Black caiman

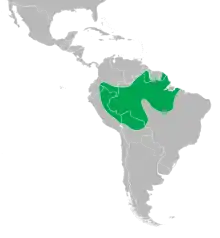

The black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) is a species of large crocodilian and is the largest species of the family Alligatoridae. It is a carnivorous reptile that lives along slow-moving rivers, lakes, seasonally flooded savannas of the Amazon basin, and in other freshwater habitats of South America. It is a large species, growing to at least 5 m (16 ft) and possibly up to 6 m (20 ft) in length, which makes it the third largest reptile in the Neotropical realm, behind the American crocodile, and the Orinoco crocodile.[6][7][8] As its common and scientific names imply, the black caiman has a dark coloration as an adult. In some individuals, the dark coloration can appear almost black. It has grey to brown banding on the lower jaw. Juveniles have a more vibrant coloration compared to adults with prominent white to pale yellow banding on the flanks that remains present well into adulthood, at least more when compared to other species. The morphology is quite different from other caimans but the bony ridge that occurs in other caimans is present. The head is large and heavy, an advantage in catching larger prey. Like all crocodile-like animals, caimans are long, squat creatures, with big jaws, long tails and short legs. They have thick, scaled skin, and their eyes and noses are located on the tops of their heads. This enables them to see and breathe while the rest of their bodies are underwater.

| Black caiman Temporal range: Present, | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| |

| Adult above, juvenile below | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Subfamily: | Caimaninae |

| Clade: | Jacarea |

| Genus: | Melanosuchus |

| Species: | M. niger |

| Binomial name | |

| Melanosuchus niger (Spix, 1825) | |

| |

| Synonyms[4][5] | |

| |

The black caiman is the second largest known predator in the Amazon ecosystem, after the Orinoco crocodile, preying on a variety of fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals.[7] It is a generalist and apex predator, potentially capable of taking any animal within its range, including other predators.[9] Few ecological studies have been carried out on the species, but the black caiman has its own ecological niche that enables coexistence without too much competition. As the largest predator in the ecosystem, it may also be a keystone species, playing an important role of maintaining the structure of the ecosystem.[7] Reproduction takes place in the dry season. Females build a nest mound with an egg chamber, protecting the eggs from predators. Hatchlings form groups called pods, guarded by the presence of the female. These pods may contain individuals from other nests. Once common, it was hunted to near extinction primarily for its commercially valuable hide. It is now making a comeback, listed as Conservation Dependent.[2] Overall a little-known species, it was not researched in any detail until the 1980s, when the leather-trade had already taken its toll.[10] It is a dangerous species to humans, and attacks have occurred in the past.[11]

Characteristics

The black caiman has dark-coloured, scaly skin. The skin coloration helps with camouflage during its nocturnal hunts, but may also help absorb heat (see thermoregulation). The lower jaw has grey banding (brown in older animals), and pale yellow or white bands are present across the flanks of the body, although these are much more prominent in juveniles. This banding fades only gradually as the animal matures. The bony ridge extending from above the eyes down the snout, as seen in other caiman, is present. The eyes are large, as befits its largely nocturnal activity, and brown in colour. Mothers on guard near their nests are tormented by blood-sucking flies that gather around their vulnerable eyes, leaving them bloodshot.

The black caiman is structurally dissimilar to other caiman species, particularly in the shape of the skull. Compared to other caimans, it has distinctly larger eyes. Although the snout is relatively narrow, the skull (given the species' considerably larger size) is much larger overall than other caimans. Black caimans are relatively more robust than other crocodilians of comparable length. There appears to be varying skull morphology in this species depending on the age and particular individual animal, which is not uncommon in other modern crocodilians, and by gender, with adult males typically having much more massive skulls relative to their size than like-age females. Due to the differences, males have a stronger bite force and likely exploit a different, and larger, prey base than females.[12] Young black caiman can be distinguished from large spectacled caimans by their proportionately larger head, as well as by the colour of the jaw, which is light coloured in the spectacled caiman and dark with three black spots in the black caiman.[10]

Size

The black caiman is one of the largest extant reptiles. It is the largest predator in the Amazon basin, and also potentially the largest member of the family Alligatoridae. It is also significantly larger than other caiman species. Most adult black caimans are 2.2 to 4.3 m (7 ft 3 in to 14 ft 1 in) in length, with a few old males exceeding 5 m (16 ft 5 in). Sub-adult male specimens of around 2.5–3.4 m (8 ft 2 in – 11 ft 2 in) will weigh roughly 95–125 kg (209–276 lb), around the same size as a mature female, but will quickly increase in bulk and weight. The average size of adult females at their nests was found to be 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in).[13] Mid-sized mature males of 3.5–4 m (11 ft 6 in – 13 ft 1 in) weigh approximately 300 kg (660 lb), while larger male specimens reach weights of more than 400 kg (880 lb), possibly up to 600 kg (1,300 lb), being relatively bulky crocodilians.[14][15][16] A relatively small adult male of a total length of 3.4 m (11 ft 2 in) weighed 98 kg (216 lb) while an adult male considered fairly large at a length of 4.2 m (13 ft 9 in) weighed approximately 350 kg (770 lb).[15][17] Another sampling of subadult males found them to range in length from 2.1 to 2.8 m (6 ft 11 in to 9 ft 2 in), averaging 2.45 m (8 ft 0 in), and that they weighed from 26 to 86 kg (57 to 190 lb), averaging 48 kg (106 lb).[18] In some areas (such as the Araguaia River) this species is consistently reported at 4 to 5 m (13 ft 1 in – 16 ft 5 in) in length, although specimens this size are uncommon. Several widely reported but unconfirmed (and probably largely anecdotal) reports claim that the black caiman can grow to over 6.1 m (20 ft 0 in) in length and weigh up to 1,100 kg (2,400 lb).[9][10][19] While it is unclear what the sources for this maximum size are, many scientific papers accept that this species can attain extreme sizes as such.[20][21][22] In South America, two other crocodilians reportedly reach similar sizes: the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) and the Orinoco crocodile (C. intermedius).

Biology and behaviour

Hunting and diet

Black caimans are apex predators with a generalist diet, and can take virtually any terrestrial and riparian animal found throughout their range. Similar to other large crocodilians, black caimans have even been observed catching and eating smaller species, such as the spectacled caiman and sometimes cannibalizing smaller individuals of their own kind. Hatchlings mostly eat small fish, frogs, and invertebrates such as crustaceans and insects, but with time and size graduate to eating larger fish, including piranhas, catfish, and perch, which remain a significant food source for all black caimans. Dietary studies have focused on young caimans (due both to their often being more common than large adults and to their being easier to handle), the largest specimen examined for stomach contents in one study being only 1.54 m (5.1 ft) notably under sexually mature size, which is at a minimum 2 m (6.6 ft) in smaller females. Although diverse prey is known to be captured by young black caimans, dietary studies have shown snails often dominate the diet of young caiman, followed by quite small fish.[23][24][25][26] Fish were the main prey of black caimans of over subadult size in Manú National Park, Peru.[27] Various prey will be taken by availability, includes snakes, turtles, birds and mammals, the latter two mainly when they come to drink at the river banks. Mammalian prey mostly include common Amazonian species such as various monkeys, sloths, armadillos, pacas, agoutis, coatis, and capybaras. Large prey can include other species of caiman, deer, peccaries, tapirs, anacondas, giant otters,[28] and domestic animals including pigs, cattle, horses, and dogs. Although rare predations on cougars or even jaguars have been reported,[29] very little evidence exists of such predation, and cats are likely to avoid ponds with large adult black caimans, suggesting that adults of this species are higher in the food chain than even the jaguar.[30][31] Where capybara and white-lipped peccary herds are common, they are reportedly among the most common prey item for large adults.[32][33] Evidence has suggested fairly large river turtles can be counted among the prey of adult black caimans, the bite force of which is apparently sufficient to shatter a turtle shell.[34] Scars on Amazon river dolphins suggest they may occasionally be attacked by black caimans.[35] Large males have even been observed to cannibalize other Black Caimans.[36] Compared to the smaller caiman species, the black caiman more often hunts terrestrially at night, using its acute hearing and sight.[10] As with all crocodilian species, their teeth are designed to grab but not chew, so they generally try to swallow their food whole after drowning or crushing it. Large prey that cannot be swallowed whole are often stored so that the flesh will rot enough to allow the caiman to take bites out of the flesh.

Reproduction

At the end of the dry season, females build a nest of soil and vegetation, which is about 1.5 meters (4.9 feet) across and 0.75 meters (2.5 feet) wide. They lay up to 65 eggs (though usually somewhere between 30 and 60), which hatch in about six weeks, at the beginning of the wet season, when newly flooded marshes provide ideal habitat for the juveniles once hatched.[10] The eggs are quite large, averaging 144 g (5.1 oz) in weight.[13] Unguarded clutches (when the mother goes off to hunt) are readily devoured by a wide array of animals, regularly including mammals such as South American coatis (Nasua nasua) or large rodents, egg-preying snakes and birds such as herons and vultures. Occasionally predators are caught and killed by the mother caiman.[10] Hatching is said to occur between 42 and 90 days after the eggs are laid.[10] It is well documented that, as with other crocodilians, caimans frequently move their young from the nest in their mouths after hatching (whence the erroneous belief that they eat their young), and transport them to a safe pool. The mother will assist chirping, unhatched young to break out of the leathery eggs, by delicately breaking the eggs between her teeth. She will try to look after her young for several months but the baby caimans are largely independent and most do not survive to maturity. Baby black caimans are subject to predation even more regularly after they hatch, facing many of the same mesopredators, as well any other crocodilian (including those of their own species), large snake or large, carnivorous fish that they encounter. Predation is so common that black caimans count on their young to survive via safety in numbers.[10] The female black caiman only breeds once every 2 to 3 years.

Interspecific predatory relationships

Many predators, including various fish, mammal, reptile and even amphibian species, feed on caiman eggs and hatchlings. The black caiman shares its habitat with at least 3 other semi-amphibious animals considered apex predators and is usually able to co-exist with them by focusing on different prey and micro-habitats. These are giant otters which are social and are obligate aquatic foragers and piscivorans, green anacondas which are slow, infrequent feeders mostly on medium-sized mammals and reptiles, and jaguars, which are the most terrestrial of these and focus their diet mainly on relatively larger mammals and reptiles. Black caimans eat more or less all the same prey as the other species. They are possibly the most opportunistic but, despite being the largest predator of the area, can metabolically live off of their food longer and thus may not need to hunt as frequently. Usually, each predator avoids encounters with adults of the others but battles, which can be lost by nearly any side, may rarely occur. More so than even otters and anaconda, jaguars and black caiman arguably sit atop this food chain. Once the black caiman attains a length of a few feet, it has few natural predators. Large anacondas may take an occasional young caiman of this species. The jaguar (Panthera onca), being a known predator of all other caiman species, is the only primary predatory threat to juvenile and subadult black caimans, with several records of predation on young black caimans and eggs. Adult black caimans have no natural predators, as is true of other similarly-sized crocodilian species given the size, weight, bite force, thick hide, and immense strength; in rare instances, they even may themselves prey upon jaguars.[37][38][39]

Conservation status and threats

Humans hunt black caimans for leather or meat. This species was classified as Endangered in the 1970s due to the high demand for its well-marked skin. The trade in black caiman leather peaked from the 1950s to 1970s, when the smaller but much more common spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) became the more commonly hunted species. Local people still trade black caiman skins and meat today at a small scale but the species has rebounded overall from the overhunting in the past.[13] That black caimans lay, on average, around 40 eggs has helped them recover to some degree.[13] Perhaps an equal continuing threat is habitat destruction, since development and clear-cutting is now epidemic in South America. Spectacled caimans have now filled the niche of crocodilian predator of fish in many areas. Due to their greater numbers and faster reproductive abilities, the Spectacled populations are locally outcompeting black caimans, although the larger species dominates in a one-on-one basis.[10] Persistent management is needed to control caiman-hunting and is quite difficult to enforce effectively.[13] After the depletion of the black caiman population, piranhas and capybaras, having lost perhaps their primary predator, reached unnaturally high numbers. This has, in turn, led to increased agricultural and livestock losses.[10]

Compounding the conservation issues it faces, this species occasionally preys on humans.[40] Most tales are poorly documented and unconfirmed but, given this species' formidable size and strength, attacks on humans are quite often fatal.[17][11][41]

The species is uncommon in captivity and breeding it has proven to be a challenge. The first captive breeding outside its native range was at Aalborg Zoo in 2013.[42]

Notes

- Except the populations of Brazil and Ecuador which are included in Appendix II.

See also

- List of largest reptiles

References

- Rio, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D. (6 September 2021). "Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem". PeerJ. 9: e12094. doi:10.7717/peerj.12094. PMC 8428266. PMID 34567843.

- Ross JP (2000). "Melanosuchus niger". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T13053A3407604. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T13053A3407604.en.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Boulenger GA (1889). Catalogue of the Chelonians, Rhynchocephalians, and Crocodiles in the British Museum (Natural History). New Edition. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). x + 311 pp. + Plates I-III. (Caiman niger, pp. 292-293).

- "Melanosuchus niger ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger). Crocodilian Specialist Group. Retrieved on 2013-04-13.

- Melanosuchus niger Black caiman. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved on 2013-04-13.

- "Arkive closure". Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- Black Caiman, Black Caiman Skull. Dinosaurcorporation.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-23.

- Crocodilian Species – Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger). Crocodilian.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-23.

- Sideleau B, Britton ARC (2012). "A preliminary analysis of worldwide crocodilian attacks". pp. 111–114. In: Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 21st Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group, Manila, Philippines. IUCN. Gland, Switzerland, Manila, Philippines.

- Foth, C., Bona, P., & Desojo, J. B. (2015). Intraspecific variation in the skull morphology of the black caiman Melanosuchus niger (Alligatoridae, Caimaninae). Acta Zoologica, 96(1), 1-13.

- Thorbjarnarson JB (2010). "Black Caiman Melanosuchus niger ". pp. 29–39. In: Manolis SC, Stevenson C (editors). Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Third edition. Darwin: Crocodile Specialist Group. iucncsg.org

- French Guiana. kwata.net (2003).

- Da Silveira, R., Do Amaral, J.V., Mangusson, W.E. & Thorbjarnarson, J.B. (2011). Melanosuchus niger: Signaling Behavior & Long-Distance Movement. Herpetological Review, 42 (3): 424-425.

- Sirder, H. (2014). Le Caiman noir, Espèce transamazonienne. Livret édité par le Parc naturel régional de la Guyane dans le cadre du programme OYAN, Parque nacional Cabo Orange.

- Haddad V Jr, Fonseca WC (2011). "A fatal attack on a child by a black caiman (Melanosuchus niger)". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 22 (1): 62–64. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2010.11.010. PMID 21377122.

- Cardoso AM, De Souza AJ, Menezes RC, Pereira WL, Tortelly R (2013). "Gastric Lesions in Free-Ranging Black Caimans (Melanosuchus niger) Associated With Brevimulticaecum Species". Veterinary Pathology. 50 (4): 582–4. doi:10.1177/0300985812459337. PMID 22961885. S2CID 206510179.

- Johnson, C., Anderson, S., Dallimore, J., Winser, S., & Warrell, D. A. (2008). Oxford handbook of expedition and wilderness medicine. OUP Oxford.

- Da Silveira, R., Magnusson, W. E., & Campos, Z. (1997). Monitoring the distribution, abundance and breeding areas of Caiman crocodilus crocodilus and Melanosuchus niger in the Anavilhanas Archipelago, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Journal of Herpetology, 514-520.

- Barker, G. M. (Ed.). (2004). Natural enemies of terrestrial molluscs. CABI.

- Junk, W. J., & da Silva, V. M. F. (1997). Mammals, reptiles and amphibians. In The Central Amazon Floodplain (pp. 409-417). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Horna JV, Cintra R, Ruesta PV (2001). "Feeding ecology of black caiman Melanosuchus niger in a western Amazonian forest: The effects of ontogeny and seasonality on diet composition". Ecotropica. 7: 1–11.

- Horna V, Zimmermann R, Cintra R, Vásquez P, Horna J (2003). "Feeding ecology of the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) in Manu National Park, Peru". Lyonia. 4: 65–72.

- Marioni B, Da Silveira R, Magnusson WE, Thorbjarnarson J (2008). "Feeding behavior of two sympatric caiman species, Melanosuchus niger and Caiman crocodilus, in the Brazilian Amazon". Journal of Herpetology. 42 (4): 768–772. doi:10.1670/07-306R1.1. S2CID 55729396.

- Reynolds N (2008). Dietary competition between the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) and the spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) within the Lago Preto Reserve, Peru. DI512 Dissertation.

- Wright, L. (1982). The IUCN Amphibia-Reptilia red data book (Vol. 1). IUCN.

- Hunter, Luke (2011) Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691152288.

- "Jaguar Found Inside the Big Black Caiman". YouTube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- Black Caiman – AC Tropical Fish.

- Black Caiman. Adapting Eden. Retrieved on 2015-09-25.

- Potts, Ryan J. "Endangered Reptiles and Amphibians of the World – II. The Black Caiman, Melanosuchus niger ". Vermont Herpetology.

- Foth C, Bona P, Desojo JB (2015). "Intraspecific variation in the skull morphology of the black caiman Melanosuchus niger (Alligatoridae, Caimaninae)". Acta Zoologica. 96 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1111/azo.12045.

- de la Ossa J, Vogt RC, Ferrara CR (2010). "Melanosuchus niger (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae) as opportunistic turtle consumer in its natural environment". Revista Colombiana de Ciencia Animal. 2 (2): 244–252. doi:10.24188/recia.v2.n2.2010.268.

- Martin AR, Da Silva VM (2006). "Sexual dimorphism and body scarring in the boto (Amazon river dolphin) Inia geoffrensis". Marine Mammal Science. 22 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00003.x.

- Rosenblatt, Adam (November 15, 2021). "What do adult black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) actually eat?". Biotropica. 54 (1).

- Da Silveira, Ronis; Ramalho, Emiliano E.; Thorbjarnarson, John B.; Magnusson, William E. (2010). "Depredation by Jaguars on Caimans and Importance of Reptiles in the Diet of Jaguar". Journal of Herpetology. 44 (3): 418–424. doi:10.1670/08-340.1. S2CID 86825708.

- Somaweera, R., Brien, M., & Shine, R. (2013). The role of predation in shaping crocodilian natural history. Herpetological Monographs, 27(1), 23-51.

- Chinery, M. (2000). Predators and Prey. Cherrytree Books.

- Jornal Hoje – Bióloga atacada por jacaré na Amazônia luta pela preservação da espécie. G1.globo.com (2010-08-04). Retrieved on 2013-01-11. (in Portuguese).

- Welcome To The Official Mark O'Shea Website. Markoshea.tv. Retrieved on 2012-08-23.

- TV2 Nord (12 September 2013). Sjældne kaimanunger kan nu ses af publikum. Retrieved 23 April 2017. (in Danish).

Further reading

- Spix JB (1825). Animalia nova sive species novae lacertarum, quas in itinere per Brasiliam annis MDCCCXVII – MDCCCXX jussu et auspiciis Maximiliani Josephi I. Bavariae Regis suscepto collegit et descripsit. Munich: F.S. Hübschmann. Index (4 unnumbered pages) + 26 pp. + 30 color plates. (Caiman niger, new species, pp. 3-4 + Plate IV). (in Latin).

External links

- The Night of the Caimans, from International Wildlife Federation.