Merino

The Merino is a breed or group of breeds of domestic sheep, characterised by very fine soft wool. It was established in Spain near the end of the Middle Ages, and was for several centuries kept as a strict Spanish monopoly; exports of the breed were not allowed, and those who tried risked the death penalty. During the eighteenth century, flocks were sent to the courts of a number of European countries, including France (where they developed into the Rambouillet), Hungary, the Netherlands, Prussia, Saxony and Sweden. The Merino subsequently spread to many parts of the world, including South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. Numerous recognised breeds, strains and variants have developed from the original type; these include, among others, the American Merino and Delaine Merino in the Americas, the Australian Merino, Booroola Merino and Peppin Merino in Oceania, the Gentile di Puglia, Merinolandschaf and Rambouillet in Europe.[1]: 861

The Australian Poll Merino is a polled (hornless) variant. Rams of other Merino breeds have long, spiral horns which grow close to the head, while ewes are usually hornless.

History

Etymology

The name merino was not documented in Spain until the early 15th century, and its origin is disputed.[2]

Two suggested origins for the Spanish word merino are given in:[3]

- It may be an adaptation to the sheep of the name of a Leonese official inspector (merino) over a merindad, who may have also inspected sheep pastures. This word is from the medieval Latin maiorinus, a steward or head official of a village, from maior, meaning "greater". However, there is no indication in any of the Leonese or Castilian law codes that this official, either named as maiorinus or merino had any duties connected with sheep, and the late date at which merino was first documented makes any connection with the name of an early mediaeval magistrate implausible.[4]

- It also may be from the name of an Imazighen tribe, the Marini (or in Spanish, Benimerines), who occupied parts of the southwest of the Iberian peninsula during the 12th and 13th centuries. This view gains some support from the derivation of many mediaeval Spanish pastoral terms from Arabic or Berber languages.[5] However, an etymology based on a 12th-century origin for Merino sheep when the Marinids were in Spain is unacceptable; the origin of the breed occurred much later.[6]

Origin

The three theories of the origins of the Merino breed in Spain are: the importation of north African flocks in the 12th century;[7] its origin and improvement in Extremadura in the 12th and 13th centuries;[8] the selective crossbreeding of Spanish ewes with imported rams at several different periods, so that its characteristic fine wool was not fully developed until the 15th century or even later.[9] The first theory accepts that the breed was improved by later importation of north African rams and the second accepts an initial stock of north African sheep related to types from Asia Minor, and both claim an early date and largely north African origin for the merino breed.[10]

Sheep were relatively unimportant in the Islamic Caliphate of Córdoba, and there is no record of extensive transhumance before the caliphate's fall in the 1030s. The Marinids, when a nomadic Zenata Berber tribe, held extensive sheep flocks in what is now Morocco, and its leaders who formed the Marinid Sultanate militarily intervened in southern Spain, supporting the Emirate of Granada several times in the late 13th and early 14th centuries.[11][12] Although they may possibly have brought new breeds of sheep into Spain,[13] there is no definite evidence that the Marinids did bring extensive flocks to Spain. As the Marinids arrived as an intervening military force, they were hardly in a position to protect extensive flocks and practice selective breeding.[14]

The third theory, that the Merino breed was created in Spain over several centuries with a strong Spanish heritage, rather than simply being an existing north African strain that was imported in the 12th century, is supported both by recent genetic studies and the absence of definitely merino wool before the 15th century. The predominant native sheep breed in Spain from pre-Roman times was the churro, a homogeneous group closely related to European sheep types north of the Pyrenees and bred mainly for meat and milk, with coarse, coloured wool. Churro wool had little value, except where its ewes had been crossed with a fine wool breed from southern Italy in Roman times.[15] Genetic studies have shown that the Merino breed most probably developed by the crossing of churro ewes with a variety of rams of other breeds at different periods, including Italian rams in Roman times, north African rams in the mediaeval period, and English rams from fine-wool breeds in the 15th century.[16][17]

Although Spain exported wool to England, the Low Countries and Italy in the 13th and 14th centuries this was only used to make cheap cloths. The earliest evidence of fine Spanish wool exports were to Italy in the 1390s and Flanders in the 1420s, although in both cases fine English wool was preferred. Spain became noted for its fine wool (spinning count between 60s and 64s) in the late 15th century, and by the mid-16th century its merino wool was acknowledged to equal that of the finest English wools.[18][19]

The earliest documentary evidence for merino wools in Italy dates to the 1400s, and in the 1420s and 1430s, merino wools were being mixed with fine English wool in some towns in the Low Countries to produce high quality cloth.[20][21] However, it was only in the mid-16th century that the most expensive grades of cloth could be made entirely from merino wool, after its quality had improved to equal that of the finest English wools, which were in increasingly short supply at that time.[22]

Preserved mediaeval woollen fabrics from the Low Countries show that, before the 16th century, only the best quality English wools had a fineness of staple comparable to modern merino wool. The wide range of Spanish wools produced in 13th and early 14th centuries were mostly used domestically for cheap, coarse and light fabrics, and were not merino wools.[23] Later in the 14th century, similar non-merino wools were exported from the northern Castilian ports of San Sebastián, Santander, and Bilbao to England and the Low Countries to make coarse, cheap cloth.[24][25] The quality of Spanish wools exported increased markedly in the late 15th century, as did their price, promoted by the efforts of the monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella to improve quality.[26][27]

Spain built up a virtual monopoly in fine wool exports in the final decades of the 15th century and in the 16th century, creating a substantial source of income for Castile.[28] In part, this was because most English wool was woven and made into textile goods within England by the 16th century, rather than being exported.[29]

Many of the Castillian merino flocks were owned by nobility or the church, although Alfonso X realised that granting the urban elites of the towns of Old Castile and León transhumant rights to would create an additional source of royal income and counteract the power of the privileged orders[30] During the late 15th, 16th and early 17th century, two-thirds of the sheep migrating annually were held in flocks of less than 100 sheep and very few flocks exceeded 1,000 sheep. By the 18th century, there were fewer small owners, and several owners held flocks of more than 20,000 sheep, but owners of small to moderately-sized flocks remained, and the Mesta was never simply a combination of large owners.[31]

The transhumant sheep grazed the southern Spanish plains in winter and the northern highlands in summer. The annual migrations to and from Castile and León, where the sheep were owned and where they had summer pasturage, was organised and controlled by the Mesta along designated sheep-walks, or cañadas reales and arranged for suitable grazing, water and rest stops in these routes, and for shearing when the flocks started their return north.[32]

The three Merino strains that founded the world's Merino flocks are the Royal Escurial flocks, the Negretti and the Paula. Among Merino bloodlines stemming from Vermont in the US, three historical studs were highly important: Infantado, Montarcos and Aguires. In recent times, Merino and breeds deriving from Merino stocks have spread worldwide. However, there has been a substantial decline in the numbers of several European Merino breeds, which are now considered to be endangered breeds and are no longer the subject of genetic improvement. In Spain, there are now two populations, the commercial Merino flocks, most common in the province of Extremadura and an "historical" Spanish Merino strain, developed and conserved in a breeding centre near Cordoba. The commercial Merino flocks show considerable genetic diversity, probably because of their cross-breeding with non-Spanish Merino-derived breeds since the 1960s, to create a strain more suitable for meat production.[33] The historical Spanish strain, bred from animals selected from the main traditional Spanish genetic lines to ensure the conservation of a purebred lineage, exhibits signs of inbreeding.[34]

.jpg.webp)

Before the 18th century, the export of Merinos from Spain was a crime punishable by death. In the 18th century, small exportation of Merinos from Spain and local sheep were used as the foundation of Merino flocks in other countries. In 1723, some were exported to Sweden, but the first major consignment of Escurials was sent by Charles III of Spain to his cousin, Prince Xavier the Elector of Saxony, in 1765. Further exportation of Escurials to Saxony occurred in 1774, to Hungary in 1775 and to Prussia in 1786. Later in 1786, Louis XVI of France received 366 sheep selected from 10 different cañadas; these founded the stud at the Royal Farm at Rambouillet. In addition to the fine wool breeds mentioned, other breeds derived from Merino stocks were developed to produce mutton, including the French Ile de France and Berrichon du Cher breeds. Merino sheep were also sent to Eastern Europe where their breeding began in Hungary in 1774[35]

The Rambouillet stud enjoyed some undisclosed genetic development with some English long-wool genes contributing to the size and wool-type of the French sheep.[36] Through one ram in particular named Emperor – imported to Australia in 1860 by the Peppin brothers of Wanganella, New South Wales – the Rambouillet stud had an enormous influence on the development of the Australian Merino.

Sir Joseph Banks procured two rams and four ewes in 1787 by way of Portugal, and in 1792 purchased 40 Negrettis for King George III to found the royal flock at Kew. In 1808, 2000 Paulas were imported.

The King of Spain also gave some Escurials to the Dutch government in 1790; these thrived in the Dutch Cape Colony (South Africa). In 1788, John MacArthur, from the Clan Arthur (or MacArthur Clan) introduced Merinos to Australia from South Africa.

From 1765, the Germans in Saxony crossed the Spanish Merino with the Saxon sheep[37] to develop a dense, fine type of Merino (spinning count between 70s and 80s) adapted to its new environment. From 1778, the Saxon breeding center was operated in the Vorwerk Rennersdorf. It was administered from 1796 by Johann Gottfried Nake, who developed scientific crossing methods to further improve the Saxon Merino. By 1802, the region had four million Saxon Merino sheep, and was becoming the centre for stud Merino breeding, and German wool was considered to be the finest in the world.

In 1802, Colonel David Humphreys, United States Ambassador to Spain, introduced the Vermont strain into North America with an importation of 21 rams and 70 ewes from Portugal and a further importation of 100 Infantado Merinos in 1808. The British embargo on wool and wool clothing exports to the U.S. before the 1812 British/U.S. war led to a "Merino Craze", with William Jarvis of the Diplomatic Corps importing at least 3,500[38] sheep between 1809 and 1811 through Portugal.

The Napoleonic wars (1793–1813) almost destroyed the Spanish Merino industry. The old cabañas or flocks were dispersed or slaughtered. From 1810 onwards, the Merino scene shifted to Germany, the United States and Australia. Saxony lifted the export ban on living Merinos after the Napoleonic wars. Highly decorated Saxon sheep breeder Nake from Rennersdorf had established a private sheep farm in Kleindrebnitz in 1811, but ironically after the success of his sheep export to Australia and Russia, failed with his own undertaking.

United States Merinos

Merino sheep were introduced to Vermont in 1812. This ultimately resulted in a boom-bust cycle for wool, which reached a price of 57 cents/pound in 1835. By 1837, 1,000,000 sheep were in the state. The price of wool dropped to 25 cents/pound in the late 1840s. The state could not withstand more efficient competition from the other states, and sheep-raising in Vermont collapsed.[39] Many sheep farmers from Vermont migrated with their flocks to other parts of the United States.

Australian Merinos

Early history

About 70 native sheep, suitable only for mutton, survived the journey to Australia with the First Fleet, which arrived in late January 1788. A few months later, the flock had dwindled to just 28 ewes and one lamb.[40]

In 1797, Governor King, Colonel Patterson, Captain Waterhouse and Kent purchased sheep in Cape Town from the widow of Colonel Gordon, commander of the Dutch garrison. When Waterhouse landed in Sydney, he sold his sheep to Captain John MacArthur, Samuel Marsden and Captain William Cox.[41] Although the early origin of the Australian Merino breed involved different stocks from Cape Colony, England, Saxony, France and America and although different Merino strains are bred today in Australia, the Australian Merino populations are genetically similar and distinct from all other Merino populations, indicating a common history after they arrived in Australia.[42]

John and Elizabeth Macarthur

By 1810, Australia had 33,818 sheep.[43] John MacArthur (who had been sent back from Australia to England following a duel with Colonel Patterson) brought seven rams and one ewe from the first dispersal sale of King George III stud in 1804. The next year, MacArthur and the sheep returned to Australia, Macarthur to reunite with his wife Elizabeth, who had been developing their flock in his absence. Macarthur is considered the father of the Australian Merino industry; in the long term, however, his sheep had very little influence on the development of the Australian Merino.

Macarthur pioneered the introduction of Saxon Merinos with importation from the Electoral flock in 1812. The first Australian wool boom occurred in 1813, when the Great Dividing Range was crossed. During the 1820s, interest in Merino sheep increased. MacArthur showed and sold 39 rams in October 1820, grossing £510/16/5.[44] In 1823, at the first sheep show held in Australia, a gold medal was awarded to W. Riley ('Raby') for importing the most Saxons; W. Riley also imported cashmere goats into Australia.

Eliza and John Furlong

Two of Eliza Furlong's (sometimes spelt Forlong or Forlonge) children had died from consumption, and she was determined to protect her surviving two sons by living in a warm climate and finding them outdoor occupations. Her husband John, a Scottish businessman, had noticed wool from the Electorate of Saxony sold for much higher prices than wools from New South Wales. The family decided on sheep farming in Australia for their new business. In 1826, Eliza walked over 1,500 miles (2,400 km) through villages in Saxony and Prussia, selecting fine Saxon Merino sheep. Her sons, Andrew and William, studied sheep breeding and wool classing. The selected 100 sheep were driven (herded) to Hamburg and shipped to Hull. Thence, Eliza and her two sons walked them to Scotland for shipment to Australia. In Scotland, the new Australia Company, which was established in Britain, bought the first shipment, so Eliza repeated the journey twice more. Each time, she gathered a flock for her sons. The sons were sent to New South Wales, but were persuaded to stop in Tasmania with the sheep, where Eliza and her husband joined them.[45]

The Age in 1908 described Eliza Furlong as someone who had 'notably stimulated and largely helped to mould the prosperity of an entire state and her name deserved to live for all time in our history' (reprinted Wagga Wagga Daily Advertiser January 27, 1989).[46]

John Murray

There were nearly 2 million sheep in Australia by 1830, and by 1836, Australia had won the wool trade war with Germany, mainly because of Germany's preoccupation with fineness. German manufacturers commenced importing Australian wool in 1845.[47] In 1841, at Mount Crawford in South Australia, Murray established a flock of Camden-blood ewes mated to Tasmanian rams. To broaden the wool and give the animals some size, it is thought some English Leicester blood was introduced. The resultant sheep were the foundation of many South Australian strong wool studs. His brother Alexander Borthwick Murray was also a highly successful breeder of Merino sheep.[48]

The Peppin brothers

The Peppin brothers took a different approach to producing a hardier, longer-stapled, broader wool sheep. After purchasing Wanganella Station in the Riverina, they selected 200 station-bred ewes that thrived under local conditions and purchased 100 South Australian ewes bred at Cannally that were sired by an imported Rambouillet ram. The Peppin brothers mainly used Saxon and Rambouillet rams, importing four Rambouillet rams in 1860.[49] One of these, Emperor, cut an 11.4 lb (5.1 kg clean) wool clip. They ran some Lincoln ewes, but their introduction into the flock is undocumented. In 1865, George Merriman founded the fine wool Merino Ravensworth Stud, part of which is the Merryville Stud at Yass, New South Wales.[40]

Vermont merinos in Australia

In the 1880s, Vermont rams were imported into Australia from the U.S.; since many Australian stud men believed these sheep would improve wool cuts, their use spread rapidly. Unfortunately, the fleece weight was high, but the clean yield low, the greater grease content increased the risk of fly strike, they had lower uneven wool quality, and lower lambing percentages. Their introduction had a devastating effect on many famous fine-wool studs.

In 1889, while Australian studs were being devastated by the imported Vermont rams, several U.S. Merino breeders formed the Rambouillet Association to prevent the destruction of the Rambouillet line in the U.S. Today, an estimated 50% of the sheep on the U.S. western ranges are of Rambouillet blood.[38]

The federation drought (1901–1903) reduced the number of Australian sheep from 72 to 53 million and ended the Vermont era. The Peppin and Murray blood strain became dominant in the pastoral and wheat zones of Australia.

High price records

The world record price for a ram was A$450,000 for JC&S Lustre 53, which sold at the 1988 Merino ram sale at Adelaide, South Australia.[50] In 2008, an Australian Merino ewe was sold for A$14,000 at the Sheep Show and auction held at Dubbo, New South Wales.[51]

Events

The New England Merino Field Days, which display local studs, wool, and sheep, are held during January in even numbered years in and around the Walcha, New South Wales district.[52] The Annual Wool Fashion Awards, which showcase the use of Merino wool by fashion designers, are hosted by the city of Armidale, New South Wales in March each year.[53]

Animal welfare developments

In Australia, mulesing of Merino sheep is a common practice to reduce the incidence of flystrike. It has been attacked by animal rights and animal welfare activists, with PETA running a campaign against the practice in 2004. The PETA campaign targeted U.S. consumers by using graphic billboards in New York City. PETA threatened U.S. manufacturers with television advertisements showing their companies' support of mulesing. Fashion retailers including Abercrombie & Fitch Co., Gap Inc and Nordstrom and George (UK) stopped stocking Australian Merino wool products.[54]

New Zealand banned mulesing on 1 October 2018.[55]

Characteristics

Merino is an excellent forager and very adaptable. It is bred predominantly for its wool,[56] and its carcass size is generally smaller than that of sheep bred for meat. South African Meat Merino (SAMM), American Rambouillet and German Merinofleischschaf[57] have been bred to balance wool production and carcass quality.

Merino has been domesticated and bred in ways that would not allow them to survive well without regular shearing by their owners. They must be shorn at least once a year because their wool does not stop growing. If this is neglected, the overabundance of wool can cause heat stress, mobility issues, and even blindness.[58]

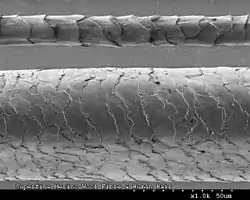

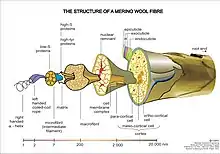

Wool qualities

Merino wool is fine and soft. Staples are commonly 65–100 mm (2.6–3.9 in) long. A Saxon Merino produces 3–6 kg (6.6–13.2 lb) of greasy wool a year, while a good quality Peppin Merino ram produces up to 18 kg (40 lb). Merino wool is generally less than 24 micron (μm) in diameter. Basic Merino types include: strong (broad) wool (23 - 24.5 μm), medium wool (21 - 22.9 μm), fine (18.6 - 20.9 μm), superfine (15 – 18.5 μm) and ultra-fine (11.5 - 15 μm).[59]

See also

- Arkhar-Merino

- Booroola Merino

- Delaine Merino

- Peppin Merino

- Poll Merino

- Rambouillet sheep

References

- Valerie Porter, Lawrence Alderson, Stephen J.G. Hall, D. Phillip Sponenberg (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding (sixth edition). Wallingford: CABI. ISBN 9781780647944.

- Rahn Phillips, C; Philips, W D Jnr. (1997). Spain's Golden Fleece: Wool Production and the Wool Trade from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780801855184.

- Corominas, Joan; Pascual, José A., eds. (1989). "Merino". Diccionario Crítico Etimológico Castellano e Hispánico. Vol. IV. Madrid: Gredos. ISBN 84-249-0066-9.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 3–4.

- Butzer K W (1988). "Cattle and Sheep from Old to New Spain: Historical Antecedents". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 78 (1): 29–56, at pages 39-40. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1988.tb00190.x.

- Sabatino Lopéz, C (1996). El origen de la oveja merina, Estudio 44. Ministerio de Agricultura y Pasca. pp. 123–4.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 4–5.

- Braudel, F; translated Reynolds, S (1995). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II: Volume I. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780520203082.

- Rahn Phillips, C; Philips, W D Jnr. (1997). Spain's Golden Fleece: Wool Production and the Wool Trade from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 40–1. ISBN 9780801855184.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 4, 34.

- Reilly, B F (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge University Press. pp. 162–3. ISBN 0521397413.

- Walker, M J (1983). "Laying a Mega-Myth: Dolmens and Drovers in Prehistoric Spain". World Archaeology. 15 (1): 37–50, at page 38. doi:10.1080/00438243.1983.9979883.

- Butzer K W (1988). "Cattle and Sheep from Old to New Spain: Historical Antecedents". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 78 (1): 39. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1988.tb00190.x.

- Sabatino Lopéz, C (1996). El origen de la oveja merina, Estudio 44. Ministerio de Agricultura y Pasca. p. 124.

- Ryder M L (1983). "A survey of European primitive breeds of sheep". Annales de Génétique et de Sélection Animale. 13 (4): 381–418, at pages 404, 414–5. doi:10.1186/1297-9686-13-4-381. PMC 2718014. PMID 22896215.

- Ciani E, Lasagna E and D’Andrea M (2015). "Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds: a genome-wide intercontinental study". Genetics Selection Evolution. 47 (64): 9–10. doi:10.1186/s12711-015-0139-z. PMC 4536749. PMID 26272467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Pedrosa S, Arranz J-J, and Brito N (2007). "Mitochondrial diversity and the origin of Iberian sheep". Genetics Selection Evolution. 39 (1): 91–103 at pages 92, 100. doi:10.1186/1297-9686-39-1-91. PMC 2739436. PMID 17212950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Munro, J (2005). "Spanish Merino Wools and the Nouvelles Draperies: An Industrial Transformation in the Late Medieval Low Countries" (PDF). The Economic History Review. New Series. 58 (3): 437. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00310.x. S2CID 111690732.

- Rahn Phillips, C; Philips, W D Jnr. (1997). Spain's Golden Fleece: Wool Production and the Wool Trade from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 9780801855184.

- Sabatino Lopéz, C (1996). El origen de la oveja merina, Estudio 44. Ministerio de Agricultura y Pasca. p. 130.

- Munro, J (2005). "Spanish Merino Wools and the Nouvelles Draperies: An Industrial Transformation in the Late Medieval Low Countries" (PDF). The Economic History Review. New Series. 58 (3): 438–40, 455–9. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00310.x. S2CID 111690732.

- Munro, J (2005). "Spanish Merino Wools and the Nouvelles Draperies: An Industrial Transformation in the Late Medieval Low Countries" (PDF). The Economic History Review. New Series. 58 (3): 431–3, 437. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00310.x. S2CID 111690732.

- Munro, J (2005). "Spanish Merino Wools and the Nouvelles Draperies: An Industrial Transformation in the Late Medieval Low Countries" (PDF). The Economic History Review. New Series. 58 (3): 431–84 at page 436. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00310.x. S2CID 111690732.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 34–5.

- Munro, J (2005). "Spanish Merino Wools and the Nouvelles Draperies: An Industrial Transformation in the Late Medieval Low Countries" (PDF). The Economic History Review. New Series. 58 (3): 431–3, 437. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00310.x. S2CID 111690732.

- Klein, pp. 36-7

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 36–7.

- Rahn Phillips, C; Philips, W D Jnr. (1997). Spain's Golden Fleece: Wool Production and the Wool Trade from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780801855184.

- Reitzer, L (1960). "Some Observations on Castilian Commerce and Finance in the Sixteenth Century". The Journal of Modern History. 32 (3): 213–23 at pages217-8. doi:10.1086/238539. S2CID 153678227.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. p. 239.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 59–62.

- Klein, J (1920). The Mesta: A Study in Spanish Economic History 1273–1836. Harvard University Press. pp. 28–29.

- Ciani E, Lasagna E and D’Andrea M (2015). "Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds: a genome-wide intercontinental study". Genetics Selection Evolution. 47 (64): 3, 8. doi:10.1186/s12711-015-0139-z. PMC 4536749. PMID 26272467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Ciani E, Lasagna E and D’Andrea M (2015). "Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds: a genome-wide intercontinental study". Genetics Selection Evolution. 47 (64): 9. doi:10.1186/s12711-015-0139-z. PMC 4536749. PMID 26272467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Ciani E, Lasagna E and D’Andrea M (2015). "Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds: a genome-wide intercontinental study". Genetics Selection Evolution. 47 (64): 2. doi:10.1186/s12711-015-0139-z. PMC 4536749. PMID 26272467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Paterson, Mark (1990). National Merino Review. West Perth, Australia: Farmgate Press. pp. 12–17in 18600. ISSN 1033-5811.

- "Agriculture". Icenographic Encyclopedia of Science. Vol. 4. D. Appleton and Company. 1860. p. 731.

- Ross, C.V. (1989). Sheep production and Management. Engleworrd Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-13-808510-2.

- https://vermonthistory.org/william-jarvis-and-the-merino-sheep-craze Vermont Historical Society - William Jarvis's Merino Sheep]]

- McCosker, Malcolm, Heritage Merino, Owen Edwards Publications, West End, 1988 ISBN 0-9588612-3-4

- Lewis, Wendy, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ciani E, Lasagna E and D’Andrea M (2015). "Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds: a genome-wide intercontinental study". Genetics Selection Evolution. 47 (64): 10. doi:10.1186/s12711-015-0139-z. PMC 4536749. PMID 26272467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - The Edinburgh Gazetteer, volume 1, Archibald Constable and Co.: Edinburgh, 1822, p.570

- The Australian Merino, Charles Massey, Viking O'Neil, South Yarra, 1990, p.62

- ADB: Forlong, Eliza (1784 - 1859) Retrieved 2009-11-28

- Mary S. Ramsay, 'Forlong, Eliza (1784 - 1859)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press, 2005, pp 130-131.

- Taylor, Peter, Pastoral Properties of Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, London, Boston,1984

- "S.A. Merino Rams in Queensland". The South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1858 - 1889). Adelaide, SA: National Library of Australia. 19 June 1861. p. 2. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- J. Ann Hone, 'Peppin, George Hall (1800 - 1872)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, 1974, pp 430-431.

- Stock and Land Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-9-8

- The Land, Rural Press, North Richmond, NSW, 4 September 2008

- New England Merino Field Days Retrieved 2010-1-9

- The Australian Wool Fashion Awards Archived 2018-09-20 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-1-9

- "Abercrombie & Fitch Pledges Not to Use Australian Merino Wool Until Mulesing and Live Exports End". PETA.org. 2 October 2004. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- Animal Welfare (Care and Procedures) Regulations 2018

- The Macquarie Dictionary. North Ryde: Macquarie Library. 1991.

- "Breeds of Livestock - German Mutton Merino Sheep". Ansi.okstate.edu. 1998-12-10. Archived from the original on 2012-09-14. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- "Will a Sheep's Wool Grow Forever?", Modern Farmer, 24 July 2013

- Australian Wool Classing, Australian Wool Corporation, 1990, p. 26

Further reading

- Cottle, D.J. (1991). Australian Sheep and Wool Handbook. Melbourne, Australia: Inkata Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 0-909605-60-2.