than Mach 1. The critical Mach number (Mcrit) is lowest free stream Mach number at which airflow over any part of the aircraft first reaches Mach 1. So the subsonic speed range includes all speeds that are less than Mcrit. |

| Transonic | 0.8–1.2 | 530–794 | 609–914 | 980–1,470 | 273–409 | Transonic aircraft nearly always have swept wings, causing the delay of drag-divergence, and often feature a design that adheres to the principles of the Whitcomb Area rule.

The transonic speed range is that range of speeds within which the airflow over different parts of an aircraft is between subsonic and supersonic. So the regime of flight from Mcrit up to Mach 1.3 is called the transonic range. |

| Supersonic | 1.2–5.0 | 794-3,308 | 915-3,806 | 1,470–6,126 | 410–1,702 | The supersonic speed range is that range of speeds within which all of the airflow over an aircraft is supersonic (more than Mach 1). But airflow meeting the leading edges is initially decelerated, so the free stream speed must be slightly greater than Mach 1 to ensure that all of the flow over the aircraft is supersonic. It is commonly accepted that the supersonic speed range starts at a free stream speed greater than Mach 1.3.

Aircraft designed to fly at supersonic speeds show large differences in their aerodynamic design because of the radical differences in the behavior of flows above Mach 1. Sharp edges, thin aerofoil-sections, and all-moving tailplane/canards are common. Modern combat aircraft must compromise in order to maintain low-speed handling; "true" supersonic designs include the F-104 Starfighter, MiG-31, North American XB-70 Valkyrie, SR-71 Blackbird, and BAC/Aérospatiale Concorde. |

| Hypersonic | 5.0–10.0 | 3,308–6,615 | 3,806–7,680 | 6,126–12,251 | 1,702–3,403 | The X-15, at Mach 6.72 is one of the fastest manned aircraft. Also, cooled nickel-titanium skin; highly integrated (due to domination of interference effects: non-linear behaviour means that superposition of results for separate components is invalid), small wings, such as those on the Mach 5 X-51A Waverider. |

| High-hypersonic | 10.0–25.0 | 6,615–16,537 | 7,680–19,031 | 12,251–30,626 | 3,403–8,508 | The NASA X-43, at Mach 9.6 is one of the fastest aircraft. Thermal control becomes a dominant design consideration. Structure must either be designed to operate hot, or be protected by special silicate tiles or similar. Chemically reacting flow can also cause corrosion of the vehicle's skin, with free-atomic oxygen featuring in very high-speed flows. Hypersonic designs are often forced into blunt configurations because of the aerodynamic heating rising with a reduced radius of curvature. |

| Re-entry speeds | >25.0 | >16,537 | >19,031 | >30,626 | >8,508 | Ablative heat shield; small or no wings; blunt shape. Russia's Avangard (hypersonic glide vehicle) reaches up to Mach 27. |

High-speed flow around objects

Flight can be roughly classified in six categories:

| Regime | Subsonic | Transonic | Speed of sound | Supersonic | Hypersonic | Hypervelocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mach | <0.8 | 0.8–1.2 | 1.0 | 1.2–5.0 | 5.0–10.0 | >8.8 |

For comparison: the required speed for low Earth orbit is approximately 7.5 km/s = Mach 25.4 in air at high altitudes.

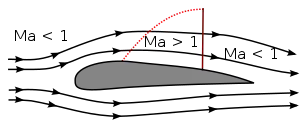

At transonic speeds, the flow field around the object includes both sub- and supersonic parts. The transonic period begins when first zones of M > 1 flow appear around the object. In case of an airfoil (such as an aircraft's wing), this typically happens above the wing. Supersonic flow can decelerate back to subsonic only in a normal shock; this typically happens before the trailing edge. (Fig.1a)

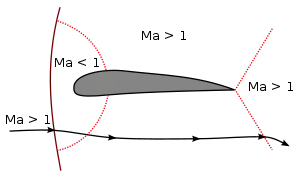

As the speed increases, the zone of M > 1 flow increases towards both leading and trailing edges. As M = 1 is reached and passed, the normal shock reaches the trailing edge and becomes a weak oblique shock: the flow decelerates over the shock, but remains supersonic. A normal shock is created ahead of the object, and the only subsonic zone in the flow field is a small area around the object's leading edge. (Fig.1b)

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Fig. 1. Mach number in transonic airflow around an airfoil; M < 1 (a) and M > 1 (b).

When an aircraft exceeds Mach 1 (i.e. the sound barrier), a large pressure difference is created just in front of the aircraft. This abrupt pressure difference, called a shock wave, spreads backward and outward from the aircraft in a cone shape (a so-called Mach cone). It is this shock wave that causes the sonic boom heard as a fast moving aircraft travels overhead. A person inside the aircraft will not hear this. The higher the speed, the more narrow the cone; at just over M = 1 it is hardly a cone at all, but closer to a slightly concave plane.

At fully supersonic speed, the shock wave starts to take its cone shape and flow is either completely supersonic, or (in case of a blunt object), only a very small subsonic flow area remains between the object's nose and the shock wave it creates ahead of itself. (In the case of a sharp object, there is no air between the nose and the shock wave: the shock wave starts from the nose.)

As the Mach number increases, so does the strength of the shock wave and the Mach cone becomes increasingly narrow. As the fluid flow crosses the shock wave, its speed is reduced and temperature, pressure, and density increase. The stronger the shock, the greater the changes. At high enough Mach numbers the temperature increases so much over the shock that ionization and dissociation of gas molecules behind the shock wave begin. Such flows are called hypersonic.

It is clear that any object traveling at hypersonic speeds will likewise be exposed to the same extreme temperatures as the gas behind the nose shock wave, and hence choice of heat-resistant materials becomes important.

High-speed flow in a channel

As a flow in a channel becomes supersonic, one significant change takes place. The conservation of mass flow rate leads one to expect that contracting the flow channel would increase the flow speed (i.e. making the channel narrower results in faster air flow) and at subsonic speeds this holds true. However, once the flow becomes supersonic, the relationship of flow area and speed is reversed: expanding the channel actually increases the speed.

The obvious result is that in order to accelerate a flow to supersonic, one needs a convergent-divergent nozzle, where the converging section accelerates the flow to sonic speeds, and the diverging section continues the acceleration. Such nozzles are called de Laval nozzles and in extreme cases they are able to reach hypersonic speeds (Mach 13 (15,900 km/h; 9,900 mph) at 20 °C).

An aircraft Machmeter or electronic flight information system (EFIS) can display Mach number derived from stagnation pressure (pitot tube) and static pressure.

Calculation

When the speed of sound is known, the Mach number at which an aircraft is flying can be calculated by

where:

- M is the Mach number

- u is velocity of the moving aircraft and

- c is the speed of sound at the given altitude (more properly temperature)

and the speed of sound varies with the thermodynamic temperature as:

where:

- is the ratio of specific heat of a gas at a constant pressure to heat at a constant volume (1.4 for air)

- is the specific gas constant for air.

- is the static air temperature.

If the speed of sound is not known, Mach number may be determined by measuring the various air pressures (static and dynamic) and using the following formula that is derived from Bernoulli's equation for Mach numbers less than 1.0. Assuming air to be an ideal gas, the formula to compute Mach number in a subsonic compressible flow is:[9]

where:

- qc is impact pressure (dynamic pressure) and

- p is static pressure

- is the ratio of specific heat of a gas at a constant pressure to heat at a constant volume (1.4 for air)

- is the specific gas constant for air.

The formula to compute Mach number in a supersonic compressible flow is derived from the Rayleigh supersonic pitot equation:

Calculating Mach number from pitot tube pressure

Mach number is a function of temperature and true airspeed. Aircraft flight instruments, however, operate using pressure differential to compute Mach number, not temperature.

Assuming air to be an ideal gas, the formula to compute Mach number in a subsonic compressible flow is found from Bernoulli's equation for M < 1 (above):[9]

The formula to compute Mach number in a supersonic compressible flow can be found from the Rayleigh supersonic pitot equation (above) using parameters for air:

where:

- qc is the dynamic pressure measured behind a normal shock.

As can be seen, M appears on both sides of the equation, and for practical purposes a root-finding algorithm must be used for a numerical solution (the equation's solution is a root of a 7th-order polynomial in M2 and, though some of these may be solved explicitly, the Abel–Ruffini theorem guarantees that there exists no general form for the roots of these polynomials). It is first determined whether M is indeed greater than 1.0 by calculating M from the subsonic equation. If M is greater than 1.0 at that point, then the value of M from the subsonic equation is used as the initial condition for fixed point iteration of the supersonic equation, which usually converges very rapidly.[9] Alternatively, Newton's method can also be used.

See also

- Critical Mach number

- Machmeter – Flight instrument

- Ramjet – Atmospheric jet engine designed to operate at supersonic speeds

- Scramjet – Jet engine where combustion takes place in supersonic airflow

- Speed of sound – Speed of sound wave through elastic medium

- True airspeed

- Orders of magnitude (speed)

Notes

- Young, Donald F.; Munson, Bruce R.; Okiishi, Theodore H.; Huebsch, Wade W. (21 December 2010). A Brief Introduction to Fluid Mechanics (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-470-59679-1. LCCN 2010038482. OCLC 667210577. OL 24479108M.

- Graebel, William P. (19 January 2001). Engineering Fluid Mechanics (1st ed.). CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-56032-733-2. OCLC 1034989004. OL 9794889M.

- "Ernst Mach". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- Jakob Ackeret: Der Luftwiderstand bei sehr großen Geschwindigkeiten. Schweizerische Bauzeitung 94 (Oktober 1929), pp. 179–183. See also: N. Rott: Jakob Ackert and the History of the Mach Number. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 17 (1985), pp. 1–9.

- Bodie, Warren M., The Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Widewing Publications ISBN 0-9629359-0-5.

- Nancy Hall (ed.). "Mach Number". NASA.

- Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Table 1, Pitman Publishing London, ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- Kundu, P.J.; Cohen, I.M.; Dowling, D.R. (2012). Fluid Mechanics (5th ed.). Academic Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-12-382100-3.

- Olson, Wayne M. (2002). "AFFTC-TIH-99-02, Aircraft Performance Flight Testing." (PDF). Air Force Flight Test Center, Edwards AFB, CA, United States Air Force. Archived September 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Gas Dynamics Toolbox Calculate Mach number and normal shock wave parameters for mixtures of perfect and imperfect gases.

- NASA's page on Mach Number Interactive calculator for Mach number.

- NewByte standard atmosphere calculator and speed converter