Marine protected area

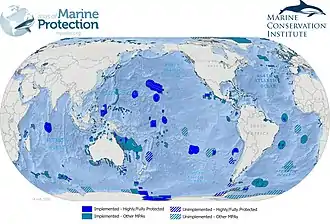

Marine protected areas (MPA) are protected areas of seas, oceans, estuaries or in the US, the Great Lakes.[2] These marine areas can come in many forms ranging from wildlife refuges to research facilities.[3] MPAs restrict human activity for a conservation purpose, typically to protect natural or cultural resources.[4] Such marine resources are protected by local, state, territorial, native, regional, national, or international authorities and differ substantially among and between nations. This variation includes different limitations on development, fishing practices, fishing seasons and catch limits, moorings and bans on removing or disrupting marine life. In some situations (such as with the Phoenix Islands Protected Area), MPAs also provide revenue for countries, potentially equal to the income that they would have if they were to grant companies permissions to fish.[5] The value of MPA to mobile species is unknown.[6]

There are a number of global examples of large marine conservation areas. The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, is situated in the central Pacific Ocean, around Hawaii, occupying an area of 1.5 million square kilometers.[7] The area is rich in wild life, including the green turtle and the Hawaiian monkfish, alongside 7,000 other species, and 14 million seabirds.[8] In 2017 the Cook Islands passed the Marae Moana Act designating the whole of the country's marine exclusive economic zone, which has an area of 1.9 million square kilometers as a zone with the purpose of protecting and conserving the "ecological, biodiversity and heritage values of the Cook Islands marine environment".[9]: 355 Other large marine conservation areas include those around Antarctica, New Caledonia, Greenland, Alaska, Ascension island, and Brazil.

As areas of protected marine biodiversity expand, there has been an increase in ocean science funding, essential for preserving marine resources.[10] In 2020, only around 7.5 to 8% of the global ocean area falls under a conservation designation.[11] This area is equivalent to 27 million square kilometres, equivalent to the land areas of Russia and Canada combined, although some argue that the effective conservation zones (ones with the strictest regulations) occupy only 5% of the ocean area (about equivalent to the land area of Russia alone). Marine conservation zones, as with their terrestrial equivalents, vary in terms of rules and regulations. Few zones rule out completely any sort of human activity within their area, as activities such as fishing, tourism, and transport of essential goods and services by ship, are part of the fabric of nation states.

Terminology

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a protected area as:[12][13]

A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.

This definition is intended to make it more difficult to claim MPA status for regions where exploitation of marine resources occurs. If there is no defined long-term goal for conservation and ecological recovery and extraction of marine resources occurs, a region is not a marine protected area.[13]

"Marine protected area (MPA)" is a term for protected areas that include marine environment and biodiversity.

Other definitions by the IUCN include (2010):[14]

Any area of the intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment.

United States Executive Order 13158 in May 2000 established MPAs, defining them as:[15]

Any area of the marine environment that has been reserved by federal, state, tribal, territorial, or local laws or regulations to provide lasting protection for part or all of the natural and cultural resources therein.

The Convention on Biological Diversity defined the broader term of marine and coastal protected area (MCPA):[16]

Any defined area within or adjacent to the marine environment, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by legislation or other effective means, including custom, with the effect that its marine and/or coastal biodiversity enjoys a higher level of protection than its surroundings.

An apparently unique extension of the meaning is used by NOAA to refer to protected areas on the Great Lakes of North America.[2]

History

The form of marine protected areas trace the origins to the World Congress on National Parks in 1962. In 1976, a process was delivered to the excessive rights to every sovereign state to establish marine protected areas at over 200 nautical miles.

Over the next two decades, a scientific body of evidence marked the utility in the designation of marine protected areas. In the aftermath of the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, an international target was established with the encompassment of ten percent of the world's marine protected areas.

On 28 October 2016 in Hobart, Australia, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources agreed to establish the first Antarctic and largest marine protected area in the world encompassing 1.55 million km2 (600,000 sq mi) in the Ross Sea.[17] Other large MPAs are in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans, in certain exclusive economic zones of Australia and overseas territories of France, the United Kingdom and the United States, with major (990,000 square kilometres (380,000 sq mi) or larger) new or expanded MPAs by these nations since 2012—such as Natural Park of the Coral Sea, Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, Coral Sea Commonwealth Marine Reserve and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Marine Protected Area. When counted with MPAs of all sizes from many other countries, as of August 2016 there are more than 13,650 MPAs, encompassing 2.07% of the world's oceans, with half of that area – encompassing 1.03% of the world's oceans – receiving complete "no-take" designation.[18]

Classifications

Several types of compliant MPA can be distinguished:

- A totally marine area with no significant terrestrial parts.

- An area containing both marine and terrestrial components, which can vary between two extremes; those that are predominantly maritime with little land (for example, an atoll would have a tiny island with a significant maritime population surrounding it), or that is mostly terrestrial.

- Marine ecosystems that contain land and intertidal components only. For example, a mangrove forest would contain no open sea or ocean marine environment, but its river-like marine ecosystem nevertheless complies with the definition.

IUCN offered seven categories of protected area, based on management objectives and four broad governance types.

| Cat | IUCN Protected Area Management Categories: |

|---|---|

Ia |

Strict nature reserve A marine reserve usually connotes "maximum protection", where all resource removals are strictly prohibited. In countries such as Kenya and Belize, marine reserves allow for low-risk removals to sustain local communities. |

Ib |

Wilderness area |

II |

National park Marine parks emphasize the protection of ecosystems but allow light human use. A marine park may prohibit fishing or extraction of resources, but allow recreation. Some marine parks, such as those in Tanzania, are zoned and allow activities such as fishing only in low risk areas. |

III |

Natural monuments or features Established to protect historical sites such as shipwrecks and cultural sites such as aboriginal fishing grounds. |

IV |

Habitat/species management area Established to protect a certain species, to benefit fisheries, rare habitat, as spawning/nursing grounds for fish, or to protect entire ecosystems. |

V |

Protected seascape Limited active management, as with protected landscapes. |

VI |

Sustainable use of natural resources |

Related protected area categories include the following;

- World Heritage Site (WHS) – an area exhibiting extensive natural or cultural history. Maritime areas are poorly represented, however, with only 46 out of over 800 sites.

- Man and the Biosphere – UNESCO program that promotes "a balanced relationship between humans and the biosphere". Under article 4, biosphere reserves must "encompass a mosaic of ecological systems", and thus combine terrestrial, coastal, or marine ecosystems. In structure they are similar to Multiple-use MPAs, with a core area ringed by different degrees of protection.[20]

- Ramsar site – must meet certain criteria for the definition of "Wetland" to become part of a global system. These sites do not necessarily receive protection, but are indexed by importance for later recommendation to an agency that could designate it a protected area.[21]

While "area" refers to a single contiguous location, terms such as "network", "system", and "region" that group MPAs are not always consistently employed."System" is more often used to refer to an individual MPA, whereas "region" is defined by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre as:[22]

A collection of individual MPAs operating cooperatively, at various spatial scales and with a range of protection levels that are designed to meet objectives that a single reserve cannot achieve.

At the 2004 Convention on Biological Diversity, the agency agreed to use "network" on a global level, while adopting system for national and regional levels. The network is a mechanism to establish regional and local systems, but carries no authority or mandate, leaving all activity within the "system".[23]

No take zones (NTZs), are areas designated in a number of the world's MPAs, where all forms of exploitation are prohibited and severely limits human activities. These no take zones can cover an entire MPA, or specific portions. For example, the 1,150,000 square kilometres (440,000 sq mi) Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, the world's largest MPA (and largest protected area of any type, land or sea), is a 100% no take zone.[24]

Related terms include; specially protected area (SPA), Special Area of Conservation (SAC), the United Kingdom's marine conservation zones (MCZs),[25] or area of special conservation (ASC) etc. which each provide specific restrictions.

Stressors

Stressors that affect oceans include the impact of extractive industries, marine pollution, and changes to the ocean's chemistry (ocean acidification) resulting from elevated carbon dioxide levels, due to our greenhouse gas emissions (see also effects of climate change on oceans).[26]

MPAs have been cited as the ocean's single greatest hope for increasing the resilience of the marine environment to such stressors.[26] Well-designed and managed MPAs developed with input and support from interested stakeholders can conserve biodiversity and protect and restore fisheries.

Economics

MPAs can help sustain local economies by supporting fisheries and tourism. For example, Apo Island in the Philippines made protected one quarter of their reef, allowing fish to recover, jumpstarting their economy. This was shown in the film, Resources at Risk: Philippine Coral Reef.[27] A 2016 report by the Center for Development and Strategy found that programs like the United States National Marine Sanctuary system can develop considerable economic benefits for communities through Public–private partnerships.[28] They can be self-financed through a surrounding "conservation finance area" in which a limited number licenses are granted to benefit from the spillover of the marine protected area.[29]

Management

Typical MPAs restrict fishing, oil and gas mining and/or tourism. Other restrictions may limit the use of ultrasonic devices like sonar (which may confuse the guidance system of cetaceans), development, construction and the like. Some fishing restrictions include "no-take" zones, which means that no fishing is allowed. Less than 1% of US MPAs are no-take.

Ship transit can also be restricted or banned, either as a preventive measure or to avoid direct disturbance to individual species. The degree to which environmental regulations affect shipping varies according to whether MPAs are located in territorial waters, exclusive economic zones, or the high seas. The law of the sea regulates these limits.

Most MPAs have been located in territorial waters, where the appropriate government can enforce them. However, MPAs have been established in exclusive economic zones and in international waters. For example, Italy, France and Monaco in 1999 jointly established a cetacean sanctuary in the Ligurian Sea named the Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean Marine Mammals. This sanctuary includes both national and international waters. Both the CBD and IUCN recommended a variety of management systems for use in a protected area system. They advocated that MPAs be seen as one of many "nodes" in a network of protected areas.[30] The following are the most common management systems:

Seasonal and temporary management—Activities, most critically fishing, are restricted seasonally or temporarily, e.g., to protect spawning/nursing grounds or to let a rapidly reducing species recover.

Multiple-use MPAs—These are the most common and arguably the most effective. These areas employ two or more protections. The most important sections get the highest protection, such as a no take zone and are surrounded with areas of lesser protections.

Community involvement and related approaches—Community-managed MPAs empower local communities to operate partially or completely independent of the governmental jurisdictions they occupy. Empowering communities to manage resources can lower conflict levels and enlist the support of diverse groups that rely on the resource such as subsistence and commercial fishers, scientists, recreation, tourism businesses, youths and others. Mistrust between fishermen and regulating authorities is of central importance there, and needs to be addressed. Recent evidence from regions like Scandinavia, Spain, Portugal or Canada reveals success stories based on the tested cooperation between marine scientists and fishermen in jointly managing coastal marine reserves.[32]

Marine Protected Area Networks

Marine Protected Area Networks or MPA networks have been defined as "A group of MPAs that interact with one another ecologically and/or socially form a network".[27]

These networks are intended to connect individuals and MPAs and promote education and cooperation among various administrations and user groups. "MPA networks are, from the perspective of resource users, intended to address both environmental and socio-economic needs, complementary ecological and social goals and designs need greater research and policy support".[27]

Filipino communities connect with one another to share information about MPAs, creating a larger network through the social communities' support.[33] Emerging or established MPA networks can be found in Australia, Belize, the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Mexico.[27]

Future approaches

To be truly representative of the ocean and its range of marine resources, marine conservation parks should encompass the great variety of ocean geological and geographical terrains, as these, in turn, influence the biosphere around them. As time progresses it would be strategically advantageous to develop parks that include oceanic features such as ocean ridges, ocean trenches, island arc systems, ocean seamounts, ocean plateaus, and abyssal plains, which occupy half the earth's surface. Another factor that will influence the development of marine conservation areas is ownership. Who owns the world's oceans?[34] Approximately 64% of the world's oceans are "international waters" and subject to regulations such as the Law of the Sea and the governance of UN bodies such as the International Seabed Authority. The remaining 36% of the ocean is under the governance of individual countries within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). Some individual national EEZ's cover very large areas, such as France and USA (>11 million km2), and Australia, Russia, UK, and Indonesia (>6 million km2). Some states have very small land areas but extremely large EEZ's such as Kiribati, the Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, and Cook Islands who have individual EEZ areas of between 1.9 and 3.5 million km2. The national EEZ's are the ones where governance is easier, and agreements to create marine parks are within national jurisdictions, such as is the case with Marae Moana and the Cook islands.

One alternative to imposing MPAs on an indigenous population is through the use of Indigenous Protected Areas, such as those in Australia.

International efforts

The 17th International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) General Assembly in San Jose, California, the 19th IUCN assembly and the fourth World Parks Congress all proposed to centralise the establishment of protected areas. The World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 called for

the establishment of marine protected areas consistent with international laws and based on scientific information, including representative networks by 2012.[35]

The Evian agreement, signed by G8 Nations in 2003, agreed to these terms. The Durban Action Plan, developed in 2003, called for regional action and targets to establish a network of protected areas by 2010 within the jurisdiction of regional environmental protocols.It recommended establishing protected areas for 20 to 30% of the world's oceans by the goal date of 2012. The Convention on Biological Diversity considered these recommendations and recommended requiring countries to set up marine parks controlled by a central organization before merging them. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed to the terms laid out by the convention, and in 2004, its member nations committed to the following targets;[36]

- By 2006 complete an area system gap analysis at national and regional levels.

- By 2008 address the less represented marine ecosystems, accounting for those beyond national jurisdiction in accordance.

- By 2009 designate the protected areas identified through the gap analysis.

- By 2012 complete the establishment of a comprehensive and ecologically representative network.

"The establishment by 2010 of terrestrial and by 2012 for marine areas of comprehensive, effectively managed, and ecologically representative national and regional systems of protected areas that collectively, inter alia through a global network, contribute to achieving the three objectives of the Convention and the 2010 target to significantly reduce the current late of biodiversity loss at the global, regional, national, and sub-national levels and contribute to poverty reduction and the pursuit of sustainable development."[38]

Global goals

The UN later endorsed another decision, Decision VII/15, in 2006:

Effective conservation of 10% of each of the world's ecological regions by 2010.

– United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Decision VII/15[39]

The 10% conservation goal is also found in Sustainable Development Goal 14 (which is part of the Convention on Biological Diversity) and which sets this 10% goal to a later date (2020). In 2017, the UN held the United Nations Ocean Conference aiming to find ways and urge for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14. In that 2017 conference, it was clear that just between 3.6 and 5.7% of the world's oceans were protected, meaning another 6.4 to 4.3% of the world's oceans needed to be protected within 3 years.[40][41] The 10% protection goal is described as a "baby step" as 30% is the real amount of ocean protection scientists agree on that should be implemented.[40]

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The Antarctic Treaty System

On 7 April 1982, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention) came into force after discussions began in 1975 between parties of the then-current Antarctic Treaty to limit large-scale exploitation of krill by commercial fisheries. The Convention bound contracting nations to abide by previously agreed upon Antarctic territorial claims and peaceful use of the region while protecting ecosystem integrity south of the Antarctic Convergence and 60 S latitude. In so doing, it also established a commission of the original signatories and acceding parties called the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) to advance these aims through protection, scientific study, and rational use, such as harvesting, of those marine resources. Though separate, the Antarctic Treaty and CCAMLR, make up part the broader system of international agreements called the Antarctic Treaty System. Since 1982, the CCAMLR meets annually to implement binding conservations measures like the creation of 'protected areas' at the suggestion of the convention's scientific committee.

In 2009, the CCAMLR created the first 'high-seas' MPA entirely within international waters over the southern shelf of the South Orkney Islands. This area encompasses 94,000 square kilometres (36,000 sq mi) and all fishing activity including transhipment, and dumping or discharge of waste is prohibited with the exception of scientific research endeavors.[42] On 28 October 2016, the CCAMLR, composed of 24 member countries and the European Union at the time, agreed to establish the world's largest marine park encompassing 1.55 million km2 (600,000 sq mi) in the Ross Sea after several years of failed negotiations. Establishment of the Ross Sea MPA required unanimity of the commission members and enforcement will begin in December 2017. However, due to a sunset provision inserted into the proposal, the new marine park will only be in force for 35 years.[43]

National Targets

Many countries have established national targets, accompanied by action plans and implementations. The UN Council identified the need for countries to collaborate with each other to establish effective regional conservation plans. Some national targets are listed in the table below[44]

| Country | Plan of action |

|---|---|

| American Samoa | 20% of reefs to be protected by 2010 |

| Australia – South Australia | 19 marine protected areas by 2010 |

| Bahamas | 20% of the marine ecosystem protected for fishery replenishment by 2010. 20% of coastal and marine habitats by 2015. |

| Belize | 20% of bioregions.

30% of Coral reefs. 60% of turtle nesting sites. 30% of Manatee distribution. 60% of American crocodile nesting. 80% of breeding areas. |

| Canada | 10% marine conservation areas by 2020.[45] |

| Chile | 10% of marine areas by 2010. National network for organization by 2015. |

| Cuba | 22% of land habitat, including:

|

| Dominican Republic | 20% of marine and coastal by 2020. |

| Micronesia | 30% of shoreline ecosystems by 2020. |

| Fiji | 30% of reefs by 2015.

30% of water managed by marine protected areas by 2020. |

| Germany | 38% of water managed by the marine protected network. (no set date) |

| Grenada | 25% of nearby marine resources by 2020. |

| Guam | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| Indonesia | 100,000 km2 by 2010.

200,000 km2 by 2020. |

| Republic of Ireland | 14% of territorial waters as of 2009[46] |

| Isle of Man | 10% of Manx waters as 'effectively managed, ecologically representative and well-connected protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures' by 2020. As of June 2016, approximately 3% of Manx waters were protected as a Marine Nature Reserve, with additional areas subject to seasonal or temporary protection.[47] |

| Jamaica | 20% of marine habitats by 2020. |

| Madagascar | 100,000 km2 by 2012. |

| Marshall Islands | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| New Zealand | 20% of marine environment by 2010. |

| North Mariana Islands | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| Palau | 30% of nearby marine ecosystem by 2020. |

| Peru | Marine protected area system established by 2015. |

| Philippines | 10% fully protected by 2020. |

| Senegal | Creation of MPA network. (no set date) |

| South Africa | 10% of exclusive economic zone by 2020 |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 20% of marine areas by 2020. |

| Tanzania | 10% of marine area by 2010; 20% by 2020. |

| United Kingdom | Establish an ecologically coherent network of marine protected areas by 2012. |

| United States – California | 29 MPAs covering 18% of state marine area with 243 square kilometres (94 sq mi) at maximum protection. |

The prevalent practice of area-based targets was criticized in 2019 by a group of environmental scientists because politicians tended to protect parts of the oceans where little fishing happened to meet the goals. The lack of fishing in these areas made them easy to protect, but it also had little positive impact.[48]

Regional and national efforts

The marine protected area network is still in its infancy. As of October 2010, approximately 6,800 MPAs had been established, covering 1.17% of global ocean area. Protected areas covered 2.86% of exclusive economic zones (EEZs).[49] MPAs covered 6.3% of territorial seas.[50] Many prohibit the use of harmful fishing techniques yet only 0.01% of the ocean's area is designated as a "no take zone".[51] This coverage is far below the projected goal of 20%-30%[52][53] Those targets have been questioned mainly due to the cost of managing protected areas and the conflict that protections have generated with human demand for marine goods and services.[54][55]

South Africa

The marine protected areas of South Africa are in an area of coastline or ocean within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the Republic of South Africa that is protected in terms of specific legislation for the benefit of the environment and the people who live in and use it.[56] An MPA is a place where marine life can thrive under less pressure than unprotected areas. They are like underwater parks, and this healthy environment can benefit neighbouring areas.[57][58]

There are a total of 42 marine protected areas in the South African EEZ, after consolidation, with a total area of 15.5% of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The target was to have 10% of the oceanic waters protected by 2020. All but one of the MPAs are in the exclusive economic zone off continental South Africa, and one is off the Prince Edward Islands in the Southern Ocean. Without the large Prince Edward Islands MPA, South Africa has 41 MPAs covering 5.4% of its continental EEZ. This achieves United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14.5 for conservation of marine and coastal areas, and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 Aichi Target 11.[59][60]

People can take part in a wide range of non-consumptive activities in all of South Africa's MPAs, and some parts of some MPAs are zoned for limited consumptive activities.[58] Some of these activities require a permit, which is a form of taxation.Greater Caribbean

The Greater Caribbean subdivision encompasses an area of about 5,700,000 square kilometres (2,200,000 sq mi) of ocean and 38 nations. The area includes island countries like the Bahamas and Cuba, and the majority of Central America. The Convention for Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region (better known as the Cartagena Convention) was established in 1983. Protocols involving protected areas were ratified in 1990. As of 2008, the region hosted about 500 MPAs. Coral reefs are the best represented.

Two networks are under development, the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (a long barrier reef that borders the coast of much of Central America), and the "Islands in the Stream" program (covering the Gulf of Mexico).[61]

Asia

Southeast Asia is a global epicenter for marine diversity. 12% of its coral reefs are in MPAs. The Philippines have some the world's best coral reefs and protect them to attract international tourism. Most of the Philippines' MPAs are established to secure protection for its coral reef and sea grass habitats. Indonesia has MPAs designed for tourism and relies on tourism as a main source of income.[27]

China

China has developed its unique MPA management system, which divides MPAs into two main categories: Marine Natural Reserves (MNRs) and Special Marine Protected Areas (SMPAs).[62][63][64] As of 2016, China has designated 267 MPAs, including 160 MNRs and 107 SMPAs, covering nearly 4% of the sea area.[62]

MNRs are the no-take areas under comprehensive protection that prohibit any kind of resource exploitation.[64] Unlike such traditional MPAs, SMPAs have been established in China since 2002.[62] SMPAs allow the use of marine resources in a supervised and sustainable way, aiming at reducing local development conflicts caused by MNRs (such as the survival of coastal fishermen) and greater matching of national economic development strategies.[62][63][64] Depending on local ecological considerations, SMPAs will subdivide into different functional zones. Areas with rare and endangered species or damaged and fragile environments are strict no-take areas and ecological restoration areas, while other areas will be considered sustainable resource use zone for current use and reserved zone for future use.[64]

Despite all the efforts, as China constructs MPA based on administrative hierarchy (national, provincial, municipal, and county), there exist problems of fragmentized division and inconsistent enforcement of MPAs.[64]

Philippines

The Philippines host one of the most highly biodiverse regions, with 464 reef-building coral species. Due to overfishing, destructive fishing techniques, and rapid coastal development, these are in rapid decline. The country has established some 600 MPAs. However, the majority are poorly enforced and are highly ineffective. However, some have positively impacted reef health, increased fish biomass, decreased coral bleaching and increased yields in adjacent fisheries. One notable example is the MPA surrounding Apo Island.[65]

Latin America

Latin America has designated one large MPA system. As of 2008, 0.5% of its marine environment was protected, mostly through the use of small, multiple-use MPAs.[66]

Mexico designed a Marine Strategy that goes from the years 2018-2021.[67]

Pacific Ocean

Governments in the "South Pacific network" (ranging from Belize to Chile) adopted the Lima convention and action plan in 1981. An MPA-specific protocol was ratified in 1989. The permanent commission on the exploitation and conservation on the marine resources of the South Pacific promotes the exchange of studies and information among participants.[66]

The region is currently running one comprehensive cross-national program, the Tropical Eastern Pacific Marine Corridor Network, signed in April 2004. The network covers about 211,000,000 square kilometres (81,000,000 sq mi).[66]

The Marae Moana Conservation Park in Cook Islands has many stakeholders within its governance structure, including a variety of Government Ministries, NGOs, traditional landowners, and society representatives.[9] The Marae Moana conservation area is managed through a spatial zoning principle, whereby specific designations are given to specific zones, though these designations may change over time. For example, some areas may allow fishing, whilst fishing may be prohibited in other areas.

The "North Pacific network" covers the western coasts of Mexico, Canada, and the U.S. The "Antigua Convention" and an action plan for the north Pacific region were adapted in 2002. Participant nations manage their own national systems.[66] In 2010–2011, the State of California completed hearings and actions via the state Department of Fish and Game to establish new MPAs.[68]

Indian Ocean

In exchange for some of its national debt being written off, the Seychelles designates two new marine protected areas in the Indian Ocean, covering about 210,000 square kilometres (81,000 sq mi). It is the result of a financial deal, brokered in 2016 by The Nature Conservancy.[69][70]

In 2021 Australia announced the creation of 2 national marine parks in size of 740,000 square kilometers. With those parks 45% of the Australian marine territory will be protected.[71]

Ten countries in the Western Indian Ocean have launched the "Great Blue Wall" initiative, which seeks to create a network of linked MPAs throughout the region. These are generally expected to be under IUCN category IV protection, which allows for local fishing but prohibits industrial exploitation.[72][73]

Mediterranean Sea

The Natura 2000 ecological MPA network in the European Union included MPAs in the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea and the Baltic Sea. The member states had to define NATURA 2000 areas at sea in their Exclusive Economic Zone.

Two assessments, conducted thirty years apart, of three Mediterranean MPAs, demonstrate that proper protection allows commercially valuable and slow-growing red coral (Corallium rubrum) to produce large colonies in shallow water of less than 50 metres (160 ft). Shallow-water colonies outside these decades-old MPAs are typically very small. The MPAs are Banyuls, Carry-le-Rouet and Scandola, off the island of Corsica.[74]

- The Mediterranean Science Commission proposed the creation of eight large, international, MPAs ("CIESM Marine Peace Parks") with the dual benefits of protecting unique oceanographic features and mitigating trans-frontier conflicts [75]

- WWF together with other partners[76] proposed the creation of MedPan (Mediterranean Network of Marine Protected Areas Managers) which aims to protect 10% of the surface of the Mediterranean by 2020.[77]

A 2018 study published in Science found that trawling is more intense inside official EU marine sanctuaries and that endangered fish species such as sharks and rays are more common outside them.[78]

United States

As of June 2020, 26% of U.S. waters (including the Great Lakes) wwere in an MPA. Only 3% of US waters are no-take MPAs. Almost all of the no-take zones are located in two large MPAs in the remote Pacific Ocean, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.[79]

United Kingdom and British Overseas Territories

Near half of England's seas are MPAs. Those MPAs only ban in specific places some of the most damaging activities.[80] In 2020, Greenpeace revealed that in 2019 the UK legally allowed industrial boats to fish in the Marine protected area. This point is related to the concern of overfishing, while fishing is an object to the ongoing trade negotiations between the EU and the UK. Result of those negotiations might replace Common Fisheries Policy in the UK.

United Kingdom

There are a number of marine protected areas around the coastline of the United Kingdom, known as Marine Conservation Zones in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and Marine Protected Areas in Scotland.[81][82] They are to be found in inshore and offshore waters.[83] In June 2020, a review led by Richard Benyon MP, stated that nearly 50 areas around the UK coastline should become Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs). This would see the banning of dredging, sewage dumping, drilling, offshore wind-turbine construction and catch-and-release sea fishing.[84]

British Overseas Territories

The United Kingdom is also creating marine protected reserves around several British Overseas Territories. The UK is responsible for 6.8 million square kilometres of ocean around the world, larger than all but four other countries.[85] In 2016 the UK government established the Blue Belt Programme to enhance the protection and management of the marine environment.[86]

The Chagos Marine Protected Area in the Indian Ocean was established in 2010 as a "no-take-zone". With a total surface area of 640,000 square kilometres (250,000 sq mi), it was the world's largest contiguous marine reserve.[87][88] In March 2015, the UK announced the creation of a marine reserve around the Pitcairn Islands in the Southern Pacific Ocean to protect its special biodiversity. The area of 830,000 square kilometres (320,000 sq mi) surpassed the Chagos Marine Protected Area as the world's largest contiguous marine reserve,[89][90] until the August 2016 expansion of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the United States to 1,510,000 square kilometres (580,000 sq mi).

In January 2016, the UK government announced the intention to create a marine protected area around Ascension Island. The protected area will be 234,291 square kilometres (90,460 sq mi), half of which will be closed to fishing.[91]

On 13 November 2020 it was announced that the 687,247 square kilometres (265,348 sq mi) of the waters surrounding the Tristan da Cunha and neighboring islands will become a Marine Protection Zone. The move will make the zone the largest no-take zone in the Atlantic and the fourth largest on the planet.[92][93]

Notable marine protected areas

- The Bowie Seamount Marine Protected Area off the coast of British Columbia, Canada.

- The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Queensland, Australia.

- The Ligurian Sea Cetacean Sanctuary in the seas of Italy, Monaco and France.

- The Dry Tortugas National Park in the Florida Keys, USA.

- The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii.

- The Phoenix Islands Protected Area, Kiribati.[94]

- The Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary in California, USA.[95]

- The Chagos Marine Protected Area in the Indian Ocean.[96]

- The Wadden Sea bordering the North Sea in the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark.

Marine protected areas as percentage of territorial waters

The following shows a list of countries and their marine protected areas as percentage of their territorial waters (click "show" to expand).[97]

| Country | MPA in % of territorial waters in 2017 |

|---|---|

| Albania | 2.72 |

| Algeria | 0.09 |

| American Samoa | 8.72 |

| Angola | 0.00 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 0.18 |

| Argentina | 3.80 |

| Aruba | 0.00 |

| Australia | 40.56 |

| Azerbaijan | 0.44 |

| Bahamas, The | 7.92 |

| Bahrain | 1.24 |

| Bangladesh | 5.36 |

| Barbados | 0.01 |

| Belgium | 36.66 |

| Belize | 10.08 |

| Benin | 0.00 |

| Bermuda | 0.00 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.00 |

| Brazil | 26.62 |

| British Virgin Islands | 0.00 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.20 |

| Bulgaria | 8.10 |

| Cabo Verde | 0.00 |

| Cambodia | 0.19 |

| Cameroon | 3.41 |

| Canada | 0.87 |

| Cayman Islands | 0.08 |

| Chile | 28.81 |

| China | 5.41 |

| Colombia | 17.07 |

| Comoros | 0.02 |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 0.24 |

| Congo, Rep. | 3.21 |

| Costa Rica | 0.83 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 0.07 |

| Croatia | 8.54 |

| Cuba | 4.32 |

| Curaçao | 0.03 |

| Cyprus | 0.12 |

| Denmark | 17.85 |

| Djibouti | 0.17 |

| Dominica | 0.11 |

| Dominican Republic | 17.96 |

| Ecuador | 13.35 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 4.95 |

| El Salvador | 0.71 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 0.24 |

| Eritrea | 0.00 |

| Estonia | 18.62 |

| Faroe Islands | 0.01 |

| Fiji | 0.92 |

| Finland | 10.51 |

| France | 45.05 |

| French Polynesia | 0.00 |

| Gabon | 28.83 |

| Gambia, The | 0.07 |

| Georgia | 0.67 |

| Germany | 45.36 |

| Ghana | 0.10 |

| Gibraltar | 12.82 |

| Greece | 4.52 |

| Greenland | 4.52 |

| Grenada | 0.09 |

| Guam | 0.01 |

| Guatemala | 0.90 |

| Guinea | 0.53 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 10.01 |

| Guyana | 0.01 |

| Haiti | 0.00 |

| Honduras | 4.16 |

| Iceland | 0.38 |

| India | 0.17 |

| Indonesia | 3.06 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 0.80 |

| Iraq | 0.00 |

| Ireland | 2.33 |

| Isle of Man | 0.00 |

| Israel | 0.03 |

| Italy | 8.79 |

| Jamaica | 0.75 |

| Japan | 8.23 |

| Jordan | 35.59 |

| Kazakhstan | 1.05 |

| Kenya | 0.80 |

| Kiribati | 11.82 |

| Korea, Dem. People's Rep. | 0.02 |

| Korea, Rep. | 1.63 |

| Kuwait | 1.48 |

| Latvia | 16.04 |

| Lebanon | 0.21 |

| Liberia | 0.10 |

| Libya | 0.64 |

| Lithuania | 25.59 |

| Madagascar | 0.75 |

| Malaysia | 1.54 |

| Maldives | 0.05 |

| Malta | 6.27 |

| Marshall Islands | 0.27 |

| Mauritania | 4.15 |

| Mauritius | 0.00 |

| Mexico | 21.78 |

| Micronesia, Fed. Sts. | 0.02 |

| Monaco | 99.83 |

| Montenegro | 0.00 |

| Morocco | 0.26 |

| Mozambique | 2.23 |

| Myanmar | 2.33 |

| Namibia | 1.71 |

| Netherlands | 26.67 |

| New Caledonia | 96.59 |

| New Zealand | 30.37 |

| Nicaragua | 2.97 |

| Nigeria | 0.02 |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 33.25 |

| Norway | 0.83 |

| Oman | 0.12 |

| Pakistan | 0.77 |

| Palau | 82.99 |

| Panama | 1.68 |

| Papua New Guinea | 0.19 |

| Peru | 0.48 |

| Philippines | 1.16 |

| Poland | 22.57 |

| Portugal | 16.56 |

| Puerto Rico | 1.75 |

| Qatar | 1.68 |

| Romania | 23.10 |

| Russian Federation | 2.97 |

| Samoa | 0.09 |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 0.03 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2.49 |

| Senegal | 1.11 |

| Seychelles | 0.04 |

| Sierra Leone | 0.54 |

| Singapore | 0.01 |

| Sint Maarten (Dutch part) | 8.69 |

| Slovenia | 100.00 |

| Solomon Islands | 0.12 |

| South Africa | 12.06 |

| Spain | 8.37 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.07 |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | 0.17 |

| St. Lucia | 0.22 |

| St. Martin (French part) | 96.40 |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 0.22 |

| Sudan | 15.96 |

| Suriname | 1.54 |

| Sweden | 15.21 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 0.25 |

| Tanzania | 3.02 |

| Thailand | 1.88 |

| Timor-Leste | 1.37 |

| Togo | 0.20 |

| Tonga | 1.51 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0.05 |

| Tunisia | 1.04 |

| Turkey | 0.11 |

| Turkmenistan | 2.99 |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 0.10 |

| Tuvalu | 0.01 |

| Ukraine | 3.42 |

| United Arab Emirates | 11.27 |

| United Kingdom | 28.87 |

| United States | 41.06 |

| Uruguay | 0.72 |

| Vanuatu | 0.01 |

| Venezuela, RB | 3.49 |

| Vietnam | 0.56 |

| Virgin Islands (U.S.) | 0.85 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 0.47 |

Assessment

Managers and scientists use geographic information systems and remote sensing to map and analyze MPAs. NOAA Coastal Services Center compiled an "Inventory of GIS-Based Decision-Support Tools for MPAs". The report focuses on GIS tools with the highest utility for MPA processes.[98] Remote sensing uses advances in aerial photography image capture, pop-up archival satellite tags, satellite imagery, acoustic data, and radar imagery. Mathematical models that seek to reflect the complexity of the natural setting may assist in planning harvesting strategies and sustaining fishing grounds.[99] Other techniques such as on-site monitoring sensors, crowdsensing via local people, research and sampling endeavors, autonomous ships and underwater robots (UAV) could also be used and developed.[100]

Such data can then be used for assessing marine protection-quality and -extents. In 2021, 43 expert scientists published the first scientific framework version that – via integration, review, clarifications and standardization – enables coherent evaluation of levels of protection of marine protected areas and serve as a guide for improving, planning and monitoring these such as in efforts towards the 30%-protection-goal of the "Global Deal For Nature"[101] and the UN's Sustainable Development Goal 14.[102][103]

Coral reefs

Coral reef systems have been in decline worldwide. Causes include overfishing, pollution and ocean acidification. As of 2013 30% of the world's reefs were severely damaged. Approximately 60% will be lost by 2030 without enhanced protection.[104] Marine reserves with "no take zones" are the most effective form of protection.[105] Only about 0.01% of the world's coral reefs are inside effective MPAs.[106]

Fish

MPAs can be an effective tool to maintain fish populations; see refuge (ecology). The general concept is to create overpopulation within the MPA. The fish expand into the surrounding areas to reduce crowding, increasing the population of unprotected areas.[107] This helps support local fisheries in the surrounding area, while maintaining a healthy population within the MPA. Such MPAs are most commonly used for coral reef ecosystems.

One example is at Goat Island Bay in New Zealand, established in 1977. Research gathered at Goat Bay documented the spillover effect. "Spillover and larval export—the drifting of millions of eggs and larvae beyond the reserve—have become central concepts of marine conservation". This positively impacted commercial fishermen in surrounding areas.[108]

Another unexpected result of MPAs is their impact on predatory marine species, which in some conditions can increase in population. When this occurs, prey populations decrease. One study showed that in 21 out of 39 cases, "trophic cascades", caused a decrease in herbivores, which led to an increase in the quantity of plant life. (This occurred in the Malindi Kisite and Watamu Marian National Parks in Kenya; the Leigh Marine Reserve in New Zealand; and Brackett's Landing Conservation Area in the US.[109]

Success criteria

Both CBD and IUCN have criteria for setting up and maintaining MPA networks, which emphasize four factors:[110]

- Adequacy—ensuring that the sites have the size, shape, and distribution to ensure the success of selected species.

- Representability—protection for all of the local environment's biological processes

- Resilience—the resistance of the system to natural disaster, such as a tsunami or flood.

- Connectivity—maintaining population links across nearby MPAs.

Misconceptions

Misconceptions about MPAs include the belief that all MPAs are no-take or no-fishing areas. Less than 1 percent of US waters are no-take areas. MPA activities can include consumption fishing, diving and other activities.

Another misconception is that most MPAs are federally managed. Instead, MPAs are managed under hundreds of laws and jurisdictions. They can exist in state, commonwealth, territory and tribal waters.

Another misconception is that a federal mandate dedicates a set percentage of ocean to MPAs. Instead the mandate requires an evaluation of current MPAs and creates a public resource on current MPAs.[111]

Criticism

Land use right

Some existing and proposed MPAs have been criticized by indigenous populations and their supporters, as impinging on land usage rights. For example, the proposed Chagos Protected Area in the Chagos Islands is contested by Chagossians deported from their homeland in 1965 by the British as part of the creation of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). According to WikiLeaks CableGate documents,[112] the UK proposed that the BIOT become a "marine reserve" with the aim of preventing the former inhabitants from returning to their lands and to protect the joint UK/US military base on Diego Garcia Island.

Climate change

Oceans are the primary carbon sink and have been greatly affected by global warming, especially in recent years. The ability of existing MPA designs to cope with changes in marine biodiversity due to ocean acidification, sea level rise, sea surface temperature increase, oxygen reduction, and other marine environmental issues remains questionable.[113][114][115][116][117] Despite differences in species adaptations, warming has affected the habitats of some marine species, such as corals, to move from lower to higher latitudes.[113][114] If MPA assumes a relatively stable ecological environment within the area as before, it may become ineffective when the range of species distribution changes or becomes extensive.[115] Hence, there's need to incorporate the climate change adaptation to the framework.

Other critiques

Other critiques include: their cost (higher than that of passive management), conflicts with human development goals, inadequate scope to address factors such as climate change and invasive species.[54]

In Scotland, environmental groups have criticised the government for failing to enforce fishing rules around MPAs.[118]

See also

- Eco hotels as funding vehicles for marine protection initiatives

- Hope Spots: marine areas rich in biodiversity

- Important marine mammal area

- Law of the sea

- Marine park

- Marine spatial planning

- Special Protection Area

- Specially Protected Areas of Mediterranean Importance

- United States National Marine Sanctuary

References

- "Marine Protection Atlas". mpatlas.org. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- "What is a marine protected area?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

In the U.S., MPAs span a range of habitats, including the open ocean, coastal areas, inter-tidal zones, estuaries, and the Great Lakes.

- Administration, US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric. "What is a marine protect?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- "Marine Protected Areas". National Ocean Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- National Geographic Magazine, January 2011

- Kinney, Michael John; Simpfendorfer, Colin Ashley (2009). "Reassessing the value of nursery areas to shark conservation and management". Conservation Letters. 2 (2): 53–60. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2008.00046.x. ISSN 1755-263X.

- "National monument in Hawaii becomes world's largest marine protected area | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration". www.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- "Obama's Hawaii marine conservation area is just a drop in the ocean". The Guardian. 2016-09-06. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- Petterson, Michael G.; Kim, Hyeon-Ju; Gill, Joel C. (2021), Gill, Joel C.; Smith, Martin (eds.), "Conserve and Sustainably Use the Oceans, Seas, and Marine Resources", Geosciences and the Sustainable Development Goals, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 339–367, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-38815-7_14, ISBN 978-3-030-38814-0, S2CID 234955801, retrieved 2021-09-06

- "Goal 14 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- "How Much of the Ocean Is Really Protected in 2020?". pew.org. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- "Towards Networks of Marine Protected Areas - The MPA Plan of Action for IUCN's World Commission on Protected Areas" (PDF). IUCN. 2008-11-04. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "When is a Marine Protected Area really a Marine Protected Area". International Union for Conservation of Nature. 8 September 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Marine protected areas, why have them?". IUCN. 2010-02-01. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "Nomination of Existing Marine Protected Areas to the National System of Marine Protected Areas and Updates to the List of National System Marine Protected Areas". Federalregister.gov. 3 February 2011. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Marine Protected Areas (MPA) (2010-10-15). "Areas of Biodiversity Importance: Marine Protected Areas, 2010". Biodiversitya-z.org. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "CCAMLR to create world's largest Marine Protected Area". Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. 28 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Explore". MPAtlas. Marine Conservation Institute. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- "Foreign and Commonwealth Office, New Protection for Marine Life, April, 2010". Archived from the original on June 5, 2011.

- "Man and the Biosphere Programme". UNESCO. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands". Archived from the original on August 13, 2011.

- WDPA: Establishing Resilient Marine Protected Area Networks — Making It Happen, 2008

- UNEP: Marine Protected Areas and the Concept of Fisheries Refugia, 2006/

- "Papahānaumokuākea (Expansion) Marine National Monument, United States". MPAtlas. Marine Conservation Institute. Archived from the original on 2016-09-23. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- "Marine Conservation Zones". Naturalengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Laffoley, D. d'A., (ed.) 2008. Towards Networks of Marine Protected Areas. The MPA Plan of Action for IUCN's World Commission on Protected Areas. IUCN WCPA, Gland, Switzerland. 28 pp.

- Christie, P.; White, A. T. (2007). "Best Practices for Improved Governance of Coral Reef Marine Protected Areas". Coral Reefs. 26 (4): 1047–056. Bibcode:2007CorRe..26.1047C. doi:10.1007/s00338-007-0235-9. S2CID 39073111.

- Harary, David. "Joint-Value Creation Between Marine Protected Areas and the Private Sector" (PDF). thinkcds.org. Center for Development and Strategy. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Noone, Greg (22 December 2021). "How Marine Protected Areas Can Pay for Their Own Protection". Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- "Marine Protected Area Networks". Unep-Wcmc. 2011-01-18. Archived from the original on 2011-12-20. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "Asinara Natural Marine Reserve". Protectedplanet.net. Archived from the original on 2012-06-08. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Engaging marine scientists and fishers to share knowledge and perceptions – An overview. Briand, F., Gourguet, S. et al. Dec. 2018.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329810761_Engaging_marine_scientists_and_fishers_to_share_knowledge_and_perceptions_-_An_overview

- Lowry, G. K.; White, A. T.; Christie, P. (2009). "Scaling Up to Networks of Marine Protected Areas in the Philippines: Biophysical, Legal, Institutional, and Social Considerations". Coastal Management. 37 (3): 274–90. doi:10.1080/08920750902851146. S2CID 53701615.

- "Ocean Governance: Who Owns the Ocean? | Heinrich Böll Stiftung". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- Wells et al. 2008, p. 13

- Wells, S. (23 May 2018). National and Regional Networks of Marine Protected Areas: A Review of Progress. UNEP-WCMC / UNEP. ISBN 9789280729757 – via Internet Archive.

- "Bunaken Marine Park". Protectedplanet.net. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Decision VII/28". Cbd.int. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Decision VII/15". Cbd.int. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "The World Has Two Years to Meet Marine Protection Goal. Can It Be Done?".

- Sala, Enric; Lubchenco, Jane; Grorud-Colvert, Kirsten; Novelli, Catherine; Roberts, Callum; Sumaila, U. Rashid (2018). "Assessing real progress towards effective ocean protection". Marine Policy. 91: 11–13. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.02.004.

- "Protection of the South Orkney Islands southern shelf". www.ccamlr.org. Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "CCAMLR to create world's largest Marine Protected Area". Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. 29 October 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- Wells et al. 2008, p. 15

- "Reaching marine conservation targets". Government of Canada. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- "Irish marine protected areas". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- https://www.gov.im/media/1346374/biodiversity-strategy-2015-final-version.pdf

- Kuempel, Caitlin; Jones, Kendall; Watson, James; Possingham, James (27 May 2017). "Quantifying biases in marine-protected-area placement relative to abatable threats". Conservation Biology. 33 (6): 1350–1359. doi:10.1111/cobi.13340. PMC 6899811. PMID 31131932.

- "Global Ocean Protection: Present Status and Future Possibilities". Iucn.org. 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "UN (2010) Millennium Development Goals Report – Addendum". Mdgs.un.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-27. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Christie, Patrick, and A.T White. "Best practices for improved governance of coral reef marine protected areas." (2007): 1048-1056. Print.

- Halpern, B. (2003). "The impact of marine reserves: do reserves work and does reserve size matter?". Ecological Applications. 13: 117–137. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0117:TIOMRD]2.0.CO;2.

- "No Take Areas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2012.

- Mora, C; Sale, P (2011). "Ongoing global biodiversity loss and the need to move beyond protected areas: A review of the technical and practical shortcoming of protected areas on land and sea" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 434: 251–266. Bibcode:2011MEPS..434..251M. doi:10.3354/meps09214.

- Wooda, Louisa J.; Fisha, Lucy; Laughrena, Josh; Pauly, Daniel (2008). "Assessing Progress Towards Global Marine Protection Targets: Shortfalls in Information and Action". Oryx. 42 (3): 340–351. doi:10.1017/S003060530800046X.

- "Protecting the ocean". www.marineprotectedareas.org.za. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Marine Protected Areas". www.saambr.org.za. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Mann-Lang, Judy; Mann, Bruce; Sink, Kerry, eds. (September 2018). "Fact sheet 3: Marine Protected Areas" (PDF). SAAMBR. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Marine Protected Areas and South Africa: Key takeaways" (PDF). www.nairobiconvention.org. WIOSAP Project. 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- Fielding, P. (2021). Marine & Coastal Areas under Protection: Republic of South Africa (PDF). UNEP-Nairobi Convention and WIOMSA. 2021. Western Indian Ocean Marine Protected Areas Outlook: Towards achievement of the Global Biodiversity Framework Targets. (Report). Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP and WIOMSA. pp. 133–166. ISBN 978-9976-5619-0-6.

- Wells et al. 2008, p. 33

- Hu, Wenjia; Liu, Jie; Ma, Zhiyuan; Wang, Yuyu; Zhang, Dian; Yu, Weiwei; Chen, Bin (2020). "China's marine protected area system: Evolution, challenges, and new prospects". Marine Policy. 115: 103780. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103780. ISSN 0308-597X. S2CID 214281593.

- Li, Yunzhou; Fluharty, David L. (2017). "Marine protected area networks in China: Challenges and prospects". Marine Policy. 85: 8–16. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.08.001. ISSN 0308-597X.

- Ma, Chun; Zhang, Xiaochun; Chen, Weiping; Zhang, Guangyu; Duan, Huihui; Ju, Meiting; Li, Hongyuan; Yang, Zhihong (2013). "China's special marine protected area policy: Trade-off between economic development and marine conservation". Ocean & Coastal Management. 76: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.02.007. ISSN 0964-5691.

- "Summary Report for MPAs in the Philippines" (PDF). reefbase.org.

- Wells et al. 2008

- HP Foundation (2018) Mexico Marine Strategy 2018-2021

- Kirlin, John; Caldwell, Meg; Gleason, Mary; Weber, Mike; Ugoretz, John; Fox, Evan; Miller-Henson, Melissa (2013-03-01). "California's Marine Life Protection Act Initiative: Supporting implementation of legislation establishing a statewide network of marine protected areas". Ocean & Coastal Management. 74: 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.08.015. ISSN 0964-5691.

- "Seychelles starts 'Britain-sized' reserve". BBC News. 22 February 2018.

- "Seychelles designates huge new marine reserve". phys.org.

- "New Australian Marine Parks Protect an Area Twice the Size of the Great Barrier Reef". Mongabay. Ecowatch. 14 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- "Global launch of the Great Blue Wall". IUCN. 10 November 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Malavika Vyawahare (6 January 2022). "'Great Blue Wall' aims to ward off looming threats to western Indian Ocean". Mongabay. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Marine Protected Areas Conserve Mediterranean Red Coral". Science Daily. May 11, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- Marine Peace Parks in the Mediterranean. 2011. Briand, F. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239940856_Marine_Peace_Parks_in_the_Mediterranean

- "The association – MedPAN".

- "The Mediterranean needs more marine reserves – they are an antidote to the crisis, says WWF". www.wwfmmi.org.

- Marine life worse off inside 'protected' areas, analysis reveals The Guardian, 2019

- "Marine Protected Areas 2020: Building Efective Conservation Networks" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Supertrawlers 'making a mockery' of UK's protected seas". TheGuardian.com. 11 June 2020.

- "Marine Protected Areas around the UK". The Wildlife Trusts. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Protecting and sustainably using the marine environment". UK Government. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Map". UK Marine Protected Areas Centre. Retrieved 19 March 2015."Marine Protected Areas in the UK". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Webster, Ben (8 June 2020). "Sea fishing banned under plan to protect nation's marine life". The Times. No. 73, 180. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- "Conservationists call for UK to create world's largest marine reserve". The Guardian. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "The Blue Belt programme". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- "Chagos Marine Reserve, British Indian Ocean Territory". Marine Reserves Coalition. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Chagos Marine Reserve". Chagos Conservation Trust. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "World's Largest Single Marine Reserve Created in Pacific". National Geographic. World’s Largest Single Marine Reserve Created in Pacific. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Pitcairn Islands get huge marine reserve". BBC. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015."Pitcairn Islands to get world's largest single marine reserve". The Guardian. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Ascension Island to become marine reserve". BBC. 3 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- Grundy, Richard. "Tristan's Marine Protection Zone Announced". www.tristandc.com. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- "UK Overseas Territory becomes one of the world's biggest sanctuaries for wildlife". The RSPB. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- "Conservation International – World's Largest Marine Protected Area Created in Pacific Ocean". Conservation.org. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Smith & Miller 2003.

- North Sea Marine Cluster. "Managing Marine Protected Areas" (PDF). NSMC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- "Marine protected areas % of territorial waters". The World Bank. 2016–2017. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- "Marine Protected Areas Government Website". Mpa.gov. 2012-05-07. Archived from the original on 2012-06-06. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Berezansky, L.; Idels, L.; Kipnis, M. (2011). "Mathematical model of marine protected areas". IMA Journal of Applied Mathematics. 76 (2): 312–325. doi:10.1093/imamat/hxq043. hdl:10613/2741. ISSN 0272-4960. Preprint: http://hdl.handle.net/10613/2741.

- Yamahara, Kevan M.; Preston, Christina M.; Birch, James; Walz, Kristine; Marin, Roman; Jensen, Scott; Pargett, Douglas; Roman, Brent; Ussler, William; Zhang, Yanwu; Ryan, John; Hobson, Brett; Kieft, Brian; Raanan, Ben; Goodwin, Kelly D.; Chavez, Francisco P.; Scholin, Christopher (2019). "In situ Autonomous Acquisition and Preservation of Marine Environmental DNA Using an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle". Frontiers in Marine Science. 6: 373. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00373. ISSN 2296-7745.

- Dinerstein, E.; Vynne, C.; Sala, E.; Joshi, A. R.; Fernando, S.; Lovejoy, T. E.; Mayorga, J.; Olson, D.; Asner, G. P.; Baillie, J. E. M.; Burgess, N. D.; Burkart, K.; Noss, R. F.; Zhang, Y. P.; Baccini, A.; Birch, T.; Hahn, N.; Joppa, L. N.; Wikramanayake, E. (2019). "A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets". Science Advances. 5 (4): eaaw2869. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.2869D. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw2869. PMC 6474764. PMID 31016243.

- "Improving ocean protection with the first marine protected areas guide". Institut de Recherche pour le Développement. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- Grorud-Colvert, Kirsten; Sullivan-Stack, Jenna; Roberts, Callum; Constant, Vanessa; Horta e Costa, Barbara; Pike, Elizabeth P.; Kingston, Naomi; Laffoley, Dan; Sala, Enric; Claudet, Joachim; Friedlander, Alan M.; Gill, David A.; Lester, Sarah E.; Day, Jon C.; Gonçalves, Emanuel J.; Ahmadia, Gabby N.; Rand, Matt; Villagomez, Angelo; Ban, Natalie C.; Gurney, Georgina G.; Spalding, Ana K.; Bennett, Nathan J.; Briggs, Johnny; Morgan, Lance E.; Moffitt, Russell; Deguignet, Marine; Pikitch, Ellen K.; Darling, Emily S.; Jessen, Sabine; Hameed, Sarah O.; Di Carlo, Giuseppe; Guidetti, Paolo; Harris, Jean M.; Torre, Jorge; Kizilkaya, Zafer; Agardy, Tundi; Cury, Philippe; Shah, Nirmal J.; Sack, Karen; Cao, Ling; Fernandez, Miriam; Lubchenco, Jane (2021). "The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean" (PDF). Science. 373 (6560): eabf0861. doi:10.1126/science.abf0861. PMID 34516798. S2CID 237473020.

- Pandolfi, J.M.; et al. (2003). "Global trajectories of long-term decline of coral reef ecosystems". Science. 301 (5635): 955–958. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..955P. doi:10.1126/science.1085706. PMID 12920296. S2CID 31903371.

- Hughes, T.P.; et al. (2003). "Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs". Science. 301 (5635): 929–933. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..929H. doi:10.1126/science.1085046. PMID 12920289. S2CID 1521635.

- Mora C.; Andrèfouët, S; Costello, M. J.; Kranenburg, C; Rollo, A; Veron, J; Gaston, K. J.; Myers, R. A.; et al. (2006). "Coral reefs and the global network of Marine Protected Areas" (PDF). Science. 312 (5781): 1750–1751. doi:10.1126/science.1125295. PMID 16794065. S2CID 13067277.

- "Marine Protected Areas (Innri)" (PDF). unuftp.is.

- Warne, Kennedy. "Saving the Sea's Bounty"] National Geographic. April 2007.

- MPA News, Vol. 6 No. 1, July 2004

- Wells et al. 2008, p. 17

The International Union for Conservation of Nature defines a protected area as:

"A clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated, and managed, through legal or effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem service and cultural value."

- Archived February 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "WikiLeaks reveals U.S., British use marine reserves as tool of imperialism". Embassy London. 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- Bruno, John F.; Bates, Amanda E.; Cacciapaglia, Chris; Pike, Elizabeth P.; Amstrup, Steven C.; van Hooidonk, Ruben; Henson, Stephanie A.; Aronson, Richard B. (2018). "Climate change threatens the world's marine protected areas". Nature Climate Change. 8 (6): 499–503. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0149-2. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 89659925.

- McLeod, Elizabeth; Salm, Rodney; Green, Alison; Almany, Jeanine (2009). "Designing marine protected area networks to address the impacts of climate change". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 7 (7): 362–370. doi:10.1890/070211. ISSN 1540-9295.

- Soto, Cristina G. (2002). "The potential impacts of global climate change on marine protected areas". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 11 (3): 181–195. doi:10.1023/A:1020364409616. ISSN 1573-5184. S2CID 40966545.

- Wilson, Kristen L.; Tittensor, Derek P.; Worm, Boris; Lotze, Heike K. (2020). "Incorporating climate change adaptation into marine protected area planning". Global Change Biology. 26 (6): 3251–3267. doi:10.1111/gcb.15094. ISSN 1354-1013. PMID 32222010. S2CID 214694690.

- Roberts, Callum M.; O’Leary, Bethan C.; McCauley, Douglas J.; Cury, Philippe Maurice; Duarte, Carlos M.; Lubchenco, Jane; Pauly, Daniel; Sáenz-Arroyo, Andrea; Sumaila, Ussif Rashid; Wilson, Rod W.; Worm, Boris; Castilla, Juan Carlos (2017). "Marine reserves can mitigate and promote adaptation to climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (24): 6167–6175. doi:10.1073/pnas.1701262114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5474809. PMID 28584096.

- "Fines to rogue fishermen fall and illegal fishing escapes prosecution". The Ferret. 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2019-10-06.

Sources

- Wells, Sue; Sheppard, V.; van Lavieren, H.; Barnard, N.; Kershaw, F.; Corrigan, C.; Teleki, K.; Stock, P.; Adler, E. (2008). National and Regional Networks of Marine Protected Areas:A Review of Progress. Master Evaluation for the UN Effort. World Conservation Monitoring Centre The Americas. ISBN 9789280729757. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- Smith, D.; Miller, K.A. (2003). Norton, S.F. (ed.). "Safe Harbors for our Future: An Overview of Marine Protected Areas". Diving for Science. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (22nd Annual Scientific Diving Symposium). Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Australian Government, Department of the Environment and Water Resources (May 2007). Growing up strong: The first 10 years of Indigenous Protected Areas in Australia (PDF). Canberra: Australian Government. ISBN 978-0642553522. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

External links

Media related to Marine protected areas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marine protected areas at Wikimedia Commons- Marine Protected Areas by Project Regeneration

- Marine Protection Atlas - an online tool from the Marine Conservation Institute that provides information on the world's protected areas and global MPA campaigns. Information comes from a variety of sources, including the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), and many regional and national databases.

- Marine protected areas - viewable via Protected Planet, an online interactive search engine hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC).